Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

An entertaining and enchanting collection of myths, tales and traditions surrounding the seas, skies and woodlands that make up our natural world. Enter an enchanting world where the mysteries of the seas, skies and woodlands come alive through shared myths, legends and folk tales. From the majestic creatures that dance beneath the waves to the celestial beings that populate the heavens and the spirits that reside within the forests, The Treasury of Folklore offers a portal into the lore of the natural world that has been whispered through the generations. In this mesmerising compendium you'll embark on a journey through the rich tapestry of myths, legends, and tales that have been woven into the very fabric of our natural world. You'll tread mysterious waters and be beguiled by the sirens and sea monsters, soar to new heights with winged Pegasus and uncover stories of celestial beings, from thunder gods to constellations that have guided traveller's across the heavens. And as you wander through the ancient woods, you'll encounter spirits between the branches, insatiable cannibalistic children hewn from logs and the promise of the big, bad wolf. The stories included here traverse countries and continents and have been carefully selected to highlight how humans are linked through time and place, with shared dreams, fears and ways of rationalising the unknown. Immerse yourself in the tapestry of tales collected in these pages, each story a testament to the enduring enchantment of the seas, skies, and woodlands.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 451

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Authors’ Note

Introduction

Waterlands

Seas and Rivers: Wonderous Waterlands

The Lure of Ocean Waves

Famous Floods

Mermaids, Selkies and Spirits of the Deep

Monsters from the Deep

Islands of Fable and Myth

Claimed by the Waves: Underwater Worlds

Scheherazade’s Tales: One Thousand and One Nights

Red Sky at Night: Sailor Superstitions from Across the Glove

The Graveyard of the Atlantic: The Mystery of the Bermuda Triangle

Sacred Rivers & Mysterious Lakes

Sacred Rivers

Rivers of the Underworld

Waterfall Folklore

The Top Five River Spirits from Around the World

The Mysterious Waters of Scotland

Water Horses: Majestic and Malevolent Creatures from the Depths

Humped Serpents and Vicious Eels: Loch Ness and the World’s Most Fearsome Lake Monsters

The Folklore of Swamps and Marshes

Be Careful Where You Rest: The Insatiable Appetite of the Irish Joint Eater

Well Folklore

The Fountain of Youth

Myth and Mystery: The Lady of the Lake

Wooded Worlds

Woodlands and Forests: Wooded Worlds

Into the Trees

The World Tree

Trees of Myth and Mystery from Around the World

The Marvellous Mushrooms of the Forest Floor

The Trees of Christmas

Woodland Creatures

Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?

Bears, Gods and Heroes

Virgins, Huntsmen and Jesus Christ: The Quest for the Unicorn

Jackalopes and Wolpertingers: Creating a Legend

What Lurks in the Lumberwoods: The Most Fearsome of Critters

Folk of the Forests

A Giant Among Lumberjacks: Paul Bunyan and the North American Lumber Camps

Lords of the Wild

At One with the Trees: Tree Nymphs and Spirits

Forest Hags from Around the World

Fearlessness in the Forests

Starry Skies

Stars and Skies: A Journey through the Skies

Stars and Heavens

Solar Deities: Gods and Goddesses of the Sun

A Fateful Flight: Daedalus and Icarus

Sun-Got-Bit-By-Bear: Eclipses of the Sun

Hina: The Woman in the Moon

Man, Rabbit, or Jack and Jill? The Many Faces of the Moon

The Morning Star and the Evening Star: A Romanian Tale

The Seven Sisters: Orion and the Pleiades

How the Milky Way Came to Be

Soaring Souls and Shooting Stars: Star Superstitions from Around the World

Sumptuous Skies

Stallions of the Skies: Pegasus and Other Soaring Steeds

Birds of Myth and Legend

The Firebird

Come Rain or Shine: Weather Lore and Superstitions

Somewhere Over the Rainbow: Rainbows in Myth and Legend

Shimmering Lights and Walrus Heads: The Folklore and Legends of the Auroras

Flying Cryptids

Conclusion

Acknowledgements

Index

AUTHORS’ NOTE

In this collection of customs and stories, we have tried to build bridges between people from all places. We wanted to show how people tell similar tales wherever they are from. In order to do this, we have unearthed stories from across the globe and gathered them together here. Many of the stories in this book were chosen to highlight this issue of cultural appropriation, and we have tried to explain how such stories have been appropriated, and the damage that this does.

With this in mind, we have tried to use sources from the culture in which each tale or tradition originates, preserving the essence of the tale in language that would be familiar to those who share its heritage. And while it is sometimes more difficult for the reader, we have used the names people call themselves, and the words that these people would choose to tell this tale, since these are important things. It is a mark of respect and acknowledgement that these stories belong somewhere, and belong to the people of that place. For traditions and stories from living traditions, we have made sure to use the present tense, and not erroneously mark these as a thing that is past. Folklore refers just as much to the living, breathing folk groups and customs we see all around us today.

We have purposefully chosen folklore that uncovers the similarities between our different cultures. Yet we have preserved the details of each tale, hoping to display the intricacies that make each folk group so mesmerizingly different, to evoke the places where this folklore originates, and to celebrate their individuality.

We would like to thank everyone who has shared their tales and traditions with us, and we hope we have done justice to the wonderful folklore that unites us all.

