11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

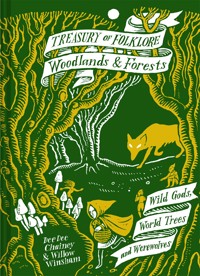

- Serie: Treasury of Folklore

- Sprache: Englisch

An entertaining and enthralling collection of myths, tales and traditions surrounding our trees, woodlands and forests from around the world. From the dark, gnarled woodlands of the north, to the humid jungles of the southern lands, trees have captured humanity's imagination for millennia. Filled with primal gods and goddesses, dryads and the fairy tales of old, the forests still beckon to us, offering sanctuary, mystery and more than a little mischievous trickery. From insatiable cannibalistic children hewn from logs, to lumberjack lore, and the spine-chilling legend of Bloody Mary, there is much to be found between the branches. Come into the trees; witches, seductive spirits and big, bad wolves await you. With this book, Folklore Thursday aim to encourage a sense of belonging across all cultures by showing how much we all have in common.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 234

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Introduction

Part One: Into the Trees

The World Tree

Yggdrasil

The Sky-High Tree

Trees and Tengriism

The Yaxche

Trees of Myth and Mystery from Around the World

Baobab Trees

Pine Trees

Yew Trees

Dragon’s Blood Trees

Cedar Trees

Banyan Trees

The Marvellous Mushrooms of the Forest Floor

The Trees of Christmas

Charring the Old Wife and Other Customs: The Magic of the Yule Log

Tió de Nadal: The Defecating Christmas Log

Blessing the Trees and Ensuring the Harvest: The Tradition of Apple Wassailing

Part Two: Woodland Creatures

Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?

The Last Wolf in Britain

Little Red Riding Hood

Creatures of the Night: The Curse of the Werewolf

Bears, Gods and Heroes

Snow-White and Rose-Red

Bear Worship

Virgins, Huntsmen and Jesus Christ: The Quest for the Unicorn

Jackalopes and Wolpertingers: Creating a Legend

What Lurks in the Lumberwoods: The Most Fearsome of Critters

The Squonk

The Hodag

The Hidebehind

The Silver Cat

The Rumptifusel

The Splinter Cat

Part Three: Folk of the Forests

A Giant Among Lumberjacks: Paul Bunyan and the North American Lumber Camps

Little Otik: Folk Horror from the Forests

Lords of the Wild

The Forest God Tapio, Finnish

The Leshy, Slavic

Herne the Hunter, English

Papa Bois, Caribbean

At One with the Trees: Tree Nymphs and Spirits

Penghou

Dryads and Hamadryads

Moss People

Kodama

Hulder and Skogsrå

Nang Tani

Forest Hags from Around the World

Cannibals, Demons and Witches: Top Five Forest Hags

Bloody Mary: The Legend of Mary Worth

Fearlessness in the Forests

The Women Who Turn into Trees

The Handless Maiden

Conclusion

Authors’ Note

Acknowledgements

References

Index

INTRODUCTION

Trees are the lifeblood of the earth. Their roots run deep in the soil; they are the veins and arteries of our planet, sustaining and nourishing the life of the ground around them. Their very existence replenishes the air we breathe, creating oxygen that sustains most life on our little planet. We are only now beginning to understand the intricate network of trees that cover the land, and how they are able to communicate with each other. Yet the ancients somehow knew this, without the science we have today. They saw how the trees’ branches reached up to touch the heavens, gave a home to the birds of the air. They saw how they dug deep into the soil below us, connecting the skies and the land we walk upon; often stretching out as far as the eye could see, fading into horizons, deep and unknown. Since humanity first walked this earth, the trees have provided sustenance, and we have relied on them to provide our food, from the berries and mushrooms that grow within them, to the animals our ancestors hunted between their trunks. They provide fuel for warmth, and timber for our shelters, and for the boats that first carried both people and their wares to distant shores.

