Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

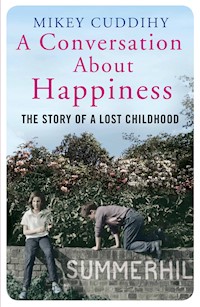

When Mikey Cuddihy was orphaned at the age of nine, her life exploded. She and her siblings were sent from New York to board at experimental Summerhill School, in Suffolk, and abandoned there. The setting was idyllic, lessons were optional, pupils made the rules. Joan Baez visited and taught Mikey guitar. The late sixties were in full swing, but with total freedom came danger. Mikey navigated this strange world of permissiveness and neglect, forging an identity almost in defiance of it. A Conversation About Happiness is a vivid and intense memoir of coming of age amidst the unravelling social experiment of sixties and seventies Britain.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 318

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

A Conversation About Happiness

Most names – apart from those of my family, and historically significant ones – have been changed to preserve anonymity. In some cases, characters have been merged. Events are as I remember them, with some fact checking for verification. For the sake of dramatization, timelines have occasionally been altered.

Photographs, my own and family ones (some of them in the public domain), along with Summerhill photos published by Herb Snitzer in his book Living at Summerhill, have acted as memory prompts. Some transcripts from Herb’s book have also been referred to, and used with Herb’s kind permission

First published in trade paperback in Great Britain in 2014 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Mikey Cuddihy, 2014

The moral right of Mikey Cuddihy to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Extracts from Summerhill – A Radical Approach to Education by A. S. Neill reprinted by permission of The Orion Publishing Group, London

Letter from A. S. Neill reprinted by permission of Zöe Readhead.

‘Totalitarian Therapy on the Upper West Side’, which appeared in New York Magazine, reprinted by permission of David Black.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade Paperback ISBN: 9781782393146E-book ISBN: 9781782393153

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For my son, James Cuddihy White

When I close my eyes, I can see her lying in the open coffin surrounded by red roses that cover her feet. She’s wearing an ugly wig, too red for her own chestnut hair with an uncharacteristic fringe. She looks strange. I put my hand out to feel if she’s real but her skin feels cold, as if she’s a waxwork, but not a very good one. I can’t equate the woman in the box with my mother. Neither can Sean or my little brother Chrissy. We giggle nervously as we kiss her, each in turn.

Contents

Part One

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Part Two

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Acknowledgements

A Note on the Author

Part One

Chapter 1

Uncle Tom picks us up from summer camp in the Catskills, all five of us. That’s me, my big sister Deedee, my brothers Bob, Sean and Chrissy. Instead of going home, we drive to the airport where we get on a plane to London for a sightseeing holiday.

I’m quite excited at the prospect of seeing the Queen.

‘I don’t want to go to England. I want to stay home and play Little League baseball,’ screams Sean as Uncle Tom drags him up the steps and hauls him into the plane.

Twenty months older than me, Sean senses that more than a holiday is afoot.

It’s late summer 1962. I’m ten years old. Kennedy is in his second year as President and Marilyn Monroe has been found dead in her bedroom from an overdose. I arrive at Heathrow in just the clothes I’m standing in: a pair of shorts and a candy-striped cotton shirt with chocolate ice-cream stains down the front. I’m clutching a white calico dachshund under my arm with the autographs of all the friends I’ve made during our six weeks at Camp Waneta. I rub my legs to combat the chill and walk uncertainly down the metal steps, squinting out at a drizzly grey sky.

They say Mom never regained consciousness. November 1961 and it’s raining. My mother turns a corner too sharply and the family Packard skids on fallen leaves. The car hits the tree. Mom goes straight through the windscreen, the steering wheel crushing her chest.

There are rumours amongst my older siblings that Mom had been on the verge of leaving my stepfather. Perhaps her death hadn’t been an accident. Another rumour has it that she’d started drinking again so was driving erratically or maybe, they speculated, she was so dosed up on tranquillizers that her reflexes were bad. My big brother Bob blames my stepfather or ‘the Gooper’, as he calls him behind his back, for being too mean to have the car fixed. One of the doors was tied shut with an old piece of washing line and he knew that the brakes were dodgy.

We all blame ourselves to some extent.

Our father died four years earlier in his own car accident, driving a much racier Ford Coupé.

Five years old, I put on a new dress my stepmother has made me. I go into the living room to show him my dress. Daddy has come home from work and is sitting in his comfortable Ezy-Rest armchair, ice cubes clinking in his whisky glass.

