5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

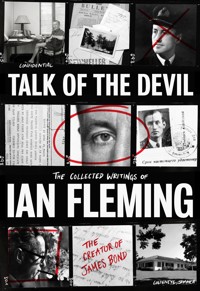

- Herausgeber: Ian Fleming Publications

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

'On November 2nd armed with a sheaf of visas...one suitcase...and my typewriter, I left humdrum London for the thrilling cities of the world...'In 1959, Ian Fleming, the creator of James Bond, was commissioned by the Sunday Times to explore fourteen of the world's most exotic cities. Fleming saw it all with a thriller writer's eye. From Hong Kong to Honolulu, New York to Naples, he left the bright main streets for the back alleys, abandoning tourist sites in favour of underground haunts, and mingling with celebrities, gangsters and geishas. The result is a series of vivid snapshots of a mysterious, vanished world.Take an adventure with the one and only Ian Fleming to Hong Kong, Macau, Tokyo, Honolulu, Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Chicago, New York, Hamburg, Berlin, Vienna, Geneva, Naples and Monte Carlo. An unforgettable and uniquely personal journey through the sights, sounds, food and drink of some of the thrilling cities in the world.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 381

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Thrilling Cities

Thrilling Cities

IAN FLEMING

Contents

Author’s Note

1: Hong Kong

2: Macao

3: Tokyo

4: Honolulu

5: Los Angeles and Las Vegas

6: Chicago

7: New York

8: Hamburg

9: Berlin

10: Vienna

11: Geneva

12: Naples

13: Monte Carlo

Author’s Note

There is very little to say as an introduction to this book that is not self-evident from its title, but there are one or two comments I would like to make on its origins.

These are thirteen essays on some of the thrilling cities of the world written for the Sunday Times in 1959 and 1960 Seven of them are about cities round the world, and six round Europe.

They are what is known, in publishing vernacular, as ‘mood pieces’. They are, I hope – or were, within their date – factually accurate, but they do not claim to be comprehensive, and such information as they provide is focused on the bizarre and perhaps the shadier side of life.

All my life I have been interested in adventure and, abroad, I have enjoyed the frisson of leaving the wide, well-lit streets and venturing up back alleys in search of the hidden, authentic pulse of towns. It was perhaps this habit that turned me into a writer of thrillers and, by the time I made the two journeys that produced these essays, I had certainly got into the way of looking at people and places and things through a thriller-writer’s eye.

The essays entertained, and sometimes scandalized, the readers of the Sunday Times, and the editorial blue pencil scored through many a passage which has now been impurgated (if that is the opposite of expurgated) in the present text. There were suggestions that I should embody the two series in a book, but I was too busy, or too lazy, to take the step until now, despite the warning of my friends that the essays would date.

I do not think they have dated to any serious extent and, rereading them, they seem, to me at any rate, to retain such freshness as they ever possessed. The cities may have changed minutely, this or that restaurant may have disappeared, a few characters have died, but I stick to the validity of the landscapes, painted with a broad and idiosyncratic brush, and I have embellished each chapter with stop-press indices of ‘Incidental Intelligence’ which should, since they were provided for the most part by foreign correspondents of the Sunday Times, be of value to the traveller of today.

Nothing remains but to dedicate this biased, cranky but at least zestful hotchpotch to my friends and colleagues on the Sunday Times in London and abroad, and particularly to a man called ‘C.D.’, who pulled the trigger, and to Mr Roy Thomson who cheerfully paid for these very expensive and self-indulgent peregrinations.

I.L.F.

1

Hong Kong

If you write thrillers, people think that you must live a thrilling life and enjoy doing thrilling things. Starting with these false assumptions, the Editorial Board of the Sunday Times repeatedly urged me to do something exciting and write about it and, at the end of October 1959, they came up with the idea that I should make a round trip of the most exciting cities of the world and describe them in beautiful, beautiful prose. This could be accomplished, they said, within a month.

Dubiously I discussed this project with Mr Leonard Russell, Features and Literary Editor of the paper. I said it was going to be very expensive and very exhausting, and that one couldn’t go round the world in thirty days and report either beautifully or accurately on great cities in approximately three days per city. I also said that I was the world’s worst sightseer and that I had often advocated the provision of roller-skates at the doors of museums and art galleries. I was also, I said, impatient of lunching at Government Houses and of visiting clinics and resettlement areas.

Leonard Russell was adamant. ‘We don’t want that sort of thing,’ he said. ‘In your James Bond books, even if people can’t put up with James Bond and those fancy heroines of yours, they seem to like the exotic backgrounds. Surely you want to pick up some more material for your stories? This is a wonderful opportunity.’

I objected that my stories were fiction and the sort of things that happened to James Bond didn’t happen in real life.

‘Rot,’ he said firmly.

