Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Dark Iceland

- Sprache: Englisch

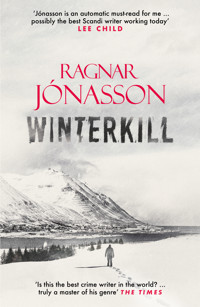

THE STUNNING FINAL INSTALMENT OF THE MULTI-MILLION-COPY BESTSELLING DARK ICELAND SERIES *Sunday Times BOOK OF THE MONTH* `Jónasson is an automatic must-read for me … possibly the best Scandi writer working today´Lee Child `Is this the best crime writer in the world today? … Truly a master of his genre´The Times `The engaging Ari Thor returns in this darkly claustrophobic tale. Perfect mid-winter reading´ Ann Cleeves `A stunningly atmospheric story. Ari Thór Arason returns in this pitch-perfect, beautifully paced crime novel … Ragnar Jónasson is at the top of his game, and a master of the genre´ Will Dean _______ A blizzard is approaching Siglufjörður, and that can only mean one thing… When the body of a nineteen-year-old girl is found on the main street of Siglufjörður, Police Inspector Ari Thór battles a violent Icelandic storm in an increasingly dangerous hunt for her killer … The chilling, claustrophobic finale to the international bestselling Dark Iceland series. Easter weekend is approaching, and snow is gently falling in Siglufjörður, the northernmost town in Iceland, as crowds of tourists arrive to visit the majestic ski slopes. Ari Thór Arason is now a police inspector, but he's separated from his girlfriend, who lives in Sweden with their three-year-old son. A family reunion is planned for the holiday, but a violent blizzard is threatening and there is an unsettling chill in the air. Three days before Easter, a nineteen-year-old local girl falls to her death from the balcony of a house on the main street. A perplexing entry in her diary suggests that this may not be an accident, and when an old man in a local nursing home writes `She was murdered´ again and again on the wall of his room, there is every suggestion that something more sinister lies at the heart of her death… As the extreme weather closes in, cutting the power and access to Siglufjörður, Ari Thór must piece together the puzzle to reveal a horrible truth … one that will leave no one unscathed. Chilling, claustrophobic and disturbing, Winterkill is a startling addition to the multi-million-copy bestselling Dark Iceland series and cements Ragnar Jónasson as one of the most exciting and acclaimed authors in crime fiction. _______ Praise for Ragnar Jónasson `A sinister twisted tragedy´ The Times 'If Iceland missed out on the Golden Age of crime writing, the country – and Jonasson – is certainly making up for it now´ Sunday Times `Outstanding … Series fans will be sorry to see the last of Ari Thór´ Publishers Weekly `Jonasson's Dark Iceland novels are instant classics' William Ryan `Jónasson's punchy, straightforward prose is engrossing … A diverting mystery´ Foreword Reviews `Consummate crime writing … poignant and disturbing´ New Books Magazine `Chilling, creepy, perceptive, almost unbearably tense' Ian Rankin `A tense, gripping read´ Anthony Horowitz `Icelandic noir of the highest order, with Jónasson's atmospheric sense of place, and his heroine's unerring humanity shining from every page´ Daily Mail `Ragnar Jónasson writes with a chilling, poetic beauty´ Peter James `Traditional and beautifully finessed´ Independent `Jónasson's true gift is for describing the daunting beauty of the fierce setting' New York Times `A chiller of a thriller´ Washington Post `Jónasson's books have breathed new life into Nordic noir´Express

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 301

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

Easter weekend is approaching, and snow is gently falling in Siglufjörður, the northernmost town in Iceland, as crowds of tourists arrive to visit the majestic ski slopes.

Ari Thór Arason is now a police inspector, but he’s separated from his girlfriend, who lives in Sweden with their three-year-old son. A family reunion is planned for the holiday, but a violent blizzard is threatening and there is an unsettling chill in the air.

