Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

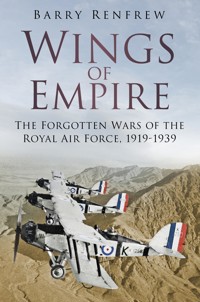

At the end of the First World War, British power in the colonies was at an all-time low. That was until a ragtag band of visionaries, including Winston Churchill and T.E. Lawrence, proposed that the aeroplane, the wonder weapon of the age, could save the empire. Using the radical strategy of air control, the RAF tried to subdue vast swathes of the Middle East, Asia and Africa. Wings of Empire is a compelling account of the colonial air campaigns that saw a generation of young airmen take to the skies to battle against warlords, jihadists and hostile tribes. For the first time ever, this book chronicles the full story of the RAF's most extraordinary conflict.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 532

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Margaret

First published 2015

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Barry Renfrew, 2015

The right of Barry Renfrew to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 6689 4

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Prologue – Police Bombing

1 Small Wars

2 The Cinderella Service

3 Crisis of Empire

4 The Cheapest War in History

5 The Air Service of the Future

6 The Messpot Mess

7 ‘Everybody Middle East is Here’

8 A New Planet

9 Death and Taxes

10 Desert Kingdoms

11 Before Osama bin Laden

12 Desert Purgatory

13 The Elusive Prize

14 The Kabul Miracle

15 A British Air Service

16 Boom’s Swansong

17 Swift Agents of Government

18 Battle for the Raj

19 ‘What a Mess We Have Made’

20 Bombing for Police Purposes

21 The Last of the Gentlemen’s Wars

22 Legacy

Notes

Bibliography

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I chanced on the subject of Air Control while researching British colonial campaigns during the interwar period for another book. Little has been written about the subject despite the scale of the operations and the elaborate theories that underlay them. My efforts to find out more led to the writing of this narrative history. I benefited greatly from the studies of Charles Townshend, David Omissi and R.A. Beaumont.

The book is based on research at a number of museums and libraries, including the Royal Air Force Museum, the Imperial War Museum, the National Army Museum, and the National Archives at Kew. My thanks to the many remarkable and dedicated people who work at all of these fine places.

A small group of friends played a much bigger role than they probably realised in getting the book aloft with their unfailing help and encouragement. They include Jim Donna, Mike McHenry, Mark Shields, Bill Cranston, Donald Somerville and Wendell Hollis. I hope they will not be disappointed by the result.

I owe a special debt to Field Marshal Sir John Chapple. He has selflessly given of his time, experience and knowledge to inspire and assist people around the world in the study of military history.

My thanks to Michael Leventhal at History Press for taking on the book. Andrew Latimer and Lauren Newby did an excellent job of handling the manuscript.

And above all my thanks to Margaret, who inspired all that is good in these pages.

PROLOGUE – POLICE BOMBING

A solitary aeroplane with a 19-year-old English pilot at the controls raced down a crude runway hacked out of the Sudanese desert in the spring of 1916 as the first red flush of dawn peeled the darkness from the land. Lieutenant John Slessor flew west over the empty wastes, buffeted by low clouds and the desert wind. He wasn’t sure how long he had been flying when he spotted a black smudge in the distance. As Slessor nosed lower, what at first looked like shadows cast by the clouds were transformed into a spectacle from the Crusades.

An army of Muslim horsemen arrayed in long, serried ranks stood in the desert below. Sunlight glinted on the riders’ steel helmets, gleaming breastplates and the tips of their lances; the wind ruffled their white robes; and green and black war flags emblazoned with verses from the Koran fluttered over their heads. It reminded Slessor of the toy soldiers he had played with as a child. For the rest of his life he never forgot the tragic beauty of that doomed army.

Few, if any, of the horsemen had seen an aeroplane before; some pointed and shouted in panic or astonishment, while others stared mutely as it roared over them. For a moment, Slessor was convinced he must seem like a winged god soaring across the sky. Shaking the distracting conceit from his mind, the young aviator began dropping bombs into the heart of the formation. Each blast tore gaping holes in the packed ranks of men and animals. Within minutes the army fractured into a terrified mob as thousands of men and animals bolted in every direction. Although barely noticed by a world transfixed by the titanic battles of the First World War, the defeat of a native army by a single aeroplane was the start of a revolution in British colonial warfare.

Aircraft were only added at the last minute when an expeditionary force was sent in 1916 against the Dervish sultanate of Darfur after it challenged British control of the Sudan. Such a thing had not been done before in British colonial warfare, but a senior official thought that it would terrify natives who had never seen an aeroplane.

Ground operations were already under way in the Sudan when the Royal Flying Corps’ (RFC) 17 Squadron in Egypt received an order on 29 March to provide a flight of four BE2c aircraft. The little wood and canvas planes were far too flimsy to fly the hundreds of miles to Darfur. Each machine had to be dismantled and packed in wooden crates to be transported by ship and then train. Along with them went a little contingent of nine officers and fifty-six men.1

An airbase was built just inside Darfur at El Hilla, with an advance landing strip 50 miles further west at Abiad Wells. The landing strips were just bare earth cleared of rocks and shrub by gangs of Sudanese labourers with wooden tools and their hands. The only shelter against the sun and desert winds, which could warp or crack the planes’ wooden frames if left in the open for even a few hours, were two RFC canvas hangars and a marquee borrowed from the army.

Each tent had just enough space to house a single plane. Teams of mechanics and fitters worked for up to twelve hours at a time in the gloomy, stifling interiors. Poison was smeared on the canvas walls to keep out ants that could devour every part of an aeroplane except the engines and other metal components.

The 40 tons of fuel, weapons and spare parts needed for two weeks of operations had to be taken by camel over the last 100 miles to the airstrip at El Hilla. It took twenty-eight camels to transport the parts that made up each of the canvas hangars, and most collapsed and died after just a day or two.