Strangely, while the trees were once a way for us to communicate with both spirits and gods, now, in the modern day, trees are used to communicate our words to others and share our ideas across the globe. The book you are now reading was once part of a tree.

And still, we forget them. We cut them down. We burn them, and mould them, and shape them again and again. Yet as we do, their stories linger. We carry the essence of trees with us always. A memory; a tale half-remembered from childhood; a tradition from times long gone, a custom of yesteryear that had meaning once, way back when, before we ourselves were born. Wherever we live in the world, most of us have woodlands – or even a single tree – that we call our own; trees that we have loved since childhood. They might be horse chestnuts that bear the conkers of our childhood games, conjuring images of soaking the leathery brown balls in vinegar to outrank our rivals, rapping the knuckles of children across Britain. Sometimes they are the argan trees of Morocco with goats clamouring in their branches – something that may seem strange to all but those who know the secrets of the traditions that surround them. For some, they are the great firs of the northern forests, with wild boar snuffling in their snow-covered undergrowth. For others, they are the olive groves of southern Italy, with their gnarled, twisting trunks and roots that venture far into the red earth below them. Wherever we are in the world, our relationship with our trees is symbiotic, irreplicable and timeless.

Come with us now on a journey into the forests; walk with us as we delve into the tales and traditions enfolded within the woodlands of the world. Pick up your lantern and step into the dark branches as we dig deep into the soil to unearth their mysteries. There are stories to be heard, so listen softly, and you will hear the tales the leaves of ages whisper into the wind ...

THE WORLD TREE

For thousands of years people have conjured images of the outermost reaches of the universe they lived within. For many cultures, the cosmos took the shape of a tree, with its branches reaching up to kiss the heavens, and its roots twisting down into the soil of existence. This is what rooted them to their reality and shaped how they saw the world around them. This world tree was at the very core of everything they believed, an indication of how trees have been at the heart of human life since the beginnings of time. We are all creatures of the forests, yet the world trees that span the mythologies of Europe, Mesoamerica and the Near East show how many of us, once, were also people of the trees.

The world tree looks different across the globe, but many similarities exist. Usually, the trees’ branches stretch up, extending into the clouds and beyond, often with a bird at the top. The roots delve deep into the earth, or lie in water, and here there is usually an underworld beast lurking in the depths, symbolizing chaos and creation. In the middle exists the world of humankind. The number of realms or planes the tree encompasses often varies, yet one thing is constant: the tree is timeless and connects all of us to each other and the creatures and spirits of the world. It is a thing of gods, spirits and humankind; it is the place where the spiritual, intangible and physical meet. The world tree is part of the concept of the axis mundi – the axis or central pivot that the world revolves around. In some mythologies, a mountain or pillar plays a similar role to this tree. In Baltic mythology, the saules koks – tree of the sun – is an apple, linden or oak that is entirely silver or gold. Many have searched for it in legends, but no one has ever seen it. In the Batak religion, the banyan tree is seen as bringing the layers of the universe together. Hindu texts also talk of a cosmic tree, a topsy-turvy growing banyan, with the roots in heaven, and branches reaching down to bless the earth.

Yggdrasil

For some, the most famous world tree is Yggdrasil of Norse mythology, said to be an evergreen ash in the poem ‘Völuspá’ from the Poetic Edda. Within it lie the nine worlds of the Norse cosmos; some appear vertically along its trunk, while others are arranged horizontally. The realm of the gods lies at the top, the worlds of humankind and giants at the middle, and the underworld at the bottom. The tree is known by the kennings ‘Odin’s horse’ and ‘Odin’s gallows’, as he sacrificed himself by hanging upon it. Its top is so high that it reaches above the clouds and is snow-capped, while winds tear around its branches.

Three roots delve deep into watery places beneath the tree, and different sources say that they are in different locations. One lies over Mímir’s well of wisdom, where the god Odin sacrificed his eye for a drink of the waters. It crosses into the land of the rime giants, which was once where the yawning primordial void of Ginnungagap could be found.