So, wishing privately to see the world, however rapidly, while it was still there to see, I purchased a round-the-world air ticket for £803 19s. 2d., drew £500 in travellers’ cheques from the Chief Accountant and had several ‘shots’ which made me feel sore and rather dizzy. Then, on November 2nd, armed with a sheaf of visas, a round-the-world suit with concealed money pockets, one suitcase in which, as one always does, I packed more than I needed, and my typewriter, I left humdrum London for the thrilling cities of the world – Hong Kong, Macao, Tokyo, Honolulu, Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Chicago, New York.

On that soft, grey morning, Comet G/ADOK shot up so abruptly from the north–south runway of London Airport that the beige curtains concealing the lavatories and the cockpit swayed back into the cabin at an angle of fifteen degrees. The first soaring leap through the overcast was to ten thousand feet. There was a slight tremor as we went through the lower cloud base and another as we came out into the brilliant sunshine.

We climbed on another twenty thousand feet into that world above the cotton-wool cloud carpet where it is always a beautiful day. The mind adjusted itself to the prospect of twenty-four hours of this sort of thing – the hot face and rather chilly feet, eyes that smart with the outside brilliance, the smell of Elizabeth Arden and Yardley cosmetics that B.O.A.C. provide for their passengers, the varying whine of the jets, the first cigarette of an endless chain of smoke, and the first conversational gambits exchanged with the seatfellow who, in this instance, was a pleasant New Zealander with a flow of aboriginal jokes and nothing else to do but talk the whole way to Hong Kong.

Zürich came and the banal beauty of Switzerland, then the jagged sugar-icing of the Alps, the blue puddles of the Italian lakes and the snow melting down towards the baked terrazza of the Italian plains. My companion commented that we had a good seat ‘viewwise’, not like the other day when he was crossing the Atlantic and an American woman came aboard and complained when she found herself sitting over the wing. ‘It’s always the same,’ she had cried. ‘When I get on an aircraft all I can see outside is wing.’ The American next to her had said, ‘Listen, Ma’am, you go right on seeing that wing. Start worrying when you can’t see it any longer.’

Below us Venice was an irregular brown biscuit surrounded by the crumbs of her islands. A straggling crack in the biscuit was the Grand Canal. At six hundred miles an hour, the Adriatic and the distant jagged line of Yugoslavia were gone in thirty minutes. Greece was blanketed in cloud and we were out over the Eastern Mediterranean in the time it took to consume a cupful of B.O.A.C. fruit salad. (My neighbour told me he liked sweet things. When I got to Los Angeles I must be sure and not forget to eat poison-berry pie.)

It was now two o’clock in the afternoon, G.M.T., but we were hastening towards the night and dusk came to meet us. An hour more of slow, spectacular sunset and blue-black night and then Beirut showed up ahead – a sprawl of twinkling hundreds-and-thousands under an Arabian Nights new moon that dived down into the oil lands as the Comet banked to make her landing. Beirut is a crooked town and, when we came to rest, I advised my neighbour to leave nothing small on his seat, and particularly not his extremely expensive camera. I said that we were now entering the thieving areas of the world. Someone would get it. The hatch clanged open and the first sticky fingers of the East reached in.

‘Our Man in the Lebanon’ was there to meet me, full of the gossip of the bazaars. Beirut is the great smuggling junction of the world. Diamonds thieved from Sierra Leone come in here for onward passage to Germany, cigarettes and pornography from Tangier, arms for the sheikhs of Araby and drugs from Turkey. Gold? Yes, said my friend. Did I remember the case brought by the Bank of England in the Italian courts against a ring that was minting real gold sovereigns containing the exactly correct amount of gold? The Bank of England had finally won their case in Switzerland, but now another ring had gone one better. They were minting gold sovereigns in Aleppo and now saving a bit on the gold content. These were for India. Only last week there had been a big Indian buyer in Beirut. He had bought sacks of sovereigns and flown them to a neighbouring port where he had put them on board his private yacht. Then he sailed to Goa in Portuguese India. From there, with the help of conniving Indian frontier officials, the gold would go on its way to the bullion brokers in Bombay. There was still this mad thirst for gold in India. The premium was not what it had been after the war, only about sixty per cent now instead of the old three hundred per cent, but it was still well worth the trouble and occasional danger. Opium? Yes, there was a steady stream coming in from Turkey; also heroin, which is refined opium, from Germany via Turkey and Syria. Every now and then the American Federal Narcotics Bureau in Rome would trace a gang back to Beirut and, with the help of local police, there would be a raid and a handful of prison sentences. But Interpol, he urged, really should have an office in Beirut. There would be plenty to keep them busy. I asked where all the drugs were going to. To Rome and then down to Naples for shipment to America. That’s where the consumption was, and the big prices. Arms smuggling wasn’t doing too well now that Cyprus was more or less settled. Beirut had been the centre of that traffic – mostly Italian and Belgian arms – but now there was only a trickle going over, and the sheikhs had enough of the light stuff and wanted tanks and planes, and these were too big to smuggle.