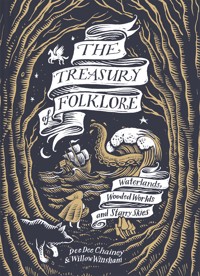

INTRODUCTION

When we first envisaged the Treasury of Folklore book series, we imagined it as one book covering all types of physical landscapes where humans live across the world. The material we uncovered, however, greatly surpassed what could be contained within a single book. Yet now, we finally have the opportunity to compile much of this folklore in one special volume: a compilation of our favourite folklore contained within the three original books in the series.

We started the series in search of understanding. We aimed to explore how humans across the globe create customs, beliefs and tales around the places they live in. Although the details of these beliefs and customs vary from place to place, the truth that we unearthed is that, in so many ways, we are all inherently the same. We discovered that we, as humans, all share primal fears and dreams, no matter where we live, how we dress, or what we choose to name the monsters of our myths and legends. Gazing across the ocean into the vast horizon, we all long for the treasures and pleasures that the wide world around us can offer. We all dread the unknown as we gather around our campfires in the darkness of the nighttime forest. We all stand in awe of the eternity of time under the glimmer of ancient stars, wondering about the unwritten future of our own short lives.

Here you will not find a collection of stories, but a pathway leading into the world of folklore in all its forms: a breadcrumb trail of tales, traditions and beliefs from around the world. We have gathered these together around the timeless human themes they speak to. You will find folk magic with hope and fear at its core; customs that ease the pain of loss, and traditions performed from grief and an eternal longing for the impossible. You will hear tales of temptation and jealousy; myths and legends of our innate fear of divine retribution and death. We explore the hidden meanings that simmer below the surface of our folklore – the wisdom of communities across the world passed down through the ages, and the lessons they convey for each new generation that follows.

While including folklore of all kinds, from all places, across all times is an impossible feat, we hope this small collection will help you to delve more deeply into the subject. We invite you to use this understanding to pick up the trail of the tales and traditions of the places familiar to you. By forging the path of your own folklore journey, you will uncover the hidden depths and meaning beneath the stories and customs of your own communities, and gain a deep understanding of how folklore shapes your life, relationships and the world around you.

Join us as we dive deep into the heart of these stories, beliefs and traditions, and uncover the shared humanity that binds us all.

WATERLANDS

SEAS AND RIVERSWonderous Waterlands

From the earliest times, the sea has been a major part of life for many people around the globe. Humans walked across continents, and traversed the seas, to settle the shores of distant lands that belonged only to the beasts of the earth. Since the ice receded, and tundra spread over our planet, island and coastal communities sprang up and their lives and livelihoods relied on the sea, as they still do today. From folklore, myths and legends we can see that people have always viewed the sea as majestic, with a power to consume all. It is a regenerative, creative force that churns outside the bounds of time, roaring its way through land, animals and humans alike. In the face of this, people look at the sea with an all-consuming awe, and see the gods and goddesses of creation shimmering in its depths.

For thousands of years, great heroes and heroines from across the globe have traversed the seven seas, battling pirates and monsters for the prize of treasure, fame and the promise of a life of adventure and the lure of unknown shores. On their voyages, archetypal heroes are often favoured by gods of the sea and are witness to miraculous beasts, underwater worlds and palaces, and to fabled islands. Whether these heroes on great voyages seek fame, fortune or pirate treasure, it’s certain that the lure of the ocean and its secrets are as old as time itself.

A resounding theme in ocean folklore is the unknown, and the innate human fear of what one cannot see lurking under the waves in far-flung seas. Many stories tell of ghostly bells, still ringing from the depths of sunken towns that were swallowed by the sea – as if the inhabitants still go about their daily tasks, submerged under the dark waters among the waving seaweed fronds. For many on the biting shores of the Northern Hemisphere, the sea is a place of raging storms, ghostly mists and strange noises that pierce the frosty beaches on dark nights and conceal hidden threats to life and land. For those in the southern seas, there are endless tales of sea monsters and temptresses in the clear waters and sweet lagoons, who lure men to their doom.

When we look at sea folklore from around the world, we find it is often used to explain the unexplainable: unquenchable feelings of lust, illegitimacy, disappearance, bad luck, death, starvation or a fruitless yield. Folklore indeed teaches us that the sea is dark, illicit and full of temptations. The ocean can offer the things of our wildest dreams – treasure, love, a different life – but to get these we must face our darkest nightmares: the terrifying things that lurk beneath the surface in our subconscious minds. When we face these, and defeat them, we win the treasures of the deep and see sights most can only dream of; yet one thing that folklore teaches – make no mistake – is that the treasures of the sea always come with a price.

Similarly, rivers hold a great deal of symbolic meaning across the globe. Rivers are boundaries and barriers, yet we can transgress these with the help of the gods and their rituals. In myth and legend they help us travel between worlds or spiritual realms. The rivers of the Underworld accompany the dead on their journey through Hades in Greek myth, and in Scandinavian lore one must wade through rivers on a journey to the land of the dead. In traditional Sámi tales of Finland and Sweden, double-bottomed sáiva lakes act as doorways to their Underworld, with shamans able to speak to the spirits of the lakes, who could help protect people and ensure a plentiful fishing haul if offerings were left for them.

Rivers and lakes are the things of the sea, but tamed; they have similar dangers, but their dangers are tempered and we humans are offered a choice, a forked path, through which to choose our fate. If we fail, we will metaphorically be lost in our own human frailty, and the gifts and wisdom of the otherworld and its gods are taken from us. Such gifts offer opportunities to transcend our lower selves, and raise us up to be godly, with super-human powers and skills. They show us the amazing things that are on offer to us, and there for the taking – if only we do things in the correct way and choose to act with wisdom and kindness.

