9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Born in England to an Italian Fascist father, Peter Ghiringhelli's turbulent childhood saw him deported to Italy when Mussolini fatefully entered the Second World War. There Peter witnessed the totalitarian regime at first hand and recalls his experiences of cold and hunger, his own role in Fascist rallies as a member of the black-shirted Balilla and the fall of Mussolini, providing a captivating living link to the past. Published for the first time, his childhood memories of this part of war-torn Europe are a fascinating insight into life under terrible oppression by the Republican Fascist party and the invading German army, who selected random Italian civilians for execution as retribution for every German soldier killed during the violent partisan fighting. Although his experiences were typical of many children living in Mussolini's Italy, Peter Ghiringhelli's remarkable recall and vivid memories serve as a unique testament to an extraordinary period of history, placing the reader in his place in a tug of war between life and death, desolation and victory. Peter Ghiringhelli was born in Leeds in 1930. After the war he joined the British army and served in the Royal Artillery in Germany and the Far East until 1953. He then worked in the Immigration Service at Folkestone and Heathrow, retiring in 1987. He now lives in Lincoln with his wife Margaret.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Ähnliche

A BRITISH

BOY IN

FASCIST

ITALY

A BRITISH

BOY IN

FASCIST

ITALY

PETER GHIRINGHELLI

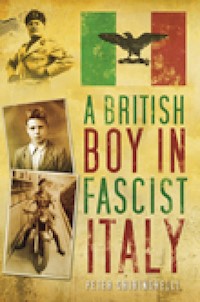

Cover illustrations. Front, top, left: Benito Mussolini (London Illustrated News); top, right: flag of the RSI; middle: author’s ID card photo, 1944; bottom: author in Hong Kong, 1952. Back: Italian immigrants from Manchester and Leeds, 1910.

First published 2010

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Peter Ghiringhelli, 2010, 2013

The right of Peter Ghiringhelli to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9677 1

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Abbreviations

Introduction

1.

Pre-war Days in Leeds

2.

The Phoney War

3.

Italy Declares War

4.

Monarch of Bermuda

5.

Conte Rosso

6.

Arrival in Italy

7.

Musadino

8.

An Interlude at the Seaside

9.

Return to Musadino

10.

While my Father was in the Army

11.

My Father’s Return Home

12.

Fall and Rise of Il Duce

13.

German Occupation and the Battle of San Martino

14.

Race Laws and Persecution of the Jews

15.

The Republic of Salò Slides into Civil War

16.

Food Shortages and a Brush with the SS

17.

Death and Destruction from Lake Maggiore to Santa Maria del Taro

18.

A New Job

19.

The War Ends in Italy

20.

My Time with the ILH-KR

21.

Another Trip to the Seaside

22.

Home Again, and on to Varese

23.

The Long Journey Back to Leeds

Notes

Bibliography

ABBREVIATIONS

British

ARP

Air Raid Precautions

HMS

His Majesty’s Ship

ILH-KR

Imperial Light Horse and Kimberley Regiment

Lt-Cdr

Lieutenant Commander

SS

Steamship (as prefix to ships’ names)

Italian

Anti-fascist:

CLN

Comitato di Liberazione Nazionale (Committee for National Liberation)

CLNAI

Comitato di Liberazione Nazionale per l’Alta Italia (Committee for National Liberation for Northern Italy)

GAP

Gruppi di Azione Patriotica (Patriotic Action Groups)

PSI

Partito Socialista Italiana (Italian Socialist Party)

Fascist:

ENR

Esercito Nazionale Republicano (National Republican Army)

GIL

Gioventù Italiana del Littorio (Italian Fascist Youth Movement)

GNR

Guardia Nazionale Republicana (Republican National Guard)

MVSN

Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale (National Militia for National Security)

ONB

Opera Nazionale Balilla (Italian Fascist Youth Movement)

RSI

Republica Sociale Italiana (Italian Social Republic)

X-MAS

Decima Flottiglia Motoscafi Antisommergibili (Tenth Anti-Submarine Torpedo Boats Squadron)

rastrellamento

Literally ‘a raking’, but used to describe anti-partisan operations and searches carried out by Republican Fascist and German forces