We sat sipping thin lemonade in the pretentious, empty airport with scabby walls and sand blown from the desert on the vast, empty floors. The doors had been locked upon us and our passports impounded by surly Lebanese police. Flight announcements were first in Arabic – the hallmark of a small state playing at power. It was good to get back to one’s comfortable seat in the Comet and to be offered chewing gum by a beautiful Indian stewardess in an emerald sari with gold trim – not only the ‘magic carpet’ routine but necessary to cope with our changing groups of local passengers. We soared up again into the brilliant night sky and then there was nothing but the desert and, forty thousand feet below, the oil wells flaring in the night. (My neighbour said that the lavatories at Beirut had been dreadful. He added that in an Iowa hotel the lavatories were marked ‘Pointers’ and ‘Setters’.)

I had armed myself for the flight with the perfect book for any journey – Eric Ambler’s wonderful thriller Passage of Arms, a proof copy of which had been given to me by Mr Frere of Heinemann’s for the trip. I had only been able to read a few pages and I was now determined to get back to it. I offered another book to my neighbour but he said he hadn’t got much time for books. He said that whenever someone asked him whether he had read this or that, he would say, ‘No, sir. But have you red hairs on your chest?’ I said that I was sorry but I simply must read my book as I had to review it. The lie was effective and my companion went off to sleep hogging more than his share of the arm-rest.

Bahrain is, without question, the scruffiest international airport in the world. The washing facilities would not be tolerated in a prison and the slow fans in the ceilings of the bedraggled hutments hardly stirred the flies. Stale, hot air blew down off the desert and there was a chirrup of unknown insects. A few onlookers shuffled about with their feet barely off the ground, spitting and scratching themselves. This is the East one is glad to get through quickly.

Up again over the Arabian Sea with, below us, the occasional winking flares of the smuggling dhows that hug the coast from India down past the Aden Protectorate and East Africa, carrying cargoes of illegal Indian emigrants on their way to join fathers and uncles and cousins in the cheap labour markets of Kenya and Tanganyika. Without passports, they are landed on the African continent anywhere south of the Equator and disappear into the bidonvilles that are so much more hospitable than the stews of Bombay. From now on, we shall be in the lands of baksheesh, squeeze and graft, which rule from the smallest coolie to the Mr Bigs in government.

Ten thousand feet below us a baby thunderstorm flashed violet. My neighbour said he must get a picture of it, groped under his seat. Consternation! A hundred and fifty pounds’ worth of camera and lenses had been filched! Already the loot would be on its way up the pipeline to the bazaars. The long argument with the chief steward about responsibility and insurance went on far across the great black vacuum of India.

More thunderstorms fluttered in the foothills of the Himalayas while B.O.A.C. stuffed us once again, like Strasbourg geese, with food and drink. I had no idea what time it was or when I was going to get any sleep between these four- or five-hour leaps across the world. My watch said midnight G.M.T. and this tricked me into drinking a whisky and soda in the pretentious airport at New Delhi where the sad Benares brassware in unsaleable Indian shapes and sizes collects dust in the forlorn showcases. Alas, before I had finished it, a pale dawn was coming up and great flocks of awakened crows fled silently overhead towards some distant breakfast among the rubbish dumps outside India’s capital.

India has always depressed me. I can’t bear the universal dirt and squalor and the impression, false I am sure, that everyone is doing no work except living off his neighbour. And I am desolated by the outward manifestations of the two great Indian religions. Ignorant, narrow-minded, bigoted? Of course I am. But perhaps this extract from India’s leading newspaper, boxed and in heavy black type on the back page of the Statesman of November 21st, 1959, will help to excuse my prejudices:

10 YEARS’ PRISON FOR KIDNAPPING

New Delhi, Nov. 16

A bill providing deterrent punishment for kidnapping minors and maiming and employing them for begging, was introduced in the Lok Sabha today by the Home Minister, Pandit Pant.

The bill seeks to amend the relevant sections of the Indian Penal Code, and provides for imprisonment extending up to 10 years and fine in the case of kidnapping or obtaining custody of minors for employing them for begging, and life imprisonment and fine in the case of maiming. – P.T.I.

Back on the plane, the assistant stewardess wore the Siamese equivalent of a cheong sam. Five hours away was Bangkok. One rejected sleep and breakfast for the splendour below and away to port where the Himalayas shone proudly and the tooth of Everest looked small and easy to climb. Why had no one ever told me that the mouths of the Ganges are one of the wonders of the world? Gigantic brown meanderings between walls and islands of olive green, each one of a hundred tributaries seeming ten times the size of the Thames. A short neck of the Bay of Bengal and then down over the rice fields of Burma to the heavenly green pastures of Thailand, spread out among wandering rivers and arrow-straight canals like some enchanted garden. This was the first place of really startling beauty I had so far seen and the temperature of ninety-two degrees in the shade on the tarmac did nothing to spoil the impact of the country where I would advise other travellers to have their first view of the true Orient. The minute air hostess, smiling the first true smile, as opposed to an air-hostess smile, since London, told us to ‘forrow me’.

