Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

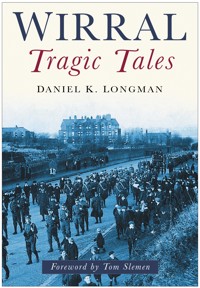

Fresh from his research into the dark side of Wirral's history, in his first book 'Criminal Wirral', Daniel K. Longman has plunged back into a brand new selection of terrible and tragic tales.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 176

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2007

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

WIRRAL

Tragic Tales

For all those who have fallen victim to loss and tragedy

WIRRAL

Tragic Tales

DANIEL K. LONGMAN

Foreword by Tom Slemen

First published in the United Kingdom in 2007 by Sutton Publishing

Reprinted in 2009 by

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Reprinted 2011, 2012

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Daniel K. Longman, 2011, 2013

The right of Daniel K. Longman to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 5332 0

Original typesetting by The History Press

WITH THANKS TO

Christina Sutton

Glynis L.N Preston

Chris High

Tom Slemen

Birkenhead Central Library

Picture credits: Historic photographs courtesy of Ian Boumphrey; modern photographs, author’s collection. Maps courtesy of Birkenhead Central Library.

CONTENTS

Foreword

Introduction

A Deadly Dose

An Unintended Libation

Mersey Fireworks

A Runaway Horse

The Snow Woman

The Exploding Boiler

A Savage Scent

A New Ferry Fire

A Crushing Commute

Mournful Masonry

Rabies

The Tranmere Quarry Tragedy

A Fatal Omnibus

Sand Suffocation

Clothes Combustion

The Tunnel Tot

Observatory Plummet

Munitions Maintenance

Out for the Count

A Woeful Wash

A Municipal Misfortune

A Guilty Porter

The Calamity Cruise

A Hazardous Occupation

An Imprudent Youth

Guillotined

A Harmful Hesitation

The Widow Worriers

The Bebington Showground Disaster

A Dedicated Village

A Brave Mayor

A Devoted Brother

Rifle Respite

A Deep Sleep

Sibling Adversity

Starvation

The Hoylake Special

An Epileptic End

The Lost Boy

A Shunting Tragedy

A Plumber to the Rescue

A Cyclist’s Claim

The New Brighton Blaze

A Lamentable Labour

Animal Cruelty

A Lethal Toy

Overexcited

Mortal Elevation

A Day at the Races

The Dangers of Naptha

Loaded

Undertaken

FOREWORD

Charlie Chaplin, that great observer of the human situation, once remarked that life is a comedy in long-shot and a tragedy in close-up. This also applies to the individual throughout history. In long-shot the individual is just a statistic in a war, a plague, an earthquake, a pogrom, a fire or an accident. Six million Jews were exterminated by the Nazis, and each and every one of them was a person, exactly like you and me, but who were they? We know about a fraction of these people, but for most of us who flip thorugh history books, they shall remain anonymous victims of the Third Reich. The same is true of Titanic disaster, the atom bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and in more recent times the tsunami which killed 230,000 people on 26 December 2004 or the 2,749 people who died in the Twin Towers on that terrible day in September 2001; it’s difficult to imagine death of that magnitude. Each of those people who perished in the towers or jumped to their death was someone’s loved one.

Historians tend to ignore the life of the individual and deal instead with dates and the courses and causes of events. This macroscopic narrative often makes dull reading, and I have always been more intrigued with the lives of individuals and local and international history, rather than 1066 and the family trees of the Tudors and the succession of popes and Roman emperors.

In Wirral Tragic Tales, Daniel Longman has detailed the lives of everyday people who are not kings or queens, dukes or earls, all caught up in tragedy –something that affects us all in one form or another during our lives. In my opinion, this is true history, not some Act of Parliament or signing of a charter. Yes, parliamentary legislation affects people’s lives, but a piece of paper or a world-changing idea is an inanimate and worthless thing unless people –like you and I –act upon that idea or enforce what was written on say, the Magna Carta. In this book there are fiftytwo fascinating accounts of individuals falling victim to the circumstantial force of tragedy, and the stories range from the gruesome decapitation of a man by hydraulic machinery in 1899 to the tragic death of a woman whose garment burst into flames after accidentally coming into contact with the fire of the kitchen boiler. I have read every story in this book, and I applaud Daniel Longman for the sheer variety of the settings of these personal tragedies, but one story in particular, entitled ‘Starvation’ really touched my heart, and the tragic account made me wonder why there was never a revolution in Britain. I shall leave it to the reader to peruse that story in order to see where I’m coming from.