FAMOUS FLOODS

Some of the most famous flood stories are those of Noah, who makes an appearance in the Christian Bible, Jewish Torah and Islamic Quran. Yet did you know that a devastating flood that almost extinguished humankind is a motif that resounds through myths from all corners of the ancient world? Many nations share a story of a great deluge, and while there are multiple versions of the myth, we see common threads running through them all. Many flood myths appear to be tales of the gods’ punishment for the errant ways of humans, or for over-population, while others tell of the repopulation of the earth or human origins. One item that appears almost consistently is a boat or vessel that saves a few chosen people as a reward for their piety or wisdom, often filled with all the plants and animals needed to rejuvenate life across the earth. The stories commonly tell of a brother and sister pair, yet some have bewitching details all of their very own, unique to the land where they originate.

We find the roots of Noah’s deluge in earlier stories, like that of the ancient Near Eastern Epic of Gilgamesh, which was passed down from the Sumerians to the Assyrians and Babylonians. It describes Utnapishtim as a great ancestor who survived a terrible flood and was granted immortality. Utnapishtim was instructed by the god Enki to build a giant boat; everything that was not within the ship would be destroyed by a great flood. Afterwards, Utnapishtim sent out three birds: a dove, a sparrow and a raven. Only the raven did not return – a sign that the flood was over. As a reward for his faith, the gods gave him and his wife the gift of immortality.

Many of the Noah stories follow this pattern, yet some have quirky details unique to their country of origin. Noah appears in traditional Indigenous tales of the Dreamtime flood, woramba, from the Fitzroy River area of Western Australia, where it’s said that the Ark Gumana carried Noah, along with Indigenous Australians, finally settling on the flood plain of Djilinbadu. It’s believed that the idea of the ark ultimately landing in the Middle East was a lie, to keep Indigenous Australians in subservience. However, another Australian story gives a different explanation for the flood. The medicine man Grumuduk, who could call the rains and cause plants to grow and animals to be fruitful, was kidnapped by a plains tribe. On his escape he vowed that whenever he walked on an enemy’s territory, salt water would follow in his path.

Strangely, mice often find themselves in starring roles in the flood myth genre. A Russian folk tale recounts how the Devil told Noah’s wife to prepare a strong drink in order to discover Noah’s reason for building the ark, which indeed she did, finding out the secret that God had entrusted to him. She was also responsible for the Devil, who had transformed himself into a mouse, secreting himself away on the ark and gnawing holes into the bottom.

An Indigenous flood story from northern Siberia also mentions mice. Here, seven people survived the flood on a boat, yet a horrendous drought followed it. They dug a hole, which filled with water, yet all but one man and one woman died from starvation; these two had eaten mice to save themselves. The whole of humankind are descendants of this pair.

The boat is a recurring symbol in many stories. In Hindu tradition, a demon stole the sacred books from Bramha; humanity, in its entirety, became corrupt, apart from the seven Nishis and Satyavrata, the prince of the maritime region. One day, when Satyavrata was bathing, the god Vishnu came to him in the form of a fish, warning him of the great deluge that would come to destroy all that was corrupt on the earth. He told Satyavrata that he would be secured in a capacious vessel, and instructed him to take with him the seven holy men, and fill it with all the plants and animals of the land. With this, Vishnu disappeared, and over the next seven days Satyavrata did as he was commanded and prepared for the waters. Indeed, within a week the rains began. The rivers broke their banks and the oceans flooded the land, bringing a large ship floating towards them. Satyavrata bundled the holy men on board, along with their families, and all the herbs and grains he had been instructed to bring, along with two of each animal. The great Vishnu came again to protect the vessel, by transforming into a giant fish and tying the boat tightly to himself to survive the flood. When the waters subsided, Vishnu killed the demon that had stolen the holy books, and taught their lessons to Satyavrata.

In the flood myth from Cameroon, the prophetic animal is a goat, rather than a fish. The tale tells that a woman was grinding flour one day and allowed a goat to lick it up. In gratitude, the goat warned her to take up her possessions and flee before the flood ensued.

Some flood stories take an even more fantastical turn. For the Soyots of the Republic of Buryatia in Russia the world is carried on the back of a giant frog or turtle. While this idea might be familiar to many, it might surprise you to know that it’s told that the creature moved just once and from this tiny act the cosmic ocean flooded the earth; in fact, the creation stories of Eastern Siberia say that if the world frog moves even a little, the world will shake violently, and earthquakes can rain down on humanity.

We also find that many myths link a worldwide flood with giants. Berossus, a Chaldean writer, astronomer and priest of Bel in Babylon in the 3rd century, adds to the Noah story by describing the antediluvians that were left after the flood as a depraved race of giants; all except ‘Noa’ that is. Instead, Noa revered the gods, and resided in Syria with his three sons: Sem, Jepet and Chem. He foresaw the oncoming destruction in the stars and had set about building a ship to save his family. Remnants of the boat are still said to exist where it settled, on the peak of Gendyae or Mountain, and bitumen was still taken from it to ward off evil well into the 19th century. Similar tales of an antediluvian race of giants exist in Scandinavian flood traditions, where Odin, Vili and Ve defeated the primordial giant Ymir. All but two of the giants, Bergelmir and his wife, were killed in a great flood that arose from the blood of Ymir’s gushing wounds. All giants are descended from these two.

