7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

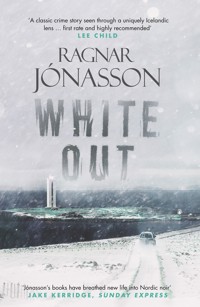

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Dark Iceland

- Sprache: Englisch

THE FOURTH INSTALMENT IN THE INTERNATIONAL BESTSELLING DARK ICELAND SERIES OVER A MILLION COPIES SOLD When the body of a young woman is found dead beneath the cliffs of the deserted Icelandic village of Kálfshamarvík, police officer Ari Thór Arason uncovers a startling and terrifying connection to an earlier series of deaths, as the killer remains on the loose… 'Jónasson's books have breathed new life into Nordic noir' Sunday Express 'Jónasson skilfully alternates points of view and shifts of time … The action builds to a shattering climax' Publishers Weekly ________________ Two days before Christmas, a young woman is found dead beneath the cliffs of the deserted village of Kálfshamarvík. Did she jump, or did something more sinister take place beneath the lighthouse and the abandoned old house on the remote rocky outcrop? With winter closing in and the snow falling relentlessly, Ari Thór Arason discovers that the victim's mother and young sister also lost their lives in this same spot, twenty-five years earlier. As the dark history and its secrets of the village are unveiled, and the death toll begins to rise, the Siglufjordur detectives must race against the clock to find the killer, before another tragedy takes place. Dark, chilling and complex, Whiteout is a haunting, atmospheric and stunningly plotted thriller from one of Iceland's bestselling crime writers. ________________ 'Traditional and beautifully finessed …morally more equivocal than most traditional whodunnits, and it offers alluring glimpses of darker, and infinitely more threatening horizons' Andrew Taylor, Independent 'Jónasson has come up with a bleak plot and characters, but his evocation of Iceland's chilly landscape is hard to put down' Sunday Times 'A distinctive blend of Nordic Noir and Golden Age detective fiction … masterful' Laura Wilson, Guardian 'Required reading' New York Post 'Puts a lively, sophisticated spin on the Agatha Christie model, taking it down intriguing dark alleys' Kirkus Reviews 'The best sort of gloomy storytelling' Chicago Tribune 'The prose is stark and minimal, the mood dank and frost-tipped. It's also bleakly brilliant, although perhaps best read with a warming shot of whisky by your side' Metro 'A classic crime story seen through a uniquely Icelandic lens … first rate and highly recommended' Lee Child 'Ragnar Jónasson writes with a chilling, poetic beauty - a must-read' Peter James 'A modern take on an Agatha Christie-style mystery, as twisty as any slalom' Ian Rankin 'Seductive … Ragnar does claustrophobia beautifully' Ann Cleeves

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 339

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR RAGNAR JÓNASSON

‘I enjoyed Ragnar Jónasson’s Snowblind – a modern Icelandic take on an Agatha Christie-style mystery, as twisty as any slalom…’ Ian Rankin

‘A classic crime story seen through a uniquely Icelandic lens … first rate and highly recommended’ Lee Child

‘Jónasson skillfully alternates points of view and shifts of time … The action builds to a shattering climax’ Publishers Weekly

‘A tense and convincing thriller; Jónasson is a welcome addition to the roster of Scandi authors…’ Susan Moody

‘…a chiller of a thriller … It’s good enough to share shelf space with the works of Yrsa Sigurðardóttir and Arnaldur Indriðason, Iceland’s crime novel royalty’ Washington Post

‘Required reading’ New York Post

‘Puts a lively, sophisticated spin on the Agatha Christie model, taking it down intriguing dark alleys’ Kirkus Reviews

‘Economical and evocative prose, as well as some masterful prestidigitation’ Guardian

‘The best sort of gloomy storytelling’ Chicago Tribune

‘Ragnar Jónasson writes with a chilling, poetic beauty – a mustread addition to the growing canon of Iceland Noir’ Peter James

‘British aficionados of Nordic Noir are familiar with two excellent Icelandic writers, Arnaldur Indriðason and Yrsa Sigurðardóttir. Here’s a third: Ragnar Jónasson … the darkness and cold are palpable’ The Times

‘A truly chilling debut, perfect for fans of Karin Fossum and Henning Mankell’ Eva Dolan

‘A challenging investigation that uncovers local secrets … Scandi Noir meets old-fashioned murder mystery in an atmospheric whodunnit’ Daily Express

