9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

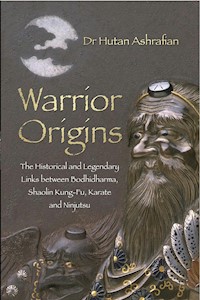

Warrior Origins is an account of the history and legends of the world's prominent martial arts and how they share a common heritage. It chronicles the origins of the Shaolin warrior monks, Shaolin Kung-Fu and their celebrated founder, Bodhidharma, who is also considered the first patriarch of Zen (Chan) Buddhism. The book considers Bodhidharma's origins in the context of ancient Persia and its royal houses and continues with the rise of Karate from ancient Okinawan roots to Japan and then into a global sport. It connects the record of Ninja and Ninjutsu and the influence of some of its latter luminaries, including Seiko Fujita, whilst also revealing new evidence on renowned martial artists such as Bruce Lee. This work takes a dramatically original approach to the heart of the martial arts and their founders. Author Dr Hutan Ashrafian, who holds black belt grades in several martial art styles, including a 5th Dan in Okinawan Goju-Ryu Karate and championship medals in Karate and Judo at World and European Masters level, delineates the inheritance of these arts using innovative evolutionary approaches to find previously unidentified links between them. Warrior Origins traces the pattern from Bodhidharma to the remarkable diversity of modern martial arts.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

The author training in the morning snow on London’s Primrose Hill, overlooking the city.

Cover Illustrations: Early nineteenth-century Japanese tsubas (sword hand guard), made of iron and decorated in high relief in silver, gold, shakudo (a gold/copper alloy also known as hakudo), copper and shibuichi (an alloy of three parts copper to one part silver). One piece (on the front and back) is credited to Egawa Toshimasa and depicts Sojobo, the King of the Tengu (a mythical semi-divine mountain spirit) clad in a mountain priest costume accompanied by one of his Tengu whilst teaching martial secrets using scrolls to the young warrior Minamoto no Yoshitsune – the legendary founder of Yoshitsune Ryu Ninjutsu. On the book spine is the Japanese Thunder God Raijin, or Raiden, with his tomoe (Japanese swirl) patterned drums, shooting down thunder and lightning. (This piece is decorated with patinated copper alloy, gold and copper inlay, credited to Kingyokudo Myochin Hirosada, 1857.) This character has inspired popular modern ‘thunder god’ personalities in contemporary martial arts computer games and gameplay media including ‘Lord Raiden’ in the Mortal Kombat series. Photos © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

No matter how you may excel in the art of te [‘art of thefist’ or Karate],

And in your scholastic endeavours,

Nothing is more important than your behaviour

And your humanity as observed in daily life.

Nago Ueekata Chobun(1663–1734), also known as Tei Junsoku. Okinawan scholar and government official.

Contents

Title

About the Author

Acknowledgements

Preface

1. Enter the Dharma

2. Shaolin and Kung-Fu

3. Unravelling the Silk Road

4. Prince of Persia

5. Power House (Zurkhane) and PPayattu

6. Karate

7. Ninja

8. Karate–Ninja Connections

9. Conclusion: Shaolin, Shorin, Shinobi

Appendix 1 The Death of Bruce Lee: A Medical Perspective

Appendix 2 Taekwondo

Notes

Copyright

About the Author

Hutan Ashrafian is a doctor, martial artist and historian. He has three decades of experience in Karate and has practised a wide range of traditional martial arts and sport combat systems. He has a particular interest in the evolution of Karate, Kung-Fu, Zurkhane and Ninjutsu. He has studied Chinese-Okinawan martial cross-fertilisation and practises several founding styles of Karate. He holds a 5th Dan Black Belt in the Okinawan Karate style of Goju-Ryu, Dan grades and instructorships in several other systems including Shito-Ryu, Seiki-kai and Shotokan. He has the Soke title (‘official inheritor’) in the Okinawan style of Gusuku-Ryu (‘Way of the Fortress’). He has successfully competed in both Karate and Judo, winning an array of gold, silver and bronze medals at World Junior, University, European and World Masters levels, and currently trains with the Jindokai International Martial Arts Association at the London School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) Dojo. Following qualification from medical school he was elected Fellow and council member of the Royal Asiatic Society and awarded membership of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. He completed a PhD in surgery and metabolic physiology and is currently a practising surgeon and clinical lecturer at Imperial College London.

