Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

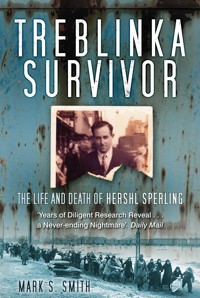

More than 800,000 people entered Treblinka, and fewer than seventy came out. Hershl Sperling was one of them. He escaped. Why then, fifty years later, did he jump to his death from a bridge in Scotland? The answer lies in a long-forgotten, published account of the Treblinka death camp, written by Hershl Sperling himself in the months after liberation and discovered in his briefcase after his suicide. It is reproduced here for the first time. In Treblinka Survivor, Mark S. Smith traces the life of a man who survived five concentration camps, and what he had to do to achieve this. Hershl's story, which takes the reader through his childhood in a small Polish town to the bridge in faraway Scotland, is testament to the lasting torment of those very few who survived the Nazis' most efficient and gruesome death factory. The author personally follows in his subject's footsteps from Klobuck, to Treblinka, to Glasgow.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 616

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For my family and the Sperling family.

Just as the water reflects one’s face, so does one’s heart reflect other human hearts. – Proverbs.

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Preface by Sam Sperling

Chapter One The Bridge

Chapter Two The Book

Chapter Three Poland

Chapter Four Klobuck

Chapter Five Częstochowa

Chapter Six The Plan Unfolds

Chapter Seven To The Gates of Hell

Chapter Eight Ghosts of Treblinka

Chapter Nine Treblinka in History

Chapter Ten The Selection

Chapter Eleven Between Life and Death

Chapter Twelve The Spite

Chapter Thirteen Conspiracy

Chapter Fourteen Uprising and Escape

Chapter Fifteen The Forest

Chapter Sixteen Auschwitz

Chapter Seventeen Germany

Chapter Eighteen Restless and Hopeful

Chapter Nineteen Memory

Chapter Twenty The Search for Life

Chapter Twenty-one Shock Treatment

Chapter Twenty-two The Final Struggle

Chapter Twenty-three The End

Chapter Twenty-four Hope

Postscript: Piecing Together a Life

Appendix Hershl’s Testimony

Copyright

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The writing of this book was most painful to those closest to it. I am grateful to them for persevering with me in what was a difficult, at times lonely and often emotionally draining endeavour. Family and friends were always there to steady, guide and encourage me. I am in their debt.

The largest part of this debt of gratitude, however, belongs to Hershl Sperling’s sons, Sam and Alan. I feared many times that I was probing too deep and reopening wounds that if not fully healed had at least fleshed over, so they might continue to live in this world. But I did probe and reopen their wounds, and they bled willingly, with honesty and courage. My gratitude to them carries with it the unease of knowing they were hurt by the memories they were asked to recall. On many levels, this book is borne through their suffering.

The contribution of Sam Sperling requires its own acknowledgement. His intelligence, gentle criticism and guidance – from the project’s very conception to its conclusion – helped me immeasurably in making this work as honest a reflection as possible of Hershl Sperling. He was an inspiration at almost every stage of the book. It is to him I owe my greatest debt.

A writer also needs time; and I am indebted to the Scottish Arts Council, without whose financial support and belief in the project I would not have been able to take time out from the daily grind to sit at my desk each day and write. I also want to thank Ivor Tiefenbrun of Linn Products, who helped support the project. Leslie Gardner, my agent, stuck it out tenaciously, and I am grateful for her perseverance and belief in the book.

I want to thank Roy Petrie, my travelling companion in Treblinka and Warsaw, for the excellent maps he devised for this book, and also for his encouragement and for sharing the experience with me. I am grateful to Heather Valencia for her translations and Yiddish-language expertise.

I am indebted to my wife, Cath, and to my friend, Chris Pleasance, whose reading of the text in its umpteen stages helped me see my errors, inconsistencies and stupidities. Industrious study of the completed manuscript by Hana Sholaim and Ian McConnell located further errors and inconsistencies that even the most astute and diligent of readers would likely have accepted. The errors that remain in this work are mine alone.

To write this work, many books needed to be consulted. There were numerous sources, chief among them were Martin Gilbert’s The Holocaust: A History of theJews during the Second World War, Jews in Poland by Iwo Cyprian Pogonowski, Revoltin Treblinka by Samuel Willenberg, Trap Within a Green Fence: Survival in Treblinka by Richard Glazer, If This is a Man and The Drowned and the Saved by Primo Levi, Extermination Camp Treblinka by Witold Chrostowski, Into that Darkness, by Gitta Sereny, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps, by Yitzhak Arad, The Origins of the Final Solution: The Evolution of Nazi Jewish Policy by Christopher R. Browning, Memorial Candles: Children of the Holocaust by Dina Wardi, Dachau Liberated,The Official Report by the U.S. Seventh Army, edited by Michael W. Perry, After theHolocaust: Jewish Survivors in Germany After 1945 by Eva Kolinsky, and last but not least, Treblinka by H. Sperling.

PREFACE BY SAM SPERLING

When Mark first mentioned that he would like to write a book about my father I felt both happy and scared. Primarily, my fear concerned whether he would be able to remain faithful to my father’s experience and produce a book that my father would have felt he could endorse, were he still here. These fears were allayed when Mark explained that he wanted to base the hub of the story around my father’s testimony and that he would include the testimony in full within the book. My father’s own account, his own words, would be included and I knew that he would be happy with that.

My next fear concerned whether I would be able to read the book. I have spent almost 50 years finding strategies to avoid the past, and the memory I have of my father’s pain does not really subside as the years go by. Did I really want to focus on these? And then there were fears about how my brother would react. He is ten years older than I, and probably even more affected by the Holocaust’s aftermath.

I found it surprisingly easy to read when Mark sent me the manuscript. I read it, I wept, then it was over. When a few days passed, I found myself wondering about the meaning of the book. As far as any experience has meaning, this struck me as a book that warns of man’s condition. It is a story about prejudice and racism in general and a study of the potential beast within all of us, that could so easily consume us if we do not learn lessons from the past. Sadly, it seems these lessons have not been learned yet. Just as I play mind games that enable me to suspend the past and continue in the ‘here and now’, society does the same. I always remember my father having compassion but I rarely, or never, remember him showing such deep empathy openly as he did when he saw the film The Killing Fields. You see, it confirmed to him that it was not over. The herd could still be manipulated into acts of unspeakable evil, and if we could not learn from the Holocaust what would it take?