German

KdS

Kommandure Sipo-SD

(SD Regional Command)

SD

Sicherheitsdienst (Security Service)

SS

Schutzstaffel (Elite Guard)

SS-Aussenposten

SS Forward Commands

SS-Oberstgruppenführer

SS Colonel-General

SS-Gruppenführer

SS Lieutenant-General

SS-Hauptsturmführer

SS Captain

SS-Sturmbannführer

SS Major

SS-Scharführer

SS Sergeant

SS-Rottenführer

SS Corporal

INTRODUCTION

More than an introduction, I think a word of explanation is required. Between June 2003 and January 2006, the BBC asked the public to contribute their stories of World War Two to a website called ‘WW2 People’s War’. The submitted material, amounting to 47,000 articles and 15,000 images, is now permanently archived.

In November 2003, after several prompts from my wife Margaret, I decided to submit my story under the title A Childhood in Nazi-occupied Italy. The limit for submitted contributions was 2,000 words and I condensed my story to fit that limit. Then in late 2008 Sophie Bradshaw, a commissioning editor for The History Press, having read my account, contacted me and suggested that I should expand it for publication. This book is the result.

I kept no diaries in Italy, nor did I subsequently write anything down, so all is based on my memory. The problem, of course, is that human memory is fallible. I wrote my story for ‘WW2 People’s War’ exactly as I remembered it, but afterwards when I came to consult others, especially those in Italy, I found that I had often been mistaken in dating events. Unfortunately, it is not possible now to access my original BBC account to correct it. Wherever there is a discrepancy between the two versions, the one given here, based on detailed research, is the more accurate.

Throughout the book, Fascist (spelt with a capital F) refers to members of the Italian Fascist Party, and Partisan (with a capital P) refers to a member of an Italian Partisan Group, otherwise I have used lowercase. Where fascist and partisan appear in cited official documents, I have retained the original lowercase.

I should like to thank my dear friend Clara Fortunelli in Vicenza for tracking down obscure books in Vicenza’s public library and scanning pages for me; also Roberto Rivolta, a boyhood friend, now living in Luino on Lake Maggiore, for reminding me of events and shared experiences and sending me photos; and Pancrazio De Micheli in Porto Valtravaglia for giving me permission to publish photos of years gone by, which have appeared in a series of yearly calendars of the Valtravaglia, for which he is the co-ordinator; and finally Margaret, my wife, who has been a great help in patiently reading and correcting the manuscript.

1

PRE-WAR DAYSIN LEEDS

For many decades after the Second World War, those who had lived through the war divided time and their lives into two distinct periods, always known as ‘before the war’ and ‘after the war’. ‘Before the war’ is a half-forgotten age, a different world, a dim and distant past. Leeds before the war was a black city, literally; all its stone buildings were black with decades of grime and soot, typical of a northern industrial city, before the post-war Clean Air Act was introduced and the many splendid Victorian municipal buildings sand-blasted clean. Gas lamps were everywhere and gas lamp lighters still made their rounds carrying lamp-post ladders; known as ‘knocker-uppers’, they also knocked on bedroom windows to wake people up for work in the mills and factories. There were no pedestrianised areas or one-way traffic systems then; it was a city of clanking trams, solid-tyred lorries, many cars, but even more bicycles and horse-drawn carts, and the roads had many water troughs for horses to drink from. Order started to be made of the traffic chaos in 1934 with the introduction of the Transport Secretary Leslie Hore-Belisha’s pedestrian crossings, with glass orange lights which inevitably became known as Belisha Beacons, the forerunners of post-war zebra crossings. Life in Leeds seemed to be regulated by factory whistles and sirens, especially at five and six o’clock, when thousands of factory workers poured out onto the streets on foot and on bicycles, and long queues formed at tram stops.

But my father wasn’t a factory worker; he was a knife grinder, an Italian immigrant who had arrived in Leeds in 1920 at the age of 16. He came to work for Peter Maturi, an uncle by marriage, a cutler who had emigrated to Leeds in the late 1890s. My father didn’t look like the stereotypical olive-skinned Italian; he had fair hair and grey-blue eyes, probably inherited from his mother, Mathilde Skenk, of Austrian descent who was from the South Tyrol; my paternal grandfather, who I never met, was also a fair-complexioned northern Italian. My father had a flair for languages and was already fluent in French as well as Italian (most Italians then spoke regional dialects and not Italian), and he quickly learned English both spoken and written.

