4,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Amber Books Ltd

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

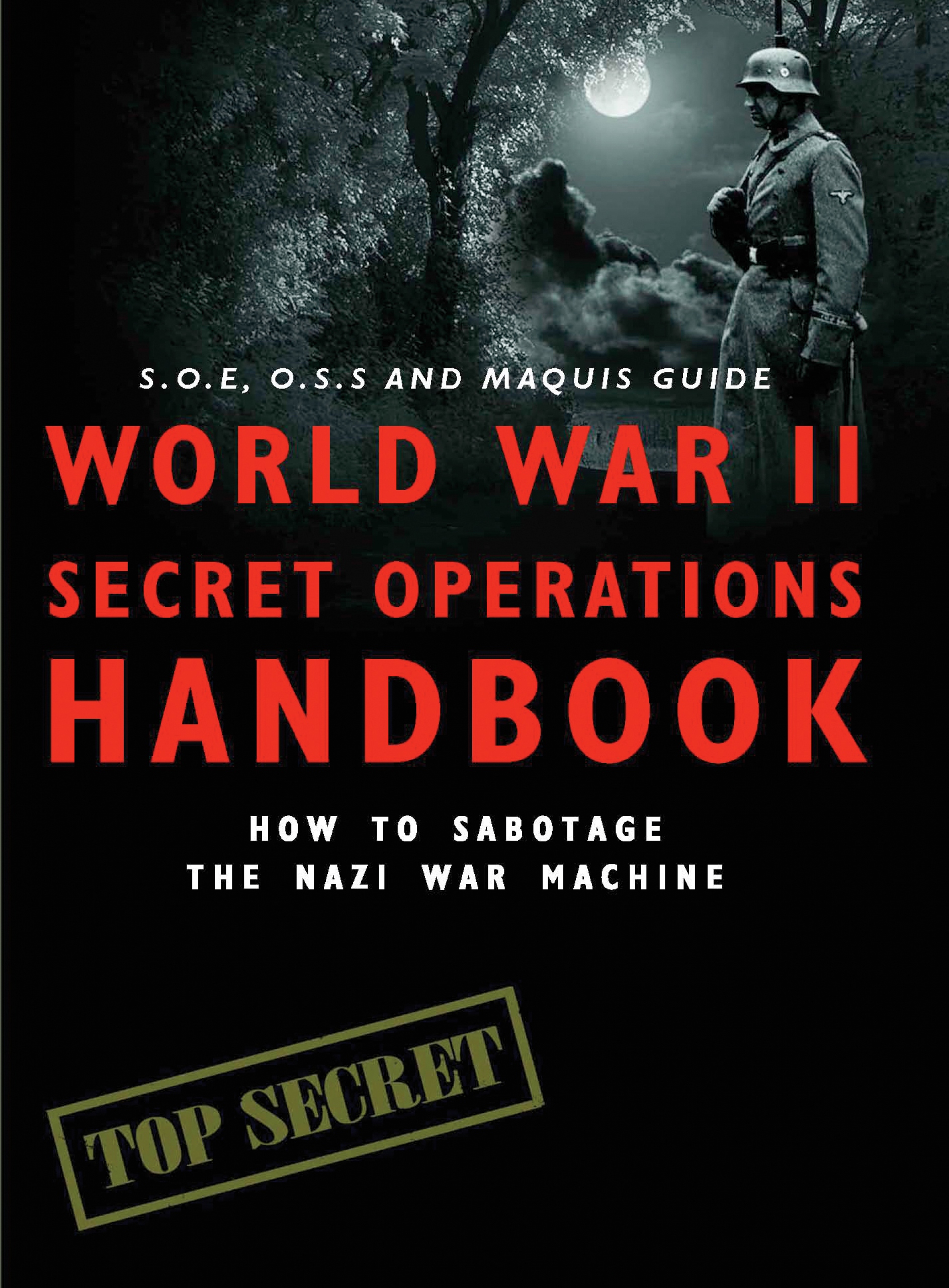

The World War II Secret Operations Handbook lets you in on the skills and tricks used by the British SOE (Special Operations Executive), the US OSS (Office of Strategic Services), the French Maquis, and other special forces in combat in Europe, Africa and Asia between 1939 and 1945. Learn how to rig up a makeshift radio, how to pass undetected in enemy territory, how to live off the land and make shelter, and how to work as a sniper. Learn how operatives blow up bridges, roads, railways and arms depots and how they work with the local resistance. Presented in a handy pocket-size format, the World War II Secret Operations Handbook takes the reader from arrival in enemy territory through survival, accomplishing a mission and finally ensuring sound exit strategies. The book also includes a number of sidebars on real life secret operations from World War II. With more than 120 black-&-white artworks and with easy-to-follow text, the World War II Secret Operations Handbook is an excellent guide to the techniques and skills used by the men and women of the special forces, techniques that are as relevant today as they were in 1945.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 307