In spite of the mosquitoes as large as Messerschmitts and the wringing humidity, everyone seems to agree that Bangkok is a dream city, and I blamed myself for hurrying on to Hong Kong. In only one hour, one still got the impression of the topsy-turvy, childlike quality of the country and an old Siamese hand, a chance acquaintance, summed it up with a recent cutting from a Bangkok newspaper. This was a plaintive article by a high police official remonstrating with tourists for accosting girls in the streets. These street-walkers were unworthy representatives of Siamese womanhood. A tourist had only to call at the nearest police station to be given names and addresses and prices of not only the most beautiful, but the most respectable, girls in the city.

Back in the Comet that, after six thousand miles, seemed as fresh and trim as it had at London Airport, it was half an hour across the China Sea before one’s clothes came unstuck from one’s body. Then it was only another hour or so before the Chinese communist-owned outer islands of Hong Kong showed up below and we began to drift down to that last little strip of tarmac set in one of the most beautiful views in the world. It was nearly five o’clock and just over twenty-six hours and seven thousand miles from London. Twenty minutes late! Take a letter please, Miss Trueblood.

*

‘Is more better now, Master?’ I grunted luxuriously and the velvet hands withdrew from my shoulders. More Tiger Balm was applied to the finger tips and then the hands were back, now to massage the base of my neck with soft authority. Through the open french windows the song of bulbuls came from the big orchid tree covered with deep pink blossom and two Chinese magpies chattered in the grove of casuarina. Somewhere far away turtle doves were saying ‘coocoroo’. Number One Boy (Number One from among seven in the house) came in to say that breakfast was ready on the veranda. I exchanged compliments with the dimpling masseuse, put on a shirt and trousers and sandals and walked out into the spectacular, sun-drenched view.

As, half-way through the delicious scrambled eggs and bacon, a confiding butterfly, black and cream and dark blue, settled on my wrist, I reflected that heaven could wait. Here, on the green and scarcely inhabited slopes of Shek-O, above Big Wave Bay on the south-east corner of Hong Kong island, was good enough.

This was my first morning in Hong Kong and this small paradise was the house of friends, Mr and Mrs Hugh Barton. Hugh Barton is perhaps the most powerful surviving English taipan (big shot) in the Orient, and he lives in discreet accordance with his status as Chairman of Messrs Jardine Matheson, the great Far Eastern trading corporation founded by two energetic Scotsmen one hundred and forty years ago. They say in Hong Kong that power resides in the Jockey Club, Jardine Mathesons, the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank, and Her Majesty’s Government – in that order. Hugh Barton, being a steward of the Jockey Club, Chairman of Jardine’s, Deputy Chairman of the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank and a member of the Governor’s Legislative Council, has it every way, and when I complained of a mildly stiff neck after my flight it was natural that so powerful a taipan’s household should conjure up a comely masseuse before breakfast. That is the right way, but alas how rare, for powerful taipans to operate. When, the night before, I had complimented Mrs Barton for having fixed a supremely theatrical new moon for my arrival, I was not being all that fanciful.

Apart from being the last stronghold of feudal luxury in the world, Hong Kong is the most vivid and exciting city I have ever seen, and I recommend it without reserve to anyone who possesses the fate. It seems to have everything – modern comfort in a theatrically Oriental setting; an equable climate except during the monsoons; beautiful country for walking or riding; all sports, including the finest golf course – the Royal Hong Kong – in the East, the most expensively equipped racecourse, and wonderful skin-diving; exciting flora and fauna, including the celebrated butterflies of Hong Kong; and a cost of living that compares favourably with any other tourist city. Minor attractions include really good Western and Chinese restaurants, exotic night life, cigarettes at 1s. 3d. for twenty, and heavy Shantung silk suits, shirts, etc., expertly tailored in forty-eight hours.

With these and innumerable other advantages it is, therefore, not surprising that the population of this minute territory is over three million, or one million more than the whole of New Zealand. The fact that six hundred and fifty million communist Chinese are a few miles away across the frontier seems only to add zest to the excitement at all levels of life in the colony and, from the Governor down, if there is an underlying tension, there is certainly no dismay. Obviously China could take Hong Kong by a snap of its giant fingers, but China has shown no signs of wishing to do so, and when the remaining forty years of our lease of the mainland territory expire, I see no reason why a reduced population should not retreat to the islands and the original territory which we hold in perpetuity.

