Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

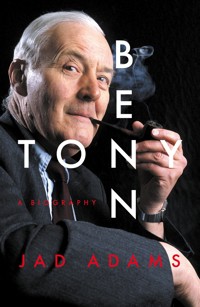

Jad Adams has worked as a television producer and a Fleet Street newspaper journalist. He knew Tony Benn well for the last twenty-five years of his life. He was the last researcher to have full access to the extensive Benn Archive in Benn's basement office, prior to its being given to the British Library. Jad's political books include Women and the Vote: A World History, Gandhi: Naked Ambition and The Dynasty: The Nehru–Gandhi Story. His television work has included biographies of Bill and Hillary Clinton, the Nehru dynasty and Lord Kitchener. He has also specialised in work on the 'decadent' era of the nineteenth century, including Decadent Women: Yellow Book Lives; Madder Music, Stronger Wine: The Life of Ernest Dowson; and Hideous Absinthe: A History of the Devil in a Bottle. Jad has written two novels: Cafe Europa and Choice of Darkness. He lives in London and on the Greek island of Leros. His website is www.jadadams.co.uk

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 1159

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i“Jad Adams has written a well-researched and sympathetic biography – though not a hagiography – about someone who will live for ever in the pantheon of Labour heroes. Here is a man capable of arousing great and contradictory passions among friends and foes alike, by turns inspiring, infuriating, courageous, irresponsible, right about some of the big issues of the day and sometimes just plain wrong.”

Chris Mullin, New Statesman

“This is a serious biography which all living politicians (and a good many dead ones too) could be proud to have written about them … Mr Adams takes us through Tony Benn’s long career with considerable narrative skill and a more than adequate knowledge of both the minutiae and the broad sweep of left-wing politics.”

Roy Jenkins, Sunday Telegraph

“I am in a position to make an informed judgement on Jad Adams’s biography. I find it an extremely accurate account of all those events and situations of which I have first-hand knowledge. Adams is perceptive in the details with which his pages are laced. And, unlike many who have done a lot of work in television, he writes in a style that makes a reader wish to read on.”

Tam Dalyell, The Scotsman

“There is real added value in Mr Adams’s pages … Adams has won a permanent place in the Benn literature and that matters.”

Peter Hennessy, Times Educational Supplement

“An exceptionally good example of what is normally an awkward genre, the biography of a living public figure … Told with considerable grace and style … candour and warmth of narrative.”

Anthony Howard, Sunday Times

“Benn’s turbulent career makes fascinating reading in Jad Adams’s biography.”

Daily Express

ii“Benn’s character shines through this fat but very readable biography … Benn has been subject to fierce and frequently unfair personal attack. This book sets out the case for him, and it is one worth making.”

Allan Massie, Daily Telegraph

“Extremely well researched and documented … For those who are interested in a study of political perversity, this book is worth reading.”

Nicholas Ridley, The Guardian

“Jad Adams has written an able account of this strange career now becalmed. He writes as a strong sympathiser who nevertheless can criticise.”

Douglas Hurd, Sunday Express

“Jad Adams has an enviable wealth of source material. The result is an enjoyable read.”

John Biffen, New Statesman

“This book is long, detailed, well written and well researched.”

Simon Hoggart, The Observer

“This is some career and this is some book, well documented and packed with atmosphere and insight. A strong argument holds this considerable volume together. It might be described as the biographical dialogue between Benn’s considerable political achievements and the fact that he failed to become leader of his party and to carry his Cabinet colleagues with him to realise political goals that were tremendously important to him. But whether we think of him as a failure or as a success, his importance in British politics since 1945 cannot be denied.”

Robert Giddings, Tribune

“From start to finish this is an enjoyable and readable book.”

Karl Statton, Labour Briefing

iii

v

For Julie

vi

Contents

List of Illustrations

Antony, David and Michael Benn, 1930.

The family at Stansgate, 1932.

Oxford debating team, 1947.

The Benn family at play.

H-Bomb National Committee, 1954.

On the set of TheABCofDemocracy, 1962.

Priests of the new technology, 1966.

Shadow industry minister at Upper Clyde Shipbuilders, 1971.

Tony Benn election poster.

Last appearance as an MP at the House of Commons.

With the Stop the War campaign.

A Tony Benn’s-eye view of Trafalgar Square.

The author and publishers would like to thank the Tony Benn Archives for permission to use the above photographs.

Introduction: TONY BENN’S CONTEMPORARY RELEVANCE

Readers of the DailyExpressare not used to seeing Tony Benn’s speeches being reported with enthusiastic praise, but one day in 2019, they opened their papers to see a report of a ‘brilliantly explained … epic Tony Benn speech’.1 In it, he addressed a familiar Benn theme: the sacredness of the vote, which he considered the main safeguard for people who did not have power or money.

Launching a scathing attack on the United Kingdom’s membership of the European Community ahead of the 1975 referendum debate, Benn said, ‘Common Market membership devalues and downgrades the vote because it prevents people using the ballot box to adopt policies, change policies [and] change men who adopt policies.’2 The reference to the Common Market and politicians as ‘men’ rather dates the comment, but it is clear from the Express’s printing of the speech on 31 October 2019, in response to arguments about the implementation of the result of the 2016 Brexit referendum, that a major organ of the ascendant Tory Party still felt these ideas deserved prominence in the post-Brexit world.

Earlier, on 24 May 2016, in the run-up to the referendum, the conservative magazine TheSpectatorprinted in full an article by Benn, which it still considered burningly relevant. Benn said:

The European Community has now set itself the objectives of developing a common foreign policy, a form of common nationality expressed through a common passport, a directly elected assembly and an economic and monetary union which, taken together, would in effect make the United Kingdom into one province of a Western European state.3

It was, therefore, not only friends of Benn but those who at other times had been savage opponents who felt they should be filling their columns xwith words spoken by a man now dead who had last enjoyed political power forty years previously. Tony Benn continued to contribute to political discourse.