‘Seductive … an old-fashioned murder mystery with a strong central character and the fascinating background of a small Icelandic town cut off by snow. Ragnar does claustrophobia beautifully’ Ann Cleeves

‘His first novel to be translated into English has all the skillful plotting of an old-fashioned whodunnit although it feels bitingly contemporary in setting and tone’ Sunday Express

‘On the face of it, Snowblind is a gigantic locked-room mystery, an investigation into murder and other crimes within a closed society with a limited number of suspects … Jónasson plays fair with the reader – his clues are traditional and beautifully finessed – and he keeps you turning the pages. Snowblind is morally more equivocal than most traditional whodunnits, and it offers alluring glimpses of darker, and infinitely more threatening horizons’ Independent

‘Ragnar Jónasson’s Snowblind is as dazzling a novel as its title implies and the wonderful Ari Thór is a welcome addition to the pantheon of Scandinavian detectives. I can’t wait until the sequel!’ William Ryan

‘Whiteout is all kinds of brilliant. Great characters, a gripping plot and a hauntingly atmospheric location. Another book added to my all-time favourites list’ Bibliophile Book Club

‘An isolated community, subtle clueing, clever misdirection and more than a few surprises combine to give a modern-day golden-age whodunnit. Well Done! I look forward to the next in the series’ Dr John Curran

‘This is almost a classic Scandinavian Noir setup, but Ragnar Jónasson is full of surprises … I loved it’ Mystery Scene Magazine

‘…brings you the chill of a snowbound Icelandic fishing village cut off from the outside world, and the warmth of a really well-crafted and translated murder mystery’ Michael Ridpath

‘Jónasson has taken the locked-room mystery and transformed it into a dark tale of isolation and intrigue that will keep readers guessing until the final page’ Library Journal

‘Jónasson spins an involving tale of small-town police work that vividly captures the snowy setting that so affects the rookie cop. Iceland Noir at its moodiest’ Booklist

‘A fantastic golden-age mystery novel with hard-hitting themes and a flawless writing style which lulled me into a false sense of security…’ Chillers, Thrillers and Killers

‘Elegantly and cleverly paced, with a plot that grips and a totally unexpected ending, this is crime writing of the highest quality’ Random Things Through My Letterbox

‘Beautifully evocative of place and character, these books are a pure delight to read’ Louise Wykes

‘Brilliantly atmospheric and claustrophobic’ Have Books Will Read

‘Crime fiction at its most exciting and storytelling at its most authentic … The Dark Iceland series is fast becoming a book shelf collection classic’ The Word’s Shortlist

‘The complex characters and absorbing plot make Snowblind memorable. Its setting – Siglufjördur, a small fishing village isolated in the depths of an Icelandic winter – makes it unforgettable. Let’s hope that more of this Icelandic author’s work will be translated’ Sandra Balzo

‘In Ari Thór Arason, Nordic Noir has a new hero as compelling and interesting as the Northern Icelandic setting’ Nick Quantrill

‘If a golden-age crime novel was to emerge from a literary deep freeze then you’d hope it would read like this. Jónasson cleverly squeezes this small, isolated town in northern Iceland until it is hard to breathe, ensuring the setting is as claustrophobic as any locked room. If you call your book Snowblind then you better make sure it’s chilling. He does.’ Craig Robertson

‘A clever, complex and haunting thriller … moves inexorably to a conclusion that is both unexpected and gripping’ Lancashire Post

‘If Arnaldur is the King and Yrsa the Queen of Icelandic crime fiction, then Ragnar is surely the Crown Prince … more please!’ Karen Meek, EuroCrime

‘Ragnar Jónasson brilliantly evokes the claustrophobia of smalltown Iceland in this intriguing murder mystery. Let’s hope this is the first of many translations by Quentin Bates’ Zoë Sharp

‘Ragnar Jónasson is simply brilliant at planting a hook and using the magic of a dark Icelandic winter to reel in the story. Snowblind screams isolation and darkness in an exploration of the basic Icelandic nature with all its attendant contrasts and extremes, amid a plot filled with twists, turns, and one surprise after another’ Jeffrey Siger

‘Another superb read and a fine example of the way in which Jónasson uses atmosphere to create the ultimate sense of dread while not sacrificing the integrity and authenticity of the setting’ Jen Med’s Book Reviews

‘The whole series is a chilling delight to read’ Never Imitate

‘…An Agatha Christie-like quality, but darker and more sinister. Whiteout takes a possible “cosy” murder and a group of plausible suspects, interrogates them, throws in some false clues, mixes well, and sees who comes out as the guilty party … clever’ TripFiction