Stranger still, elves appear in a Chingpaw flood story from the northern region of Myanmar. In this tale, brother and sister Pawpaw Nan-chaung and Chang-hko fled to safety on a boat, taking nine cocks and nine needles with them. Once the rain had ceased, they threw one of each from the boat, until they came to the last pair. On throwing these overboard, they finally heard the cock crow and the sound of the needle hitting the bottom. With this they were able to return to dry land, and soon came upon a cave in which two elves had made their home. The siblings stayed with the elves in their cave, and all was well with them; that is until Chang-hko gave birth, and left the infant in the care of the elfin woman while she went out to work. This is where the story takes a gruesome turn: the woman was a witch! Faced with the incessant wailing of the child, the witch took it to a crossroads where nine roads met, chopped it to pieces and scattered the body about, yet keeping a little with her, with nefarious intent. On her return to the cave, the elf-witch made a curry from the remaining parts of the babe, feeding it to the unsuspecting mother. When she discovered the truth, in her utter dismay, Chang-hko fled to the crossroads to plead with the Great Spirit to avenge her child and bring it back to life. The Great Spirit deemed this impossible, but instead promised to transform the remaining pieces of her child into the next generations of humankind – one branch for each of the nine paths – making her the mother of all nations to ease her pain.

MERMAIDS, SELKIESand Spirits of the Deep

The folklore of the sea is filled with tales of half-human hybrids; these creatures, often exceedingly beautiful in either looks or voice, exact a strong allure over those they come into contact with. Whether beguiling with their beauty or with the exquisite nature of their singing, these creatures can be both benign and terrifying, helping humans if it serves their purpose, or luring them to a wet and watery end if the mood takes them.

Seductress or Saviour?The Timeless Lure of the Mermaid

Tales of mermaids have frequented folklore, children’s literature and popular culture in recent times. The origins of these long long-haired, fish-tailed, half-human beauties, however, stretch back surprisingly far into history.

An Assyrian myth from 1000 BCE tells of Atargatis, a beautiful fertility goddess. One of the many tellings of her story describes how she fell in love with a handsome young man, but tragedy was not far behind. Some say he was unable to keep up with her love-making, while other versions of the tale say that it was the birth of her human child that caused her great shame. Whatever the cause, the outcome was the same: Atargatis killed her lover and, unable to stand the guilt, she threw herself into the sea. Her desire was to become a fish in penance for her terrible actions, but it was not to be. Her beauty meant that the transformation could only be half-complete, and the grieving goddess found herself with her old human head and body but, below the waist, with the tail of a fish.

From then onwards, mermaids have become a staple of popular culture and belief, spreading throughout the world in numerous forms and incarnations. Some mermaids were said to have shown kindness towards humans. The mermaid encountered by an old man in Cury, Cornwall, rewarded his lack of greed by granting him many mysterious powers and bequeathing a magic comb that was passed down through the generations of his family. More often than not, however, mermaids receive bad press and their relationships with humans are reported as decidedly negative; for instance, the Brazilian Iara or Yara is known for tempting sailors down to her palace under the waves to a watery end.

Christopher Columbus famously recorded a sighting during a voyage in 1493, declaring the ‘mermaids’ he had witnessed as: ‘Not half as beautiful as they are painted.’ This scathing assessment might be explained scientifically; it has since been thought that what he had actually seen were manatees, sea cows or dugongs.

Perhaps the best-known and most well-loved mermaid is Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid, a story inspired by earlier mermaid folk tales, in which the famous storyteller used fairy-tale tropes to conjure a magical narrative beloved by many today. Written in 1836 and published the following year, Andersen’s mermaid has been represented in dozens of incarnations and variations over the almost two centuries since she first appeared on the printed page. Often reimagined and retold for modern audiences, the tale is one of many now at the centre of debates about gender, sexuality and feminism in folk tales and literary fairy tales. The mermaid is commemorated today by a statue that rests at Langelinie, Copenhagen, Denmark; fashioned out of bronze, she is a copy of the original designed by Edvard Eriksen and erected in 1913.

The Little Mermaid:A Tale from Denmark

Once there was a mermaid, the youngest of six princesses, who lived in a beautiful kingdom beneath the sea. Her mother was dead, but her father, the Merman King, ruled with the support of their grandmother from a breathtaking palace made of coral and amber and a mussel-shell roof. Although the youngest of the sisters, she was the most contemplative, calm and content.

Each of the princesses had a small garden, and while the others filled theirs with all manner of beautiful things, the youngest mermaid had nothing in hers but flowers that were like the sun and a marble statue of a beautiful boy. She was greatly taken with the human world above, begging for tales from anyone who might know anything of what went on there. Such stories only increased her fascination, and the little mermaid longed to see it for herself. This was not a forlorn hope; when each princess reached the age of 15 they were permitted to rise up above the waves and sit on the rocks by night, to watch the ships and experience a little of the world of humankind.

One by one her sisters had their turn, and the youngest mermaid watched and waited and listened to their experiences, each passing year only increasing her desire and longing to see for herself. Finally, when she felt she could wait no longer, her turn came. Sunset had just passed when the little mermaid rose up through the ocean for the first time, to find a calm sea and golden streaks fading in the sky. Drinking in the fascinating sights, the sound of a party in full swing on a nearby ship caught her attention; captivated, she swam closer for a better look.

She spied a young prince celebrating his birthday, and, to the mermaid, he was the most attractive sight she had ever seen. She watched and watched, enjoying the brightly coloured rockets that were set off in his honour, the lights and flashes and gaiety little short of magic in her eyes. The mermaid could not tear herself away even after the last strains of music had long faded, the ship now in darkness as the night went on. So she was there to witness the sudden breaking of the calm: an unexpected storm rolling in, shattering the peace of the night. Waves crashed higher and higher, rolling over the deck, the ship at the mercy of the tempest.

