18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

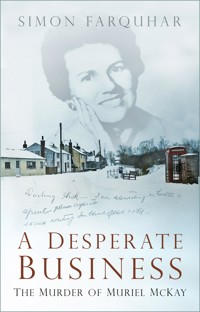

'Simon Farquhar succeeds brilliantly (and with real empathy for all concerned) in setting the story in its historical, social and emotional context, with the victim and her family always at the heart of his writing … A Desperate Business is an absolute must-read.' - Carol Ann Lee, the bestselling author of The Murders at White House Farm Winter 1969. Rupert Murdoch, newly arrived in Britain, has bought The Sun and the News of the World, immediately provoking outrage by serialising the sensational memoirs of Christine Keeler. Watching him being interviewed on television, two men hatch a plot to kidnap Murdoch's wife for a million-pound ransom. But the plan goes wrong. Following Murdoch's Rolls-Royce to a house in Wimbledon, they are unaware that he has gone to Australia for Christmas and loaned the car to his friend and colleague, Alick McKay. On Monday, 29 December 1969, Alick arrives home to find his wife, Muriel, has vanished. She was never seen again. Acclaimed author and journalist Simon Farquhar has spent three years investigating one of the most frightening and perplexing mysteries in British criminal history, which began with a case of mistaken identity and led to one of the first convictions for murder without a body being found. Presenting a wealth of new information and, for the first time, a possible solution, A Desperate Business is a meticulous and sensitive account of a tragedy. It is a story of greed, unimaginable cruelty, and newspaper rivalry, but most of all, the story of an adored woman who never came home.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Praise for A Desperate Business

A Desperate Business is a brilliant piece of investigative journalism and a true crime masterpiece. Farquhar’s book is forensically researched, his storytelling propulsive and gripping. In his re-examination of the case, he tries to provide answers to lingering questions, chiefly: where was Muriel McKay’s body hidden? This might be a 50-year-old landmark case, but the themes still resonate today: a police force struggling to crack the case, a salivating Press and a female victim cruelly used as a pawn in a tawdry circulation war.

Jeremy Craddock,author of The Jigsaw Murders

This is utterly gripping from the first page, and the complex and delicate subject matter is handled deftly and sensitively. It is an extraordinary feat of research too, but what is perhaps most impressive is how the book straddles the genres of true crime and social history. As well as shining new light on what remains a compelling mystery (and one which seemed destined to remain in the shadows), Simon Farquhar evokes a Britain that is distinctly familiar even as it rapidly slips into the rear-view mirror. A Desperate Business is the sort of book that I read with delight combined with a tinge of envy at how good it is.

Daniel Smith,author of The Peer and the Gangster

It was a case I had wondered about researching myself with a view to writing a book, but I’m very glad that I didn’t, because Simon Farquhar was clearly the person for the task. The case itself is unremittingly harrowing, complex and frustrating, not least because the much-loved Muriel McKay remains unfound. Nonetheless, Simon succeeds brilliantly (and with real empathy for all concerned) in setting the story in its historical, social and emotional context, with the victim and her family always at the heart of his writing. I hope one day he will be called upon to write a new epilogue, when Muriel McKay is laid to rest, but until then for anyone interested in the case and in that period of British history too, which is brought vividly to life, A Desperate Business is an absolute must-read.

Carol Ann Lee,bestselling author of The Murders at White House Farm

With special thanks to the McKay family for the use of photographs.

Every effort has been made to identify copyright holders and obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. If any omissions have occurred, please get in touch with the publisher for corrections to be made in future reprints and editions.

First published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Simon Farquhar, 2022

The right of Simon Farquhar to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-8039-9145-0

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

For my Mum

and in memory ofMuriel Frieda McKay

CONTENTS

Preface

A Note on Money

1 Home

2 Paper Tigers

3 Desperation

4 Advent

5 Trespasses

6 Ruins

7 Voices

8 Whispers

9 Silence

10 Epiphany

11 Paper Flowers

12 Paper Chase

13 Disconnect

14 Midwinter

15 Evidence

16 Judgement

17 Echoes

18 Legacy

19 Conclusions

20 Last Resort

Afterword

References

Index

PREFACE

My introduction to this dreadful story came through my father, a dedicated police officer, a fine detective and a very great man. When I was a teenager, he became newsworthy for having secured a conviction for murder without a body being found, in an appalling case of a teenage girl who had been abused and ultimately murdered by her stepfather. While securing a conviction for murder without a body was not unique, it was unusual, and it naturally evoked memories of the tragedy of Muriel McKay, which had taken place sixteen years earlier. I was inspired to ask him about it, and he told me the brief facts of a case which remains both heartbreaking and mystifying.