Whatever the future holds, there is no sign that a sinister, doom-fraught count-down is in progress. It is true that the colony every now and then gets the shivers, but when an American bank pulled up stumps during the Quemoy troubles in 1958, there was nothing but mockery. The government pressed on inside the leased territory with the building of the largest hospital in the Orient and with the erection of an average of two schools a month to meet the influx of refugees from China. The private Chinese and European builders also pressed on, and continue to press on today, with the construction of twenty-storey apartment houses for the lower and middle classes. Altogether it is a gay and splendid colony humming with vitality and progress, and pure joy to the senses and spirits.

Apart from my host, my guide, philosopher and friend in Hong Kong, and later in Japan, was ‘Our Man in the Orient’, Richard Hughes, Far Eastern correspondent of the Sunday Times. He is a giant Australian with a European mind and a quixotic view of the world exemplified by his founding of the Baritsu branch of the Baker Street Irregulars – Baritsu is Japanese for the national code of self-defence which includes judo, and is the only Japanese word known to have been used by Sherlock Holmes.

On my first evening he and I went out on the town.

The streets of Hong Kong are the most enchanting night streets I have trod. Here the advertising agencies are ignorant of the drab fact, known all too well in London and New York, that patterns of black and red and yellow have the most compelling impact on the human eye. Avoiding harsh primary colours, the streets of Hong Kong are evidence that neon lighting need not be hideous, and the crowded Chinese ideograms in pale violet and pink and green with a plentiful use of white are entrancing not only for their colours but also because one does not know what drab messages and exhortations they spell out. The smell of the streets is sea-clean with an occasional exciting dash of sandalwood from a joss-stick factory, frying onions, and the scent of sweet perspiration that underlies Chinese cooking. The girls, thanks to the cheong sams they wear, have a deft and coltish prettiness which sends Western women into paroxysms of envy. The high, rather stiff collar of the cheong sam gives authority and poise to the head and shoulders, and the flirtatious slits from the hem of the dress upwards, as high as the beauty of the leg will allow, demonstrate that the sex appeal of the inside of a woman’s knee has apparently never occurred to Dior or Balmain. No doubt there are fat or dumpy Chinese women in Hong Kong, but I never saw one. Even the men, in their spotless white shirts and dark trousers, seem to have better, fitter figures than we in the West, and the children are a constant enchantment.

We started off our evening at the solidest bar in Hong Kong – the sort of place that Hemingway liked to write about, lined with ships’ badges and other trophies, with, over the bar, a stuffed alligator with an iguana riding on its back. The bar belongs to Jack Conder, a former Shanghai municipal policeman and reputed to have been the best pistol shot there in the old days. His huge fists seem to hold the memory of many a recalcitrant chin. He will not allow women in the bar downstairs on the grounds that real men should be allowed to drink alone. When the Japanese came in 1941, Conder stayed on in Shanghai, was captured and escaped. He took the long walk all the way down China to Chungking, sleeping during daylight hours in graveyards, where the ghosts effectively protected him. He is the authentic Hemingway type and he sells solid drinks at reasonable prices. His bar is the meeting place of ‘Alcoholics Synonymous’ – a group of lesser Hemingway characters, most of them local press correspondents. The initiation ceremony requires the consumption of sixteen San Migs, which is the pro name for the local San Miguel beer – to my taste a very unencouraging brew.

After fortification with Western poisons (I gather that no self-respecting Chinese would think of drinking before dinner, but that the fashion for whisky is invading the Orient almost as fast as it has invaded France) we proceeded to one of the finest Chinese locales, the Peking Restaurant. Dick Hughes, a hard-bitten Orientalogue, was determined that I should become Easternized as soon as possible and he missed no opportunity to achieve the conversion. The Peking Restaurant was bright and clean. We consumed seriatim:

shark’s fin soup with crab,

shrimp balls in oil,

bamboo shoots with seaweed,

chicken and walnuts,

with, as a main dish,

roast Peking duckling,

washed down with mulled wine. Lotus seeds in syrup added a final gracious touch.

Dick insisted that then, and on all future occasions when we were together, I should eat with chopsticks, and I pecked around with these graceful but ridiculous instruments with clumsy enthusiasm. To my surprise the meal, most elegantly presented and served, was in every respect delicious. All the tastes were new and elusive, but I was particularly struck with another aspect of Oriental cuisine – each dish had a quality of gaiety about it, assisted by discreet ornamentation, so that the basically unattractive process of shovelling food into one’s mouth achieved, whether one liked it or not, a kind of elegance. And the background to this, and to all my subsequent meals in the East, always had this quality of gaiety – people chattering happily and smiling with pleasure and encouragement. From now on, all the meals I ate in authentic, as opposed to tourist, Chinese or Japanese restaurants were infinitely removed from what, for a lifetime, had been a dull, rather unattractive routine in the sombre eating-mills of the West, where the customer, his neighbours and the waiters seem subtly to resent each other, the fact that they should all be there together, and very often the things they are eating.