At dawn on 11 May the first two planes, flown by Lieutenants F. Bellamy and Slessor, touched down at El Hilla. Watching Sudanese soldiers were awed. A British officer wrote in his diary:

For the first time astonished troops saw the beautiful sight of an aeroplane gleaming against a gold sunshine as it turned in a downward circle to land on the prepared stretch of ground. The ship of the air brought down the house. ‘By God! Our General is very clever,’ murmured the marvelling soldiery.2

The pilots had little time to appreciate such veneration; flying over the western Sudan was difficult and dangerous. Severe turbulence buffeted the frail aircraft and sandstorms, towering thousands of feet, appeared without warning and easily outraced the lumbering planes. Navigation over the desert was mostly guesswork: there were no reliable maps, and few hills or other natural features on the dun-hued landscape to steer by. Huge arrows of white calico cloth, 25ft long and 3ft wide, were positioned every 30 miles across the desert to stop crews going off course.

Slessor was guided on one flight by the sergeant major of a native camel unit, a hulking 6ft 4in Sudanese. The man had never seen an aeroplane before, but he climbed calmly into the front cockpit and unerringly guided Slessor over the empty desert with confident sweeps of his great hand.3

The air contingent made a dramatic debut in the campaign on 12 May when a plane flew over El Fasher, the capital of Darfur, roaring above the palace of Sultan Ali Dinar. In a gesture from an older, courtly era of warfare, the pilot tossed down a challenge demanding the sultan’s surrender. In elaborate Arabic, it said that Ali Dinar did not possess ‘the character, the knowledge, nor any other quality of an enlightened ruler’.4 Ali Dinar’s reply was tossed into the British camp a few nights later. He derided the aeroplane as a ‘disguised horseman’, and said the commander of the English force would be tortured ‘in the worst possible manner’ and his severed head displayed in El Fasher’s public market ‘as an example to people of understanding’.5

Such exploits were novel and exhilarating, but the army saw them as mere antics and the flyers were relegated to scouting and conveying messages as the soldiers set out to win the war with tactics that had barely changed in a century. The force of 3,000 mostly Sudanese and Egyptian infantry advanced in pageant-like splendour across the desert in a huge, bristling square of men and weapons. The flags of the battalions flapped in the desert breeze, and the sun glanced off the steel cannons and the long lines of bayonet-tipped rifles, as bugle calls and the bark of drums pierced the air. Marching lines of infantry formed the living walls of the square, their ranks shielding the horse-drawn guns, supply wagons and more than 2,000 pack camels in the centre. Cavalry and mounted scouts reconnoitred ahead and guarded the flanks. At the end of each day, the formation was transformed into the lines of a camp simply by halting.

British scouts on 22 May found a force of 3,000 Dervish warriors about 13 miles from El Fasher. Poor weather had grounded the air contingent and it would play no part in what was to come. A company of camel troops went forward to goad the Dervishes into abandoning their positions and attacking. What followed was more like a ritual than a battle, a one-sided choreographed slaughter at which British armies had become adept in colonial campaigns. Screaming warriors, most on foot and armed only with swords and spears, lunged across the intervening stretch of sand, a wave of half-naked bodies in a frantic race to reach the distant lines of riflemen, machine guns and cannons. There must have been some apprehension in the British ranks – Dervish spearmen had done the seemingly impossible before and broken a British square.

The Dervishes were still hundreds of yards away when the British opened fire with artillery, machine guns and rifle volleys. For forty minutes the warriors hurled themselves at the square, trying to force their way through a wall of exploding shells and bullets with their bodies. Several times they were halted by the withering fire, only to regroup and surge forward again.

The charging men, their lungs and hearts pounding with fear, strain and desperation, had to leap over the shattered and bleeding bodies of dead and wounded companions. A few got to within 10 yards of the British lines before being cut down, and then the Dervishes’ determination snapped and the survivors turned and fled. More than 1,000 dead and wounded littered the ground, their blood-splattered white and brown robes fluttering in the morning breeze. Among the mangled corpses were many boy soldiers.

Ali Dinar was waiting for the British outside El Fasher the following day with 2,000 cavalry who were the cream of his army. The airmen were desperate to play a role in the final battle and demonstrate the potential of air power. Flying conditions were still bad, but a single plane piloted by Slessor got into the sky. He spotted the Dervish cavalry and attacked while the British ground force was still miles away. His BE2c had a single machine gun and could only carry four 20lb bombs in the desert conditions, but it was a formidable arsenal against men armed mostly with swords. He zoomed over the horsemen, releasing on each pass a single bomb that bowled over clumps of riders and animals.

With one bomb left, Slessor glimpsed a figure on a white camel ringed by guards in the centre of the Dervish Army. He realised it must be Ali Dinar, and released the last bomb. Its blast tore the camel to bits, hurling the sultan to the ground and killing two of his guards. Ali Dinar was led away by his servants as his army disintegrated and fled. Slessor had little time to watch the rout: a bullet smashed through the plane’s canvas side, slamming into his thigh. Battling to fly back to the airstrip through a sandstorm and the searing pain of the wound, Slessor had no time to think about the momentous implications of what he had just done.

⋆⋆⋆

Histories of the British armed forces invariably treat the decades between 1918 and 1939 as little more than a footnote between the two world wars. Accounts of the Royal Air Force, in particular, skip over the interwar years, fast-forwarding to the rapid expansion of the later 1930s to meet the threat of Nazi Germany and the development of iconic aircraft such as the Spitfire and Hurricane.

Almost forgotten is how the RAF in the interwar years waged one of the most extraordinary conflicts in the history of the British Empire. With British power crumbling in the wake of the First World War, a ragtag band of visionaries and aviators set out to show that the aeroplane, the wonder weapon of the age, would save the empire. A generation of young airmen in primitive wood and canvas biplanes fought a series of campaigns over Iraq, Afghanistan, Somalia and other battlefields where, almost a century later, the West is still locked in a battle for power and beliefs.