Anti-Semitism, the theme of this story, is only one manifestation of this evil. It is an old traditional form ingrained in many cultures, especially within Europe. It lives on in several forms, including within the right-wing fascist politics of hatred. Sadly, in today’s Europe, it is increasingly thinly veiled as anti-Israeli sentiments within many supposedly left-wing organisations, too. I am not advocating that Europe suspend all criticism of Israel or that Palestinians should not have the right to as good an existence as Israelis, but all too often I am found questioning the double standards and motivations of many of Israel’s overly zealous critics.

In all too many cases it is the supposed ‘intelligentsia’ that are at the forefront of this group. Shamefully, they push a myth that says education defeats racism, as if to say they are immune because they have read a few books. They have missed the point. Anti-Semitism, and racism in general, is about what is in your heart, not your head. It is about being decent or not, it is non-discriminating of intellectual ability.

I hope and trust that readers of this book do not see this as an exclusively Jewish story; it is about all people and their right to a free life without any fear of the irrational mob that we are all capable of joining.

Sam Sperling

CHAPTER ONE

THE BRIDGE

On Tuesday morning, 26 September 1989, Hershl Sperling, a survivor of two Nazi death camps and at least five concentration camps, contemplated suicide. He was 62 years old. Strange, at least at first glance, that a man who had survived Auschwitz, Dachau, Treblinka and other hellish places – certainly in part through acts of hope and inner strength – would consider taking his own life. He was, after all, a survivor. He was also a widower, and the father of two adult sons who loved him. He was now in Scotland, far away from his old country and the source of his torment – places that today still conjure up terrifying images of fire and mountains of twisted corpses. Strange also to think that this quiet Polish Jew in the suburb of a faraway Scottish city, this man who had once lived around the corner from me and whose son was my best friend, had witnessed that fire with his own eyes and had dragged into it those twisted corpses. I see him now, sitting at his kitchen table in his house at 63 Castlehill Drive, Glasgow. He winks at me as I enter. I can tell he likes me. ‘Boychik,’ he says, watching me with his pale green eyes that are full of mischief and madness. ‘How are you today?’ There appeared no cause for survivor guilt or shame here. What did he have to feel guilty about? Hershl Sperling had been an innocent victim, not a perpetrator. Yet here he was at the precipice.

That Tuesday morning, there may have been something familiar about the day’s beginning – some strange, lingering echo of that time, 47 years earlier, when his world changed forever. How normal the world was before the Nazis came – children playing, laughing, families working, living, cooking, struggling, loving each other without even knowing it, people simply being. Now thousands of skeletons, all those dead Jews he carried, reached out their bony hands to him– all those children. It is the murder of children that is the stuff of nightmares. In many ways, Hershl Sperling was crazy, and he knew it; but the world was crazier.

Dawn had come dim and dry. This was an Indian summer, at least for Glasgow’s normally dreary climate. Hershl had slept the night inside the old Caledonian Rail Bridge over the River Clyde in Glasgow’s city centre. His previous suicide attempts had been foiled by those who cared about him; this was not the first time he had disappeared to wander the streets of Glasgow, seeking out the company of down-and-outs. As he lay prostrate atop one of the iron girders, deep in the dim netherworld of criss-crossing metal supports and hidden platforms, there approached the haunting sound of clicking metal wheels on the track above him, shocking him out of an alcoholic stupor. The sound gathered pace until it shook the entire structure as it passed overhead and disappeared slowly into the silence of the morning. By 6.00am other trains had begun their deafening rattle across the bridge. Hershl dragged his thin body upright and moved like a phantom through the dark recesses of the bridge. He stepped around the unconscious, oblivious bodies of others who had sought a night’s refuge here, and he climbed down on to the bank of the River Clyde.

Hershl had been one of the Treblinka Sonderkommando – a fifteen-year-old Jewish boy plucked from the mouth of death to become a slave of murderers. To Hershl, the entire world could be explained through Treblinka. The experience could never be forgotten and the wounds that had been gouged could never heal. He had witnessed crimes beyond belief, unimaginable in magnitude. He had also been one of the few who had revolted and escaped; he should have been proud of that. His very existence belied the assumption that all the Jews had gone to their deaths like sheep to the slaughter. Hershl and other escapees had torched the camp on the way out. He had wanted the factory of death to be obliterated. I remember how courage came easily to Hershl Sperling; but courage was not enough to keep him in this world. His final drama, on the streets of Glasgow, remains a testament to those who survived, but whose suffering did not end with liberation.

He wandered now in a haze of drugs and alcohol along the riverbank and through the city streets. Those who saw him likely mistook him for one of the many drunken homeless in this city. Traffic and crowds began to throng the streets. The odour of exhaust fumes from cars and trucks already permeated the air. Diesel and gasoline engines had been used by the Nazis to pump carbon monoxide into the Treblinka gas chambers. He could not forget that deathly stench.

* * *

That Hershl was alive on that Tuesday morning is in itself extraordinary. All except a minute fraction of those who entered Treblinka, let alone Auschwitz and Dachau, were consumed in its gas chambers and flames. Among the random sampling of human beings who were swept together in the Nazi round-ups and sentenced to death, they took a fifteen-year-old boy whom, it seems, could not be killed. Like all survivors, two prime factors kept Hershl alive – good health when he entered the camps and the improbable confluence of unlikely events. He could also be daring, cunning and fearless.

He was raised in a strictly orthodox Jewish home in an old Polish shtetl and had once believed in the innate justice of God and his fellow man. It has been said that when he was young, Hershl was kind, and that he laughed more than most, but what use was joy in the abject degradation of Treblinka, where beatings, cold, fatigue, humiliation and starvation had to be endured each day? It was Treblinka that stayed with him. He survived in part because of hope, inner strength and resourcefulness, but so many victims were just as strong and resourceful as he and had perished.

Many times I walked his probable routes through the city streets during those final days. I tried to imagine his psychological condition and the dreadful memories he carried. What would I have done in Hershl’s place? Would I have survived? Statistically, the odds were massively against, but in the end it is too trite a question.