Tom Slemen

INTRODUCTION

What is a tragedy? There are a number of definitions, each with their own individual points to consider, but I’m sure that you will have your own understanding. There is the devastating loss of a family member, which as you read these words is affecting millions of people worldwide. This, the most common form of tragedy, is one that I’m sure you have experienced at least once in your lifetime. Such losses are private calamities, which become public knowledge only in the form of small black and white obituaries in local, and soon discarded, newspapers. Nevertheless, the disaster looms large for the relatives and friends of the dearly departed.

Then there are those collective disasters which tugs at the heartstrings of an entire town or city. The washout that was New Orleans in 2005 is a clear example of how this sort of tragedy can cause utter carnage for many. The effect of hurricane Katrina that year was most cataclysmic and long-lasting. The storm, which was one of the costliest hurricanes as well as one of the most deadly natural disasters in US history, brought heartache and sadness to many.

On a larger, and thankfully rarer scale, let’s not forget the upheavals that cause chaos to whole countries, continents, and sometimes even the world. Wars raging across the whole of Europe, such as those unforgettable days of the early and midtwentieth century caused misery for millions. The First World War alone created graves for an estimated eight million men, women and children. The worst tragedies are often man-made.

The human race has always had to cope with disaster. The people of Pompeii were literally burnt into the history books in 79 ad when the giant volcano Mount Vesuvius gushed forth layer upon layer of molten lava, bringing with it instant death. The Black Death of the fourteenth century brought pain and suffering in Britain from coast to coast. With a mortality rate of 30–75 per cent, the most common form of the disease, the bubonic plague, caused symptoms such as enlarged and inflamed lymph nodes, unbearable headaches, relentless nausea, incessantly aching joints, a high fever and repeated vomiting. Death was a happy release.

On 2 September 1666 the Great Fire of London swept across our nation’s capital bringing destruction and devastation to many of its inhabitants. Eighty-seven churches were destroyed along with approximately 13,000 houses, the majority of which were built of inflammable timber and thatch. That disaster was brought about by the careless actions of a single baker.

Who could forget the Belfast-built vessel whose name today is etched into the consciousness of modern mankind? The Titanic, that colossal luxury liner which set off on its first and last ill-fated voyage in the month of April 1912. She became an overnight sensation, but for all the wrong reasons. That night over 1,000 passengers went down into the icy waters of the Atlantic and their deaths became the stuff of legends. The crew on board the Titanic are well-remembered for carrying out the Birkenhead Drill; ‘Women and Children first!’ This famous order was first carried out aboard HMS Birkenhead in the year 1852, when the 1,400-ton paddle-steamer became hopelessly impaled on an uncharted rock off the coast of South Africa. It was reported that of the 643 people on board the Birkenhead, only 193 were saved. Those who perished either drowned or were eaten by the great white sharks that are known to inhabit those savage waters. Because of the bravery and selfless sacrifice of the men on board all seven women and thirteen children were rowed away from the doomed wooden wreck to safety. I have not included this tale of gallantry in this book, since to condense an account of such heroism into a mere thousand words or so, would fail to do justice to those admirable men.

Indeed, it is often said that the worst situations bring out the best in people. While researching this book I have found an exceptionally high number of cases that support this claim. A prime example of such heroism took place in the year 1908, when four-year-old Henry Wilson bravely reached out to save his baby sister from drowning in Victoria Park, yet another was the valiant effort of Jabez Hughes who risked severe scalding in his attempt to rescue poor Ivy Williams at her house in Livingstone Street in 1913.

Of course these acts took place decades ago in a time that the majority of us never saw. However, they show us that a real sense of camaraderie and community spirit lies at the heart of society.

This was clearly demonstrated during the atrocities of 7 July 2005, when a series of coordinated bomb blasts struck London’s public transport system during the morning rush hour. Fifty-two people were murdered in the attacks; the four terrorists known to have been involved also died, and about 700 innocent people were injured. This horrific crime brought people together in a united front, each helping those in need, whether they were stranger or friend. It is such acts of modern-day compassion that echo those of the times of Titanic and Birkenhead, and which will be remembered for generations to come.