Dick Hughes spiced our banquet with the underground and underworld gossip of the colony – the inability of the government to deal drastically with Hong Kong’s only real problem, the water shortage. Why didn’t they hand it over to private enterprise? The gas and electricity services were splendidly run by the Kadoorie brothers, whose record had been equally honourable in Shanghai. There was a grave shortage of hotels. Why didn’t Jardines do something about it? Japanese mistresses were preferable to Chinese girls. If, for one reason or another, you fell out with your Japanese girl, she would be dignified, philosophical. But the Chinese girl would throw endless hysterical scenes, and probably turn up at your office and complain to your employer. Servants? They were plentiful and wonderful, but too many of the English and American wives had no idea how to treat good servants. They would clap their hands and shout ‘Boy!’ to cover their lack of self-confidence. This sort of behaviour was out of fashion and brought the Westerner into disrepute. (How often one has heard the same thing said of English wives in other ‘coloured’ countries!)

The latest public scandal was the massage parlours and the blue cinemas (with colour and sound!) that flourished, particularly across the harbour in Kowloon. The Hong Kong Standard had been trying to clean them up. The details they had published had anyway been good for circulation. He read out from the Standard: ‘Erotic dailies circulate freely here. Blue films shown openly. Hong Kong police round up massage girls.’ The Standard had given the names and addresses: ‘Miss Ten Thousand Fun and Safety at 23 Stanley Street, 2nd floor. Business starting at 9 a.m. . . . Miss Soft and Warm Village . . . Miss Outer Space, and Miss Lotus of Love at 17 Cafe Apartments, Room 113, ground floor. (Opposite the French Hospital. Room heated) . . . Miss Chaste and Refined, Flat A, Percival Mansion, 6th floor (lift service).’ And more wonderful names: ‘Miss Smooth and Fragrant . . . Miss Emerald Parsley . . . Miss Peach Stream Pool (satisfaction guaranteed),’ and so forth.

The trouble, explained Dick, was partly the traditional desire of Oriental womanhood to please, combined with unemployment and the rising cost of living. Increase in the number of light industries, particularly the textile mills, the bane of Lancashire and America, might help. Would I like to visit the latest textile mill? I said I wouldn’t.

It was a natural step from this conversation to proceed from the Peking Restaurant to the world of Suzie Wong.

Richard Mason, with his splendid book The World of Suzie Wong, has done for a modest waterfront hotel what Hemingway did for his very different Harry’s Bar in Venice. The book, though, like A Many-Splendoured Thing by Han Suyin, read universally by the literate in Hong Kong, is small-mindedly frowned upon, largely I gather because miscegenation with beautiful Chinese girls is understandably an unpopular topic with the great union of British womanhood. But the Suzie Wong myth is in Hong Kong to stay, and Richard Mason would be amused to find how it has gathered depth and detail.

It seems to be fact, for instance, and perhaps the only known fact, that when he was in Hong Kong Richard Mason did live in a waterfront establishment called the Luk Kwok Hotel, transformed in his book into the Nam Kok House of Pleasure, where the painter, Robert Lomax, befriended and, after comic, tender, romantic and finally tragic interludes, married the charming prostitute Suzie Wong.

As a result of the book, the Luk Kwok Hotel, so conveniently placed near the Fleet landing stage and the British Sailors’ Home, has boomed. Solitary girls may still not sit unaccompanied in the spacious bar with its great and many-splendoured jukebox. You must still bring them in from outside, as did Lomax, to prevent the hotel becoming, legally, a disorderly house. But the whole place has been redecorated in deep battleship grey (to remind the sailors of home?) and one of Messrs Collins’s posters advertising Richard Mason’s book has a place of honour on the main wall. Other signs of prosperity are a huge and hideous near-Braque on another wall, a smart Anglepoise light over the cash register, and a large bowl of Siamese fighting fish. (It is also a sign of fame, of which the proprietor is very proud, that the totally respectable Prime Minister of Laos and his Foreign Minister stayed at the Luk Kwok on a visit to Hong Kong.) If you inquire after Suzie herself, you are answered with a melancholy shake of the head and the sad, dramatic news that Suzie’s marriage failed and she is now back ‘on the pipe’. When you ask where you could find her, it is explained that she will see no other man and waits for Lomax one day to return. She is not in too bad a way, as Lomax sends her regular remittances from London. But there are many other beautiful girls here just as beautiful as Suzie. Would you care to meet one, a very particular friend of Suzie’s?

I don’t know how much the sailors believe this story, but I suspect they are all quite happy to put up with ‘Suzie’s friend’, and I for one greatly enjoyed exploring the myth that will forever inhabit the Luk Kwok Hotel with its neon slogans: ‘GIRLS, BUT NO OBLIGATION TO BUY DRINKS! CLEAN SURROUNDINGS! ENJOY TO THE MAXIMUM AT THE LEAST EXPENSE!’

Dick Hughes misunderstood one author’s delighted interest in the brilliance of another author’s myth, and protested that there were far better establishments awaiting my patronage. But by now it was late and the after-effects of jet travel – a dull headache and a bronchial breathlessness – had caught up with me, and we ended our evening with a walk along the thronged quays in search of a taxi and home.

