8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Swift Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

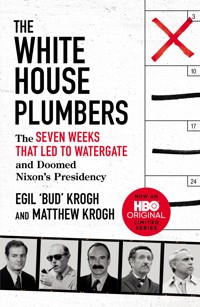

SOON TO BE A FIVE-PART HBO SERIES, STARRING WOODY HARRELSON AND JUSTIN THEROUX The true story of the White House Plumbers, a secret unit inside Nixon's White House, their ill-conceived plans to stop the leaking of the Pentagon Papers, and how they led to Watergate and the President's demise. On July 17, 1971, Egil "Bud" Krogh was summoned to a closed-door meeting by his mentor – and a key confidant of the president – John Ehrlichman. Expecting to discuss the most recent drug control program launched in Vietnam, Krogh was shocked when Ehrlichman handed him a file and the responsibility for the Special Investigations Unit, or SIU, later to be notoriously known as "The Plumbers." The Plumbers' work, according to Nixon, was critical to national security: they were to investigate the leaks of top secret government documents, including the Pentagon Papers, to the press. The White House Plumbers is Krogh's account of what really happened behind the closed doors of the Nixon White House, how a good man can make bad decisions, and the redemptive power of integrity. Including the story of how Krogh served time and later rebuilt his life, The White House Plumbers is gripping, thoughtful, and a cautionary tale of placing loyalty over principle.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 204

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

SWIFT PRESS

First published in the United States of America by St. Martin’s Publishing Group 2022

First published in Great Britain by Swift Press 2022

Copyright © Matthew Krogh 2022

The right of Matthew Krogh to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

A version of this book, titled Integrity: Good People, Bad Choices, and Life Lessons from the White House, was published in 2007 in the United States of America by PublicAffairs, a member of the Perseus Book Group

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 9781800752009

eISBN: 9781800752016

To Egil “Bud” Krogh, whose greatest wish was for each of us to have the integrity to make the next right choice (August 3, 1939–January 18, 2020)

CONTENTS

Preface

Prologue

1. Two Decisions in Two Days

2. The Plumbers Gather in Room 16

3. A New Leak for the Plumbers

4. Sparring with the CIA, FBI, and “Deep Throat”

5. A Proposal Gone Awry

6. Blind Loyalty Ensnares Me in Watergate

7. Pleading Guilty

8. From Courthouse to Jailhouse

9. The Road Home

10. Making Amends, and a Final Parting

11. Closure

Timeline

Oath of Office (1966, PL 89–554)

Letter of Resignation

Statement of Egil Krogh, Jr., to the Court

Acknowledgments

PREFACE

In my dining room at home in Bellingham, Washington, I still have the brown leather recliner that Dad bought so he could be more comfortable while we worked on this book together. It’s faded from the sun and slightly crackly, much like the older recliner my brother Peter still has, one that Dad brought back to Washington State from our time in Washington, D.C. Dad passed in January 2020, and atonement for his impact on America, on the executive branch, on the rest of us, was a core theme of his life since getting out of prison in 1974.

Dad was an animated and compelling storyteller, and a person who thought deeply about his moral compass and the implications of choices he had made. In 2006, when we started this book in earnest after successfully finding a publisher with our wildly talented agent (and, full disclosure, Bud’s stepdaughter and my stepsister Laura Dail), the theme was different than it is now. Then, the theme was more focused on personal atonement.

But as the book took shape, the key question of why one might end up searching for atonement became the focus. The answer: a loss of integrity. In a 1974 article in Redbook by my mom, Suzanne, she recounts our family’s experiences during the Watergate period and her frequently confirmed first impression of Dad as “a highly intelligent man with a wry sense of humor and, most important, as a man of integrity.” Dad had all kinds of metaphors for integrity—the hull of a boat, the shell of an egg, others more far-flung. But he spent years, decades, trying to understand why his own integrity was breached and eventually understood the long and painful process required to patch the hull of a boat that feels like it may never float again.

