11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

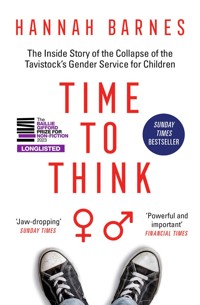

- Herausgeber: Swift Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

SHORTLISTED FOR THE BAILLIE GIFFORD PRIZE FOR NON-FICTION SHORTLISTED FOR THE ORWELL PRIZE FOR POLITICAL WRITING 'This is what journalism is for' - Observer Time to Think goes behind the headlines to reveal the truth about the NHS's flagship gender service for children. The Tavistock's Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) was set up initially to provide talking therapies to young people who were questioning their gender identity. But in the last decade GIDS referred around two thousand children, some as young as nine years old, for medication to block their puberty. In the same period, the number of referrals exploded and the profile of the patients changed: from largely pre-pubescent boys to mostly adolescent girls, who were often contending with other difficulties. Was there enough clinical evidence to justify such profound medical interventions? This urgent, scrupulous and dramatic book explains how GIDS has been the site of a serious medical scandal, in which ideological concerns took priority over clinical practice.It is a disturbing and gripping parable for our times.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 917

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Book of the Year in The Economistand The Times/Sunday Times

Shortlisted for the Baillie Gifford Prize for Non-Fiction and the Orwell Prize for Political Writing

‘A deeply reported, scrupulously non-judgmental account of the collapse of the NHS service, based on hundreds of hours of interviews with former clinicians and patients. It is also a jaw-dropping insight into failure: failure of leadership, of child safeguarding and of the NHS’

Sunday Times

‘An exemplary and detailed analysis of a place whose doctors, Barnes writes, most commonly describe it as “mad”. This is a powerful and disturbing book’

Financial Times

‘Meticulous and scrupulously researched book on GIDS’ downfall’

Guardian

‘This book is a testament to the moral courage of Hutchinson and colleagues who sought to expose the chaos and insanity they saw while practising by stealth the in-depth therapy they believed young people deserved… And Hannah Barnes has honoured them with her dogged, irreproachable yet gripping account’

The Times

‘Barnes has managed the impossible: to write a book with clinical precision about the most ideologically and emotionally charged subject in Britain today. It is a tale of organisational failure, punctuated by the bravery of whistleblowing clinicians and the raw testimonies of former patients. Everyone should take the time to read Time to Think’

Daily Mail

‘This incredibly important book shows that we still don’t know how many children were damaged for life. I want every institution and every politician who pontificates about gender to read this book and ask what happened to all those lost girls and boys – and why they were complicit’

Daily Telegraph

‘A jaw-dropping piece of investigative journalism… much wiser to read Barnes’s book than trashy diaries and insider Westminster revelations, it seems to me, if you want to get a handle on how Britain works (or doesn’t)’

Justin Webb, Independent Best Summer Books 2023

‘A brilliant book written in a very thoughtful way about the failures of the Tavistock clinic’

Wes Streeting

‘Hannah Barnes’s scrupulous research is a painful, important reminder that clinical care that promotes the wellbeing of young people experiencing gender incongruence and distress, and that protects their autonomy, cannot be built on ideological sands of ignorance, forgetting and silencing’

TLS

‘Hannah Barnes steadfastly refuses to enter into the Manichean ideological debates and culture wars around gender identity. Instead she unearths the facts to present an alarming story of medical scandal’

Baillie Gifford Prize judges’ comment

‘As scrupulous as journalism can be… nuanced, ambiguous and, sadly, often disturbing’

New Statesman

‘A journalistic and sobering take on a divisive subject’

The Economist Best Books of 2023

‘Through interviews with patients and clinicians, she compiles a portrait of an institution in thrall to ideology: in consequence children were subjected to treatments that changed their bodies while their mental health was neglected. An essential account of the corrosive influence of passionate intensity on medicine, and all the more shocking for being written in cool, compassionate prose’

Sarah Ditum, Sunday Times Critics’ Books of the Year

‘Dynamite… The revelations it contains are horrifying: former clinicians at GIDS detail how some children were placed on medication after one face-to-face assessment, despite many having mental health or family issues. More than a third of young people referred to the service had moderate to severe autistic traits, compared with under 2 per cent of children in the general population… The resulting scandal is now plain to see: children damaged for life having been placed on medication that should not have been given to them’

The Spectator

‘What happened [at GIDS], and how it went so appallingly wrong, is now the subject of a remarkable book by the journalist Hannah Barnes’

UnHerd

‘Forensic… Over a decade, the Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) based at Tavistock has referred more than 1,000 children, some as young as nine years of age, for medication to block their puberty, despite the lack of a clear evidence base for the off-label use of these drugs and the developing concerns of many staff… At the end of this investigation into Tavistock, the psychologist interviewed by Barnes is certain the service has been hurting children, but has a new question – “How many?”’

Irish Times

‘Barnes’s compelling account of the downfall of GIDS demonstrates how pressure groups can lead well-meaning clinicians to make increasingly ill-advised decisions. Time to Think is a devastating and shocking read, a salutary tale that shows how medical scandals can happen in plain sight and complaints are ignored when nobody is quite sure about their actual position on the issue’

Sunday Independent, Ireland

‘For anyone with an interest in the vexed history of treatment of gender dysphoria in children as well as the wider issue of young people’s mental health, this compelling account of how NHS services faltered under the strain of meeting their needs is well worth reading’

Morning Star

‘What [the treatment of gender dysphoria] requires is cool heads, honesty, the accumulation of sound empirical evidence, and a willingness to acknowledge that adolescence is a period of turmoil, and that children caught up in its buffeting are not always best placed to make life-changing decisions about their futures. It is to Barnes’ great credit that, in spite of the fear and timidity of publishers and the accusations of activists, she was prepared to give voice to the professionals who have not been allowed to make that case’

New Zealand Listener, Best Books of 2023

‘Despite her meticulous work and the clear public interest, it was difficult to find a publisher willing to take it on – none of the big publishing houses would touch it… But the power of the book is that she doesn’t rely on activists or fringe observers with an ideological bent. Well-meaning but often overwhelmed GIDS clinicians spoke to her of their regret in referring young people for puberty-blocking and cross-hormone treatment without solid data to support this pathway and in the absence of broader mental health assessments’