Sometime later, I read the concise account of the case in Gordon Honeycombe’s Murders of the Black Museum. Who can say why one story will possess or obsess a person, but even today I can still see, beyond this sea of research, those early images that my mind created of this case: the dark, wintry countryside on the Hertfordshire–Essex border (an area that I knew well and close to where I grew up); that spartan farmhouse; the isolated telephone boxes from which those dreadful calls were made, some eerily cold, some brutally hot-tempered; and, above all, the image of an adored woman, reading the newspaper on a December evening, the warmth of the fire inside, the promise of snow outside, whose life was turned in an instant from comfort to horror.

In the decades since first becoming acquainted with the case, it continually tugged at me that while Nizamodeen Hosein was still alive, while many of those involved in the case were still alive, there was surely some hope of finding some answers. Half a century on, it felt, at the very least, a duty to history to capture what I could. I imagined someone twenty years in the future questioning why no one had revisited the case while there were still living witnesses and a living perpetrator, as crime historians now wish had been done in other cases that continue to perplex, from the Rillington Place murders to the mystery of Jack the Ripper.

The opportunity finally presented itself when my comissioning editor, Mark Beynon, requested a follow-up to my book, A Dangerous Place: The Story of the Railway Murders. Since no book had been written on the McKay case for forty years – the ones that had been were all long out of print – and the case was now being mostly misrepresented in documentaries, magazines and blogs revelling in gruesome theories and showing scant regard for facts, I suggested a new study, only to find that another book had just been commissioned on the subject. That book was subsequently abandoned due to a lack of new information, but I too felt that it would be hard to justify a new book that merely regurgitated the established facts and assumptions.

However, when some of the long-closed police files were opened, the wealth of previously unpublished information held within them cast a powerful new light on the origins of the crime. This convinced me that there was a new story here that should be told. I also traced the current whereabouts of Nizamodeen Hosein, although it never felt a very real possibility that I would one day be able to put my questions to him.

I was extremely wary of approaching the McKay family, since they had made no public appearances in connection with the case since 1970 and I had no clue as to whether they were still searching for answers or had managed to lock their tragedy away. I decided that I would not pester them with my questions unless I could offer some answers to theirs.

There have been challenges along the way, not least the closure of archives and libraries during the coronavirus pandemic, and the navigation of the arcane world of Freedom of Information Act (FOI) requests. When Britain entered its first lockdown, with my research well under way, I decided to use that time while the National Archives were closed to visitors to submit a request for access to those files which remain closed until 2062. The request was refused, but to my horror, it also resulted in a decision to reclose all open files on the case. Although I had already had considerable use of them, it would have wrecked any hopes of this book being a comprehensive one.

Challenging the decision was a process that took months, and was mostly conducted by email, since I was told that the FOI assessors ‘were not taking telephone enquiries during the pandemic’. Finally, with certain necessary redactions, I was granted access to the material that I needed, but the whole affair, and the current obstructions and contradictions that the McKay family are facing in their quest to have the remaining files on the case reopened, have left me firmly of the belief that while the principles of the FOI are commendable, on a practical level it is in desperate need of revision.

A puzzle set by fools can be harder to crack than one set by a genius. At the end of a three-year journey, during which time the case has also been revisited by the police and the world’s media, I hope that this account – a personal journey through a dreadful history – offers new information, new insights and even, perhaps, a solution.

Throughout the text, generally only primary documents are quoted without caution. Nothing claimed by the Hosein brothers (including Adam) should be considered trustworthy by itself. I regret having to use the brothers’ first names throughout, something necessitated by them sharing a surname but which inevitably risks softening the presentation of them.

This book travels back to a distant and very different Britain, populated by pubs that no longer survive and no longer could survive, pubs where farmers struck lunchtime cattle deals. It was a quaint age populated by people with occupations that also no longer survive, from buttonhole makers to bread roundsmen, but it was also a pre-#MeToo era of relentless sexual harassment, a dimension to the story that has not been previously explored.

Both Arthur and Nizamodeen Hosein have used racial prejudice as a smokescreen for their guilt, to elicit sympathy or to apportion blame. However, while race relations in Britain were in a sorrowful state at this time, they have little relevance to this story. I have found barely any evidence, among the statements of the residents of Stocking Pelham or the tailors of the East End, that racism was a factor of any significance to the murder of Muriel McKay.