From meeting President Nixon in the Oval Office to his reinstatement to the bar ten years later, when he regained the privilege of practicing law after the most public of all scandals, Dad lived a journey that would be unlikely for anybody. But the lessons of what happened, how someone so driven by their own sense of right could go so wrong, feel universal. For Dad, both bookends were beginnings: The first beginning, the first bookend, was his meeting with Nixon to begin public life, a time when he took his own integrity for granted. After ten years, and the second bookend, he had a new beginning when he knew he could never again take his own integrity for granted.

Much of this book was written in a small office in my garage, as we talked through which aspects of his story made the most sense to include and, especially, which components contributed most to the core lesson about protecting one’s own personal integrity from sometimes overwhelming forces. After Dad’s passing, as HBO considered the possibility of basing a production on this work, Laura and I did more research into historical details to add. Some of the expanded story comes from Dad’s perspective, using contemporaneous quotes and notes from our conversations; other details are mined from memories of family members.

I don’t think as a child I had any real understanding of the magnitude of Watergate, or of Dad’s role and his public exposure. Even during the writing of the book, as we researched details to make sure we got them right, as we discussed what happened with Daniel Ellsberg, I still didn’t quite feel the importance. But as we did additional research in recent years, letters to the editor during Dad’s various reinstatement hearings surfaced. The passion that people expressed in print in the late 1970s—much negative, a lot positive—make some of today’s internet comments sections look tame by comparison. Those letters really shaped my sense of the personal impact that Dad and the Watergate scandals had on so many people at the time.

What you are about to read is a compact story, almost exclusively told through one man’s lens. Within every chapter, if you’re looking, you’ll find familiar stories and plot twists that you see in other, parallel narratives. The larger stories of Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers, Watergate, the CIA, U.S.-Cuban relations, the towering personality of Nixon—these are sprawling and immense. But I—we, including Dad—hope that this one focused perspective can shed some light on decision-making gone awry under high pressure and in secret, as well as explain one facet of the scandals that brought down the Nixon presidency.

Matthew Krogh, 2022

PROLOGUE

I first met President Richard Nixon in February 1971 in the Oval Office, when John Ehrlichman brought me in to meet my new boss. I last saw Nixon in 1976 in San Clemente more than six years later, after a series of scandals gripped the nation; after he won a wildly successful presidential reelection; after his subsequent resignation from the office of the presidency; and after a deep shift in Americans’ faith in the executive branch of the U.S. government.

I have held myself to blame, in part, for creating the conditions for the downfall of Nixon’s presidency. There were other players to be sure, many motivated by upright ideals, others less so, who were prosecuted and convicted for interrelated parts of the package of scandals that came to be known as Watergate. It remains the case, however, that during seven weeks of secret work in 1971, my group and I undermined the foundations of Nixon’s presidency. We went too far in our pursuit of what we believed to be critically important breaches of national security. And in time, we would pay.

At that time in 1971, David Young and I were codirecting the “Plumbers,” a secret White House group more formally known as the Special Investigations Unit, or SIU. The president had tasked us with stopping leaks of top secret information related to the Vietnam War, the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT I), and other sensitive foreign policy operations. We believed then that these leaks constituted a national security crisis and needed to be plugged at all costs. But we were wrong, and the price paid by the country was too high.

For years I pondered the reasons I committed a serious crime as codirector of the Plumbers. Our seven-week investigation targeted what we believed to be a serious national security threat—Dr. Daniel Ellsberg’s leak of the top secret Pentagon Papers to The New York Times—and culminated in the break-in of the office of his psychiatrist, Dr. Lewis Fielding. This crime and several others that followed, including the Watergate break-in and the illegal efforts to cover it up, eventually doomed the Nixon presidency. The break-in and burglary of Dr. Fielding’s office was the seminal event in the chain of events that led to Nixon’s resignation on August 8, 1974.