My mother, Elena Granelli, on the other hand, despite her Italian name, neither spoke nor understood any language other than English. She was born in Leeds in February 1905. Her parents, Ferdinando and Maria (née Molinari), were initially ice cream makers who had also settled in Leeds in the late nineteenth century. My mother, in her late teens, sold ice cream from a cart in Leeds City Market, and that is where she met my father. He worked nearby in George Street and used to pass her as he came into the market on Fridays with a large basket to collect knives and cleavers for sharpening from the butchers’ stalls. Friday was a traditional fish day and was the best day for butchers to have their knives, cleavers and saws sharpened.

Elena, always known as Nellie, was the eldest of five children; the others were Rosa, Millie, Louis and John. Rosa was taken to Italy while still an infant because the fogs and industrial smoke-polluted air of Leeds gave her severe respiratory problems, and her parents thought that she would stand a better chance of surviving babyhood in the fresh mountain air of the Apennines, where they both originated from. Rosa never returned to England; she was brought up in Pianlavagnolo, a tiny hamlet high above Santa Maria del Taro in the region of Emilia, my grandfather’s home village, and she eventually married and settled there.

My parents married in Leeds in 1928 and I was born in June 1930 in Lady Lane. The rooms they rented are now long demolished and replaced by an office block. However, my earliest recollection is of our rented semidetached house in Longroyd Street, in the Hunslet district of Leeds. Then recently built, and most unusual for those days, it had a bathroom with separate toilet, hot and cold water, and a front garden. My father was forever trying to invent things. He would dismantle old clocks and crystal wireless sets and experiment with them and reassemble them. A couple of years after the GPO introduced the black Bakelite Type 232 combined telephone set in 1934, my father brought home about twenty old candlestick Type 150 telephones and dismantled them. From the parts he tried to make a perpetual motion machine and was forever tinkering and adjusting it, convinced that it could be done. I need hardly add that perpetual motion is impossible, but my father was entirely self-taught and, not knowing that perpetual motion would violate both the first and second laws of thermodynamics, he just kept tinkering away.

His inventiveness did pay off in another way and by the mid-1930s my father was making a good living. This came about because he had constructed a mobile grinding contraption out of spare car parts and a motorcycle he had owned when courting my mother. He had adapted the engine to drive the grindstone through the modified gearbox, which also drove the two motorbike wheels at walking pace, giving it full mobility. It attracted much attention and was photographed and featured in a local paper. As well as doing his rounds, he still worked in George Street, especially on Fridays when hundreds of girls in scarves and shawls, workers in the many clothiers and tailors, brought in their scissors and shears to be sharpened, some with dozens of scissors from their co-workers.

We lived well and, again, most unusually for those days, by 1937 my mother had a Hoover vacuum cleaner, an automatic washing machine and an electric iron; this at a time when many Leeds houses didn’t have electricity and women used a pair of flat irons, made of solid cast iron, with one on a gas ring heating while ironing with the other. No one, of course, had refrigerators. I have good cause to remember the washing machine. After the wash, the water was discharged from the machine via a flexible pipe which terminated in an aluminium u-bend hooked onto a sink; but the only way to get the water flowing was to create a vacuum by sucking briefly on the pipe. I had watched my mother do this many times and one day, while she was away from the washing machine, I picked up the discharge pipe and sucked hard and long, filling my mouth with very hot water and caustic soda, almost instantly burning my throat and then drenching me. I tried to shout but all that came out was a strangled cry. Fortunately, my mother came quickly to my rescue. Those were the days long before Health & Safety regulations were even dreamt of!

We also had a five-valve wireless set and my dad put up a long wire antenna in the back garden so that he could listen to Italian long-wave radio transmissions. Of course, by then all the Italian news was fascist propaganda. In the late 1920s my father joined the Italian Fascisti all’Estero (Fascists Abroad) association led from Rome by Giuseppe Bastianini1 through Italian consulates abroad. Meetings were held in the Italian consulate office in Bradford and we used to travel there by tram, changing to Bradford trams at the Leeds terminus. These were social occasions and there was always an Italian buffet and a dance to Italian records.