On the way I commented on the fact that there is not a single seagull in the whole vast expanse of Hong Kong harbour. Dick waved towards the dense flood of junks and sampans on which families of up to half a dozen spend the whole of their lives, mostly tied up in harbour. There hadn’t used to be any seagulls in Shanghai either, he said. Since the communists took over they have come back. The communists have put it about that they had come back because they no longer have to fight with the humans for the harbour refuse. It was probably the same thing in Hong Kong. It would taken an awful lot of seagulls to compete for a living with three million Chinese.

On this downbeat note I closed my first enchanted day.

INCIDENTAL INTELLIGENCE

Hotels

By tradition and probably correctly, the Peninsula (the ‘Pen’), on the Kowloon peninsula, is regarded as the Number 1 hotel for visitors to the colony. It now has an annexe, Peninsula Court. Rates are from HK$70 (single) to HK$100 (double). Very colonial, comfortable, proper. It is generally booked fully for months in advance. Next come the Miramar (behind the Peninsula geographically, but livelier and overtaking it by enterprise and expansion) and the Gloucester (on the island). Miramar rates range from HK$36 to 75; the Gloucester, HK$40 to 75.

If you are holidaying, the Repulse Bay Hotel, across the island and fronting a reasonable beach, is recommended. (HK$30 to 95.) This is set in lovely gardens and the local beauties, wives and concubines offer a dazzling display at the Sunday afternoon tea-dances. The food is better than at the Peninsula or the Miramar. But it takes half an hour to cross the island to the business, shopping and social centre of Hong Kong (officially called Victoria).

The Luk Kwok, Suzie Wong’s original official address, encourages a livelier clientele. Single room (an interesting aspiration), HK$11; double (virtually de rigueur), up to HK$35.

(For comparison, a Chinese can get a bed of a sort in a wooden hut or ‘garage’, shared with half a dozen companions, in the industrial areas for HK$8 (10s.) a month.)

Eating

For Western food, the Marco Polo in the Peninsula Court is the most expensive restaurant and can sometimes be the best. Gaddi’s, off the Peninsula ground-floor marble lobby, is also recommended. On the island, the Parisian Grill (the ‘P.G.’) is the oldest and best-known restaurant, jam-packed at lunch; but standards and prices at Jimmy’s Kitchen and the Gloucester (now operating a rejuvenated kitchen) are roughly equivalent. Maxim’s and the Café de Paris charge slightly more. More Chinese go to Maxim’s than to the ‘P.G.’, and there is dancing in the evening; Hong Kong’s feminine elegance glitters at Maxim’s at the cocktail hour. You can get bear’s paw – overrated – at the Gloucester. (N.B. The best and biggest martinis in the colony are served in the Mexican bar in the Gloucester.)

All visitors want to eat on the floating restaurants at Aberdeen. As this venture involves a forty-minute taxi haul from Victoria, the earnest diner might care to break his journey at the Repulse Bay Hotel and brace himself with a few shots on the veranda around sunset before tackling the next fifteen minute stage to reach the floating restaurants at twilight.

Dinner at the Carlton, four miles out of Kowloon on the main road to the New Territories, unfolds one of the world’s most memorable panoramas: the jewelled lights of Kowloon, the harbour and the island.

Chinese food

The range and quality of Chinese cuisine in Hong Kong are matched only in Taipeh. Beggar’s chicken at the Tien Hong Lau in Kowloon is incomparable; if possible, it should be ordered the day before. Peking duck is the speciality of the Princess Garden in Kowloon and the Peking Restaurant on the island. The Ivy (on the island) serves exotic Szechuanese-style food. The Café de Chine serves Cantonese-style dishes in two huge connecting dining-rooms on the top floor of a ten-storey building in the heart of Victoria. A regular wealthy Chinese visitor from San Francisco always goes to the Tai Tung for one special dish which he claims is unequalled anywhere else: roast sucking pig à la Cantonese. Everyone has his favourite. You can feast cheaply at the lot.

Night Life

Generally, night life in Hong Kong is much as anywhere else. There are twenty-five registered night-clubs, some of which tolerate second-rate floor shows on the dreary Asian circuit (Singapore – Kuala Lumpur – Bangkok – Hong Kong – Manila – Tokyo). None are in the same class as the Tokyo night-clubs, and chauvinistic Hong Kong apologists, with desperate parochialism, are compelled to find compensation in the proud boast that the local night-clubs don’t close until two a.m., while the lights go out reluctantly in the Tokyo cabarets (but not the bars) at midnight.

The dance-hostesses are on call which does not mean by telephone, but by personal arrangement at seventy-six ‘ballrooms’. The prettiest girls and the best bands tend to be in places like the Tonnochy Ballroom and the Golden Phoenix (on the island) and at the Oriental (in Kowloon), where most of the patrons are Chinese and no hard liquor is served, only tea, soft drinks and melon seeds.