The author, Hutan Ashrafian.

Acknowledgements

I dedicate this book with my deepest affection to my parents Jamshid and Susan and to my older brother Houman, with whom I began my journey in the martial arts, and also to our incredible first instructor Yoshihiro Itoshima, to whom we are eternally grateful for building the foundations of our Karate knowledge and practice.

Particular gratitude goes to Professor Stephen Chan OBE, 9th Dan Chief Instructor and President of the Jindokai International Martial Arts Association and a close friend, who has been guiding my martial journey from Westminster School and the international competition circuit through to the present day and onward. His exceptional abilities in the martial arts, world expertise on international relations, humanities and academia are a constant source of inspiration to me and countless others.

My yearning to understand the martial arts that I see and practise has been fed by training with dedicated, enthusiastic, like-minded individuals. As a result, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to the multitude of fellow martial artists (of all styles) I have had the pleasure of training alongside over the years; you have all been a massive inspiration.

The final stages of this book have coincided with my training at the Jindokai International Martial Arts Association at the London School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) Karate and Kobudo Dojo (located in the university ‘Dungeon’). I would therefore like to express deep appreciation to my Dojo mates: Dr Ranka Primorac, Peter Ayres, Katy Crofton, Dr Matthew O’Donnell and, of course, Dr Steve Taplin.

Special thanks to Gavin J. Poffley, my fellow Karate-ka and friend with whom I relish sparring competitively on the mats and discussing esoteric aspects of martial arts; I thank him for his expertise in Japanese, his ability to translate the most complex of texts and his help in proofreading this manuscript. I am also thankful to the wonderful Dr Leanne Harling for her translation of my vision of the cover, whilst also contributing to the proofreading.

I very much appreciate the recent international martial conferences conducted under the auspices of Col (Ret.) Roy Jerry Hobbs, 10th Dan Hanshi and Chief Instructor of the Dentokan Sekai Bugei Renmei, Inc., whose enormously broad martial expertise remains every motivating; the enlightening Brian Rogers and the inimitable Stuart Lawrence, who stayed open-minded to my crazy ‘fortress’ style of Karate whilst delighting in a heady mix of Okinawan, Chinese, Japanese and North American Goju styles! Thanks also go to Richard Thomas and Dr Alistair MacPherson from my time at Westminster School and Wayne Otto, the world Karate champion of champions and former England Karate coach for the magnificent competition sessions in London’s Crouch Hill, who have all been exposed to my hybridisation of history and martial arts and have contributed to my Dan grades and medals. I thank Sylvain Guintard (Revd Kuban Jakkôin), 8th Dan in ‘Ninpo’ Budo-Taijutsu, yambushi priest of Shomudo hermitage, for our discussions on the Yamabushi and all things Ninja.

I am indebted to Professor Richard N. Frye, with whom I have studied the ancient world from east to west for many years. His encyclopaedic knowledge of all things Persian and his effortless familiarity with the world of the orient have proved massively valuable.

My inquisitiveness about the martial arts has in part been derived from my career in medicine and science and thanks goes to my surgical colleagues and mentors, Professor Thanos Athanasiou and Professor Lord Ara Darzi.

This project would not have been possible without the significant knowledge freely shared by the multitude of martial artists with whom I have trained, and their open, welcoming culture that nourished fruitful discussion and was an inspiration to write this book.