Another root is over the spring Hvergelmir, meaning ‘the Cauldron-Roaring’. This is in Niflheim, a place of mist, cold and ice. It is here that Níðhöggr the monstrous serpent gnaws at the tree’s roots from the dark mountains of the underworld, and sucking the blood of the slain. Hel lives under this root in her underworld realm of the same name, a place of darkness and the dead, some believe to be underground. Hel is sometimes seen as the goddess of death in Norse mythology, a giantess who rules over the portion of the dead who were not taken off to other realms on their passing. It is said half the warriors who fall in battle go to Valhalla, the ‘Hall of the Slain’, ruled over by Odin. The other half go to Fólkvangr, the field of the goddess Freyja; women who have faced a noble death can also reside here in the afterlife. The 13th-century Icelandic scholar Snorri tells us at one point that those who die of illness or old age are taken by Hel, yet many suggest he often exaggerated original sources of Norse mythology, while others say he invented his own lore. We do know that Hel is the daughter of Loki and Angrboðr the giantess, cast out by the gods with her siblings, Fenrir the wolf, and the Midgard Serpent, Jörmungandr. It is said that she is half white, and half black like a decaying corpse.

The poem ‘Grimnismol’ tells us that beneath the last root is the land of men, while ‘Gylfaginning’ tells us one is over the well of Urðr in the heavens among the gods, belonging to the three norns who weave the fate of humanity: Urðr, Verðandi, and Skuld – representing the past, the present and the future. It is here that the Æsir gods come each day over the rainbow bridge Bifröst to hold court and conduct their business. At the top of the tree is Hlithskjolf, meaning ‘Gate-shelf’. This is Odin’s tower, where he sits with his ravens, Huginn (meaning ‘thought’) and Muninn (‘memory’ or ‘mind’), and watches over all of the nine worlds from the heavens. From here, he sees all – from everything humankind does, to the acts of the gods.

Many animals live among the branches of Yggdrasil. An eagle resides at the top of the tree, and a chattering squirrel, Ratatoskr, runs up and down passing messages between it and Níðhöggr the serpent. The stag Eikþyrnir feeds from the branches of the tree from the top of the hall of Valhalla, the afterlife home of warriors who died in battle. The goat Heiðrún also grazes on its leaves. While both the stag and goat feed from the tree named Læraðr, many identify this as Yggdrasil itself.

When the tree shivers and groans it is said that Ragnarok, the end time, is near.

The Sky-High Tree

The Hungarian world tree, égig éro fa, is less well known, but just as magical. It’s said that it grows from the mountain of the world, connecting the upper, middle and lower realms, and both the sun and moon are held within its branches. Snakes, worms and toads live in the roots, and at the top sits a bird, often the mythical turul, the falcon-like bird of prey often seen as a national symbol of Hungary. The tree itself is thought to grow from an animal: a deer or horse.

Many believe the tree has shamanic overtones, showing how people can travel through different realms, of which there are often seven or nine. The ability to climb the tree is restricted to the chosen folk heroes – namely the táltosok, shaman-like figures in Hungarian tradition. A táltos is usually marked at birth to follow the path by being born with teeth or a caul (a portion of tissue or amniotic membrane attached to their head) or having an extra finger. Other signs include late weaning, speaking little, and being withdrawn and aloof, yet very strong. In some regions, an individual would have to pass a test, sometimes climbing a ladder in Nagyszalonta (now Salonta, Romania), or a tree in Hajdú-Bihar county in Hungary. It’s said that a táltos can reach out to the bird and send it to discover anything they want to know.

Many know it as the ‘sky-high tree’, or ‘tree without a top’, and its tales are reminiscent of Enid Blyton’s Magic Faraway Tree collection; in these, folk-tale characters find small doors and cottages as they climb. The stories about it are often Jack-in-the-Beanstalk-like tales of fairies and castles. One tells of an unlikely hero rescuing a princess from the evil clutches of the dragon who lives above it. Another reveals that both heaven and hell can be seen when climbing the tree. Walking in the sky is a common theme, something people of the past could only dream of.