The arguments about democracy and sovereignty, and the very fact that the Brexit referendum happened at all, gave Benn’s ideas an impetus in the twenty-first century. Up to the early 1970s, Britain was an established, representative democracy where voters chose a local, constituency representative to exercise their judgement on national issues in Parliament. This was altered by Benn, who was the father of the British referendum, an idea he promoted when no other politician of stature was doing so.

In a groundbreaking speech in 1968 at Llandudno, Benn channelled popular dissatisfaction with what he described as ‘a system which confines [people’s] national political role to the marking of a ballot paper with a single cross once every five years’.4 He called for a range of means to improve popular representation. There were six areas where he thought public representation should be improved: legislation for the freedom of information; the improvement of data collection by government; the opening up of the mass media to minority views; the encouragement of representative organisations, such as pressure groups and trade unions; the devolution of power to regions and localities; and the holding of referendums on national issues. He thought referendums could start with those issues which were currently the subject of Private Members’ Bills, which were often ‘matters of conscience’.5

No one seized and ran with the referendum idea and there was no popular enthusiasm for it, but Benn did not relent, continuing to argue for what he called ‘popular democracy’. Two years after the Llandudno speech, when Labour was in opposition, the government of Edward Heath was planning British entry into the Common Market. Benn proposed a referendum on the issue, arguing that Britain should not go in without a referendum or general election. There was no enthusiasm from colleagues or the public, but as time passed, it increasingly seemed like not only a good idea but the only idea Labour had which would both settle the argument and provide a mechanism for the different factions in the Labour Party to go forward on a united policy.

By 1972, Benn’s referendum idea came into its own as one of Labour’s manifesto proposals for the next election, which took place in February 1974, where Labour garnered votes from anti-marketeers who thought the referendum their only chance to exit the bloc. Benn had gone from xinot being able to find a seconder for his referendum motion and having it rejected at the party conference to being one of the architects of Labour’s victory in 1974.

The constitution having been widened to encompass referendums meant they now became common: they took place on Scottish and Welsh devolution; on the extent of power the Scottish and Welsh assemblies should have; on regional assemblies in the north-east and in London; and (locally) on whether a region should be represented by a directly elected mayor. The most important of the referendums in the constituent nations was that on the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, promising the end to thirty years of violent unrest. Another took place on replacing the first-past-the-post voting system in 2011. There is little dispute now on the need for referendums on major constitutional issues.

In 2013, Prime Minister David Cameron promised to hold a referendum on continued membership of the European Union, as a solution to the problem of right-wing defections from the Conservative Party from its ‘Eurosceptic’ wing. It was also a recognition that, as the United Kingdom’s membership of the European Union had been confirmed by a referendum, it could only be reversed by one. Cameron acknowledged the importance of Benn when he was asked about the books which had most influenced him and he named Benn’s ArgumentsforDemocracy, calling it ‘a very powerful book’.6 For good or ill, the Britain of today – post-Brexit Britain – owes much to Tony Benn.

Benn’s first constitutional reform had been over the renunciation of peerages. He had inherited a peerage on the death of his father, Lord Stansgate, which disqualified him from being an MP. His subsequent long campaign culminated in the Peerage Act of 1963, which was a serious blow against the hereditary principle in the House of Lords (which, of course, was why his opponents fought against him so fiercely). By the present day, as the constitutional historian Vernon Bogdanor says, ‘No one today suggests that a hereditary peer should not be allowed to renounce his peerage.’7

By the third decade of the twenty-first century, the House of Lords had accepted some dubious characters as noble peers and peeresses, some after very little public service indeed, and was the largest legislative body in the world at more than 800 members, vastly more even than populous countries like India, and all drawing on the public purse.8 That a discredited Upper House was ripe for reform was not in doubt, but the form such reform should take was still open to discussion. Benn had xiicriticised the patronage of the Prime Minister in appointing legislators: ‘It is not just that an inherited seat in Parliament is an anachronism – though it is. It is that the powers of patronage which are used by Prime Ministers to place people in Parliament by personal preference are equally offensive.’9 His proposal from his 1991 Commonwealth of Britain Bill, of a fully elected Upper House, half male and half female by regional representation, was still an option. That may well resurface as debate about the future of the House of Lords continues. A proposal to remove the remaining ninety-two hereditary peers was in the King’s Speech in July 2024.

Another field of Benn’s constitutional reforms was in the democratisation of the Labour Party generally, though the enduring success (in Labour and other parties) was over the election of the leader and therefore of the Prime Minister. On 6 June 1968, Benn wrote an open letter to his Bristol South-East Labour Party, presenting his theme: ‘The keynote of party reconstruction must start with a search for a greater participation in decision-making.’10 Benn argued for a wider franchise of the party leader than just Members of Parliament. The Campaign for Labour Party Democracy was formed in 1973, to take this and other ideas of accountability forward.

The political battles over democracy in the party took place during a bitter period of Labour in-fighting following Margaret Thatcher’s victory in 1979, with arguments over what form an electoral college for the leadership should take – in particular, what proportion should be for the trade unions. The electoral college that was finally chosen did Benn no good personally; under the first election using the system, in 1981, he lost the deputy leadership to Denis Healey. However, a constitutional change had been made and a further reform by John Smith in 1993 went back not to the old system but to One Member One Vote from a list initially selected by MPs.

The Conservative Party had lagged behind with the reform of the election of the party leader, but in the wake of its catastrophic defeat in 1997, the new leader, William Hague, pushed through reforms. Now Tory MPs would choose two candidates who would go through to a ballot of party members. By the beginning of this century, then, the two parties which had any chance of selecting a Prime Minister had adopted a Bennite reform; the democratisation of the Labour Party became the democratisation of the Conservative Party.

It is proof of the validity of Benn’s arguments that they are not now xiiicontested and are adopted even by those who previously opposed them. Benn has been responsible for more constitutional change in Britain than any other politician, excepting some of those who became Prime Minister, and his ideas continue to resonate.