Hutan Ashrafian

London

Preface

The martial arts are as old as as man. From the dawn of civilisation, we were able to advance ourselves beyond a condition of savage hand-to-hand aggression to a state of intelligent conflict resolution. Contests evolved from a haphazard demonstration of brute force to satisfy primal urges towards the higher goals of stability, protection and law enforcement. That is not to say that atrocities did not occur as they do today, but rather there was an increased appreciation of using force for good. A well-known example is that of Cyrus the Great of Persia, who invaded Babylon in 539 BCE in part to free all slaves, permit religious tolerance and to encourage international dialogue. Such a show of martial strength was based on the premise of what has been called the first ever bill of human rights, the Cyrus Cylinder c.539–530 BCE (a copy of which currently resides in the United Nations), and resulted in worldwide acknowledgement of the invader’s humanity at that time, which endures to the present day.

This show of martial strength was based on centuries of knowledge, even in Cyrus’ era, and in addition to the prerequisite strength of arms it was also based on strategy, skill and teamwork. These latter aspects of martial arts are now considered as accepted universal fundamentals, and they have been repeatedly refined into a multitude of schools, styles and systems.

Of the unarmed martial arts, there are currently four main systems or disciplines that fulfil the three criteria of (i) being practised by a large number of international students, (ii) having a traceable ancient history and (iii) having a worldwide impact. The so-called ‘foundation schools’ are Kung-Fu, Karate, Taekwondo and Ninjutsu. Kung-Fu is also known as Shaolin or Wushu Kung-Fu/Gung-Fu (or Gongfu, a Cantonese word meaning ‘effort’ or ‘perseverance’ that only took on the meaning of ‘Chinese unarmed martial arts’ quite recently; another common term is ‘Chuan Fa’). These schools of course overlap and vary tremendously, such that Kung-Fu represents an umbrella term to cover myriad Chinese schools representing the huge Chinese populace, whereas Ninjutsu is not practised by large populations, but nevertheless has penetrated modern culture and society to an extraordinary degree. Dedicated training in any of these arts leads to an age-old set of questions: how did each particular school commence? Where and when did it occur and why? The goal of this book is to investigate and clarify the legendary and historical origins of these martial arts, paying particular attention to occasions when their records coincide and agree.

Certain concepts regarding the history and development of the martial arts are increasingly becoming accepted and each style’s origin is being scrutinised much more closely than before. Simply reading books such as Sun Tzu’s Art of War or the Hagakure is no longer enough; now there is a desire to know why these books were written, in what context, and by whom. This book is not intended to be a reference work describing every legend and record of each martial arts style and substyle, but has been written to equip the reader with facts and concepts that can be applied over a wide field; and if a practitioner, to the interpretation of his or her own art, whatever that may be. It contains a number of key descriptions of pertinent schools, techniques and individuals intended to communicate to the reader relatively complex temporal associations in martial arts evolution. I have kept these as accurate as possible, but have purposefully aimed to keep my descriptions succinct so as to not to render them overly intricate.

This book is not intended as a practical manual of fighting arts; such ‘training manuals’ already exist in large numbers (and will necessarily differ greatly in training techniques, as this text will hopefully clarify).

The aim is to elucidate and integrate knowledge regarding the mainstream martial arts and consider possible connections and common origins, a subject discussed in nearly every martial arts club or dojo, but one that always seems to need deeper understanding. At a practical level, the comprehension of many of the advanced forms in Karate, Ninjutsu and Kung-Fu would be incomplete without knowing their original interpretation. At an epistemological level therefore, we need to comprehend the origins of our martial knowledge and skills. The book aims to equip the reader with the knowledge of how each particular school commenced, when, and why.

In the vast majority of cases, the historical record of these arts is incomplete, particularly the farther we go back in time. As a result, many martial artists have to view their historical provenance through the intermingling of some history with a wider influx of legends. The use of these legends of course lends itself to almost effortless dissemination in dojos and training halls, as they follow a straightforward oral tradition. Consequently, much of our comprehension of the development of martial arts is based on conjecture. I have written this book to offer the reader a framework within which to consider the development of modern martial arts, and am aware that there will always be new facts (and even more legends) to replace or add to the current record. I also make use of several biological analogies that convey concepts of martial art evolution. I have made comparisons using Darwinian and neo-Darwinian concepts to portray ideas and thoughts. To this end, I have reflected the application of evolutionary biology in the title of this book as a respectful tribute to Charles Darwin’s seminal treatise On the Origin of Species. I have aimed to bring new insight into the evolution of martial arts using existing legends and history through the creation of martial arts evolutionary trees.