Those seven weeks during the summer of 1971 that doomed the Nixon presidency were not the only cause of that political tragedy. However, the burglary set a precedent that two members of the Plumbers could rely on when planning and executing the Watergate break-in in 1972. They knew that under certain circumstances, the White House staff would tolerate an illegal act to obtain information. Later, during the intensive Watergate investigations, one of the major reasons for the cover-up by President Nixon and former members of his staff was to prevent investigators from discovering information about the 1971 crime.

Extreme illegal acts were undertaken to prevent this discovery, including perjury, obstruction of justice, and the payment of hush money to the perpetrators of the 1971 crime to keep them from revealing it during the Watergate investigation. Several members of Nixon’s top staff feared that discovery of the 1971 events would imperil them and the president himself. Former attorney general John Mitchell, when apprised in 1972 of what had happened in 1971, accurately described the 1971 events as the White House “horrors.”

During the early years of the Nixon presidency, there was serious and lengthy discussion about using illegal means to get national security information from American citizens. On several occasions, wiretaps were placed without warrants. But the burglary of Dr. Fielding’s office constituted the most extreme and unconstitutional covert action taken to that date, setting the stage for the downfall of the Nixon presidency. Once undertaken, it was an action that could not be undone or explained away.

Why did this burglary happen? I am convinced, after reading dozens of accounts by others about those times and having long conversations with friends and former colleagues, that a collapse of integrity among those of us who conspired, ordered, and carried out this action was the principal cause. We made our decisions in an emergency context. The nation faced serious foreign policy threats from the Vietnam War and the Soviet Union, while the White House staff struggled with President Nixon’s penchant for secrecy, his fury at those who leaked classified documents, and his orders to investigate relentlessly those individuals he felt would compromise national security.

In 1971, I firmly believed that the information we hoped to acquire from Dr. Fielding would help us prevent further leaks from undermining President Nixon’s plan for ending the Vietnam War. Two and a half years later, I went to prison for approving and organizing that burglary. By then I was deeply remorseful, conflicted, and convinced that I had lost my way, a complete contrast to the ebullient good humor with which I had embarked on my great adventure in government.

Every administration brings in a huge cadre of younger staffers to fill the many crucial positions that keep the White House running. Those of us who joined the Nixon transition team to serve on Ehrlichman’s and H. R. “Bob” Haldeman’s staffs had no experience with high government. For the most part, we were young businessmen and lawyers who served on the 1968 campaign staff as advance men, policy analysts, speechwriters, or media experts and who were linked professionally and personally in some way with our principals before joining the staff. Our loyalties were to our principals and to the president personally.

Long before I understood the seriousness of the many responsibilities I would be given, I was sent to New York City to work in the transition office. The Nixon transition set up shop in the Pierre hotel in New York City, one of the most elegant and expensive hotels in North America. As the Pierre was located a block away from Nixon’s apartment on Fifth Avenue, the president-elect could walk to work each morning, providing numerous photo opportunities for tourists and journalists. Some of us who joined the transition staff in New York were lodged at the Wyndham Hotel, an actors’ hotel, located across 57th Street from the Plaza Hotel. Like the Pierre, the Plaza was a grand place with great tradition and astronomical prices. The most famous resident of the Wyndham during the two months I lived there was the prop dog who played in the hit musical Annie. Like two-legged stars, this dog had a staff of handlers who tried to keep him on leash and on schedule.

I shared an office on the eleventh floor of the Pierre with Edward Morgan, an Arizona lawyer, who had also been one of Ehrlichman’s most effective advance men during the campaign. When I first met Ed, he regaled me with stories from the campaign that made me feel I had missed out on one of life’s great opportunities. He was a very tall, heavyset man with a bright, cherubic face. When describing the day-to-day absurdities of the campaign and local political leaders, he would explode into long riffs of increasingly off-color language that left me and anyone else within earshot helpless with laughter. He became one of my best friends over the next four years.

Ed and I were tasked to vet the stock holdings and corporate backgrounds of the president’s nominees to the cabinet and sub-cabinet to make sure there were no real or apparent conflicts of interest. A federal statute prohibited an individual from holding a federal position that would enable him to benefit from that position. Not only were actual conflicts proscribed, but the appearance of conflicts was also outlawed.