One could very reasonably say that Benn’s ideas were tested in the 2017 and 2019 elections under Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership and led to a catastrophic defeat. Certainly, there was a defeat in 2019 which continued the downward trend in the Labour proportion of seats in the House of Commons, which had been in evidence since the 2001 election (with the one exception of 2017, when thirty seats were gained and Theresa May lost her overall majority). We select a government by the number of constituencies won and we cannot pretend otherwise, but it is illuminating to look at the raw figures of people voting – we could say people convinced by an argument – which give a picture other than catastrophe. The election of 2017 saw 12.8 million people vote Labour, more than at any other time this century. Even the election of 2019 saw Labour take more votes (10.2 million) than the party did in the Keir Starmer election of 2024 (9.7 million). Corbyn’s party, with its Bennite approach, was literally more popular, meaning more people voted for it. In the 2024 election, the votes were more favourably distributed, hence the large majority of seats. The Labour victory in 2024 was the result of the collapse of the Tory and Scottish National Party votes as well as exemplary Labour Party management, which targeted winnable seats and took a centrist approach that even the press found it hard to fault. However, there was no overwhelming endorsement of Labour’s policies.

Once Labour was in power, though, there was more than a little Tony Benn in the King’s Speech. Starmer’s government was hardly Bennite, but the extent to which ideas that Benn would wholeheartedly approve of were part of Labour’s programme demonstrated his far-sightedness and influence. Benn had been the most prominent proponent of socialism at a time, in the 1980s and ’90s, when the tide was against him and for marketplace capitalism. He kept the idea of public ownership in speeches and such publications as his ArgumentsforSocialism. He looked as if he were crying in the wilderness, as every public utility was sold into private hands.

By the time of the 2024 election, however, the nation appeared to be emerging from a collective dream. No one, it seemed, could remember why it had seemed a good idea for natural monopolies like water, gas, electricity and rail to be put into private hands.xiv

In no area – service to the public, pricing or investment in infrastructure – were the private companies running utilities doing even a reasonably competent job. The idea that marketplace economics could provide public services in these areas had been tested to destruction. Failed water companies were on the verge of bankruptcy and pumping sewage into waterways – every single one of them had failed in this regard by July 2024.11 Despite high profits for energy companies, families were making a choice to eat or heat their homes, power prices were so high yet energy companies were still failing.12 Passenger rail companies were already being taken back into public ownership even before the election.13 The new Labour government announced in the King’s Speech in 2024 that all rail companies would be taken into public ownership and, in a reversal of another failed privatisation policy, the Better Buses Bill would remove the ban on publicly owned buses, so local councils could take control of their local bus services.14

Though public utilities had utterly failed in private hands, the picture is hardly universally Bennite. No one was talking of reintroducing the provisions of Benn’s Industry Act; workers’ co-operatives were on no one’s list of solutions for Britain’s problems; the new publicly owned Great British Energy company was not an updated version of Benn’s British National Oil Corporation (though there were enough similarities to make comparison possible).15

Twenty-five years after Tony Benn left Parliament, and 100 years since his birth, his name is still evoked as a champion of socialist values. He is still quoted in debates on such vital issues as war and national economic direction. His unwavering commitment to democratic principles and the betterment of society left an indelible mark – that is his legacy today.

1

Childhood and Family

‘When I was born in 1925,’ Tony Benn reflected while in his sixties, ‘twenty per cent of the world was ruled from London. In my lifetime I have seen Britain become an outpost of America administered from Brussels.’

The young Benn was able to observe Britain’s changing role in world affairs from the vantage point of an intensely political home. His first coherent political memory is of visiting Oswald Mosley, then a Labour MP, at his home in Smith Square. He remembers thanking Mosley for his hospitality in what he has described as his first speech. When he was five in 1930 he went to see the Trooping of the Colour from the back of 10 Downing Street. He was more impressed with the chocolate biscuits than with meeting Ramsay MacDonald, the Prime Minister. A deeper impression was made by the gentle yet strangely dressed figure of Gandhi, in London in 1931 for the second Round Table Conference, which Benn’s father had convened when Secretary of State for India.

What made a lasting impression on Benn was the knowledge that the powerful talked, walked and ate like everyone else, lived in houses just like him, were accessible. Schoolmates later talked of his self-assurance, of his confidence in his own position. He could respect the mighty as people but he had learned as automatically as he learned to speak that they were just other folk doing a job. When he was later to challenge prime ministers and sit with the Queen discussing stamps he was not tongue-tied. Inoculated by minute exposure from an early age, he had developed an immunity to awe.

Tony Benn was the second son of William Wedgwood Benn and Margaret Benn, later Viscount and Lady Stansgate. He was named Anthony because Sir Ernest Benn, his uncle, had bought a painting depicting a Sir Anthony Benn who had been a courtier in Elizabethan 2times. The portrait shows a dark, sombre-looking man with no obvious connection with the latterday Benn family. Mrs Benn saw the painting for the first time in Sir Ernest’s dining room when she was carrying the baby and decided, if it was a boy, to call him Anthony. ‘We nearly didn’t,’ she said, ‘because I said it will be sure to be shortened to Tony and I dislike the name Tony very much.’1 Ernest Benn left the portrait to his nephew in his will but sold it when Tony Benn joined the Labour Party on his seventeenth birthday. The picture re-entered the family when the new owner sold it to Tony Benn’s wife Caroline.

Baby Anthony received as his second name Neil, because his mother wanted to remind him of his Scottish ancestry. The name Wedgwood is a direct reference to his father. William Wedgwood Benn had been so christened in 1877 because his maternal grandmother, Eliza Sparrow, was a distant cousin of the pottery family. Tony Benn’s debt to his father is clear from a tribute he wrote in 1977, ‘His inherited distrust of established authority and the conventional wisdom of the powerful, his passion for freedom of conscience and his belief in liberty, explain all the causes he took up during his life, beginning with his strong opposition to the Boer War as a student, at University College, London, for which he was, on one occasion, thrown out of a ground-floor window by “patriotic” contemporaries.’2

Wedgwood Benn was the youngest person in the new Parliament in 1906 when at the age of twenty-eight he was elected for St George’s in the East and Wapping, with a ‘No Tax on Food’ slogan. This was the first election which his future wife Margaret Holmes could remember. She was then only eight years old but had been born into a Scottish Liberal family, so the party’s landslide was a significant feature of her childhood. The 1906 election produced the first great radical government of the century, which, with its Liberal successors, went on to introduce old-age pensions, national health and unemployment insurance and curbed the power of the House of Lords.