The Australian

‘Most journalists avoid this controversial topic for fear of backlash, but BBC journalist Hannah Barnes courageously dove into the research – gaining access to thousands of pages of documents, including unpublished reports. The result is a thoroughly researched exposé about what happens when politics and ideology take over medicine’

Free Press, Best Books of 2023

‘The question Barnes puts at the centre of this book is “Are we hurting children?” What follows is an extraordinarily sensitive and important piece of work that exposes the huge price some of our young have had to pay for a system that was simply not rigorous enough in asking that question’

Emily Maitlis

Contents

PrefaceAuthor’s NoteGender Identity Development Service (GIDS) Timeline1 ‘Are we hurting children?’ 2 The Vision Ellie3 The Push for Puberty Blockers Phoebe4 Early Intervention Jack5 A New Era Diana and Alex6 All Change 7 The Bombshell 8 How to Cope 9 Speed in Leeds Hannah10 Raising Concerns 11 Scapegoats and Troublemakers 12 The Bell Report 13 Bell: The Aftermath 14 First Fears Jacob15 200 Miles up the M1… 16 Across the Sea 17 The GIDS Review and Outside Scrutiny 18 Regret and Redress 19 Data and ‘Disproportionate effort’ Harriet20 When in Doubt, Do the Right Thing 21 An Uncertain Future ConclusionEpilogue: History Doesn’t Repeat Itself, But It Often RhymesAcknowledgementsNotesFor my wonderful girls, who amaze me every day. I’m so proud to be your Mum.And for Pat, the most patient man on Earth.

Preface

When I set out to write this book, I wanted to create a lasting historical record of what has taken place in this under-researched and – for many years – unscrutinised area of healthcare. I believed that only by learning from what has happened in the past can improvements be made to care in the future.

It was only after Swift Press had taken the project on and writing was well underway that it began to seem as if, in England at least, the story might well be heading towards its final act. The interim report of an official, independent and exceptionally thorough review of youth gender identity services had concluded that a fundamentally different model of care was needed – one that took into account all aspects of young people’s lives and pasts, not just their gender identity difficulties. And just a few months later, in the summer of 2022, NHS England announced its intention to close the Tavistock and Portman’s Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) and replace it with new regional services that would follow that very different model.

But, as I wrote in the book’s original conclusion, ‘This is a story that is yet to end.’ And, in the year or so since those words were first published, it is increasingly clear that the story has still not ended. It has taken on new twists and turns, repeating some of the mistakes of the past, and adding new difficulties along the way. So I have updated the text and written a new epilogue, to bring things as up to date as I can.

Despite the intention that GIDS would be closed by the spring of 2023, in early 2024 it was still open, and still operating according to a model of care that has been found seriously wanting. Since NHS England announced its intention to close the service, GIDS clinicians have referred at least another 120 children to endocrinologists at University College London Hospitals (UCLH) and Leeds Teaching Hospitals, with the number increasing every month. These referrals have been made despite the fact that the evidence base underpinning the use of puberty blockers has been judged to be of very low certainty, and despite NHS England’s intention that they should only be prescribed as part of a clinical trial. In total, since these drugs became more widely available to children and young people in the UK, my best estimate is that around 2,000 under-18s have been referred. The vast majority of those will have gone on to receive regular injections of the blockers, most likely then followed by cross-sex hormones, and possibly surgery in adult services.

The delay in the closure has been down to the difficulties faced in setting up the new services that will replace GIDS. The spring 2023 deadline came and went, and so did a second one set for autumn. It was never going to be an easy task, but in the new epilogue written for this paperback edition I set out why the attempt made by the world-famous children’s hospital Great Ormond Street merely to provide the training materials for the new services was destined to fail. And I explore the consequences of this failure as GIDS remained open and the private sector saw an opportunity to meet ever-growing demand. Sharp, irreconcilable differences between health professionals in England remain, and there is a growing chasm between the medical approaches taken in an increasing number of European countries and those adopted in the United States and Canada. All the while, the holes in the evidence base underpinning the use of puberty blockers and hormones in children remain unplugged, and the list of questions surrounding their use grows longer.

It may well be that by the time you are reading this, events will have moved on further: GIDS will finally close its doors on 31 March 2024, followed by the opening, in some form, of two regional services. Dr Hilary Cass’s long-awaited final report and recommendations on youth gender identity services should also have been published. With that report’s publication there will be an opportunity to change the way young people with gender identity difficulties are cared for, to make sure treatment is individualised and evidence-based, and that it is not rushed. It will take a determination that has hitherto been lacking from NHS England to ensure those recommendations are followed closely. But even then, the fact that so many did so little, for so long, has meant there is a mountain to climb. With private providers and some GPs stepping in to fill a gap in care available on the NHS, and a waiting list of 6,000 young people – and growing – there will be no quick fixes. The story continues.

Hannah BarnesLondon, January 2024

Author’s Note

This book is based on the experiences of clinicians who have worked directly with several thousands of young people experiencing gender-related distress or questioning their gender identity. Their time at the Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) spans more than two decades, across multiple cities. Many have not worked alongside each other, nor ever met. They are male and female, gay and straight, newly qualified and hugely experienced. Some worked at the service for a matter of months, some years, and some many years. By training they are psychologists, psychotherapists, social workers, family therapists and nurses. They are all conscientious professionals, trying to do their best for their patients.

I contacted close to 60 clinicians who have worked at GIDS in an attempt to hear as broad a range of voices as possible. Many agreed to speak to me and share their thoughts and experiences of their work. A number have spoken on the record and are named; others have spoken on the condition of anonymity, or to help inform my writing only. Where names have been changed this is indicated, but all quotations are real and accurate, recorded verbatim.

A number of governors responsible for ensuring that the NHS Trust that houses GIDS is well run have also spoken with me, along with senior clinicians working elsewhere in the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust.