Transliteration:

The transliteration within this book has been a particularly interesting consideration. Sources include Middle Persian, Farsi, Sanskrit, Japanese, Korean and both Cantonese and Mandarin. I have attempted to keep to accepted philological standards where possible, but have on occasion deviated to the popular interpretation of terms where appropriate. Any inconsistencies herein are in all cases my fault rather than errors by those who advised me on the manuscript.

1

Enter the Dharma

The enigmatic origins of the martial arts are a preoccupation of martial artists worldwide. Attending the training halls of the most prominent and popular styles from around the globe including Kung-Fu, Tai Chi, Karate and Taekwondo, you will hear an almost universal claim that these schools have a lineage that can be traced back to a monk known best in the English-speaking world by his Indian name: Bodhidharma (Damo in Chinese, Daruma Taishi in Japanese). The fact that this monk is also considered to be the father, or first patriarch, of Zen (Chan) Buddhism adds to these origins stories a feeling of legitimacy; and also assumes for the fighting arts a spirituality, in the association with Zen philosophy and ascetic practices.

Instructors of all levels and grades proudly list their personal lineage of training, reverentially putting pictures of their particular style’s forefathers on the wall and almost always acknowledging that Bodhidharma was the first of all. The monk is also depicted proudly alongside the more recent forefathers, with a short explanation that he had ‘created’ the first martial art of Shaolin Kung-Fu, which eventually evolved into many different schools and other martial arts, such as Karate. Many Japanese dojos to this day are inaugurated by the painting of eyes on Bodhidharma dolls, whose subsequent auspicious open-eyed presence will favour the martial enlightenment of their students. (In Japan this is actually a widespread practice outside of the martial arts too, especially for shop openings and during election campaigns.)

The ‘creation story’ of the martial arts in many clubs is typically recounted thus. Bodhidharma was travelling from India to China, when he encountered a group of weakened and sickly monks at the Shaolin Ssu (Young Forest Temple), the site where the practices known as Shaolin Boxing, Wushu or Kung-Fu would later originate. As a result, he designed and instigated a series of health-giving exercises in the monks’ daily routines (some based on the movements of animals). The monks then flourished physically, and continually practised these exercises, which eventually became known as Kung-Fu. As most of the Asian martial arts claim descent from this style of fighting, Bodhidharma is largely credited as ‘the father of all martial arts’. Zen Buddhist schools often use the same story but usually ask the first Zen question, why did Bodhidharma travel to the East?

In view of the current popularity of martial arts, it is no overstatement to say that billions of people worldwide readily consider Bodhidharma as the originator of their martial art, sport, or even Buddhist religion. However, the direct evidence to support these claims is not clear. There are of course a wide variety of legends ascribed to Bodhidharma, no doubt having been told, retold and modified for hundreds, if not thousands of years. Travelling to various clubs around the world, both in the East and West, provides the practitioner with interesting insights about the evolution of these legends, as they form a patchwork of narratives regarding this monk’s life. There is currently a significant lack of firm historical details regarding Bodhidharma, and any true morsels of evidence are overwhelmed by the surfeit of legendary stories to such an extent that discriminating between history and legend is like untying the Gordian knot. Is it possible to dissect out the real history from the fiction? Unsurprisingly, varying groups of martial artists and historians are polarised regarding Bodhidharma; some unquestioningly pronounce their faith in the truth of his legendary exploits whilst others question whether he even existed. Is there any tangible evidence of his existence, or his origins and his deeds? What was his contribution to the founding, establishment and development of the martial arts and what has his impact been to this day?

By the fifth century CE of the Julian calendar, the world as we know it was beginning to take shape, with the foundations of institutions, philosophies and cultures that we would readily recognise today. In Western Europe, the Roman Empire was gradually declining and the Anglo-Saxons were settling in Britain. Technological and social sophistication and refinement were international phenomena that were being constantly and independently reinvented, so that in the Americas, for example, the Maya were building massive stone temples comparable to those of the ancient Egyptians, although with completely different technology.

