15,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Parkstone International

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

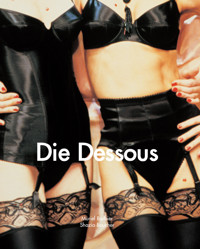

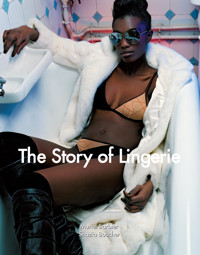

What is the social merit or purpose of all those bras and panties on perfectly sculpted bodies that we see spread across billboards and magazines? Many women indulge in lingerie to please men. Yet, ever since Antiquity, women have always kept lingerie hidden away under outer garments. Thus, lingerie must be more than erotic bait. Authors Muriel Barbier and Shazia Boucher have researched iconography to explore the relationship of lingerie to society, the economy and the corridors of intimacy. They correlate lingerie with emancipation, querying whether it asserts newfound freedoms or simply adjusts to conform to changing social values. The result is a rigorous scientific rationale spiced with a zest of humour. And the tinier lingerie gets, the more scholarly attention it deserves.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 254

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Text: Muriel Barbier and Shazia Boucher

© 2023 Parkstone Press USA, New York, December

© 2023 Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA, December

Image-Barwww.image-bar.com

© Chantal Thomass – Cover: photograph offered by Chantal Thomass

© Chantal Thomass/Photographs Frédérique Dumoulin – Ludwig Bonnet/JAVA Fashion Press Agency, illustration 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12

© Chantal Thomass/Photographs André Rau, illustration 1, 2

© Chantal Thomass/Photographs Bruno Juminer, www.valeriehenry.com, illustration 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18

© Chantal Thomass/Photographs Karen Collins, illustration 1, 2, 3

© Yaël Landman/Photographs Andréa Klarin, back cover, illustration 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8

© Axfords/Photographs Michael Hammonds, illustration 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8

© Musée de la Bonneterie, Troyes/Cliché Jean-Marie Protte, illustration 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

© V&A Images, The Victoria and Albert Museum, London, illustration 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

© Jean d’Alban, illustration 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8

© PMVP/Photographs by P. Pierrain, illustration 1, 2

© PMVP/Photographs by Ph. Ladet

© PMVP/Photograph by Briant

© PMVP/Photographs by J. Andréani, illustration 1, 2

© PMVP/Photographs by L. Degrâces, illustration 1, 2

© PMVP/Photograph by Giet

© PMVP/Photographs by Joffre, illustration 1, 2

© Photographs by Klaus H. Carl, illustration 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43

© Barbara/Photograph by Bernard Levy

© Ravage/Photograph by Didier Michalet

© Damart Serviposte

© Wonderbra, illustration 1, 2, 3

© Crazy Horse

© Wolford, illustration 1, 2, 3

© Princesse Tam-Tam, illustration 1, 2, 3, 4, 3, 4, 5

© Rigby and Peller, illustration 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8

© Musée des Arts décoratifs, Paris, Collection Maciet, illustration 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13

© Bibliothèque Forney, Ville de Paris, illustration 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13

© Chantelle, illustration 1, 2, 3, 4

© Brenot Estate/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ADAGP, Paris

ISBN: 978-1-78310-745-2

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world.

Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

Muriel Barbier - Shazia Boucher

Corset by Axfords.

Contents

Preface

Introduction

Underwear and fashion

Lingerie, corsetry and hosiery

How underwear began to allow the silhouette evolve

From Ancient Greece to modern woman: what have they been wearing under their clothes?

European women in the 15thcentury

Renaissance women

Women in“1900”

Materials

Colours

Underwear and Society

Stages of life

Rites of passage

Baptism

First Communion

From childhood to adolescence

Marriage

Mourning

The trousseau and its reflection in Society

Women’s work

The rise and fall of the trousseau

Caring for linen

Care of raw materials

A Woman’s private life and clothing

The nightdress

The negligee

The bedroom and private life

Underwear according to the season and social status

Clothing for children

Contradictory arguments about trousers for women and the corset

Trousers or bloomers

The corset

Sports underwear

Horseback riding

Cycling

Swimming

Dancers

Eroticism, seduction and fetishism

The eroticism of women’s underwear

Seductive and sexy underwear

Fetishism and women’s underwear: from private clubs to the catwalk

Economics

Lingerie manufacturing

How fashion was distributed

The current lingerie market

Distribution networks

Motivation to purchase

Communication

Advertising goes too far

Marketing

Some current directions for lingerie

The youth market

Underwear on top

Technological contributions to lingerie

Sportswear at the beginning of the 21stcentury

Sexy lingerie

A perfect marriage of lingerie and lace: an interview with Olivier Noyon, President of the Board of Noyon Dentelle

Conclusion

Glossary

1. Technical and general terms:

2. Terms specific to underwear:

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Index

Notes

Chantal Thomass, ensemble in white lace.