One of the first sets of stocks and previous corporate responsibilities we reviewed involved the then governor of Massachusetts, John Volpe. The president had nominated the governor to be secretary of transportation. When he came to meet Ed and me, we discovered that there was a clear appearance of a conflict of interest because his privately owned company, the John Volpe Construction Company, was constructing the new Department of Transportation building in the capital. I told him we had learned there was a big sign out in front of the construction site that read, THIS BUILDING IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY THE JOHN VOLPE CONSTRUCTION COMPANY, or words to that effect. This constituted an appearance of a conflict, and we suggested that he change the name and convey all management responsibility to someone else. He agreed to do so. The governor and his lawyer returned a few days later to report on the steps they had taken. The governor said he had transferred all management tasks to his brother. We reviewed the document that showed his brother was directed under this shift in management to have no contact with the governor during his time of service at the Department of Transportation.

“That’s great,” I remember saying. “That should take care of the management issue. And what’s the new name?”

“I’ve changed it to ‘The Volpe Construction Company,’” he answered.

I looked at Ed, who was looking pensively at his desk. The mirthful twitching of his mouth indicated that he did not trust himself to respond.

I jumped in, trying my best to maintain a serious professional demeanor. “Well,” I said, “we’re getting closer. But I think the real problem, Governor, is not the first name, but the last. Perhaps you could find a name that doesn’t have ‘Volpe’ in it.”

He agreed and told his lawyer to come up with some suggestions. After concluding our financial discussion, the governor and his lawyer got up, we all shook hands, and then they left.

Our room at the Pierre was large and had been stripped of the bed and easy chairs. Ed and I faced each other while we worked, crammed in behind two large desks. Small chairs faced the sides of our desks, where the cabinet nominees and their lawyers sat while we worked through their financial histories. Three doors led from the room: one that led into the hall, one into the closet, and one into the bedroom. After winding up our vetting session with one cabinet-position nominee, who shall remain nameless, Ed and I turned around and moved over to sit down at our desks. We sensed the nominee turn around and, without hesitation, walk confidently into the closet, closing the door behind him. Ed and I looked at each other briefly, picked up some papers, and pretended to read through them. Had the man emerged immediately there wouldn’t have been a problem. But he delayed, excruciatingly.

Time stretched out as slowly as I can ever remember. A quick glance showed that Ed’s face was becoming redder and redder. I felt my eyes begin to water, and to keep from letting any weird sounds come out, I started biting the inside of my mouth. Finally—it seemed forever—we noticed out of our peripheral vision the knob on the closet door begin to turn ever so slowly. Then, as we continued to look at our papers and not toward the nominee, he slowly exited through the closet door and oozed along the wall to the other door, opened it gently, and tiptoed into the hall.

Ed exploded. He started laughing and sobbing so hard I thought he would choke. His head dropped down to his arms folded on his desk. My eyes were drowning in tears. I leaned back so far in my chair that I fell off onto the floor, where I sat gently banging my head against the wall. The high farce completely wiped out any prospect of further work that day.

“Twenty-seven fucking seconds,” Ed managed. “That’s how long he was in there.”

To let loose our pent-up hilarity, we rushed out of the Pierre that afternoon, took a left turn, and for the next two hours walked up and down Fifth Avenue singing Broadway musical tunes. We belted out songs from Oklahoma!, The King and I, Showboat, and whatever else came into our crazed minds. Christmas shoppers scurrying along Fifth must have concluded that we had started drinking hours earlier. We were part of the new government of the most powerful nation on earth, and it felt like the beginning of an exuberant journey in which we were all destined to ride high.

Four years later, the transformation could hardly have been more complete. The laughter lasted barely into 1969, and in its place a very different mood took hold. The mood was darker, less open, more anxious, more defensive. I was never again to be so happy-go-lucky in government as that afternoon at the Pierre allowed me to be.

