Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

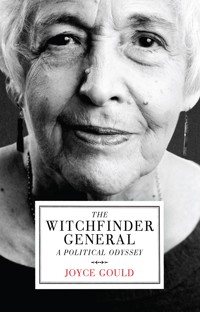

Labour's octogenarian powerhouse weaves together eighty years of fascinating personal, social and political history in her memoirs. From Boots Girl to Baroness, Joyce Gould boasts an impressive list of experiences and accomplishments. Through sixty-four years as a Labour Party member, she has fought for universal equality, for the right to a good standard of life for all, and for the spirit of her beloved party. The Witchfinder General is the political autobiography of the woman who notoriously made Labour electable again - nicknamed the Witchfinder General for her determination to end the debilitating discord of the 1980s by uncovering and removing the Militant Tendency - and as such it is a tender and frank depiction of the party over the past six decades. But more than that, it is a social history as seen through the eyes of someone who lived it, and a personal history of a pharmacist's apprentice turned political warrior, who has dedicated her life to making the world a better place. These memoirs document a long career in the fight for equality, the building of the modern Labour Party and the creation of the Britain we know today.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 435

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To my dear daughter Jeannette

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

David Marsh and Joanne Chambers, Abortion Politics

Betty Boothroyd, The Autobiography

David Denver, Colin Rallings and others, British Elections and Parties Yearbooks

Richard Heffernan and Mike Marqusee, Defeat from the Jaws of Victory

Giles Radice, Diaries 1980–2001

Eric Shaw, Discipline and Discord in the Labour Party

Tony Benn, The End of an Era: Diaries 1980–1990

Barbara Castle, Fighting All the Way

Jimmy Allison, Guilty by Suspicion

John Golding, Hammer of the Left

Harold Wilson, The Labour Government, 1964–70: A Personal Record

Eric Heffer, Labour’s Future

Peter Kilfoyle, Left Behind

Michael Crick, Militant and The March of Militant

Dennis Skinner, Sailing Close to the Wind

John Grayson, Solid Labour

Lucy Middleton (ed.), Women in the Labour Movement

Labour History Museum Archives

Particular thanks for memories:

Terry Ashton

Charles Clarke

Neil Kinnock

Gus McDonald

Sally Morgan

Richard Taylor

Larry Whitty

Peter Mandelson for recommending me to the National Democrats

Merlyn Rees for being a friend and sponsor

Roger Hough for my wonderful leaving party

Betty Lockwood my friend and mentor

To my staff at head office and in the regions and colleagues who guided me through twenty-four years

The legal team who guided me: Derry Irvine, Alan Wilkie and John Sharpe

My House of Lords colleagues, who were a snapshot of my political life

To all those people in Leeds who were dear friends and colleagues

To the fantastic Yorkshire women

To Sally Cline for her advice

To Lee Butcher for his research

To Jean Corston and Sally Morgan for their reminders

To Bernadette McGee, who spent many hours typing and re-typing – a very special thanks

To my family, Kevin and Jeannette, who put up with my impatience when I was not getting it right

And to many others who I have failed to name, but they know who they are

CONTENTS

A Socialist believes that all human beings, however different in gift and achievement, are equal in importance and dignity. That society shall be so contrasted, and incomes so distributed as to give everyone an equal chance of an active and enjoyable life.

Extract from This Is Our Faith, Labour publication (1950)

PRELUDE

Mae West said it, and I believe it: ‘You only live once – if you do it right that is enough’.

I sat on the couch in John Smith’s office one day in February 1993. I was there to tell him that I intended to retire at Easter from my post as director of organisation of the Labour Party. He asked me, ‘Will you be able to manage financially?’

‘Yes,’ I replied.

Then he said, ‘Joyce, would you like to go in the House of Lords?’

Six months of silence followed, six months of evasive answers when people asked me ‘What are you going to do with your retirement?’ I did not know and could not answer them until I learnt what my future was to be. The rules are absolute, everyone is sworn to secrecy until the official announcement is made.

On 31 July 1993 I returned home late at night from speaking at a conference in Madrid. There were four messages on the answerphone from John. ‘Ring me urgently tonight, no matter how late – going on holiday tomorrow.’ With trepidation I dialled his number. His opening words were, ‘I asked the Prime Minister, John Major, for ten new Labour peers but he has only given me three.’ Then he paused for what seemed a very long time. I steeled myself for disappointment. I thought he must be working out how to let me down gently. Then he uttered thirteen magic words: ‘And I have decided you are going to be one of the three.’ The announcement would be in The Times the next day.

Next morning early I made several urgent phone calls to my family, before they read it in the press. Seeing the announcement in print I still could not believe it was true. Was it real? Was I really going to be a baroness? Why me? Why did I deserve this honour? I knew that my work for the party had not been easy – that it had meant long hours, late nights and sometimes scary moments – but I had a job to do, so I got on and did it. Sometimes I don’t always understand the impact I made.