‘Jonasson’s writing style is very purposeful and totally unmatched by anyone else. Every single word has a meaning deeper than its literal definition, yet there is a simplicity and a quiet gentleness about it … absolutely perfect’ Novel Gossip

‘Tense, thrilling and at times quite dark, Rupture delivers a GARGANTUAN five-star read!’ Ronnie Turner

‘With the lightest of descriptive touches and a melancholy colour scheme, Ragnar Jónasson leaves us with some open questions about the nature of justice and the power of redemption’ Crime Fiction Lover

‘A chilling, thrilling slice of Icelandic Noir’ Thomas Enger

‘A stunning murder mystery set in the northernmost town in Iceland, written by one of the country’s finest crime writers. Ragnar has Nordic Noir down pat – a remote small-town mystery that is sure to please crime fiction aficionados’ Yrsa Sigurðardóttir

‘Snowblind is a brilliantly crafted crime story that gradually unravels old secrets in a small Icelandic town … an excellent debut from a talented Icelandic author. I can’t wait to read more’ Sarah Ward

‘Is King Arnaldur Indriðason looking to his laurels? There is a young pretender beavering away, his eye on the crown: Ragnar Jónasson…’ Barry Forshaw

‘Ragnar Jónasson has delivered an intelligent whodunnit that updates, stretches, and redefines the locked-room mystery format. The author’s cool clean prose constructs atmospheric word pictures that recreate the harshness of an Icelandic winter in the reader’s mind. Destined to be an instant classic’ EuroDrama

‘A beautifully written thriller, as tense as it is terrifying – Jónasson is a writer with a big future’ Luca Veste

‘It sometimes feels as if everyone in Iceland is writing crime novels but the first appearance of Ragnar Jónasson in English translation (itself a fluid adaptation by British mystery writer Quentin Bates) is cause for celebration’ Maxim Jakubowski

‘Snowblind has given rise to one of the biggest buzzes in the crime fiction world, and refreshingly usurps the cast iron grip of the present obsession with domestic noir … a complex and perplexing case, in a claustrophobic and chilling setting…’ Raven Crime Reads

‘The intricate plotting is reminiscent of the great Christie but the setting is much more modern and darker. There is an increasing tension and threat that mirrors the developing snow storm and creates a sense of isolation and confinement, ensuring that the story develops strongly once the characters and scene are laid out’ Live Many Lives

‘A brooding, atmospheric book; with the darkness and constant snow there is a claustrophobic feel to everything’ Reading Writes & For Reading Addicts

‘It is surely only a matter of time before Snowblind and the rest of Ragnar’s Dark Iceland series go on to take the Nordic Noir genre by storm. The rest of the world has been patiently waiting for a new author to emerge from Iceland and join the ranks of Indriðason and Sigurðardóttir and it appears that he is now here’ Grant Nicol

‘Jónasson’s prose throughout this entire novel is captivating, and frequently borders on the poetic, constructing something that is both beautiful and uncomfortable for the reader’ MadHatter Reviews

‘A subtle, quiet mystery set in the most exquisite landscape – a slow burner that will suck you in and not let you go’ Reading Room with a View

Whiteout

RAGNAR JÓNASSON

translated by Quentin Bates

For my brother, Tómas.

‘Come into my flower garden, black night! I’ll not miss your dewfall, now that all my flowers are dead…’

from Haust, Jóhann Jónsson (1896–1932)

Contents

Pronunciation guide

Icelandic has a couple of letters that don’t exist in other European languages and which are not always easy to replicate. The letter ð is generally replaced with a d in English, as in Gudmundur, Gudfinna, Hédinn and place names ending in -fjördur. In fact, its sound is closer to the hard th in English, as found in thus and bathe.

Icelandic’s letter þ reproduced as th, as in Ari Thór, is equivalent to a soft th in English, as in thing or thump.

The letter r is generally rolled hard with the tongue against the roof of the mouth, and Icelandic words are pronounced with the emphasis on the first syllable.

PROLOGUE

The little girl stretched out her hands, and then everything happened so quickly that she had no chance to cry. Gravity took over and she simply fell.

The sea and the rocks were there right in front of her.

She was too young to recognise death as it approached.

The point, the beach, the lighthouse, the wonderland around her – all these had been her very own playground.

And then she hit the boulders below.

PART ONE

PRELUDE TO A DEATH

I

It was a sight Ásta Káradóttir would never forget, even though she had only been a child when she saw it – or maybe for that very reason.