Trees and Tengriism

In ancient Turkic tradition, each tree had a spirit that was honoured and respected. Tengriism, a belief in an all-powerful sky god, was widespread. It was believed that the Tree of Life stood at the centre of the world, linking the earth to the North Star in the heavens. It was through this tree that babies would come to be born, and god would travel through it.

This is not just a thing of the distant past. Tengriism has seen a revival since the 1990s throughout Mongolia, Kazakhstan and parts of Russia, as well as the surrounding regions. While thought of as the original religion of the Turkic peoples, it is very much a living tradition. In the modern day, too, people believe in this world tree as connecting the day-to-day world with the underworld and upperworld. Today, certain trees are still seen as a sacred symbol of life that protect from evil and must never be felled. They are the centre of worship for many; strips of colourful cloth are tied to their branches, representing prayers, and people are even buried underneath them.

The Yaxche

World trees were common throughout the Mesoamerican cultures of the past. For the pre-Colombian Maya, the Ya’axché or Yaxche was a great ceiba tree that stood at the centre of the world. Various names exist for the tree depending on the specific Mayan language used. The Popul Vuh – the 16th-century cultural narrative of the K’iche’ people of Guatemala – tells that the gods placed four ceiba trees in each corner of the universe, yet the Yaxche was placed in the middle of all of them, connecting the everyday world to the underworld (Xibalba) and the sky. It represented the four cardinal directions – linked to the Mayan calendars – and was believed to support the entire universe, allowing both humans and gods to travel throughout the realms. Depictions often show the tree with birds in the branches, and a water monster at the roots.

Trees have been central to the region’s cultures for centuries. The Memorial de Sololá, a 16th-century manuscript written by Francisco Hernández Arana Xajilá, chronicles the origin of the Kaqchikel nation. Part of this is their creation epic, which tells how man fed upon the very trees themselves, their wood and leaves, when the Creator first made man from the earth. The power of the sacred Chay Abah, or Obsidian Stone, helped the Creator to make humankind. This was the oracle of the Kaqchikel nation’s sorcerers that had come from the underworld and represented the principle of life itself. The ceiba is still the national tree of Guatemala, considered sacred and central to their cultural heritage. The gods must be asked permission before cutting one down, even now. Today, having a ceiba tree in your community is to have a divine presence in your midst; it is the mother tree of the nation. One belief should be noted though: anyone who hugs this tree risks becoming just as obese as the tree itself, so beware!

TREES OF MYTH AND MYSTERYfrom Around the World

Over the centuries, trees of all sizes, colours and locations have inspired a great wealth of myths, legends and folklore. Whether revered and admired from afar or used for practical purposes, here are some of the most fabulously folkloric trees of the world.

Baobab Trees

Native to the plains regions of Africa and Australia, the very appearance of this giant is as fascinating as the folklore that surrounds it. The baobab – also aptly known as the upside-down tree or the monkey-bread tree – looks, at first glance, as if it is growing upside down. The branches, reaching high and wide, look more like roots to the onlooker, suggesting that they should therefore be reaching down into the earth. Unsurprisingly, there are many tales explaining how the tree came to have such an intriguing appearance.

Many found the sight of the baobab displeasing. The African god Thora, creator of the world, tossed the baobab out of his paradise garden. It fell to earth and started to grow, but it landed upside down. That is why it looks as it does today.

Another folk tale, this one from Namibia, tells how the Creator decided to give a different tree to each animal he had made. The hyena, late and not paying attention, found herself at the very end of the line. When she was given the last remaining tree – the baobab – the hyena was far from impressed and threw the strange-looking sapling away. It was not so easy to get rid of however and, landing upside down, the tree has grown this way ever since.