I found the answer four years later on the night of the Labour Party’s landslide victory in May 1997. At the celebratory party a young man, a stranger, crossed the room to speak to me. He said, ‘We would not have achieved this victory if you had not made the party electable.’ Then he disappeared into the crowd. I never discovered who he was – but, my goodness, did it make me feel it had been worthwhile!

I have always worried what the future might bring, what to expect, what opportunities might come my way, what challenges I might face.

When I served behind a pharmacy counter in Leeds and when I worked with wonderful Labour women in Yorkshire I never imagined that one day I would be in the House of Lords, that I would be Baroness Gould of Potternewton or that I might be addressed as ‘my Lady’, for what I had done seemed simple. I had felt passionate about several significant causes and worked to bring about change.

So I found myself moving into a completely fresh environment. I hurtled into the front room of politics. As the Yorkshire Post wrote, I went from Boots Girl to Baroness.

INTRODUCTION

EIGHTY YEARS OF CHANGE

Over the years in the centre of the political arena I heard many racy stories and saw many personal incidents. I was offered a great deal of money to tell all, dish the dirt, and say where the bodies were buried. I could not do that. For me it would have been out of character, an alien act, so I said no. Perhaps I was naive for it would have made me a rich woman.

I did not feel relaxed about a decision to write a book until I suddenly realised that I was an octogenarian. Although I did not feel old, my age made me re-consider my decision not to put pen to paper. I decided to write a personal story. Not only, as you might expect, about the disruptive and fraught days of the party in the 1970s and 1980s but about me. About the stages of my life, my origins, coming from intellectual Jewish stock, surviving a traumatic birth and a lonely childhood, growing up in a Jewish family with no money, run-of-the-mill school years, employment opportunities, being a mother and the events that followed joining the Labour Party. And ultimately my becoming a Labour peer.

Volumes have been written by politicians that cover my sixty-three years as a Labour Party member, through ten party leaders. But whilst many academics have put their own interpretation on that period, it dawned on me that there was no chronicle written by an insider: someone who had played a prominent role at local level in the Labour Party; someone who became a senior member of staff at head office; someone whose beliefs and passions were always intertwined with the women’s agenda. This last has been a winding thread throughout my life. Very few politicians, men or women, have written about the Labour Party’s attitude to women and their struggle for change.

Writing my story made me think not only about my history but also about how I define myself. How do others perceive me? What has made me who I am? Is it my heritage, my childhood? What have I done with my life? Have I used the years sufficiently wisely? I have of course been influenced by people I have met, but even more than that, what has driven me to take on so many challenges and how did I handle them?

As I mused about these questions the memories came flooding back, the changes, the disappointments and successes, the opportunities and the experiences. I thought about the great diversity of people I have met. I had the opportunity, whilst vice-president of Socialist International Women, a post I held for nine years, to meet and work alongside international socialist presidents and prime ministers. I learnt from women across the world about the challenges they faced, how they were campaigning for their democratic rights, for their freedom and justice. Those wonderful sisters were still battling for equality in spite of having experienced degradation and suffering, just because they were women. At the same time I recall the many wonderful moments when I joined with women in celebrations of success, to achieve the right to be a part of the decision making in their countries and the right to own a small piece of land. Importantly women achieved reproductive rights to determine the size of their family.

One day I was having a conversation with a friend, and I remember her reaction when I told her about my meeting with the first woman in space – ‘How many people can say that?’ she said. Valentina Tereshkova, who was president of the Soviet women’s committee, had been our hostess when I had headed two delegations of Labour women to the Soviet Union.

There was a further key question I had to try and answer, which everybody asked me: ‘Why do you feel so strongly, so passionately about the causes you have been involved in?’ It might have been my childhood environment which strongly influenced me. I recall the occasion as a seven-year-old evacuee when I lived in the maid’s quarters of a vicarage in Lincolnshire. We were never allowed in the rest of the house. Eventually we were asked to leave as the vicar decided it would be inappropriate for two young girls to be living in the house when the son of the family came home from Eton for his Christmas vacation.

At Roundhay High School for Girls, a girls-only grammar school, the divide in society became even more real to me. There were the posh girls who were the majority and there were the others who lived where I lived, downtown.

Those childhood experiences had a negative effect on me. Having two intelligent and very clever older brothers made it worse, not to mention a bevy of aunts who constantly asked me ‘Are you going to be as clever as your brothers?’ The consequence was that I felt inferior and insecure. I had a terrible lack of confidence which stayed with me for many years. It even manifested itself in my behaviour patterns. If I was late for a meeting I would not go in, I would turn round and go home. Even today I am obsessive about never arriving late.

I did not appreciate how important a moment it was when I paid my first sixpence to become a member of the Labour Party. Slowly I developed new skills, how to organise, arrange events and evolve my own views, thoughts and independence. When I told my friend Lewis Minkin that I was considering my memoirs, he said he had thought I would be just another wimpish wife always supporting my partner, irrespective of the issue. ‘How wrong I was,’ he said.