As the little mermaid looked on, the main mast was snapped like a piece of kindling, the helpless vessel tossed onto its side as those onboard flailed desperately in the water. Despite great danger from floating debris, the little mermaid found the prince, holding his head out of the water and keeping him safe as the storm finally died down. As dawn broke she took her precious prize to the nearest land, setting him on the beach carefully before retreating to watch. Before long, the prince was discovered by a young woman, who ran for help, and the mermaid watched sadly from behind a rock as he was carried off to warmth and safety.

The mermaid returned to her home but could not forget the prince; quiet and withdrawn, she pined for the young man and the world she had left him to. When she admitted the cause of her sadness to a sister, word soon spread, and it was revealed that the location of the prince’s kingdom was known to another mermaid. The princesses took their sister there, and the little mermaid now spent her evenings near the palace, watching what went on there and waiting for glimpses of her prince. Instead of soothing her troubled heart, more and more she wished for an immortal soul like humans possessed; alas, being a mermaid, this was not to be. Instead, like any mermaid, she was destined to spend 300 years beneath the waves, before her form would be dissolved into foam.

Was there nothing she could do to gain a soul, she asked her grandmother one day in despair. There was only one thing, the old woman told her: if a mortal man loved her more than anything in the world and married her, her body would then become infused with his soul and she would achieve her wish. It could not be, however, for she had only a tail – and how could a mortal man love someone who is half fish?

That night the mermaid decided to seek help elsewhere. There was a terrible sea witch known for her great powers, and the mermaid set off to ask for her advice. The journey was terrifying and hard, through bare grey sands and bubbling mud, with trees and bushes that were alive, grabbing and pulling at those unwary enough to get too close. Horrified, the mermaid saw in the mud the bones of animals and humans who had drowned. It was so tempting to turn back and return to her lovely home, but the determined little mermaid continued on her way.

Finally she reached the house of the sea witch, who already knew the reason for her visit. It was foolishness, declared the witch, but if she was determined to go through with it, there was a way that it could be done. To swap her tail for human legs and have the chance to gain an immortal soul and be with her prince, the witch would make her a potion; before sunrise came she must swim ashore, sit on the beach and drink it. Her tail would then divide and shrivel, becoming instead the two legs she so coveted. It would come at a price, however, the witch warned. The process would be painful and feel like she was being run through with a sword. Not only that, every step the mermaid took on her new feet would feel like treading upon knives as she went. She would, however, without doubt, be the most beautiful girl the kingdom had ever seen.

A more faint-hearted girl might have balked at this, but the mermaid stood firm and agreed, her love for the prince so great she was willing to suffer anything to have the chance to win his heart. She would not be able to reverse the process, the witch warned: she would never be a mermaid again and would therefore never see her family under the waves. Also, if she didn’t manage to convince the prince to love her, she would not gain a soul, and on the first morning after his marriage to someone else her heart would break before she instantly turned into foam in the sea. Even to these terrible conditions the mermaid agreed, but there was yet more. As payment, the sea witch demanded the girl’s beautiful voice in the form of her tongue. Again the little mermaid did not hesitate, and her tongue was duly cut out, the witch making the promised potion for her.

Grief-stricken at the thought of not seeing her family again, but hopeful for what was to come, the mermaid made her way to the beach. Drinking the potion down she felt the first stab of agony course through her as the witch had promised. It did not matter, however, as the prince himself appeared at that moment and, as she looked at herself, the mermaid gleefully saw that her tail was gone, human legs now in its place.

Intrigued, the prince asked her name, but of course she could not tell him that or anything else about herself. Instead, she was taken to the palace, where she was given clothes and looked after as a valued guest. The prince became very fond of the little mermaid, and the pair were inseparable. She slept on a velvet cushion outside his room, and he took her riding with him, climbed mountains as they explored the kingdom, and she smiled and looked on him with love even as her feet bled. The prince did love her in return, but, alas, as a child, not as a future wife, and the proposal of marriage she so longed for and needed never came. For the prince confided in his silent confidante that he was in love with the girl who had discovered him on the beach after the fateful storm, and he could now love no other. This news nearly broke the mermaid’s heart, especially as without her tongue she could not tell him that it was she who had saved his life that night, and was powerless to reveal her identity.

As time went on, rumours started to circulate that a bride had been chosen for the prince. Yet the mermaid did not worry, as he had told her that because there was only one girl for him he would never wed. To keep up the pretence, however, he made the voyage to where his prospective wife lived in a neighbouring kingdom; the mermaid – his constant attendant – accompanied him on the journey. In a terrible stroke of fate for the mermaid, it turned out that the princess was the very same girl who had helped save the prince; overjoyed, the prince at once consented to marry her and preparations for a grand wedding were soon underway. The mermaid played her part with smiles and all signs of happiness, even as her feet bled and the pain in her heart grew ever greater as she knew that this marriage would bring with it her death.

One night, the mermaid received a visit from her sisters. They were barely recognizable as their hair was shorn off; out of love for the little mermaid they had made a bargain with the sea witch, swapping their hair for a knife that would save their sister’s life. She had only to stab the prince with it when he slept and the spell would be reversed; the little mermaid could then return to her 300 years as a mermaid and an end dissolving in the foam.

The mermaid took the knife and crept into the room where the prince slept, a smile on his lips as he dreamed of his new bride. Gazing down at him, she felt her heart almost burst with love, and in that moment she knew she could not carry out her task. With a final look at him she turned and left, throwing the knife far out into the sea. A moment later the mermaid followed, throwing herself into the deep water, where she dissolved into foam.