I do a twirl for him.

‘Very nice.’ Daddy gives an approving smile, pats me on the head, and I toddle off happily to get ready for bed.

I’m puzzled when I wake in the morning to be told that Daddy is dead. He died on his way home from the city. But I had seen him with my own eyes just last night.

So now we’re orphans.

This is where Uncle Tom steps in, setting the wheels in motion to adopt us. My father comes from a huge, Irish-Catholic family who have done extremely well in publishing on one side (Funk and Wagnalls, The Literary Digest), and inventing on the other (his grandfather was the millionaire inventor, T. E. Murray). He’s one of five brothers and two sisters who adored him; he was a tearaway, the black sheep, or Robert the Roué, as they affectionately called him, later shortened to ‘Roo’.

Uncle Tom has the same good looks as our father; his dark hair made even darker with Brylcreem, the same wry, gentle smile, a fatherly way of patting me on the head. With his soft authoritative voice, the Manhattan accent with the flattened vowels, he even sounds like Daddy. It’s difficult to tell them apart in photos, so he’s a fitting stand in as far as we’re concerned. Tom jokes that he’s ‘drawn the short straw’ when he takes us on, and I imagine my uncles sitting in my grandmother’s Park Avenue apartment drawing straws from someone’s hands – perhaps Arthur, the butler, proffering the straws like fancy hors d’oeuvres.

Uncle Tom studied economics at Harvard and went into investment banking, but after three children and a messy divorce at the age of thirty he dropped out, returning to university to take a PhD in psychology.

My sister says he kidnapped us.

Deedee is called into the principal’s office at her high school one lunchtime: ‘Edith, your uncle is here to see you.’

Deedee hasn’t seen Uncle Tom for a long time. He takes her out for lunch, to Herb McCarthy’s, a sophisticated bar and grill in town. She orders her favourite thing, a grilled cheese sandwich and a Coca-Cola.

‘How would you like to come and live with me here in Southampton? I’ve rented a place on Herrick Road just around the corner from your school.’

My sister is thinking: Uncle Tom looks rich. His plan sounds like a load of fun. Maybe I’ll get my very own Princess telephone.

‘Yes, OK,’ she says. ‘But what about the others, and Larry, and Mimmy?’

‘I’ve squared it with them, don’t you worry!’ (Of course he hasn’t.)

‘I’ll send a car to pick you up after school, and your sister and little brothers. You can move in straightaway.’

My brother, Bob, holds out for a while, loyal to Mimmy, my mother’s mother, and even to my stepfather, Larry, whom he had reviled when my mother was alive. But he knows it’s hopeless, and anyway, sharing a house with Uncle Tom seems like a better proposition than living with our exhausted stepfather and our frail and crotchety grandma.

Our new house is a lovely shingle affair with a porch. It’s located on one of the prettier streets behind the Presbyterian Church in town, not far from school. Uncle Tom indulges our every whim. Mine is that I want to be called Elizabeth, my middle name, instead of Mikey, named for my father’s favourite brother, Michael, who was struck down with polio at the age of nineteen. This is occasionally lengthened to Michael when my sister is angry with me.

Tom installs a kind black couple, George and Lessie-May, to look after us during the week – he’s working in the city weekdays – and so now we’re all set. But one of us is missing – my half-sister, Nanette, and although I have my own very nice room in a clean and ordered house, my little sister isn’t here. She’s only four and a half years old and she belongs to my stepfather, so he keeps her.

At weekends, Uncle Tom makes us do inkblot tests, ten little cards invented by someone called Rorschach. They remind me of the flash cards in kindergarten, with a picture of an apple, or a dog, where you have to say what it is. This time, there are shapes – blobby and symmetrical.

‘Tell me what you see,’ says Tom.

Is this a trick question?

‘Rabbits, twin baby elephants, an angel, butterflies. Gosh, maybe a couple of Russian Cossacks… dancing wearing red hats.’

‘Good,’ says Tom.

He seems pleased with my answers. He appears pensive, sometimes a little surprised-looking, but there never seems to be a wrong answer. I like the Rorschach test better than the kindergarten flash cards. They’re more interesting.

The first thing Tom does to make his claim for custody more viable is quickly to marry a girlfriend of his, Joan Harvey. Joan is beautiful and funny and an actress. She stars in the popular TV soap, The Edge of Night. She devises ways of saying hello to us when she’s on TV.