Of course, such huge losses of life should be remembered, but lest we forget the local citizens that perished tragically, rescued valiantly, or witnessed some of the most amazing and remarkable sights that the Wirral has ever seen. It is these local tragedies which I have attempted to resurrect. The charming but often rose-tinted memories of Wirral’s past have been recounted time and time again. We know about Laird’s fantastic vision for the ‘City of the Future’. We know of the marvellous work carried out by Lord Leverhulme and of his commendable industrial ambitions for Port Sunlight. We understand the niceties of Wirral and its illustrious history, but our peninsula’s sometimes unpalatable past is often left unexplored.

The accidents and disasters featured in this book are all true, and they make saddening but nevertheless fascinating reading. Let us hope that such tragic occurrences are banished to the past. C’est la vie.

Daniel K. Longman

A DEADLY DOSE

On the evening of Saturday 1 April 1893, Frederick Clavey, an outdoor manager to a firm of ship painters, returned to his home at 51 Chestnut Grove, Tranmere. He had just completed a hard day’s work and was keen to check up on his wife Dora, who had been very poorly since Easter Tuesday. On entering the house he made his way up the stairs to the master bedroom.

‘Good evening dear’, Frederick said cheerfully.

He noticed that his wife was fast asleep; understandably still feeling weak from the exhausting illness she was battling against. Strangely, she was lying face down.

Frederick quietly walked over to Dora and took hold of her hand. ‘Are you going to get up dear?’

Frederick’s heart skipped a beat as he realised that something was very wrong with his wife. She was not moving and did not even appear to be breathing. Mr Clavey at once rushed out of the bedroom and down the stairs, much to the astonishment of his three young children, the two servant girls and Dora’s younger brother. Without a word, Frederick flew out of the front door at a tremendous pace and into the street in search of Dora’s physician, Dr William Johnston. The speed of Frederick’s actions caused him to slip on the kerb, painfully spraining his ankle as he fell awkwardly onto the road. He gritted his teeth and hobbled across Derby Road to find the doctor on the doorstep of his home at 2 Elm Grove.

Chestnut Grove, Tranmere, taken from a map dated 1899.

Frederick quickly described his wife’s seemingly comatose state to the doctor and the two of them immediately rushed back to Chestnut Grove.

The doctor went into the bedroom and conducted a swift examination of Mrs Clavey. His face soon registered a look of terrible confusion and perplexity. The doctor’s expression confirmed Frederick’s worst fear; his wife was dead.

Doctor Johnston was left utterly bewildered at how Dora had died so suddenly. Only earlier that morning he had spoken to her and she seemed quite merry and alert. He searched the bed and discovered a small half-empty bottle under the pillow. It was labelled, ‘Poison, chloroform. R.D Evans, chemist’. His professional nose detected the unmistakable scent of chloroform, but he had never prescribed it. Dr Johnston searched further, suspecting that perhaps Mrs Clavey had used a handkerchief to administer the medicine herself. However he could find nothing of the sort and thus suspected the woman, who was now lying dead only a matter of inches away from him, to have drunk the poison straight from the bottle.

On Monday 3 April an inquest into the death of the twenty-two year old was formally opened at the Park Hotel, Charing Cross. After hearing what had happened that sad Saturday night, the coroner, Dr Churton, enquired about the actual cause of Mrs Clavey’s death.

‘Had your wife been in the habit of taking medication independent of what might have been prescribed?’ he asked Mr Clavey.

‘Some two years ago, when she had a serious illness, I heard something of that, but up to the present date I heard nothing whatever of it; in fact, I was fully under the impression there was nothing of the sort, but the doctor since tells me there has been something of that kind.’

Dr Johnston himself was then questioned.

‘Had you any reason to suspect she had taken an overdose?’

‘That was the only way I could explain what I saw after I found the bottle and from the position she was lying in.’ he replied.

The coroner continued, ‘Now, assuming that the bottle was full, would half of it be sufficient to destroy life?’

The doctor nodded. ‘Yes sir; if it was not given properly and carefully watched it would kill them.’

Bella McGuinness, an eighteen-year-old girl who had been employed as nurse to the Claveys for sixteen months was next to be questioned.