Where allegations cannot be attributed to named individuals in order to protect their anonymity, they have been double-sourced at a minimum and a right-of-reply has been given. Testimony is supported by several thousand pages of internal documentation relating to the service, alongside official reports, academic papers and legal judgments. I have also read every published Freedom of Information request relating to GIDS, as well as making some of my own.

Former GIDS service users who are identified have given permission to be so, while others have had their names changed to protect their privacy. All have provided documentation from their time at GIDS, and I am hugely grateful to them for trusting me with their stories, sharing with me their experiences and, in some instances, highly personal and sensitive information. Where clinicians have discussed clinical examples with me, all identifying information has been changed to protect patient confidentiality. I have not been privy to any identifying clinical data beyond that shared with me by the young people themselves.

Everyone interviewed for this book has either: direct experience of GIDS as a member of staff, a service user or the parent of one; raised concerns about GIDS from within the Tavistock and Portman Trust; sought to improve the service in their capacity as a governor for the Trust; or been directly involved in legal action involving GIDS.

I have conducted well over a hundred hours of interviews.

This is an area of healthcare and wider society where language is often disputed. Words and terms that are accepted at one time become outdated or even offensive at another. I have tried to use the language that was in place at the time of events being written about, and the terminology used by my contributors. I respect people’s chosen pronouns throughout. I use the words ‘boy’ and ‘girl’ throughout to mean those who are at birth biologically male and those biologically female, respectively. I do this not to cause any offence to those who choose to transition, but to aid clarity.

All but two of the scores of interviews that form the basis of this book were completed before the decision to close GIDS was taken. These clinicians and former service users did not know what steps NHS England would take when they agreed to speak to me. It is a story that has been constantly evolving while I have been writing, and one in which there are, no doubt, more changes to come.

Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) Timeline

1989 The Gender Identity Development Clinic opens at St George’s Hospital, south London, under the leadership of Dr Domenico Di Ceglie.

1994 The service moves to the Tavistock and Portman Trust, north London.

May–October 2005 Dr David Taylor, medical director of the Trust, conducts a review of GIDS after concerns are raised by staff.

January 2006 Taylor’s report makes a series of recommendations to strengthen the care provided.

2009 GIDS is nationally commissioned by the NHS, and Dr Polly Carmichael replaces Domenico Di Ceglie as director of the service.

February 2011 A joint team from GIDS and University College London Hospitals (UCLH) gain ethical approval for an ‘Early Intervention Study’ to evaluate the impact of early pubertal suppression in a selected group of young people.

2012 GIDS opens a second base in Leeds.

April 2014 GIDS rolls out ‘early intervention’ across the service. The study’s lower age limit of 12 is removed as the clinic moves to a ‘stage’ not ‘age’ approach, allowing younger children to be referred for puberty blockers.

October 2015 As referrals rise exponentially, the GIDS leadership commission external consultant Femi Nzegwu to advise on working practices. She recommends GIDS ‘take the courageous and realistic action of capping the number of referrals immediately’.

August 2018 Dr David Bell presents the Tavistock board with a report, detailing the concerns of ten GIDS staff who have shared their worries with him as staff governor. He brands GIDS ‘not fit for purpose’.

February 2019 Commissioned by the Trust to investigate the concerns raised by Bell, medical director Dr Dinesh Sinha’s GIDS Review is published. The Trust says it does not identify ‘any immediate issues in relation to patient safety or failings in the overall approach taken by the Service’.

September 2020 NHS England commissions paediatrician Dr Hilary Cass to conduct an independent review into gender identity services for children and young people.

December 2020 The High Court rules that it is ‘unlikely’ that under-16s can give informed consent to treatment with puberty blockers.

January 2021 A further report into safeguarding concerns raised by GIDS clinician Helen Roberts is submitted to senior Trust staff.

Healthcare regulator the Care Quality Commission (CQC) rates GIDS ‘Inadequate’, its lowest possible rating.

February 2021 The results of the Early Intervention Study are formally published. The research team ‘identified no changes in psychological function, quality of life or degree of gender dysphoria’ in the young people prescribed puberty blockers.

September 2021 The Central London Employment Tribunal rules that Tavistock children’s safeguarding lead, Sonia Appleby, had been vilified by the Trust because she raised safeguarding concerns about GIDS.

The Court of Appeal overturns the High Court’s judgment, saying that it is for doctors, not the courts, to decide on the capacity of young people to consent to medical treatment.

March 2022 Dr Hilary Cass’s interim report is published, which argues that GIDS’s ‘single specialist provider model is not a safe or viable long-term option’ for the care of young people experiencing gender incongruence or gender-related distress.

July 2022 NHS England announce that GIDS will be closed and replaced by regional centres at existing children’s hospitals, with a greater focus on mental health.

Spring 2023 The target for closing GIDS and opening the first of two new regional youth gender identity services is missed.

September 2023 A reanalysis of data from GIDS’s landmark Early Intervention Study shows that, contrary to the researchers’ original conclusion that participants experienced ‘no changes in psychological function’, when individual trajectories were looked at, the majority experienced a significant impact on their mental health, for better and worse.

December 2023 Responsibility for training and developing educational materials for staff employed by the new regional gender identity services is taken away from Great Ormond Street Hospital by NHS England and handed to the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges.

March 2024 The Gender Identity Development Service at the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust closes, ending its 35-year history.

1

‘Are we hurting children?’

February 2017

Dr Hutchinson was seriously concerned. ‘Are we hurting children?’ she asked, keen to be reassured. It’s the question that underpins everything she’s feeling.

She was not told ‘no’.

Anna Hutchinson, a senior clinical psychologist at the Gender Identity Development Service (known to everyone as GIDS), cared deeply for the hundreds of children seeking her help. They felt that the bodies they had been born with didn’t match their gender identity, and many were deeply distressed. But she was desperately worried about whether the treatment GIDS could help them access – a referral for powerful drugs and the beginning of a medical pathway to physical gender transition – was ethical. Could it really be the best and only approach for all the young people in her care?