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

WORLD WAR II

SECRET OPERATIONSHANDBOOK

STEPHEN HART AND CHRIS MANN

This digital edition first published in 2018

Published by Amber Books Ltd United House North Road London N7 9DP United Kingdom

Website: www.amberbooks.co.uk Instagram: amberbooksltd Facebook: amberbooks Twitter: @amberbooks

Copyright © 2018 Amber Books Ltd

ISBN: 978 1 782741 03 9

PICTURE CREDITS All illustrations © Amber Books Ltd

All rights reserved. With the exception of quoting brief passages for the purpose of review no part of this publication may be reproduced without prior written permission from the publisher. The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. All recommendations are made without any guarantee on the part of the author or publisher, who also disclaim any liability incurred in connection with the use of this data or specific details.

www.amberbooks.co.uk

CONTENTS

Introduction

1. Insertion

2. Behind Enemy Lines

3. Working Under Cover

4. Intelligence Gathering

5. Sabotage

6. Combat

7. Extraction

Further Reading

Index

INTRODUCTION

As World War II raged across the land-based fronts in Europe (and Southeast Asia), in the skies above and across the seas of these regions, another bitter struggle played out across some other, less obvious, front. This was the clandestine conflict waged by secret operatives – secret agents, spies or ‘fourth columnists’ – undertaking secret operations behind enemy lines to ‘set Europe ablaze’. During this bitter cloakand-dagger struggle, courageous secret operatives, having undergone specialized training and wielding ingenious equipment, pitted their wits against those of the enemy. These agents searched out the enemy’s weaknesses and engaged them, thereby making a significant contribution to the war’s eventual outcome.

All combatants of World War II developed dedicated organizations to control the behind-the-lines operations waged by special operatives. The United Kingdom’s principal such organization was the Special Operations Executive (SOE), although the Special Intelligence Services (SIS) also undertook secret agent missions. The United States’ equivalent was the Office for Strategic Services (OSS), while the Gaullist French regime-in-exile developed the Central Bureau of Intelligence and Operations (BCRA). Finally, in Nazi-occupied Europe local Resistance networks emerged that also fought (often with the help of SOE, OSS and BCRA) a clandestine partisan struggle against their Axis occupiers. These movements included the Maquis in occupied France, PAN in The Netherlands, Milorg in Norway, ELAS, EDES and EKKA in Greece, and the Partisans in the Soviet Union. Finally, in Hitler’s Reich the armed forces counterintelligence agency (Abwehr), the Nazi Party’s SS Security Service (Sicherheitsdienst – the SD) and the Secret State Police (Gestapo) spearheaded Germany’s own secret operative war.

Secret Operations Techniques

But how did these secret operatives wage this cloak-and-dagger struggle against the enemy behind its own lines? This is what this work sets out to explain. It investigates the strategies, organization, tactics, techniques, skills, training, weapons, equipment, communication devices, operations, missions and intelligence that underpinned this desperate lifeand-death struggle.

The World War II Secret Operations Handbook takes you deep into the murky covert world of the secret operative. Often, this is a fantastical world, filled with awe-inspiring human courage, bizarre technological gadgets, amazing specialized skills, cutting-edge training, and the human arts of ingenuity, guile and deception.

Main Gestapo HQs in Occupied Europe

The security services of the German occupation forces inevitably tended to establish themselves in the existing centres of power. The Gestapo (Secret State Police) along with the Nazi Party’s Security Service (Sicherheitsdienst) under the umbrella of the Reich Security Main Office (Reichssicherheitshauptamt – RHSA) was no exception, establishing a major office in most capital and some major regional cities.

Ever wondered how a functional pistol could be designed to fit into an agent’s belt buckle? Have you mused on how an agent might escape from his prison cell using only discarded cans of sardines? Want to know what an agent might need to add to cement mix to render enemy concrete fortifications fragile? Ever pondered on how an operative can overpower a vigilant armed guard, and kill him using his/her bare hands?

This work tells you how to do all this, and much more besides. It unravels the key techniques involved in the secret operative’s deadly trade and describes some of the most important missions undertaken using these skills.