She deposed that between two and half-past on that Saturday afternoon, her mistress gave her a note and a small bottle in an envelope. She said that she was told to take them to Mr Evans the chemist in Greenway Road. Bella claimed that she had not seen the bottle before, but it was not the first time she had been sent on such an errand. On her return Bella recalled that she handed the bottle to Mrs Clavey and left her to rest. She stated that she had visited the bedroom three or four times after. The first such occasion she claimed to have heard Mrs Clavey breathing very heavily, almost as if she was sobbing in her sleep.

51 Chestnut Grove as it looks today.

‘Have you ever heard her breathe so heavily before?’ the coroner asked.

‘No sir, I did not. That was about half-past three.’

Robert Daniel Evans, a forty-year-old chemist and druggist, was called to be questioned. He stated that he could remember Bella McGuinness coming into his store at 5 Greenway Road and handing him an envelope with a bottle and a note. It read,‘A shilling’s worth of chloroform, Mrs Clavey’

‘Have you ever prescribed the stuff before?’ Mr Evans was asked.

‘Several times.’

‘The same quantity?’

‘Yes, a shilling’s worth, an ounce.’

The coroner was keen to understand all of the facts.

‘How long was it since you supplied it before?’

‘They came four times last week. I refused it twice, and gave it twice.’

The coroner persisted and maintained his torrent of questions.

‘Had Mrs Clavey ever fetched it herself?’

‘Yes sir. If I refused anybody else, she would come next day and get some other things, amongst them camphorated oil. She used to say she was going to mix the oil with the chloroform for rubbing.’

With all the answers given, the coroner began summing up the case. He was of the firm belief that the deceased had evidently taken a deadly dose of poison, and no doubt had taken it to relieve the pain she had been suffering from for a considerable period of time. The jury might say that she took poison, and that when she took it Mrs Clavey knew that she was committing suicide. On the other hand, they may believe that the woman had inadvertently taken an overdose for the sole purpose of relieving pain. For his own part Dr Churton did not feel inclined to believe Dora had taken the poison to take her own life.

‘No, no. She did not do it intentionally!’ a juror interrupted.

The jury soon returned a verdict that Mrs Clavey died from an overdose of poison, inadvertently taken.

AN UNINTENDED LIBATION

On the afternoon of 28 May 1913 Mr Kay of 4 Water Street was driving a horse and cart down Market Street, Birkenhead. He was employed by the brewery Mackie and Gladstone, and was transporting a number of casks filled with beer and minerals from the factory in Hamilton Street.

At the junction of Argyle Street, Mr Kay took a firm grip of the reins and ordered his two horses to trot across the thoroughfare. As the cart was crossing the second set of lines built into the road, a large tram, the number 51 bogey car, came hastily towards it. On seeing the cart the conductor quickly applied the brakes, causing the many passengers on board to jolt forward in their seats. For a moment or two it appeared as if the tram would clear, but as the screech of the breaks cried out, the cart was flung mightily towards the pavement in one swift hit. The horses were shaken and appeared quite disturbed, but Mr Kay was unharmed and was quick to keep them under control. The cart’s rear wheel was jammed against the pavement before ultimately breaking off, causing the casks to tumble and fall onto the road. The force of the fall caused beer to flow copiously down Argyle Street, as broken bottles lay strewn across the whole street. The flowing liquor gave the accident a more serious appearance than was warranted, and soon a large crowd had gathered around the alcohol-laden puddles to take a closer look at the afternoon mishap.

The junction of Market Street and Argyle Street, Birkenhead, 1912.

The view down Argyle Street with the junction in question in the distance, c. 1900.

The corner of Market Street and Argyle Street, 2007.

Traffic was brought to a standstill as the cart was eventually carried away, minus a wheel, by a number of local men. The tram was not damaged and continued on its way to Woodside.

MERSEY FIREWORKS

In the year 1864 one of the most destructive scenes the Wirral has ever seen took place. Scores of people living on both sides of the river witnessed the terrible yet breathtaking incident that caused widespread fear and panic throughout the area.

On the cold winter’s night of 15 January the Lottie Sleigh, an African trading barque was moored on the Mersey. She was being loaded with supplies from the Tranmere magazine boats; these included a total of eleven tons of gunpowder.