Before the election Wedgwood Benn had been working in the publishing business which his father had built up and had been supporting various trade union causes in the East End of London. He was already a radical, arguing for Home Rule for Ireland, for a Jewish homeland and for the protection of trade union funds, which had become liable to seizure as a result of the Taff Vale judgement by the House of Lords in 1901.

He became a junior Whip and junior Lord of the Treasury in 1910. One trait of his which was also to be apparent in his son’s make-up was a 3love of gadgetry. He arranged for the installation in the Whips’ room of telephones, a counting machine and a pneumatic tube to carry messages to and from the front bench. In the Whips’ room he was in an ideal position to see how Parliament functioned. He was fascinated by the way the constitution and parliamentary procedure and democracy all fitted together to form part of the machinery of government, an insight which once led him to call Parliament a ‘workshop’. It was this understanding, founded on sympathy, which prompted Lord Halifax to describe him as ‘[one of] the best Parliamentarians of my time in the House’.3

In 1914 he felt compelled to serve in the war, even though his age (he was thirty-seven) and his occupation as an MP exempted him. He joined the Middlesex Yeomanry, a mounted regiment for which he was eligible only because a fellow Liberal MP gave him a polo pony and groom. He served in the Dardanelles, then his individualistic talents found alternative means of expression. Joining the Royal Naval Air Service, he participated in the bombing of the Baghdad Railway. He was rescued from a sinking aeroplane in the Mediterranean and showed great bravery in the evacuation of an improvised aircraft carrier when it was ablaze after coming under attack from shore batteries. He commanded a unit of French and British sailors in guerrilla fighting against the Turks then went to Italy after training as a pilot. He was seconded to the Italian Army for whom he organised the first parachute landing of an agent behind enemy lines. The agent later named his first son after Wedgwood Benn. By the end of the war he had been twice mentioned in dispatches and had been honoured by three countries: Britain appointed him to the DSO and awarded him the DFC; France made him a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour and awarded him the Croix de Guerre; and the Italians awarded him the War Cross and the bronze medal for military valour.4 While this was the stuff of which Boys’Ownyarns were made, Wedgwood Benn’s own account in his book IntheSideShows(1919) reveals how this sensitive man discovered ‘what militarism really means: its stupidity, its brutality, its waste. … Is there anyone, now, who will deny that, step by step, warfare degrades a nation? The low appeal succeeds the high. The worst example prevails over the better.’5 While in the services he had refused invitations to return as joint Chief Whip under both Asquith and Lloyd George and had also declined the job of parliamentary secretary to the Munitions Department. His own constituency had been lost in boundary changes under the Representation of the People (Amendment) Act 1918 and, as 4he was not prepared to accept endorsement by the Liberal–Conservative coalition of Lloyd George and Bonar Law, those party chiefs were not going to find him a new seat. Eventually the Liberal Party in Leith invited him to stand against the coalition candidate there and he became one of twenty-nine non-coalition Liberals returned to the House.

Several of these, finding their position exposed, soon went over to the coalition, leaving the ‘Asquithian’ Liberals and the fledgling Labour Party as the only opposition to Lloyd George’s rule. It was in this position as chief organiser of the independent Liberals, or ‘Wee Frees’, that he was able to court his future wife, Tony Benn’s mother.

Margaret Holmes was from a Scottish Liberal nonconformist family. As so often, strength of character showed itself in early rebellions and solitary achievements. She was always a feminist and, against the wishes of her father, would go to meetings of Emmeline Pankhurst and Millicent Fawcett. Somewhat adventurously for a girl before the First World War, she began smoking at fourteen. Then, in 1941, when it might be thought there was more reason to smoke, she decided to stop and did so immediately. No less impulsively, she was inspired to learn Hebrew, when on a trip to Palestine in 1926 she heard Jewish pilgrims singing psalms. Despite the difficulty of the language, she learned it well enough to impress David Ben-Gurion after the founding of Israel and, in recognition of her scholarship, a library in the Hebrew University on Mount Scopus was named after her in 1975.

Her father, Daniel Turner Holmes, was elected for Govan at a by-election in 1911. Margaret Holmes was sitting in the Ladies’ Gallery, visiting her father at the House of Commons, when she first saw Wedgwood Benn, then a junior government Whip. ‘He was very alert and lively, with very fair hair,’ she remembered.6 Eight years later he was helping her father at a North Edinburgh by-election of 1920, Holmes having lost his Govan seat because he had refused, like Wedgwood Benn, to accept the coalition ‘coupon’ which would guarantee victory. But he was defeated in North Edinburgh and moved to Seaford with his family. Wedgwood Benn visited them there on his bicycle, then invited the family several times to the House of Commons. The first time he was alone with Margaret, the forty-three-year-old bachelor proposed in his usual, practical style: ‘Well, we could live near the House in Westminster and you could have a chop at the House every night.’7 Margaret did not like chops, but she was taken with the proposition and they were married on 17 November 1920 before 5a congregation packed with leading Liberals, but from which Lloyd George was conspicuously absent.

The marriage was witnessed by Asquith. On the marriage certificate Sir John Benn was described as ‘Baronet’, a title he had been given in 1914; Daniel Holmes’s ‘rank or profession’ was noted as ‘Gentleman’. The one demand Wedgwood Benn placed on his new bride was that she should become teetotal, like him, because he wished their children to be brought up teetotal. His sister had made a similar demand on her fiancé in 1912. It was a peculiar feature of Liberalism’s close connection with the nonconformist movement that many people in both the political party and the religious denomination had a deep abhorrence of alcohol. David Benn, like his brother Tony a ‘non-proselytising teetotaller’, remarked that being against alcohol in the early part of the century was rather like being against narcotics in the latter part. It was a principled but unremarkable position.