This is not complacency, but a simple refusal to allow convicted murderers to control a narrative and to exploit one of society’s most serious problems to their own advantage. The only consistent and wilful racism I could find in this story came from Arthur Hosein, whose clear antisemitism climaxed with his outrageous attack on the trial judge.

While modern Britain continues to struggle to combat racism, it has become sterner at monitoring the language that it uses. The past is often inconvenient, frequently embarrassing and sometimes shameful, but we cannot change it and we cannot destroy it. We can only try to understand it. Therefore, where necessary, the language of those times has been retained. While we may wince at the mislabelling of Indo-Trinidadians as ‘Pakistani’ and at the use of the term ‘coloured’ today (it was used readily by people of colour at this time), I hope that the reluctance to replace these terms retains historical accuracy without causing contemporary offence.

I have strived to keep Muriel McKay at the centre of this account. When combing the files, I discovered a bundle of postcards that were collected by the police to provide handwriting comparisons with the letters that were written by Muriel during her captivity. These postcards had been sent to her housekeeper, Mrs Nightingale, over a twelve-year period, the last one dating from just a few weeks before Muriel’s abduction. While picture postcards will never be the most profound expression of a personality, they do provide a kind and sensitive impression of Muriel McKay, and quoting from them has allowed me to begin each chapter with her voice.

Above all others, my sincere thanks go to the McKay family, for their hospitality and warmth, and for placing their trust in me. I am also most grateful to The History Press, particularly my commissioning editor, Mark Beynon, for his devotion to this project from its very beginnings.

So many people gave up their time to assist in my research, and I extend my deepest thanks to Walter Whyte, Roger Street, Peter Rimmer, Des Hiller, Paul Dockley, Brian Roberts, Peter Miller, Roy Herridge, Paul Bickley, Ewan and Nicky Gilmour, Chloe Baveystock, Aubrey Rose, Professor Patricia Wiltshire, Freida Hosein, Yasmin Strube, Sharly Hughes, Martin Rosenbaum, Jeff Edwards, Norie Miles, Matthew Gayle, Clive Stafford Smith, Jill Murray, Tom Mangold, Leela Ramdeen, Dr Dominic Watt, Don Jordan, David Cowler, William Stevens, David and Marion Ryan, Colin Parker, Tom May, Michelle Bowden and Holly Kennings of the Solicitors Regulation Authority, Sarah Nithsdale of HMP Wakefield, Abigail Leckebusch of the West Yorkshire Archive Service, Hertfordshire Archives and Local Studies Library, the Law Society, the Metropolitan Police, the Metropolitan Police History Society, the General Register Office, the office of Manor Park Cemetery and Crematorium, the staff of the British Library, especially Nicola Beech, the staff of the National Archives and Freedom of Information, Equity, Merton Heritage and Local Studies Centre, George Hardwick of Clacton Local History Society, Clacton Library, Andrew Frost of John Frost Newspapers, Luke O’Shea of the BBC Photo Library, Nicholas Mays of the News UK Archive, Hertfordshire Coroner Service, Andrew Wood of the Telecommunications Heritage Group, Austin Graham of the Grosvenor Victoria Casino, Park View Care Home, and Lindsay Ould and the staff of the Museum of Croydon.

On a personal note, I thank Naomi Harvey, Andrew Conway, Mark Nickol, Nick Kirby, Keith Skinner, Lindsay Siviter, Ian Greaves, Chris Croucher, Sue Scott, David Wigram, Alex Paltos, Joey Langer, Tinamaria Fairbrass, Julie Peacock, Natalie Froome and Jules Porter, and finally, Suzy Robinson, Sarah David and Debra Sergeant for their unfailing enthusiasm and support.

Simon FarquharLondonSeptember 2022

A NOTE ON MONEY

Money – and the love of it – is a key ingredient of this story. The preposterousness of the £1 million ransom demanded by the Hoseins, compared with the everyday cost of living in 1969, may not be immediately apparent today, when far greater sums are regularly won on the National Lottery. At necessary points in the narrative, I have noted the amounts translated into today’s money, taking into account that money has inflated at 1,554 per cent in Britain since 1969.1

The Bank of England’s inflation calculator translates £1 million in 1969 as £17.5 million in 2022. However, this is an oversimplification of the amount in real terms. Attitudes to money, spending habits and the valuation of different items have changed in many ways over the last half-century. Food, clothes, appliances and holidays are more affordable today, while wages for men have remained reasonably steady and the costs of alcohol, housing and live entertainment have increased dramatically.