Despite the witch’s dire prediction, however, all was not over for the little mermaid. She was greeted by the daughters of the air, spirits who had been offered the chance to strive for 300 years doing good deeds in order to earn an immortal soul. If they were successful, they would reach heaven, and the little mermaid, through her suffering and selflessness, would now have the chance to do the same. Gladly, she accepted the offer, bidding farewell to the earth and sea below as she rose up into the clouds above.

THE KING OF HUMBUG:P.T BARNUM AND THE FEEJEE MERMAID

Being elusive creatures, it isn’t often that the opportunity arises to see a mermaid in the flesh. In 1842, however, visitors to New York were presented with just such a chance, when the now infamous Feejee Mermaid went on show at Barnum’s American Museum, through the connivance of arch-hoaxer P.T. Barnum. Believed to be of Japanese origin, the ‘mermaid’ – measuring an estimated 45–90cm (11/2–3ft) long – was actually the desiccated body of a monkey sewn to the back half of a fish. Despite disappointment expressed by some visitors, the exhibit was a hit, with Barnum’s profits doubling in the first month the ‘mermaid’ was on show.

Not long afterwards, the mermaid mysteriously vanished; some stories say it perished in a fire, while others are convinced that, against all odds, it escaped this ignoble fate. Is a similar mermaid in the possession of the Peabody Museum at Harvard University in fact the original Feejee Mermaid?

The Mermaid to Serpent Queen: The Many Guises of Mami Wata

Mystical, ever-changing, many things to many people; the African water deity known as Mami Wata is a complex and multifaceted spirit. Most popularly depicted as half-woman, half-fish, with long, wavy black hair, her likeness to the popular and seductive mermaid of legend and folklore is immediately inescapable, highlighting the hybrid and shifting nature of folklore between different times and continents. Her nature is like that of the sea itself: powerful, changeable, alluring, both willing to give, and to take away. She is worshipped throughout West, Central and Southern Africa, as well as within the African diasporas: throughout the Caribbean, Latin America and the USA.

Her origins are often debated, but it is generally accepted that Mami Wata is not indigenous to the African countries that have become her home over the centuries. With a long tradition of part water creature, part human deities in such areas, however, it is unsurprising that she has thrived and taken root there.

The primordial water spirit, noted for her overwhelming beauty, Tingoi (or Njaloi) has been identified as a precursor to Mami Wata, and forms the link between sea, water deity and serpent. Sometimes depicted as a mix of serpent and fish, Tingoi has the head of a human woman, long, black locks of hair and a stunning appearance, not to mention the powerful lure she holds over those who follow her, heavily suggestive of later mermaids of European lore and Mami Wata herself. Receptiveness to such beings was already present when, in the 15th century, through contact made from trade and conquest, the mermaid was taken by African peoples and reimagined, emerging as the fully African Mami Wata.

Another link between Mami Wata and mermaid lore is through the connection both have to mirrors. The image of a mermaid combing her luxurious locks while admiring her reflection is a common one, and Mami Wata is likewise often depicted with her own treasured glass. Mirrors are also used by her followers to make contact with Mami Wata; they form an important piece of Mami Wata worship and identification and are present at her shrines. Mirrors represent the reflective surface of the water, but also allude to her ability to transgress boundaries. They are said to attract her to them because of her vanity, drawing her presence to wherever she is needed. Her devotees mirror her in their worship: recreating her underwater realms within their sacred spaces, impersonating her in rituals, and even entering possession trance states to gain her favour. However similar some of her traits may seem to mermaid traditions, though, the worship of Mami Wata is very much a living belief, one that has been called a ‘uniquely African faith’ that developed in times of trade with the wider world.

In possession of many powers, Mami Wata is generous and bountiful, bestowing them upon those who follow her, well-known for bringing wealth and fortune to those she favours. Fertility is also said to be in her boon, despite her own infertile and childless state. Another power possessed by this deity is that of healing, in both body and mind. It is said that the most favoured of her followers have sometimes been taken down to her watery realm beneath the sea, returning to their life on dry land changed beyond recognition forever.

Despite her great power for good, there is a darker side to Mami Wata. While giving gifts in one moment, in the next she can and will take them away, striking with sudden wrath those who displease her. Illness, suffering beyond measure, even death itself is said to come at her hand. There is also said to be a limit to her bounty; to those she grants wealth, beauty is beyond their grasp, and those upon whom she bestows fertility, wealth will never be theirs. Mami Wata is a powerful female, nurturing and sexual potency fully co-existing within this most complex of deities. Yet she is also prone to jealousy, demanding faithful celibacy from men in Zaire in return for wealth, and it’s said in Ghana that she can even kill a man’s wife. For the Igbo of Nigeria, Mami Wata can also punish with illness, especially if feeling slighted at not receiving enough attention from her followers.

Although unpredictable, one of the many lures of Mami Wata is the very fluidity of her nature. The Krio of Sierra Leone look to the Moa River as the source of all life; the river is wild and unpredictable, mirroring the nature of Mami Wata who lives within it. Capable of morphing and being formed into whatever is needed by each individual person who calls on her, Mami Wata’s appeal is that she can be many things to many different people at any given time. Her shifting and hybrid nature is illustrated in a physical sense in an Efik sculpture of Mami Wata, where she is represented as a mixture of woman, goat and fish, while in her hands she holds a snake and a bird. In some locations, Mami Wata is found in a plural form, as Mami Watas, and even in male form as Papi Watas.

