Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

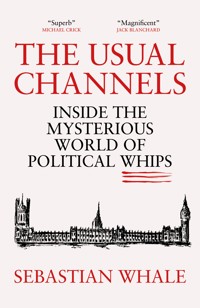

Once, political whips swore by a code of omertà… 'The theory was that you never discussed what went on in the whips' office until your dying day, as though you worked at Bletchley Park.' … But not any more. Though decades of silence have fostered intrigue, mythology and suspicion about their activities, the whips' office has long played a crucial role in Westminster, greasing the parliamentary machine and keeping rebellious MPs in check. But while whips appear all-knowing and ever-present, are they still all-powerful? The Usual Channels pulls back the curtain on one of Westminster's most notorious elements and explores whether whips still have the upper hand. Charting eccentric traditions and colourful characters, this authoritative guide is not only an insight into the workings of a crucial institution; it is also a masterclass in the past fifty years of British political history.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 769

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

iii

For Ioana

iv

Contents

History in Brief

A COLLECTION OF INTERESTING, NOTABLE AND POIGNANT DATES IN WHIPPING

1621: Sir George Calvert, one of James I’s Secretaries of State, issues what some believe to be the first recorded whip, asking for an MP’s attendance in Parliament.1

1769: The first reference to ‘whipping them in’ features in a parliamentary debate.2

1832: With the 1832 Reform Act, the role of Parliamentary Secretary to the Treasury as Government Chief Whip ‘effectively starts’, says an author and former Chief Whip.3

1836: MPs vote in Aye and No lobbies, counted by tellers. Previously, one side remained in the chamber while the other side went into the lobby and were counted on their return.4

1867: The Reform Act of the same year gives more than 1.3 million men the vote. ‘It was the first sweep of the democratic wave,’ notes a former Liberal Party Chief Whip.5

1880–81: Treasury ‘Blue Notes’ reveal that the Chief Whip administers xthe King’s ‘Secret Service Fund’ of £10,000 per year,6 until its abolishment in 1886.

1900: The Western Daily Press reports the government are accepting pairs ‘without demur’.7

1905: In reply to a parliamentary question, Prime Minister Arthur Balfour asks an MP to communicate with a colleague ‘through the usual channels’.8

1911: Conservative peer Hugh Cecil says Liberal MPs ‘vote as the party whips tell them’, since whips decide whether their expenses are paid at the election. ‘In a large measure, it is a corrupt assembly,’ he says. Senior Liberal Winston Churchill fumes: ‘That is a gross libel.’9

1918: The Representation of the People Act gives some women the right to vote. The Parliament (Qualification of Women Act) also allows women to stand for Parliament.

1919: Charles Harris, the holder of a clerical post in the government whips’ office from October 1917,10 becomes the first principal private secretary to the Government Chief Whip.

1926: Anonymous teetotal MP writes that the House of Commons is a ‘tipsy’ assembly.11

1931: Conservative politician David Margesson is appointed Government Chief Whip, beginning a nine-year tenure. ‘If one politician of the twentieth century deserves to be remembered for his work as Chief Whip, it is Margesson,’ writes an author and ex-Chief.12xi

1939: The role of principal private secretary to the Government Chief Whip formally becomes part of the civil service.

1951: Government whip Walter Bromley-Davenport mistakenly kicks the Belgian ambassador, believing him to be a Tory MP. Ted Heath replaces him in the whips’ office and in 1955 becomes Chief, credited for his handling of the Conservatives during the Suez Crisis.

1961: Freddie Warren replaces Charles Harris as principal private secretary to the Government Chief Whip.

1964: Labour MP Harriet Slater becomes the first woman appointed to serve as a government whip.

1970: Ted Heath is elected Prime Minister, five years after becoming Tory Party leader.

February 1974: Harold Wilson’s Labour Party secures four more seats than Ted Heath’s Conservatives in the general election, but not enough to secure a majority in the Commons.

October 1974: Labour secures a narrow majority victory at another general election, beginning one of the most notorious parliaments for whipping in British political history… xii

Preface

‘Sorry,’ she said. ‘You’re writing a book about…?’

The magazine editor scanned the crowded room as though searching for a place of refuge in case she’d heard me right.

‘Um, whips,’ I repeated.

‘Oh,’ she said, prosecco nearing the edge of her glass. ‘You’re writing a book about whips.’

Cornered into small talk at a book launch on London’s Savile Row, I realised, spiritually at least, that we were a long way from Westminster. ‘Yeah,’ I said. ‘Political whips.’

She dropped her shoulders and wiped faux sweat from her brow. ‘Ah! Political whips!’ Her relief morphed into another frown.

‘Do you know House of Cards?’

‘Right,’ she said, her eyes bulging with memories of Francis Urquhart. ‘Those kinds of “whips”.’

We sipped prosecco as though grateful for the distraction. She waved at no one in particular and left with: ‘Well, good luck with it.’

Many whips would be pleased that their work had gone unnoticed. Even for some MPs, what whips really get up to around the parliamentary estate remains a mystery. By design, they operate in the shadows, away from the revealing glares of camera lights and journalists’ cutting questions, their silence filled by others, their motivations and practices often ascribed.

In September 2012, Jeffrey Archer, author, peer and former Conservative MP, watched the opening night of This House, James Graham’s xivmagnificent play on the exploits of whips during the 1974–79 parliament. While leaving the National Theatre with Patrick McLoughlin, the Conservative Chief Whip until just a few weeks earlier, Archer fielded questions from reporters on what he had made of the show.

‘Patrick stood there, and nobody asked him a question because nobody knew who he was,’ Archer told me. ‘He said it was his proudest moment.’

The secrets of the whips’ office have attracted many a curious soul. Even former whips, breaching an unwritten code, have penned tomes, diaries, and articles on its history. Among them is Tim Renton, Margaret Thatcher’s last Chief Whip, who, to the dismay of his whipping contemporaries, published a part-memoir, part-study of ‘The Office’.

‘Chief Whips should never write memoirs nor give detailed interviews about their work or their flock,’ says one of Renton’s successors, who, while declining an interview, sent over musings he was happy to see published, some of which also feature in our first chapter. The man, a former Conservative Party Chief Whip, argues that holders of the position act as a ‘father confessor’ in addition to other duties. In his time, he handled ‘one coming out, three marriage problems and other personal difficulties’.