Chapter Breakdown

Each of the seven chapters in the World War II Secret Operations Handbook examines one part of the typical covert mission cycle. Chapter 1 (‘Insertion’) examines the techniques and tactics employed to insert secret operatives into enemy-held territory. This explains how an agent was successfully inserted at night by light aircraft onto a small improvised grass landing strip, or by submarine and canoe onto a deserted shoreline.

Chapter 2 (‘Behind Enemy Lines’) investigates the methods by which secret operatives lived off the land and survived behind enemy lines. It recounts how agents obtained food and water, made shelters, kindled fire for warmth and cooking, navigated by the stars, and a whole host of associated techniques that they used to survive.

Chapter 3 (‘Working Undercover’) describes how agents were able to operate behind enemy lines. This recounts how operatives made contact with local Resistance groups, rigged-up makeshift radios, worked out security procedures to foil enemy countermeasures, and other practical operational details.

Next, Chapter 4 (‘Intelligence Gathering’) analyzes the ways in which operatives gathered information about the enemy. It discusses the skills and techniques involved in effective visual surveillance of a target, and the tactics of telephone tapping.

Chapter 5 (‘Sabotage’) and Chapter 6 (‘Combat’) explain how operatives took the fight to the enemy. The first of these chapters examines the methods employed to sabotage enemy installations. It investigates the methods operatives employed to disrupt an enemy railway system, disable an enemy tank factory, and render enemy concrete fortifications brittle.

In the Shadows

When crossing a road or any open space, agents and Resistance fighters took advantage of shadows thrown by trees, buildings and other features.

The next chapter explains how secret operatives carried out assassination strikes against key enemy leaders, mounted ambushes and raids on enemy forces, and assisted the guerrilla warfare waged by local Resistance groups.

Finally, Chapter 7 (‘Extraction’) explores how operatives escaped from the scene after executing their mission, how they were then extracted from enemy territory back to home soil and, if they were unfortunate enough to be captured, the methods they employed to escape from captivity

Norwegian Resistance Weapons

The Norwegian resistance were well supplied by the Allies. Kit for fighting units included the US-made M1 carbine, which was an ideal weapon for firefights at a distance of a few hundred metres.

Tips and Profiles

In addition to the main text, each chapter has a number of box features that describe in more detail certain aspects of these secret operations. There are four types of box feature in this work: Mission Profile presents an in-depth account of a particular operative mission, such as the SOE plot to assassinate Hitler; Tactics Tip explains how a particular operative method was employed, such as assassination using a mine; Equipment Profile investigates the technical detail of a particular piece of operative equipment and how it was employed, such as the Westland Lysander light aircraft; finally, Operative Profile provides a brief résumé of some of the war’s most (in)famous operatives, such as ‘The She-Cat’.

The work is also illustrated with numerous captioned black-andwhite diagrams or line drawings that shed extra light on the secret operative weapons, equipment, tactics, techniques, skills, training and missions discussed in the main text and sidebars.

The World War II Secret Operations Handbook, therefore, covers a wide spectrum of the techniques and skills employed during the operative’s secret war that raged behind enemy lines. These ranged from the mundane, such as how an operative camouflaged his/her face, to the fantastical – how explosive tyrebursters were made to resemble cow dung of the correct colour and texture for the local area in which they would be used. They scaled the heights of human endeavour: battered operatives held in Nazi concentration camps like Dachau somehow managing to escape; and plumbed the depths of duplicity: just who, precisely, was the treble agent ‘The She-Cat’ actually working for?

All this and more await those who leaf through these fascinating pages; unlike many operatives in the field, however, after reading their secret instructions, you will not be required to destroy these pages after finishing them!

Insertion into occupied territory could be carried out via land, sea or air. This would often involve the use of special technology, such as an S-phone or Welfreighter boat.

1

Inserting agents and resistance fighters into enemy territory can be one of the most difficult and potentially hazardous parts of any clandestine operation.

Insertion

By the late summer of 1940 the newly formed Special Operations Executive (SOE) faced considerable difficulty in ‘setting Europe ablaze’ given that British forces had been ejected from the Continent following the evacuation from Dunkirk and subsequent fall of France. Thus virtually all efforts to undertake covert action in Nazi-occupied Europe required the insertion of agents from the United Kingdom and this meant crossing the Channel or, in the case of Norway, the North Sea. Thus SOE developed a whole series of techniques for transporting its members and equipment for the European resistance members it was supporting by sea and by air. The organization became skilled in the use of boats, submarines and aircraft, either landing or making drops by parachute.