The airmen derided the army and navy as redundant, able only to crawl across the face of the earth like slugs. Air power alone, with its speed, force and flexibility, they argued, could hold down vast stretches of territory and the warlike people who inhabited them. This doctrine of replacing ground forces with aircraft was called Air Control, or more tellingly, ‘police bombing’, and would be used to control huge swathes of the Middle East, Asia and Africa. Aircraft and bombing were employed for everything from frontier wars to enforcing tax collections. Air power became so crucial that the bomber, rather than the battleship, was hailed by some as the true symbol of British imperial power.

Air Control was pivotal in saving the newly-formed RAF from being disbanded after the First World War. Prime ministers, Cabinet ministers and civil servants wanted to scrap the air force to save money. A population eager for peace believed the force served no useful purpose, and was even a threat to stability; and the navy and army were determined to break up what they saw as a bunch of uncouth upstarts and regain their duopoly of military aviation.

The air force lived under ‘suspended sentence’ of death for years, one minister said.6 If the RAF had not proved its worth over the Khyber Pass and the deserts of Iraq in the 1920s, its opponents at home might have succeeded in destroying it. Britain’s fate in the Second World War might have been very different if the country had lacked a strong air force in 1940.

Colonial conflicts preoccupied the British military during the interwar era to an extent not understood today because we are blinkered by the knowledge of what was to come in the Second World War. There was barely a year between 1919 and 1939 when British forces were not locked in a colonial campaign somewhere in the empire. These wars were far from negligible, despite being dismissed as so-called ‘small wars’. The military’s losses in these campaigns exceeded the casualties their modern counterparts have suffered in Iraq and Afghanistan – a single Indian frontier campaign in the late 1930s saw the army sustain 312 dead and 893 wounded in a few months, a toll rivalling British losses in a decade of fighting in Afghanistan in this century.7

Until the early 1930s, many in Britain’s military establishment were more concerned about the threat posed by tribes of the North-West Frontier of India than the possibility of another world war. In these years, the RAF focused on strategies to suppress ‘primitive’ tribesmen rather than future bomber offensives in Europe. These colonial air campaigns helped prop up the British Empire in its twilight years. They also inaugurated a new type of warfare in which poorly armed, but skilled and zealous opponents in some of the most remote places on earth were fought at a distance with the latest Western military technology: the use of drones and satellites to kill militants in such places as Afghanistan and Yemen, some of them the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of those the RAF bombed, is the descendant of the campaigns of almost a century ago.

These colonial campaigns were formative in shaping the young RAF. This first generation of career airmen formed the bedrock on which the force was built, and colonial service did much to shape its enduring professionalism, fighting spirit and dedication. Many of the outstanding British air commanders of the Second World War, including Harris, Dowding, Portal and Slessor, were pivotal figures in the Air Control saga, and many of their key subordinates learned their trade on colonial service. It is quite remarkable how so many of the young men who figure in these pages as pilots and junior commanders rose to the highest ranks during and after the Second World War.

Air Control was based on the premise that aircraft would end small wars and unrest by keeping constant watch, like a giant eye, over the wilder parts of the empire, instantly detecting and crushing any sign of unrest or rebellion. It was claimed that even the fiercest tribe or warlord would submit to a weapon that struck from the heavens like divine wrath, and against which they would be defenceless.

Employing technology to win wars and master hostile territory was hardly new. Superior military technology and organisation always played a key role in the triumph of Western colonialism; the aeroplane was the latest step in a progression that included the repeating rifle, the machine gun and the gunboat. The architects of Air Control tried to go much further than mere bombing, however, and some of the keenest minds in the RAF spent much of the interwar era trying to develop a complex strategy of colonial control, drawing on everything from psychology to economics.

More beguilingly for British officials and taxpayers, air power was cheap; air policing promised success for a fraction of the cost in money and British lives consumed every year by colonial land campaigns. Unlike the extravagantly expensive warplanes of the jet age, military aircraft in the 1920s were built from wood, canvas and wire, and cost a few hundred pounds. The RAF received just a tenth of the military budget in the 1920s, but its contribution to imperial firepower was out of all proportion to its paltry share of defence spending. Historian R.A. Beaumont calculated that the RAF could carry out colonial operations for just 5 per cent of what it cost the army to do the same work.8

Advocates said colonial air power also meant ‘control without occupation’, reducing the need for expensive garrisons.9 Air Control was touted as the modern equivalent of alchemy, but instead of turning lead into gold it would increase British military power while drastically slashing its costs. Inspired by this lethal bargain, Britain, more than any other Western colonial power, was to rely on the bomber as a means of imperial control.

Ultimately, Air Control depended on bombing largely defenceless people and villages with the most destructive and terrifying weapon of the age. Thousands of men, women and children were killed and injured in British colonial operations between 1919 and 1939. Further immense suffering was inflicted by the destruction of the homes, farms, crops, orchards, irrigation systems and herds that these primitive societies depended on for their meagre survival. Inspired by the possibilities of scientific warfare, some in the RAF advocated the use of poison gas, early forms of napalm and other innovations to subdue some of the most primitive people in the world.

The air force and its supporters insisted that Air Control was humane, claiming that it saved lives because it prevented or shortened wars and rebellions, and the use of lethal force was limited. Above all, the RAF argued that Air Control worked because it broke opponents’ morale rather than their bodies; the moral effect, they said, was out of all proportion to the physical damage. The airmen liked to compare themselves to the kindly neighbourhood bobby. But George Orwell, who had been a colonial police officer, used the Stalinist purges of the 1930s and Air Control in one of his most famous essays as examples of how language was used to distort or conceal truth. ‘Defenceless villages are bombarded from the air, the inhabitants driven out into the countryside, the cattle machine-gunned, the huts set on fire with incendiary bullets: this is called pacification,’ he wrote.10

There is no way to calculate the casualty toll from two decades of bombing: most of the raids were in inaccessible areas on backward, mostly illiterate communities that had no way of compiling such figures. While there is no overall figure for the number of bombs dropped in colonial policing operations either, it far exceeded the 8,000 tons that British aircraft dropped during the entire course of the First World War, and matched the level of bombing witnessed in the early stages of the Second World War.11