The East was no different and China had its Southern and Northern dynasties, whilst in Persia the empire of the Sassanids was comfortably established. The famed Silk Road between them that allowed the mutually beneficial transmission of goods and culture had already been in existence for many centuries and with the political and military strength of these territories, communication and exchange was flourishing. In India, a ‘golden age’ was taking place, and both religion and science were thriving (the concept of the number zero having been invented during this time).

In these times of cultural development and transmission of ideas, religion was taking a prominent role. The Persians were adhering to their ancient religion of Zoroastrianism, considered by many as the world’s oldest monotheistic belief system, whilst St Augustine of Hippo, who had himself studied Zoroastrianism and its Gnostic-type offshoot of Manichaeism, had written the important Christian work: The City of God (De Civitate Dei). Hinduism, which had existed for several millennia, was constantly expanding, and the newer religion of Buddhism had commenced a late but continual expansion, particularly through its Mahayana school.

It is through Mahayana Buddhism that we first come across the name of Bodhidharma. Although historically this religious sage is understood to have studied the Mahayana way, he is largely famed for and credited with founding the Zen (Chinese: Chan) strand of Buddhism, and instigating the exercises and forms that he subsequently taught to monks at Shaolin.

Opinions are split as to the importance of these proto-martial exercises as although the legends of Bodhidharma allude to the fact that he introduced and created the basic forms of the martial arts, he is also reputed to have achieved his spiritual self-enlightenment not through their practice but through contemplation and meditating for years on end. This gives credence to those Zen Buddhists who believe in a more formal and conservative practice of meditation without the incorporation of martial arts or strenuous exercise. Furthermore, the Zen (Chan) Buddhism of the famed Shaolin monks is more akin to some sects of Buddhism in Tibet, Korea and the smaller schools of Japan than it is to Chinese and mainstream Japanese schools of martial arts and Buddhism. The Shaolin School can be seen to have Taoist influences, and uses a large amount of martial practice to augment and accompany meditation. The martial arts are used to strengthen the body, allowing deep meditation to occur. Other schools of Zen believe in more of a deep and continued static meditation, allowing the mind to empty.

The fact that both martial artists and Zen Buddhists independently claim their philosophy as coming from the same Bodhidharma lends some credence at least to the idea that one or a group of monks started their school at approximately the same time and place in northern China. Indeed, with the many years of rewriting history, and political propaganda, one could easily imagine that martial artists and Zen Buddhists could have come up with different and independent originators of their disciplines, which later became confused and unified into the same individual. But the fact that both strongly adhere to the one unified Bodhidharma theory reinforces the implication that it was indeed one of the same group of monks, bearing the name Bodhidharma, who founded both disciplines.

Variations of the name Bodhidharma are listed in various Asian languages as:

Sanskrit:

Bodhidharma or Bodhi Dharma

Chinese – Cantonese:

Pou Dai Daat Mor or Daat Mor

Chinese – Mandarin (Pinyin):

Pu Ti Da Mo or Da Mo

Japanese:

Daruma or Daruma Taishi

Vietnamese:

Bo de dat ma

Korean:

Dalma or Boridalma

This name is accepted by many as not being his birth name but an adopted name when he entered the Buddhist order, probably given to him by his master or seniors, as in Sanskrit it means ‘he who has reached enlightenment’.

As mentioned previously, there is no lack of conflict regarding the authenticity of the legends of Bodhidharma, a not uncommon finding when dealing with the posthumous chronicles of influential figures. However, it is important to note that there is an almost complete unity in the belief of the single figure of Bodhidharma as the first forefather, even though the context can be subject to speculation. The fact that he started what we know today as the Asian martial arts and first passed it on to the Shaolin monks is generally accepted in folklore. However, some claim that although he was the first Patriarch of Zen Buddhism in China, he was not the first patriarch or originator of this strand of Buddhism in India, and indeed posit that he learned and adopted Zen as a disciple from one of the Indian patriarchs before taking it to China. Others say that Zen existed in China before Bodhidharma and that he came later, and was simply effective at promoting, teaching and disseminating this new form of spirituality. The orthodox view, however, is clear: Bodhidharma was the originator of Zen Buddhism and the first Zen Buddhist patriarch in the world.