The situation changed once Allied forces returned to mainland Europe via Italy in the autumn of 1943 and then into Normandy in June 1944. Although aircraft remained the mainstay for inserting agents and resupply, other, more traditional, means of moving through enemy lines and into their rear areas could be used. For the Soviets this was always the situation. In the campaign following the German invasion of June 1941, as the need to move through frontline areas was a constant requirement for Soviet Partisans, great consideration was given to the best means by which to cross through the front line.

By Air

For SOE, the key delivery system of both agents and supplies was the aircraft. There were two methods: the agent could be dropped off by a plane which had landed or make a parachute jump. Both had advantages and disadvantages. Parachuting meant less risk to the aircraft but did mean that agents and supplies might be scattered, damaged or both. Landing put the aircraft and pilot in greater danger, but allowed for greater precision and made injury to passengers and damage to equipment less likely. It also meant that verbal messages could be passed and agents extracted on the same trip.

At the end of Group A training prospective agents took the parachute course at Special Training School (STS) 51 at Manchester’s Ringway airfield. Agents’ first sessions were spent being dropped from special harnesses on to crash mats to simulate landings. This then progressed to jumping from a 23m (75ft) tower and then to a static balloon 213m (700ft) up. Finally, there came three daylight drops from an aircraft and two at night. The students needed to master basic parachute landing technique and learn the necessity of keeping both legs together to lessen the chance of breaking something. This had to become instinctive as there would be no time to think when the time came for real.

Aircraft Employed

The aircraft that operated in support of SOE were usually obsolete or obsolescent bombers. The RAF’s Bomber Command was loath to equip the squadrons that supported SOE with modern aircraft. Air Chief Marshal Sir Charles Portal, Chief of the Air Staff, told SOE that ‘your work is a gamble which may give us valuable dividend or may produce nothing. It is anybody’s guess. My bombing offensive is not a gamble, its dividend is certain; it is a gilt edged investment. I cannot divert aircraft from a certainty to a gamble which may be a gold-mine or may be completely worthless.’ As a result, the number of available aircraft was small, certainly in comparison to the vast bomber fleets sent against Germany and other targets in occupied Europe.

Only five British-based aircraft were to work with the Resistance until August 1941. By the end of the following year it was still under 30 and the number of aircraft available to SOE on a full-time basis never passed 60. Two squadrons, No. 138 and No. 161, undertook the missions from a carefully disguised aerodrome at Templeford near Cambridge.

Allied Aircraft Types

RAF support for SOE was largely in the form of its ageing heavy bombers. Initially, the Whitley and later aircraft such as the Wellington and Halifax dropped agents and supplies across Europe.

Occasionally, the base at Tangemere in Kent was made available and extra support could occasionally be loaned from Transport or Bomber Command. The USAAF added two more squadrons flying Liberators and Dakotas in January 1944.

Equipment Profile:The Westland Lysander Mark III

The Westland Lysander was designed as an army cooperation and light support aircraft. It entered service in 1938 and saw action in France in 1940, which exposed its limitations as a frontline combat aircraft. However, the ‘Lizzie’, as it was known, really came into its own as a support aircraft for SOE and Britain’s intelligence services. The aircraft’s sturdiness, manoeuvrability and extraordinary ability to take off and land within a small area made it ideal for clandestine work. As SOE’s official historian, M.R.D. Foot wrote, ‘as Voltaire said of God, that had it not existed it would have had to have been invented’.

Crew: 1Passengers: 1–2 (3 at most).Powerplant: One 649kW (870hp) Bristol Mercury XX 9-cylinder air-cooled radial engine.Performance: Maximum speed 341km/h (212mph) at 1525m (5000ft); service ceiling 6555m (21,500ft).Fuel Capacity: 482 litres (106 Imperial gallons) in a fuselage tank. The Lysander Mk IIISCW could carry an external long-range tank of 150 Imperial gallons (682 litres) could also be carried to extend the range.Range: 966km (600 miles) on internal fuel; 1448km (900 miles) with external tank.Weight: Empty 1980kg (4365lbs) with a maximum take-off weight of 2865kg (6318lbs).Wing Span: 15.24m (50ft).Length: 9.3m (30ft 6in).

So, when planning air drops, the relative working radii of the aircraft had to be taken into account. The Armstrong Whitworth Whitley could operate out to about 1368km (850 miles), the Vickers Wellington had a slightly shorter range, and the Handley-Page Halifax, a few of which were added to Nos 138 and 161 Squadrons’ roster from August 1941, had a similar range too. The Liberators used by the USAAF could reach a couple of hundred miles further. For landing agents, the preferred aircraft was the Westland Lysander, an aircraft designed for reconnaissance and artillery spotting. It was perfect for delivering agents, being sturdy, manoeuvrable and having superb short take-off and landing capabilities, although being a much smaller single-engined aircraft, its operational radius was a much shorter 724km (450 miles).