Until 1935 I hadn’t realised that I was different from the other boys in the street, but in that year, with the Italian aggressive invasion of Abyssinia (modern-day Ethiopia), all that changed quite dramatically for me. I started to be bullied at the Protestant primary school I attended at the top of Longroyd Street. I started school at an early age because I could read from the age of 3 or 4. I cannot remember how this came about, but my mother used to sit me on her knee and read to me and gradually I associated the words she spoke with the letters on the page and soon I was reading whole sentences. None of this helped me in the schoolyard at playtime, however. Two incidents in particular stay in my mind. In one incident I was violently pushed in the locker room and cut the back of my head on the low coat hooks. The other happened in the playground when a group of boys, calling me a dirty ‘eyetie’, held me down on the ground and, with my mouth covered, made me inhale continually from a bottle of smelling salts. It was the worst pain I had ever experienced, and when they released me I was unable to get up for a few minutes. When we got back into class I tried to tell the teacher what had happened, but I got little sympathy from her and she gave me a short lecture about not going behind people’s backs telling tales. I went back to my desk and sat in a daze; later I was asked a question but I didn’t hear it and couldn’t answer even when it was repeated, so I was hauled out and made to stand in a corner wearing a dunce’s cap, a tall cone of white paper marked with a capital D which was used for this purpose. I went to school the next day but this time, at playtime, I squeezed through a gap in the bent iron railings and went home and told my mother that I didn’t want to go back, but without explaining why. She took me back to school, of course, but at the weekend my father finally got out of me what had happened. This resulted in him explaining to me what Italy, Italians and ‘Eyeties’ were, and showing me drawings of the Italian Tricolour and the Union Jack, demonstrating which was which; all very confusing for a boy of 5.

In October 1935, in response to the Italian invasion of Abyssinia, the League of Nations imposed limited and ineffectual sanctions on Italy, and in a theatrical response Mussolini called on all Italian wives to donate their wedding rings, together with any other gold, silver or bronze trinkets or copper artefacts they might have. This culminated on 18 December 1935, which was declared La giornata della fede (Wedding Ring Day). In exchange for their wedding rings, donors were given a steel ring with XIV ANNO FASCISTA – ORO ALLA PATRIA (14th year of the Fascist Era – Gold to the Fatherland) inscribed either externally or internally, as preferred, in a mock-leather presentation case.

The collection was also made in Britain, and for this memorable occasion the Italian Ambassador, Dino Grandi,2 came up from London to the consulate in Bradford to preside over the ceremony. I can remember my mother giving up her gold wedding ring there. To applause, all the married women walked up to a basket before him and placed their gold wedding rings in it as ‘a gift’ to Il Duce, and in return Grandi gave them their steel wedding rings (fede d’acciao). My mother had absolutely no interest in politics then or subsequently, but she was a very devout Catholic, as were most Italian women. In Catholicism marriage is regarded as a holy sacrament and the blessed wedding ring is part of that sacrament. But in this case the political stunt was sanctioned by the Church. Setting an example in Italy, in a blaze of publicity, the Archbishop of Bologna, Nasalli Rocca, donated his gold pastoral cross, and Queen Elena gave her wedding ring. The Bishop of Civita Castellana went further: on 8 December 1935 he sent his pastoral cross to Mussolini, saying: ‘I thank Almighty God for permitting me to see these days of epic grandeur.’3 And in October 1935 the Archbishop of Milan, Cardinal Idelfonso Schuster, celebrated a double event in his cathedral which was given maximum publicity: a Te Deum for the anniversary of the Fascist March on Rome, together with a blessing of pennants of Fascist units; in his words, ‘of the army of men engaged in carrying the light of civilization to Abyssinia’.

‘The Italian flag,’ he said, ‘is at the moment bringing in triumph the Cross of Christ in Ethiopia, to free the road for the emancipation of the slaves, opening it at the same time to our missionary propaganda.’4 With such examples, any religious qualms my mother and other wives might have had were swept away. However, my grandmother was not convinced, and what happened to the gold is anybody’s guess!