When I knew Hershl, he was still a kind man and he smiled often, although I also remember him howling in his sleep during afternoon naps. He spoke little of those terrible years – not because he had chosen to remain silent, but, as I came to understand, because he could not express all the horror he had seen nor the magnitude of the loss he felt. Later, when I asked his sons if they thought Hershl would want me to break his silence, one son replied that I was the only one who could. So now, long after the Glasgow rains and the Polish snows have washed away all the tears Hershl shed, I am writing his life. It is, in part, another warning. Hershl knew better than anyone that warnings must be repeated. In a decade from now, there may be no survivors left, and as the years advance the truth deniers and the glorifiers of the Nazis grow in strength. The number of Treblinka survivors alive today, as I write these words, can be counted on the fingers of one hand.

During the afternoon of that September Tuesday, a small article in the GlasgowEvening Times recorded the police search, which had been launched after Hershl’s eldest son, Alan, reported his disappearance. During one of our many phone calls, Alan told me: ‘My father had been absolutely furious in the past when we reported him missing. Police and ambulances had always found him and brought him back. He wanted to kill himself. But, I’m sorry, when a human being is in that state, never mind that he was my father, and he walks out of a house after taking a large handful of pills, gets into a car and drives off, you have to do something.’

The newspaper article noted that Hershl, or Henry as he was called in his adopted country, had been missing since Friday from his home in Newton Mearns, a suburb on the south side of Glasgow. He was described as five feet seven inches tall, with grey, receding hair and wearing a light brown windbreaker jacket and blue jogging trousers. The search, it said, was concentrated around Whitecraigs Golf Club – Jews unwelcome at the time – after Hershl’s car was found in the club parking lot. This place likely served a dual purpose for Hershl: to confuse the search and to confront anti-Semites, even in death. His strategy worked well. Police asked local residents to check their outhouses, sheds and garages for any sign of him. Police and dogs also searched nearby Rouken Glen Park. There are many places in that park where a man could lose himself, or even lie undiscovered for days. But he was not there.

* * *

It was another warm day, exactly 47 years earlier, on 26 September 1942, when Hershl Sperling was packed on to the train that would take him to Treblinka. The Gestapo had discovered Hershl and his family hours earlier, hiding in a bunker in Częstochowa, the Polish city revered by Catholics as the home of the Black Madonna. Hershl spoke of the terrible thirst of the freight car, of the desperate souls crammed in like cattle, and the sweet odour of death that hovered over Treblinka as the train pulled towards its destination. ‘Auschwitz was nothing,’ he used to say. ‘Auschwitz was a holiday camp.’ How terrible was the hell of Treblinka if Auschwitz had been nothing to him?

In the sweltering heat of the boxcar, three days into the journey, the train slowed to a stop just outside the village of Malkinia, seven kilometres from murderous Treblinka. It was a beautiful autumn morning. Hershl pulled himself up amid the crush of bodies and looked through a grate laced with barbed wire. He saw Polish farm workers labouring in the fields beside the train. People called to them from other boxcars. Hershl had recalled: ‘They shout one word at us, “Death”.’

Recruitment into the Sonderkommando of Treblinka was conducted minutes before the doors of the gas chambers slammed shut. Perhaps the most ingeniously vicious crime at Treblinka was the formation of these death camp slave squads. Hershl’s conscription was the unwilling price he paid for survival. These slaves were forced to operate the extermination process. They maintained order among new arrivals, cut women’s hair, extracted gold teeth from the mouths of the dead, sorted the belongings of the murdered, removed the dead from the wagons and gas chambers and dragged them to the pits where their corpses were turned to ash. Yet the gift of life was intended only as a temporary reprieve, because they were also the keepers of the terrible truth. The SS was diligent in ensuring that the mass murder of European Jewry was kept secret. Their Jewish slaves knew everything and so were ultimately destined to share the fate of so many others.

Hershl’s contemplation of suicide 47 years later begs yet another question: had he known then that his torment would outlive Treblinka itself, would he have tried so hard to live? Hershl had spoken of Treblinka’s culture of death. In the barracks, death became a form of resistance. How could he forget the nights and the cries in the darkness of ‘yetz’ the Yiddish for ‘now’? One man, who could endure no more, climbed on to a wooden crate with a noose around his neck. Another man, in an act of friendship, kicked away the box from under his companion’s feet. Death was everywhere – in the barracks, on the trains, on the ramp, in the camp courtyards, in the gas chambers, and in the fiery pits, the source of Hershl’s nightmares, where the dead were dumped and burned.

Sometimes Hershl laid out old photographs of dead relatives on the kitchen table at his home in Glasgow for his sons to see. He spoke about his mother and father and his younger sister, but he never mentioned their names. Then he would begin to cry and leave the room. Did he feel that he did not deserve to be alive, in spite of what he had come through? There must have been guilt that he was alive in the place of others, and that he was not worthy. In the days before he climbed into the bridge, he had told one of his sons that his suffering now was ‘worse than Treblinka’.

* * *

The police search was also conducted in the Scottish seaside towns of Ayr and Prestwick, where, the newspaper said, ‘Mr. Sperling often visited’. This was true. In Ayr, he would walk along the pier and stare out to sea. The last time Hershl had disappeared, he was found in a hotel room in Ayr, drowsy from whisky and pills. He had also been found and returned by police after previous disappearances in nearby Prestwick. Once, years earlier in Germany, he had vanished for almost three weeks, but had come home of his own volition. Hershl was trying to foil the police as well as the inevitable search by his two sons. He did not want to be found.

The newspaper article’s personal description made no mention of the blue-black number – 154356 – tattooed on Hershl’s upper arm, a mute reminder of his year in Auschwitz. Hershl had been puzzled about the number, which had been imprinted unusually on his inner bicep, instead of the forearm where most Auschwitz prisoners had been tattooed. He always said there was something strange about the tattoo, not so much the number itself, but its position, and that other prisoners who had been similarly marked on the upper arm had also survived the camps. Perhaps the number’s position had something to do with his contact with the infamous Nazi Angel of Death, Dr Josef Mengele, he had conjectured years earlier. Yet how could his survival and the number be connected when Mengele killed so many of his patients? Hershl said he had once looked into the eyes of Dr Mengele. Several times he recalled a prisoner who had returned castrated from a session with the Doctor.