One morning when she’s leaving for the city, she says, ‘Watch for me touching my right ear, that’ll mean I’m saying hi.’

We rush home from school, take our peanut butter and jelly sandwiches and glasses of milk to the living room, and scrutinize the television. Sure enough, at the given moment she gives the signal. We whoop with delight.

Uncle Tom has had a wealthy and privileged upbringing, but it’s also been conservative and religious. The boys were sent away to Benedictine boarding schools, my father to a Catholic military academy run by Jesuits, and the girls to the Convent of the Sacred Heart. My brother Bob, aged fifteen, is at the same military establishment and my sister spent a term at Kenwood, a Catholic boarding school in Albany, New York, before returning to our local high school. We three younger kids have so far escaped these types of schools, my mother opting instead for the local elementary. God only knows what my wealthy grandmother had in store for us.

My Uncle Tom wants us to have something better, in England, where we’ll be able to make a fresh start, leave the past behind and begin again.

The thing is, he isn’t coming with us.

When Uncle Tom shows up at Camp Waneta, I haven’t seen him for over a month. He takes us out to a diner in town. Acker Bilk’s ‘Stranger on the Shore’ is playing on the jukebox. The tune is the background melody to the summer; it seems to be playing wherever we go. I make up words, singing along to the plaintive clarinet solo in my head:

I don’t know why, I love you like I do;

I don’t know why I do; I do, I do I do.

The birds that sing their song,

Are singing just for you.

I don’t know why I love; I do, I do, I do.

Uncle Tom has a camera with him and wants to take photos of us. He gets us to pose, individually, not together like a happy family.

‘Deedee, can you stand over there, against the sky. I need you on a pale background. Good. Mikey, you next.’

I smile as best I can.

‘Well, kids, I guess that just about wraps it up for the time being. See you in a couple a weeks.’ And off he goes.

Sure enough, two weeks later, Uncle Tom comes to get us in a big station wagon. My Aunt Joan is with him. There’s lots of luggage in the back. There are five duffel bags, each with our names written in heavy marker pen on the straps. I’ve been looking forward to seeing my little sister Nanny, my Grandma Mimmy and my toys, but we don’t drive home like I expect. We drive straight to Idlewild airport and on to the plane.

As usual Uncle Tom is accompanied by an entourage of strange men. Seven of them have come to see him off. Saul, a grey-haired man who seems to be in charge, is giving Uncle Tom an injection. Standing on the runway, my uncle has his sleeve rolled up. He’s afraid of flying. So am I, but I’m afraid of injections too, so I keep quiet.

My uncle’s friends take turns to hug him and pat him on the back.

‘You can do it, Tommy, have courage,’ they say, which is puzzling, because we’re only going to England for a week.

Joan doesn’t come with us.

When I ask her what she will be doing, and won’t she be lonely without us, she says, ‘Don’t worry, I’ll stay home and play with myself.’

My older brothers and my sister laugh, as if she’s told a very funny joke. Then my Uncle Tom hands out our passports with the photos taken at Camp Waneta, against the pale blue sky.

In London, we stay in a little hotel off Leicester Square. We do a lot of sightseeing by taxi and throw water bombs from the fifth-floor window of the hotel. We go and see West Side Story at the Odeon, where a woman gives me a box of almost uneaten Maltesers. My sister teases me that they are poisoned. The little balls of chocolate roll around in their box temptingly, and in spite of the danger, I eat them all, waiting until one chosen chocolate sphere and its magical centre has melted on my tongue before putting a fearful hand inside the box to take another, and another.

And then, quite abruptly, the holiday is over.

The strange thing is we don’t go home.

My uncle takes me and my brothers Sean and Chrissy (twenty-three months younger than me) to a train station. I can just make out the letters over the entrance. Liverpool Street Station. A kind lady with a foreign accent meets us. My uncle shakes her hand and introduces us.

Tom says, ‘Don’t worry, I’ll be over to see you at Christmas. We’ll all be together then.’

We’ve already said goodbye to Bob and Deedee at the hotel; they are going to a school in Scotland, called Kilquhanity.

What a funny name, I think.

My sister says, ‘Don’t worry, Mikey, we’ll see each other on vacation, and I’ll write you a letter.’

I haven’t had a letter before.