‘I would go to jail for contempt of court rather than reveal any secret of The Office or what colleagues said,’ he adds. ‘If Conservative MPs thought that whips would be writing books or giving detailed interviews, then no one would talk to us again on anything.’

For writing his book, Renton was banned from attending whips’ functions, ‘just like Peter de la Billière was banned from the SAS because he wrote a book about them’, says the former Chief.

OK, I am not comparing us to the ultra-brave men of the SAS, but the rule of trust is the same. I suppose if Chief Whips of all parties wrote detailed books, then we could outsell [former Conservative Cabinet xvminister and bestselling author] Nadine Dorries, Jilly Cooper and God knows how many Shades of Grey – but we don’t and should never do so.

Several months after this email landed in my inbox, Simon Hart, Conservative Chief Whip under Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, announced that he would publish his diaries.

Though a brave few have spilled the beans, many people who pass through The Office subscribe to its code of omertà, confidently deeming The Office a near-impregnable world.

‘Ex-whips don’t discuss The Office, so you will have to look elsewhere, I am afraid,’ said one, when I requested an interview for this book. A former Deputy Chief Whip said: ‘I have a policy of not discussing matters which occurred during the period in which I served as a government whip. Indeed, I believe that whipping, like stripping, is best done in private.’

Another Conservative whip wrote a one-word reply. ‘No.’

While it’s true that some who passed through The Office still adhere to a lifelong vow of silence, shaking their heads at those who don’t, it’s also true that times are changing. Liberated by trailblazers – and wanting to put the record straight – certain whips have, to varying degrees, opened up about their time in The Office.

Some 157 people contributed to this project, including more than sixty who passed through the whips’ office across generations; among them, eighteen Chief Whips (nineteen if you count the Lords). For what it’s worth, and despite reputations, most contributors hailed from the Conservative Party, including several Chiefs. From the outset, I contacted scores of current and former MPs, all of whom have dealt with whips to varying degrees. Anecdotes and observations about The Office poured in as though a long-closed valve had been opened.

Naturally, some needed convincing of my motives.

‘It sounds a bit like you’re going to rehash all the clichés about xviwhipping that House of Cards was particularly responsible for,’ said a former Labour Chief Whip, seizing on my assertion that I wanted to make the book ‘fun’. ‘There’s this whole sort of trope about whipping that is logged into most journalists’ computers. In the modern age, frankly, it’s completely wrong.’

This particular Chief eased up and offered a generous hour of his time.

The Usual Channels charts the past fifty years of British politics, beginning (after a run-through of the whips’ office and how it works) with the notorious 1974–79 parliament. In a sense, I pick up from where Tim Renton left off in Chief Whip: People, Power and Patronage in Westminster, which brought the story up to the 1960s.

Before we begin, some housekeeping.

Contributors’ words are in the present tense, and their roles are as they were at the time, even if the person in question went on to hold a more significant position for which they are better known (Labour Party grandee Neil Kinnock, for instance, joins our story as the MP for Bedwellty). Though many of the whips’ routines remain unchanged, some, including their hours of work, evolve throughout the book, often at odds with the practices of today’s whips as set out in the opening chapters. Rather than notifying you of every difference, the changes unfold as we progress.

Some interviewees requested anonymity to speak freely, so they are referred to by their job titles unless doing so might reveal their identity, in which case the description is more generic or obscured. Where possible, I have tried to check anecdotes or allegations with the individual concerned and put their version or rebuttal accordingly. Occasionally, this has not been feasible, whether because the person is dead, refused to comment or declined an interview. To repurpose a phrase used by members of the royal family during recent controversies: ‘Recollections may vary.’ xvii

I started this project in September 2023, although I had contemplated it ever since writing about whips for The House magazine three years earlier. Whipping, I concluded midway through the process, is politics as it really is rather than as you might want it to be. The Office gives us a window into politicians’ lives and how Parliament works. To that extent, I’ve learned more about Westminster and its occupants in the past twenty-four months than in nearly ten years of reporting.

This is The Usual Channels. Please enjoy. xviii

PART I

THE OFFICE2

Chapter 1

The Good Old Days

People often say that whipping isn’t what it used to be.

For many politicians brought up on vivid tales of twisted genitalia, foul-mouthed tirades and hoisted lapels, this is a blessed relief. For others, not least ex-whips casting a judging eye over the eroding powers left in their successors’ hands, it is a matter of regret.

‘What sort of whinging namby-pambies are some MPs these days?’ asks a former Conservative Party Chief Whip.

They complain of bullying because a whip or the Chief Whip shouted at them. Big deal… dry your eyes. I saw a Conservative MP hurled ten feet down the Committee Corridor when he had lied to his whip about voting in a committee. I thought he got off lightly.

I saw a wonderful Labour Deputy Chief Whip push one of his people against a wall, take hold of his most sensitive bits and tell him that if he ever voted with the Tories again, then he would find them in a jam jar, and a small jam jar at that.

The Chief hastens to add that he doesn’t condone violence and insists, in a typical whip’s fashion, that such behaviour never happened while he oversaw The Office. For the sake of their constituents, ‘some colleagues from all parties’, the Chief concludes, ‘should empty that jam jar and stitch them back on’.

Whipping is like other pastimes that suffer from the lament of it being different in my day. Documenters of Westminster have long 4written wistfully of a whipping regime from a bygone era, yearning for a time that may never have lived up to the mythology or, in the aspects where it did, was not revered by those who lived through it.

‘Some of us old romantics pine for a return of the good old days when the rule of law and the lynchmen reigned supreme in the Members’ Lobby – and whips were whips,’ wrote renowned Press Association journalist Chris Moncrieff in… 1986, when the Conservatives under Margaret Thatcher enjoyed a three-figure majority in the Commons. MPs from the period might be surprised to learn that whips were, in Moncrieff’s words, ‘too nice’.1

Sentimentalism aside, it is undoubtedly the case that over the past fifty years, much of the powers, methods and composition of the whips’ office have changed dramatically, illustrated in a frank conversation between two Conservative MPs who served in different eras.