Another story suggests that the baobab itself was to blame for its upside-down appearance. The tree was said to have been very opinionated, constantly telling the Creator what it thought of his other creations – most often comments of a decidedly negative kind! In a fit of frustration, the Creator lost his temper and tore the chattering tree from the ground. Temper vented, the Creator realized that he did not want the baobab to perish; instead, he shoved it into the earth once more, but with one vital difference: the tree was upside down. If the baobab continues to voice its opinion, to this day, no one is able to hear it!

In some stories, the tree goes on to redeem itself for both its appearance and behaviour. This explains how, despite being so troublesome at its creation, the baobab tree is actually one of the most useful trees out there. Its gifts are manifold: from rope and paper being woven from the fibres of its trunk, to glue from the pollen and a potent tea or beer from the bark. The baobab can grow over 20 metres (65 feet) in height, holding the honour of being the largest succulent in the world.

It is believed among some of the indigenous peoples of Southern Africa that spirits live within the flowers of the baobab tree. If anyone is foolish enough to pick them, they will pay a harsh price: the offender will find themselves ripped apart by fierce lions.

Pine Trees

The great pine tree is nowhere revered as much as in the folklore and beliefs of Japan. This tree has long been held as a symbol of longevity and good fortune, constancy and the endless nature of existence. They are often found growing outside the gates of gardens, and lanterns hang from their branches during the Festival of the Dead. They are known for heralding good fortune. The pine remains evergreen, unchanging. The tree rests between the world of the living and that of the dead, said to protect against evil spirits and bad fortune.

Perhaps one of the best-known tales of the pine in Japan is the beautifully evocative story of the twin pine trees: there are several different variations of this story of the spirits of two eternal lovers. In the version related in one of the greatest known Noh dramas, there are two pines planted from the same seed, one at Takasago and the other some distance away in Sumiyoshi. One day a Shinto priest meets an old couple beneath the Takasago pine. They get talking, and the couple tell the priest how the man tends the pine trees in both locations, travelling between the two pines to look after them and to meet his love. As the tale continues, it is revealed that the couple are in fact the spirits of the pine trees, joined together forever.

‘The Wind in the Pine Tree’ is another version of this story. A pine tree was planted a long time ago by a deity from heaven. A young man left his home for a great journey and, as he travelled over the sea, the sound of enchanting singing reached his ears. Coming ashore, he pushed his boat back into the waves and walked on until he came to the pine tree. Beneath it sat a lovely maiden, her voice being the sound that had drawn him in. They married, and lived for many, many happy years together. Finally, old, wrinkled and happy, the couple left this life, and were received into the branches of the pine tree. They remain there to this day.

Two ancient pines that stand in the grounds of the Takasago shrine today are known as Jo or Joo and Uba – old man and old woman. They are visited frequently by couples who are hoping for a long, happy and healthy life together.

Another tale is that of the ‘Silent Pine’. When the Emperor Go-Toba found the noise of the wind blowing through a certain pine displeasing, he ordered it to stay still. The ever-obedient pine tree stopped moving and remained so from that moment onwards. Awed by such a display of compliance, the wind was never able to stir the tree again.

During wedding feasts, both male and female pine cones are displayed on tables to bring the couple a long and happy life.

Yew Trees

This tree comes with darker connections, as the yew, perhaps more than any other tree, is first and foremost associated with death and dying to our modern minds. This is not a new connotation, but one that goes back many, many years: in Celtic mythology, the yew is explicitly linked with the otherworld.

Of all the trees, the yew is, perhaps fittingly, most often to be found growing in or beside graveyards. It was once believed that the tree’s roots would grow down through the eyes of the dead buried there and keep them in their place, so they would not escape. Another burial custom associated with the yew is referenced in Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night: that of placing a sprig of yew in the shroud before burial.