The Labour Party gave me a purpose. I could not know, of course, that it would take me up a ladder to the top of the party. I developed a real understanding of how deeply entrenched were the discriminations and injustices in society, against women, against those of colour. I recognised the enormity of the barriers that had to be climbed to establish the legal and cultural principles of equality. I was sure that through the Labour Party those cultural and prejudicial barriers could be overcome, exposed and challenged, and I fully committed myself to try to make that happen.

I was supported and encouraged by a wonderful group of Labour women, all fighting for the same causes, irrespective of where their politics placed them in the political spectrum of the party. What I did not appreciate was that it would take so long. I never believed that when I reached the age of eighty, equal pay for women would still be a dream, violence against women would still exist, and the concept of women’s rights as human rights would still not be understood.

What I was absolutely clear about was that to achieve these aims Labour had to be in power, locally and nationally. How true that turned out to be. Labour governments have been responsible for bringing about some fundamental political, societal and cultural change. To work for that Labour government as a volunteer I spent many hours and days and months, footslogging, leafleting and door knocking. I held every office at local level, both in the women’s movement and in the party, eventually going on to organise the party in the city of Leeds. These experiences gave me the ability to work with party members. They enabled me to lead a team. They showed me how to direct the work, whether it was on the doorstep or in a committee room or organising a public meeting, and how to make difficult decisions. Most of all I learnt how to stand my ground with the politicians on whom the future of the Labour Party rested.

I need to go back, back to my contemplation of the passage of time. Through the relentless pace of change both globally and here at home, the technological revolution that has transformed almost every aspect of our lives. There are 35 million cars on the road yet I never learnt to drive. Foreign travel is the norm, and credit cards have taken over from saving up or hire purchase. Men and women have been to the moon and walked in space. The speed of communication today means we rarely write letters, rather we use the computer, mobile phone or iPad. We send emails, texts and tweets, we Skype and use Facebook, in order to see and speak to each other across the world. We exchange our views by writing blogs, and gain our information from Google.

The structure of families has changed. Divorce has trebled since my childhood, marriage rates have declined, more than one-third of parents with children are cohabiting couples, lone parents or same-sex couples. This development of new partnerships, the growth in the number of step-families and more intricate family arrangements now shape the income and working patterns and living standards of families. Life for both women and men is now more complex.

The world is unrecognisable as the one I grew up in. That bastion of the past, the British Empire, has disintegrated. The geography of the world is different. Countries have exerted their independence, names of countries and towns have changed to bring back their original identities. We have seen the first woman prime ministers and the first black President of the United States. I am proud that as an active member of Anti-Apartheid I played a small part in supporting the years of struggle and the bravery of men such as Nelson Mandela who challenged and finally outlawed the evil of apartheid in South Africa. Europe has been re-defined; the symbol of the divide between East and West, the Berlin Wall, has been torn down, ultimately bringing with it the demise of communism and the introduction of democracy. The old Soviet Union has become Russia and has given independence to countries it had previously controlled. In the late 1980s and the early 1990s, I spent three years visiting many newly democratic countries, including South Africa and Russia, helping with the writing of their constitutions, and explaining the concept of democracy and the conduct of the free and fair elections.

These memories set me on the trail of the many ways in which key moments in my life had been inextricably linked with a range of social changes here at home and abroad. Recollections take me back to a time when my parents had to pay a few shillings each week to be on the doctor’s panel. If they hadn’t done, I doubt if I would be here today. Those payments were to be no more. The 1945 Labour government introduced a free health service for all, and on 5 July 1948 the National Health Service was born, becoming responsible for 480,000 hospital beds and the work of 1,125,000 nurses and some 5,000 consultants.

One year after I started grammar school as a fee-paying student, the 1944 Education Act made secondary education free for all. My parents were relieved of having to scrape together £25 a term to keep me at such an awful school.

My mother, and many other women who had no control over their own fertility, found their lives transformed by the advent of the contraceptive pill in 1961. It was still restricted, however, not free, and at that time only available to married women. Thirteen years later Barbara Castle introduced free family planning for all. For most women today taking the pill is a daily routine like brushing your teeth. The Family Planning Clinics, previously run by the Family Planning Association, of which I am now president, were taken over by the NHS. My first intervention into family planning services was to campaign across Yorkshire to ensure the retention of clinics in danger of being closed down. My second intervention was the long and arduous campaign to ensure the retention of the 1967 Abortion Act.

Women got the right to vote, and steadily advancements were made but the 1970s were the decade that fundamentally changed women’s aspirations and hopes. The Equal Pay Act provided equal pay for work of equal value. The Sex Discrimination Act was designed to remove sex discrimination on the grounds of employment, goods, services and education. My dear friend Betty Lockwood, then chief women’s officer of the party, was instrumental in making these fundamental improvements to women’s lives. The replacement of the Family Allowance with Child Benefit, moving payment from wallet to purse, was one of the most important social welfare advances at the time.

Unfortunately, a change of government in 1979 meant it was to be another eighteen years, following victory in 1997, before we were able to continue the progress started in the 1970s. Victory brought peace in Northern Ireland, the minimum wage and civil partnerships and devolution in Scotland and Wales.