The scale and intensity of colonial bombing steadily increased during the interwar era as planes and technology improved. The 20 tons of bombs dropped in a two-day 1921 operation in Kurdish areas of northern Iraq was a major attack by the early standards of Air Control.12 By the summer of 1930, a fairly routine operation against a handful of villages on the North-West Frontier of India saw the use of 23,826 bombs, weighing a total of 583 tons, 80,853 incendiaries and millions of machine gun bullets.13 By comparison, German bombers and airships dropped some 269 tons of bombs on Britain during the entire course of the First World War.14

Some senior British military commanders and government officials anguished over the human cost of the bombing raids, but air power seemed a panacea for the empire’s ills, and no one was willing to abandon it. Instead, the military and successive governments attempted to conceal the extent of the bombing. Air force and other government files from the interwar period are filled with memos warning that details of raids must be played down or omitted; colonial squadrons were constantly instructed to strip unsettling details from any reports that might be seen by the public. Government ministers were especially anxious to remove anything on the killing of farm animals or wildlife for fear of offending a British public that could be far more sentimental about animals than natives.

Air Control was more than a monotonous chronicle of destruction and heavy-handed colonial control. The RAF protected peaceful tribes and villages from hostile neighbours, and in many areas imposed a rough form of law and order. It defeated an army of Wahabi fanatics decades before the world had heard of Osama bin Laden and it reduced British casualties. But Air Control never came close to achieving the predictions of its architects that it would end all resistance to British rule and usher in a golden age of peace and prosperity across the empire.

Its greatest success was enabling Britain to retain control of Iraq and other parts of the Middle East in the 1920s; it was the only time in history that an air force commanded the defence and policing of large territories. Air Control did less well in the 1930s as opponents, particularly the Pathan tribes of north-west India and better-trained Arab forces, lost their fear of air attack and found many, often brilliantly simple ways to counter the British technological advantage. Whether Air Control could have delayed the end of British imperial rule, as some hoped, is moot; the deluge of the Second World War swept away Western colonialism.

Air Control reinforced the RAF’s belief that air power alone, above all bombing, would win wars. It is possible to see the colonial campaigns as a precursor of the attempt to bomb Nazi Germany into submission; both hinged on the notion of destroying an opponent‘s morale and economy. The RAF’s colonial experience reinforced its disinclination to work closely with the other services, and it took several years to develop effective ground support methods to aid the army during the Second World War. In 1939 the RAF had very few planes and pilots suited for close support operations, despite twenty years of ostensibly working with the army on colonial campaigns.

⋆⋆⋆

This book is not an attack on the men who tried to rule the empire from the sky. Air crews could be happy or heedless killers, who talked about machine-gunning a village as nonchalantly as they recounted shooting a buck or a bird on a hunting trip. They were also mostly admirable, honourable and idealistic young men, among the best of their generation, who believed they were serving their country, the greater good and even those they bombed. The use of weapons ranging from bombs to incendiary devices to chastise primitive people in the name of civilisation, however, is not a comfortable subject. Modern readers are likely to cringe at the prejudice and callousness that imbued the empire’s rulers.

Many airmen, soldiers and colonial administrators argued with complete sincerity that people regarded as savages could only be subdued with savage methods. Such attitudes were as much a part of the RAF’s armoury as the bombs slung under the wings of its aircraft; indeed, Air Control would have been inconceivable without such assumptions. At the same time, Britain and other Western powers saw no contradiction in insisting that it would be barbaric to bomb their own populations. In the later 1930s, the British Government led an international campaign for a global ban on bombing – except in its own colonies.

Military history tends to be written from the standpoint of one side, but any account of the RAF’s colonial campaigns is unavoidably skewed. The voices of the people who lived under the shadow of Air Control were almost never recorded. The few snippets that exist come mostly from British files and the memoirs of airmen, where the natives are usually portrayed as amiable ruffians who regarded the bombing of their villages as a fair price for their own naughty escapades. Air Control is not always a comfortable or uplifting saga, but it is a vital part of British military and colonial history, not least for the insights it provides into the conflicts of the early twenty-first century.

1

SMALL WARS

The British Empire reached its zenith after the First World War with the acquisition of vast swathes of the Middle East and Africa from the wreckage of the Ottoman and German empires. Lord Curzon, one of the grandest of the empire’s proconsuls, caught the pride and assurance of the moment by declaring:

The British flag never flew over more powerful or united an Empire than now; Britons never had better cause to look the world in the face; never did our voice count for more in the councils of the nations, or in determining the future destinies of mankind.1

It seemed that the empire would last for ever. Virtually no one saw that the war which had enlarged this vast realm had also unleashed or accelerated the political and economic forces that would tear it down in just a few decades.

The British preferred to forget or play down that the empire had been conquered, and that large parts of it were held by force rather than the gratitude of their subjects. Garrisoning the empire was a staggering global commitment; British forces had to watch over almost a quarter of the world’s land mass and hundreds of millions of people. Now there was a string of former Ottoman and German territories to be pacified and guarded.