2

Shaolin and Kung-Fu

As it is practically impossible to date the origins of the various legends attributed to Bodhidharma himself, they are reported here in a loose chronological order of the monk’s life. Actual historical evidence is scrutinised in Chapter 3.

We are told virtually nothing about Bodhidharma’s childhood and he is generally described as appearing on the stage of history as a middle-aged or even as an elderly man (Figure 1). He is reputed to have had piercing blue eyes and very dark black hair. His hair was copious, especially on his chest, seen coming out of his monk’s robes, which made him notable in China as the presence of such hair made him stand out when compared to the comparatively bare-chested Chinese men.

He is shown sometimes wearing an earring and is portrayed as having a very prominent nose, which together with his blue eyes added to his reputation as an outsider or alien. Blue eyes are another rare trait in the ethnic Chinese (and also in the indigenous peoples of neighbouring India and Persia) and his eyes became an important subsequent characterising feature in artistic representations, where they are usually illustrated as bulging out. This effect adds to the aura he is attributed with in the chronicles, as having the almost superhuman ability to attain a profound meditative state with a steely and unremitting stare.

Most legends state that Bodhidharma came from south-east India and was born c.440–470 CE on 5 October (Chinese lunar calendar). Another date given is 482 CE. He is described as the third son of a ‘great king’. More specifically, this is thought to be King Sugandha from a dynasty known as the ‘Sardilli’, or, according to the theory favoured by most narratives and South Indologists, the Pallava King Simhavarman (ruling between 436–460 CE) who was based in the region of Tamil Nadu in the ancient city of Kanchi or Kanjeevaram (today’s Kanchipuram). This is significant, as at one point in history Kanjeevaram was a Buddhist kingdom. Some legends give Bodhidharma’s birth name as ‘Bodhitara’ or ‘Bodhipatra’.

Some claim that he was born into the priestly caste (Brahmanas), whilst others describe him as originating in the warrior caste (Kashatriyas). The stories that adopt the latter go on to state that he learned armed and unarmed combat such as Kalarippayattu, Vajra Mushti, Kuttu Varisai or any of the indigenous martial arts likely to have come from what were then known as the Dravidian combat schools.

Those who believe in his Brahminic origins say that he trained in various schools of Yoga (Devanagari), specifically the four branches of yoga explained in the Sanskrit text Bhagavad Gita (Song of the Lord, c.400–100 BCE). These are Karma yoga (action and exercise), Jnana yoga (knowledge), Bhakti yoga (religious devotion) and Raja yoga (meditation).

Figure 1: Image of Bodhidharma in the cave.

As he was the third son, this allowed him the freedom to adopt a religious life, as the first royal son typically would be responsible for the family lands and inheritance of leadership, whilst the second would be expected to devote himself to the military and matters of national defence. Although this is a tenable theory, such a practice was never strictly adhered to and would be highly variable. A good example would be the case of Siddhartha Gautama, the founding Buddha, who was the first son of a king but adopted the religious life, leading to his founding of Buddhism. Furthermore, there would have been no onus on a young Bodhidharma to specifically adopt Buddhism, with Hinduism or one of ancient India’s many other religions being a more likely choice. Whatever his status at birth or origins, Bodhidharma somehow experienced and later converted to Buddhism, allegedly after his father’s death, giving up worldly belongings in favour of a more simple monastic life.

His master, the sage Prajnatara (also known as Prajnadhara or Panyata) was the twenty-seventh patriarch of Indian Buddhism, apparently in a direct line of descent from the Buddha himself. A Mahayanist, he is reputed to have come from Magadha in the ancient Indo-Aryan kingdom of Mahajanapadas, one of the four main kingdoms of ancient India. Siddhartha Gautama himself travelled southward to Magadha during his journeys before becoming the Buddha, and in 326 BC Alexander the Great’s army reputedly mutinied at the thought of fighting at Magadha, therefore forcing Alexander to turn south and ultimately return homeward via Persia.