Three days before Easter, a nineteen-year-old local girl falls to her death from the balcony of a house on the main street. A perplexing entry in her diary suggests that this may not be an accident, and when an old man in a local nursing home writes ‘She was murdered’ again and again on the wall of his room, there is every suggestion that something more sinister lies at the heart of her death…

As the extreme weather closes in, cutting the power and access to Siglufjörður, Ari Thór must piece together the puzzle to reveal a horrible truth … one that will leave no one unscathed.

Chilling, claustrophobic and disturbing, Winterkill marks the startling conclusion to the million-copy bestselling Dark Iceland series and cements Ragnar Jónasson as one of the most exciting authors in crime fiction.

iiiiiivv

Other books in the Dark Iceland Series

Snowblind

Nightblind

Blackout

Rupture

Whiteoutvi

ix

Ragnar Jónasson

Winterkill

Translated from the French edition by David Warriner

xi

To all the friends of Ari Thór who asked me to write one more book about him

‘Then all the ills of winter are swept away.’

Þ. Ragnar Jónasson (1913–2003)Stories from Siglufjörður, 1997 (Trns. Quentin Bates)

xii

Pronunciation guide

Icelandic has a couple of letters that don’t exist in other European languages and which are not always easy to replicate. The letter ð is generally replaced with a d in English, but we have decided to use the Icelandic letter to remain closer to the original names. Its sound is closest to the voiced th in English, as found in then and bathe.

The Icelandic letter þ is reproduced as th, as in Thorleifur, and is equivalent to an unvoiced th in English, as in thing or thump.

The letter r is generally rolled hard with the tongue against the roof of the mouth.

In pronouncing Icelandic personal and place names, the emphasis is always placed on the first syllable.

Ari Thór – AH-ree THOE-wr

Baldvina – BALD-veena

Bjarki – BYAHR-kee

Bolli – BOD-lee

Dóra – DOE-ra

Eggert – EGG-gerrt

Gudjón – GVOOTH-yoen

Hávardur – HOW-varth-oor

Hersir – HAIR-seer

hnútar – HNOO-tar

Hrólfur – HROEL-voor

Jenný – YENN-nee

Jóhann – YOE-han

Jónína – OE-neena

Kristín – KRIS-teen

Ögmundur – UGG-moon-door

Rósa – ROE-ssa

Salvör – SAL-vur

Sara – SAH-ra

Selma – SELL-ma

sírópskökur – SEE-roeps-KUR-koor

Stefnir – STEB-neer

Svavar – SVAH-var

Thorleifur – THOR-lay-voor

Thormódur – THOR-moe-thoor

Tómas – TOE-mas

Ugla – OOG-la

Unnur – OON-noor

Víkingur – VEE-kingg-oor

CONTENTS

HOLY THURSDAY

1

‘Police, Inspector Ari Thór Arason speaking.’

The emergency operator cut to the chase: ‘We’ve just received a call from Siglufjörður; are you the duty officer tonight?’

Night and day were much the same in Siglufjörður in summer, when the sun barely set at all. It was Ari Thór’s favourite time of year. It was just a couple of months away now, and for him, it couldn’t come soon enough. He loved the sense of infinite freedom that came with the long hours of daylight in the north of Iceland.

It was a far cry from the darkness and snow that blanketed the town in winter.

Ari Thór was wide awake when the phone rang. He couldn’t sleep, no matter how hard he tried. He was still using the master bedroom in his place on Eyrargata. The same room he had shared with Kristín and Stefnir before she and the little one moved to Sweden.

He had found it hard to adjust when he first moved there from Reykjavík, but the blizzards and gloomy days no longer brought on the same feeling of claustrophobia. He hardly ever felt homesick anymore. In recent years, Siglufjörður had 2experienced the ripple effects from the new wave of prosperity that was sweeping across southern Iceland in the wake of the financial crisis. Now, tourists from all over the world flocked to the small town every summer. Even in winter, people came to enjoy the local ski slopes, most of them from other places in Iceland. Easter had become an especially popular time for visitors, and now, on the eve of the long weekend, it looked like the slopes were going to be busy.