Charles Walker, a popular, heart-on-sleeve-wearing backbencher, sat down with his constituency chairman, Cecil Parkinson,* who served in the whips’ office in the 1970s. That week, Walker, first elected in 2005 and into his second term as an MP, had seen the Government Chief Whip admonish a colleague on the fringes of the House of Commons chamber. Shocked not only at the flagrant nature of the public bollocking but also at the Chief’s colourful language and reddening cheeks, Walker, himself not afraid of an impassioned word or two, felt compelled to share his experience.

‘Cecil, he called him every word,’ Walker said. ‘He used the f-word and the c-word.’

‘Did he really do that?’ asked Parkinson. ‘Oh, dear. I don’t think he should have done that, Charles.’

The two men said nothing for a short time.

‘Of course, in our day, we never did that,’ Parkinson said. ‘We ruined people’s careers, but we never swore at them.’

5‘It was done without a twinkle,’ Walker says now, recalling the conversation. ‘It was just like, bloody hell!”

Though there was an element of ‘pantomime’ in Parkinson’s remark, ‘at times, it did go way over the top’, Walker says. ‘There was far less scrutiny, and I suspect some pretty unpleasant things probably never saw the light of day that you wouldn’t get away with now.’

Everything from how whips communicate to the patronage at their disposal to the location of their office on Downing Street is not what it used to be. But a key fundamental – the goal that has long underpinned the entire operation of the whips’ office – has remained the same.

‘I always describe it as being a bit like air traffic control,’ says Bridget Prentice, a Labour whip under Prime Minister Tony Blair. ‘It’s not your job to decide the worthiness of the plane; your job is to get it in the air or on the ground safely. That’s basically the role of the whips, to ensure that the government’s business gets through as close to intact as possible.’ 6

* Cecil Parkinson passed away in 2016.

Chapter 2

A Changing Tradition

What is a whip? And what do they do?

Whips oversee discipline, manage the day-to-day business in Parliament and, insofar as they can, ensure their colleagues vote in line with party policy. From political enforcers to parliamentary lubricators, whips have accrued a variety of synonyms, compared over the years by both their detractors and their advocates to the Stasi, the Broederbond and the Gestapo.

THE WHIP

The term ‘whip’ originates in hunting, where the whipper-in, a huntsman’s assistant, ‘would keep the hounds from straying by driving them back with the whip into the main body of the pack’.1 The government and opposition parties in the Commons and the Lords have a team of whips, often patrolling Westminster’s corridors and watering holes, hoovering up intel.

Historians differ over when whips and whipping came into being. In his study of Chief Whips, Tim Renton cited a 1621 letter from one of James I’s Secretaries of State requesting an MP’s attendance in Parliament as the first recorded whip. The emergence of political groupings such as the Whigs and the Tories in the late seventeenth century 8arguably solidified the need for a coordinating force in Parliament.* By the middle of the eighteenth century, the Parliamentary Secretary to the Treasury (a position held today by the Chief Whip) sent letters urging MPs to support the government of the day.2

For all the different aspects of the job, including suggesting names for promotions or demotions at reshuffles, the whips’ driving force is to deliver the government’s business. How whips encourage MPs to vote accordingly is subjective and often tailored to the individual. Some opt for gentle persuasion… others draw on personal appeals… a few might lay out the implications of a potential rebellion.

Whether MPs follow the whips’ encouragement is up to them.

‘I’ve always been very impatient with anybody who says, “The whips made me do it,”’ says former Labour Cabinet minister Harriet Harman. ‘You are the decision-maker about what you do. The whips are not your boss.’

Each Thursday afternoon, The Office distributes a circular known as ‘The Whip’ outlining the upcoming parliamentary business and expectations for attendance and votes, underlined up to three times to denote importance. A one-line whip means MPs are requested but not required to attend a vote. A two-line whip means MPs should attend unless they have a pre-approved reason for not doing so. Death may be a valid reason for missing a three-line whip, but even then, it will be on a case-by-case basis. MPs receive email invitations that update their calendars with the week ahead, giving them fewer excuses for any memory lapses or missed fine print. ‘MPs can have a reading age of about five when it suits them,’ jokes a government whips’ office insider. Unless the issue is a free vote† – meaning they can make their own decisions without fear of repercussions – MPs are expected to follow the voting instruction as set out in The Whip. Going against the leader’s 9wishes is to rebel, an act considered most egregious when done on a three-line whip, especially if not communicated to The Office beforehand. The whips, who must know how to count, do not like surprises. Neither does their party leader.

Rebel on a three-line whip and an MP could lose the right to represent the party, sitting instead as an independent in the Commons. MPs may also abstain by not voting for or against a motion,‡ viewed as a lesser evil in the whips’ eyes.

When a vote is called, the whips fan out to their positions, some lingering by the entrance to the division lobbies, others taking the opportunity to put one last arm around wavering backbenchers. A whip from the government and a whip from the opposition stand at the top of both the Aye and the No lobbies, counting MPs as they pass through to vote. After cross-referencing the numbers, the four tellers head to the Commons chamber to announce the result, the two from the victorious side standing on the right facing the Speaker’s chair.

With tired MPs prone to slinking off the parliamentary estate, whips also guard various portals in the Palace of Westminster. Walter Bromley-Davenport, a Conservative whip from 1948 to 1951, stood at one exit when he saw a man leaving before the vote at 10 p.m. Believing the person in question to be a Tory backbencher, Bromley-Davenport ordered him to stay, but the man refused, so he kicked him. Soon, the whip would be made aware that the person was not an MP but the Belgian ambassador. Fellow Conservative MP Ted Heath, who would regale future generations with this encounter, replaced him in the whips’ office.

Voting alongside members of the Cabinet and the Prime Minister offers a chance for MPs to raise issues or concerns with seniors. It also allows whips to look MPs in the whites of their eyes before they cast their votes. ‘It does have more of an impact than you just making a 10telephone call when they’re in the safety of their home,’ says an ex-Tory whip.

Like journalists curating sources, whips can draw on relationships in times of need. When a Tory backbencher told their whip, whom they’d known for several years, that they planned to vote against a motion put forward by the Liberal Democrat–Conservative coalition government, the whip replied: ‘Could you not just go home – for me?’

Out of deference to their friendship, the backbencher did just that.

The odd principled stand might not damage an MP’s career. British politics has seen its fair share of high achievers who have not abided by a three-line whip. Just ask David Cameron, Boris Johnson and George Osborne, who, in 2002, opted to abstain rather than vote against allowing unmarried and gay couples to adopt as ordered by the then Tory Party leader, Iain Duncan Smith.