Autumn/Winter 2001-2002 Collection.

Preface

Lingerie is very directly and strongly linked to a women’s intimacy. For centuries, men have always believed that lingerie was created with the objective of seduction. There is no question that this aim exists. However, by choosing to put on pretty, seductive underwear, all women develop a slightly self-centred, even narcissistic, behaviour and attitude. In fact, lingerie contributes to a woman’s sense of ease with her body and, in this way, she accepts and loves her body better, becoming more confident and showing real assurance. The reason for this is very simple. Surprisingly, even though nobody can see her underwear, it really accentuates a woman’s figure and can sometimes shape her body to satisfaction.

Lingerie has too often been treated as an element of seduction. Men themselves created this phenomenon: a woman clad only in her underwear seems infinitely more sensual and sexual than a woman entirely in the nude. One could associate underwear with high heels. The latter have an effect on how a woman walks, making her more attractive, seductive and provocative. When combined with stockings, high heels have a certain charge, and an undeniable fetishist quality, as much for women as for men.

The perception and appreciation of the female form has undergone many radical changes. We could compare, for example, our early 21st century perception, to the 1960s and 1970s. In the sixties, when a woman got married, and even more so when she became a mother, her body was no longer meant to be seductive. Today this attitude is completely outdated and obsolete. In fact, women feel the need to be attractive at all ages, both before and after marriage, and even during their later years. This can be illustrated by the fact that, these days, a grandmother can be a beautiful woman and wish to dress to her best advantage in alluring underwear which enhances her figure. This revolution in customs concerning underwear is linked directly to innovation and technical considerations in the design of undergarments, and is subject to historical events. The history of lingerie deserves to be studied here. Lingerie, as opposed to the world of fashion, is a state of mind. A woman can love lingerie and wish to enhance her figure from the age of 15 to 75! Ready-to-wear fashion is a completely different universe from that of underwear. Clothes are always aimed at a distinct age group: fashion for a 15 year old girl is different from that of a woman of 30. Underwear, meanwhile, is much more a question of attitude and how a woman feels: a larger woman can be happy with her body, accepting herself as she is, and wish to enhance her figure with beautiful underwear. So lingerie should meet all aspirations and suit every kind of woman. As a designer, my work is focused in this direction. In order to design underwear which satisfies many types of woman, I like to observe those around me: my daughter, my assistants and women whom I encounter in the street. I can also be inspired by behaviour I have noticed in films.

Apart from my entourage, which plays an important role in suggesting new pieces to me, materials also inspire my designs. Textiles are essential. Since lingerie is closest to the female body and in intimate contact, the fabric and lace have to be soft, but this is not the only criterion. Today lingerie has to be comfortable and practical. In fact, although only 30 years ago French women (as opposed to Americans, for example) did not baulk at wearing and hand-washing very fragile undergarments, often lace-trimmed, sometimes needing ironing, today this would no longer be acceptable. Lingerie must be able to withstand machine -washing, be non-iron, and combine comfort (essential) and beauty in each piece. We cannot overlook the development of different textiles in the design and manufacture of underwear.

Going beyond materials, colour also plays an important part in lingerie. Black and white are always extremely flattering to the skin. Black (more particularly) can also diminish the defects that we all have. Warm colours (pink, red, raspberry) also help enhance the figure. On the other hand, lingerie in cool colours is harder to work with. Green and blue are beautiful, but are too often reminiscent of swimwear.

Lingerie should be associated with pleasure for a woman. The element of seduction remains, especially with certain undergarments: some of them are fascinating and inevitably inspire attraction. Stockings and suspenders make a woman extremely attractive, even bewitching. Bustiers, waspies and brassieres can be worn under a transparent shirt. The effect of this is bound to be equivocal, ambivalent and extremely fascinating when seen by others, and very flattering for the woman dressed this way.