These few examples identify for me how my dreams of so many years were beginning to come to fruition. But history shows how easily those fragile achievements could be weakened and overturned. However, my determination has not waned. In a different role I still want to help and encourage others to carry on. I am very delighted at my age when I am asked, as I frequently am, for advice and support by young women on how best to continue raising awareness of the challenges women still face.

I go back to the central question: what has prompted me to be involved in these causes. My mind goes to my paternal grandfather, whom I never met, although history records show his many achievements in improving the lives of others. Did he pass his genes to my father, and did I inherit them?

CHAPTER 1

WHO I AM

I have always had the urge to know who I am. Where did I originate from? Was there someone amongst my forefathers with whom I can feel an empathy?

My four grandparents were émigrés, part of the Jewish exodus from Eastern Europe. They all left Lithuania in the late 1800s, but at different times; they left to escape persecution and the extremes of poverty. They came with the hope of a better and more secure life.

When they arrived they embarked on different paths, paths that were ultimately destined to come together. My paternal grandfather, Joshua Aric, later known as Simon, son of Solomon Manson, was the first to arrive. He came in 1874 at the age of nineteen. The census in 1881 records him as a tailor, but his ambition was to be a rabbi, a Jewish minister. Interestingly, the 1908 Kelly’s Directory lists him as a rabbi and a grocer.

Before he could become a rabbi he had to prove his credentials. This meant he had to receive a testimonial from the Jewish community in the home town he had left behind. Five years later it arrived, written in Yiddish, from the Jewish Ecclesiastical Church Court in Darishinishok. A copy now sits on my wall; its translation shows that Joshua Aric Manson was descended from a long line of rabbis, Jewish judges and theological students.

Simon’s great-grandfather Menachim Manele of Kalvera was famed throughout Russia and Poland for his teachings. His great-great-uncle was the chief rabbi of the Jewish Ecclesiastical Church Court of Dineberg and author of a definitive work called Judah of Calvara: The Ethics, published in Lithuania in 1800, copies of which now reside in the Bodleian and the British Library. Simon was following a family tradition.

Simon had settled in Leeds. He became a respected rabbi of the new Belgrave synagogue in Briggate, the main shopping street in the centre of the city. How exciting it must have been that the first wedding to be held in his synagogue was his own! He married the slightly younger Kate Frieze. Kate came from affluent Lithuanian peasant stock and had been with him on the boat from Lithuania.

Simon’s salary of £3 a week was probably enhanced by the generosity of his congregation, enabling his family of thirteen children, seven boys and six girls, to live in a substantial four-storey house, 8 Elmwood Street. It was in the heart of the Jewish settlement in Leeds, in the parish of Leylands St Thomas, locally known as a ghetto without bars.

My grandfather was a remarkable man of his time whose interests and good work centred on the Jewish people but embraced the whole community. This is particularly remarkable because in those days Jews had little contact with non-Jews and the close-knit community did not generally participate in civic life.

The majority of Jewish people tended to vote Liberal. Grandpa Manson was an active member of the Leeds Liberal Party, canvassing door to door in local and general elections. That kind of political activity was unique for a rabbi. I have followed him in his belief that only left-wing politics was the means of improving people’s lives.

The level of Simon’s charitable work was formidable. He was one of the founders of the Jewish Work People’s Hospital Fund and became its first president. He was a key participant in the Jewish Board of Guardians and was the first Jewish minister of religion to pay hospital and prison visits. He had a real commitment to improving health services. He was a member of the board of Leeds General Infirmary, where he launched a kosher kitchen so that for the first time Jewish people could have kosher food in hospital. He was also on the board of the Women’s and Children’s Hospital and became president of the Friendly Societies Medical Association and of the Jewish Sick Aid Society. The renowned surgeon Sir Berkeley Moynihan, later Lord Moynihan, was his close friend.

When Simon died at the age of sixty-nine, his obituary in the Yorkshire Post highlighted his many achievements, extolling his commitment to the development of the Jewish and non-Jewish communities in Leeds with the words ‘his loss will be felt by all sections of the community in the city’. On the day of his funeral the streets from his house to the synagogue were crowded with people from all faiths, watching the cortege pass. Many members of his congregation walked with the family behind the hearse.

My cousin Rose recalled him as a tall, fair-haired man with blue eyes that my father inherited. I regret that I never met him; this influential, inspirational man, for curiously I feel a connection with him. He was a man with a social conscience – did I inherit that from him? Nor did I meet Kate, my grandmother, as she, like Simon, died before I was born. I know little about Kate, maybe because the role of women is seen as of little significance in family history.

It is strange that when Simon came to England he was called Manson, a north Scots name, the surname also of his father Solomon. Jews in Lithuania in the first part of the nineteenth century did not have surnames so where did Manson come from? Perhaps some Scottish engineer had wormed his way into the family, or more likely the name had been the German Manssohn, or son of man. Wishing to find out, my brother consulted a genealogist, Professor Ludwik Finkelstein, pro-vice-chancellor of City University, London. He suggested that the old family name Manele, which appears on Simon’s grave, was a diminutive of Emmanuel or ‘Son of God’. I was not entirely convinced, but it did bring a little light to a corner of a rather overgrown graveyard, in which Manele had been misread as Manela with its misleading suggestion of sunny Spain rather than grim Lithuania.