She had been in her room in the attic when it happened. The door had been shut, as had the windows, and the air in the room was stale. She had been sitting on the old bed that would creak beneath her when she turned over in the night, staring out of the window. Maybe, or even probably, there were things that subsequently seeped into her recollection of that day, drawn from other childhood memories. But what she saw – the terrible event she witnessed – would never leave her.

She had never told a soul about it.

And now she had returned after a long exile.

It was December and the light snow – just a thin layer that covered everything – was a reminder that Christmas was almost here. There had been a drizzle of rain when she had driven up from the south, and the weather had been relatively warm. With the heater running to keep the windscreen clear, the car had become almost unbearably hot.

Ásta had found her way out of central Reykjavík without a hitch – driving up Ártúnsbrekka and leaving the city where life was like bad sex: better than nothing, but only just. Not that she was expecting to leave her life behind her completely. Her intention was to bid adieu to the monotonous reality – the dingy basement flat and the sixty-eight square metres of claustrophobia and darkness. Sometimes, to alleviate the gloom, she would draw back the curtains, but that just meant that the passers-by on her busy street could peek in through the windows, spy on her comings and goings, and look down on her, as if she had given up on any claim to privacy by living in a basement and not drawing the curtains.

Then there were the guys she brought home sometimes at the weekend, when she was in the mood. Some of them wanted to keep the lights on and the curtains open – to make love in plain sight.

She was still young, only a few years past thirty, and while she was very aware she was not past the flush of youth, she was tired of the endless humdrum routine of temporary work and night shifts; fed up with scratching a living on benefits or minimum wage and living in a rented apartment in the centre of town.

To reach her destination, she had driven through the western part of Iceland and over the high mountain pass that led to the north, all the way up to the Skagi peninsula, to Kálfshamarsvík. She had never meant to come back, but here she was, carrying those old secrets with her. She had spent the day travelling, so when she arrived the bay was deep in evening darkness. She stood for a while and looked at the house. It was a fine building with two main floors, an attic and a basement. The architectural style probably pre-dated the house itself, even though it had been there for decades. It was painted a smart, clean white, with a dark-grey exposed foundation, and had curved balconies on the upper floor. Ásta and her sister had lived in the attic with their father and mother for a while. No expense had been spared when the house had been built.

There was a light on downstairs, where she recalled that the living room had been, and a lamp illuminated the front door. These two were the only lights, apart from the glow from the lighthouse on the point, of course. There was an undefinable grace to the interplay between light and shadow; the lights were unnaturally bright in the darkness. This was an area of great natural beauty and rich history, with remnants of disappeared houses hidden everywhere.

With no reason to hurry Ásta set off towards the house slowly, drinking in the fresh night air, and stopping occasionally to look at the sky and let the falling flakes of snow tickle her face.

She hesitated at the front door before knocking.

Was this really a good idea?

A sharp gust of wind sent a chill down her back, and she looked around quickly. The loud mutter of the wind had given her a sudden feeling of disquiet; it was as if someone was standing behind her.

Ásta looked around her, simply to convince herself that this wasn’t the case.

The darkness greeted her. She was alone, the only footprints in the white snow were her own.

It was too late to turn back.

II

‘He wouldn’t have wanted you to stay here,’ Thóra said, more to herself than to Ásta. This was the second, maybe the third time that she had said the same thing, in one form or another.

Thóra was well into her sixties but she hadn’t changed much in the past twenty-five years. She had the same neutral expression, the same distant eyes and the same irritating, nagging voice.

Óskar, Thóra’s elderly brother, sat at the piano at the far end of the living room and played the same quiet theme over and again. He had never been one for talking – was always quick to finish his coffee and make his way back to the piano.

Thóra seemed to be doing her best to make Ásta welcome. They had tried to reminisce about the old days, but the difference in their ages was too much for them to have many shared memories. The last time they had met, Ásta had been seven years old and Thóra around forty. What they did have in common, though, was that they both remembered Ásta’s father, so naturally, part of the conversation was about him.

‘He wouldn’t have wanted it,’ Thóra repeated.

Ásta nodded and smiled politely. ‘It’s not worth discussing,’ she said finally. ‘He’s dead and Reynir offered me a place to stay.’ She didn’t mention that it wasn’t Reynir who had broached the idea; rather that she had called him and asked if she could come for a few days.

‘Well, that’s the way it is,’ Thóra replied.

