10,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

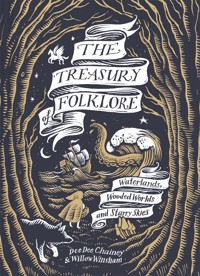

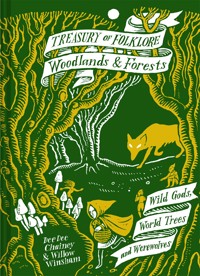

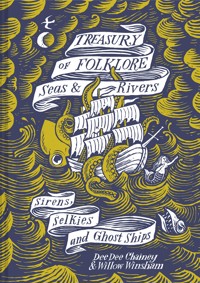

- Serie: Treasury of Folklore

- Sprache: Englisch

Enthralling tales of the sea, rivers and lakes from around the globe. Folklore of the seas and rivers has a resonance in cultures all over the world. Watery hopes, fears and dreams are shared by all peoples where rivers flow and waves crash. This fascinating book covers English sailor superstitions and shape-shifting pink dolphins of the Amazon, Scylla and Charybdis, the many guises of Mami Wata, the tale of the Yoruba River spirit, the water horses of the Scottish lochs, the infamous mystery of the Bermuda Triangle, and much more. Accompanied by stunning woodcut illustrations, popular authors Dee Dee Chainey and Willow Winsham explore the deep history and enduring significance of water folklore the world over, from mermaids, selkies and sirens to ghostly ships and the fountains of youth. With this book, Folklore Thursday aims to encourage a sense of belonging across all cultures by showing how much we all have in common.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 222

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Dedicated to everyone who has contributed to the #FolkloreThursday magic over the years.

CONTENTS

Part One

Treasures, Seduction and Death: The Lure of the Ocean Waves

The Seas and Oceans

Famous Floods

Mermaids, Selkies and Sirens

Seductress or Saviour? The Timeless Lure of the Mermaid

The Little Mermaid: A Tale from Denmark

The Call of the Siren

The Selkie-folk, the Shapeshifting Seals of the Northern Seas

From Mermaid to Serpent Queen: The Many Guises of Mami Wata

The Fabled Coast of Puglia

The Legend of Cristalda and Pizzomunno

The Dolphin of Taranto

The Priestess Io and the Ionian Sea

Monsters from the Deep

Scylla and Charybdis

Islands of Fable and Myth

Maui, Demi-God and Creator of Islands

Claimed by the Waves: Underwater Worlds

The Lost City of Ys

The German Atlantis: The Lost City of Vineta

Urashima Tarõ and the Palace of the Dragon King

Scheherazade’s Tales: One Thousand and One Nights

The Fisherman and the Jinni

The Tale of the Ensorcelled Prince

Reversal of Fortune: The Lady of Stavoren

Red Sky at Night: Sailor Superstitions from Across the Globe

Haunting the Waves: Ghostly Ships and Skeleton Crews

The Graveyard of the Atlantic: The Mystery of the Bermuda Triangle

Of Coffins, Rogues and Priests: Smuggling Around England’s Coasts

Part Two

What Lurks Beneath: Sacred Rivers & Mysterious Lakes

Rivers and Lakes

Sacred Rivers

Rivers of the Underworld

Greek

Korean

Norse

Forgotten Waters: The Hidden Rivers of London

Waterfall Folklore

The Maid of the Mist

The Dragon’s Gate

Lover’s Leap: Suicidal Lovers

Oba’s Ear: A Tale of the Yoruba River Spirit

The Mysterious Waters of Scotland

Water Horses: Majestic and Malevolent Creatures from the Depths

Humped Serpents and Vicious Eels: Loch Ness and the World’s Most Fearsome Lake Monsters

Ogopogo

Folklore or Fakelore? The Monster of Bear Lake

The Folklore of Swamps and Marshes

Sinister Bog Lights: Will-o’-the-Wisp

Be Careful Where You Rest: The Insatiable Appetite of the Irish Joint Eater

Well Folklore

The Fountain of Youth

Myth and Mystery: The Lady of the Lake

Conclusion: What Can We Learn from Our Seas and Rivers?

Acknowledgements

References

Index

THE SEAS AND OCEANS

From the earliest times, the sea has been a major part of life for many people around the globe. Humans walked across continents, and traversed the seas, to settle the shores of distant lands that belonged only to the beasts of the earth. Since the ice receded, and tundra spread over our planet, island and coastal communities sprang up whose lives and livelihoods relied on the sea, as they still do today. Throughout the world, from the windy cliffs of Cornwall in England to the furthest reaches of the Philippines, we see that life on the coast is well and truly alive. Cornish folk bands, like the Fisherman’s Friends of Port Isaac, sing shanties passed on by their grandfathers as they trawl the cold waves of the Celtic Sea, and they know all the stories of their shores, from Land’s End to the Lizard. While far away, on the other side of the globe, Sama-Bajau fishermen watch the same sun set after their day on the waves, yet there will be no return to land for them: they reside in their boats, living a nomadic lifestyle under the ever-watching Southeast Asian skies.