EACH OF THE commissions that I was given during my time in the White House came with a handsomely framed certificate that included the phrase “reposing special trust in your integrity.” At the time, I thought nothing of the terminology; it seemed like governmental jargon, a way to make the process of taking a job more august. But in the years since, I came back to the language of those commissions and found in it a more subtle and far-reaching moral imperative. I skipped across it as a young man; later, I came to believe that integrity is one of the most important personal qualities that any individual in a position of power or responsibility can show, whether in business, politics, or public and private life. Trying to understand what integrity really means in those commissions helped me develop a framework for my own life and gave me a way of seeing how others in the pressure of competitive environments could avoid doing what I did. Because if you compromise your integrity, you allow a little piece of your soul to slip through your hands. Integrity, like trust, is all too easy to lose, all too difficult to restore.

Few who knew me in 1970 would have considered me as the sort of person who would break a law for any reason whatsoever. Raised in a highly moral family, provided with an excellent education including law school and the Navy, my values were those of Christian Middle America. Money, outside influences, the system itself can all be sources of the sort of corruption that infects politics. The same can be said for elements of the business world or any other competitive environment. I am now not the same man that I was as a twenty-nine-year-old, fresh-faced young man in government with the whole world apparently ahead of him. Sometimes I hardly recognize that younger man. It makes it easier to see his actions and decisions, for better or worse, in some kind of perspective. The young Bud Krogh wanted to do the right thing, but the correct path wasn’t always clear to him. A combination of youthful naivete, ambition, loyalty, and a military sense of duty—each a virtue in the right proportion—was his undoing when mixed with the rarer elements of a career in the White House against the fever-pitched backdrop of the Vietnam War.

My friend Lynn Sutcliffe wrote the following to the judge before I was sentenced to prison in 1974:

In most situations Bud’s commendable character traits would have caused him to disapprove the commission of an illegal act. The events surrounding the Fielding break-in played upon those usually commendable traits in such a way as to produce the opposite result. But to understand Bud’s actions is not to excuse or condone them.

By describing the circumstances around what happened in 1971, and the tumultuous events in American society at the time, I certainly don’t mean to excuse or condone my actions. I still deeply regret my actions, which worked a destructive force upon our nation. These actions and the efforts to cover them up led to widespread distrust in our government and its leaders that continues to this day. I do, however, mean to provide a partial explanation of how somebody like myself—somebody with all the advantages, somebody meaning to do well—can commit a crime not by accident, mind you, but by skewed priorities, misplaced loyalties, overwhelming external pressures, and clouded judgment.

During my time in the White House, there were many temptations or ideas that could have waylaid any of us. Ideologies, alliances, power, the ability to do good for the country and the world, all combined into a nearly intoxicating work and life environment. This story starts with a decision in the high summer of 1971, the consequences of which were quite different than any of us had foreseen.

1

TWO DECISIONS IN TWO DAYS

On July 15 and 17, 1971, President Richard M. Nixon made two critical national security decisions. The first decision will go down in the history books as one of the boldest acts of diplomacy in the twentieth century. The second decision, which embroiled me in more personal difficulties than I could ever have imagined, led to the downfall of the Nixon presidency.

I had been at an impromptu visit by Nixon to the Lincoln Memorial at 4:45 a.m. on May 9, 1970, a few days after he had decided to invade Cambodia. During an hour-long discussion with a group of stunned students who had come to protest his actions, he told them he had “great hopes that during my administration . . . the great mainland of China would be opened up so that we could know the 700 million people who live in China, who are one of the most remarkable people on earth.” That foreshadowing of his intention to open China finally climaxed with his electrifying announcement to the world on July 15, 1971.

On the evening of that day, the president told the world that on July 1, Dr. Henry Kissinger had conducted secret talks with Premier Zhou Enlai of China, during which Zhou invited Nixon to visit China “before May 1972.” The president said he had accepted Zhou’s invitation with pleasure. His subsequent visit to China in February 1972, hinted at in his writings and numerous comments over the previous four years, constituted the most dramatic and, to knowledgeable experts in U.S. foreign policy, the most significant achievement of the Nixon presidency.