People in Britain, while proud of the empire, wanted the government to improve their living standards rather than spend money on distant colonies. There was considerable grumbling about the costs of some of the newly acquired tracts of desert in the Middle East. ‘Mesopotamia and “Mess-up-at-home-here”’ was a popular anti-government slogan in the early post-war years.2

Winston Churchill, the new secretary of state for war, was faced with the twin challenges of drastically slashing the armed forces and finding more troops to garrison the expanded empire. He summed up the dilemma when he told the House of Commons in December 1919:

Odd as it may seem on the morrow of unheard-of-victories, we have all those dependencies and possessions in our hands which existed before the war, and in addition, we have large promises of new responsibilities to be placed upon us.3

Prime Minister David Lloyd George had given Churchill oversight of the newly formed RAF as well as the army after eliminating the post of air minister. (There was no Ministry of Defence at the time; the three armed services came under their own ministries.) There were suggestions at the time that Lloyd George wanted to disband the RAF and included it in Churchill’s portfolio as a first step to scrapping the service. The air force’s future appeared highly doubtful. Many people in Britain questioned why the country needed an air force after winning what was proclaimed as the war to end all wars, and there were loud calls to get rid of the service. The army and navy, in particular, were determined to destroy a rival that threatened their centuries-old control of military affairs. It seemed to many that the RAF would not last another year. ‘Its chances of survival around its first anniversary in the spring of 1919 were minimal,’ recalled Maurice Dean, a senior official at the Air Ministry. ‘… In the early years the Royal Air Force was miniscule, a breeze could have blown it away and nearly did so on several occasions.’4

The air force was a rich target for a government and populace eager to drastically slash military spending after the world war. The Royal Flying Corps (RFC), formed in 1912 as the army’s aviation wing, had just a few dozen planes when war erupted in 1914. Aviation and warfare transformed each other over the next four bloody years, and by the end of the conflict Britain had the world’s largest air force with 22,000 planes, 263 squadrons and 290,000 men. Air power’s importance was recognised when the Royal Air Force was created on 1 April 1918 by combining the army and navy air wings to form an independent service. Peace changed everything. The RAF was singled out for some of the deepest cuts after the war; its ranks were reduced by 90 per cent, dozens of airbases were closed and the number of squadrons dwindled to just twenty-four by early 1920.

Whatever Lloyd George or others thought, Churchill had no intention of abolishing a service that appealed to his enthusiasm for innovation, daring and romance, and might also solve the conundrum of policing the expanded empire while cutting military costs. He favoured keeping the territories that had been seized during the war, particularly the Middle East acquisitions, but knew that it had to be at a price which the country could afford and public opinion would stomach. Within weeks of taking charge at the War Office, Churchill was considering how to save the RAF by using it to police the new territories.

Sir Frederick Sykes, head of the RAF after the war, wrote the first formal proposal on a colonial role for the air force. Aircraft, with their speed, striking power and low cost, were ideal for imperial police work, he wrote, and would be of particular value in the Middle East. But Churchill was not impressed by Sykes or his proposal for a peacetime air force of 150 squadrons. The politician knew that such grandiose plans would never be accepted in the political climate of the day. He wanted a man who could run the RAF and help control the world’s largest empire on a shoestring; his search for a candidate led him to a complex, prickly, former army officer named Hugh Trenchard.

Trenchard was a towering figure in every sense. He stood 6ft 3in with piercing blue eyes and a formidable moustache that announced his fearsome personality. He was nicknamed ‘Boom’ because of the power of his voice when animated or angry, which he often was. Trenchard was a masterly administrator; an autocratic, if inspired, manager of men rather than a dashing leader; a tireless worker with a superb grasp of detail; a brilliant politician, with a deft sense of the public mood and a ferocious antagonist. He possessed the necessary combination of vision, practical skill and belligerence needed to save the infant air force from being throttled by the older armed services, penny-pinching civil servants and indifferent politicians in the early years after the First World War.

Trenchard has been celebrated as the father of the RAF ever since. His many admirers saw him as a giant towering over pygmy rivals in the military and political establishments. Some of his most ardent supporters were not obvious friends of authority or the professional military. T.E. Lawrence, whose adventures in Arabia made him a far bigger legend than Trenchard, wrote, ‘Trenchard spells out confidence in the RAF … He knows; and by virtue of this pole-star of knowledge he steers through all the ingenuity and cleverness and hesitations of the little men who help or hinder him.’5 The professorial author of the RAF’s First World War history described Trenchard in similarly Olympian terms, ‘The power which Nature made his own, and which attends him like his shadow, is the power given him by his single-ness [sic] of purpose and faith in the men whom he commands.’6

Trenchard could inspire loathing as well as adulation, but did not seem to care which, as long as he got his way. He was a man of strong emotions, aggressive and quick-tempered, who frequently and needlessly personalised disagreements over official issues. Trenchard’s detractors, including more than a few in the air force, saw him as domineering, opinionated, divisive and self-righteous. Even admirers, who downplayed his flaws as the quirks of an endearing ogre, admitted he excelled at needlessly provoking people. Weary friends and aides said that Trenchard believed he must be doing something right if everyone disagreed with him. And yet even many of those who disliked him conceded the importance of the man’s achievements.

Born in 1873, there was little in Trenchard’s early life to suggest the commanding figure of later years. Trenchard’s father was a struggling country lawyer in Somerset, and his upbringing had the feel of penny-pinching Dickensian shabbiness. Young Hugh was an unexceptional child who was happiest roaming the countryside around the family’s rural home. He disliked school, his handwriting was indecipherable and he enraged teachers with his atrocious spelling. Part of the later Trenchard legend was his inability to express his ideas clearly. To get around this, Trenchard would toss out rambling, disconnected thoughts to aides he called his ‘English merchants’, who would then rewrite them until their master announced they had got it right. ‘I can’t write what I mean, I can’t say what I mean,’ he once told an aide, ‘but I expect you to know what I mean!’7

His parents’ plan for a career as a navy officer had to be abandoned when Trenchard failed the entrance exam. It was decided to put the boy into the army if he could get through the less demanding entry tests. At the age of 13 Trenchard was sent to a crammer, an educational battery farm designed to force youths through entrance exams without necessarily imparting any learning. His father’s legal practice collapsed, meanwhile, and the family was left bankrupt. Trenchard was to become good at skimping, something that would endear him later to government cost cutters.

Frugality did not boost his academic abilities, however, and Trenchard twice failed the test for the regular army. The British establishment, with plenty of sons and few suitable careers for gentlemen, had other ways of getting around obstacles like mere entrance exams. Trenchard scraped his way through the exam for the militia, or part-time army, which was a backdoor into the regular army for the dullest scholars. It was enough to get the 20-year-old Trenchard a commission with the Royal Scots Fusiliers, who were then in India.