From time immemorial, people have known that the sea gives life; yet we are also aware that the dark waves can take it away just as easily. In early times, the gods and goddesses of the sea were blamed for withholding food and causing death. No poem fills the soul with fear so much as The Rime of the Ancient Mariner – with its threat of drowning, starvation and the wrath of the gods of the ancient seas. This poem conjures the scourge that would befall sailors if they transgressed the bounds of superstition, and the well-known rules of the lore of luck, which governed their life on the ocean waves. A symbol of the subconscious mind, the sea has always ebbed and flowed. While filled with fear, danger and death, it also stirs unspoken longings for secret lovers, unbridled lust, and yearnings for another life in the bejewelled palaces of the sea. As people stare off into the curved horizon, disappearing as a watery pathway to the unknown, they dream of far-off shores and distant lands. The sea always offered an answer to the dreary lives of many who felt their lives on the land offered little more than tilling the soil while still slaves to starvation, mired in the mud of a gruelling life with the plough.

Love is often linked with the sea, and tales abound where sailors are tempted by sirens or wily mermaids. In many stories abduction masquerades as love – a constant threat to lonely youths who wander the coasts at night. Many of these are taken captive by mermen, stolen by selkies, or dragged off to Finfolkaheem, the underwater home of the sinister finmen who lurk around the shores of Orkney and Scandinavia, eagerly trying to snatch a beguiling innocent to their fate. The Blue Men of Minch are a further horror to be faced by wayward seafarers in the waters of the Outer Hebrides. Also known as storm kelpies due to their ability to rouse tempests out at sea, it’s said that they wait patiently for sailors to drag beneath the waves, luring ships to their fate in the watery depths.

FUNAYŪREI: THE VENGEFUL DROWNED SAILORS OF JAPAN

When out at sea on rainy days in Japan, particularly on the night of a new moon, it is wise to take precautions against Funayurei – those remnants of drowned sailors who are still intent on taking revenge on others for their lost lives, and adventures cut short, by ladling water into boats with a view to sinking them. One must remember to always carry some onigiri, or rice balls, that can be thrown into the sea to ward off such horrors. If rice balls are unavailable, another solution is to prepare a hishaku, or water ladle used in the tea ceremony, with a missing bottom – a sure way to protect yourself from these watery fiends.

Yet, for others, the sea is cathartic. In many flood myths the rains come, and the overcrowded earth is submerged as the waters renew and cleanse the world of the impious and unworthy, making it ready for a new dawn of humanity. From folklore, myths and legends we can see that humanity has always viewed the sea as majestic, with a power to consume all; a regenerative, creative force that churns outside the bounds of time, roaring its way through land, animals and humans alike. In the face of this, people look at the sea with an all-consuming awe, and see the gods and goddesses of creation shimmering in its depths.

As a realm of the gods, and a source of life for many, it is unsurprising that even today people revere the ocean and give offerings to it. Hindus in Bali still submerge holy statues of gods and ancestors in the sea to purify them and imbue them with supernatural powers in a ceremony called Melasti. Similarly, Jews cast off their sins into the depths by reciting prayers and throwing breadcrumbs into the sea during Rosh Hashanah – the beginning of the Jewish new year. In Rio de Janeiro, New Year’s Eve is celebrated with the festival of Iemanjá, where offerings for the goddess are sent in boats to the sea; it is believed that if she chooses to accept the offerings they will sink, and the supplicant’s wishes will be granted. A similar sight can be seen annually in France, when each year people from the many Romani communities arrive in Aix-en-Provence on a pilgrimage route, in order to give offerings to their saint, Sara-la-Kali, in a procession to the ocean. On Shetland the relatively modern festival of Up Helly Aa marks their new year. There, too, huge boats are constructed – resembling Viking longships – and sent out to the sea in flames to the beating of drums and the sound of trumpets.

OFFERING FOR THE SEA IN POLYNESIA

Some communities take this idea of offerings and purification further; Polynesians will ritually dispose of umbilical cords in the sea. It’s also believed that pregnant mothers should never salt or string fish.