Following this I was sent to a Catholic school, St Joseph’s, where I wasn’t bullied. Most of the kids were sons of Irish immigrants and the rest were English Catholics. But it was a long daily walk to school across Hunslet Moor, nothing unusual in those days, and no boy, heaven forbid, ever went to school accompanied by his mother.

For me, the big event of 1935 was the birth of my sister Gloria Maria. She was born at home, as was usual in those days, and about a week before she was born I went to stay with a kind English Protestant couple, the grandparents of my best friend Peter who lived a couple of doors away. His grandparents lived a few miles away, but closer to my new school, my own grandparents being too far away. I have a vivid recollection of this, particularly of their hissing gas lights in the living room and bedrooms, and having to go to the outside privy with a candle. I also recall being given sweet rice pudding and lettuce without olive oil and vinegar dressing. My mother had strongly advised me never to mention that we put olive oil on salad. In those days English working and middle classes were not as cosmopolitan as they are now in their diet, and olive oil was only sold in small bottles in chemist shops for medicinal purposes, chiefly for earache. My father bought olive oil in 5-litre cans from an Italian merchant in Leeds market, where we also got our spaghetti and rice, among other things. Peter’s grandparents also very kindly gave me Heinz tinned spaghetti and I think they were somewhat surprised when I didn’t recognise it as being anything like proper food. I was glad to get home and meet my new sister a few days after her arrival on 20 September.

My father was an excellent cook; indeed, he was far better than my mother. She prepared our daily meals, but if it was a special event, such as Christmas or Easter, or a dinner with friends, he did all the cooking. I remember those meals as very festive occasions; there would be salami, olives and prosciutto (now known as Parma ham) for an antipasto, followed by clear chicken soup (made from the giblets, skin and neck of the chicken). Then there would be risotto made from the chicken stock, always with saffron and dried porcini mushrooms, collected by my father in local woods and served with chicken topped with freshly grated Parmesan cheese; and the meal ended with fresh fruit and cheese, liqueurs and a small cup of black, concentrated, freshly ground coffee. At those meals we had wine, nearly always 2-litre straw-covered flasks of Chianti, and from about the age of 5 I too had a glass of wine mixed with water. It is hard to imagine now, but chicken, especially a capon, was an infrequent delicacy in those days. Poultry was all open farm reared and bought fully feathered, to be plucked and cleaned at home; the battery hen system hadn’t been thought of then. I especially remember Hunslet Feast, as the annual fair on Hunslet Moor was called; among the coconut shies, freak shows and steam-driven shamrock swings and roundabouts, there was Chicken Joe’s stall always doing a roaring trade with a crowd around him listening to his patter. My dad always bought a plump capon from him for a treat the following Sunday.

Another pre-war event which stuck clearly in my mind was the sight of the German Zeppelin airship Hindenburg,5 flying very slowly over Leeds at a very low height on a clear sunny afternoon in the summer of 1936. It was so low that it gave the impression that it was about to land. This was at a time when even seeing an aeroplane in the sky was a most unusual sight. It was also the first time I had seen the swastika other than as a small drawing; there were two large ones on the rear fins of the airship. An MP for Leeds raised the matter in the Commons with the Under-Secretary of State for Air, Sir Phillip Sassoon, asking him if he was aware that on 30 June the German airship Hindenburg flew for the second time within a few weeks at a low altitude over Leeds. That this was a photographic mapping mission seems pretty obvious now, but at the time the government flippantly dismissed the suggestion.6

Shortly after this I caught scarlet fever. Today it is not considered to be a serious disease and has been practically eradicated in Britain. With a short course of antibiotics it is now easily cured, but this was far from being the case then. I was taken to Seacroft Isolation Hospital and put in an isolation room. A few days later my parents were allowed to visit me, but I hardly recognised them in long white gowns, white bonnets and face masks. A few days after this I was given a wrong injection which left me paralysed down my left side. My pillows were taken away and I was flat on my back for several weeks. At frequent intervals I had nosebleeds, and to stem these long strands of cotton wool were stuffed up my nose. On two occasions I pulled the cotton wool out as I could hardly breathe, but after the second incident my hands were put into cotton mittens day and night, and only taken off when the nurse washed me. I was fed on liquids from a pot container with a spout. On a couple of occasions, having called for the nurse several times for a urinal glass without getting a response, I wet my bed. A clean urinal glass was kept in my bedside locker but, unable to move, I couldn’t get to it. The result was a real ticking off and an uncomfortable rubber sheet being placed under me. I was told that it would not be removed until I learnt not to wet the bed. All trivial, but the injustice of it still rankles with me.