Óskar continued to play the same theme, not badly, but competently enough, filling up the awkward gaps in the conversation.

‘Does Reynir live here all year round?’ Ásta asked, although she was sure of the answer. As the sole heir of a wealthy businessman, Reynir Ákason had been in the media spotlight for years. Ásta had read a few interviews with him in which he said that, when he was in Iceland, the only place he wanted to be was out in the countryside.

‘More or less,’ Thóra replied. ‘That might change now that his old man is no longer with us. I expect you saw it in the papers a fortnight or so ago – that he passed away.’ She dropped her voice in apparent respect for the deceased, but her tone sounded affected. ‘Óskar and I were going to travel south for the funeral, but Reynir said there was no need for that. Reykjavík cathedral is such a small church anyway. And we didn’t know him well – he wasn’t here that much. As father and son they weren’t much alike.’ She paused before continuing. ‘It must be a lot of work for Reynir taking over all that business, all those investments. I don’t know how he manages it. But he’s a smart one, that boy.’

That boy, Ásta thought. He couldn’t have been much over twenty the last time they had met. Of course, back then he had been a grown man in the eyes of a girl of seven. Smart, yes, with an air of experience and ambition about him. He had been an enthusiastic yachtsman, clearly entranced by the sea, just as Ásta had.

‘That boy,’ she said aloud. ‘How old is he now?’

‘Getting on for fifty, I’d say. Not that he’d admit it.’ Thóra tried to smile, but it was a half-hearted effort.

‘He still lives in the basement?’

The offhand question swept like a cold blast of air through the room. Thóra stiffened and stayed silent for a long moment. Thankfully, as before, Óskar continued to play. Ásta glanced at him. Hunched over the piano keyboard, he had his back to them. Everything about his bearing was tired. He wore brown cord trousers and the same dark-blue rollneck sweater as he had worn in the old days; or maybe it was a close relative who’d worn those clothes.

‘Óskar and I have moved in there,’ Thóra said, her reply failing to sound as nonchalant as she clearly intended.

‘You and Óskar?’ Ásta asked. ‘Surely it must be cramped for the two of you?’

‘It’s a change, but that’s life. Reynir’s going to live up here, and it’s his house, of course.’ She was quiet for a moment.

‘We’re just grateful to be able to stay,’ Óskar broke in, surprisingly. ‘We’re fond of the point, in spite of everything.’ He turned and stared hard at Ásta. His face was craggy, his hands bony. She saw immediately the sincerity in his face.

‘I just assumed that you’d still have your space in the apartment up here, considering you brought me into the living room,’ Ásta said awkwardly, even though their discomfort did give her some quiet amusement.

‘No, no. We use the apartment up here when we eat together, all three of us, or when we have guests. The living room downstairs is darker than up here, not much good for entertaining,’ Thóra smiled.

‘I can imagine,’ Ásta replied, speaking from her own experience of living in a dim basement flat.

‘But I’ve done what I can to make it more comfortable,’ Thóra said, almost by way of an apology.

Óskar had turned back to the piano and began playing the same tune as before.

Ásta looked around. The living room had hardly changed, although it certainly seemed smaller than before. As far as she could see, the same furniture was still where it always had been: the old Tudor-style sofa, the dark-brown wooden coffee table, the heavy bookshelves filled with Icelandic literature. The familiar smells played with her senses, creating an elusive aroma and feeling that were a part of the house. How remarkable it was that a smell could evoke long-forgotten memories. The handsome furnishings brought home to Ásta how bland, how depressing, her own apartment was with its cheap furniture – a ripped sofa, a table that she’d bought for almost nothing through an internet ad and the old kitchen chairs in a glaring yellow that had long gone out of fashion.

‘You’ll use your old room up in the attic, naturally,’ Thóra said quietly.

‘Really?’ Ásta asked in surprise. She hadn’t discussed the details of where she’d sleep when she had spoken to Reynir.

‘Unless you’d prefer not to? We can put you up somewhere else.’ Thóra looked nonplussed. ‘Reynir thought that’s where you’d want to be. We’ve stored stuff away up there these last few years, but we moved the boxes and things into the bedroom…’ She looked down suddenly and hesitated. ‘…Into the bedroom that was your sister’s.’

‘It’ll be fine,’ Ásta said decisively. ‘Don’t worry about it.’ It had not occurred to her that she would be able to stay, or would need to stay, in her old room. She would probably have preferred to be somewhere else, but she didn’t want to ask; she needed to be strong.