For thousands of years, great heroes and heroines from across the globe have traversed the seven seas, battling pirates and monsters for the prize of treasure, fame and the promise of a life of adventure and the lure of exotic shores. On their voyages, archetypal heroes are often favoured by gods of the sea and are witness to miraculous beasts, underwater worlds and palaces, and to fabled islands. One place that has been named as just such an island, time and time again, is Malta. Some say it might have been the inspiration for Atlantis due to its giant stone gantija temples, which are some of the oldest surviving remnants from the ancient world. While still disputed, others say that the Maltese island of Gozo is the fabled Ogygia, home to the sorceress Calypso. St Paul’s Island, off the Maltese coast, is believed to be the place where the Apostle Paul was shipwrecked in the Bible, while on his way to Rome in around 60CE; it is said that this is how Christianity reached the shores of Malta. Whether these heroes on great voyages seek fame, fortune or pirate treasure, it’s certain that the lure of the ocean and its secrets are as old as time itself.

A resounding theme in ocean folklore is the unknown, and the innate human fear of what one cannot see lurking under the waves in far-flung seas. Many stories tell of ghostly bells, still ringing from the depths of sunken towns that were swallowed by the sea – as if the inhabitants still go about their daily tasks, submerged under the dark waters among the waving seaweed fronds. For many on the biting shores of the Northern Hemisphere the sea is a place of raging storms, ghostly mists and strange noises that pierce the frosty beaches on dark nights – concealing hidden threats to life and land. For those in the southern seas, there are endless tales of sea monsters and temptresses in the exotic waters and sweet lagoons, who lure men to their doom. The very real fear of a fate worse than death itself lingers in the minds of many: that of being a castaway, stranded on a desert island, delirious from thirst, plummeting towards inevitable madness. Tales of shapeshifters are rife throughout the world, as if somewhere, deep within ourselves, we know that the sea cannot be trusted; it morphs and wanes with its ebb and flow, and nothing is ever as it seems. Many sailors have been afflicted by a madness called ‘calenture’, where, when they stare out to the endless stretch of the ocean waves, they see land instead, and jump over the side to their doom, where they will spend eternity in Davy Jones’ Locker on the ocean bed. Another tale is that of ships which finally discovered land, only to realize later that they were in fact resting on a turtle or whale so huge that it resembled a small island rather than any creature of the deep. In more recent times, the new threat of disappearing altogether, with a fate unknown, lingers – especially if sailing close to the North Atlantic’s Bermuda Triangle, still a widely debated mystery. Explanations for such disappearances range from tropical cyclones to being carried away by the Gulf Stream, right through to aliens, or to the area being the site of the fabled Atlantis.

When we look at sea folklore from around the world, we find it is often used to explain the unexplainable: unquenchable feelings of lust, illegitimacy, disappearance, bad luck, death, starvation, or a fruitless yield. Folklore indeed teaches us that the sea is dark, illicit and full of temptations. The ocean can offer the things of our wildest dreams – treasure, love, a different life – but to get these we must face our darkest nightmares: the terrifying things that lurk beneath the surface in our subconscious minds. When we face these, and defeat them, we win the treasures of the deep and see sights most can only dream of; yet one thing that folklore teaches – make no mistake – is that the treasures of the sea always come with a price.

Dare you delve further, reach tentatively beneath the dark swell, to see what you might find? Pirate treasures await you, yet take care when your fingers dip into the deep blackness that their tips don’t brush against steely scales lurking under the surface. And don’t forget: when you do dare to peer below the dancing waves, always listen well for the siren’s call …

FAMOUS FLOODS

Some of the most famous flood stories are those of Noah, who makes an appearance in the Christian Bible, Jewish Torah and Islamic Quran. Yet did you know that a devastating flood that almost extinguished humankind is a motif that resounds through myths from all corners of the ancient world? Many nations share a story of a great deluge, and while there are multiple versions of the myth we see common threads running through them all. Many flood myths appear to be tales of the gods’ punishment for the errant ways of humans, or for over-population, while others tell of the repopulation of the earth or human origins. One item that appears almost consistently is a boat or vessel that saves a few chosen people as a reward for their piety or wisdom, often filled with all the plants and animals needed to rejuvenate life across the earth. The stories commonly tell of a brother and sister pair, yet some have bewitching details all of their very own, unique to the land where they originate.

We find the roots of Noah’s deluge in earlier stories, like that of the ancient Near Eastern Epic of Gilgamesh, which was passed down from the Sumerians to the Assyrians and Babylonians. It describes Utnapishtim as a great ancestor who survived a terrible flood and was granted immortality. Utnapishtim was instructed by the god Enki to build a giant boat, called The Preserver of Life, on which to keep safe all the animals and plants of the earth, as everything that was not within the ship would be destroyed by a great flood. Afterwards, Utnapishtim sent out three birds: a dove, a sparrow and a raven. Only the raven did not return – a sign that the flood was over. As a reward for his faith, the gods gave him and his wife the gift of immortality.