Ari Thór was in his thirties now, but he felt that his life was back at square one. He lived alone and he hardly saw his son anymore. He couldn’t imagine being able to salvage what was left of his relationship with Kristín. They had exhausted all the options, so to speak.

Truth be told, he had settled into a comfortable routine and he was reluctant to do anything that might rock the boat. He had been promoted to inspector in Siglufjörður after years of aspiring to the role, so he was now in charge at the police station. At some point, he would have to decide whether he was happy with what he had achieved. He knew that it would be hard for him to go any further if he stayed in Siglufjörður, that was if he decided to keep climbing the rungs of the career ladder. It wasn’t just that he had reached the most senior rank at the small-town police station; it was the fact that, even if he excelled in his current position, there were no higher-ups close by to see his good work.

Tómas, his old boss, had left Siglufjörður and moved south to take up a position in Reykjavík. For a while now, he had been encouraging Ari Thór to follow his example, saying Ari Thór should let Tómas know when he was ready to do the same, and he would put in a good word for him. Ari Thór wasn’t sure the offer still stood, however, as it had been a long time since Tómas had mentioned it. And he was all too aware 3that Tómas wasn’t getting any younger and must be close to retirement. Soon, Ari Thór would lose his only advocate at police headquarters in Reykjavík. Once that door closed, he might be stuck up north for good, whether he liked it or not.

Ari Thór’s consternation about his future tended to prey on his mind in the dead of night, and now was no exception. When the sun came up, though, he always managed to clear his head, resolving to keep taking one day at a time. But he knew the clock was ticking. Soon, he would have to make up his mind. Maybe he would decide that he was right where he wanted to be, here in Siglufjörður. He still needed to give the matter some serious thought.

There would be no time to dwell on the question over the Easter weekend, however. He would be too busy doting on little Stefnir. Ari Thór’s heart was already skipping a beat at the thought of seeing him again, even though it was just for a few days. His son had turned three at Christmas, but Ari Thór had missed out on all the celebrations.

Six months earlier, Kristín had made the decision to further her medical training by going to university in Sweden. Ari Thór didn’t hold it against her. Iceland provided excellent training in general medicine, but like many doctors, she wanted to become a specialist, and the time had finally come for her to stop putting things off and pursue her ambition, and that meant studying abroad. As Kristín’s plans became clear, she and Ari Thór had discussed Stefnir’s future in light of the move. Kristín had suggested that she take the boy with her ‘in the beginning’; they could think about other options down the line. She had promised to bring Stefnir back to Iceland at Christmas and at Easter, perhaps more often, and Ari Thór had been planning to take holiday time in the summer to see them in Sweden. He hadn’t objected, despite 4the terrible sense of dread that filled him at the thought of seeing his son so rarely. He wanted to avoid any kind of conflict with Kristín.

Ari Thór tossed and turned in bed, trying to get comfortable. Curling up on his side, he took a deep breath and released it with a long sigh. He had to get some sleep. Tomorrow – no, today, he corrected himself – was Thursday, and his last day on duty before the long Easter weekend. Kristín and Stefnir would be arriving that evening.

It was nearly three in the morning. More than two hours since he had gone to bed, and he was still wide awake.

Eventually, he admitted defeat and got up.

Damn it. He couldn’t afford a sleepless night, not now, when he was supposed to be ready to enjoy a weekend with his son. But anxiety only fuelled the fire of sleeplessness, and now he didn’t even feel tired anymore.

There wasn’t much furniture in the bedroom besides some shelves filled with old books that the former homeowners hadn’t bothered to take with them. Ari Thór had sometimes leafed through the pages of these volumes, mostly when he was trying to sleep and needed some distraction from his thoughts. He plucked a book from the shelf, almost at random, and laid his head on the pillow again.

Try as he might, Ari Thór couldn’t shake a niggling feeling of apprehension about the weekend ahead. For the first time, he was leaving the station in the hands of Ögmundur, a young recruit who had moved north for his first posting. What he lacked in experience, he more than made up for with his eagerness to learn.