Soldiering, with its practical, outdoors life, suited Trenchard. Contemporaries remembered him as a good, if unexceptional, platoon officer, although he was awkward and uncomfortable with the social routine that was an important part of the peacetime army; he was dubbed ‘the camel’ in the officers’ mess because he rarely drank anything stronger than water. Even as a young man Trenchard was noted for being prickly, and in the army he did not hide his contempt for anyone he disliked, including superior officers. He occupied most of his spare time running the regimental polo team, with freelance horse dealing to supplement his pay because, unlike many officers, he did not have independent means. Nobody seems to have thought that he was destined for great things.

Trenchard’s lacklustre career picked up with the outbreak of the Boer War. He fought in the mounted infantry until he was shot in the left lung attacking a Boer post, made a spectacular recovery, and was promoted to major and given a job shaking up units that had not done well on the battlefield.

Whether because he had developed a taste for active service or for Africa, Trenchard obtained a post in 1903 as deputy commander of the Southern Nigeria Regiment. Britain’s African colonies were mostly garrisoned by black troops led by regular British officers on temporary contracts. Such postings were popular because they were a chance for active soldiering and paid well. They attracted some of the best and some of the least savoury characters in the army. Trenchard walked into the mess at breakfast shortly after his arrival to find the officers lounging about unshaved and in pyjamas; most of the conversation was about drink, sex with native women and gambling. It was an appalling revelation for a man who was a natural puritan. Trenchard promptly banned drunkenness, illicit sex and gambling, and officers who failed to meet his strict sense of decorum were sent home.

Britain was still imposing its control on the more remote regions of its West African possessions, and colonial forces freely employed harsh tactics. Trenchard led columns deep into the bush on sweeps lasting weeks. The formations trudged through the jungle for weeks in search of elusive opponents, enduring searing heat, intense humidity and hungry insects that wracked men’s bodies with infected bites.

Initially, Trenchard employed the traditional, heavy-handed tactics of burning villages and whipping captured natives. Questions were asked in Parliament following press reports that a column led by Trenchard had burned six villages. A government spokesman said such tactics were necessary to end lawlessness and open ‘backward’ areas to trade. As he learned more about the people and the country, Trenchard later claimed he used different methods, offering the natives a choice between punishment or peacefully accepting British rule.

Trenchard returned home in 1910. Africa had been exciting, but had not done much for his career. Now 37, he was just another nondescript major facing an impoverished retirement. Attempts to get postings with colonial cavalry units in Australia, New Zealand and South Africa were unsuccessful, as was an application to the Macedonian Gendarmerie. And then in 1912 a fellow officer breezily suggested that Trenchard learn to fly with the army’s new aviation wing. ‘Come and see men like ants crawling,’ was the offhand suggestion.8

It was a startling idea; flying was for the young and unconventional with a good chance of death or crippling injuries in the notoriously unstable and dangerous machines of the day. Trenchard was 39, and the cut-off age for entry to the army’s tiny aviation wing was 40. He gave himself a week to earn the flying licence required for admission to the RFC. The qualifying exam was mainly a question of staying alive – Trenchard’s test consisted of taking off solo, climbing to 1,000ft, flying a figure of eight over the airfield and landing.9

In view of his age and experience, the newly qualified pilot was given a staff position rather than an active flying role. The coming of the First World War saw Trenchard rise rapidly, and he was commanding the RFC on the Western Front by 1915 with the rank of major general. He was still an army man, however, and shared the dogmatic belief of the General Staff that victory would only be achieved by breaking the Germans with massive ground attacks on the Western Front. In the same spirit, Trenchard hurled his crews at the enemy despite inadequate resources, lack of training and heavy losses in the early years. Critics, including some of his officers, accused him of throwing away lives; he replied that casualties were the price of success.

It is the supreme irony of the early history of the RAF that the man who ensured its survival had vehemently opposed its creation. Trenchard was highly critical of the decision to form an independent air force; he believed the air squadrons should be part of the army like the artillery or the engineers. Despite his opposition, Trenchard was picked to head the new service, but quickly fell out with Lord Rothermere, the bombastic press baron who was air minister, and resigned. Rothermere later said sourly of his former subordinate, ‘He was a man who tried to strangle the infant [the RAF] at birth though he got credit for the grown man.’10

After several weeks mostly spent brooding on a London park bench, Trenchard was given command of an independent bomber force to attack Germany, a role he took on with his usual drive. He left France a few days after the war ended, sure that his military career was behind him until he was summoned to see Churchill. The two men met in early February 1919 and talked about the RAF’s future. Impressed by what he heard, Churchill told Trenchard to write a memo on restructuring the service. That evening Trenchard jotted down in 700 words a plan for a barebones air force. His thinking had undergone a total turnabout: he now believed that the aeroplane had transformed warfare, making ground and sea forces largely redundant, and that Britain’s and the empire’s security depended on an independent air force.

No one was thinking about the possibility of another war, however, and Trenchard had to make the RAF indispensable there and then to ensure its survival. The only realistic way was to show that an independent air force could police the empire more effectively and, above all, more cheaply than the older services. The brief plan that Trenchard gave Churchill envisaged a small, robust air force for colonial defence and policing that could also serve as a foundation which could be expanded, if needed, in the future. Although sparse in details, the scheme was the pragmatic, cut-rate approach that Churchill was looking for, and he insisted Trenchard replace Sykes as head of the air force. Churchill was soon telling colleagues that the RAF would transform imperial defence. ‘The first duty of the Royal Air Force,’ he told the House of Commons, ‘is to garrison the British Empire.’11

Taking command of the embattled RAF, Trenchard promptly staked its future on the empire, allocating nineteen of its twenty-four squadrons to colonial stations with just two for home defence, while the remainder were given naval or training roles.