Eventually, after what seemed to me like months, I was discharged and moved to a children’s convalescent home in Roundhay, on the then outskirts of Leeds. After a few weeks there, on the spur of the moment, one evening I absconded. I walked to Roundhay Park tram terminus and took the tram to Leeds city centre and made my way to George Street, where I knew my father would be. The next day I was taken back to the convalescent home to apologise and collect my things, and that was the end of that. I went back to St Joseph’s school, although now I was supposed to have a weak heart and I wasn’t allowed to run or take part in games at school.

Meanwhile, my mother’s parents had prospered and now ran a sweetshop and tobacconists in Meadow Lane, Holbeck, adjacent to the Palace picture house. I used to love being taken to visit my grandparents, almost weekly, by my mother. My grandmother baked all her own bread and made marvellous Yorkshire pudding. One day, shortly after my recovery, we visited my grandmother’s only to discover that my mother’s youngest brother, my Uncle John, had run away from home. He was only eight years older than me, so he was about 16 or 17 at the time. None of us had private telephones then, so it was a few days after the event that my mother found out. In fact, he had joined the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, and after his initial training in Scotland he appeared home on leave in full Highland dress, complete with busby, kilt, sporran and white spats. To me he looked magnificent and I was awestruck. However, as he was not yet 18 my grandmother promptly bought him out of the army and he became an apprentice engineer. Johnny, as he was known, was a great character and had a lasting influence on me. When war broke out he volunteered as a fighter pilot in the RAF along with his school friend Charlie ‘Chuck’ Coltate, but he failed the stringent medical examination with a perforated ear drum and was rejected, whereupon Chuck withdrew his own volunteer application. Later, when Italy entered the war, as the son of an enemy alien the only options open for John to serve his country were either the Pioneer Corps or the Merchant Navy; he volunteered for the latter, as did Chuck. Both served as engineering officers on the same ships. Their first ship was torpedoed and sunk in the Atlantic. The ship had been at the front of a large convoy and they and other survivors remained in the water until the last ship fortuitously picked them up. It had been a close call; other ships had sailed by as convoy vessels were not allowed to stop.

They then both served on the SS Sacramento, which sailed from Hull to New York throughout the rest of the war. Shortly after the war, Johnny married Margaret Callaghan, who had served as a Land Army girl, and they emigrated to Canada in the 1950s and settled in Manitoba. Johnny never spoke about the war and I only heard about his ordeal from Margaret many years later, although she now cannot remember the name of the ship.

In 1938 we moved from Longroyd Street, ‘flitted’ was the term then used, to a new detached house at the top end of Dewsbury Road, within walking distance of the newly opened Rex cinema. In pre-war Leeds there were dozens of cinemas, all well attended, and it was a regular thing to see long queues in the evening for the latest films. It was called ‘going to the pictures’; no one ever called them ‘films’ or ‘movies’, and cinemas were called ‘picture houses’; the shows were continuous and you could stay in as long as you wished. Even the smallest picture houses had a uniformed ‘commissionaire’, usually a retired army warrant officer, with a peaked cap and white gloves. When business was slack he would stand outside and bellow ‘Seats in all parts!’, or if there were queues he would decide how many went in at a time. The format was always the same: a short topical feature; a cartoon; the B film; the news and next week’s trailers; then the main feature film, followed by God Save the King, at which everybody stood up.