After a honeymoon at which they attended the inaugural meeting of the League of Nations in Geneva, they returned to live in rented accommodation in Westminster. Their first child, Michael, was born on 3 September 1921. ‘He’s going to be a great friend of mine,’ said Wedgwood Benn. The family moved in November 1924 to 40 Grosvenor Road, on the river. It was here that Tony Benn was born on 3 April 1925. ‘Isn’t it wonderful, it’s a boy!’ said Wedgwood Benn. ‘It would have been just as wonderful’, Margaret Benn remarked dryly, ‘if it had been a girl.’8

Margaret Benn gave to the boys, in Michael’s words, ‘the precious gift of religion’. Bill Allchin, a schoolfriend of the Benn boys, remarked that it was in their household that he first heard the phrase ‘ordination of women’, one of Margaret Benn’s great passions. As a member of the League of the Church Militant she was summoned to Lambeth Palace to see Archbishop Randall Davidson. She explained to him, ‘I want my boys to grow up in a world in which the Churches will give women equal spiritual status.’9 She became an Anglican at the age of twenty, before her marriage.10

The twin pillars of religion and politics run through the Benn ancestry up to the earliest-known Benn, the Revd William Benn of Dorchester. A dissenter, he was one of 2000 Anglican clergymen exiled from their livings by the Five Mile Act of 1665, one of the retributions which followed the restoration of the monarchy after the English Revolution.

Wedgwood Benn, often known affectionately as ‘Wedgie’, was involved in the early 1920s in a tenacious struggle as he and a handful 6of colleagues kept the flag of radical Liberalism flying in an increasingly conservative House of Commons. He used to take three copies of TheTimes,one for Margaret and two for him to mark up and file. For these two he bought the ‘royal edition’, costing sixpence and printed on rag paper, which did not age. Using the information in his Timesfiles, by lunchtime he had issued a bulletin on all the major subjects of the day with which his colleagues could challenge the government. They called it ‘Benn’s Blat’. Because of it, and because the Liberal dissidents were by nature challenging souls rather than voting fodder, the Wee Frees had an influence in Commons debates out of all proportion to their number.

Lloyd George was still the leading Liberal, despite abandoning his early radicalism. The first two years of Tony Benn’s life were therefore a time of hectic activity for his father, who was attempting to prevent Lloyd George from becoming leader of the Liberals. With the party at last reforming after the divisive years of the coalition, Lloyd George was the obvious leader, and Asquith moved to the Lords to accommodate him. What he saw as Lloyd George’s lack of principle, and the personal political fund he brought with him back to the Liberals disgusted Wedgwood Benn. ‘I cannot put my conscience in pawn to this man,’ he said. ‘I will have to be a Liberal in the Labour Party.’11

He had long co-operated with the Labour Party, many of whose policies were identical with those of the radical Liberals. Crossing the floor of the House was difficult, for he had too much integrity simply to announce a change of party allegiance in mid-Parliament. Margaret Benn watched from the Gallery as he walked in to the Commons chamber on 14 February 1927 and sat down on the Labour benches. He then went to shake hands with the Speaker before leaving the chamber to resign. He joked in later life that the only political job he had ever asked for was the Chiltern Hundreds, the non-existent post which the British constitution allows a Member of Parliament to apply for but which entails automatic disqualification as an MP.

This was a decision of great bravery. It may be noted that only one of the SDP MPs who left the Labour Party in 1981 had the integrity to resign his seat and let the voters decide whether they still wanted him. Wedgwood Benn was leaving the safe seat of Leith, for which he had been returned in four general elections (1919, 1922, 1923 and 1924). Leith Labour Party already had a candidate, so there was no future for him there. He was losing his MP’s salary (backbenchers had been paid £400 a year since 1912) and had no wish to return to work in the family 7publishing firm of Benn Brothers, which his brother Sir Ernest had made his own domain. Wedgwood Benn could survive on his £500 per year pension from Benn Brothers but he was far from well off in relation to others of similar social status. Most importantly, Wedgwood Benn at the age of forty-nine and with a wife and two young children, had cut himself off from the Liberal Party, without having any alternative power base in a constituency or in the trade union movement.

The decision was a momentous one for the family. His brother Ernest, afraid that his talk of joining the Labour Party showed he had lost his mind, promptly sent Wedgwood and Margaret Benn on a Mediterranean cruise, hoping that a holiday would help him recover his senses. Expecting the trip to last only a few weeks, they left the two boys with their uncle, but Margaret was eager to see the Holy Land, so they disembarked at Haifa, then spent three months travelling through thirteen countries. They had reached Moscow when they heard news of the British General Strike in 1926, and only then were they at last prompted to return. Sir Ernest, fearing revolution, closed his London house and sent his nephews Michael and Tony to the country.

His uncle was a major influence on Tony Benn, for his maintenance of his political principles when all seemed against him. Two years older than William Wedgwood Benn, he stood at the opposite end of the Liberal Party spectrum. Wedgwood Benn was so concerned about public welfare, believing fervently in planning and in state intervention for the public good, that he was virtually a socialist even while he was a member of the Liberal Party. Ernest Benn, on the other hand, was the complete laissez-faire capitalist. He believed that wealth and public benefit could be achieved only by the absolute economic freedom of the individual. In 1925, two years before his brother joined the Labour Party, he wrote ConfessionsofaCapitalist, in which one chapter was entitled ‘Making £1,000 in a Week’. He formed short-lived organisations like Friends of Economy and the Society of Individualists to promote his economic ideas and became a significant public figure on radio and on the lecture circuit. ‘He totally disapproved of the way the country was going,’ said David Benn. ‘He thought the Labour Party was bringing the country down. He would have felt entirely at home in the Britain of the 1980s, though he would not have approved of a woman Prime Minister.’12

Tony Benn always had an affection for his uncle, despite their differences, and the Benn family in general had reason to be grateful to him. It was he who transformed Benn Brothers from a publisher of 8commercial journals into a major publishing house with a list which included H. G. Wells, Joseph Conrad and E. Nesbit. He was an enlightened capitalist; his firm was one of the first two to introduce a five-day working week and introduced a bonus scheme which related an increase in shareholders’ dividends to an increase in salaries for his workers. It was thanks to Sir Ernest that Wedgwood Benn could afford to buy the lease on 40 Grosvenor Road and he always invited the whole family to enjoy the hospitality of his home at Christmas.