My sister is quite excited. She finds the constant change kind of addictive. She’s thinking: This’ll be fun. My friends are going to be so jealous.

And yes, there is something exciting about this big adventure. But being shunted around, the secrecy, the unpredictability of it all has begun to wear a bit thin.

‘OK, kids, I want you to be good. Do what the lady tells you and run along with her, the porter has your luggage. He’ll take you to your carriage.’

Carriage as in Cinderella?

My uncle gives his slightly wry smile. He ruffles my brothers’ hair and kisses me on the forehead. The lady takes my hand. I’ve never been on a train before. I’m too excited to feel sad. There have been so many goodbyes anyway and there is probably something nice to look forward to at the end of this journey.

Uncle Tom waves until we are out of view. I put my calico dog up to the window so he can see out, and I get him to wave his paw. Sean is too defeated to fight this time. He is standing, leaning with his chin on his folded arms, against the window next to a sign that reads, ‘Do not lean out of the window.’

I feel sorry for him. There’s an ocean between him and his Little League baseball now. ‘Sean, be careful,’ I plead with him.

He sits down, heavily.

The engine and the steam and the noise lull us into silence. We look out of the window at the grey city going by and then we slow down as we cross a bridge, high above a little street of doll-like terraces, with front doors opening right onto the pavement. The bridge runs across the middle, dividing the street in half. The houses aren’t very far below and I can see a group of children playing hopscotch; others are skipping; a small child is riding a tricycle along the pavement. A mother stops to shield her eyes and look up at our train. It seems like she’s looking straight at me. I wave and the woman waves back. The children and the woman disappear from view as the train moves on, and I can see the backs of the houses now, washing on some of the lines, white sheets, and then big grey buildings, factories, and the train gets faster, faster and then I fall asleep.

When I wake up, there is green going past the window, and beyond, flat yellow fields and little square towers and lots of sky with frothy clouds that seem to mimic the green foliage. The kind lady with the foreign accent is knitting. I’m fascinated. She doesn’t knit like my granny Mimmy, with the right hand looping the wool over the left hand needle. She keeps the wool stretched tightly around her left forefinger, and stabbing the right-hand needle into the wool. Every once in a while she stops to count her stitches in a language I don’t understand.

‘Zwei, drei, vier, fünf, sechs.’

She’s very fast.

Chapter 2

‘Who’s that funny old man with the dog?’ I ask a freckle-faced girl who looks like she knows her way around.

I keep seeing a tall man in a brown corduroy jacket and baggy old man’s jeans, the kind that carpenters wear. On his feet are enormous shiny black lace-ups. He’s stooped and has a strange accent. I think he must be German.

He’s surrounded by a group of small children who are jumping up at him, shouting, ‘Neill! Neill!’

He looks down, keeping a lighted cigarette out of their way.

‘You, you and you, go and find me a great big man with white hair who’s been seen wandering around the school. He’s an awfully nice-looking chap!’

‘It’s you! It’s you! You’re the man with the white hair!’ they all shout, laughing excitedly.

Evie turns to me and smiles: ‘Oh, that’s Neill. This is his school.’

‘What, you mean he’s the principal?’

‘I guess, well, the headmaster, but not like a normal head. I mean, he doesn’t order us around or tell us what to do.’

‘So, does he just kind of hang around?’

‘I guess so. Sometimes he says things at the meeting, but he has to put his hand up and wait for the chairman to call his name before he can speak, like everyone else.’

‘Oh,’ I say, still a little puzzled.

I’m assigned a dormitory on the first floor, a big room with bare floorboards, and a rusty fire escape leading from one of the gabled windows at the side. There are five other girls: one American, three English, and one Norwegian. My new family consists of sixty kids and a few adults, mostly foreign, all displaced, trying to figure out how to live in Neill’s self-constructed, child-centred universe.

We sleep in old army bunks. The school had been evacuated during the war and taken over as an army HQ (given its proximity to the Suffolk coastline it’s perhaps unsurprising). The war is something remote and we’re not sure when it finished. It could’ve been last week for all we know. There are reminders everywhere: sandpits, bunkers, look-out posts on the beach at Sizewell. I hear people talking about something called rationing. I can’t imagine not being allowed sweets if you have the money to pay for them. Wooden huts with flat, corrugated iron roofs serve as classrooms and sleeping quarters for the staff. These are heated (unlike the big house) with fumy paraffin stoves, which we children huddle over as we scribble with ancient ballpoint pens, in equally ancient and mouldy exercise books (also army surplus).

