Arthur E. P. Brome Weigall

The Treasury of Ancient Egypt

UUID: 8127d540-cf3f-11e5-83aa-0f7870795abd

This ebook was created with StreetLib Write (http://write.streetlib.com)by Simplicissimus Book Farm

Table of contents

PART I

CHAPTER I.

CHAPTER II.

CHAPTER III.

PART II.

CHAPTER IV.

CHAPTER V.

CHAPTER VI.

PART III.

CHAPTER VII.

CHAPTER VIII.

CHAPTER IX.

PART IV.

CHAPTER X.

CHAPTER XI.

CHAPTER XII.

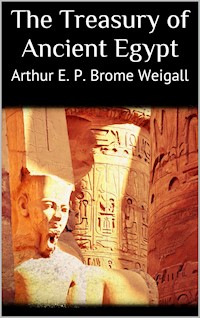

A statue

of the hawk-god Horus in front of the temple of Edfu.The

author stands beside it.

PART I

THE

VALUE OF THE TREASURY."History

no longer shall be a dull book. It shall walk incarnate in every just

and wise man. You shall not tell me by languages and titles a

catalogue of the volumes you have read. You shall make me feel what

periods you have lived. A man shall be the Temple of Fame. He shall

walk, as the poets have described that goddess, in a robe painted all

over with wonderful events and experiences.... He shall be the priest

of Pan, and bring with him into humble cottages the blessing of the

morning stars, and all the recorded benefits of heaven and earth."Emerson.

CHAPTER I.

THE

VALUE OF ARCHÆOLOGY.The

archæologist whose business it is to bring to light by pick and

spade the relics of bygone ages, is often accused of devoting his

energies to work which is of no material profit to mankind at the

present day. Archæology is an unapplied science, and, apart from its

connection with what is called culture, the critic is inclined to

judge it as a pleasant and worthless amusement. There is nothing, the

critic tells us, of pertinent value to be learned from the Past which

will be of use to the ordinary person of the present time; and,

though the archæologist can offer acceptable information to the

painter, to the theologian, to the philologist, and indeed to most of

the followers of the arts and sciences, he has nothing to give to the

ordinary layman.In

some directions the imputation is unanswerable; and when the

interests of modern times clash with those of the past, as, for

example, in Egypt where a beneficial reservoir has destroyed the

remains of early days, there can be no question that the recording of

the threatened information and the minimising of the destruction, is

all that the value of the archæologist's work entitles him to ask

for. The critic, however, usually overlooks some of the chief reasons

that archæology can give for even this much consideration, reasons

which constitute its modern usefulness; and I therefore propose to

point out to him three or four of the many claims which it may make

upon the attention of the layman.In

the first place it is necessary to define the meaning of the term

"Archæology." Archæology is the study of the facts of

ancient history and ancient lore. The word is applied to the study of

all ancient documents and objects which may be classed as

antiquities; and the archæologist is understood to be the man who

deals with a period for which the evidence has to be excavated or

otherwise discovered. The age at which an object becomes an

antiquity, however, is quite undefined, though practically it may be

reckoned at a hundred years; and ancient history is, after all, the

tale of any period which is not modern. Thus an archæologist does

not necessarily deal solely with the remote ages.Every

chronicler of the events of the less recent times who goes to the

original documents for his facts, as true historians must do during

at least a part of their studies, is an archæologist; and,

conversely, every archæologist who in the course of his work states

a series of historical facts, becomes an historian. Archæology and

history are inseparable; and nothing is more detrimental to a noble

science than the attitude of certain so-called archæologists who

devote their entire time to the study of a sequence of objects

without proper consideration for the history which those objects

reveal. Antiquities are the relics of human mental energy; and they

can no more be classified without reference to the minds which

produced them than geological specimens can be discussed without

regard to the earth. There is only one thing worse than the attitude

of the archæologist who does not study the story of the periods with

which he is dealing, or construct, if only in his thoughts, living

history out of the objects discovered by him; and that is the

attitude of the historian who has not familiarised himself with the

actual relics left by the people of whom he writes, or has not, when

possible, visited their lands. There are many "archæologists"

who do not care a snap of the fingers for history, surprising as this

may appear; and there are many historians who take no interest in

manners and customs. The influence of either is pernicious.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!