Tony Benn’s mother, admittedly a somewhat partial witness, gave this account of his early childhood: ‘He was a most delightful little boy, an unusually friendly little boy, awfully interested in people. He was very companionable – he would sit and play and talk to you and if anybody wanted an errand run you didn’t have to ask him, he was there to do it. He showed for a child such an unusual interest in people. If somebody was ill he was concerned and asked after them. I thought to myself, “Here’s a boy who’s going to make an East End parson.”’13

Margaret Benn remembered Tony learning to speak very early, managing complete sentences almost (or so it seemed) at once. She especially recalled him speaking volubly one dramatic night when the Thames burst its banks and flooded the basement of 40 Grosvenor Road. This was on 6 January 1928, when he was three months from his third birthday. Margaret Benn was awoken in the early hours of the morning by her cook shouting, ‘The Thames is in the house!’ When she looked out of the window she saw that the road had disappeared under the rising water. Two tides had been held back by the wind and there had been a freeze further up the river which had now melted. The tides and the melted ice had met outside their house, so it was here that the Thames burst through, flinging the stone blocks of the embankment aside like toy bricks. She picked up the telephone and the operator advised her to go to the highest rooms and to be prepared to climb on to the roof. ‘I got the children out of bed and Anthony was most interested in everything. He wanted to look out of the window and at the water in the house. I remember our nanny having to tell him he couldn’t have ginger beer even though it was one in the morning.’14 Beatrice and Sidney Webb lived next door and Tony Benn vividly remembers seeing a trunk of theirs floating out of the house on the flood water.

The house was uninhabitable for some time, so the family moved to Scotland, where Wedgwood Benn had been selected as Labour candidate for West Renfrew. Before a general election could be called, 9a by-election was held in North Aberdeen and the West Renfrew constituency party allowed him to stand. He was returned as a Labour MP for North Aberdeen on 16 August.

The family applied to the Norland Institute for a qualified nanny. They sent Nurse Olive Winch, a charming woman of twenty-eight, who was nicknamed Bud, who was to stay with the Benns for twelve years and to remain a family friend for the rest of her life – the next generation, Tony Benn’s own children, were devoted to her. Margaret Benn said, ‘Anthony was brought up under the influence of someone making him want to do what he ought to do and enjoy doing it. I think it’s made a tremendous difference to his whole life.’

Wedgwood Benn called Tony ‘the serving brother’, because of his eagerness to be of help to others. The Liberal-Christian tradition of life as a service was further encouraged in the children, doubtless unwittingly, by household games. Margaret Benn explained: ‘They used to pretend they were workmen called Bill and Jim – Michael was Bill, Anthony Jim. Nurse Olive made them working clothes and they used to come and ask for jobs and I used to give them little jobs and pay them.’15 This game gave Tony Benn the name his family was always to use, his parents humorously making the name more dignified by extending it to James.

The third Benn brother, David, was born in Scotland on 28 December 1928. Soon afterwards the family returned to London. Anthony’s first school, in September 1931, was Francis Holland, a girls’ school in Graham Street near Sloane Square which took boys in their nursery class. Miss Morison, the head, taught him scripture and before long declared that he was the most interesting little boy she had ever taught: ‘To tell you the truth, when I begin he begins.’ This was a reference to Anthony’s eagerness to show off his scriptural knowledge – a knowledge somewhat coloured by his use of political terms to describe religious events. ‘The Sinai pact’ was one of these. Margaret Benn remarked, ‘He was a very religious little boy. I remember when my husband and I set off for a long journey, when we went round the world in 1933, all three boys gave us something to take with us. Anthony gave us a little book of prayers which he wrote himself, for his father and mother in all sorts of circumstances on our travels. I keep it in my jewel case.’16

Congregationalism, the strand of nonconformism which William Wedgwood Benn protested, is distinguished by the emphasis on each congregation making its own decisions about its affairs, admitting of no higher temporal authority. Anyone brought up in that tradition receives 10the democratic message by a process of spiritual osmosis. Tony Benn also absorbed the militancy of the religious message. He said, ‘I was brought up on the Old Testament, the conflict between the kings who exercised power and the prophets who preached righteousness. Faith must be a challenge to power.’17 In the 1970s he was to describe early British socialist thought as deriving, in the first instance, from the Bible.

In 1934 he went to Gladstone’s School, run by a descendant of the great Liberal Prime Minister, which later moved and was renamed Eaton Place Prep School. His early school reports suggested that he ‘talks too much’ and was ‘too excitable’, but they revealed nothing exceptional.

The boys’ pastimes were unremarkable for middle-class children at the time. Tony was devoted to his elder brother and they spent a great deal of time together. Not surprisingly, these two sons of an RAF pilot who were each to become RAF pilots themselves liked to make model aircraft, which they flew in Victoria Gardens. At home the family enjoyed decidedly Victorian evenings, singing along to gramophone records while the young Tony wound up the motor of the machine.

He did not share the dream of most small children to become an engine driver or a policeman. As Margaret Benn said, ‘He has only ever wanted to be in Parliament. It was his only ambition. He used to go to the House of Commons when he was a little boy and sit in the Strangers’ Gallery and watch the debates. And he would say to me, “Dad seems to be very angry with those men.”’18

The general election of 30 May 1929 was the first Tony Benn could remember. As a Labour MP with considerable parliamentary experience, Wedgwood Benn was picked out to become a member of Ramsay MacDonald’s cabinet when the Prime Minister formed his minority government. In the event he was made Secretary of State for India, a difficult office for he had to drive a middle course between those Labour colleagues like Fenner Brockway who wanted Indian independence immediately and the imperialist right, led by Winston Churchill.