SOE also used the Lockheed Hudson, a much larger twin-engined light bomber in this role. It could carry a Rebecca airborne receiver for the Eureka homing beacon and comfortably carry 12 men or a ton of stores. However, it required a kilometre or so of flat meadow in which to land and take off. So the range of these aircraft meant that large areas of Eastern Europe, such as eastern Poland, Finland and the USSR, which was particularly wary of aircraft operating for foreign secret services anyway, were outside SOE’s supporting aircrafts’ range.

The following section is adapted from ‘The SOE Syllabus: Selection of Dropping Points and Landing Sites, July 1943’, in How to be a Spy: The SOE Training Manual.

Selection of the Drop Zone

The reception committee is responsible for selecting the drop zone. This must meet certain basic principles. Dropping operations take place on moonlit nights by aircraft flying between 152 and 182m (500 and 600ft) at 160–193km/h (100–120 mph). Therefore, an open area of ground not less than 548m (600 yards) square is required. This should be increased to at least 731m (800 yards), if several containers or men are being dropped. This area will be sufficient, whatever the wind direction. Drops should not take place if the wind speed is above 32km/h (20mph). Agricultural ground and swamps should be avoided. Ploughed fields are a physical hazard to landing parachutists and damage to the crops might leave evidence of the landing. The area should be free of telegraph or high-tension wires. While cover in the immediate vicinity is an advantage, high trees are also a hazard to be avoided.

The selection of the site must always take into consideration three major concerns:

1) The safety of the dropping aircraft.

2) The site’s easy recognizability at night.

3) The planning and make-up of the reception committee.

Aircraft Safety

To ensure the safety of the aircraft three main points should be observed:

1) The area should be away from heavily defended areas, to avoid flak concentrations. Enemy aerodromes are particularly dangerous and should be avoided at all costs.

2) The selected area should be as level as possible. Mountainous and high country should be avoided if possible, but a high plateau might be usable if it meets the correct dimensions. Valleys should also be avoided unless particularly wide.

3) The dropping aircraft must be clear of enemy territory by daybreak and, therefore, travelling times and distances (usually from the UK) must be taken into consideration.

Recognizability of Site

To ensure the site’s recognizability at night the following issues should be taken into consideration. A pilot flying at 1828m (6000 feet) on a moonlit night should easily be able to spot the following points to aid navigation:

1) The coastline, if possible with breaking surf; and river mouths over 47m (50 yards) wide.

2) Rivers and canals. Both provide moon reflection, which is helpful. Wooded banks may reduce this. A river needs to be at least 27m (30 yards) wide. This is less important with regard to canals as their unnatural straightness will aid identification. There is a danger of misidentification if the area is crisscrossed with numerous rivers.

3) Large lakes, at least half a mile wide. Care should be taken if there is more than one in the area.

4) Forests and wood blocks. Need to be at least 0.8km (0.5 miles) wide and of a regular shape. Consult a recent map in case of recent felling, which might have altered the profile.

5) Straight roads, at least 1.6km (1 mile) in length, are good navigation guides, particularly when wet. Narrow or winding lanes are of no use.

6) Railway lines. Only useful in winter when snow is on the ground as a main line cuts a distinctive black ribbon across the landscape.

7) Towns and built-up areas. In conditions of black-out, towns are unlikely to be of much use unless over the size of 20,000 inhabitants. One needs to consider the possibility of anti-aircraft defences.

It is clear, therefore, that areas of water provide the best points for quick recognition. The ideal is to have a combination of distinctive features, the last of which should not be more than 4.8km (3 miles) away from the dropping point. The drop zone itself should be marked by a system of ground lighting (see below).

It is essential that the air point of view take precedence, as it is the pilot who must make the drop. Gaining a literal ‘bird’s-eye view’ is virtually impossible, so the drop zone has to be located on a map and then a reconnaissance undertaken to confirm the site’s suitability. It is worth choosing a large number of sites, maybe as many as 20 or 30. While examining a large-scale map, a number of factors should be taken into consideration:

1) Contours and thereby the gradients.

2) The nature of the ground, i.e. marsh, heathland, woodland etc.

3) The extent/size of possible landing/drop zones.

4) Habitation in the vicinity.

5) High-tension wire and other hazards.

6) Expanses of water, rivers, lakes and canals.

Suitable sites should be reported back to headquarters using conventional map references.

Recognizability of Site

The pilot needed to be guided to the drop zone via recognizable landmarks. Water features such as the coastline, lakes and canals were best but wooded areas, towns and major road and rail links could also be used.