I get a top bunk perhaps because I am tall and thin and can hoist myself up easily. Below me is Vicky Gregory, from Portland, Oregon. She has a big sister and a little brother here too. Vicky is loud and robust with a good sense of humour; she has what the English call a cheeky grin.

All our parents are absent, only mine are dead.

Vicky’s parents are psychiatrists: ‘My dad came to America from Russia when he was three on a passenger ship. His grandma looked like a Russian babushka, you know, with a shawl wrapped over her head, and a long dress. She couldn’t speak a word of English. My mom’s a Native American. She worked in a hospital that’s been written about in a book!’ (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest will be filmed a decade later.)

Next to our bunk a single bed will be added for Anna, who arrives from California the following term. A shy, pale, softly spoken girl with golden-coloured hair and a nagging cough.

On the other side of the room, in a top bunk, is Evie (with the freckles), an old-timer. She’s been at Summerhill since she was four. Evie is proud of her status and can always be relied upon to fill us in on school traditions.

‘Do you know how to play fuck-chase?’ is pretty much her first question to me.

I have difficulty imagining fuck-chase actually working. Little boys with their limp baby penises chasing little girls and then bumping up against them ineffectually. Perhaps the other way round, the girls chasing the boys, would be more viable.

‘We’re not a school-school,’ says Evie, parroting Neill’s speech made earlier that week. ‘We’re a community and we all have an equal say in how things are run. We can do whatever we like, as long as it doesn’t harm anyone.’

Apparently we have freedom, but we don’t have licence, whatever this means.

Eleanor from London sleeps on the bottom bunk; her little brother Hector is at the school too. She has dirty blonde hair held back with an increasingly grubby velvet headband, and round, pink, National Health specs. She speaks like the Queen with a pronounced upper-class accent, hangs out with the older boys, and is considered a bit of a swot.

Diagonal to their bunk is Hannah from Hammersmith. Hannah’s parents, Daphne and Robert, have sent her to several schools, including the French Lycée, and she still can’t read. Today, she would be diagnosed as dyslexic. In despair, her parents have sent her to Summerhill, where at least she’s happy. One day Hannah will become a renowned china restorer, but right now she is amazingly clumsy with the ‘wrong’ kind of hair, unfashionably curly and frizzy.

Hannah’s mother – who looks like a more chic version of Princess Margaret (big sunglasses, orange lipstick and a silk scarf tied fashionably behind her head) – sends weekly copies of Bunty and Judy. These are bagsied and passed around. Gosh, it’s awful being tenth in line, the comic tattered and out of date by the time it reaches you. Hannah’s parents also send expensive biscuits for her birthday, from Harrods – chocolate florentines, the chocolate too grown-up and bitter for us to gorge on, and glacéed chestnuts which are equally disgusting.

On the top bunk, above Hannah, is Vaar from Norway. Vaar is the exotic one. Her mother, an African American, is an opera singer and sang in the first ever production of Porgy and Bess. She was the first African American to study at the Julliard School, but gave up her career in America to marry a Norwegian skiing champion. Vaar has black, curly hair and almond eyes. She can climb trees like a monkey and mostly hangs out with the boys. She wears Norwegian sweaters patterned with snowflakes, and ski pants, but she also wears a black leather jacket when she’s tree climbing, which gives her a boyish edge. Her parents send her parcels with amber-coloured cheese, which she cuts with a special cheese knife. Shaving thin, semi-transparent slices from the block, she hands out slivers, like sweets.

Lying in our beds in the dark, away from our families, we talk about home.

Evie brags about her mother Myrtle:

‘She once appeared on a TV programme called Six-Five Special with her skiffle group. Dad doesn’t live with us. He’s a famous actor. He’s with the RSC, and he’s been in Ealing Comedies.’

I don’t ask what they are.

‘Tell us about your mom.’ Vicky’s voice rises up through the dark.

‘Oh,’ I hesitate, feeling my way into Mom’s room. ‘She had so many dresses. I guess my favourite was the black and orange one with a black velvet bodice and a skirt and collar in orange silk…’

I run my fingers over the fabric on the skirt as Mom busies herself with her stockings. I watch her fish out an unladdered pair from the scramble of froth in her underwear drawer, and attach them to the stubby and exhausted-looking straps that dangle from the bottom of the girdle.