Throughout his years in Parliament the house in Grosvenor Road was dominated by Wedgwood Benn’s work. The whole basement was taken up with his political office, which expanded to take more rooms as he engaged more staff and as the files increased in number. His procedure for cutting and filing TheTimesaccording to a decimalised system was soon fully mechanised. Tony Benn used to delight in watching as the marked-up newspaper pages were cut into columns by a guillotine, then rolled by a conveyor to another guillotine which cut 11at right angles, separating out the articles. They rolled on to be backed with glue and then stuck down on plain paper. Tony used to work in the office on Sundays and developed an enthusiasm for collecting and filing information. Perhaps, he later mused, his father spent too much time as a librarian and too little writing up his own experiences. Tony Benn was not to do the same. He made his first efforts at diary writing when he was nine, and fragmentary journals continued until 1963, when a day-to-day diary began.

The family were close and spent time together more often than might be supposed considering the weight of Wedgwood Benn’s responsibilities and the amount of travelling he and his wife undertook (they travelled abroad in 1932, 1933 and 1934). In fact they probably saw more of their children than comparable middle-class families because they did not send them away to school. Nor was Wedgwood Benn prone, as many other politicians were, to spending his time in the drinking clubs of Pall Mall. Moreover the family always ate together. Margaret Benn said, ‘The children did not have separate meal times, except breakfast, which they ate earlier. They had meals with us and the conversation at meal times was all politics, politics, politics.’19

It was a genuinely happy childhood, despite the rising horror of militarism in Europe and the Far East with the concomitant pusillanimity of the democracies. The family talked often about developments such as the persecution of Jews in Germany and the brutal Japanese invasion of Manchuria. The use of gas against Abyssinian tribesmen was an event so immediate to the family it might have occurred in the next street. International affairs were given an urgency for the children, imbuing them with a sense of world community which would never leave them.

There was a substantial age difference between Wedgwood Benn and his children. On one occasion, when he was arguing with his two eldest sons in public, a woman who felt that the old man needed some support remonstrated with his sons, advising them to do as their grandfather told them. It may have been because of this age difference that Tony Benn speaks and acts as if he is the product of a Victorian rather than a twentieth-century upbringing. The family was high-minded in a Gladstonian way, committed to ideals of service, of self-improvement, of elevated dinner-table conversation. Politics and religion were the constant subject of discussion; humour was present, but it was somewhat jocose. David Benn remarked that his father was ‘not at all remote, an extremely lively and vigorous man. He found leisure very depressing. 12He had a way of overworking and collapsing. He got very keyed up when he was to make an important speech and then he would collapse.’ Wedgwood Benn was one of those men who had no internal mechanism telling him to stop work. He would literally work till he dropped and he would berate himself if he had not used up the last ounce of his strength.

‘His vision was strictly political and rather limiting therefore. We had an extremely good political upbringing but rather a poor cultural upbringing. We never went to the theatre, for example,’ David Benn remembered. They were regular churchgoers and the children said their prayers at night, but religion was not a separate, doctrinaire aspect of life. Rather, life was suffused with Christian sentiments. In David Benn’s words, ‘Politics was not a morally neutral profession.’20

The boys’ schoolfriend Bill Allchin remembers Wedgwood Benn’s injunction: ‘The requirements of a moral life are to keep a job list and a cash book.’ Wedgwood Benn tried to encourage his sons to live by these precepts. Tony Benn could receive his pocket money for the week if he accounted to Wedgwood Benn’s secretary for expenditure the previous week. His father encouraged him to keep a time chart showing the way each day was spent. On this he would mark in different coloured pencils the amount of time spent on work, sleep, discussion and other activities. When the lines were joined up it would be a graphic demonstration of the productive use he had made of the hours in a day, a spur to do better in the future. This was a habit he was to keep up until his marriage. As a student, writing about himself in the third person, he described the system which had been started in boyhood: ‘He attempts to organise his life with three mechanical devices. A petty cash account (to keep him economical), a job list (as a substitute for an imperfect memory) and a time chart (to give him an incentive to work).’21 Tony Benn always was a maker of lists and keeper of records.

John Benn, the children’s grandfather, who had died in 1922, had built a cottage at Stansgate in Essex as a holiday home but had sold it in 1902. Wedgwood Benn had always been happy there, so he bought it back in 1933 for £1500. It was there that the family gathered for the birth of Margaret Benn’s fourth child in 1935. Sadly the child, named Jeremy, was stillborn. That night six-year-old David fell ill with bovine tuberculosis. At the time, there was no cure except for rest. He was looked after by Nurse Olive at Stansgate, at her own home in Harlow, Essex, and in Bexhill, where it was believed the air would be good for him. His illness lasted more than three years.13

Wedgwood Benn had lost his seat at the general election of 1931, but he remained with the Labour Party, which had lost office, in opposition to the national government of Ramsay MacDonald. For four years he had no constituency to nurse, until he was selected to stand for Dudley in 1935. The November 1935 election was the first in which Tony Benn could remember working. He campaigned for Kennedy, the Labour candidate in Westminster, distributing a pamphlet called ‘50 Points for Labour’ which he was later to compare favourably with the result of the Labour Party’s policy review in the 1980s. It seemed to him unremarkable that he should be working for the Labour Party, though he remembered calling a cheery socialist message to a workman unloading coal as he walked to school and being struck by the man’s surprised reaction to this young toff’s allegiances.