Since Ari Thór had taken on the inspector’s post, he had been forced to make do with temporary replacements and officers seconded from Ólafsfjörður or Akureyri – never the 5same person from one case to the next. But recently, he had received approval to hire an officer for a full-time position. There had been no shortage of interest in the job, and some of the applicants boasted a wealth of experience, but Ari Thór had chosen to hire this young man, who was fresh out of police training school.

In spite of their difference in character, Ari Thór saw something of his younger self in Ögmundur. He remembered how Tómas had shown him the ropes when he first came to Siglufjörður. Now the tables were turned, and Ari Thór was the experienced officer putting the young rookie through his paces. He had to admit, though, that he had struggled to build the rapport with Ögmundur that Tómas had built with him, in spite of there being a narrower age gap between them.

After trying to find sleep in the pages of a book for what seemed like an age, Ari Thór went down the rickety old stairs to the kitchen. There, he poured himself a glass of water and snacked on a piece of dried fish as he flicked through yesterday’s newspaper. He shouldn’t have bothered; there was nothing new in there, just the same rehashed stories. The only thing that really caught his eye was the weather forecast. It wasn’t great. It looked like heavy storms were expected in the north right after the Easter weekend. That was the thing about winter up here; no sooner had you dug yourself out after one blizzard than you had to prepare for the next one.

He really couldn’t afford a sleepless night; he wouldn’t last the day.

Ari Thór was on call, but more often than not, the streets of the little town were deserted overnight and the police station was a haven of calm. Usually the only calls were complaints about drunks making too much noise on their way home.6

Ari Thór had gone back to bed – but was still wide awake – when the phone rang.

‘A passerby has found what seems to be the body of a young woman lying in the street. An ambulance is on the way, just in case,’ the operator at the emergency call centre said in a neutral tone.

Ari Thór hurriedly pulled his uniform on, pinning the phone to his ear with his shoulder.

‘Where?’

‘On the main street, Aðalgata.’

‘Who made the call?’

‘The man’s name is Gudjón Helgason. He said he would stay on the scene until the police arrived.’

The name didn’t sound familiar.

Two minutes later, Ari Thór was fully dressed and stepping outside into the night. He lived just around the corner from the main street, so it would only take a moment for him to get there on foot. It was a frigid, windless night and the stars were sparkling in the sky. Nature up here was always wild and unbridled, but at this time of year, there was something not just darker about it, but somehow deeper and more distant.

Ari Thór arrived on the scene at the same time as the ambulance. As he turned onto Aðalgata, a shiver ran down his spine.

On the edge of the pavement, a young woman was lying in a pool of her own blood, her body twisted into so unnatural a position, there was little doubt that she must have plunged from a great height. It didn’t take a doctor to figure out that she was dead. It looked like all the blood had come from her head; her skull was likely fractured.

As Ari Thór approached the body, he realised the woman was probably even younger than he had first thought – 7possibly still in her teens. He drew in a sharp breath as he saw her face.

Oh, hell.

Her gaze was eerily absent, her eyes wide open but empty, as if staring into nothing.

Ari Thór immediately knew it was a sight that would haunt him forever.

2

Ari Thór was no stranger to wandering the streets at night. It didn’t matter if it was the height of summer or the dead of winter, there was something magical about the experience of going for a stroll when no one else was around. The town always seemed so peaceful under the blanket of nocturnal silence. For a brief moment, he had that familiar sense of floating in the peaceful calm, but the gravity of the situation returned and shattered the stillness.

The few people on the scene seemed to be awaiting his orders, all except the doctor from the hospital, who was already crouching beside the young woman’s body. Other than the doctor, Ari Thór saw two paramedics, and, behind them, a man who looked to be in his thirties, wearing a down jacket and a woolly hat and sporting a full beard – presumably this was Gudjón, the man who had called the emergency services.