My maternal grandparents, Harry and Jenny Schneider, were anglicised to Taylor, a decision perhaps made by the customs officer as they landed. They were both born in 1872, and came to this country as children. Grandpa Harry Taylor was accompanied by his parents, younger sister and grandparents. When his mother died, his sister Bessie emigrated to New York with their father and grandparents. Through all the intervening years, Harry and Bessie kept in touch with each other by correspondence and the exchange of pictures.

On 17 January 1948, at the age of seventy-six, Grandpa Taylor set sail on the Queen Elizabeth to visit Bessie at her home in Tennsville, Florida. This was a big event in a very small town. ‘Man meets sister here after 62 years’ was the headline in the local paper. Evidently, Grandpa was pleased to find goods so plentiful; maybe in response he told everyone that there were no empty stomachs in Britain. He indicated that unlike the period after the First World War rich people and poor people had the same opportunities to buy the necessities of life. How I wish that was an accurate statement. Until this visit, the family in the UK were unaware that Harry Taylor had two half-brothers living in the states and as a consequence we had found another family of cousins.

My memory of Grandpa and Grandma Taylor is of a couple who had a happy and contented marriage. Their home was the centre of the family. Through our young teens I would go there after school with my sisters Cynthia and Heather and my cousin Gerald. It was where our mothers were gathered. My brothers David and Louis, being older, were exempt from the ordeal of these daily visits. Our first duty was to pop in to say hello to our grandma, a clever lady, but who through illness was confined to bed. I remember this little old lady lying there, with the longest plait I have ever seen. Grandpa was a stocky, round man with white bristles on his chin which he rubbed on my cheeks, affectionately, to greet me.

Their house was a wondrous place. There was always the aroma of fruit being dried over the vast kitchen range, tied to long lines of string stretching from one end of the large kitchen to the other. The scent of apples, pears, plums, cinnamon and ginger pervaded the house. I waited eagerly for the time when the fruit was dry enough for us to eat. The large garden was full of crab apple trees, constantly scrumped by the local youths.

The great excitement was when Grandpa Taylor would bring home American and Canadian Jewish servicemen for a genuine Jewish meal. They always looked handsome in their uniforms, and arrived with their pockets filled with Chiclets chewing gum, chocolate and other goodies. This was when sweets were rationed.

How did the Mansons’ and the Taylors’ lives become entwined? The story goes that one day Kate Manson met Jenny Taylor, who was wheeling my mother Fanny, her first-born, in her pram. Kate peeped into the pram and announced there and then, ‘She will be for our Shamie,’ my father, her eleventh child.

My father Solomon Joseph (known as Sydney), born on 23 June 1893, was small in stature but a smart, dapper, sociable man, always conscious about his appearance. There are many differing versions of his ambitions as a young man: for instance, why when he was at grammar school did he never gain the matriculation certificate? My cousin Rose suggested that he wanted to be an actor. He was intelligent and literate, wrote plays and took part in amateur dramatics. At the age of twenty-one, Sydney joined the army where he was an orderly in the Royal Army Medical Corps, stationed at the limb-fitting centre in Roehampton. He may have been on the front line in the war, but I have found no evidence and he never talked about his war years.

My father’s only vice was that he smoked sixty Woodbines a day, maybe a throwback to the days when part of his job as an orderly was to dole out cigarettes to the convalescent soldiers. He left the army without a trade and without a job. How he earned a living over the next few years, I do not know.

My parents’ arranged marriage, which to many of us today seems extraordinary, took place in Middlesbrough in 1921, where Grandpa Taylor, a master painter and decorator, ran a successful paint and wallpaper business. Not everyone was happy; members of the Manson family saw it as an unsuitable match. Indeed Kate wanted my father to escape by emigrating to America to join his younger brother Leslie, but Grandpa Manson would have none of it. The shiddach had been arranged, and it must be honoured.

What appears not to have been honoured was the promised dowry and the job Grandpa Taylor would give my father; neither transpired. So started the antagonism between the two families, who were never seen together again. Grandpa Taylor did, however, persuade Alderman Morris, owner of Morris’s Wallpaper Store and the first Jewish Lord Mayor of Leeds to give Dad a job as a commercial traveller. The great luxury was the car that accompanied the job. The disadvantage was that being a commercial traveller meant moving away from Leeds. First my parents moved to Dundee, where my brothers were born: Julius David in 1926 and Louis Joshua two and a half years later. Next came Nottingham, and a bungalow my mother loved. Finally they returned to Leeds, where I was born, on 29 October 1932 in Mexborough Street. As children there was an enormous contrast between my brothers. David had straight black hair and Louis, the pretty one, a mass of blond curls. Now that they are both grey-haired they look like brothers.