What’s for certain is that repeat offenders aren’t likely to secure preferment of much quality, if at all. The ‘recalcitrants’ – MPs who can never be relied on to support the party line – whips largely leave alone.

Pivotal for The Office is avoiding an otherwise loyal MP becoming a persistent rebel. A few politicians have even shed tears after rebelling on an issue they couldn’t countenance supporting. But once the Rubicon is crossed, rebellions become easier, sometimes habitual.

A WHIP’S CORE

What sets whips apart from other Members of Parliament is that they take an effective vow of silence on joining The Office.

Government whips in the Commons do not speak from the despatch box or offer their views on policy in public, save for when they hold multiple roles or a minister commits what The Office considers to be a sin against the Holy Ghost and fails to turn up to the chamber.311In such a rare scenario, whips may have to take the minister’s place at the despatch box.

Even the slightest hint of a minister being missing-in-action gets the whips all hot and bothered. In the first parliament of the New Labour government, Helen Liddell told a senior whip she was going to rest in her office near the Commons before leading the adjournment debate at around 3 a.m. The minister couldn’t sleep, so she showered and returned to the chamber. With the previous debate nearing an end and the whips unable to locate Liddell in her office, they turned the building upside down looking for her. Hurrying back into the chamber with instructions for the minister speaking to buy more time, the whips saw Liddell in her place on the frontbench, sitting, as she recalls, ‘like a little angel’.

Whips still serve their constituents and can write in their local paper, but they must avoid being the subject of journalists’ interests; being caught up in controversy is a cardinal sin.

There are sixteen government whips, one of whom – usually the latest entry-level addition – doesn’t receive a ministerial salary on top of their pay as an MP. The junior rank is an Assistant Government Whip, followed by Lord Commissioners, before we get to the top four: the Vice-Chamberlain, Comptroller, Deputy Chief Whip (or Treasurer) and the Chief Whip.§

In modern times, though not always, the Comptroller oversees pairing, an informal arrangement between whips’ offices that allows parties to offset absentees. Back in the day, MPs from rival parties could agree to be each other’s pair, negotiating absences before running it past their respective whips’ offices. One person will also have the unenviable role of Accommodation Whip, fielding requests from disgruntled MPs for a better workspace.

After the 1997 general election, Tory whip Peter Ainsworth and 12Desmond Swayne, the MP for New Forest West, were surprised to find that the newcomer had been given a ‘perfectly acceptable’, albeit windowless, office on his arrival at Westminster.

‘Oh, there’s probably been a mistake,’ Ainsworth said. ‘Anyway, this is your room.’

The next day, Ainsworth paid Swayne a visit. ‘Desmond, there was a mistake. We need that room for [former Prime Minister] John Major’s staff. I’ve got a better one for you.’

Ainsworth took Swayne to a room on a higher floor that he remembers as being ‘literally a cupboard’.

‘You said this would be a better one?’ Swayne asked.

‘Well,’ Ainsworth replied, ‘it’s got a window.’

Whips speak fondly of being part of a team, of the comradeship born of a shared cynical humour, itself a byproduct of dealing with difficult MPs and the stresses of working at the heart of British politics. One person even acts as the Social Whip (or Entertainment Whip), arranging dinners and other opportunities to kick back after pulling all manner of parliamentary strings (whips of a certain vintage were also sent abroad on so-called Whips’ Trips, often to smaller countries ungraced by visits from British Foreign Office ministers). Though departmental ministers theoretically work together, often, they do so in competition or without much by way of collaboration. ‘In politics, the whips’ office is the only team you’ll ever work in,’ says a former Tory Deputy Chief.

The government and opposition parties also have a whips’ office in the House of Lords, responsible for managing (or responding to) the legislative programme in the upper chamber. With far fewer goodies or leverage to motivate their colleagues – who don’t face elections, whose ambitions have waned and attendance varies – whips in the Lords, known as baronesses or lords in waiting, draw on relationships to encourage peers to turn up and vote.

‘In the Commons, the whips pin you against the wall and tell you 13how you’re going to vote,’ jokes a Labour peer. ‘In the Lords, they come up and say, “Can I buy you a glass of wine?”’

A WHIP’S FLOCK

Each whip is assigned a ‘flock’, a group of people with whom they keep in regular contact, and whose attendance they are accountable for at key votes.¶ Depending on how many MPs or peers the party has, a whip will oversee up to thirty people in their flock.

Robert Hughes, a whip under John Major, resents the term ‘flock’, arguing that MPs are ‘not sheep’. His colleague in The Office Sydney Chapman was fond of advising new whips about MPs: ‘Not everybody needs to have their way, but everybody needs to have their say.’

Ahead of a three-line whip, Steve Bassam, then the Labour Chief Whip in the Lords, asked his team to provide an update on their flock. When one whip said they’d been trying to locate a peer for weeks, Bassam remarked: ‘Well, if you do get through to him, I’d really appreciate you letting me know. After all, he’s been dead for six months.’4

Whips are an essential two-way communication channel between the Prime Minister (or leader) and their MPs. They explain government policy to their flock, report MPs’ concerns to higher-ups and, if required, arrange meetings with ministers and other senior folk for further convincing or assuaging. They also provide guidance, support and an outlet for MPs under heavy strain.

Bring together hundreds of people at random and, at any one time, some will be experiencing illness, bereavement, marriage breakdowns, financial concerns, mental ill health or any other life-related detour, and it’s the whips’ job to monitor, regulate and look out for MPs under 14strain. As such, whips have a voracious appetite for, and are privy to, all manner of intelligence and information. They see, in the words of a Tory whip from the 1990s, ‘the underbelly of human life’, from dealing with the chancers who visit The Office to spread bile about their colleagues to identifying the lifeless bodies of MPs who have drunk themselves to death.

Each whip is also allocated one or more government departments, attending internal meetings with the relevant ministers and officials and helping to take legislation through its parliamentary stages. As part of this work, whips oversee committees that scrutinise bills in minute detail, ensuring their MPs turn up and, where possible, toe the line.

‘Part of the trick with bill committees|| was not putting rebellious MPs on them,’ says an ex-Tory whip, who didn’t want their friend, a fellow MP and expert on mesothelioma – a type of cancer – on a related committee ‘because I couldn’t guarantee she would support the government’. The ex-whip adds: ‘You end up doing these ridiculous things of not putting people who really know a load of stuff on a committee because you need to get it through.’