Bodhidharma, being an astute and gifted student, rapidly progressed in his Buddhist schooling and in time was acknowledged as an ‘enlightened master’, becoming the twenty-eighth Patriarch of Indian Buddhism. Some Zen legends differ, stating that at the flower sermon on Vulture Peak the Buddha did not speak and just silently held up a flower. He saw that only an individual disciple, a monk named Kasyapa, was smiling and that it was he alone who had understood the teaching that day. This event is accepted as the first ‘transmission of the lamp’, a direct communication of mind without words, with Kasyapa receiving the Dharma directly at that time and the Buddha renaming him Mahakashyapa to commemorate it. According to some Zen schools, this therefore makes Mahakashyapa the first Zen patriarch, and Bodhidharma the twenty-eighth.

Prajnatara asked Bodhidharma to travel to China, as he believed Buddhism had begun to perish there, and he wanted Bodhidharma to further develop Mahayana there, maybe establish Sarvastivada teachings or even introduce Zen to that continent. Alternatively, others say that Buddhism was declining in India and that Prajnatara asked Bodhidharma to transmit Buddhism to China to ensure the continuation of their school of Buddhism. His journey was difficult, the elements were harsh and he endured various difficulties with thieves and robbers. Some Chinese legends inform us that he commenced his journey in 470 CE aged 117 years, bringing with him books on martial arts.

There are a variety of routes suggested for the journey. Most legends allude to Bodhidharma walking via the Silk Route or, alternatively, through Tibet and the Himalayas. Other legends have a sea route, via the Bay of Bengal, sailing to Guangzhou (Canton), and from there to the capital, Jiankang (an ancient name for Nanjing). He was said to be 120 years old at that time, the journey having taken approximately three years, with an estimated date of arrival of 473–527 CE, most accounts alluding to 520 CE.

Once in China, Bodhidharma meets a local military administrator named Shang Yao (or Shao Yang), who informs the ruling monarch of the time of his presence. This was Emperor Wu of Liang (also known as Liang Wudi, 464–549) of the South dynasty, who subsequently asked Bodhidharma for a royal audience (he reigned 502–549). The emperor was well read and a devout Buddhist, and was keen to meet distinguished foreign Buddhist monks in order to discuss religion and to display his charitable contribution to many Buddhist works, monks and temples. He had commissioned the translation of many sutras from Sanskrit to Chinese, all in reverence of the Buddha. He would have been keen to learn new Buddhist concepts and reinforce his beliefs, maybe even getting the monk to strengthen his Buddhist and royal authority, or help him set up more monasteries and temples.

The emperor, believing in karma (good begets good and bad begets bad), is famed for having asked the monk what merit he had earned for erecting numerous Buddhist temples and completing various charitable deeds in the name of the Buddha. Bodhidharma replied that he had earned nothing at all, going on to explain that superficial and worldly deeds are not the path to enlightenment, and implying that the emperor’s deeds had not been altruistic but rather self-adulating, negating any karmic benefits.

A second question was posed: what is the fundamental concept of Buddhism? To which Bodhidharma famously replied, ‘vast emptiness’. A final question was posed: who did the monk think he was? This insinuated that he had not realised the high social standing and authority of his host. The final answer by the monk continued in its simplicity: he had no idea of who he was.

The two characters parted company in a civilised but frosty fashion, although some do say that the emperor actually had Bodhidharma banished from his kingdom. There is, however, no story of any compulsion or violence being used.

After leaving the palace and city of Nanjing, Bodhidharma headed north, some say with the aim of visiting Lo-yang, a capital of ancient North China. In doing so, he had to cross the mighty Yangtze River. The local community did not want the monk to leave them or to cross the river, so they set all their boats adrift to prevent his passage. He famously overcame this impasse by using a single reed, throwing it on the water, then stepping onto it whilst in a state of meditation. By doing so, he himself acted as a sailboat, and let the river breeze transfer him across to the other side.