I can distinguish two types of lingerie. On the one hand, the underwear that one wants to show off (particularly waspies, suspenders and stockings) and on the other hand, underwear just for the woman herself. This last category should be nice to look at but also comfortable. With regard to tights, for example, I particularly like to make attractive, lovely tights so that they can be worn everyday and so that they can maintain, in spite of what they are, an air of seduction when they are removed in the presence of one’s lover.

The essence and attitude of lingerie is all in suggestion. Three terms can be applied to lingerie today: elegance, seduction and comfort. These three ideas have to be combined when designing underwear, and any vulgarity has to be ruled out. To avoid this, underwear has to be humorous and fresh.

The world of lingerie affects everybody: women, who are wearing this underwear, as well as men, who believe women were wearing it merely to seduce them. The story of lingerie, as well as its history, deserves some attention.

Chantal Thomass

Chantal Thomass, long socks.

Autumn/Winter 2004.

Introduction

There are already a considerable number of works that have been written on women’s underwear. So why produce another one? The idea of this book is to share several facts: on the one hand, the attraction of underwear, the mystery which surrounds it and the fantasies it evokes, and on the other hand, the function of underwear and how it reveals the conditions of women, the development of its place in society and its status regarding men.

Even the term underwear itself brings to mind its function: being underneath, and therefore hidden. There can be numerous types: shaping underwear, revealing underwear, enticing, provocative, prudish or erotic underwear. Women’s underwear is erotic without a doubt. From Grecian times to the most modern micro fibre bras, women’s underwear has been sensually charged, as much for the woman wearing it as for the man (or woman) who removes it. What is the reason for this amazing power of seduction? The fact that underwear is hidden? And rarely revealed? Perhaps because it is in intimate touch with a woman’s body? However, eroticism is not the only matter of interest in women’s underwear.

During the development of western clothing, lingerie and corsetry have had a fundamental role. It allows one to structure one’s shape, modify the figure and change following the flights of fashion. Underwear itself follows constantly changes with the latest fashion. It is designed using shapes, materials and colours which correspond to the tastes of the time: even if we can say that women’s underwear is created in the image of fashion, it is not actually that simple, and shapes, types of undergarments, and the choice of materials and colours very often have a social context.

A woman wears underwear that varies according to her circumstances. From the beginning to the end of her life a woman experiences physical change and changes in her social status, and her underwear reflects this.

It becomes emblematic of the times and of each woman’s role in her society and class. In addition to this, throughout life, daily activities require different underwear, such as for sport, a day’s work or the evening. The most tantalising underwear is, of course, for love.

Sophisticated underwear with the purpose of seduction had, and continues to have, a symbolic role in western Judeo-Christian society. Whether idolised or demonised, women’s underwear symbolises taboos and sexual prohibitions lead to numerous fantasies, erotic ideas and even to fetishism.

Underlying the existence of these fashion objects and erotic dreams is the world of business and industry, whose origins go back in history to linen maids, corset makers and hosiers. The sale and distribution of women’s underwear is a well-organised and rapidly expanding machine, dealing with such diverse retailers as chic lingerie outlets, mail-order catalogues and sex shops, where every woman can find what she desires. Advertising is aimed at attracting both men and women with lace, satin and embroidery modelled on voluptuous models.

The world of women’s underwear, whether hidden or on display, is a rich one. Underwear was originally designed for hygienic reasons and to enhance intimate parts of a woman’s body, but it is now aimed at much more than provoking desire. In particular, during its development over the years, it has shown the progressive liberation of the female body as well as her position in patriarchal western society.

So let us enter this lace-trimmed history whose aim is to inform and titillate the reader. Our studies were based on bibliographical research, but the work does not refer to scientists or experts. The aim of the book is to please and charm the reader.

Yaël Landman, ensemble.

Autumn/Winter 2003.

Underwear and fashion

Iron pair of stays, first half of the 17th century.

Leloir Fund, Musée Galliera, Paris. Inv. 2002.2.X.

Nicolas-André Monsiau, The Lace, 1796.

Engraving, vignette for the works of Rousseau.21x14cm.

Maciet Collection, Bibliothèque des Arts décoratifs, Paris.