Hershl would have been sixteen then, and in truth we will likely never know what Mengele did to him, or planned for him, if anything. Nor did Hershl really understand why he had lived through the camps. Over the years, he tried to find out about the unusual position of his tattoo, but he was unsuccessful. He had once met other similarly marked Auschwitz survivors in New York in the 1960s, but they had no answers either – they were equally confounded by their survival and the position of their tattoos.

Instead of the outhouses and sheds around Whitecraigs Golf Club, and instead of Ayr, Prestwick, or Rouken Glen Park, Hershl walked from the golf club parking lot, his mind already heavy with Valium and Amitriptyline. It was late afternoon. The traffic on Ayr Road, the main thoroughfare through Newton Mearns and Whitecraigs, was heavy as usual that day, and he walked the half-mile to Whitecraigs train station, where he purchased a ticket and boarded a commuter train to Glasgow’s city centre.

Train journeys had long punctuated Hershl’s existence. On his journey from the Częstochowa ghetto, in a stinking boxcar, he would have seen familiar station names rolling past – Radomsko, Piotrków, Koluszki. Hours earlier, he had witnessed savage attacks on his neighbours. People were dragged from the ghetto, beaten and shot. As a desperate escapee, a train had taken him away from a village some 40 km from Treblinka to Warsaw. He was one of the few Jews to see the Warsaw ghetto in ruins after the uprising. Another train had taken him from Warsaw to Auschwitz and from Auschwitz to Birkenau and, close to death, from the station at Gleiwitz to concentration camps at Sachsenhausen, Dachau, and Kaufering less than a year later. A train took him back to Polish soil after liberation, when life was hopeful again, only to encounter anti-Semitism of such fury among his former neighbours that he fled. While waiting for another train to carry him back to Germany, he met his future wife on a station platform in Czechoslovakia, and together they would take a train to the Hook of Holland, and later he would board a boat alone and another train that would take him to a new life in Scotland. Now he was on his final train journey.

The locomotive pulled into Glasgow Central station. Did he recall the boxcar door sliding open at Treblinka, the blinding light, when the train finally arrived? Did he recall the truncheons and hear the savage cries of ‘Raus’? Most likely he exited Glasgow Central by its main entrance on to Gordon Street with the bulk of the crowd, and disappeared into the throng of shoppers and workers. Whether he first wandered the streets of Glasgow or if he went directly to the rail bridge, we do not know. For weeks now, his had become a world of death and phantoms. Certainly at some point he turned south and began to walk toward the river. He crossed the Broomielaw, the street running parallel to the northern bank of the Clyde, traversed one of the pedestrian bridges that span the river and then climbed into the iron rail bridge to spend the night. In limbo between life and death, he listened to the screams of trains as they passed above him.

Today you will find the same paved esplanade and railing. In spite of the attempts to regenerate the city’s riverside areas with upmarket apartments, shiny office blocks and street clean-ups, this south bank of the river has remained dingy. As night falls, the vagrants descend. Hershl’s final nights were spent among the city’s drug addicts, alcoholics, homeless and the mentally ill.

Hershl’s mental health had deteriorated sharply in recent months. In the weeks before, he seemed to slip gradually into the world of the muselmänner, a word used in the camps to denote the submerged, those human beings irreversibly beaten to the precipice of death. In the camps, muselmänner were those who had resigned themselves to death. The origin of the term remains unknown. One explanation is that these victims were so called because they often had bandages wrapped around their heads and took on the appearance of Muslims. Like Hershl, they no longer spoke. In Treblinka, Auschwitz and Dachau, Hershl had seen these emaciated walking corpses. Often muselmänner were clubbed mercilessly to death or they simply dropped from exhaustion. It is possible that Hershl’s unfulfilled need to tell the world of the horror and his own loss had driven him in the end into the condition of a muselman.

In spite of the emptiness in his eyes, and the drugs and the whisky in his blood, Hershl’s mind was far from empty. He had plotted to frustrate all attempts to find him, at least long enough for him to do what he had to do. He had come to this point with purpose. He had sought out the company of tramps in the past, and it is possible he knew when and where to come for shelter after dark, where his night-time, half-delirious and pained cries in Yiddish would not be disturbed, or even regarded as out of the ordinary. The day Hershl left home, sunset in Glasgow fell at 7.03pm. In northern Poland, at the site of Treblinka, it was at 7.24pm.

The time before the war was not so far away for Hershl Sperling, except his memories of happier times were painful – the life he had had with his mother and father, his red-haired sister, the town, his house, their animals – all gone now. Hershl had cried for his family, and all those others who were smoke. He had spoken of the shoes and the ashes, the terrible smell of burning bodies and the clothes and the yellow stars. In Treblinka, he had been forced to sort through the clothes of the dead. He was also assigned the job of opening the boxcars and, because of his ability to speak fluent German, Polish and Yiddish, to translate the orders of the SS men. After the victims disembarked, he cleaned the putrid wagons. He removed the bodies of those who had died en route and dragged them to the burning pits. He had spoken of these things as if he were the only one who knew of them, and the only one alive to care about them. There was a small lace-up boot – belonging perhaps to a child of five or six. There was a large man’s shoe, a young woman’s shoe with a high heel, a child’s coat. What had become of those shoes and coats? He could never forget how the bodies had started to rot and stink beneath the earth in the mass graves nor how the Nazis had exhumed them, all the people who had owned those shoes and coats he had been forced to sort. He could not forget the corpses that were cremated on giant iron grills above the pits.

An article in a later edition of the Glasgow Evening Times updated the story. Police divers were called in as ‘fears grew for the safety’ of Hershl Sperling. It said police had already conducted extensive searches of Whitecraigs golf course without success, and that the search had been extended to nearby Rouken Glen Park and Deaconsbank Golf Club. The searches in Prestwick and Ayr were also being stepped up and police officers in the two towns had joined the hunt.

We do not know if he left the bridge the following day to wander through the city, or whether he remained. We know that he was there, probably lying across one of the girders, in the middle of the afternoon.