The late 1930s saw my father unemployed until 1939, when he became a full-time air raid warden, a well-known person in the neighbourhood. He was always there to help our neighbours, giving advice, drafting letters, sometimes to my mother’s annoyance for he spent too little time at home and too much assisting others. He was a man of routine. Each night he would have his cocoa, set the fire ready to be lit the next morning and polish his shoes. My mother used to say I was a father’s girl. I helped him on his allotment in Potternewton Park, and on a Friday night we would go to see a man who sold sweets. I came home with more than any ration allowed. Rummaging through old papers, I found his certificates qualifying him to give first aid and to be a firefighter. His handwritten ARP book described different types of bombs and the actions that had to follow an air raid. Part of it I had used for pasting in recipes I might make one day. I have always felt that it is a tragedy that his abilities never achieved a better life for him.

Mother was eighteen months younger than my father, but to me she always appeared older. She was small, 4 feet 11 inches tall, dark with a sallow complexion, and shy. She was often ill, spending time in hospital with severe colitis, which dogged her adult life.

At just short of forty years old, my mother had no knowledge that she was pregnant. I suddenly appeared on 29 October 1932, premature and weighing only one and three-quarter pounds. My Aunt Kitty, one of my mother’s younger sisters and a nurse who happened to be in the house at the time, later proudly told my friends, ‘Joyce just dropped into a chamber pot.’ My brothers remember the midwife, Nurse Ness, appearing quickly, as our neighbour had run out into the street to find help. She also found Dr Pearce, our family doctor, who rushed up the stairs to my mother’s bedroom. Had they not arrived so quickly, I would not be here today writing this memoir. Louis said he hid in his bedroom just opposite to where I was being born, wondering what was happening. David remembers my father sitting at the foot of the stairs and crying. It took six weeks before my birth was registered – why? Unfortunately there is no one still alive who can give me the answer; even if I wasn’t expected to survive I still had to be registered.

My mother was the eldest of nine, six sisters and three brothers. Because of her illness my brothers and I spent much of our childhood living with relatives. My aunts spent whole afternoons gossiping, sometimes malevolently, about their neighbours, friends and other members of the extended family. Mother took little part in this gossip, for she was a quiet, timid, fragile woman who I know would not have been able to respond to their often nasty comments, some directed at my father. The sisters were quick to blame him for my mother’s ill-health and her perceived unhappiness; I am not sure that was true but to me she always seemed sad.

My abiding memory of my mother is that she spent her life in a constant round of cooking and cleaning. My daughter Jeannette’s memory is of ‘Little Grandma’, as she was called, teaching her to make rock buns. She was extremely superstitious. She would never refuse to buy heather from a gypsy at the door, and always remembered which shoulder to throw salt over for luck. But she did have a wicked sense of humour, describing the woman who lived next door as ‘red hat, no knickers’. She hardly went out except for the daily walk the one block to her father’s to meet up with her sisters or take our dog Nelly for a walk. On occasion I would persuade her to put on some make-up, wear a bra and come with me to one of our local cinemas, the Gaiety or the Forum, which was the first cinema to show the much-awaited For Whom the Bell Tolls starring Gary Cooper and Ingrid Bergman. We went to the first performance.

My parents kept a Jewish house. My father went to the synagogue most Saturdays with Grandpa Taylor. In a book on Jews in Leeds, I found a photograph of them both walking up Chapeltown Road returning from their prayers. My mother prayed on the candles every Friday on the eve of Sabbath. We then sat down to traditional chicken soup, a chicken dinner and, on special occasions, strudel to follow.

For the week of Passover the special pots were brought out, carefully washed ready for use, and the cupboards where the Passover food was to be stored were scrubbed clean. The first two nights were celebrated in the traditional grand Seder style at Grandpa Taylor’s. I wore my best dress and proudly walked with the family from our house to his. The large table with its gleaming white tablecloth was laid with the best china and glasses. My father led the service that accompanied the meal. The meal started with a small piece of onion or boiled potato dipped in salt water, to represent pleasure and freedom with the family. Five cups of kosher wine were drunk to symbolise joy and happiness, giving me my first taste of alcohol. It was late at night that, very tired, I walked with the family the block back home, and so the meal went on at my grandfather’s house, accompanied by the prayers for salvation.

In school, the few Jewish girls were exempt from daily prayers. We ate packed lunches, school lunches not being kosher. This isolated us from the rest of the school.

Judaism was present throughout my childhood. I went to B’nai B’rith and joined the Judean Club, both groups for Jewish teenagers. I attempted, unsuccessfully, to learn Hebrew, and had mostly Jewish friends. But only my historical past is Jewish. Nevertheless my becoming a member of the House of Lords was reported in all the Jewish newspapers. It is a great sadness to me that my parents were not alive to read their words. I think they would have been proud.

My mother died at the age of sixty-six, during an operation for her colitis. Her younger brother Barney woke me up in the night to tell me in person, as I did not have a telephone. Ten years later, whilst I was at my first Labour Party conference in Brighton as a full-time official in 1970, my father died. Dad had been ill for a while in Donisthorpe Hall, a Jewish old people’s home, but despite this, I had been assured by the doctor that I should go to the conference. At the conference on the Sunday morning Alderman Raymond Ellis, who was a trustee of Donisthorpe Hall, came to find me to tell me. Immediately after, Jeannette phoned me. I caught the first train from Brighton to Victoria, crossing in London to King’s Cross, but I was too late for the funeral. Jewish funerals are held twelve to twenty-four hours after a person has died. It is something I have always felt guilty about. The job should not have come first.