For a century, the British Army had spent much of its time fighting ‘small wars’ across the empire, conflicts which a leading military handbook defined as ‘expeditions against savages and semi-civilized races by disciplined soldiers’ or wars against non-white opponents.12 Most of these wars were never-ending pacification campaigns on the wild fringes of the empire in Asia and Africa, where imperial authority petered out amid the deserts and the mountains with their impenetrable terrain, implacable climates and ferocious inhabitants. Military columns would be sent out when the tribes became too troublesome, to inflict what the army euphemistically termed ‘havoc’, killing tribesmen, destroying villages and burning crops – army veterans sardonically summed it up as ‘butcher and bolt’. Such methods, which were justified on the grounds that ‘savages’ did not respect the rules of war, rarely brought more than a temporary, sullen truce, however, forcing the British to mount endless campaigns.

Most air force leaders in 1919 were ex-army officers who had served on the Indian frontier or in the jungles of Africa, where they experienced the brutal reality of colonial warfare and the maddening difficulty of subduing far weaker opponents. They and others saw that the aeroplane, with its ability to vanquish the obstacles of terrain, climate and even time, could revolutionise colonial warfare. It is not clear who came up with the term ‘Air Control’, but it was widely adopted sometime around 1919, and expressed the RAF’s emerging belief that air power would revolutionise the control of the empire by halting the seemingly endless cycle of small wars.

The army justified its methods by arguing that a short, savage dose of punishment broke the morale of belligerent tribes, and avoided more protracted wars and the casualties that went with them. That reverberated with the RAF, which claimed that aerial bombing worked primarily by ‘moral effect’, breaking an opponent’s will to fight or resist, rather than by inflicting massive damage. ‘The moral effect of bombing stands to the material in a proportion of 20 to 1,’ was one of the cardinal tenets of the young RAF.13

Surely, the airmen said, such methods would be even more effective against ‘backward’ and ‘ignorant’ savages. Nor were there qualms about using bombers, the most advanced and destructive weapon of the day, to suppress ‘backward’ people. The British military had always been more willing to try out new weapons against primitive tribes. Veterans of African wars dryly noted that the army saw the machine gun as an excellent way to stop ‘wild rushes of savages’ while showing ‘a good deal of prejudice’ over its use against white troops.14 Or as Robert Graves, the novelist and poet, archly commented, ‘There had always been a tacit understanding that a different code might be used by European nations against savages who would not appreciate the civilized courtesies of war.’15

Air Control was used interchangeably to refer to both the underlying doctrine and actual operations during the interwar period. It would take several years after 1918 to develop and refine the basic idea of aircraft controlling territory and tribes into a fully-fledged strategy. Aircraft and air war were only a few years old, and while the airmen saw limitless possibilities they still had to learn what was practical.

At first, many British airmen naively or lazily believed that the mere sight of a flying machine would reduce even the most warlike tribes to jabbering wrecks. This was followed by schemes of early aerial surveillance to prevent unrest and, if that did not work, bombing raids to isolate and subdue troublemakers. Some of the more visionary RAF theorists worked on ways to control native societies with a form of collective mind control. But whether it was done with psychological pressure, economic warfare or mass bombing, instilling terror and a sense of helplessness was at the heart of Air Control.

Wing Commander R.A. Chamier, in a 1921 talk entitled ‘The Use of Air Power for Replacing Military Garrisons’, candidly stated:

… the Air Force must, if called upon to administer punishment, do it with all its might and in the proper manner. The attack with bombs and machine guns must be relentless and unremitting and carried on continuously by day and night, on houses, inhabitants, crops and cattle … This sounds brutal, I know, but it must be made brutal to start with.16

Trenchard and the RAF had no doubts that air power could pacify the empire’s lawless fringes for a pittance compared to the huge quantities of men and money the army consumed annually for often imperfect results. ‘Air Control will go far to prevent the occurrence of what for years has been described as a “chronic disease of the British Empire”, in the shape of long drawn-out frontier wars and recurrent punitive expeditions,’ an air theorist wrote.17 Having found a role for the RAF, Trenchard now had to ensure it would meet the challenge.

2

THE CINDERELLA SERVICE

U nlike the navy and the army, the RAF did not have a peacetime establishment or traditions to fall back on after the war. When S.E. Towson enlisted in the force, all of the non-commissioned officers at the training depot were army veterans of the Boer War, and lectures on the air force’s history were extremely short.1 To Trenchard it was an ideal chance to build a visionary service that would transform the empire’s defences.

Trenchard’s vision rested on creating a new type of warrior. He proclaimed that the air was the new dimension of warfare, totally distinct from the land and the sea. It could only be mastered by a new breed of officers who were brainy as well as brawny, able to control the most complex technology, fight wars scientifically and command the heavens. Many of the RAF’s rougher wartime veterans were replaced by better-educated recruits who fitted the new template, although it took time. A 19-year-old Geoffrey Tuttle began his career in 1925 in a squadron where breakfast consisted of pink gins in the pilots’ mess.2

With its need for talent, the air force was willing to overlook humble origins for real ability. Sydney Ubee, a future air vice marshal who served in Iraq and India in the 1930s, worked as a labourer and a car salesman before being accepted as an officer cadet, while Francis Long, a future test pilot and air vice marshal, was a factory apprentice.3 It all lent the service an image of being less rigid, more meritocratic and more in tune with the progressive spirit of the times than the older services. This did not mean the RAF was free of the class divisions and snobbery that were still a hallmark of many parts of British life, and the armed forces in particular; very few air force officers saw a mirror image of themselves in the lower ranks. Still, there was not much room for class barriers in a two-man plane crewed by an officer and an enlisted man over the Khyber Pass or the Iraqi desert.