* * *

At 4.00pm, on Wednesday 27 September 1989, George Parsonage, the sole lifeboat officer of the Glasgow Humane Society, received a call from the city’s police. A body had been observed floating in the shallow part of the river, just under the Caledonian Rail Bridge. Mr Parsonage rowed to the scene. ‘I always row to these kinds of incidents,’ said Mr Parsonage, who in four decades has dragged more than 2,000 bodies from the River Clyde, some 1,500 of them alive. I met him at his house on Glasgow Green in the summer of 2007. The river flowed fast over a weir a few yards in front of the house.

‘A motor boat creates waves,’ he said, ‘and maybe, just maybe, there is a pocket of air in a jacket that can keep a person afloat and maybe alive.’ Then his face darkened. ‘I saw him lying face-down on the south side of the river, in about two or three feet of water as I rowed toward him. Men nearly always sink, unlike women. So, for a moment, I thought he might be alive. When I reached him, I turned him over, with his back to the boat, and pulled him on to the gunwales. I had to decide there and then whether to try to resuscitate him with mouth to mouth, but now I could see he was dead.’ I asked him if he could tell how long he had been dead. ‘I’d say maybe half an hour,’ Mr Parsonage replied.

‘I searched his pockets for identification. He was wearing a jacket, which I took off him. It was then I saw the number. I was utterly shocked. I realised that man in the water had been in Auschwitz. To think what he had been through was unimaginable.’ He looked directly at me. I could see his eyes water. ‘He had my respect. And what kind of society are we living in, when we let this happen to a man like this, who had been through what he had? I’ve never forgotten him.’

Mr Parsonage, who possesses an optimism that perhaps can only come with the kind of work he does, added: ‘We cannot be sure it wasn’t an accident. Personally, I don’t believe in suicides. I have yet to encounter a suicide that didn’t cry for help when he hit the water. Therefore, at the moment of death, it is no longer a suicide. It was clear the man had come off the bridge. But if he were lying on one of the girders, it would be easy to fall, either if he was sleeping or drunk. There is a big possibility he was sleeping and fell off the bridge.’

Indeed, Hershl had been drinking, and he was also taking large doses of Valium and Amitriptyline. He could swim – according to his sons he could swim well – but the intoxicants may have rendered him unconscious. I later put Mr Parsonage’s theory to both Hershl’s sons. His younger son, Sam, said: ‘I don’t think he had any intention of coming home again.’ Alan agreed.

The following day, two brief paragraphs reported the conclusion of the police search for Hershl Sperling: ‘The body of a missing Newton Mearns man was today recovered from the Clyde in Glasgow. Henry Sperling, 60 [he was in fact 62], had been missing since last Friday.’

In the end, the survival of Hershl Sperling was no survival at all. He wanted his mind to stop. The suffering that began 47 years earlier had continued for the rest of his life, forcing him each day to relive the punishment that the perpetrators had inflicted upon him.

But this was not the end. In 2005, I discovered Hershl had left behind him a hidden legacy that would reveal the truth about his survival and his death, a story that otherwise would surely have been lost. He had dared to put pen to paper in the months after his liberation, a raw truth in a written record of the things he – and all those who could no longer speak – had witnessed.

CHAPTER TWO

THE BOOK

The quest to understand Hershl Sperling’s fate begins with the rediscovery of a secret and long-forgotten book. This was one of his most guarded and valued possessions. He kept it in a brown leather briefcase, which always remained in some out-of-the way cupboard, far from the reach of children or anyone else who might intrude into his world. In this book lay the terrible truth – not just about Hershl himself and what he had been forced to endure, but the truth about all people and what some of us are capable of. The American artist John Marin once wrote: ‘Some men’s singing time is when they are gashing themselves, some when they are gashing others.’

For more than 45 years Hershl kept the book beside him wherever he went, from country to country – and there were many such moves in his life – from home to home and place to place. In spite of the book’s dreadful contents, it comforted him because it was evidence of what had truly occurred, and the truth was all Hershl had to live by. Its contents were as real as the voices of his tortured dreams. If he cried out while napping in the afternoon, his wife would run to his bedside and whisper comforting words in Yiddish. I remember the intensity of her voice as she pleaded with him to come back; he was always disoriented after these bouts. The book, with its pale green cover, the same colour as Hershl’s eyes, held the secret of those nightmares. It was written in Yiddish in Hebrew script, and was published in Germany in 1947, some fifteen months after liberation. No-one inside or outside his family was permitted to look at it and few knew of its existence. Hershl’s wife was among the few to know the book’s contents. I was aware of Hershl’s obsession with the contents of the briefcase, but only because my friend Sam had told me. I knew no more and I dared not ask.

We were a family of Americans in Scotland and we lived around the corner. Hershl liked Americans because they had liberated him in April 1945, as their armies swept through Germany toward Berlin in the final weeks of the war. Our shallow roots in Scotland were on my mother’s side. My great grandmother had been a teenager en route from Riga to New York in the late nineteenth century when the steamer captain hoodwinked her, and a few hundred other Jews, into thinking she had arrived in America. The ship had in fact stopped at the Scottish port of Greenock. It was a common enough ruse among the captains of shipping companies that allowed them to take on more passengers. My great grandmother was a lone Jewish girl from a Latvian farm, and she did not know New York from a piece of apple strudel. My Scottish-born mother, who had emigrated to the US in the 1950s, got homesick some seventeen years later and the family moved back.

Hershl and Yaja Sperling, both of them orphaned by the Holocaust, lived then in their house at 63 Castlehill Drive, Newton Mearns. I remember Yaja as a beautiful and stylish woman in her forties, always impeccably dressed, smiling and kind. Her hair was jet black and her eyes were a deep, dark blue. She worked as a manager at Skincraft, an upmarket leather and suede retailer in the centre of Glasgow. I remember thinking then that was an ironic name for a store for a Holocaust survivor to work in. Even then, I was vaguely aware of macabre atrocities in which the skin of murdered Jews had been fashioned into ornaments. The source of that, although I did not know it, was Ilse Koch, the wife of the commandant of the Buchenwald camp – Ilse is infamous for ordering the manufacture of furniture out of human skin and bones, including skin lampshades. The so-called ‘Bitch of Buchenwald’ committed suicide by hanging herself at Aichach women’s prison in 1967. The Sperlings would not even purchase a throwaway plastic pen if it had been made in Germany.