The average full-time (male) worker was paid £30 a week in 1969, an annual wage of £1,560, which is £24,050 in today’s money, compared with the average full-time wage today of £31,834. However, the average house price was £4,312, a mere £71,333 in today’s money, whereas the average house price today is £215,910. Conversely, a loaf of bread was three times more expensive then than it is today, most working-class people could not afford to holiday abroad and renting a colour television from Radio Rentals cost £1 a week, which amounts to £865 a year in today’s terms.

What is perhaps most important to remember is that there was a much clearer financial divide in economic terms in Britain in 1969. Many items that were seen as luxuries then are affordable treats today, and there were far fewer opportunities then for extensive credit. People were more inclined to live within their means. Most people were paid in cash, and bank accounts were far from being essential.

Living above one’s means in 1969 was a far more transgressive activity than it is considered today.

1

HOME

The first evening we had a dinner party out on the terrace for twelve (David’s birthday). It was a lovely mild evening, no jackets needed. Dancing on the terrace until 2am.

Muriel McKay, Calader, Mallorca, 9 September 1969.

Christmas descends again, a season of enchantment and disillusion, anticipation and mourning, prettiness and sadness. I am standing outside St Mary House, on Arthur Road in Wimbledon village. It is approaching six o’clock in the evening. Across London, white winter sunshine is handing over to the night shift of headlights and fairy lights. It is almost precisely half a century since this fine, cherished house, in this safe and stately realm, which was then home to the McKay family, became a scene of atrocity and despair.

On 29 December 1969, sometime between 5.30 p.m. and 7.45 p.m., between driving her housekeeper home and her husband returning from work, Muriel Frieda McKay had her home invaded and her life devastated. She was never seen again. We will never know for certain the precise details of what happened that evening, nor the precise details of the torturous events which followed.

Christmas delivers prettiness and sadness, and so too, for the last fifty years, have the few photographs that the world has seen of Muriel McKay. Once images of happiness, they are now images of anguish. Happy photographs from carefree, happy times, like the carefree, happy words on picture postcards, develop a poignancy and a pathos when the lives that they remain souvenirs of are no more.

Like so many of the victims of extraordinary or infamous crimes, this blameless woman is remembered for her death and not for her life. Her name has been remembered more than that of many victims, since to a country that became obsessed with the story, she was a missing person, and the first victim of kidnapping-for-ransom in Britain since the Middle Ages, long before she was declared a victim of murder and her killers identified. Her name and her image endure because of the continuing, perplexing question of what exactly happened to her, and where her body may lie, and her story remains one of the most tragic and outlandish mysteries of modern criminal history.

Some months later, on a bright afternoon, I am making a return visit to Arthur Road, where the charming owners of St Mary House today have allowed me to visit the scene of modern Britain’s first-ever kidnapping. As I walk up the hill to the village and away from the hurry-scurry of the station and the shops, life becomes noticeably quieter and more expensive. Two girls, meeting outside a pub for the first time since lockdown, joking that they are both still alive, greet each other with noisy delight, brimming with life and unmindful of the vicious tragedy that began nearby and which, for the McKay family, continues to this day.

Wimbledon village today is as charming as it was half a century ago, but considerably more costly. The shops that Muriel visited on her last afternoon of normality have long since regenerated, but still that attractive blend of locality and quality exists when one wanders the parade of butchers, boutiques and bistros. One is also struck by the diversity of the neighbourhood. This is a very different Britain to the one that so embittered Arthur Hosein – a Britain still far from perfect, a Britain not so naive and not so happy, but perhaps a Britain progressing.

After two years of studying newsreels, police files and press coverage, walking up the drive of St Mary House stirs a strange trepidation and déjà vu. It is always odd surveying a scene that one has been used to seeing on film. Unlike the world around it, the house has changed little since the days when it was immortalised in forensic photographs and tabloid splashes. The welcoming red-brick neo-Georgian home is set 10 yards back from the road and given partial privacy by a fence and hedgerow, though from the pavement one can clearly see the front porchway, as Mrs Mona Lillian could when she walked past on 29 December 1969 at 6 p.m. and saw a dark saloon parked in the drive while, inside, history was being made and lives destroyed.1

Inside, it is a happy, placid place, its owners blessed with good taste without ostentation. Pausing in the porchway, I wonder again just what did happen on that dreadful evening so long ago. Alick McKay arrived home to find that, uncharacteristically, the chain was off the porch door and the inner door had been forced open. A tangled band of Elastoplast lay on the hall table, and on the bureau immediately to the right of the door lay a brutal, rusted chopper, the telephone was upturned on the floor, its cord ripped from the wall and the smashed dial robbed of the paper disc containing the number, Wimbledon 01-946-2656.