There are 8,000 registered hostesses, whose company (financed by a coupon system) ranges from 60 cents to HK$5.50 per twenty minutes. At the Tonnochy or the Metropole (where you should ask to study the telephone-directory-like album, which shows the photographs and names of available hostesses), an hour’s dancing will thus cost HK$16.50 (just over £1). Most of the girls in the higher-priced ballrooms are glamorous and Englishspeaking and, subject to financial adjustment with the proprietor, will gladly leave the ballroom and accompany a visitor to a night-club; this invitation, of course, gives them great face. The tourist has the patriotic satisfaction of knowing that the colony’s government collects ten per cent tax on every dance-girl’s coupons.

There are scores of brash and noisy bars along Lockhart Street and in Wanchai and North Point (on the island) and throughout the back lanes of Kowloon, some of which, when the navies are in port, are a dim echo of Shanghai’s old Blood Alley.

Although not featured in the prim official tourist handbooks, small sampans at Causeway Bay (on the island) offer a mild variation of the old Shanghai and Canton flower-boat entertainment as once available in the dear dead days before the coming of Mao Tse-Tung. A curtain gives the passengers privacy from the pilot, and the sampan either drifts with wind and current in seclusion, or moves, as desired, to floating markets and teashops and rafts of singers and musicians. (Tariff: about HK$1 an hour or up to HK$10 for the night.)

2

Macao

Gold, hand in hand with opium, plays an extraordinary secret role through the Far East, and Hong Kong and Macao, the tiny Portuguese possession only forty miles away, are the hub of the whole underground traffic.

In England, except between bullion brokers, nobody ever talks about gold as a medium of exchange or as an important item among personal possessions. But from India eastwards gold is a constant topic of conversation, and the daily newspapers are never without their list of gold prices in bullion, English sovereigns, French Napoléons and louis d’or, and rarely a day goes by without there being a gold case in the Press. Someone has been caught smuggling gold. So-and-so has been murdered for his gold hoard. Someone else has been counterfeiting gold. The reason for this passionate awareness of the metal is the total mistrust all Orientals have for paper money and the profound belief that, without one’s bar or beaten leaf of gold concealed somewhere on one’s person or kept in a secret place at home, one is a poor man.

The gold king of the Orient is the enigmatic Doctor Lobo of the Villa Verde in Macao. Irresistibly attracted, I gravitated towards him, the internal Geiger-counter of a writer of thrillers ticking furiously.

Richard Hughes and I took the S.S. Takshing, one of the three famous ferries that do the Macao run every day. These ferries are not the broken-down, smoke-billowing rattletraps engineered by whisky-sodden Scotsmen we see on the films, but commodious three-decker steamers run with workmanlike precision. The three-hour trip through the islands and across Deep Bay, brown with the waters of the Pearl River that more or less marks the boundary between the leased territories and Communist China, was beautiful and uneventful. The communist gunboats have given up molesting Western shipping and the wallowing sampans chugging with their single diesels homewards with the day’s catch, the red flag streaming from the insect-wing sails, were the only sign that we were crossing communist waters. At the northern extremity of Deep Bay lies Macao, a peninsula about one-tenth the size of the Isle of Wight that is the oldest European settlement in China. It was founded in 1557 and is chiefly famous for the first lighthouse built on the whole coast of China. It also boasts the graves of Robert Morrison, the Protestant missionary who compiled the first Chinese–English dictionary in 1820, of George Chinnery, the great Irish painter of the Oriental scene, and of the uncle of Sir Winston Churchill, Lord John Spencer Churchill. It is also noted for the gigantic ruins of St Paul’s Cathedral built in 1602 and burned down in 1835; and finally – save the mark! – for the largest ‘house of ill-fame’ in the world.

So far as its premier citizen, Dr Lobo, is concerned, the most interesting features of Macao are that there is no income tax and no exchange control whatever, and that there is complete freedom of import and export of foreign currencies; and all forms of bullion. To take only the case of gold bullion, it is, therefore, perfectly easy for anyone to arrive by ferry or seaplane or come across from Communist China, only fifty yards away across the river, buy any quantity of gold, from a ton down to a gold coin, and leave Macao quite openly with his booty. It is then up to the purchaser, and of no concern whatsoever to Dr Lobo or the chief of the Macao police, to smuggle his gold back into China, into neighbouring Hong Kong or, if he has a seaplane, fly off with it into the wide world. These considerations make Macao one of the most interesting marketplaces in the world, and one with many secrets.

As we came into the roadstead, we were greeted by a scene of great splendour. The sun was setting and in its pathway lay a spectacular fleet of many hundreds of junks and sampans at anchor. This caused much excited chattering amongst our fellow-passengers and it was only on the next morning, when this fleet and other fleets from the outer islands were spread all over the sea, now under the rising