Yaja Sperling was devoted to her family. She loved her husband profoundly and was enormously proud of her two children. Neighbours remarked that she and Hershl behaved like teenagers in love. They held hands and each evening after their meal they strolled through the neighbourhood arm-in-arm. I remember my father saying, almost every evening at around 7.00pm, as he looked out of the window: ‘There go Yaja and Henry again.’ In their house, when she would put down his lemon tea in a glass after dinner, I remember her smiling at him. It was an intimate moment. She never tired of caring for him. Yaja was Hershl’s anchor, and I remember they loved each other with a painful tenderness and a secret passion.

She was born Yadwiga, or Jadwiga, Frischer. Jadwiga, a strange and jarring name to western ears, had been a popular name for centuries among Jewish girls in Poland ever since Jogaila, the Grand Duke of Lithuania, married the Polish Princess Jadwiga and was crowned King of Poland in 1385. She was one of at least seven children in a poor family from an unknown village near Warsaw, an obscure little community of religious Jews and Polish peasants. Her father, who had remarried after the death of her mother before the war, was a cobbler. Little else is known about her early life. She was ten months older than Hershl. When the Nazis came to her village, she began a tortuous journey through an unknown number of work camps. Almost six years later, she was liberated by the Russians and trekked westward over the Tyrol mountains, where she ate grass and drank snowmelt to stay alive. We do not know the names of the camps in which she was interred or what work she had been forced to perform in them. One of her brothers emigrated from Poland to Israel in the 1950s, but the remainder of her family, save another brother and one older sister, were murdered. She never spoke of those who had perished.

Her sons say Yaja lived in a world of fantasy, where there were no Nazis and no Holocaust. Unlike Hershl she did not dwell on the past, but rather willed herself to obliterate it from her mind and in this way she survived beyond liberation. Hershl could not forget and, perhaps, it was his suffering that helped her forget her own. People said it was she who kept her husband in the world of the living. Just as there exists a hierarchy of suffering among survivors – some camps were worse than others – the same hierarchy prevailed in the Sperling household. Yaja had not lived through Treblinka; she told her sons, ‘I didn’t suffer like your father.’ A photograph of her after the war shows her triumphantly holding a baby over her head outside the gates of an unknown forced-labour camp. If a single image had to be chosen to commemorate Yaja Sperling’s sense of survival, it would be this. More than a celebration of life, it was a victory.

Not that the Holocaust had left her unaffected; the pair established a winking complicity. They took absurd risks together. On one occasion they stole a large mackerel from the buffet of the Danish Food Centre, a restaurant that had recently opened in Glasgow. When they were certain no one was watching Hershl stuffed the entire fish into Yaja’s handbag. Food-obsession was something they shared with other survivors and their kitchen cupboards always contained enough canned food supplies to ensure the family’s survival for at least three months. Sam said: ‘They behaved as though they were preparing for a siege.’ Food symbolised life and death for them. The theft of food was rampant in the camps, both among prisoners and guards. Guards stole prisoners’ food and sometimes killed prisoners whom they suspected of stealing food. In the camps, where all else was stripped away, hidden food equalled a life prolonged. Hershl often stole small things from shops. Whether this was habitual or intentional thrill-seaking it is impossible to know.

To begin with, I regarded Hershl and Yaja just as Sam’s slightly crazy parents. Before long, I had become a regular visitor to their house and at their kitchen table, a guest in their incongruous world of kosher food, Yiddish conversations and bouts of madness. Hershl had long-since abandoned his belief in God, for he had been a witness in places where God could not exist. Yet the Jewish motif of ‘sanctifying God’s name’ – the willingness to sacrifice one’s life in the cause of moral principles – ran like a thread through Hershl’s being and must have made his Treblinka experience all the more painful. Yaja saw the beauty of God in everything.

As parents, they granted their children extraordinary freedoms. They rarely said no. I remember drinking beer for the first time at 14, sitting with Sam at his kitchen table, his mother washing dishes and watching us with a wry expression. Hershl once demanded a meeting with the headmaster of Sam’s high school, a particularly dull and authoritarian man, and warned him never to lay a finger on his son. It was the 1970s, when Scottish school children were belted for misbehaviour, but the headmaster heeded Hershl’s warning. A man who had looked Josef Mengele in the eye was not going to be intimidated by an over-zealous school master. I remember my mother saying, ‘They have a right to be crazy.’ I also remember Hershl yelling Yiddish joyously at his wife, who would laugh. He would then turn good-naturedly to torment and tease his children with crazy word games. Deep within him, there ran a natural love of language. I did not realize then, but it was a clue.

Besides his native Yiddish, Hershl spoke good Polish and German, as well as some Russian, and later English. He also spoke an archaic Hebrew, learned faithfully in synagogue class as a child. Language came easily to him, and it was a gift to which he owed his life. In Treblinka, only German speakers were selected for the Sonderkommando. Those who spoke further languages increased their chances of survival because they might become useful translators for the Nazis. In Auschwitz, Dachau and the other camps, those who did not understand the language of the masters were quickly brutalised and murdered, because they were useless. They could not understand the tirades of the SS or the kapos. Hershl’s fluency in Polish – and many Jews there spoke only Yiddish and just a few words of Polish – had also been crucial and meant survival and opportunity in the aftermath of Treblinka. Yaja also spoke good Polish, and occasionally she and Hershl spoke it in the home – usually for the transmission of things they wanted to keep from Alan and Sam, who understood Yiddish and English very well. Both Sperling children inherited their father’s language gift. I remember one evening sitting down with the Sperlings in their living room to watch Call My Bluff , the television game show in which contestants guessed the meaning of obscure words. Alan, a highly intelligent individual with an expert knowledge of Latin, deciphered every word, a rare feat. But Hershl would always correct him on the Slavic or Germanic pronunciations. And instead of congratulating Alan for his effort, Hershl instead would throw cushions at him and little hard-boiled sweets that were always heaped in a glass bowl on the coffee table, until the room was in chaos. Hershl often behaved more like a child than his children, perhaps because his own childhood had been lost.