News of a defeat on Committee Corridor often reaches The Office before the whip returns to their desk. There, they’ll have to answer to higher-ups, not least one of the most feared political figures stalking the Palace of Westminster.

* For his deft handling of the Commons as party manager for the Whigs, some academics argue Thomas Pelham-Holles (1693–1768), the Duke of Newcastle and former Prime Minister, was the first whip.

† The line of a whip relates to attendance. In June 2025, ahead of a division on decriminalising abortion – an issue of conscience – the whips issued a three-line whip to attend but gave MPs a free vote.

‡ MPs can also vote in both division lobbies to register an abstention.

§ More on these roles and the source of their grandiose titles soon.

¶ Flocks were often divided by region, but modern whips’ offices have opted for more of a mix, ensuring the team shares MPs from different generations, political backgrounds and personality types. An effective whips’ team will also mirror its parliamentary party, with appointees from different ideological wings. This way, whips can gain access to different factions and understand the mood of backbenchers.

|| Bill committees were known as standing committees until 2006. MPs selected to serve on bill committees, in addition to their support of the party line, often represent different regions and viewpoints on the matter at hand.

Chapter 3

The Chief

Even for newcomers arriving in Westminster today, the Chief Whip – known within their parliamentary party as ‘Chief’ – is among the most revered individuals in British politics.

It’s not just thanks to Michael Dobbs’s House of Cards that the Chief has accrued a reputation for putting a bit of stick about. Often a brooding, aloof figure who sits above the fray, several stern disciplinarians (some prefer the phrase ‘quietly menacing’) have acted as Chief Whip, not least Conservative MP David Margesson, appointed to the role in late 1931.

Considered by many to be the quintessential Chief, Margesson was tasked with keeping together successive multi-party national governments, drawing on a firm, even-handed approach that historian Eliot Wilson characterised as ‘strict but not universally bullying’.1

For his part in a rebellion that helped bring down Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain in May 1940, Margesson wrote to John Profumo, a young Conservative MP, and said: ‘I can tell you this, you utterly contemptible little shit. On every morning that you wake up for the rest of your life you will be ashamed of what you did last night.’

With a nine-year tenure, Margesson remains the longest-serving Chief Whip in government.

The Chief, whose work is rarely seen by an untrained eye despite being felt across Parliament, is now issued a black folder inscribed with their job title. (Chiefs can, if they wish, also take home a black, rather than red, ministerial box.) A close confidant to the Prime Minister and 16MPs seeking counsel or a shoulder to cry on, the Chief, who attends Cabinet, has key legislative, parliamentary and disciplinary responsibilities. At their zenith, in addition to a ringside seat at government reshuffles, Chiefs had a significant say in awarding honours, positions on quangos and appointing peers.

‘We got a big map of the British Isles, put it on the floor, and we tried to allocate [honours] around the country,’ remembered Edward Short, Labour Chief Whip from 1964 to 1966.2 Short would send his list to the Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, who ‘nearly always’ took his recommendation.

This power is now centralised in No. 10, although, in theory, there remains the opportunity for input. Regardless of what they’ve lost, the Chief – also known as the Patronage Secretary – retains considerable goodies at their disposal.

A former Government Chief Whip explains:

Because the Chief plays a really important role in advising the Prime Minister on people issues, promotions and demotions, you are treated with a great deal of care by MPs. Rightly so. Not particularly because you deserve it, but because you can cause them problems. That will probably be ever thus.

No Chief would be effective without a team of officials behind them, led by a civil servant whose contribution to parliamentary life cannot be understated, despite often going unsaid.

THE USUAL CHANNELS

When it comes to setting the parliamentary agenda, the government holds the initiative. However, given the scale of business to get through, a degree of cross-party cooperation is required to agree on 17a sensible timetable for bills, debates and more. And yet, before 1919, there was no official mechanism for political parties to negotiate. That all changed with the arrival of the most important civil servant you’ve never heard of.

The role of principal private secretary (PrPS) to the Government Chief Whip* is multifaceted, influential and powerful. A report for the Hansard Society argued the PrPS and their office are ‘the sewers of the system’. ‘No one talks about them, but without them, the system would collapse.’3

The PrPS supports the Government Chief Whip in securing the government’s legislative programme, advises ministers and departments on procedures and bills, monitors proceedings in the Commons and runs a team of civil servants, including in the opposition whips’ office.

‘The holder needs to be totally across everything that’s happening in government and know everything there is to know about how laws are made,’ says a parliamentary expert who worked in the whips’ office.

Most eye-catching from our perspective, the PrPS acts as a pivotal interlocutor, helping to facilitate discussions in what’s known as the Usual Channels. A catch-all term for negotiations between the government and the opposition, the Usual Channels feature senior members of the whips’ office, the Leader of the Commons and equivalent opposition spokespeople. From weekly meetings on the upcoming business to daily talks over arrangements for pairing, the system ensures that neither side is blindsided, creating a ‘gentlemanly’ state of competition rather than war, says a former whips’ office adviser.

The Usual Channels can also pertain to backroom interactions between party leaders. Ian Blackford, the Scottish National Party’s leader in Westminster from 2017 to 2022, had a ‘straightforward’ relationship with Prime Minister Theresa May, whose team would let him know in advance if she planned to speak in the Commons the following 18Monday, so that he could return from his constituency of Ross, Skye and Lochaber in time to question her in Westminster. In March 2018, Blackford also received national security briefings in the aftermath of the Salisbury poisonings, which allowed him to prepare his party’s response.

With Boris Johnson, things were different. In the summer of 2021, according to Blackford, the then Prime Minister led a debate on reducing overseas aid from 0.7 per cent to 0.5 per cent of GDP without first informing opposition leaders, who would otherwise respond on their party’s behalf, that he was due to speak in the Commons. ‘The first time I knew that Boris Johnson was speaking was when I was watching the television in my office, and he was on his feet,’ Blackford says. In August 2021, as the UK withdrew its forces from Afghanistan, No. 10 initially offered just one question each for opposition leaders to ask the national security adviser ahead of a statement from the Prime Minister in the Commons.