‘Don’t take it the wrong way, my dear,’ Thóra said with unaccustomed warmth. ‘Although I said that your father wouldn’t have wanted you to come back here, you’re always welcome.’

Generous of you, considering it’s not your house, Ásta wanted to say, but kept quiet. ‘So what do you do here now?’ she asked instead, and not particularly courteously.

‘Much the same as ever … looking after the house. There isn’t as much to be done as there used to be, and we’re not as young as we were. Óskar’s a sort of caretaker, like in the old days. Isn’t that right, Óskar?’

He stood up from the piano and came over to them, supporting himself with a stick. ‘I suppose so,’ he mumbled.

‘He can’t do heavy work anymore, as you can see,’ Thóra said with a glance at the stick. Óskar sat next to her but kept a distance. ‘Broke his knee climbing those damned rocks.’

‘It’ll sort itself out sooner or later,’ Óskar muttered.

Ásta’s attention wandered from what Thóra was saying as she looked at the pair of them. The passing years had taken their toll, and the brother and sister seemed older and more worn than she had expected they would be. Like they’d just about had enough, she mused.

‘And he looks after the lighthouse as much as his bad knee will let him. Took over from your father.’

Ásta was overwhelmed by a feeling of discomfort. It happened occasionally; she inhaled deeply, closing her eyes as a way of slowing her breathing.

‘Are you tired, my dear?’ Thóra asked.

Ásta was taken by surprise. ‘No. Not at all.’

‘Should I make something for you to eat? I cook for Reynir when he’s here. Of course, he can look after himself, but I try and make an effort. It isn’t as if he needs us any longer; he could throw us out to fend for ourselves if he felt like it.’ She smiled. ‘I’m not saying he would, just that he could…’

‘Thanks,’ Ásta said as she regained her composure. ‘I had a sandwich on the way. That’ll keep me going.’

Someone banged hard on the door and Ásta jumped. The elderly pair didn’t seem surprised, though.

‘I thought Reynir wasn’t coming until tomorrow night?’ Ásta asked.

‘He doesn’t make a habit of knocking,’ Óskar mumbled.

‘It must be Arnór, then,’ Thóra said, getting to her feet.

Her brother sat immobile, staring into the distance and holding his knee, probably the damaged one, with a half apologetic look on his face. ‘You remember Arnór?’ he said in a low voice.

Ásta gave the old man a warm smile, thinking of him as old, even though he could hardly be seventy. He certainly looked older, without the lively spark in his eyes that had once been there.

She had always liked Óskar. He had been good to her, and on evenings when there had been fish for dinner, he’d made a point of bringing a glass of milk and some biscuits up to her room before bed. He knew that, despite the sea being so close by, or maybe because of it, little Ásta had never been able to stomach fish. She remembered the nausea she always suffered when there was fish on the table.

‘Thank you,’ she said to Óskar, having meant to say nothing more than a simple ‘yes’, and that of course she remembered Arnór.

‘Thank you?’ Óskar said, questioningly, still holding his knee and leaning towards her as if he had misheard and wanted to be sure not to let it happen again.

Ásta felt her face redden, something that rarely happened.

‘I’m sorry. I was just thinking, you know, about the old days. You always used to bring me milk and biscuits … But, yes, I remember Arnór.’

Arnór lived on a farm nearby. He was Heidar’s boy, although he must be no more a boy now than Reynir was, despite being ten years younger. She could see him in her mind’s eye; a few years older than her, tall and chubby, he had been a shy and clumsy lad. The sisters had seen him around a lot, but he had never played with them. Maybe he thought it was silly to be playing with younger kids, especially girls; or maybe he was just shy.

She thought she saw a light in Óskar’s eyes. He looked at her fondly and then dropped his gaze. ‘So you remember, do you?’ he said. Then added, ‘It’s good to see that you’ve turned out so well.’

She smiled out of pure courtesy. Turned out so well? she thought and felt she could hardly agree with the sentiment. It was clear that he had no notion of the monotonous existence waiting for her back in that miserable apartment in Reykjavík; the unrelenting struggle to break free of the humdrum and do something with herself. She felt so depressed some evenings, lying on the sofa and staring into the darkness beyond the window, watching people hurry along while life passed her by, that she desperately wanted to break out of her own apartment – smash the windows and crawl out, scratched and bloody from the broken glass. That would make her feel something; and that would have to be better than feeling nothing at all.

‘He still lives in the same place?’ She could hear the murmur of conversation from the hall: Thóra and her visitor talking.