Hutchinson had witnessed an explosion in the number of young people seeking help from GIDS. Since 2007 it had grown from a small team that saw 50 young people each year to a nationally commissioned service treating thousands.1 In the four years she had been there alone, the number of children referred had risen from 314 to 2,016.2 But it wasn’t just the numbers. The existing evidence base which supported the use of puberty blockers for young people was not just limited: it didn’t seem to apply to the children being referred to GIDS. Whereas most of the literature on gender non-conforming children was about boys who had a lifelong sense of gender incongruence, GIDS’s waiting room was overpopulated with teenage girls whose distress around their gender had only started in adolescence. Many of them were same-sex attracted – the same was true for the boys attending GIDS – and many were autistic. Their lives were complicated too. So many seemed to have other difficulties – eating disorders, self-harm, depression – or had suffered abuse or trauma. How could such different lives and presentations lead to the same answer – puberty blockers?

Dr Sarah Davidson, one of three highly experienced consultant psychologists leading the service, sat directly opposite Hutchinson in Davidson’s third-floor office at the Tavistock Centre, north London. She was unable to reassure her colleague.

Their conversation was part of regular clinical supervision, during which psychologists share thoughts on clinical cases currently under their care. Over the preceding few years, these meetings had grown gradually more intense, says Hutchinson. But whenever she and Davidson came close to discussing the thorniest questions, the discussion would be derailed.

Their last supervision session of 2016 had ended badly. So much so that Dr Davidson apologised afterwards that the discussions had fallen into an ‘unhelpful pattern’.3 She, like the service as a whole, was under immense pressure. It couldn’t cope with the rapidly increasing referrals and was doing its best to keep an ever-expanding waiting list under control. Hutchinson admired her supervisor. She wanted advice on the extremely complex cases that were now presenting at GIDS, and how to act in the best interests of these children.

As a member of the GIDS senior team, Hutchinson had been privy to major decisions. But she felt increasingly uncomfortable. Alongside the dramatically changed patient population, puberty blockers, she felt, were not behaving as staff had initially believed them to. Evidence from within GIDS showed blockers weren’t providing time and space to think and reflect as they had been told, and as they had been telling children and their families. Some young people’s health appeared to deteriorate while on the medication. And yet almost no one stopped the treatment. Hutchinson felt she was part of a service ‘routinely offering an extreme medical intervention as the first-line treatment to hundreds of distressed young people who may or may not turn out to be “trans”’.4 She says she began to think that GIDS was practising in a way that ‘wasn’t actually safe’. She feared she may be contributing to a medical scandal, where an NHS service was not stopping to think what else might be going on for so many of these vulnerable children. Where the normal rules of medicine and children’s healthcare didn’t seem to apply. Where the word ‘gender’ had made herself and hard-working colleagues struggle to know what was best practice.

The mental health of one of Anna Hutchinson’s patients had deteriorated to such an extent that she felt they had to come off the puberty-blocking medication the service had put them forward for. She had brought this case to supervision to ask for advice.

Their mental health was about ‘as bad as you could get’, she explains to me. ‘There were queries of sexual abuse in the family environment. It was a mess. They were so lacking in ability to function that they couldn’t attend appointments with us.’ Hutchinson was trying to work out what they should do. She recognised the impact that removing the medication would have, ‘but equally they couldn’t stay on the blocker in a safe way’. Hutchinson felt an almost overwhelming sense of responsibility: ‘They’re on this drug because of us; it doesn’t seem to be helping with their functioning – they’re not okay; there’s so much going on that the gender is so low down now the pecking order of problems. But what can you actually do?’ It was a difficult case that she wanted guidance on.

The second case she’d brought to discuss was similarly tough. Dr Hutchinson feared there may be sexual abuse occurring within the family of this patient, too. The school had raised concerns, not just about the young person being seen at GIDS, but also about their siblings. It wasn’t clear how best to manage it. ‘These were appropriate cases for supervision. I needed help with them – to think about how best to manage them,’ Hutchinson explains. ‘And it was after speaking about those two cases that she [Davidson] said, “Why do you bring such complex cases?”’

‘What if it’s not right to put young people – ten-year-olds – on puberty blockers?’ Hutchinson had continued.

‘It is mad,’ was the reply.

Hutchinson paused. When one of the leaders of a service that helps children to access powerful, life-changing drugs comments that what they’re doing is ‘mad’, there is clearly a very big problem. It wasn’t okay just to say the work of the service was ‘mad’, Hutchinson thought. What were they going to do about it?*

Until its planned closure in spring 2023, the Gender Identity Development Service is the only NHS specialist service for children and young people ‘presenting with difficulties with their gender identity’ in England.5 It’s part of the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust in north London. GIDS also sees, or has seen in recent years, children from Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland, as well as young people from the Republic of Ireland. It is staffed by clinicians with a variety of professional backgrounds: predominantly psychologists, but also psychotherapists, family therapists, social workers and nurses. None of these are able to prescribe medication.

Not everyone seen at GIDS chooses to transition, whether socially, by changing their name and pronouns or the way they dress, or medically, by taking synthetic opposite-sex hormones, or surgically, once they’re over the age of 17. Some children might start their transition at GIDS, some may wait until they attend adult gender services, and some will choose not to transition at all.

For those who do wish to pursue a medical gender transition, though, the route begins with a referral from GIDS to a hospital that houses paediatric endocrinologists – doctors who specialise in conditions relating to hormones. There they will receive a prescription for gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (GnRHas) – most often referred to as ‘puberty blockers’. These powerful drugs are licensed by medical regulators only for use in children with precocious puberty, when children begin adolescence very young (before eight for girls, and nine for boys6). They are used ‘off-label’ – not for a condition they are licensed for – in the treatment of gender dysphoria in young people. GIDS users are most often provided with a drug called triptorelin. All puberty-blocking medications act on the pituitary gland to stop the release of the sex hormones testosterone or oestrogen. This effectively halts physical puberty, stopping the body developing secondary sex characteristics like breasts in girls, or facial hair and an Adam’s apple in boys. GnRH agonists are predominantly licensed and used to treat prostate cancer in men, but they have also been used in the chemical castration of male sex offenders.7

It’s not unusual for drugs to be used off-label, especially when administered in children. Many drugs are. But it’s usually only a matter of the dose: for example, for ethical reasons, medical trials of paracetamol would have only been carried out on adults (it’s very rare to test drugs on children), so their use in children at a half-dose would be considered ‘off-label’. What’s unusual about the use of GnRHas for use in young people with gender dysphoria is that they’re used to treat a completely different condition from the one for which they have been licensed. In the process, they function in a very different way.