Examining a Map

The initial selection of a site would be done on a map, checking the gradient, nature of the ground and the presence of habitation or hazards such as water or high-tension wires.

Container Types

The drop will be made during bright moonlight in the period of five to six days either side of a full moon. Drop zones within 32km (20 miles) of the coast may be used for slightly longer periods. The reception committee needs to be available for five consecutive nights given the vagaries of this type of operation. Enough men were required to provide security and move the dropped containers. Once a request is put into headquarters, the process of organizing a drop will take at least 14 days.

The C Type containers used are 172cm by 238cm (5’ 8” by 15”) – about the size of a man – and weigh 43kg (96lbs) unloaded. H Type containers are slightly smaller, at 167cm by 38cm (5’ 6” by 15”) diameter and 4.5kg (10lbs) lighter. They contain four cells loaded with equipment and esily requires six men to handle it. A spade is usually attached for the purpose of burying the container after it is emptied. Throwing it into a suitably deep lake or river also works well. Apparently, the containers make good targets for shooting practice, but this is not encouraged by London.

Type H containers carry five different standard loads:

H1: Explosives and accessories. H2: Sten sub-machine guns. H3: Weapons. H4: Incendiary material. H5: Sabotage material.

Thus a very short message is required to place an order, for example ‘send 2 H1 and 4 H2’.

[Taken from ‘The SOE Syllabus: Selection of Dropping Points and Landing Sites, July 1943’, in How to be a Spy: The SOE Training Manual, Toronto: Dundurn, 2001.]

Considerations for Pilots

So, presuming a suitable location was found, a request for an air drop made, the request accepted and appropriate reception party organized, all that was needed was for the aircraft to find the drop zone safely. Wing Commander H.S. Verity provided notes and advice for Lysander and Hudson pilots on operations such as these. They are also useful for anyone undertaking a navigation exercise. He reckoned that: ‘By far the greatest of work you do to carry out a successful pick-up happens before you leave the ground’ and ‘Never get overconfident about your navigation … Each operation should be prepared with as much care as your first, however experienced you may be.’

His thoughts on choosing the route in and navigation very much mirrored the SOE’s advice for selecting drop zones. Once the target was established, it was necessary to pick a ‘really good landmark nearby’. Then a route needed to be worked out, ‘hopping from landmark to landmark’ while avoiding possible flak concentrations. ‘Try to arrange a really good landmark at each turning point, for example a coast or a big river.’ He recommended spending ‘two hours in an armchair reading your maps before you go’. Know the terrain either side of the route, try to memorize the shape and patterns of woods and towns and ‘the way in which other landmarks converge on them’.

Preparation

With regard to loading the aircraft – Verity was referring specifically to the Westland Lysander, the mainstay of SOE agent pick-up/drop-off operations (see Equipment Profile: The Westland Lysander Mark III) – it was possible to get four passengers in, although three was the normal recommended maximum and ‘as you can well imagine, that means a squash’. The heaviest luggage should be stowed under the seat nearest the centre of gravity. Important items ‘such as sacks of money, should go on the shelf, so they are not left in the aeroplane by mistake’. It is not difficult to imagine how easy it was to forget or mislay something while hastily exiting an aircraft in the middle of a darkened field in the middle of occupied territory. The amount of fuel carried affected the aircraft’s handling characteristics, particularly when taking off and landing. Yet it was advisable to have ‘a very large margin of safety’ of enough fuel for about two hours extra flying time, as ‘you may well be kept waiting an hour or more in the target area by a reception committee that is late turning up’ or you might get lost.

Dead Reckoning (DR)

Dead reckoning was an important part of any World War II pilot’s navigational process. Essentially, the pilot or navigator would work out where his speed and compass bearing should take him over his flight plan and then hope to marry up that information with the map and the ground below him. Wind speed and direction would be taken into consideration. It was an absolutely vital navigational tool and usually checked at least once every 483km (300 miles).

Verity’s remarks on personal emergency kit are apposite:

If you get stuck in the mud, it is useful to have in the aeroplane some civilian clothes … You should also carry a standard escape, some purses of French money, a gun or two, and a thermos flask of hot coffee or what you will. A small flask of brandy or whisky is useful if you have to swim for it, but NOT in the air. Empty your pockets of anything of interest to the Hun, but carry with you some small photographs of yourself in civilian clothes. These may be attached to false identity papers. In theory it is wise to wear clothes with no tailor’s, laundry or personal marks.Change your linen before flying, as dirty shirts have a bad effect on wounds. The Lysander is a warm aircraft, and I always wore a pair of shoes rather than flying boots. If you have to walk across the Pyrenees you might as well do it in comfort.