Although I do not believe in fate that one’s destiny is ordained, life is full of coincidences. There have been links, even if somewhat tenuous, to the Labour Party since the day I was born. That tenuous connection arises from the coincidence that nineteen years later Alec Baum, the son-in-law of the helpful neighbour who found Nurse Ness, signed me up as a member of the Labour Party, and Dr Pearce’s brother Solly was the Labour Party’s kingmaker in Leeds. I worked closely with Solly for many years. During our many policy disagreements he was known to mutter, without malice, ‘It’s all my brother’s fault’. Dr Pearce was no doubt of a different political persuasion to his brother for he refused to join the NHS, setting up a private practice in the nearby town of Harrogate.

I have very little memory of my early years, almost a blank. My brother David has suggested that I may have blocked them out, because of my mother’s illnesses and her many stays in hospital. Unlike my mother I have been extremely fortunate that my early birth has not affected my health. Photographs show me as a chubby child, with my dresses going straight down over my tum from collar to hem. Dr Pearce found that unbelievable.

Because of my lapses of memory up to the age of seven I only recollect two short stays in hospital. One was in the dark dreary Leeds Dispensary where I had my tonsils and adenoids out and the other was in the Infectious Disease Hospital with measles. My mother was also in hospital at the time and I was put in a cot bed in the centre of the ward as it was the only place I could go. This was extremely humiliating and scary for a little girl of five.

In 1939, when I was six, war broke out and the big evacuation of children from danger zones began. And so started a new chapter in my life.

CHAPTER 2

FORMATIVE YEARS

At nearly seven years of age I was standing in a long line of boys and girls at Leeds City station. I carried a white pillowcase that contained my clothes and over my shoulder a cardboard box holding my gas mask. The Second World War had been declared and the children of Leeds were evacuated to places where supposedly we would be safe.

I did not know what was happening. I am sure I felt excitement, definitely bewilderment and a lack of understanding. I had no idea where I was going as I waited to catch a train supposedly to safety. As it turned out I was being sent to the Lincolnshire countryside, surrounded by American airfields. This was not the most sensible thing to do, as I discovered when my bedroom ceiling came down when the village I was living in was bombed. When I returned home from Lincolnshire eighteen months later, if the sirens went off we rushed to take cover in Grandpa Taylor’s cellar.

Paradoxically Pamela Saltman, who became my closest friend, and her family moved from Hull to Leeds, seen as a safer place to spend the war. They never returned to Hull. It was even more ludicrous that in our small house in Leeds we looked after Jewish families escaping the bombing in London. My memory is of a tallish, fair, wan and depressed-looking woman and her young son sleeping in our front room.

Television programmes which today show children being evacuated assume that it was only children from London who were sent from their homes and families. There has been very little account of the many thousands of children from other parts of the country who were separated from their families, to live with strangers in strange places.

I have a memory of being put on a bus outside my school, Cowper Street Infants’ School, to travel to Leeds City station. I had never seen a railway station before. Families were split up, segregated into groups according to age, and I was separated from my brothers. David and Louis ended up in Lincoln, whilst I arrived at a village eight miles from Newark called Brant Broughton, where I was told by the locals to pronounce it ‘Brooton’.

Still bewildered, I was ushered into the old Quaker Meeting House where I stood in a row with other boys and girls of my age. We stood like little orphans waiting to be picked out by some kind person willing to take one of us to their home. Eventually I and another Jewish girl, Ruth Rosenthall, were chosen by a dear elderly woman – at least she seemed old to me – whose name I cannot recall. We lived in a typical country thatched cottage, all so different and strange. I had never been in the countryside before. It was awesome seeing these very different, beautiful houses with gardens filled with flowers. I was used to houses in terraces, maybe with a narrow strip of grass in front or with the front door opening straight onto the street. I was fascinated by the pond in the centre of the village. I was warned not to go too close. I still have pictures of the village that show the blacksmith’s shop, the School House and the wide main street. It was a street where many of the houses dated back to the eighteenth century. They were country retreats for the London gentry, who worshipped in the church of St Helen, reputed to have the most elegant spire in Lincolnshire.

My stay in the thatched cottage was short. It proved too much for this kind elderly woman to look after two small girls. Ruth and I moved on, to the impressive stone-built vicarage, where we lived in the servants’ quarters. We were not allowed in the main house, with its wood-panelled walls and big pictures. At Christmas Ruth went home back to Leeds and I went to live with the parents of Eileen Watson, one of the maids at the vicarage. Eileen’s father was the village blacksmith, and there were pigs in the back garden. Another new exciting experience: I had never seen a pig before and I had certainly never heard one grunt, but I soon realised they were harmless and I adored feeding them. There was an apple orchard. I was fascinated by the rows and rows of trees with fruit hanging off them. We lived on apples, baked, stewed or in pies, and for the following eighteen months, I was very happy. It was a completely new life which I loved.