Ari Thór felt like he was frozen to the spot. Now more than ever, he was aware of the weight of the responsibility on his shoulders. Since he had been promoted to inspector, life in Siglufjörður had followed its usual uneventful course and, to his great relief, he hadn’t had any major crimes to deal with. Days came and went with a comforting lack of excitement as the police were called to deal with nothing more serious than the occasional report of drug use, highway-code violations or night-time noise. But now this young woman had been found dead in the middle of the main street. Ari Thór looked at her again before lifting his gaze to take in the surroundings.9

The lifeless body was lying on the pavement in front of a two-storey house with dormer windows in the roof, suggesting a third level of living space in the attic. It looked like there was a rooftop balcony as well. Ari Thór’s first thought was that the young woman must have fallen from up there, as chilling as that prospect was.

The doctor stood up. Her name was Baldvina, and she had only been in Siglufjörður since the beginning of January. Doctors never stayed around here for very long. Turnover at the hospital had been high in recent years, with one doctor after another moving on to better things in bigger places as soon as an opportunity came along, or leaving to pursue further training, like Kristín had done. Baldvina was a little younger than Ari Thór. He had the sense that she was competent, based on the few times their paths had crossed.

‘Well, she’s certainly dead. Most likely as a result of her fall,’ Baldvina said, turning to look up at the roof of the building, pre-empting Ari Thór’s question. ‘I suspect she fell from that balcony up there. But that’s something for you to find out, of course. Is it all right for us to move the body?’

Ari Thór felt a knot in his stomach. This was the first violent death he would have to investigate as the officer in charge. He was anxious to do things properly.

‘Yes, but just let me take a few photos first. And we’ll also have to secure the scene for forensic examination.’

Ari Thór knew it would take a while for the forensics team to travel to Siglufjörður. But he couldn’t bring himself to let the poor young woman wallow here in her own blood for longer than she had to. It was a matter of respect. He didn’t want to leave her body exposed for all to see. This was the main shopping street in town, and the sun would soon be rising. He was also wary of any curious night-birds who 10might be attracted by all the unusual activity and swoop in for a closer look.

Ari Thór used his phone to take some photos of the scene. Then he called Ögmundur to let him know what had happened. ‘I need you to come and join me on Aðalgata as quickly as you can.’

‘Yes, er, of course,’ his half-asleep junior officer replied after a brief moment of hesitation.

Ögmundur had shown himself to be positive by nature and seemed keen to embrace any challenge, though in all honesty his workload so far had not been particularly demanding. Not only had it been an uneventful winter, Ari Thór had also spared his new recruit some of the more mundane duties of the job, preferring to let him settle in at his own pace. Somehow, though, Ögmundur had already managed to make more friends in Siglufjörður than Ari Thór had in all the years he had lived here. The young rookie seemed to be very quick to earn people’s trust – obviously a desirable quality in this job. It also turned out that Ögmundur had played for the Icelandic national football team – the junior team, in fact, but that made no difference to Ari Thór – and his enthusiasm for the sport, a popular topic of conversation around these parts, made it easy for him to engage with people.

Ari Thór explained the situation to Ögmundur on the other end of the line. ‘She must have fallen from the rooftop balcony,’ he added. ‘We don’t know yet if it was an accident or if it was, er … suicide. That’s what we’ll have to find out. And time is of the essence.’

On receiving Ari Thór’s go-ahead, the paramedics lifted the lifeless body of the young woman onto a trolley and rolled it into the ambulance, leaving nothing but a gruesome red pool 11on the pavement, a chilling remnant of what had happened. Under the glow of a streetlight and amidst the shadows of the night, the blood looked almost too bright to be real. For a second Ari Thór thought the scene looked like a theatre set.

Now he turned to the man who had been standing in the background, barely moving a muscle, keeping his head down. ‘Good evening. You must be Gudjón?’

The man nodded before murmuring a hesitant ‘yes’.

‘I’m Inspector Ari Thór Arason. Can you tell me what happened? Was it you who called the police?’

‘Yes. Well, I called the emergency number, but I didn’t really know what to say. I don’t have a clue what happened.’

The words seemed to make him short of breath. He kept rubbing his beard as he spoke, and his eyes darted from side to side, without meeting Ari Thór’s.