One reason for this link with death is the toxic nature of the yew; its poisonous qualities are greatly attested. Again, we turn to literature to find evidence of the yew’s history, where a potion made from it is referred to as ‘juice of cursed hebenon’ in Hamlet, and ‘juice of hebon’ by Christopher Marlowe in The Jew of Malta. Hebon and variants of the word were well-known names for yew during the 16th century.

The yew tree has been a staple of the British landscape since before the last ice age. Yew wood was the wood of choice for longbows in medieval England. In Yorkshire, in the north of the country, a legend tells how a young maiden who did not pay attention to the address of the local priest met a terrible end when the slighted cleric decapitated her. To conceal his crime, the priest hid the girl’s head within a yew tree. In the years that followed this awful deed, the tree took on a holy significance, attracting pilgrims who collected branches from it to take with them. The reason? The ‘hairs’ between bark and wood were said to be those of the murdered maiden.

In Dibden, Hampshire, a large yew was prominent in the churchyard there until the early 19th century. The tree was known as Lady Lisle’s yew, due to the fact that the ill-fated noblewoman, wanted for treason, was said to have been taken prisoner as she tried to conceal herself within its branches. Her attempts were to no avail: she was captured and executed in Winchester marketplace on 2 September 1685. In the 19th century it was believed her spirit remained at the yew, two hundred years after her death – it was said that she drove four headless horses around the tree when the moon was covered.

In Nevern, Wales, the churchyard is home to some yews with a mysterious history. Lining the path to the front of the church, these trees are said to be around seven hundred years old. One of these is known as the Bleeding Yew, after the blood-red sap that is seen to seep from it. There are many explanations and stories that try to explain this strange sight, the most common being that the tree bleeds in sympathy with the crucified Christ.

Another famous example is the Fortingall Yew in Scotland. According to legend, this tree has links to Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor who washed his hands of Jesus and sentenced him to death. Depending on which version you listen to, Pilate was either born beneath the yew itself, or enjoyed many a playtime in its branches as a small child. Or perhaps both!

Dragon’s Blood Trees

The Dracaena or dragon genus – believed to contain upwards of one hundred species – is as fascinating as its name suggests. Named after the blood-red sap that is seen when the tree is scratched or injured, certain trees within the genus are known as the dragon tree or dragon’s blood tree, inspiring legends and having many uses since ancient times. Their shape resembles an umbrella.

Found exclusively in Yemen, in the Socotra archipelago, the species Dracaena cinnabari has a long history. Resin from these trees, a valued commodity, was traded by Rome from at least the 1st century BCE. The famed resin was also mentioned by Pliny. Today, small amounts of their berries are fed to livestock for health purposes. Socotra itself has a rich wealth of folklore attached, and it is known as the ‘island of the phoenix’ and the ‘island abode of bliss’.

Another dragon tree, the Dracaena draco, is found on the Spanish island of Tenerife growing in semi-desert areas. Tenerife is home to the largest-known dragon tree in existence: El Drago Milenario, ‘The Thousand-Year-Old Dragon’, in north-west Tenerife. There has been considerable confusion and debate regarding the exact age of this tree: although estimated to be several thousand years old in the late 19th century, it was later concluded that the oldest dragon trees in Tenerife were in fact no older than three hundred years. It is now thought that the tree, and its fellow dragon trees, could be anything from three hundred years old to a thousand. Indigenous Guanches used the sap from dragon trees to embalm the dead and worshipped them specifically.

In Greek mythology, the existence of the dragon tree is explained. Hera set the serpent-like dragon Ladon to guard the golden apples of Hesperides that she had given to Zeus as a wedding gift. All went well until Heracles – or Hercules as he is sometimes better known – came along. Of the twelve labours he was tasked to carry out, the penultimate was to steal the sacred apples that Ladon guarded so carefully. Unfortunately for Hera and the dragon, Hercules was successful: finding Ladon curled around the tree he slayed the guardian, spilling his blood all over the ground. As it flowed and flowed, trees sprang up where