Mami Wata has enjoyed a resurgence in attention in recent years, and there has been a general increase in interest in African deities. Such interest in Mami Wata in particular has also been spurred on by popular singer Beyoncé’s fascination with the deity and allusions to Mami Wata in her album Lemonade and her own personal depiction of the goddess. An exhibition examining Mami Wata was held at UCLA in 2008, while the MAMI exhibition of 2016, held at the Knockdown Centre, New York, examined the different ways six women-identifying artists related to and identified with Mami Wata.

Some suggest that there is a less positive facet of Mami Wata: that far from empowering women of colour, the idolization of the spirit is actually harmful, reinforcing the derogatory image of Black women as ‘manipulative eye candy’. Largely, however, her reception is seen as a positive thing, capturing the imagination of and empowering many as the powerful water goddess is reinvented afresh for a modern audience.

The Selkie-folk, the Shapeshifting Seals of the Northern Seas

For those that live on the shores of the icy waters of Orkney and Shetland, the raging waves and skerries provide an atmospheric backdrop to tales of the selkie-folk. While originally dark, malevolent creatures, selkies later became renowned as beautiful and gentle, often found dancing on the sand under moonlit skies. Selkies emerge from the waves as seals, only shedding their magical skin when they reach the shore, transforming into human form as they cast it away. Many tales tell that if the skin is taken and hidden the selkie cannot return to the sea to live with their selkie-kin, and must stay in human form until it is returned.

One such folk tale is remembered in a famous Orcadian ballad, ‘The Great Silkie of Sule Skerry’. In this tragic tale, an Orkney maiden falls in love with a selkie man, who abandons her shortly after she gives birth to their child. Seven years later, a seal appears to her and tells her that he is her lover, only to dive once more into the sea. Another seven years pass, and the seal appears once more. This time he gives the gift of a golden chain to their son, who goes with him to live in the sea. The woman remarries, and many years later her husband is out hunting one day and shoots two seals. On returning to the house, he gives his wife the gold chain that he found around the neck of the younger seal. She realizes that her husband has tragically killed both her son and selkie lover.

Male selkies were often blamed for the disappearance of young women who wandered too close to the seashore alone at night. Many disappearances were put down to the girls being whisked away and taken as lovers by selkie men, who easily conquered the mortal women with their seductive powers. Indeed, women used to paint crosses on their daughter’s breasts to ward off the selkie-folk when they set out on a journey across the sea; yet a selkie lover was often coveted.

Selkie nymphs were said to have snow-white skin and large, dark eyes, and be just as irresistible as the males. Old stories say that they often sat on rocks in groups, basking in the sun, and if disturbed they would hurriedly slip back into their skins and swim away. ‘The Goodman of Wastness’ tells of a man who refused to marry a woman of his own kind, but set about stealing the skin of one unfortunate sea-maiden after stumbling upon a group of them one day. The selkies leapt into the sea and swam away, yet all but one had donned their skins and returned to their seal form. As he bundled her skin away and turned to leave, he heard the maiden weeping, begging him to give back what he had stolen. At her pleading he instantly fell in love with her, and implored her to stay with him as his wife. She agreed, but only because she couldn’t return to the sea without her skin, which he refused to return. As the years passed the couple had seven children and were content. Yet each time the man left the house his wife would search high and low for the skin that was stolen from her on that fateful day long ago. One day, when she was searching as usual, her daughter asked her what she was looking for, to which she replied, ‘A skin to make shoes from,’ to help her daughter’s injured foot. The daughter said she had seen her father take out the skin a time ago, when he thought her to be asleep. The selkie wife rushed to the place, pulled out the skin and ran to the beach. And, slipping it on, she leapt into the sea to return to her selkie husband.

Many children on the Orkney Isles have been said to have ‘selkiepaws’ – webbing between their fingers and toes. For instance, there are accounts of a 19th-century midwife who attributed this to their selkie parentage, and repeatedly cut it away to prevent fins forming from their tiny hands.

To Summon a Selkie Lover

Many folk have yearned to meet a selkie lover over the years, and when the secret method of calling one to you was uncovered, it was passed down from generation to generation as prized knowledge, as it is now passed on to you here. First, you should wait until the perfect time to meet your lover, this of course being high tide. When this time has come, you must go quickly to the ocean waves. Once you have reached the shore, you should shed seven tears into the sea – no more, and no fewer. At this, a potential selkie lover will appear in front of you in the waves. But be warned: sadness follows many who take a selkie as their life-partner, as most will always yearn for the waves until their days are done.

MONSTERS FROM THE DEEP

Tales of monstrous sea creatures span the centuries, appearing as early as the dawn of writing itself. Many sea serpents embody creation and primordial chaos, and can be found in end-times myths from across the globe – stories that tell of the end of the world. Tiamat is one of the first, described in ancient Mesopotamian tablets known as the Enûma Eliš. Seen as a great dragon, she is sometimes a creator goddess, while a symbol of primordial chaos for others – a thing that has filled humankind with dread since the earliest times. The myth tells of the joining of Tiamat, the personification of the saltwater ocean, with Apsu, the god of the fresh water. These two ruled together at the dawn of time, and were primeval waters in the cosmic abyss. Younger gods were born from this union, living within the body of the great Tiamat and making a great noise, which angered Apsu, hence he planned their demise. When the younger gods found out about his intentions, Marduk and Enki killed Apsu in revenge, and a great battle between the gods ensued, ending with Tiamat’s death – a symbol of the new gods overcoming the watery chaos that existed at the beginning of time. Marduk created the heavens and the earth from the two halves of Tiamat’s body on her death, and created people as slaves to the gods from the blood of her lover-son, Kingu.