There was also panic in their house; but I saw little of that. The outside world was perceived as threatening and frightening. The source of that fear was the memory of the Holocaust, and their behaviour was based on the belief that some future catastrophe might catch them unawares. Every minor incident became a crisis. Sam told me later: ‘We lived as though the Gestapo were about to knock the door down.’

Sometimes crises were entirely invented. During one terrible bout of depression, Hershl became convinced Yaja was having a secret love affair. Alan told me: ‘He was going through a very difficult period, and he accused her, over and over again. It was complete nonsense. She was utterly devoted to him. If she were being accused of robbing a bank, that would have been more probable.’

I remember another time I was sitting with the family in their living room. Hershl sipped his lemon tea, and we were watching a wildlife programme on television. A pack of hyenas squabbled over the remains of a carcass. ‘So much like humans,’ Hershl said, suddenly. ‘We lived like that.’ Sam asked him several times to tell him what it was like in the camps. He was desperate to know. ‘We lived like animals,’ Hershl said. That was all. Later, as if by way of explanation, Sam told me ‘My father was in Treblinka.’ The name meant nothing to me then, because I was hearing it for the first time.

Hershl Sperling had other names. In the shtetl of Klobuck, the little town in Poland where he was born, he was Hershl Szperling, the Polish rendition of Sperling, which is also the German word for sparrow. To his relatives and friends then, he was Hershle, the extra ‘e’ added as a Yiddish inflexion of endearment. But outside the shtetl, in Polish Klobuck, he was Henick, his Polish name. In Scotland he was Henry, except to his wife; at home, and to himself, he was Hershl.

Hershl kept many secrets about his past. His children could not understand whether he was protecting them or himself. The truth is probably that he was doing both. Yet, at the same time, he transmitted his suffering to them, his helplessness and his humiliation. On rare occasions, he would talk chillingly about the Treblinka burial pits, about how he had to go into them. Once, during a trip to Israel, he had watched Sam, then about eighteen, playing a game with his nine-year-old cousin. Sam recalled: ‘He started to say that she reminded him of his sister, but then he became very upset. He started to cry and went inside. We still don’t even know his sister’s name.’

Yaja was the only one who could calm him, but she could not cure him. Psychiatrists could not help him either, nor could the anti-depressants or the other treatments they tried. They did not – could not – understand that ‘Auschwitz was nothing’. They could not possibly understand that Treblinka was not a concentration camp, and as terrible as those places were, they were not death camps. In Treblinka, Hershl had been forced to participate in the systematic murder of at least 700,000 people. Doctors did not know about the pits of burning bodies or what suffering it was to toil among them. Alan said, ‘He witnessed things that people are not intended to witness.’ In Auschwitz, Hershl was beaten by murderous kapos and he spent weeks up to his chest in icy canal water, but it was Treblinka he relived each day. Throughout his life, Hershl insisted that ‘the real horrors’ of the Holocaust were not known – but he knew. Years later, doctors diagnosed mental illness but in fact he was profoundly traumatised.

Sam, desperate to understand, once asked his father if he had killed anyone – the worst crime his young mind could imagine – but Hershl said he had not. He later told Sam that after the war he had been driven by a terrible desire to take revenge on the Germans for what they had done. He wanted to murder indiscriminately, but he chose to take no action. He had preferred to remain as he was, even in his shattered state, than to become like those who had tormented him and had attempted to annihilate an entire people. In the end, Hershl Sperling was a moral man.

When Yaja became ill and died of cancer, Hershl’s manic mood swings grew more pronounced and his disappearances grew more frequent and more prolonged. Studies of Holocaust survivors in Israel suggest that the loss of a spouse can reactivate Holocaust terror and increase the likelihood of suicide. Hershl and his wife had clung to each other in desperation and mutual dependence, and then she was gone.

A month or so before Hershl’s suicide, he sat motionless in his living room chair. He had almost entirely given up food. His eyes were still and stared blankly forward. His head did not move. His body was limp. He reacted to nothing. Sam recalled that he had thrown accusations at him that day. ‘I said things like “See what you’re doing to us. You should never have had children. You should never have brought us into this world”.’ In a brief flash of recognition, he looked at his son and said, ‘You’re right.’ Then he was gone. Those were the last words he spoke to Sam.

* * *

In April 2005, as the world’s media commemorated the sixtieth anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, I was on the telephone to Sam, who was living in London. He had recently given up high-paid employment as a software consultant, and at 45 years old had taken up physics as part of a science degree. Like his father, he had long since given up on believing in God, but retained a fascination with creation and how the world worked at its most fundamental level. He described himself as an ‘agnostic’, because it was ‘impossible to be sure one way or the other’. Hershl had been dead for almost eighteen years. He would have been 78 years old. Sam and I were talking about the Auschwitz commemoration, when he said: ‘Well, you remember what my father always said. “Auschwitz was nothing”.’

‘I remember,’ I said. There was a long pause. I could tell he was biting his bottom lip, as was his habit when something disturbed him. ‘Did you know he wrote a book about Treblinka?’

‘No,’ I said, intrigued. ‘Where is it? Have you seen it?’

Sam had seen the book only once. It was published just after the war, while Hershl was still in Germany, in a displaced persons camp in the American Zone, he said. He recalled that it had ‘horrible pictures in it’. Hershl had become angry when he discovered his son had taken down the leather briefcase and had glimpsed the Hebrew script and the pictures in his book. ‘He was trying to protect you,’ I said.

‘I know. He kept it in that leather briefcase, along with a strange South African seal,’ Sam said. ‘No one was ever allowed to look at it.’ Later, Hershl told Sam he should read it when he was older. But he never did.

‘Do you think he meant for you to look at it?’ I asked.

Sam took a deep breath. ‘I don’t know. Maybe. My brother sent it to a Jewish library somewhere after he cleared out my father’s house. Neither of us at that time really could bear to know what was in it. I’m not sure I could bear it now.’

‘Do you know which library?’

‘No, I don’t.’

‘Could you translate it if we found it?’

‘My parents spoke to me in Yiddish and I answered in English. I can’t speak it very well, never mind translate something.’