Blackford would say to the Chief Whip Mark Spencer, with whom he got on well, ‘Look, Mark, this is just intolerable.’ Spencer, he says, ‘wouldn’t disagree’.

As an honest, nonpartisan and trusted broker, the PrPS straddles a fine line, working for the government while being available to opposition parties. ‘It requires unique skills. You have to maintain the confidence of two parties that are opposed to each other and negotiate,’ says an ex-Government Chief Whip. Another says their PrPS told them: ‘I work for you 51 per cent of the time and the other parties 49 per cent of the time.’

A fount of knowledge for whips across generations, PrPSs are known for their remarkable longevity. In more than a century, just a handful of people have served in the role. The first to hold the position, Charles Harris, retired in 1961, forty-two years after taking office. Earlier this decade, Victoria Warren became the first woman and fifth person overall to serve as PrPS to the Government Chief Whip. ‘From the 19most humdrum, “What are the travel arrangements for X?” to “What is the hold-up on this bit of a bill?”, she can pretty much find out anything within an hour,’ says a colleague of Warren’s.

As with other senior civil servants, the PrPS is chosen after an appointment process involving the Civil Service Commission, with the candidates also run past the Prime Minister. Outlasting whole governments, premierships and Whitehall departments, the PrPS is often called upon for all sorts of things outside their remit due to their expertise. ‘It is absolutely not an exaggeration to say that the PrPS is the single most plugged-in person in the whole of government,’ says a person who worked in The Office.

OFFICE BREAKDOWN

The whips have an office on Downing Street and another just off Parliament’s Members’ Lobby, a restored hallway damaged during the Blitz which separates the Commons chamber and Central Lobby. Guarded by fading statues and busts of British political titans, Members’ Lobby also houses the opposition whips’ office, now occupied by the Conservative Party.

The government whips’ office in Parliament, taken up by the Labour Party, is split between an upper and lower section, with the latter down a short flight of stairs. Though traditionally this arrangement reflected The Office hierarchy, with desk space assigned on seniority, Sir Keir Starmer’s government opted to seat junior members of the team with senior whips in the upper office, evoking the configuration used the last time the party was in power. Lord Commissioners take up the lower office.

The Chief Whip’s parliamentary workspace is accessed through the upper office. The scene of tense conversations about the future of Prime Ministers, its meagre size belies its role in British political 20history. Inside, above a door that’s no longer used, is a ticker tape that harnessed the same technology as those seen on stock exchanges from the late nineteenth century, which, when functioning, would reveal things like who was speaking in the Commons.

We often think of the whips’ office as one entity, but it has different components, consisting of civil servants and aides who help support the whips in carrying out their duties.

The Government Chief Whip’s Office (GCWO) came into force with the creation of the PrPS. The Cabinet Office administers the GCWO, but it essentially runs as a small government department. It includes the PrPS, a de facto deputy PrPS and other private secretaries, from legislative experts to those who manage diaries and other key administrative tasks.

Chief Whips today appoint up to three special advisers (SpAds), who work closely with whips, MPs, departments and civil servants.† From managing spreadsheets of MPs’ voting intentions to writing questions for whips to ask their flock, SpAds have only increased in importance. They also get involved with some of The Office’s cunning ploys.

In late 2020, Boris Johnson’s government leaked like a sieve. ‘You need to do something about this,’ a senior No. 10 staffer told Mark Spencer, the Chief Whip. Suspecting that the leaks to the media were coming from one of the MPs serving as a ministerial aide, his SpAds devised a ruse. A letter was sent to each of the MPs reminding them that they were subject to the ministerial code and, therefore, couldn’t leak government business. The SpAds made very slight adjustments to each correspondence sent out in the Chief’s name, tweaking an ‘and’ here or an ‘of’ there. Soon, one of the letters emerged on the political website Guido Fawkes. The aides studied their lists and cross-referenced the 21letter with those they’d distributed. Tory MP Andrew Lewer, a ministerial aide in the Home Office, lost his job.

‘In nearly twenty years of elected office, I have never leaked to the press,’ he told POLITICO. He also suggested the leak might have come from a member of staff.

The GCWO sits adjacent to the Government Whips’ Admin Unit (GWAU), which oversees the whips’ office’s activities, from working with the Pairing Whip on MPs’ absences to ensuring committees and debates are attended.

Among the legislative wonks in the whips’ office is a ‘fixer’ who undertakes assignments such as solving computer issues and distributing papers. A former colleague explains: ‘You tell him this is the mission, this is what we need from the mission, and he’ll make it happen.’

THE DAY-TO-DAY

For SpAds, the day begins around 6.30 a.m. with a strong coffee and BBC Radio 4’s Today programme. Perusing the newspapers, they try to consume as much information as possible before leaving their homes, reading the order paper while on the Tube to Westminster.

At 8 a.m., they attend a twenty-minute meeting of the Chief Whip’s office on Downing Street. Civil servants, led by the PrPS, first run through the business in the Commons and any items the Chief should know. The SpAds will then discuss political issues, such as an MP overnight writing an article critical of the government – an act viewed by The Office as a transgression – and what to do about it. Only if the matter is ‘dicey’ will the (politically neutral) civil servants be asked to leave the meeting, says a person in the room.

The briefing prepares the Chief Whip for the daily 8.30 a.m. meeting in No. 10, where he updates the Prime Minister on any potential stumbling blocks in Parliament or political noise that he should be aware 22of. The Chief and the PM also speak one-on-one before a meeting of the Cabinet at 9.30 on Tuesday mornings. Whenever the Prime Minister addresses the Commons, the Chief Whip will be in or around the chamber, sitting next to the gangway. An insider says the relationship between the whips’ office and No. 10 is essential in keeping the government across the sentiment in Parliament. ‘It’s half a mile away, but it might as well be 100 miles away sometimes in terms of where the focus is,’ they say of 10 Downing Street.

Fifteen to thirty minutes before the House sits, government whips gather in the upper office for a meeting chaired by the Deputy Chief Whip, who acts as first mate, overseeing the running of The Office while the captain – the Chief – plots the route. The whips account for their flocks if there’s a big vote ahead. Otherwise, the Deputy will run through the order paper, appoint tellers and reflect instructions prepared by the GWAU for the person on bench duty to follow.‡ The Chief will provide an update should they have one. On Wednesdays from 9 a.m., the whips and SpAds gather at their Downing Street abode for a longer meeting to discuss departments, flocks and the business.