‘Can I look in your jewellery box?’ I ask her.

She passes it over. I pull out long strands of beads and untangle them. Matching up her earrings, I lay them out on the counterpane.

Mom is getting dressed. She is wearing a strange undergarment, a Playtex Living Girdle. It isn’t actually alive, but apparently it breathes. The girdle, coupled with her Playtex Living Bra, to keep her saggy breasts pert and pointing forward, makes her look like a slightly under-done mermaid. The ribbed white fabric of the girdle, with its diamond shape panel of satin at the front, starts at her ribs, finishing at the tops of her thighs.

‘Good grief, I can’t believe the time,’ says Mom.

It’s late afternoon and people are coming over for cocktails. Mom is going to wear one of her hostess gowns, which button down the front so you don’t need to wait for your husband to come home from work to help you with the zip. Mom has a collection of hostess gowns. They combine the glamour of a cocktail dress with the practicality of a housecoat. Somehow Mom always manages to look classy. It doesn’t matter if the dress comes from Saks Fifth Avenue or John’s Bargain Store. Everything looks good on her. And she still has some nice jewellery left over from when we were rich and she was married to my father.

‘Then what?’ says Vaar.

My mind skips forward to the time when my stepfather locked my mother in the bedroom and poured all the booze down the toilet. In revenge or desperation, Mom drank the bottle of Chanel No. 5 that was sitting on her dressing table.

‘Mom and Larry once had this awful fight. Mom stormed out and we drove to Montauk. Just the two of us,’ I say.

What bliss to have her all to myself, just this once. To have the front seat where I can play with the cigarette lighter; pushing it in on the dashboard so that, when you pull it out, the end is glowing a bright red, coiled circle. Driving the five miles into town, most of the countryside is flat, but there is a hilly road that Mom speeds up for. It makes my tummy flip with excitement. The Roller Coaster Road, we call it.

Usually, the Packard is stuffed with kids. Without warning, Mom will turn and swat us with her free hand.

‘Stop your squabbling.’

We’re in town, in the car park outside Bohack’s grocery store, and she is trying to get Sean into the car. He wants to stay and play baseball with his friend Davey Crockett and my mother is swatting him, and missing. She’s slurring her words, shouting: ‘Get in the God darn car, Sean.’

People are looking at us. I’m embarrassed. I want her to stop.

‘Stop it. Just stop it, you drunken fucking bastard!’

My mother does stop. So does my brother. He looks at me:

You are in so much trouble, Mikey. More trouble than me.

My mother gets everyone into the car – well, Sean and Chrissy, my little sister, all the groceries in their brown paper bags – and she drives off without me. I’m left, standing in the middle of the car park. I wait a little while to see if she will turn around and come and get me. Surely she’ll turn around. I’m only eight years old. Surely she wouldn’t leave a child on her own to walk home? There is no sign of the Packard; I know the way home, and I start walking. I walk past the brown shingled Methodist Church, past Herb McCarthy’s Bar and Grill, past the road to the railway station, until I reach the edge of town – no houses, and just a grass verge with a fork in the road. I’m not entirely sure of the way now; I guess I just have to keep walking, straight ahead. Soon, some neighbours – the Johnsons who live nearby – stop in their car and give me a lift.

My brothers are in the living room, watching the Howdy Doody show on television. There’s no sign of Mom. I go upstairs to her room. The curtains are closed. She doesn’t tell me off because she is lying on her bed, crying like a little girl.

I stand there: ‘Mommy. I’m sorry, Mommy, I didn’t mean it. I’m sorry I swore at you, Mommy.’

‘You’re right, Michael, I AM a drunk. But “fucking bastard”. How COULD you? Don’t you know a fucking bastard is the most beautiful thing in the world? Don’t you ever forget that,’ she says through angry tears.

I wish I could undo my words. I’m trying to work out whether she’s angry about the swearing or the misuse of fucking bastard. I’m confused. She’s still crying. The bed is shaking with her sobs.

‘Can I get you anything, Mommy?’ I wish there was something I could get her.

‘No, dear, I’ll be all right. I just need a few minutes to myself.’

Sure enough, pretty soon she has her apron on and she’s in the kitchen, clattering pots and pans, as she cooks spaghetti sauce for dinner. Our favourite.