Once on puberty blockers, almost all (in excess of 95 per cent) young people opt to take cross-sex hormones – synthetic testosterone for those born female, oestrogen for natal males.8 Unlike children diagnosed with precocious puberty, who later stop taking the blockers and allow their bodies to go through their natural puberty, young people with gender dysphoria don’t stop taking the blocker – they do not go through the puberty of their natal sex. Yet the long-term effects of using blockers in this way are largely unknown. Even those who have been working in the field for decades concede that research in this area is poor. Dr Polly Carmichael, the head of GIDS, admitted in 2019 how ‘we have struggled in the absence of such research to understand how the care we provide affects [patients] in the longer term and what choices they go on to make as they move into adulthood’.9 Her colleague and former head of psychology for the Tavistock Trust, Dr Bernadette Wren, agreed a year later that ‘studies are still few and limited in scope, at times contradictory or inconclusive on key questions’ and therefore GIDS clinicians are ‘concerned about overstepping what the current evidence can tell us about the safety of our interventions’.10 The position appears to have changed little in 20 years. In 2000, Dr Wren had remarked, ‘There is little evidence about the long-term effects of this intervention.’11

While there are studies that describe the self-reported high satisfaction of young people and their families of being on puberty blockers, and some improvement in mental health, others suggest there is evidence that puberty-blocker use can lead to changes in sexuality and sexual function, poor bone health, stunted height, low mood, tumour-like masses in the brain and, for those treated early enough who continue on to cross-sex hormones, almost certain infertility.12 The use of cross-sex hormones can also bring an increased risk of a range of possible longer-term health complications such as blood clots and cardiovascular disease.13

The science is not settled, and this field of healthcare is overpopulated with small, poor-quality studies. It’s often not possible to draw definitive conclusions on the benefits or harms of these treatments.14 Many studies claim to show the benefits of puberty blockers to mental health, but these have all been heavily critiqued and shown to have significant methodological flaws.15 Systematic reviews of the evidence base undertaken by national bodies have all found it wanting. England’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) found that the quality of the evidence for using puberty-blocking drugs to treat young people struggling with their gender identity is ‘very low’.16 Existing studies were small, with few participants, and ‘subject to bias and confounding’.17 A systematic review of the clinical effectiveness and safety of cross-sex hormones also found that the evidence was of ‘very low’ quality.18 ‘Any potential benefits of gender-affirming hormones must be weighed against the largely unknown long-term safety profile of these treatments in children and adolescents with gender dysphoria,’ it noted.19 National health bodies in Sweden, France and Finland have all called for far greater caution in the use of puberty blockers following reviews of the evidence.20

Some adults opt for surgery – not available in the UK until the age of 17. GIDS itself plays no active role in surgical decisions – referrals for surgery on the NHS are made by adult gender identity clinics – and young people in their care can only start cross-sex hormones if they’ve been on puberty blockers for 12 months and are approaching the age of 16.

Even for the many who go on to lead happy lives as fully transitioned adults, it can be a long and challenging journey. Some data on those who transitioned decades ago (who were mostly born male) shows that the majority continue to live as trans women, although they’re more likely to suffer from mental health problems.21 Transitioning can often require several complex surgeries and a lifetime on medication. For those who go through these stages but then later regret it, or detransition and choose to reidentify with their birth sex, the decision to transition to a different gender can prove very painful.

Dr Hutchinson needed more than vague reassurances. With such a weak evidence base underpinning the work, were GIDS simply hoping for the best? If so, they were taking significant risks, she believed, with the lives of their young patients.

There is a lot of uncertainty in this field. Uncertainty over the evidence base, over the outcomes, and about whether or not medical transition will be the best option for any particular individual in the long term. Uncertainty, or lack of agreement at least, on what being trans even means. Is it something that is transitory or fixed from birth? The question was how best to respond to that uncertainty. For Hutchinson, with such serious consequences at stake, it wasn’t okay to concede that so much was uncertain, and then not to manage the associated risks adequately. She accepted the argument for referring young people for puberty-blocking medication even without a strong evidence base, given the intensity of distress felt by some young people. There were consequences to not acting, just as there were for acting. But the reality for many of the young people attending GIDS, who often presented with multiple other difficulties that required urgent attention, made the decision even more complicated.

Were these young people ‘well and functioning’, in every other sense, Hutchinson explains, there could well be an argument in favour of medical treatment to address their gender dysphoria. These patients were ‘very sure’ and ‘very committed’ to transition. ‘I’m not ever putting their identity in doubt here. I very much believe that that’s what they felt they wanted at that time, and I can see why,’ she says. ‘But we had to see the whole picture. And when there was, possibly, sexual abuse going on at the same time, plus other complex things, I just couldn’t be so casual about the risk that we were not fully understanding what was going on for these kids.’

It didn’t help that Hutchinson’s list of unanswered questions was getting longer and longer. Why were more teenage girls being referred to the clinic than ever before, many of them with no previous problem with their gender identity in childhood – girls who often had complex mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, eating disorders and self-harm?22 Could the past traumas of some of these children explain why they wanted to identify as a different gender to escape from their bodies?23 Did the increasing number of patients who appeared to experience homophobic bullying before identifying as transgender need to be explored in greater detail?24 Was GIDS actually medicating some gay children, and some on the autistic spectrum?25 And by what method could staff tell the difference between the patients who would benefit from treatment and those who would not? These were all profound questions, with deep ethical implications.