The main picture houses in the centre of Leeds, among others, were the Assembly Rooms, the Paramount, the Gaumont, the Majestic, the Ritz and the Scala. These were all sumptuous picture palaces, some with electric organs which rose out of the floor during the intervals. At the Paramount there was community singing with the entire audience singing along to the lyrics projected on the screen, with a white dot bouncing along the words in time to the organ music. At the Queen’s Theatre in Meadow Lane around 1934 or 1935, possibly one of the first times I had been to a picture house, there were still live variety acts on stage between films, such as jugglers and ventriloquists. The Queen’s was one of the very last cinemas to do this. I used to go to the pictures regularly and often, like other kids my age, alone. If it was an ‘A’ film, where kids under 16 had to be in the company of an adult, you would ask any couple or single woman to take you in, always on the strict understanding that you wouldn’t sit with them or pester them once you got your ticket. I got in this way to see Richard Tauber in Heart’s Desire by mistake; I had thought the main film was King Kong, which I eventually saw the following week. This was at a picture house on my way to St Joseph’s school (the name of which I forget, possibly the Parkfield in Jack Lane); it was a second-rate cinema so it must have been long after both films were released.

For my eighth birthday I had a special treat in town when my mother took me to the Scala to see Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, which had just been released. Another treat that year was The Adventures of Robin Hood in brilliant Technicolor, and in late 1939 The Hunchback of Notre Dame starring Charles Laughton. The very last major film I remember seeing just after the war broke out was The Four Feathers, also in Technicolor, at the Pavilion in Dewsbury Road, along with a short film on air-raid precautions, what to do with incendiary bombs and how to cope in a gas attack. We really should have worn gas masks in picture houses for you could hardly breathe for cigarette smoke, and clouds of it could always be seen billowing in the film projection beam.

It’s a wonder, too, that we all survived without our feet dropping off. In the mid-1930s it became a craze for all the best shoe shops to have a shoe-fitting x-ray machine. Often these contraptions, known as pedoscopes, were placed in the shop entrance to attract customers. Like lots of children, I often used to put my foot in to see the bones of my foot, complete with the eyelets and nails of my footwear, blissfully unaware of the potential danger. In those days not even physicists had any inkling how lethal x-ray radiation is. I also had a kit of moulds for lead soldiers and farm animals. The idea was that you melted down your broken lead figures over a gas ring, or by burning old paint in a tin, and then poured the molten lead into the moulds. I used to make lead paperweights. But most sought-after of all the metals was mercury; if anyone had some he would proudly bring it to school in silver paper to show off.

At the time of the Munich crisis, in September 1938, we were all issued with gas masks. They were kept in a cardboard box with string to sling over your shoulder and were carried at all times. Everyone was under the impression that there was a legal requirement to do so, but although there wasn’t, the effect was the same, with people getting sacked from their employment for turning up to work without their gas mask, and accused of putting themselves and others at risk in the event of a gas attack, for it was widely believed that the war would start with bombing and deadly poison gas.

Very quickly shops began to sell leather and cloth covers for the government-issue cardboard boxes and alternative containers for gas masks, and I remember that I had a brown canvas cover for mine. At first we got into trouble for always trying them on, but the novelty soon wore off and we got to hate gas drill at school as the masks smelt of rubber and quickly fogged up. Rubbing a sliced raw potato on the inside of the visor was supposed to prevent this but it never seemed to work.

In early 1939 we got our Anderson air-raid shelter. I think it must have been February or early March as I remember that the frozen ground was still too hard for my father to dig, and the curved corrugated steel sections of the shelter lay in the garden for weeks before he dug the required deep hole and fitted it in. Contrary to what many thought, protection came from the thick layer of earth that was placed over it, and the instructions were that the excavated earth should be used for this purpose, but you still saw many with the bare shelter only partly dug in. These shelters were only issued to houses with gardens, of course, and my grandfather’s house and shop didn’t have one, so they had to use a public air-raid shelter. At first these shelters were little more than trenches dug in public parks; they had started to appear during the Munich crisis, as had huge round open tanks of water for fire-fighting.

From time to time my dad hired a car for trips to the seaside. The last time he did so was in the early summer of 1939 when we all went to Scarborough for the day. I don’t remember anything of that day except the return journey, during which, to the consternation of my mother, my dad put his foot down on a straight stretch and triumphantly announced: ‘We’re doing sixty!’ This was the fastest I had ever travelled, other than on a train, and it seemed to me as if we were flying. It never occurred to me that this would be the last time I would be in a car for the next six years.

2

THE PHONEY WAR