Many of the Noah stories follow this pattern, yet some have quirky details unique to their country of origin. Noah appears in traditional Indigenous tales of the Dreamtime flood, woramba, from the Fitzroy River area of Western Australia, where it’s said that the Ark Gumana carried Noah, along with Indigenous Australians, finally settling on the flood plain of Djilinbadu. It’s believed that the idea of the ark ultimately landing in the Middle East was a lie, to keep Indigenous Australians in subservience. However, another Australian story gives a different explanation for the flood. The medicine man Grumuduk, who could call the rains and cause plants to grow and animals to be fruitful, was kidnapped by a plains tribe. On his escape he vowed that whenever he walked on an enemy’s territory, salt water would follow in his path.

Strangely, mice often find themselves in starring roles in the flood myth genre. A Russian folk tale recounts how the Devil told Noah’s wife to prepare a strong drink in order to discover Noah’s reason for building the ark, which indeed she did, finding out the secret that God had entrusted to him. She was also responsible for the Devil, who had transformed himself into a mouse, secreting himself away on the ark and gnawing holes into the bottom.

An indigenous flood story from northern Siberia also mentions mice. Here, seven people survived the flood on a boat, yet a horrendous drought followed it. They dug a hole, which filled with water, yet all but one man and one woman died from starvation; these two had eaten mice to save themselves. The whole of humankind are descendants of this pair.

The boat is a recurring symbol in many stories. In Hindu tradition, a demon stole the sacred books from Bramha; humanity, in its entirety, became corrupt, apart from the seven Nishis and Satyavrata, the prince of the maritime region. One day, when Satyavrata was bathing, the god Vishnu came to him in the form of a fish, warning him of the great deluge that would come to destroy all that was corrupt on the earth. He told Satyavrata that he would be secured in a capacious vessel, and instructed him to take with him the seven holy men, and fill it with all the plants and animals of the land. With this, Vishnu disappeared, and over the next seven days Satyavrata did as he was commanded and prepared for the waters. Indeed, within a week the rains began. The rivers broke their banks and the oceans flooded the land, bringing a large ship floating towards them. Satyavrata bundled the holy men on board, along with their families, and all the herbs and grains he had been instructed to bring, along with two of each animal. The great Vishnu came again to protect the vessel, by transforming into a giant fish and tying the boat tightly to himself to survive the flood. When the waters subsided, Vishnu killed the demon that had stolen the holy books, and taught their lessons to Satyavrata.

In the flood myth from Cameroon, the prophetic animal is a goat, rather than a fish. The tale tells that a woman was grinding flour one day and allowed a goat to lick it up. In gratitude, the goat warned her to take up her possessions and flee before the flood ensued.

Some flood stories take an even more fantastical turn. For the Soyots of the Republic of Buryatia in Russia the world is carried on the back of a giant frog or turtle. While this idea might be familiar to many, it might surprise you to know that it’s told that the creature moved just once and from this tiny act the cosmic ocean flooded the earth; in fact, the creation stories of Eastern Siberia say that if the world frog moves even a little, the world will shake violently, and earthquakes can rain down on humanity.

We also find that many myths link a worldwide flood with giants. Berossus, a Chaldean writer, astronomer and priest of Bel in Babylon in the 3rd century BCE, adds to the Noah story by describing the antediluvians that were left after the flood as a depraved race of giants; all except ‘Noa’ that is. Instead, Noa revered the gods, and resided in Syria with his three sons: Sem, Jepet and Chem. He foresaw the oncoming destruction in the stars and had set about building a ship to save his family. Remnants of the boat are still said to exist where it settled, on the peak of Gendyae or Mountain, and bitumen was still taken from it to ward off evil well into the 19th century. Similar tales of an antediluvian race of giants exist in Scandinavian flood traditions, where Odin, Vili and Ve defeated the primordial giant Ymir. All but two of the giants, Bergelmir and his wife, were killed in a great flood that arose from the blood of Ymir’s gushing wounds. All giants are descended from these two.