‘Oh, yes. He took over the farm after his father died a few years ago. Heidar was an old man by then, bless him. Arnór looks after Reynir’s horses for him. And he helps us out a lot here, especially with the lighthouse. I’m supposed to be the lighthouse keeper, but you can see that I’m past climbing all those stairs. He’s a good lad,’ Óskar concluded, with emphasis.

She looked up as Thóra and Arnór came into the living room, and saw a young man, tall and slim, with the older woman. She almost didn’t recognise him; it was only because she knew who he was that she could see the resemblance behind the bright smile. Otherwise, he had changed completely. He had become a handsome man – it was hard to see in him the clumsy boy she remembered.

‘Ásta,’ he declared confidently, as if he had seen her only the day before, out on the point, perhaps. Back then he was silent and hesitant, the sisters scampering around him as if their lives depended on it. Now he was self-assured. ‘Good to see you,’ he said.

As she stepped towards him, she put out a hand, intending that he should shake it. Instead she found herself being hugged affectionately. His embrace was so warm, she couldn’t help responding, automatically drawing him closer. Then, realising what she was doing, she pulled away, uncertain.

She looked at him awkwardly and said, ‘Good to see you too,’ almost in a whisper, following it with a shy smile.

There was nothing awkward about Arnór, though. He stood stock still while she fidgeted and wondered where to look.

It occurred to her to say something about his father, to offer condolences, but she decided against it. She had no idea how long ago Heidar had passed away, or how, so she would have sounded insincere. Her own father had also died since the last time she had seen Arnór. Maybe those two deaths could cancel each other out? Neither she nor Arnór needed to mention them.

He glanced at Óskar. ‘I brought the tools, so shall we have a quick look at that window in the lighthouse? We need to fix it soon.’

‘It broke in the bad weather yesterday,’ Óskar said to Ásta before turning to Arnór. ‘Of course, not that I’ll be a lot of help.’

‘You’d better come anyway. I’ll need you to show me what needs doing,’ Arnór said, so politely that Ásta was almost convinced he was sincere, although she was sure he was just trying not to hurt Óskar’s feelings.

The two men left Ásta and Thóra standing wordlessly in the living room.

‘I think I’ll go up to bed,’ Ásta said finally, when the silence had become too awkward. She picked up her case.

‘All right,’ Thóra said. ‘The stairs to the attic—’

Ásta interrupted her. ‘I know the way,’ she said in a heavy voice.

III

She switched on the light and the weak bulb illuminated the narrow staircase, the walls grey and decorated with a tree-branch pattern. A closer look showed a few red berries on the green boughs. The carpet was worn and the wooden handrail was past its prime. From somewhere came a slight draught – enough to set her shivering again.

She knew that there were plenty of other unoccupied rooms in the house. She didn’t have to agree to stay in her old attic room. But, in spite of everything, it had been her room, and she wasn’t one to imagine that any lingering ghosts from her past were going to keep her awake. She was stronger than that. Once she was up in the attic, however, standing in front of the room’s closed door, she wondered if she was doing the right thing. Was this a mistake? She had an uncomfortable feeling that it was all going to end badly. Wouldn’t it be better to leave old stones unturned and go back home?

It wasn’t too late. She could easily turn around, go downstairs and say goodbye to Thóra, telling her that something had come up in Reykjavík that meant she had to go. There would be no need to say anything to Óskar or Arnór.

She hesitated before opening the door and looked around. To the right were the doors to the main bedroom and the little bathroom. Behind Ásta was the corner that served as a kitchen and … she turned very slowly. The door to her sister’s bedroom was shut. She wanted to look inside, just for a moment, but decided against it. Instead she opened the door to her old bedroom.

The attic room wasn’t as large as it had been in her memory. There was nowhere she could stand upright anymore. The air was stuffy, with an almost mouldy scent to it, so she hurried to switch on the light and open the window.

That was better. The mutter of waves drifted in through the window, familiar and calming. She looked out and down at the edge of the cliff. Here, from this very window, she had seen something she shouldn’t. Oddly, it didn’t seem painful to recall it, even though the shock of it had been devastating.

There wasn’t much to see in the evening gloom. The lighthouse on the point helped, though. Darkness never had the upper hand here, she thought, but then smiled grimly. In this house, and in this place, there was nothing but darkness.

The house seemed uncomfortably quiet. Thóra must have gone down to her rooms in the basement. Moving must have been difficult for her, but Ásta struggled to feel any sympathy for the old woman.