‘The main job of the whips is to make sure that business begins on time, business finishes on time, and in between, it runs as smoothly as possible,’ says former Tory whip Liam Fox. ‘It’s the essential lubricant of Parliament. It is the oil that keeps the gears of Parliament running.’

THE OTHER VIEW

Not everyone sees The Office in a positive light.

In 2010, then Tory MP Peter Bone proposed a bill to effectively outlaw whips, arguing that Parliament needed its teeth back. Another critic is Douglas Carswell, a former Tory MP who defected to UKIP 23in 2014. ‘If you wonder why we govern 60 million people and yet the people who get to the top of politics are so dreadful, they always screen out talent,’ he argues. ‘[Whips] encourage obsequiousness, they encourage mediocrity. People sometimes describe them as Machiavellian – Machiavelli had a philosophy and a competence… These people couldn’t run a bath. They’re appallingly incompetent.’

Advocates say that, far from being undemocratic – an occasional charge among critics – whips help ensure that the British people’s will is enforced through implementing election manifesto pledges. ‘You cannot run a programme of government, with all the moving parts that that requires, without a whipping operation,’ says a parliamentary expert who worked in the whips’ office.

Some also stress that MPs owe a degree of loyalty to their party and leader. A Cabinet minister under Margaret Thatcher recalled the Prime Minister following a backbencher, who had narrowly won at a by-election, out of the chamber after swearing in as an MP. The man thanked her for coming up to his constituency during the campaign and said she had earned him the last votes he needed to secure victory. Thatcher looked at the MP and said: ‘No, no, no. You’ve got it entirely wrong. You won the 150 votes. I got you the other 25,000.’

The Thatcher-era minister adds: ‘In a sense, it’s absolutely true. The individual candidate makes a difference at the margins. The popularity or success of the Prime Minister is what wins or loses the actual election itself.’

Though the Chief is the most senior in The Office, three government whips have duties that, now and then, take them away from Parliament to the other key component of Britain’s constitutional monarchy. 24

* Not to be confused with MPs who serve as aides to government ministers, known as parliamentary private secretaries.

† Whips and SpAds, for example, collaborate with departments to develop the strategy for a government bill, including potential concessions and engagement plans. SpAds also confer with their equivalents in the Lords to understand views on the red benches and where peers might push back. (MPs seeking to amend legislation often coordinate with like-minded peers who can return a bill to the Commons with proposed changes.)

‡ Whips rotate responsibility for sitting on the frontbench in the chamber. More on this in later pages.

Chapter 4

A Royal Office

The whips’ office, not unlike the country, can pivot to moments of great pageantry at the flick of a ceremonial white stave.

The Office’s second, third and fourth in command – known respectively as the Treasurer, Comptroller and Vice-Chamberlain – are part of the royal household, an organisation that supports members of the royal family. Appointed by the Prime Minister rather than the sovereign, the roles, which long predate the creation of The Office as we know it today, have coalesced over time around these three senior whips, having been held for centuries by a mixture of courtiers, noblemen, Members of Parliament and peers in the House of Lords.*

Tasked with duties of historical significance, these whips play a symbolic role in Britain’s constitutional monarchy, where the sovereign is head of state but the elected Parliament makes and passes laws. From being held hostage to securing the monarch’s signature, whips help bridge the mile-long stretch between the Palace of Westminster and Buckingham Palace.

WANDS, PARTIES AND BUTTERFLIES

Stage-managed between ever-grander rooms by Palace officials while 26waiting for an audience with the sovereign at Buckingham Palace, each royal whip receives a ceremonial white stave on appointment.

‘The Palace know how to make you appreciate every moment of it,’ says a former whip, who received their white stave from Queen Elizabeth II. ‘You feel that you are physically getting closer and closer to the Queen. I can tell you it does cause the butterflies to start fluttering.’

The ‘wand of office’, which unscrews into two parts, symbolises its holder’s prestigious position as an officer of the royal household. Whips used to keep their staves free of charge after leaving their post before successive leaders installed a revolving door in The Office.

‘It’s just a bit too expensive [for the Palace] to keep giving these things away,’ the former whip explains. Another says they considered buying the stave – which they priced at ‘about a thousand quid’ – but thought it would collect dust in their umbrella stand.

In addition to greater responsibility in The Office at Westminster, the three senior whips perform several royal-adjacent functions, including attending garden parties at Buckingham Palace dressed in morning suits or formal daywear, staves in hand. With support from royal equerries,† they introduce the monarch and other senior royals to assembled guests.

During her events – she attended nine – Anne Milton, a former Tory Deputy Chief Whip, followed Queen Elizabeth II around the Buckingham Palace grounds. ‘Your feet are aching, and you look at this woman who’s thirty, forty years older than you, and think, “My God, how is she still going?”’ With no prior warning about wearing stiletto heels, Milton spent most of her first garden party trying not to sink into the grass across from the royal tea tent.

On another occasion, she stood before ‘quite a small man’ when Prince Charles entered the marquee.

27‘Oh, I’m so sorry. I’m standing in your sight line,’ Milton said to the man.

‘No, no,’ he replied. ‘Stay exactly where you are.’

‘Don’t you want to see?’

‘I do not want to be seen,’ the man said. ‘I am the head of the Supreme Court, and I’ve just agreed that Prince Charles’s private correspondence should go into the public domain.’‡

THE KING’S SPEECH

Outside of garden parties, diplomatic receptions and rarer occasions like a coronation or funeral, the three royal whips also gather for the state opening of Parliament. Here, they are involved in a ceremonial act that captures the constitutional function of the royal whips.

Known as the King or Queen’s Speech, the state opening represents the formal commencement of the parliamentary year, during which the monarch sets out the government’s legislative agenda on its behalf. Before proceedings begin, the Treasurer and Comptroller accompany the Vice-Chamberlain to Buckingham Palace, where they enjoy coffee and a tour of the crown jewels and wave off the royal party en route for Westminster.

In a practice dating back to the reign of Charles I, the last king to enter the House of Commons who had a contentious relationship with Parliament, the Vice-Chamberlain is then left with the Lord Chamberlain, the most senior officer of the royal household, who keeps them ‘hostage’ until the monarch’s safe return.