Although where the story ended remains a mystery, how it began will also forever be uncertain. Why was the chain not on the outer door, when Muriel was always so particular about keeping it on when she was alone in the house? Peter Rimmer, one of the few surviving CID officers who worked on the case, reflects, ‘This was always the great question. How did they get her away from the house and how did they gain entry?’2

The inner door had been forced by bodily pressure. Had Muriel refused to open it, or had she opened it and then panicked and tried to close it again? Was one of her kidnappers holding the Elastoplast, ready to silence her, only for it to self-adhere in the ensuing struggle? Just why was the chain off the outer door?

Despite its grim antecedents, this hallway hosts no ghosts today. This is still a happy home, the lemon colours outshining the sweet pastel shades that the McKays chose. Structurally it is virtually unchanged, and the mood of the place makes it obvious why the McKays adored this house and why they lived here for a dozen contented years, its bright spell not even broken when they were the victims of a burglary in September 1969.

The hallway opens on to the square living room, immediately recognisable as the scene of the television appeals in which Alick, flanked by his family, exhaustedly pleaded for his wife’s abductors to contact him. Off the living room is the snug, the room where Muriel settled by the fire with a cup of tea, the evening newspaper and Carl, her beloved 7-year-old dachshund, in her last moments of comfort and joy. How someone can be nestled in the safety of their own home and then seconds later be snatched away and plunged into darkness remains, for me, the most persistent horror of this story. Yet today, again, this is a room with no sorrow, no echo of tragedy.

The kitchen – where Muriel sat having coffee with her housekeeper, Mrs Nightingale, just hours before her abduction, where the McKay daughters, Dianne and Jennifer, catered for the constant police presence in the weeks following the kidnapping, and where Detective Sergeant Walter Whyte listened in on the telephone extension early the following morning and transcribed the first of the sinister calls from a man calling himself ‘M3’ – looks out on to the wide, grassy garden, which was then tended to by Leslie Galashan every Saturday and Sunday morning, for whom Muriel had made a warming cup of tea the previous day. Off the kitchen, past a back staircase which would once have led to the staff quarters, is the only corner of the house to have undergone any structural alteration, with what was once the garage now converted into an extra room. The windows are barred, not because of the house’s history but because of another burglary some years ago, not that even these would have saved Muriel’s life.

I am curious as to whether potential buyers of a house with an unhappy history are told about it before purchasing, and in this instance, they certainly were not. Ewen Gilmour, the current owner, says:

My wife and I bought the house in 1985 from the Baveystocks, who in turn had bought it from Alick McKay. A few months after moving in, a neighbour happened to ask if what had happened here bothered us at all. That was how we found out. I was pretty aware of the story, which was huge when I was at school, but as we didn’t come from Wimbledon, for us it was history rather than anything personal. That said, memories in Wimbledon fifteen years on were still fairly fresh, and taxi drivers taking me home would often say: ‘Is that the house?’3

Returning to the hall, we ascend the main staircase, down which the contents of Muriel’s handbag were once scattered, and at the end of the landing, I discover the master bedroom. The layout is identical to that in the crime scene photographs, in which one also notices a Sunday colour supplement and a handsome edition of Shaw’s Prefaces, as well as a drawer left open, from which Muriel’s jewellery was snatched. Suddenly and overwhelmingly, for the first time in this peaceful place, I feel the anticipated sense of intrusion and fear.

The impression of those cruel strangers invading this private space and wresting treasured jewellery from the drawer is a vivid one. But there is another, even more persistent mood for one who stands here reliving this story. For it was in this room, one cold January morning, that Detective Chief Superintendent Bill Smith sat with a broken Alick McKay and told him that he would probably never see his wife again, putting his arm around him as he cried. Two eminent men of an uncrying generation, one weeping, one comforting him.