‘We know that not all young people who identify as trans go on to live as trans adults,’ Hutchinson says. ‘We’ve always known that.’ In every study in this field, poor as the evidence base is, there have always been some young people who identified as a different gender, felt intense distress surrounding this and wanted to transition, but for whom those feelings resolved. They went on to live as adults without feeling the need to change their bodies by use of hormones or surgery, and became content with the bodies and sex they were born with. These studies are small and imperfect, with methodological flaws, but, according to the NHS, showed that in ‘prepubertal children (mainly boys)… the dysphoria persisted into adulthood for only 6–23%’ of cases.26 Boys in these studies were more likely to identify as gay in adulthood than as transgender. According to the fifth edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – known as the DSM-5 – rates of childhood gender dysphoria continuing into adolescence or adulthood ranged from 2 to 30 per cent for males, and 12 to 50 per cent in females.27

What Hutchinson wanted from the leadership of the service was an acknowledgement of the risks of the work: prescribing powerful drugs with largely unknown consequences to children. ‘Because by not acknowledging the risks, we were kind of colluding with the idea it would work for everybody. And at that point, I think it was so clear, it wasn’t going to work for everybody.’ GIDS, she says, was responsible for every single young person coming through its doors. ‘The ones who identify as trans for life are our patients, and we want to help them; the ones who aren’t going to identify for life are equally our patients, and equally our responsibility.’

Hutchinson continues: ‘It wasn’t like I was saying, you mustn’t give anyone the treatment. But what I was saying is we need to acknowledge it isn’t going to work for everybody; that we could be getting this wrong; that people could be harmed by this treatment. And it’s only through the acknowledgement of those risks, you could do anything to minimise those risks. At that point, by not acknowledging the risks, we weren’t managing the risks at all.’

This is not a story which denies trans identities; nor that argues trans people deserve to lead anything other than happy lives, free of harassment, with access to good healthcare. This is a story about the underlying safety of an NHS service, the adequacy of the care it provides and its use of poorly evidenced treatments on some of the most vulnerable young people in society. And how so many people sat back, watched, and did nothing.

* These words and phrases are recorded verbatim in Anna Hutchinson’s contemporaneous written notes. Dr Hutchinson later relayed these conversations, and wider concerns, to the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust’s medical director, during an interview in December 2018 which formed part of an official review into GIDS. A transcript of this interview was admitted into evidence during an employment tribunal against the Tavistock Trust. Dr Hutchinson also included these conversations as part of an official witness statement for the tribunal and affirmed its contents under oath. In a written response provided to the author in 2022, Dr Sarah Davidson said that she supported Dr Hutchinson ‘in her day to day work and on more difficult or complex cases’ and was ‘always available to give her the support and guidance needed’ as her supervisor. Dr Davidson said she did not recall making the comment about ‘complex cases’ and found it to be ‘highly unlikely’, given her role. She added that she did not recall a specific discussion referencing ten-year-olds and puberty blockers, but that the language recorded by Dr Hutchinson was ‘not in keeping with the language I would use for any patient’. Dr Davidson did recall ‘a number of discussions with Dr Hutchinson about the concept of harm and what it meant in this unique and challenging area of practice’.

2

The Vision

The Gender Identity Development Service was the creation of child and adolescent psychiatrist Domenico Di Ceglie. Described by his long-term colleague Dr Polly Carmichael as ‘Italian, obviously, and a bit of a terrier, and also a very curious man’, he wanted to, in his own words, create a service ‘for children with these rare and unusual experiences’ of having a gender identity that didn’t seem to match the biological body they were born with.1

Di Ceglie was spurred on by a solitary case he’d worked with in the early 1980s, a teenager ‘who was claiming that she was a boy but in a female body’. Although she spoke very little during their psychotherapy sessions, Di Ceglie felt ‘there was something very profound about her sense of identity of being a boy which could not be easily explained and that was fundamental to her being.’2

Working as a consultant child psychiatrist in Croydon, south London, shortly afterwards, he and a couple of colleagues attempted to see all the patients who presented with gender identity problems in the area. In a borough whose population stood at around 300,000, they ‘ended up with 3 or 4 cases’.3 Despite the small numbers involved, the complexity of the cases he saw convinced Di Ceglie of the need for a specialist service.

The term ‘gender identity’ was coined by American psychiatrist Robert Stoller in 1964, and is generally understood to mean someone’s personal sense of their own gender.4 (For some that may not be the same as their physical sex – a trans woman, for example, is born with the physical body of a man but has a gender identity of a woman. But the concept is not without its problems; many people feel they don’t have a gender identity at all.) Di Ceglie read Stoller’s work, along with ‘other literature on trans-sexualism’, when he encountered his first case.5 The two met in person at a 1987 conference, with Stoller apparently being ‘very encouraging’ of Di Ceglie’s plans to start a service for children and adolescents. ‘He thought that there was a real need for such a service and predicted that there would be many referrals and a lot of interesting work.’6

In September 1989, Di Ceglie succeeded in setting up the Gender Identity Development Clinic for children and adolescents within the Department of Child Psychiatry at St George’s Hospital in south London. The name was relevant: the emphasis would be in promoting the development of the young person’s gender identity, not changing it. Staff were to maintain an open mind as to what solution the young person might settle on in terms of managing their gender identity and to support families in reaching that solution – whether it be to transition medically, or to become reconciled with their own sex without changing their body. But Di Ceglie could see that, in some cases, by addressing other difficulties experienced by the child – things like depression, abuse or trauma – it might ‘secondarily affect the gender identity development’.7 In other words, sometimes the gender identity difficulties might resolve if other difficulties being faced were dealt with as well.

Not attempting to alter the young person’s gender identity, but instead fostering ‘recognition and non-judgemental acceptance of the gender identity problem’ would become one of the core guiding principles of the service.8 Others included trying to ‘ameliorate associated emotional, behavioural, and relationship difficulties’, encouraging ‘exploration of mind–body relationship’ by working with professionals with other specialities, and helping the young person and their family ‘tolerate uncertainty’ with their gender identity development.9 Although they were written in the 1990s, those leading the service in later years say that these principles endured throughout: ‘Those therapeutic aims still represent the core values of the service – they’re Domenico’s lasting legacy,’ said Bernadette Wren, a member of the GIDS Executive team from 2011 to 2020. ‘He grasped that if you want to have a genuine engagement with young people you have to take very seriously what they feel and what they say.’10

Di Ceglie’s peers were baffled. ‘Originally people were saying to me, you know, what do you want to do? Who are these children?’ Di Ceglie recalled, speaking in 2017. ‘And then somebody said to me, “But is it that you, [by] creating a service, you are creating the problem?”’ Di Ceglie reflected. ‘I don’t know the answer to that question, but still!’ he laughed.11 This question would grow ever more pertinent decades later.