Lingerie, corsetry and hosiery

Underwear is varied and prolific, whether it is hidden or displayed, discreet or provocative. There are three usual ways to classify this multitude of garments: lingerie, corsetry and hosiery.

Lingerie’s main role is that of hygiene. It is positioned between the body and clothes, and it protects the body from outerwear made of less comfortable textiles while it protects the clothes from bodily secretions. Because of this, it is generally made from healthy materials which have varied according to the times. In this way lingerie is really about feminine intimacy and hygiene. In fact, the first linen that was in contact with the female body was used for menstrual flow and is the precursor of our sanitary towels.[1]

The term body linen is also used for lingerie. We use this term to talk about certain undergarments such as petticoats, chemises, bloomers, long johns, briefs, vests and slips.

In families of modest means, or in wartime, certain undergarments have been made from worn out household linen, often old sheets. Materials used for body linen are similar to those used for household linen. Comfort is the first thing they have in common, with cotton being the most popular, as it is soft, light and hygienic. Other materials of all types of luxury are used to make lingerie: linen, silk, relatively light synthetic weaving, such as cloth, satin, jersey, lawn, muslin, percale or net. Sometimes these fabrics are embellished with ornamentation and, very often, with provocative decoration. Because lingerie is not limited to a protective role, it is also an elegant part of clothing. We often see lingerie “coming out on top” as it is revealed or is completely displayed for reasons of seduction, fashion or provocation. It also presents frivolous ornamentations such as lace, embroidery and ribbons. Depending on who is wearing it, colours can vary according to the age, social position, taste, or the effect required by fashion of the wearer. But it is rarely completely revealed as it is associated with nudity, as can be seen in Georges Feydeau’s play Mais n’te promène donc pas toute nue!(“You are surely not going out completely naked!”) where Ventroux takes his wife Clarisse to task when their son sees her in her chemise. “We can see through that like tracing paper!” he says but she, in turn replies that wearing one’s daytime chemise is not like being naked.[2] This episode shows that a woman feels that lingerie covers her while for a man it draws attention to the nudity beneath.

Because of its contact with the skin and its closeness to the female form, lingerie has always been the object of male fantasy, a fact which is judiciously played upon by woman and their lingerie. Catching a glimpse of petticoat frill in the 18th century, as in the 19th century, had an impact on the observer’s imagination in the same way that detecting panties or a G-string under a girl’s jeans would have today. Lingerie has an erotic charge because it is the closest clothing to the private female form.

Corsetry also plays a part in the world of seduction. This garment is to clothing what a framework is to a building. But this framework is applied to an existing foundation; the female body. The role of corsetry is to shape the body and to impose a fashionable silhouette upon it.

Body with whalebone, 18th century.

Fabric decorated with flowers.

Leloir Fund, Musée Galliera,

Paris. Inv. 1920.1.1856.

Corset. Pink silk, backed with linen, stiffened with whalebone and trimmed with pink silk ribbons.

England, c. 1660-70, Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Box “The Mexican Corset”, 1869.

Musée de la Bonneterie, Troyes.

Box “The Mexican Corset”, 1869.

Musée de la Bonneterie, Troyes.

Corset in red satin, yellow leather and whalebone, with a steel hour-glass form, 1883.

Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Black and white silk slip, muslin stockings with silk and lace. Commercial catalogue,

Grands Magasinsdu Louvre, Paris, Summer 1907.

Pieces of corsetry were used to transform the three main parts of the body: the waist, bust and hips. The new silhouette was constructed around these three points. In Les Dessous à travers les âges (“Underwear throughout the ages”), Armand Silvestre describes a ”good corset” in the following terms: “the top must be sufficiently widely cut to support the breasts without crushing them, the armholes should be well-formed; the lining of the fabric should be fine, well-inserted and flexible […] finally, it should follow the lower body and finish on the hips at a firm point of arrival and follow the natural direction of the woman’s side”[3]. Corsetry enhanced the body’s curves and moulded it into new lines. It made the bust round, uplifted, curvaceous or flattened; the waist could be larger or smaller, non-existent or well-defined; hips could seem slimmer or wider. Corsetry dictated the shapes of fashion and often worked against nature. While lingerie revealed a woman’s private world, corsetry was made to create illusion. Corsetry was what made the woman wearing a certain dress fashionable.