Wedgwood Benn lost the election, once again finding himself with no constituency to sustain him, though he was now fifty-eight. He could easily have become a man content in late middle age to reminisce, relying on his earlier prestige. He spent some time putting his papers in order and going on lecture tours for the British Council, but it was not enough for his restless energy. Fortunately for him, less than two years later he was selected to fight Gorton in Manchester for Labour at a by-election. He was returned in February 1937 to play his part in the battle against Chamberlain and the appeasers.14

2

Westminster School

Tony Benn entered Westminster School in the autumn of 1938. Some boys were awed by going to school in a collection of buildings with a history stretching back five centuries, over the road from the Mother of Parliaments and round the back of Westminster Abbey. Tony Benn found it much more natural. ‘It was my local school,’ he said. ‘I wasn’t a boarder, I walked there and back every day. The Abbey was just where you went for prayers, Parliament was round the corner, where my dad worked. I’d been there in 1937 after he had won a by-election. I met Attlee and Lloyd George that day. It was my local village really.’1

The Westminster day started with a procession into the Abbey for prayers from 9.00 to 9.20, where the day boys would meet the main school in that mausoleum of famous men. There were the customs and rituals common to public schools: the tombstone in Westminster Chapel floor across which boys must not walk, the gateway where scholarship boys must stand guard while Latin prayers were conducted, the requirement that the first-year boy learn the lore and language of Westminster on pain of punishment, not to himself but to the second-year boy who taught him. One whimsical tradition was the Latin play, a comedy by Plautus or Terence, during which a master would sit with the tanning pole, the stick used to beat boys, on this occasion tied with a pink ribbon to render it less fearsome. When a joke was made on stage this instrument would be waved balefully from side to side to cue laughter.

Michael, three and a half years older than Anthony, was already at Westminster. He was a handsome, popular boy, both athletic and studious and with a deep moral sense, the very specimen the public schools of England wished to produce. Neville Sandelson, a contemporary of the Benns, used to cox for the team in which Michael rowed. He said: ‘He was quiet, modest, personally diffident. He was good. He emanated a 16quality of goodness which made an impression on me then and which I thought about in later years.’2 Michael certainly made more impression in the school records than his younger brother. He was the one who rowed for the school and acted in school plays. In the words of the school archivist, Tony was ‘overshadowed by his elder brother’.3

Physically Benn minor made a strong impression. Various sources remark that, whereas many boys looked idiotic in their top hat and high collar, Tony looked the part of a young aristocrat. Neville Sandelson said, ‘I remember him as being a very good-looking young boy. He had a childish pink complexion – I think of him primarily in terms of pink and white. He was ebullient, garrulous, a little bumptious, a quality I admired enormously.’4 Peter Ustinov in his memoirs called him a ‘joyous little gnome’.5 This garrulous cherub immediately became involved in argument and agitation about international affairs. Donald Swann’s first recollection of Tony Benn is of him distributing leaflets. ‘He had an influence on all of us because he was so full of conviction,’ he said. ‘The balls were in the air. It was obvious Tony was on the brink of a whole lot of things he was going to do with his life.’6

Patrick MacMahon, who was to remain in contact with Benn over the first decades of his life, said of the schoolboy: ‘There was nothing remarkable about Anthony except that he was argumentative. He liked arguing and when an argument turned against him he turned it into a personal matter – he tried to get at the person he was arguing with.’7

There was ample opportunity for argument at Westminster, despite the school’s traditions. Donald Swann remarked, ‘It was a very outspoken, literate school. It was possible to have socialism and pacifism openly discussed. It resembled a university rather than a school.’

Tony was keenly aware of the international events which dominated 1938, the year he entered the school: the Anschluss of Austria by Germany in March and the Munich conference on the future of Czechoslovakia in September. The failure of old-style politics to deal adequately with the great international problems of the 1930s gave heart to young radicals. The atmosphere of political debate in public schools at the time was unequalled in the twentieth century until the school revolts of the 1960s and 1970s. The school’s United Front of Popular Forces, of which about a quarter of the pupils as well as nine masters were members, had collapsed under the weight of its own idealism a few months before Tony Benn joined the school. Its first manifesto statement, ‘Uncompromising Resistance to Fascism, Conservatism and War’8 offered a sample of 17the wealth of contradictions which progressive forces might embrace in the 1930s.

There were clear divisions in the school which were reinforced by the masters. The last period of every day was reserved for ‘Occupat’ (‘let him be occupied’), in which the boys had a choice of doing officer training, physical education or the scouts. Tony Benn joined the scouts, which were led by a pacifist called Godfrey Barber. Benn said, ‘The scouts were anti-militarist. The difference between the scouts and the officer training corps was really a political difference. When the war broke out I left the scouts and joined the Air Training Corps, which had just been set up, and this was seen by Godfrey Barber and some others as a betrayal of a political position, because of their distrust of the uniformed people who were preparing to go into the services as officers.’9

Almost as soon as Tony joined the school there was talk of the first evacuation from London in preparation for the coming war. Europe, it was felt, was sure to go to war over Hitler’s demands for the absorption into the Reich of the German-speaking and heavily industrialised northern segment of Czechoslovakia. Because it was widely feared that devastating aerial bombardment would be the likely first consequence of a declaration of war, the school boarders were evacuated on 28 September to Lancing College on the Sussex coast, whose headmaster Frank Doherty was a Westminster Old Boy. Homeboarders like Tony and Michael went down the next day. Their mother remembered that Michael and Tony took evacuation badly – it was the first time they had ever been away from home.

The Munich agreement of 30 September 1938, signed by the British, French, Italian and German governments, supposedly guaranteed the remainder of Czechoslovakia against aggression, once the Germans had taken a third of the population, together with the territory they occupied. Meanwhile Poland and Hungary enjoyed border adjustments at Czechoslovakia’s expense. The Conservative Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain returned home believing he had obtained ‘peace for our time’, and the international situation was deemed safe enough for the return in two shipments of Westminster boys, on 1 and 3 October.

Whatever the international morality of what Sartre called ‘the reprieve’, it was the occasion for the first public acclamation of Tony Benn’s talents as an orator. The Junior Debating Society held a meeting in October 1938 on the motion ‘This house supports the government’s attitude towards the present international situation’. The school magazine