Thus prepared, he recommended that after a nap in afternoon, as ‘it is most important to start an op fresh’, finally you should ensure that ‘you get driven to your aeroplane in a smart American car … cluttered up from head to toe with equipment and arms and kit of every description, rather like the White Knight, prepared for every emergency’.

Landing and Take-off Pattern

The pilot flying into the wind would aim to touch the ground at about point A. He would break and then turn between lights B and C and then taxi back to point A and stop to the right of A. Then, a drop-off or pick-up would be undertaken before the pilot took off – facing into the wind

The Flight Out

Before take-off it was essential to ensure ‘the agent knows the form’. It was essential that he knew how much luggage he was carrying and where it was stowed, where the parachutes were, how the internal communication system worked and the drill for landing. If the Lysander was both dropping off and picking up agents, there was a set method for the turn around. One agent would stay in the aircraft to hand out his own luggage and then receive the kit of the homecoming agent, before getting out himself.

Once airborne, Verity preferred to cross the Channel high to avoid trigger-happy members of the Royal Navy and flak from enemy coastal convoys, and in any case, if flying low, it took a long time for a heavily laden Lysander to reach his preferred height for crossing the enemy coast as high as possible at about 2438m (8000ft). This gave a good general view and ruled out the danger of light flak. Once the point of crossing was identified, ‘you may gaily climb above any low cloud there may be and strike into the interior on Dead Reckoning (DR)’.

Verity warned of the dangers of misidentifying a landmark, ‘so never have faith in one pin point until you have checked with a second or even a third, nearby’. When it came to identifying landmarks, he broadly concurred with SOE’s instructions. As he said, ‘water always shows up better than anything else, even in very poor light’. Forests and woods were next best and often made ‘very good landmarks’, particularly if large. He was slightly more positive about railways than SOE. While admitting that ‘a railway may not be very easily seen in itself, the lie of the track may be deduced from the contours of the land’ or ‘given away by the glowing firebox of an engine’. However, the real advantage of railways ‘is that they are few and far between and therefore less likely to be confused with each other’.

Roads on the other hand ‘can be very confusing, because there are often many more on the ground than are marked on you map’. The route nationale, ‘lined with poplars and driving practically straight across country’, could be useful and roads were a reasonable way to find a town or village. However, ‘in general terms it is wiser to use roads as a check on other landmarks’. Large towns should be avoid ‘on principle’ in case of flak. ‘This is a pity, of course, because large towns are very good landmarks.’

The Landing

On the approach to the target area, after running through the cockpit drill and putting the signalling lamp to Morse ‘and generally waking yourself up’, it was time to locate the landing field. ‘Don’t be lured away from your navigation by the siren call of stray lights’, he warned. ‘You should aim to find the field without depending on lights and be prepared to circle and look for it. If the approach is made straightaway the signal may be missed because it is given directly beneath the plane. Once the light is seen, identify the Morse letter being flashed is correct.’ Once again, Verity warned:

If the letter is not correct, or if there is any irregularity in the flare path or if the field is not the one you expected, you are in NO circumstances to land. There have been cases when the Germans have tried to make a Lysander land, but the pilot has got away with it by following this very strict rule. In one case where this rule was disobeyed, the pilot came home with thirty bullet holes in his aircraft and one in his neck, and only escaped with his life because he landed far from the flare path and took off again at once. Experience has shown that a German ambush on the field will not open fire until the aeroplane attempts to take-off having landed. Their object is to get you alive to get the gen, so don’t be tricked into a sense of security if you are not shot at from the field before landing. I repeat, the entire lighting procedure must be correct before you even think of landing.

Landing Using Landmarks

More skilful pilots could land their aircraft in a hidden location, such as between rows of trees or bushes. But such manoeuvres were only possible if the landing took place during daylight, which brought many dangers, including detection by enemy ground forces and threats from enemy fighter aircraft.

Typical Ground Beacon Layout at the Drop Zone

In an open field about 607–914m (2000–3000ft) long, three red lights would be set up 91m (300ft) apart, with a fourth white light set up perpendicular to the third light. This light would flash the morse recognition signal. The dropping plane would approach at 152m (500ft) on the drop axis against the wind as slowly as possible and would begin dropping the containers on the second light.

The actual landing was something that would have been practised time and time again in training. ‘On your first operation’, Verity reckoned, ‘you will be struck by the similarity of the flare path to the training flare path and until you are very experienced you take your time and make a job of it’. The first thing to do was to take a compass bearing on the landing lights and circle and check all the lights were where they were expected to be.