‘Should I try to find it and get it translated?’ I asked. There was another long pause, marking a conflict between curiosity and dread that was almost palpable. I sensed menace in his father’s book, and perhaps he did too. I imagined Sam’s hands trembling and I remembered, strangely, Hershl winking at me. I understood then the terrible hold Hitler’s madness had on my friend, even though had been born fifteen years after the beast was slain. I also realised that if this was diluted, second-generation pain, Hershl’s suffering must have been a thousand times worse.

‘All right,’ Sam replied.

So began the search for the book that would reveal Hershl’s secret – the source of his nightmares, and also the source of suffering for Sam and Alan. I had no idea if it would help them, but both were eager for me to proceed. Nor did we have any idea what to expect. I also wondered how such a work could have been published in Germany after the war. Where did the publisher even find a Yiddish printing press in a country devastated by the Allied onslaught and for more than a decade stripped by Hitler of all things Jewish? Did the Nazis not smash Jewish printing presses all over Europe? And then there were the bigger questions. Why had he written it? What horrors would it tell? He was just nineteen years old when he put pen to paper to schreibt and farchreibt, the Yiddish exhortation to write and record.

Phone calls and emails followed. Within a few days, I discovered that the book had been sent by Sam’s brother to the Wiener Library in London, one of the world’s largest collections of material relating to the Holocaust, anti-Semitism and the rise and fall of Nazi Germany. A few days after my inquiry, an email arrived from librarian Howard Falksohn, who had tracked the book by locating the ‘Thank you’ note from the library to Sam’s brother, dated 26 October 1989, one month after Hershl’s death.

Falksohn wrote that the library had been grateful for the book, and that it had been catalogued in the Wiener’s miscellaneous journals series. Its title was Journal of theJewish People During the Nazi Regime. The book, in fact a journal, was Number Four in a series, and was published in March 1947, in Munich, by the Central Historical Commission of the Central Committee of the Liberated Jews in the American Zone. I immediately telephoned Sam. ‘I found it,’ I told him.

‘Mazel tov,’ he said, but I sensed trepidation in his voice. We agreed that I would come to London, that we would go to visit the Wiener Library together and photograph the book. Photocopies were not allowed because of its fragile condition.

Sam chain-smoked cigarettes. He was nervous. His father’s pain had long been his pain. We walked toward the Underground near his home in north London, and he said: ‘You remember Pigpen in the Charlie Brown comics, with that dust cloud always around him wherever he went? That’s the way I felt for a long time, always dirty from the Holocaust, always tainted.’

We got off at Great Portland Street and walked five minutes to the library, hardly exchanging a word. Outside, about 11am on a Saturday morning, Sam puffed nervously on his cigarette, leaning for support on the Victorian railing that led to a grand black door of the old brick building.

‘Are you going to be all right?’ I asked.

‘I don’t know. I think so. Actually, I don’t know what I’ll do when I see the book. Maybe I’ll do something crazy, like eat it.’ We rang the buzzer. I stated our business into the intercom and we entered. Howard Falksohn was expecting us. He stood up to greet us from his desk, and shook our hands.

‘So, the book,’ he said, pulling it out of a brown Manila envelope. He handed it to me and I passed it to Sam.

‘My God, that’s it,’ said Sam, running a hand over the faded green cover, its large Hebrew type drawing attention to itself. In roman type at the bottom, it read, ‘Nr. 4’ and the date ‘1947’. Sam bit his bottom lip.

‘Can you read any of it, the Yiddish I mean?’ I asked.

‘Just a few words,’ Sam said. He opened the book carefully at a random page and looked into the Yiddish text. I saw his hands trembling. ‘Look, that word is ‘krankeyt’ – sickness or illness – but, no, I couldn’t translate this.’

He slowly flipped the book over. On the back, there was an English title: ‘From the Last Extermination’ and a sub-heading ‘Journal for the History of the Jewish People During the Nazi Regime’. I ran my fingers over the cover, touching history, but also touching something terrible, the result of almost unspeakable evil.

Israel Kaplan, the book’s editor, was listed. There were few other clues, at least to the untrained eye. On the inside back cover, a date, March 1947. A Munich print shop was named: R. Oldenbourg. We could make out the Yiddish words, Tsentraler HistorisherKomisiye, and below that in English, ‘Copyright by Central Historical Commission, Munchen, Mohlstrasse 12a. Edition: 8000 copies’. At the very bottom, a small line of print read, ‘Published under DP-Publications License US-E-3 OMGB. Information Control Division.’ There was information here that could be investigated.

A typed note, part of the library’s cataloguing system, stated in Yiddish: Fun LetztenHurban, the journal’s title, and the dates ‘1946–1948 (discontinued)’. It noted this was book number four and had been published in March 1947. This was one volume in a series of eight publications but the library only had one. It also noted: ‘Good condition. Important DP publication. Scarce.’

The library note heartened us. It was important that the book’s value was recognised – but it was not what we expected. A table of contents ran below the title on the back cover page. It appeared to be a list of separate articles written by different individuals on various aspects of the Nazi regime, the murder of Jews and the annihilation of their communities – ‘The Extermination of Jews in Eastern Galicia’ By Dr Philip Friedmann; ‘Polish Jewish Soldiers as War Prisoners (Memoirs)’ by Mendel Lifschitz; ‘Tchernowitz (Cernauti)’ by Dr Jakob Ungar; ‘In the Forests of White Russia (EyeWitness Report)’ a) ‘Around Woloshin’ by Mosche Mejerson, b) ‘In the Braslav area’ by Mosche Trejster, c) ‘At Radun’ by Lieb Lewin; ‘My Experiences During the War (From the Series of Children’s Reports)’ by Daniel Burstin; ‘Lullaby (Ghetto-song)’; ‘Buna (Camp song)’; ‘Nazi documents with comments; photographs of the Nazi period’. The name Buna chimed with me. It was the largest sub-camp of Auschwitz and the place where chemist and author Primo Levi had spent 11 months as a forced labourer. Levi’s suicide in 1987, two years before Hershl’s death, baffled some who knew his work. My scant research to-date had revealed that while suicides are rare amongst survivors, those who wrote of their experiences – and faced them – were more likely to kill themselves.