With the royal party on the way and the Vice-Chamberlain in safe hands, the Treasurer and Comptroller head back to Parliament in a horse-drawn carriage supplied by the monarch.

28Travelling down the Mall, Milton heard calls of ‘Anne!’ from the crowds. ‘Gosh, how do they know it’s me?’ she thought, forgetting about the Queen’s only daughter by the same name.

Back at Buckingham Palace, the Vice-Chamberlain prepares to watch the state opening on a television in a small drawing room.

A former senior Buckingham Palace official says that when offered a beverage, the Vice-Chamberlain ‘sometimes wanted a stronger drink than a cup of coffee!’ Sir Desmond Swayne, Vice-Chamberlain from 2013 to 2014, recalls an equerry asking whether they should open a bottle of sherry or champagne. ‘Well, let’s have both!’ he replied. Later in the day, the Queen hosted a drinks reception in an equerry’s office to thank those who had helped with the event, serving ‘very stiff’ gin and tonics. ‘You’re crammed almost like a sardine up to the Duke of Edinburgh and chatting away and all the rest, knocking back the gin. It was a frightfully enjoyable excursion,’ Swayne says.

During his first state opening in late 2019, an equerry offered then Vice-Chamberlain Stuart Andrew a hot drink before saying, ‘You look like you’d like something a bit stronger!’ and returning with a bottle of champagne. Andrew was ‘a bit swiffy’ when the Queen arrived back at Buckingham Palace.

At his next state opening, the Queen turned to him at the bottom of the stairs and said: ‘You have a good time again, won’t you?’

THE MESSAGE

Insofar as royal responsibilities are concerned, which are secondary to the whips’ primary focus of securing the government’s business, one person carries the largest burden.

The Vice-Chamberlain writes a report for the monarch on events in the Commons every day it sits, except on Fridays. The process involves 29a degree of choreography: the Government Whips’ Admin Unit puts together a draft featuring some of the salient moments of the day and passes it to the Vice-Chamberlain. The Vice-Chamberlain then makes changes, additions, flourishes or rewrites before it’s given a final scan and sent to Buckingham Palace.

The report, known as the ‘Message’ and now sent via email, keeps the monarch abreast of their government’s activities in the Commons. Usually around 600–800 words, in old money it was one or two sides of A4 paper, which a State Messenger would deliver to the Palace at 6 p.m. The letters are headed with the Vice-Chamberlain’s name, followed by ‘with humble duty reports’ and the greeting to ‘Your Majesty’.1

In January 2025, the King hosted a reception at Buckingham Palace for MPs first elected at the previous year’s general election. The whips’ office suspected there might be votes in the Commons that day, so they managed the business to ensure that any divisions would take place later in the afternoon, allowing the cohort of more than 200 new Labour MPs to return from the reception. Labour minister Nic Dakin, wrapping up the second reading debate on the Arbitration Bill, gave what an eyewitness describes as one of the most boring parliamentary speeches in recent memory to buy the whips more time.

‘I will, if I may, indulge in sharing some of the supportive quotes from the sector…’ Dakin said at one point, to which Conservative frontbencher Dr Kieran Mullan, apparently desperate for the laborious speech to end, shouted from his seat: ‘No!’

A person in the Labour whips’ office says the King was amused to read of the filibuster in the Message from Vice-Chamberlain Samantha Dixon later that day.

Some Vice-Chamberlains have underestimated the report’s importance to its recipient. During Mark Spencer’s tenure in 2018, an IT issue meant the Message didn’t reach the Queen for two days. The Palace wrote to ask: ‘Where are the updates?’ 30

‘It came as a bit of a shock that she was actually reading them,’ Spencer says. ‘Then you’re thinking, “Shit, I’ve got to get this right.”’

Vice-Chamberlains vary in their approach and how much they contribute to the Message. In his pre-political life, Donald Coleman, Vice-Chamberlain from 1978 to 1979, used to have a weekly column in a national newspaper. ‘You can say that my daily message to the Queen … is not unlike what I used to write for The Guardian,’ he said.2 Spencer Le Marchant, a colourful whip and racehorse owner, would slip racing tips into his report. ‘His summary was particularly appreciated at Buckingham Palace,’ wrote a fellow Conservative.3

When Labour’s Jim Fitzpatrick met the Queen for the first time as Vice-Chamberlain in 2003, he asked what she would like to read. ‘Her answer was something along the lines of, “That which doesn’t reach the papers is always very interesting,”’ he recalls. ‘In other words, give me the gossip; give me what’s not fit to print.’

Richard Luce, an ex-Tory whip who served as Lord Chamberlain from 2000 to 2006, confirms: ‘The fact is that the Queen enjoyed receiving these daily reports, but only if they were – I’m exaggerating slightly – spicy!’ Luce once asked the Queen if she would like a similar readthrough of events in the House of Lords. ‘Certainly not!’ she replied.

Luce explains: ‘She didn’t really want any more reports, but she enjoyed the liveliness of the Commons and just knowing a bit about the personal side, not about the dreary side of what one said in the debate, because all that’s recorded in Hansard.’

The Queen would raise details and observations in Vice-Chamberlains’ reports during private audiences at Buckingham Palace, which take place every few months. After the 2019 general election, Stuart Andrew reflected in a letter on the ‘ambitious’ new intake of Conservative MPs. A few months later, the Queen asked in person if the new intake was ‘still as ambitious’. 31

Before his first audience with the Queen, officials told Desmond Swayne that he should refer to her initially as ‘Your Majesty’ and then as ‘ma’am’. At the end of the briefing, a courtier told him that on no account was he to follow the tradition of walking backwards on taking his leave. ‘We’ve abandoned that,’ they said.

With the meeting over, the Queen asked Swayne, a well-turned-out and eccentric MP, if he planned to walk backwards.

‘Well, I was told not to,’ he said. ‘Do you want me to?’

‘It’s entirely up to you. You just struck me as a man who likes traditions, but this is entirely up to you.’

‘Well, if it’s all the same with you, ma’am, I will walk backwards.’

‘Oh, for heaven’s sake make sure you don’t trip up,’ the Queen said, ‘or I’ll be in terrible trouble with the suits!’

HUMBLE WHIPS

As part of their constitutional role, the Vice-Chamberlain must also take to Buckingham Palace a ‘humble address’ – a communication from Parliament to the sovereign – for the monarch to sign.