‘The approach in should be steep to avoid trees or obstacles’, Verity added. ‘You should not touch down before the first landing light or more than 50 yards [46m] beyond it. Use the landing light if necessary in the last few seconds but turn it off the moment the aircraft touches the ground. Taxi to the light where the agent will be standing and then turn the plane around so it points back the way for take-off.’

Verity counselled that: ‘At this point you may be in something of a flap but don’t forget any letters or messages you may have been given for the agent.’ Once given the okay, it was a case of – ‘off you go’.

The Flight Back

On the return journey, it was very important not to relax and forget the importance of navigation on the way back, as it was necessary to avoid flak concentrations. One could not ‘just point your nose in the direction of home. … for the sake of your passengers, you should not get shot down on the way back. So navigate all the way there and back.’ In double pick-ups, Verity advised caution in radio communications, as ‘German wireless intelligence is probably listening with some interest to your remarks’, so no reference other than code words should be made to the landing area.

In conclusion, Verity noted the ‘good will which exists between pilots and agents’ and that ‘all pilots should realise what a tough job the agents take on and try to get to know them and give them confidence in pick-up operations’.

He recognized that this could be difficult ‘if you don’t speak French and the agent doesn’t speak English, but don’t be shy and do your best to get to know your trainees and passengers and let them get to know you’. He finally pointed out that such operations are ‘perfectly normal forms of war transport’ and should not be mythologized as if they were ‘a sort of trick-cycling spectacle’. Professionalism and proper preparation should ensure success on virtually every occasion.

Operative Profile:Wing Commander Hugh Verity (1918–2001)

Hugh Verity joined the RAF shortly after the outbreak of World War II. In the winter of 1942, after service with RAF reconnaissance and night fighter squadrons, he volunteered for No. 161 Squadron, which supported SOE operations, and was accepted. He went on to fly around 30 Lysander missions into France, once with Jean Moulin, leader of the Gaullist Resistance, as passenger. He was a skilled, resourceful and determined pilot. He was also popular with his charges and the reception committees on the ground due to his calm, friendly demeanour, helped not least by his ability to speak French. Verity was awarded the DFC and DSO for his exploits and the Legion d’Honneur in 1946. He later became an SOE air operations officer organizing drops and landings across Western Europe and Scandinavia, and in the autumn of 1944 moved to Southeast Asia to supervise clandestine air operations there. He continued to serve in the RAF after the war before retiring in 1965.

Guiding the Aircraft into the Target Area

These operations needed a direct link between the men on the ground and the air crew. Once Verity or one of his colleagues had located the drop or landing zone, the whole process was much facilitated if ground-to-air communications were available. Landing lights could do the job. In remote areas of the Balkans bonfires could be used. These, however, left evidence. Cans or containers filled with sand and dosed in petrol or paraffin could be used; these were easily doused and carried away in case of emergency. In most of Europe more discreet methods were generally used. The light signals used had to be visible from the air but must not alert hostile forces in the vicinity on the ground. The usual method was to use domestic torches or bicycle lamps. SOE supplied modified Eveready two-cell torches, which were adequate if not really robust enough. Experiments showed on a clear night four days after a full moon an aircraft flying at 305m (1000ft) could see a visual signal at a range of 8km (5 miles). Coloured filters – red, amber, green and blue –were issued with the torches; and of these, red and green were the easiest to spot. Lighting on the field was absolutely central to landing an aircraft or conducting a parachute drop, but the whole process was much facilitated by the introduction of the S-Phone, a shortwave radio telephone that allowed the aircraft (or ship) to home in on the ground station (carried in the pack of the operator) and also pass verbal messages between pilot and operator. It could be fairly easily carried by the man on the ground but could not really be explained away if caught in possession of the device by the enemy.

Using an S-Phone Type 13/MkIV (1943)

The S-Phone was remarkably easy to use, functioning in essentially the same way as a telephone. That said, the set was directional and the operator had to be facing into the path of the oncoming aircraft.

Equipment Profile:S-Phone

Specifications Transmission frequency: 337 megacycles.Reception frequency: 380 megacycles.Power output: 0.1–0.2 watt.Dimensions: 19 x 10 x 50cm (7.5 x 4 x 20in).Weight: 1kg (2.25lbs).Total weight: 7.7kg (17lbs) (including harness, batteries etc)

Use of the S-Phone

The S-Phone could be used for three distinct purposes: radiotelephone, homing beacon and parachute drop spot indicator.