Ari Thór listened and waited. It was too soon to launch straight into another question. Experience had taught him that people who were nervous, as Gudjón seemed to be, tended to fill a silence.

‘I just, well, found her like that, just lying there. At first I thought she had fallen. Slipped and fallen on the street, I mean. I went over and was about to help her get up when I noticed … when I realised she was dead. Then I called the emergency services – straight away.’

‘Did you touch anything?’ Ari Thór asked after a brief pause.

‘I … I can’t remember. Maybe I gave her a little shake to make sure, but it seemed so obvious that she was dead.’

Ari Thór nodded. ‘Did you notice anyone else in the vicinity?’

‘No, there was no one else around. Only me. It was quite a shock to see her lying there. Do you think she jumped?’12

‘It’s hard to say right now,’ Ari Thór replied, then pursued his line of questioning. ‘It’s four in the morning now, so you were out and about at around three-thirty, is that correct?’

‘Yes, yes, that’s right.’

‘Why was that?’

‘I was just out for a walk, that’s all.’

‘In the middle of the night?’ Ari Thór raised an eyebrow.

‘I find the cold invigorating. The skies are clear, and there’s not a breath of wind, just the fresh sea air to fill your lungs. It’s a joy to wander the streets in this weather.’

Ari Thór wasn’t convinced, though, to be fair, he often went for a walk around town after dark, too – not that he was going to admit that to Gudjón. There was something about the silence that descended on these streets in the dead of night. That damned, elusive silence.

‘Day and night?’

‘I prefer to walk at night. It’s quieter. More soothing for the soul.’

‘Do you live in Siglufjörður, Gudjón?’

Gudjón hesitated.

‘I do at the moment, yes. I’m here for three months, on an artist’s retreat.’

‘And where are you staying?’

‘There’s an artist’s residence not far from here, on the waterfront, just on the edge of town.’

‘And have you been here long?’

‘Since January,’ Gudjón replied. Now he seemed to be feeling the chill of the night. It looked like it was making him uncomfortable.

‘I see,’ Ari Thór said, marking a pause. ‘What’s your discipline?’

‘What do you mean?’13

‘What’s your artistic discipline? Painting, or music, for example.’

‘Painting. Yes, painting. Well, I paint, and I draw. Perhaps you saw the posters for my exhibition the other day. Landscapes of Siglufjörður. They’re all for sale.’

‘No, I must have missed those. Do you know her?’

‘Who?’

‘The dead woman.’

Gudjón shivered. ‘What? No, of course not. I have no idea who she is … er, was. Why would I know her? I’m not from round here.’

‘What makes you so sure she was a local?’

‘I … well, how am I to know? I don’t know what you’re insinuating. All I did was call the police. I’ve never seen that young woman before.’

‘You have to admit, Gudjón, it’s a bit strange to be wandering around in the middle of the night.’

‘I’m an artist, for heaven’s sake!’ he protested, as if that word could justify all manner of quirks and sins. His breath was coming in fits and starts, and he was struggling to string his words together. ‘Look, I walk the streets at night to find inspiration, then I go home and I draw. I sleep in the daytime. You’re welcome to … come over and look at my work if you like. That way you’ll see I’m not lying to you.’

‘That won’t be necessary for now, but I’m sure I’ll be in touch as the investigation progresses,’ Ari Thór explained. ‘However, I would ask that you come by the station later today so we can take a formal statement.’

Gudjón’s reluctance was palpable. ‘Is that really necessary? I’ve got nothing to hide, but to be perfectly honest, I have absolutely no desire to be grilled by the police any more than I have been already.’ Still struggling to catch his breath, he 14added: ‘The only … the only thing I did was my civic duty, when I picked up the phone to call you, all right?’

‘Listen, a young woman – perhaps she was still just a teenager – is dead, and you discovered her body. We have to take your statement for the purposes of the investigation. We have no reason to assume that you might have somehow been involved in her death.’ Ari Thór was reluctant to sugar-coat his words too much; he still wasn’t entirely satisfied with Gudjón’s explanation.