Trenchard also insisted that the RAF improve its social standing and reputation. Pilots had been idolised as knights of the air during the war, but were also notorious for wild excesses and flouting convention. The service’s official history of the war said aviators should be judged by their courage rather than their manners.4 An element of disrepute dogged the little force after the war. Fairly or not, air force officers had a reputation for being too friendly with other peoples’ wives, not paying their bills or being light-fingered with official funds. ‘We tended to look over our shoulders at the other services and it worried us that it so often seemed to be an officer of the Royal Air Force whose cheque bounced or who was mixed up in a scandal,’ recalled T.C. Traill, yet another future air vice marshal who shot down eight enemy aircraft during the war.5

The country’s powerful upper classes were suspicious of a service filled with officers from humble backgrounds or the colonies; such men did not fit the traditional image of an officer as a man of impeccable breeding and social graces. A government minister complained that ‘the calibre of young [RAF] officers who are taken in now is very low, worse even than many of those who were taken in during the war, and we know what their standard was’.6

Much of the business of government was still done in the salons and country houses of the establishment. Such doors were often closed to the air force in the early post-war years, and its leaders complained of what they called the service’s lack of ‘dining out power’. Trenchard and his senior lieutenants worked tirelessly to charm politicians, society matrons, newspaper editors and other potential backers, but it took years to finally transform the service’s reputation. Tuttle, who would rise to be vice chief of the Air Staff in the 1950s, said it was difficult to get car insurance in the 1920s because insurers lumped RAF officers, actors and Jews together as the worst risks.7

The RAF did not want for recruits, even when it seemed that the force might not survive. Most young men were drawn by the power and romance of the aeroplane, the ultimate symbol of the technological revolution that was transforming the world. Flying had a novelty and glamour in the interwar era that is hard to comprehend in modern times. Aviators were among the leading celebrities of the day along with film stars, royalty and business moguls; anyone associated with aircraft, no matter how humbly, was touched by the magic of flight.

RAF leaders knew that one of the service’s strongest advantages was its image of spearheading the future. An article in the RAF Quarterly declared:

To the ardent youngster who wants to see the world in a novel and romantic guise the Royal Air Force offers far more. This is a mechanical age, an age of ever increasing speed, and an age of rapid scientific development, and where can the rising generation enjoy all these to anything like the same extent as in the Royal Air Force?8

A generation of schoolboys, who had grown up making model aeroplanes and reading about heroic pilots, provided a steady pool of eager recruits. Working-class youths who could not expect to be officers and pilots aspired to be the mechanics and fitters who kept the great machines flying. In the post-war years, the RAF provided excellent technical training at a time when educational opportunities and good jobs for the lower classes were scarce.

Gilbert Smith, who served in India in the 1930s, joined the RAF apprentice system at 16 to learn electrical engineering. The three-year course – with its tri-part program of general education, technical instruction, and military training – was gruelling. Apprentices spent long days in classrooms and workshops, often working late into the evening, but graduates were keenly sought by civilian companies after they left the service.9

Travel was the other great enticement to join the air force in an age when few people could expect to go far from home. RAF recruiting campaigns played up the service’s numerous foreign stations and the opportunity to travel and see the empire. Richard Brooks was an 18-year-old office boy in the mid-1920s when he saw an RAF poster with a painting of a desert oasis and palm trees that brought back all of his boyhood dreams of foreign adventure; he walked into the recruiting office and soon found himself in southern Iraq.10 Religion still had a strong hold on British society, and the RAF’s numerous stations in the Middle East attracted plenty of young men who wanted to see the places they had read about in the Bible as children.11

Even the lowest-ranking airmen could see a lot of the world if they saved their pay and made the best use of leave time overseas. Sydney Sills, a wireless operator in the 1930s, visited the ruins of Babylon and Ur, the palaces of Baghdad, the Taj Mahal, the temples of Rangoon and Singapore’s Tiger Balm Gardens. 12 Spencer Viles, an air gunner in Iraq in the early 1930s, managed to travel across almost the entire country.13

New officers and men learned about the benefits and drawbacks of foreign posts through a service grapevine: Egypt and Malta were seen as the best postings because of the climate and comfortable lifestyle; Singapore and Hong Kong became popular after the RAF established bases in the Far East; but Iraq and Aden had hideous reputations.

Colonial postings were also a chance for officers and enlisted men to taste the privileges and comforts of the empire. For the lower ranks it was a chance to be the masters for once. ‘In those days the Raj was definitely supreme so if you were white you were a top dog,’ recalled Smith, who served in India. ‘Even as AC2 [aircraftman second class] you were still a burra sahib and you had everything done for you because you had batmen, you had waiters, you had bearers.’14

Stanley Eastmead, who served in an RAF armoured car company in Iraq in the mid-1930s, said a firm belief in British superiority over the rest of the human race saturated the ranks. ‘You always had the sort of feeling then that if you were British you were bloody good and the rest of the world, well, they were definitely second-class citizens. That was the attitude we had, we had this instilled into us.’15

All ranks took it as a fact of nature that black people were inferior and must defer to the British rulers. One young officer, G.V. Howard, was furious when he went to a Baghdad nightclub and found Arabs being served alongside British officers and officials. ‘I consider it is damn bad for British prestige,’ he wrote home.16 Howard believed Arab labourers and servants should be kept in their place with a taste of the riding crop, although officers should delegate such tasks. ‘I think it is rather undignified to do it yourself, besides being unpleasant,’ he noted.17 Squadron Leader E. Brewerton, a languid young fighter pilot, had no reservations about dirtying his hands. He and another officer had a disagreement with ‘two dirty Indians’ over the cost of rowing them ashore in Karachi in 1920 during a port call; they tossed one of the boatmen into the water, after which ‘they agreed to take us in for our price’.18

Not everyone who joined the RAF was drawn by dreams of flying or foreign adventures. Some men and boys enlisted for the same reasons or compulsions that had pushed men into the forces for generations: poverty and the lack of work, or the need to find a haven or obscurity for personal reasons. Patriotism, a sense of service and idealism motivated some to enlist, while others joined because they had been too young to serve in the war and did not want to spend their lives wondering what they had missed. More than a few recruits joined because they had nothing better to do.

John Buckley, at the age of 19, faced a choice between the armed forces or a life in the coal mines of his native Wales. He and two friends were given railway tickets to the RAF recruiting office in Liverpool, the start of a journey that within a few months took him to the deserts of Iraq.19