The service in these early days was largely therapeutic: providing individual therapy, family work and group sessions. Some young people would remain in the service for years, others could be helped relatively quickly. In terms of outcomes, Di Ceglie said that only about 5 per cent of the young people seen at his clinic would ‘commit themselves to a change of gender’ and that ‘60% to 70% of all the children he sees will become homosexual’.12 At this point in time, the small number of studies that existed supported this general picture.13 These early findings would later appear to be forgotten as demand for GIDS grew and the clinic became busier. Alongside its therapeutic work, the clinical team also visited schools to help them understand how best to help young people struggling with their gender identity, and tried to educate other health professionals. There had been little need to ‘radically change’ this model over the clinic’s early years, but it had been refined ‘particularly with reference to physical interventions’ so that some adolescents could access medication that would block their puberty.14

If, after extensive therapy and thorough assessment, a young person’s distress in relation to their gender remained throughout puberty, they met a series of strict criteria and were around 16 years old, they could be offered medication to halt the process of their natural sex hormones being released – puberty blockers. In the 1990s little was known about how these drugs might help in the treatment for gender-related distress, and the service was cautious about recommending them. The blockers were not prescribed or administered by Di Ceglie and his colleagues themselves, but rather by paediatric endocrinologists, working alongside the gender identity team.

As the 1990s progressed, however, the Royal College of Psychiatrists established a working party to establish best practice on when, whether and how to treat young people with gender-related distress with medication. It followed a conference Di Ceglie had hosted in 1996, bringing together colleagues from around the world. There were very few professionals working with this group of children and adolescents, and it was an important moment to share ideas and experiences. A team in the Netherlands were already reporting early data that beginning the process of transitioning to another gender in late adolescence could lead to favourable outcomes in adulthood.15 Should the UK follow suit?

A pioneer in this field, Di Ceglie co-authored the Royal College’s resulting official guidelines, published in January 1998.16 The guidelines explained that gender identity ‘disorders’ were ‘rare and complex’ in children and adolescents, more common in boys, and often associated with other difficulties. The document stressed that, when compared with adults, there was ‘greater fluidity and variability in the outcome’, and only a ‘small proportion’ of young people would go on to transition in adulthood. The majority, it said, would be gay. The first stage of any treatment, therefore, should be extensive therapy and include taking a full family history. It should focus on improving ‘comorbid problems and difficulties’ in the young person’s life and reducing their distress caused by both these and their gender identity. The guidance advised that, if used at all, physical interventions should be staged: first puberty blockers, which are described as ‘wholly reversible’; then ‘partially reversible’ cross-sex hormones (oestrogen and testosterone) to either feminise or masculinise the body; and, finally, ‘irreversible’ surgical procedures. This staged approach remains the same today.

While surgery was strictly ruled out before the age of 18, the document didn’t make any age stipulations when it came to the use of puberty blockers. However, it recommended that adolescents have experience of themselves ‘in the post-pubertal state of their biological sex’ before starting any medications. This was considered vital to being able to provide ‘properly’ informed consent. The authors urged a ‘cautious’ approach and argued that physical interventions ‘be delayed as long as it is clinically appropriate’. They also stressed the need to ‘take into account adverse affects on physical growth’ that might result from blocking hormones.

The guidance explained that adolescents could present with ‘firmly held and strongly expressed’ views on their gender identity, and that the pressure to prescribe or refer young people for these drugs could be great. However, this distress and certainty had to be understood in the context of adolescent development – a time of great fluidity. Strength of feeling ‘may give a false impression of irreversibility’, it explained. ‘A large element of management [of the gender-related distress],’ the guidance said, ‘is promoting the young person’s tolerance of uncertainty and resisting pressures for quick solutions.’

Professor Russell Viner (who would later become president of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, 2018–21) started providing endocrinology services to GIDS patients in 2000. At that time, using puberty blockers at all was seen as ‘an advanced approach’, he tells me. Other countries, such as the United States, were giving older adolescents large quantities of cross-sex hormones instead. ‘The safest thing to do is to turn the hormones off,’ he explains. ‘But if that person wanted to transition from male to female, another option would be to give them large doses of oestrogen. But you’d have to give them really very large doses of oestrogen to suppress the body’s own production of male hormones.’

There were two main reasons for making 16 the age at which blockers could be used, Professor Viner explains. First, from 16 adolescents largely have ‘adult rights’ to consent to treatment or refuse it. And secondly, ‘from an endocrine point of view’ it fitted because most people had almost completed puberty by this point. The rationale for using the blocker post 16 was ‘to make it safe to introduce small doses of opposite-sex hormones if that young person wished’, although GIDS and its associated endocrinologists did not do this at the time, and there was a notion, Viner says, ‘that this gave them a space to think, away from the drive of their own hormones’.

The endocrinology side was linked, but kept separate to GIDS, Viner explains. ‘And I think that was done for a particular reason, to emphasise the importance of the brain and the mind rather than the body.’ In the United States and elsewhere, gender services could be run by endocrinologists, with the overwhelming focus being on ‘fixing’ the body. But he (and Dr Di Ceglie) strongly believed in the need for ‘a mental-health-led service’, where ‘the key message’ was that while there were things you could do with the body, ‘mental-health treatment is the most important thing.’