‘Well, I certainly hope you’re not going to accuse an innocent bystander of any wrongdoing!’

Gudjón was still huffing and puffing when Ögmundur turned the corner onto Aðalgata, at the wheel of his little red Mazda, an older, sporty convertible that could still turn heads. A low-slung car like that wasn’t the most practical in the snow, but after a few days of unseasonably mild temperatures and rain, the streets were clear that night. He parked across the street and ran over to Ari Thór and Gudjón.

‘Sorry to keep you waiting, I came as quickly as I could. Do you think she jumped?’

His eyes darted down to the pool of blood, then up to the balcony on the roof.

‘Thanks, I appreciate it,’ Ari Thór said. ‘This is Gudjón Helgason. He was out for a night-time stroll when he stumbled upon the body. I’ve asked him to come down to the station later. When he does, would you kindly take his statement, Ögmundur?’

‘Of course, I’ll take care of it.’ Ögmundur smiled and 15reached out to shake the man’s hand. ‘Hi, Gudjón. Nice to meet you. My name’s Ögmundur. I’m a police officer here.’

‘That will be all for now. You’re free to go on your way. Thank you for your cooperation.’ Ari Thór dismissed Gudjón with a curt nod.

Ögmundur’s informal tone when speaking to members of the public was something that got on Ari Thór’s nerves, though he had to admit it often helped to loosen their tongues.

‘Enjoy the rest of your walk,’ he added, through gritted teeth.

Hauled out of bed in the middle of the night when he was already deprived of sleep, Ari Thór was struggling to put on as cheerful a face as the young rookie.

3

‘Stay out here,’ said Ari Thór. ‘I want you to call forensics. And keep an eye on the scene until they get here, OK?’

Ögmundur nodded indifferently. ‘If you insist, but I don’t really see the point, Ari Thór. You can see for yourself, there’s nothing but blood on the ground. I’d be better going inside the building to make sure no one goes out onto the balcony.’

Ari Thór stuck to his guns. ‘Just keep an eye on the entrance, all right? I’ll go inside and take a look around the building.’

The front door was locked. Judging by the number of doorbells, the old house had been converted into two flats – one on each floor.

Ögmundur peered over Ari Thór’s shoulder. ‘Do you know the people who live here?’

‘No,’ Ari Thór said, shaking his head. The labels on the doorbells indicated only that the occupants of the ground-floor flat were named Jónína and Jóhann, and that a man by the name of Bjarki lived upstairs.

Ari Thór tried the bell for the downstairs flat. He didn’t have to wait long before the door clicked open. In a doorway at the foot of the stairs stood an elderly man in pyjamas, who seemed wide awake.

‘My wife and I were waiting for you. We’ve been watching what was going on out there,’ the man said with a quiver of hesitation.

Evidently, they must have been standing in the dark, because Ari Thór hadn’t noticed any light in the windows.17

‘So, what happened? Who was that, lying in the street? Are they dead?’

‘Can I come in for a moment?’

‘Oh yes, of course,’ the man replied, extending a limp, clammy hand. ‘I’m Jóhann.’

Ari Thór had a sense of foreboding. Something didn’t seem right here. He followed the man into the gloomy flat and, in the living room, saw the shadow of a woman sitting on a sofa, beside a window that looked out onto the street. Presumably, this was Jónína. She didn’t say a word as he approached.

Ari Thór took the lead. ‘I’m sorry to disturb you. A young woman died here tonight. Did you happen to notice anything?’

‘Nothing at all,’ Jóhann replied decisively. ‘Who was it?’

‘I don’t know yet. Perhaps you have an idea? Is there a young woman or a teenage girl who lives in the building?’

‘No, no, just Bjarki upstairs, but … sometimes he rents the flat out to strangers on Airy … oh, heavens, Jónína, what’s it called again?’

His wife remained tight-lipped. They both looked to be well north of seventy. Ari Thór wished he could pick Tómas’s brain. His old boss had known just about everyone in town – where they worked and who was related to whom.