The term ‘corsetry’ includes undergarments such as stays, corsets, girdles, waspies, bustiers, farthingales, panniers and crinolines*.

Corsetry was made of internal bones which compress and control the body. These bones were made from sturdy materials such as whalebone, cane, horsehair, steel and elastic fibres. Originally this underwear was meant to be worn over clothes, then over lingerie, so it would be less obvious that it was made out of more sophisticated fabrics than those used for lingerie. Sometimes pieces of corsetry were matched to the clothing or to certain types of lingerie, such as a petticoat.

In this way one can see that corsetry was more fashionable and followed trends because it is visible (in the Middle Ages particularly, corsetry was worn over the dress) and especially because it moulds the figure.

Because of this, corsetry has been criticised to a much greater extent than lingerie. The supporters of corsetry saw in it a symbol of female morality – a woman’s body being maintained and reflecting her upright behaviour. Doctors, hygienists, and later, feminists, have accused designers and manufacturers of wanting to confine the female body inside a structure which is far from natural and that can damage the body. In spite of this criticism, women have accepted and put up with boning since, for them, it was simply a question of fashion: it was a way of disguising figure faults. The female body has long been considered weak, and extra support was considered necessary. 1932 Vogue testified: “Women’s abdominal muscles are notoriously weak and even hard exercise doesn’t keep your figure from spreading if you don’t give it some support”[4].

In fact, corsetry is a woman’s major ally (if she can bear a little suffering) as it allows her to hide any bad points and accentuate her good points! This is the case of Caroline, Honoré de Balzac’s Petites Misères de la vie conjugales (“The Small Miseries of Married Life”), who wears her “most deceptive corset”[5]. Finally, like all lingerie, corsetry carried a significant erotic charge, as it accentuates the most emblematic aspects of the female body.

We would not have covered everything if we failed to mention hosiery here. This third family consists of the manufacture, industry and sale of clothing of knitted fabrics including stockings, socks and certain items of lingerie such as briefs or vests. Hosiery is characterised by the weaving technique which is employed when using materials such as wool, cotton, silk, nylon and today, micro fibre.

Hosiery completes the lingerie-corsetry family and has benefited from great technical advances as a result of improvements in trade and the industrialisation of the sector.

Today, the distinction between lingerie, corsetry and hosiery is rarely made as there is often an overlap between the various different domains (underwired bras, support tights, support briefs). The underwear which we wear today is the result of the development of these three families. Their hygienic, supportive and aesthetic qualities interlink in 21st century underwear.

Combinations. White cotton with Bedfordshire Maltese lace trimming, red sateen corset and steel wire bustle. England, c. 1883-1895,

Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Underwear. Cotton chemise, whalebone corset of blue silk; crinoline spring steel hoop-frame covered with horsehair, with a braided horsehair frill. England and France,

c. 1860-1869,Victoria andAlbert Museum, London.

Corset by Axfords.

Albert Wyndham, The Corset, c. 1925.

Silver print, 23.6x17.5cm. Private collection.

François Gérard, Portrait of Juliette Récamier, 1805.

Oil on canvas, 225x148cm.Musée Carnavalet, Paris.

How underwear began to allow the silhouette evolve

Each era develops its own aesthetic idea that replaces the previous one. Underwear plays a fundamental role in creating a fashionable silhouette. Changing shape is based on integral points in clothing: shoulders, waist, bust and hips.

In ancient times, a draped form covered the body and outlined one’s figure. This was the case in Egypt where underwear did not exist and the body was naked under the tunic. Slaves, dancers and musicians were entirely naked, which marked the difference in status between themselves and their masters who wore translucent tunics. Even though an open tradition existed in classical and Hellenistic Greece concerning clothing and draping, the female form was disguised with straps that flattened the bust and hips. The figure was ruled by androgyny[6]. Hellenistic women appeared completely draped and their femininity disappeared under the panels of their robes. Roman civilisation also fought against curves. In an exclusively male world where women had no role, they were forbidden from showing any specific body characteristics. Certain doctors even proposed treatment to prevent the bust developing too much: Dioscoride[7] advised applying powdered Naxos stone to the breasts; Pline[8] suggested scissor-grinder’s mud, and Ovid[9] recommended a poultice of white bread soaked in milk. There is no evidence that these magic potions were effective, but their existence does show a certain disdain for curves and soft shapes as well as a desire to disguise the female form.