According to Jewish tradition, the fearless Leviathan of the Talmud Bava Batra is said to be a multiple-headed sea serpent or crocodile, which emits a noxious gas from his mouth that makes the waters boil like an apothecary’s mixture. Breathing fire, his scales are his pride and his teeth are terrible. What many people haven’t heard of is his female counterpart; it was said that if the two mated the world would be destroyed, so the female was salted and preserved to be fed to the righteous at a glorious banquet on the Day of Judgement. Tasty!

Tales of primordial snakes and serpents come from many mythologies. Jörmungandr, the Midgard Serpent of Norse mythology, is one of the children of Loki along with Hel and Fenris-Wolf. He was thrown into the sea that encircles Midgard by the gods because of a prophecy that great misfortune would befall them due to Loki’s offspring. At this, he grew so large that his body now encircles the entire visible world and he can grasp the end of his own tail with his maw. As sworn enemies, Thor is destined to slay Jörmungandr when Ragnarök – the battle at the end of the world – arrives.

Surprisingly, giant squid are not in fact mythical sea monsters at all, despite growing to the length of a school bus; the largest ever found measured close to a colossal 18m (nearly 60ft). One legendary creature often depicted as a terrifying giant squid is the Kraken, a sea monster hailing from Scandinavia. Erik Pontoppidan, an 18th century historian, describes the Kraken as ‘round, flat, and full of arms, or branches’, with a back 2.5km (1.5 miles) in circumference. It’s said to resemble a series of small islands at first, with something floating around that looks like seaweed, and then, finally, huge tentacles as tall as a mast appear from the depths. The only way to escape his fearsome clutches is to row away before he surfaces, and then lie on your oars for safety. Apparently, fishermen have always been glad to find him, as his presence leads to an abundance of fish – yet the fishermen never stay in his vicinity for long, as even his retreat back into the sea causes whirlpools that will drag anything close down into the depths forever.

Sea monsters still capture our imagination today. A 1920s hoax told that a sea monster was to blame for the sinking of a German submarine in 1918, when Captain Günther Krech’s vessel, UB-85, was damaged by a strange beast with ‘horns, deep-set eyes and glinting teeth’. A contender for the wreck was found in 2016, yet historians from Bournemouth University said tales of sea monsters and the sinking of U-boats grew from the secrecy that surrounded precisely what took place during the first U-boat battles. Stories often arose as a result of journalists and ex-Navy men ‘talking late at night, after having a nice time’. Sea monsters appear in contemporary culture, for instance the terrifying sea serpents of Robin Hobb’s Liveship Traders trilogy (1998–2000), or the fearsome Kraken in Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest (2006), yet some reject all claims of their existence. Many dismiss them as mere oarfish turned legend, often citing the example that washed up on the shore of a Bermuda beach in 1860 – initially called a sea serpent – as evidence. Yet sea monsters linger on in our imagination, maybe as they are often perceived as spiritual symbols of the subconscious mind and our hidden fears, quietly lurking deep in our nightmares to this day.

Scylla and Charybdis

We’ve all heard people say they’re stuck ‘between Scylla and Charybdis’, but do you know there’s more to the phrase than just being ‘between a rock and a hard place’? In Greek mythology, Scylla was a terrifying monster that lurked in a cave on the Calabrian side of the Strait of Messina in southern Italy, while Charybdis lived on the Sicilian side.

Tales tell that Charybdis was a feared whirlpool that vomited ships and drowned seafarers by sucking water down to the depths of the abyss, then hurling them back up, ‘lashing the stars with waves’.

Scylla was said to be a creature with a human face, with the tails of dolphins, while her nether regions were surrounded by the heads of ravenous dogs – yet this wasn’t always so. Hers is a woeful tale of a beautiful virgin and a lover scorned. On being pursued by Glaucus, an unrelenting suitor, she was horrified to see his tail, making her question whether he was a god or a monster. Glaucus explained that he was certainly an equal of the watery gods. When sorting his catch in a field after fishing one day, he saw the fish eating the grass and then miraculously returning to the sea. On seeing this wonder he too ate a little and was then compelled to plunge into the waves forever. The gentle powers of the ocean took him as their brother, and prayed to Tethys to purge his mortal, earthly parts away by repeatedly reading a secret charm. Glaucus bathed in 100 streams, and became of the sea for evermore: falling into dark oblivion, he woke with a sea-green beard, azure skin and a fishy tail. At this story, Scylla scorned his love and fled. Glaucus went to the monstrous realms of the sorceress Circe to plead for one of her baneful love potions that would ensure that Scylla should feel the same agonies of love as he did. Hearing this, Circe revealed her own desires for him, and when rejected, vowed her revenge. Circe went to the cave where Scylla had sought shelter and poisoned the water there. Scylla was transformed into a monster forever, as her destiny decreed.

From that day hence, Scylla has plucked sailors from any passing ship that drew near to her to avoid the dreaded Charybdis, devouring them alive as the screams of her ‘dark blue ocean hounds’ echo from the cave walls. Indeed, Odysseus himself had to navigate between the two monsters, and was advised by Circe to sail closer to Scylla, or risk losing his entire ship to Charybdis. He took her advice and only six of his crew died – one apiece eaten raw by each of Scylla’s heads. Many have rationalized Scylla as the treacherous rocks of the Italian coast, which do indeed devour wayward ships.

ISLANDS OF FABLE AND MYTH

W