In 1994, five years after the gender identity clinic had first opened its doors, it moved 11 miles north, across London, to the Portman Clinic – an old picturesque Victorian house that, together with the Tavistock Centre – a far less attractive 1960s concrete building – formed the Tavistock and Portman Trust.† It has remained part of the Trust ever since. Although referrals doubled in the space of two years, from 12 in 1994 to 24 in 1996, the service remained small, as did the knowledge base relating to this group of young people and the best way to help them.17

Di Ceglie’s 1996 conference was written up as a book, with the help of freelance social-science researcher David Freedman.18 Clinicians from around the world discussed their work and patients. Eating disorders, child sexual abuse, trauma and bereavement were all mentioned as events that had preceded the development of gender-related distress in the case vignettes that featured, but proper data and analysis were hard to come by.

‘The Trust said, “We don’t really know a lot about what’s happened to these young people, or their characteristics or anything – is it possible to do a sort of retrospective audit?”’ Freedman recalls. The request came around the year 2000, and he happily accepted the challenge. Along with Di Ceglie and two others, they designed a study that would try to shed light on this patient population.

They went through all the case notes of the young people whom Di Ceglie and colleagues had seen since the unit had opened in 1989. And although many of the staff working back then were doing so part-time, Freedman was left with the impression that the work of the service was slow and very careful. ‘My feeling was that, in those days, the service really did try to offer a non-judgmental, safe space where the child and the family could work through things,’ he says. The young people, Freedman reflects, were clearly distressed, with families feeling confused and isolated. Gender identity issues were not generally discussed in society, nor known about by other professionals in healthcare, schools or elsewhere, he tells me.

Trawling through individual cases files was ‘messy’, but that’s what they did, creating a list of measurable features that could be examined in order to produce meaningful conclusions.

‘One of the things that came out of this was you couldn’t predict at the beginning what the outcome would be,’ he explains. Some children persisted throughout – remaining clear that they wanted to transition to the opposite gender. Others ‘would come in with really a strong desire that they wanted to change gender’, but later decide they no longer wanted surgery, or found ‘through exploration’ that they could manage the distress ‘without changing their gender identity’. This didn’t mean life was ‘absolutely perfect’ for this latter, larger group by any means, but only the minority would ‘go on to transition fully or adopt an identity in the other gender’.

By the time of the audit, around 150 children and adolescents had been seen by the specialist service.19 The very recent ones were excluded from the analysis, but the team were left with 124 patients’ records to explore in order to try to establish a profile of the ‘characteristics of the children and adolescents referred to the service, the source of referral and the associated clinical features’.20 Two-thirds were boys, and on average patients had been first referred aged 11. The most common problems experienced by the children were associated with relationships, the family context and mood, the researchers noted. Fifty-seven per cent experienced difficulties with their parents or carers, 52 per cent had relationship difficulties with peers, while 42 per cent suffered from ‘depression/misery’.21

Close to four in ten young people (38 per cent) had families which had mental health problems; the same proportion experienced family physical health problems. A third claimed to have been the victim of harassment or persecution.

A closer look at the young people’s family circumstances and behaviours provides some startling findings. Over 25 per cent of those referred to the clinic had spent time in care. That compares to a rate of 0.67 per cent for the general children’s population (2021).‡ The analysis also notes that while 84 per cent had been living with their ‘family of origin’ at the time of referrals, this had fallen to 36 per cent at discharge.22 GIDS sees young people up to the age of 18. Of those children and adolescents seen by the service at this point, 42 per cent had experienced the loss of one or both parents through bereavement or separation (predominantly the latter). Close to a quarter of those aged over 12 had histories of self-harming, and the same proportion exhibited ‘inappropriately sexualised behaviour’.

The audit of cases showed that it was very rare for young people referred to GIDS to have no associated problems. This was true of only 2.5 per cent of the sample.23 On the other hand, about 70 per cent of the sample had more than five ‘associated features’ – a long list that includes those already mentioned as well as physical abuse, anxiety, school attendance issues and many more. Those who were older (over 12) tended to have more of these problems.

The paper itself is unable to explain what might be going on. Instead, it poses several alternative hypotheses. It may be that families experiencing other troubles ‘find it more difficult to handle their children’s problems and thus bring their children to health care agencies more often’. Alternatively, there might be a link between family difficulties, some of which might be traumatic for the child, and the development of gender identity difficulties.24 Because either could be case, the authors stress the importance of establishing ‘full histories’ with young people and their families.

It’s impossible to say for sure whether young people with mental health problems and traumatic pasts are more likely to adopt a trans identity, or the other way round – that the stigma and prejudice faced by trans people somehow makes the young person more vulnerable to other problems. As is common in the field, the research does not provide concrete answers. These early data were meant to be used to establish the needs of this patient group, improve service delivery and plan future research.25 Indeed, David Freedman describes this work as the Gender Identity Development Service’s ‘first clinical audit’.26

It was also its last.§

While it provided a unique and safe space for children and their families to talk through their gender-related distress, the Gender Identity Development Unit – as it was also known – was not an integral part of the Portman Clinic.¶ It was based in a ‘broom cupboard’, according to some. ‘It was such a small unit; it almost didn’t figure in people’s mind,’ says Stanley Ruszczynski, who joined the Portman in 1997 and would go on to become the clinic director.

Despite its small size, it wasn’t long before Di Ceglie’s colleagues in the Portman felt unease at this new service. The model it used, they believed, was at odds with the core principles underpinning this world-leading provider of mental health care. The Tavistock and Portman is internationally renowned for its commitment to talking therapies, or psychotherapy. One former senior clinician described the ‘parents’ of the Trust as being systemic psychotherapy – which looks at the groups an individual operates in and how these shape behaviour – and psychoanalytic (or psychodynamic) psychotherapy, which builds on Freud’s ideas about the subconscious and the influence this can have on our behaviour.27

In the late 1990s and early 2000s the Portman itself received referrals from adult transgender patients and ran groups for those who were both pre- and post-operative. Ruszczynski, who trained as a social worker but became a consultant adult psychotherapist, had worked with about half a dozen adult patients and been troubled by the cases. In particular, a couple who had attended where the husband had surgically transitioned to a woman.

‘What I remember about that story was that he wanted to detransition… to go back to being a man.’ The man had explained how he had woken up from gender reassignment surgery having had his genitals removed, and immediately ‘knew he’d made a mistake’.