In the Middle Ages the figure was slim although the waist was beginning to be defined. During the 14th and 15th centuries it was important to be slender. This was helped by adjusted underwear and, in particular, a surcoat which flattened the breasts, accentuated the curve of the hip and showed off the belly. The end of the Middle Ages was marked by the great Plague epidemics and a round belly and visible belly button were appreciated as a mark of fertility and a sign of promise for a depopulated Europe. The English poet John Gower (1325-1403) mentions this taste for women with a prominent belly in these terms: “Hee seeth hir shape forthwith all / Hir body round, hir middle small.[10]“

The strict confinement obtained with interior boning which compresses and rules the body is in opposition to these supple clothes of olden times is.

European 16th century clothing is marked by a certain uprightness influenced by Spain. The farthingale was a garment which was designed to make skirts more voluminous. It was adopted in England in 1550 and it became all the rage in 1590. In Spain, it did not disappear until 1625. The farthingale gave volume to the hips, accentuated the belly and demarcated the curve of the body. Underneath, women wore bloomers which were sometimes “deceptive” (padded) that shaped thighs and buttocks and increased the volume of skirts. The bust was shaped like a funnel, held rigidly by the basque which compressed the waist and opened up towards the shoulders.

In the 17th century, the female bust regained its round shape and was accentuated by stays up to the top of the torso tightly laced to the waist. Around 1670, the bust lengthened as the stays reached further up the front and the back of the waist. In the 18th century stays were worn very early by young girls and they reached even higher up the back. At the end of the 18th century certain women cheated by reverting to false breasts hidden in their stays.

Felipe de Llano, Infante Isabelle Claire Eugénie, 1584.

Oil on canvas, Museo del Prado, Madrid.

The Flagellation of the Initiated and the Dancer,

2nd-beginning of the 1stcentury BC.

Fresco, Villa of Mysteries, Pompeii.

Picture from the Royal Throne of Tutankhamen representing the young pharaoh and his wife in a translucent tunic, 18th dynasty, 1350-1340 BC.

Wood, gold, coloured glass, semi-precious stones.

Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

The 18th century saw a definitive end to the farthingale when the fashion for flowing dresses arrived. Panniers shaped the skirts, following rapidly evolving trends. The panniers of 1718 were quite rounded, and became oval around 1725, remaining this way until 1730. Later, they took on a multitude of forms including the elbow pannier which stretched out a long way to the sides. After 1740, each side of the skirt had a pair of small panniers which gave it a flattened shape from the front and back but a very wide aspect from the front. At the end of the 18th century, panniers were replaced by the bustle worn behind and which improved or enhanced existing curves. From 1770 onwards, there was some contemporary criticism of stays, including from Jean-Jacques Rousseau who advocated a return to simplicity and nature. Other critics, such as Bonnaud in the 1770s La Dégradation de l’espèce humaine par l’usage du corps à baleine(“The Degradation of the Human Race by the Use of Stays”), launched real medical and educational “crusades”. Nothing could be done: a small waist, large skirt and generous bust remained the flavour of the day. Nevertheless, fashion evolved towards a return of the slim figure, and the pannier gave way to the bustle which, in turn, gradually disappeared. The result of this revolution was a new slender fashion. It started in France, introduced by the “Merveilleuses” (“The Marvels”) like Mme Récamier and Mme Tallien. This long, straight silhouette conquered England following the emigration of Rose Bertin after the French Revolution. With the return of the Greek tunic, the first fashion revival in history was recorded. The silhouette was long and straight with a high bust. But this did not mean that underwear disappeared for those who were not built like fashion plates. In 1800 the corset was still necessary to disguise too ample curves: the best-known corset makers were Lacroix and Furet. During the first Empire, the fashion for widely spaced breasts was launched by Louis Hippolyte Leroy and made corset-wearing indispensable. The “Ninon” was padded to give opulence to the body and reached to the waist.

Woman’s underwear. Fine linen shift; red silk corset with damask and side hoops, pink striped linen.

England, Mid 18th century, c. 1770-1780 and 1778,

Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Swing, 1766.

Oil on canvas, 81x65cm. Wallace Collection, London.

Distribution of panniers from around