Stranger still, elves appear in a Chingpaw flood story from the northern region of Myanmar. In this tale, brother and sister Pawpaw Nan-chaung and Chang-hko fled to safety on a boat, taking nine cocks and nine needles with them. Once the rain had ceased, they threw one of each from the boat, until they came to the last pair. On throwing these overboard, they finally heard the cock crow and the sound of the needle hitting the bottom. With this they were able to return to dry land, and soon came upon a cave in which two elves had made their home. The siblings stayed with the elves in their cave, and all was well with them; that is until Chang-hko gave birth, and left the infant in the care of the elfin woman while she went out to work. This is where the story takes a gruesome turn: the woman was a witch! Faced with the incessant wailing of the child, the witch took it to a crossroads where nine roads met, chopped it to pieces and scattered the body about, yet keeping a little with her, with nefarious intent. On her return to the cave, the elf-witch made a curry from the remaining parts of the babe, feeding it to the unsuspecting mother. When she discovered the truth, in her utter dismay, Chang-hko fled to the crossroads to plead with the Great Spirit to avenge her child and bring it back to life. The Great Spirit deemed this impossible, but instead promised to transform the remaining pieces of her child into the next generations of humankind – one branch for each of the nine paths – making her the mother of all nations to ease her pain.

MERMAIDS, SELKIES AND SIRENS

The folklore of the sea is filled with tales of half-human hybrids; these creatures, often exceedingly beautiful in either looks or voice, exact a strong allure over those they come into contact with. Whether beguiling with their beauty or with the exquisite nature of their singing, these creatures can be both benign and terrifying, helping humans if it serves their purpose, or luring them to a wet and watery end if the mood takes them.

While there are similarities between the mermaids, selkies and sirens that fill the lore of the sea, there are telling differences, as we will discover below.

Seductress or Saviour? The Timeless Lure of the Mermaid

Tales of mermaids have frequented folklore, children’s literature and popular culture in recent times. The origins of these long long-haired, fish-tailed, half-human beauties, however, stretch back surprisingly far into history.

An Assyrian myth from 1000BCE tells of Atargatis, a beautiful fertility goddess. One of the many tellings of her story describes how she fell in love with a handsome young man, but tragedy was not far behind. Some say he was unable to keep up with her love-making, while other versions of the tale say that it was the birth of her human child that caused her great shame. Whatever the cause, the outcome was the same: Atargatis killed her lover and, unable to stand the guilt, she threw herself into the sea. Her desire was to become a fish in penance for her terrible actions, but it was not to be. Her beauty meant that the transformation could only be half-complete, and the grieving goddess found herself with her old human head and body but, below the waist, with the tail of a fish.

From then onwards, mermaids have become a staple of popular culture and belief, spreading throughout the world in numerous forms and incarnations. Some mermaids were said to have shown kindness towards humans. The mermaid encountered by an old man in Cury, Cornwall, rewarded his lack of greed by granting him many mysterious powers and bequeathing a magic comb that was passed down through the generations of his family. More often than not, however, mermaids receive bad press and their relationships with humans are reported as decidedly negative; for instance, the Brazilian Iara or Yara is known for tempting sailors down to her palace under the waves for a watery end.

Christopher Columbus famously recorded a sighting during a voyage in 1493, declaring the ‘mermaids’ he had witnessed as: ‘Not half as beautiful as they are painted.’ This scathing assessment might be explained scientifically; it has since been thought that what he had actually seen were manatees, sea cows or dugongs.

Perhaps the best-known and most well-loved mermaid is Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid, a story inspired by earlier mermaid folk tales, in which the famous storyteller used fairy-tale tropes to conjure a magical narrative beloved by many today. Written in 1836 and published the following year, Andersen’s mermaid has been represented in dozens of incarnations and variations over the almost two centuries since she first appeared on the printed page. Often reimagined and retold for modern audiences, the tale is one of many now at the centre of debates about gender, sexuality and feminism in folk tales and literary fairy tales. The mermaid is commemorated today by a statue that rests at Langelinie, Copenhagen, Denmark; fashioned out of bronze, she is a copy of the original designed by Edward Eriksen and erected in 1913.

The Little Mermaid: A Tale from Denmark

Once there was a mermaid, the youngest of six princesses, who lived in a beautiful kingdom beneath the sea. Her mother was dead, but her father, the Merman King, ruled with the support of their grandmother from a breathtaking palace made of coral and amber and a mussel-shell roof. Although the youngest of the sisters, the mermaid was the most beautiful of them all, famed for her soft skin and deep blue eyes. She was of a contemplative nature, calm and content.

Each of the princesses had a small garden, and while the others filled theirs with all manner of beautiful things, the youngest mermaid had nothing in hers but flowers that were like the sun and a marble statue of a beautiful boy. For the young mermaid was greatly taken with the human world above, begging for tales from anyone who might know anything of what went on there. Such stories only increased her fascination, and the little mermaid longed to see it for herself. This was not a forlorn hope; when each princess reached the age of 15 they were permitted to rise up above the waves and sit on the rocks by night, to watch the ships and experience a little of the world of humankind.