A great excitement for me was to be carried on the shoulders of John, the farm labourer who lodged with the Watsons. He appeared big and handsome and I adored him.

During those eighteen months living this new life family visits were infrequent. My father came once with my brothers and stayed overnight. Mother also only came once, travelling on the train to Lincoln and then on the bus. She was delighted to go home with a bag of apples from the orchard, a real treat as fruit was scarce. My brothers left Lincoln and went home after a few months.

Before I returned home, Mr Watson retired and the family moved to an even smaller village, Scragglethorpe. I missed the pigs and big John but we still had apple pies. I stayed for a few months. For several years I kept in touch with Eileen, who married a policeman and moved to Lincoln.

I vowed I would never go back to Brant Broughton, afraid that all my memories of this pretty village would be shattered and that it would have been filled with little box-like houses. But many years later, on a holiday in Lincolnshire with a dear friend, Jill McMurray, travelling in her little Beetle, I did go back. To my delight nothing had changed. Although the vicarage was no longer the vicarage, the vicar now living in much more modest accommodation, the blacksmith’s was just as I remembered it minus the pigs. Visiting the graves of Mr and Mrs Watson was a moving experience, for they had been such kind and loving people.

My brother David recalls my coming home. I walked in and greeted my parents in a full-blown Lincolnshire accent: ‘’Ello Maister, ’ello Missus!’ I don’t think it was long before I returned to my usual Yorkshire brogue. Number 25 Hamilton View was a smallish house and I lived there with my parents and brothers until they departed and I got married. It was an end-of-terrace house next to a vacant lot. It should not have been the last one in the street but the builder went bankrupt and a spare piece of stony ground was left unbuilt upon. The thin outer wall of our house was a great place to bounce a ball. The thud, thud of the balls caused endless frustrations and despair to my mother. Pamela and I and other youngsters spent hours playing on this small piece of ground. One of those youngsters, Gerald Kaufman, who lived in the next street, was later to become an MP.

Downstairs was the Best Room, rarely used, with a monstrous ebony cabinet covered in cameos, and one other large room where everything happened. We sat by the fire, listened to the radio, did homework, and ate meals on a large table protected by a brown plush tablecloth, and where later the black-and-white television became the focal point.

I went back to the primary school at Cowper Street for a year or so before I sat the 11-plus examination. The school was on a hill, the girls in the upper building and the boys down below. A typical school of its time, it had classrooms round a big central hall, the floor of which was made of glass. Punishment for bad behaviour meant standing on the glass, much to the enjoyment of the boys down below. We were well looked after, with school milk and a teaspoon of malt each day. The school nurse regularly made sure we didn’t have nits and that we looked after our teeth.

I was told that my chance to go to grammar school was to pass the 11-plus examination, but that I had only one chance. The exam was held in another school, which meant crossing the major Chapeltown Road. I was with my cousin Cynthia, I was ten and she was eleven and a half. With either nervousness or excitement I walked into the road and was knocked down by a passing car. I picked myself up and went on to the exam, unaware of any injury I might have done to myself. I failed and later learnt my writing was illegible as I had injured my elbow. I swore Cynthia to secrecy, my parents only being told of the accident when it was too late for me to re-sit the exam. I went to grammar school as a fee-paying student, which was financially a burden for the family. They were released from that burden by the 1944 Education Act, introduced by the coalition government of that time.

Then loomed my future for the next six years at Roundhay High School for Girls. Not a school of my choice, my parents chose it because my brother Louis was already at the boys’ school. It was the wrong decision, as it separated me from most of my friends, particularly my friend Pamela, who went to Allerton High School for Girls. The decision was purposeless as I was not permitted to talk to anyone in the boys’ school – not even my brother.

One’s school days are said to be the best days of one’s life. For me that was a myth, as they were merely days I had to get through. School was a necessity, not a pleasure. I felt insecure and unhappy for the whole of my years at the school I did not choose. However, the six years passed largely uneventfully, although I found sport difficult, being very left handed. It was impossible for me to play tennis or hockey holding a racquet or stick with my right hand, which was insisted upon. I was happier playing the lowlier games of netball and rounders.

My time at Roundhay started badly. As a paying pupil from the ‘wrong side of the tracks’, I had a pre-school interview with Miss Hilda Nixon, the headmistress. She asked me, a nervous child of ten, a completely ridiculous question: ‘How would you set a table for tea?’ I am not sure whether I got the cutlery in the right order but when she asked, ‘Would you put a bowl of flowers on the table?’ I replied that my mother did not like flowers on the table when we are eating. That was clearly not the right thing to say, and defined where I sat in her social scale.

Roundhay High School for Girls was in the affluent part of north-east Leeds, which is where most of the fee paying pupils came from. The scholarship girls came from the more working-class area where I lived. I never joined the Old Girls’ Society, I had no desire ever to go back, but perhaps I should have done so as a baroness.