Communal living, after six weeks of Camp Waneta, doesn’t seem that strange to me. Perhaps I’m in a state of shock. During our first few weeks, Chrissy and I play on a deserted bit of land just outside the school perimeter. It’s an old army manoeuvre area with sweet-smelling gorse bushes dotted about in the sandy soil. We wander through it, eyes squinting in the darkening afternoon, searching.

‘Mom?’

We run after her, but her ghost eludes us, disappearing into the shadows.

That night my mother suddenly appears at the school to collect us in the Packard.

‘It’s all been a terrible mistake,’ she says, climbing out of the car, unscathed, to gather us into her arms.

She hasn’t died after all, and no, this isn’t a dream, I am actually awake – this is real.

And then I wake up.

Chrissy and I spend a lot of time sitting on the wall that marks the boundary of the school, ‘Summerhill’ painted along it in plain white capitals. We’ve heard the grown-ups talking about the Cuban missile crisis. Something is being decided back home, battled out between our President and Khrushchev, but no one tells us anything. We sit, gazing out at the gravel drive, wondering if we’re all about to die, far away from home, exiled on this cold island of damp crisps and salad cream. I have no urge to run away. I’m just waiting for someone to show up.

We begin to make our own friends. I only see my brothers at mealtimes or in the Saturday General Meetings. The General Meeting is where grievances, petty and grave, are aired. For a ‘free’ school, where children can do what they like, there are a lot of rules. Pages of them, all written by the school council and pinned to the notice board on one of the panelled walls in the lounge.

I try my best to be kind to Sean whenever I bump into him.

‘Hi Seanie, how’re things?’

‘Crap. I’m just waiting to get thrown out of this place so they can send me home’

I have a feeling home doesn’t exist anymore, this is it, but I don’t want to disillusion him.

‘Really? But you haven’t done anything really bad.’

I miss Deedee with her dark hair and deep brown eyes. Perhaps if Deedee were with us, things would be different. At school in America, she protected me from the bullies who threw their sneakers from the top of the changing room door, and the girl at Camp Waneta who made me cry. She was good at telling my brothers off too. But torn apart, we have to create our own little worlds, overseen by our respective housemothers.

The housemothers each have their own group of similarly aged children. They look after our practical needs and give the little ones a cuddle when they are feeling homesick. Once a week they present us with a neat pile of ironed clothing with our name tags sewn inside: vest, pants, jeans (increasingly patched), a shirt and pyjamas.

Sean has Olly (real name Daphne Oliver) who is fat and jolly and plays the trombone. She dresses in men’s clothing, usually a plaid shirt and carpenter’s jeans, has short black hair, highlighted with grey as the years go by, and apple-red cheeks. She laughs a lot, in a way that’s almost like crying, with her eyes completely closed. She runs the school jazz band. They play ‘trad’ jazz because that’s what she loves. Her hero is someone called Kid Ory. Chrissy will soon come to play the tea-chest bass quite convincingly; he really puts his heart into it.

Chrissy has a succession of house mothers, before he moves up to Olly and ‘the Carriages’ (a separate building made from old railway carriages, huddled around a coal burner). Luckily for me, I’m handed over to the foreign lady who met us at the train station in London. I don’t know it yet, but Ulla will become the centre of my world.

Chapter 3

I wonder why I didn’t see this coming. I mean, only a few months ago, I was at my Uncle’s place in New York with Deedee who was lying on the couch, reading a book.

‘What are you reading?’

She flashes the cover: Summerhill: A Radical Approach to Child Rearing by A.S. Neill.

‘It’s about a school in England.’

‘What’s that?’

‘A free school. You can do what you like. The kids run the school and you don’t have to go to classes if you don’t want to.’

‘Is that good?’

‘Listen to this,’ she says to her boyfriend (her feet are on his lap). “Sex with love is the greatest pleasure in the world, and it is repressed because it is the greatest pleasure.”’

She looks at him significantly.

Doug is older than my sister. He’s interested in the Beat poets and has even been to Europe. The idea of a ‘free school’ appeals to them both. They’ve recently returned from a trip to Greenwich Village where they mingled with the beatniks in Washington Square, wearing dark glasses and blue jeans.

She goes on flicking through the pages: ‘“Punishment is an act of hate. Summerhill is possibly the happiest school in the world. I seldom hear a child cry, because children who are free have much less hate to express than children who are downtrodden. At Summerhill we treat children as equals. Each member of the teaching staff and each child, regardless of his age, has one vote.”’

‘Cool,’ says Doug.