Her old bed was in the same place. Fortunately, even though it wasn’t exactly big, it wasn’t a child’s bed. Still fully clothed, and leaving the light on, she lay down cautiously. The bed creaked loudly, as it always had. Ásta made herself more comfortable, the bed groaning beneath her.

Physically she was exhausted, but her mind was buzzing, and sleep was unlikely to come straightaway, so she got up again, remembering the steep spiral staircase that led from the little attic flat, if it could be called that, straight down to the back door and out into the open. Trying to throw off her fatigue, she went down the stairs. This had been a lot of steps for small feet all those years ago. But it was no distance at all now, and within a moment she was stepping out into the gently falling snow.

She took slow strides away from the house and out into the darkness, not because of the snow underfoot but due to the weight of so many memories. She inhaled and the cold air brought back even more, sudden and sharp now: those nights spent in the little attic room with the calls of the gulls and the rolling crash of waves preventing her from falling asleep. In fact, the sound of the sea was less a memory, more an all-encompassing presence that now rumbled in competition with the wind.

Once more she had the feeling that coming to this place was tempting fate. But making an effort to shake off her disquiet, she began to make her way to the lighthouse.

The path was difficult to make out in the darkness. Not that it mattered – Ásta could have found the way blindfold. And she wasn’t afraid of the dark, never had been. Yet still she felt uneasy, as if the ghosts of the past were calling out to her, following her … warning her. Soon the lighthouse began to emerge gradually from the gloom in front of her, on the high ground of the point. She had spent a lot of time around this tall building, sometimes basking in the sunshine under its southern face, more often in the cold shadow of the northern side.

She would have liked to walk right up to the lighthouse, but Óskar and Arnór were there, repairing the window and she had no desire to meet them. So instead she made her way towards the rocks to her left – a steep escarpment that weather, wind and sea had ravaged into jagged boulders over the centuries.

Before she knew it, she was at the cliff edge. She leaned forwards, holding her breath and gazing down as the wind buffeted her face and the snow stung her skin. Below was the unforgiving sea, illuminated by the lighthouse, and straightaway she felt the presence of death.

A strong gust all but pushed her off the edge of the cliff. She backed away, having no intention of ending her life here. All the same, she was not frightened; she enjoyed the feeling of blood pulsing through her veins. The thought of death had brought a sudden rush of energy.

The sea had always mesmerised her. Sometimes she had sat here on the clifftop and watched it, sometimes going down to the beach in the bay. When the waves were at their greatest and most fierce, there was no place she would rather be. White was the colour of an angry sea, and thus, little by little, in the small girl’s eyes, white had become the colour of anger. Standing close to the waves in a violent storm, the salty sea would fill her being – she would become almost at one with the ocean. She remembered well now how she had watched spellbound as the gulls fought with the gusts of wind, trying with all their strength to stay in the air. Often she knew just how they felt.

Turning away at last, she started walking back to the house. As she went, she took a last glance at the lighthouse and saw Óskar and Arnór coming the same way. They saw her immediately and Arnór waved. She hesitated, waved back and then hurried onwards.

Back in her room, she drew the curtains, pulled on a sweater to drive out the chill and stretched out under the duvet. It was pitch dark now, but still she tossed and turned before finally managing to fall asleep.

She awoke suddenly, unsure how long she had slept, and had the feeling that she was struggling to breathe. She opened her eyes but the darkness overwhelmed her. She sat up with a jerk, breathing short, shallow breaths. It was far too hot, the air was heavy and stifling.

Pulling off the sweater and her shirt, she pushed the duvet off and sat there for a moment in her underwear, before reaching out to draw back the curtains and open the window. Cold air rushed in and the darkness was lifted as the lighthouse flooded the room with light.

She lay back on the bed, wondering for a moment whether to fetch her mobile phone from the pocket of her jeans to check the time. But time didn’t matter, she decided. She closed her eyes, her breathing returning to normal once more, and settled into a new calmness. She wasn’t used to sleeping with an open window these days – it just wasn’t possible in her basement flat – but now the fresh air came like a saviour, and finally she fell asleep, the memories of the past leaving her in peace, allowing her to sleep soundly.

IV

The next day passed uncomfortably slowly. Ásta slept in late and ate a midday meal with Thóra and Óskar in an almost overpowering silence. Reynir had still not arrived and Arnór had not made another appearance. After lunch she went for a short walk and then tried to rest in the attic, but with little success. There was too much on her mind.