‘Is he at home at the moment, do you think?’

The couple exchanged a glance.

‘I don’t think so,’ Jóhann replied. ‘He’s always coming and going. He spends a lot of time in Reykjavík. But he’s originally from here. I haven’t seen him for a day or two.’

Jónína finally opened her mouth. ‘No, he’s not at home.’ Her words were quiet but were said with conviction. ‘I would have run into him, or at least heard if he was here.’

‘You can’t see everything, darling. We can’t know all the comings and goings in the building, can we?’18

His words seemed stilted, as if he were trying to send his wife a message. Ari Thór looked out the window and realised that anyone standing there probably wouldn’t be able to see who was ringing the doorbell.

‘When you said he was from here, did you mean him, or his family?’ he asked.

‘Him. He’s a Siglufjörður boy,’ Jónína replied. ‘I remember his father. Bjarki was born here, then the family moved away, like so many others. Once the herring had all gone, there wasn’t much to do around here.’

‘Now, people are coming back and it’s bringing life to the town again,’ Jóhann added.

‘We never left, of course,’ said Jónína, folding her arms across her chest with a frown, as if to signal the end of the conversation.

‘How do you get up to the balcony?’ Ari Thór asked.

‘The balcony? Why do you want to know that?’ Jóhann seemed to have forgotten why the police were there. Then: ‘Oh, yes, of course. Let me show you the way. There’s a door off the attic, up in the eaves. In the old days, that space saw more use than it does now. Bjarki’s grandparents used to live in this house. Then it was converted into flats and we bought the place on the ground floor. We were wanting to downsize, you see. Before we moved in here we had a detached house a bit further out of town, but it was so much work to keep it looking nice. Anyway, they made the attic into a common space for both flats, more of a place to store things than to spend any time. It’s too cold up there to sit around. And we never go out onto that balcony. Jónína has no end of trouble getting up the stairs. And I doubt Bjarki spends much time out there either. He’s always got his nose buried in his books. A fine young man, he is,’ Jóhann added with a smile.19

Again, Ari Thór had the feeling that something wasn’t right about the way the man was talking. It seemed to him that Jóhann was nervous, and was trying to hide the fact by being overly chatty.

Jóhann led the way back to the entrance of the building and motioned for Ari Thór to follow him as he started up the stairs at a snail’s pace. There was a certain old-fashioned charm about the creaky staircase. The time-worn wooden treads were a slightly lighter shade than the handrail, which seemed to have fared better over the years. The walls were decorated with pale-blue wallpaper.

When Jóhann reached the landing, he took a moment to catch his breath and pointed to a door.

‘That’s where the historian lives.’

‘Bjarki? He’s a historian?’ Ari Thór asked.

‘He’s doing some research for the town council about people from Siglufjörður who emigrated to North America. The council must have a bit of money to play with if they can fund a project like that. The economy must be doing all right at the moment, I suppose, with all the road work, tourists and whatnot,’ Jóhann mumbled, trying to gather the strength to tackle the next flight of stairs.

‘I didn’t know people from around here were part of that wave of emigration,’ Ari Thór admitted.

‘Apparently about fifteen thousand Icelanders from all over the country went over there around the turn of the century, and a fair few people from here ended up in Canada – in the province of Manitoba, I think Bjarki said. I’m not exactly a bookworm, but it’s still an interesting research topic, don’t you think? Right, off we go.’

They continued up the next flight of stairs, which ended abruptly at a closed door, with no landing.20

‘Here, let me open it,’ said Ari Thór, keen to prevent someone who wasn’t wearing gloves inadvertently messing up any fingerprints that might be on the door handle. ‘It isn’t locked, is it?’

‘No, it never is.’

Ari Thór gently pushed the door open and tiptoed carefully into the attic room. At first glance, nothing seemed to be particularly out of place. The temperature up here was freezing, though, and Ari Thór soon saw why: the door leading to the balcony was ajar.

‘Wait here, Jóhann, and don’t touch anything,’ he said with authority.