On 4 December 1969, Alick McKay came out of a reluctant retirement, at the personal invitation of Rupert Murdoch, to begin working at Murdoch’s newly acquired News of the World newspaper. The McKays saw ahead of them a Christmas with their children and grandchildren and a prosperous new year. Within three months, however, Alick McKay was gone from St Mary House, living alone in a small central London flat, his family fractured by tragedy and surrounded everywhere by the absence of his wife.

Although Muriel’s death has been endlessly speculated on, hardly anything of the person she was or the life she lived has ever been set down. Even Norman Lucas’s respectable account of the story, published a few months after the case was over, opened with a biography of Muriel’s husband rather than of Muriel herself. However, while Muriel McKay devoted her life to being a wife and mother and did not have a professional career by which to record her achievements, that is no reason to allow her presence to drift from the centre of any account of her tragedy. She should be remembered for her life as much as for her death.

Graced with a kindly beauty, Muriel came into the world as Muriel Frieda Searcy. She was born into an Australian family with long-standing legal and seafaring connections on 4 February 1914, the youngest child of Charles and Freida Searcy, and was raised with her brother and three sisters in Durham Terrace, in the suburb of Cheltenham, Adelaide. Her father, an executive in the motor industry, was one of fourteen children born to Arthur Searcy, President of the Public Service, Deputy Commissioner of Taxes and Stamps, Controller of Harbours and President of the Marine Board of South Australia, after whom Searcy Bay in the Eyre Peninsula was named. Arthur’s father, William, had been Chief Inspector of Police in South Australia and alongside his maritime achievements, Arthur was also a Justice of the Peace. Muriel inherited from her grandfather a talent for photography; to this day, William’s vast archive of nearly 20,000 photographs, along with twenty volumes of reminiscences and 3 metres of scrapbooks, the Searcy Collection, can be viewed in the State Library of South Australia. His granddaughter was also a talented artist; when she was 12, Muriel passed Grade II Freehand Drawing at the South Australian School of Arts and Crafts.4

The Searcys’ neighbours were a family named McKay, the children attending Sunday school with Muriel. Through them, she was introduced to their cousin, Alick. Like Muriel, he was tall, dark and handsome, and although five years her senior, and state educated, unlike her, their shared times at church and club dances led to love. In the forty years between their first meeting in 1929 and Muriel’s disappearance in 1969, the couple were never apart.

When she was 14, Muriel was admired in the local press as a bridesmaid at the wedding of her sister, Doreen. She wore pink floral taffeta and georgette, early Victorian style, and carried a bouquet in lavender shades. She and her sister Helen wore tulle caps, trimmed with coloured sequins. The church was decorated by the congregation, among whom were Alick and his parents.5

She was remarked upon again two years later, dancing to a blues band at Kalleema Dance Club at the Maris Palais in Semaphore.6 Statuesque, green-eyed and winsome, she was later described by her husband as ‘the quietest, most charitable person’7 and by her daughter, Dianne, as ‘so gentle, so kind, lovely and hospitable, she could never see the bad in anyone’.8 Family friend Lady Jodi Cudlipp, wife of Hugh Cudlipp, journalist and Chairman of the Mirror Group, called her ‘a lovely woman. She was always a friendly, charming, good-looking, nice lady.’9

Upon leaving school, Muriel worked as a stenographer. Although she was offered an art scholarship, she opted for the expected role of wife and mother, though she never neglected her talents. As well as a number of tapestries, the product of her love for needlework, the house at Wimbledon was plentifully decorated with her paintings, both watercolours and still lifes in oils, and with her photography. On the day of her abduction, she told Mrs Nightingale that she had just enrolled in a new painting class. That night, when Alick arrived home, amid the puzzling wreckage, he found a smashed flashbulb in the porch, which had probably come from his wife’s handbag, part of her photography kit.

Muriel became engaged to Alick when she was 18 and they married when she was 21 on 15 June 1935, at St Peter’s Church, Glenelg.10 Their first child, Jennifer Louise, was born two years later, followed by Dianne Muriel in 1940 and Ian Alexander in 1942.

Meanwhile, Alick’s career was gathering pace. The fourth son of Captain George Hugh McKay and Agnes Fotheringham Miller, he was born at their home on Tapley Hill Road, near Port Adelaide, on 5 August 1909. His father was a master mariner for the Coast Steamship Company, later master of HMAS Warrawee. His expert handling of that ship on one occasion prompted passengers to write to the Coast Steamship Company, commending ‘the skilful manner in which he handled the steamer and turned it around in the raging storm’.11 Like the Searcy family, whom they had a long association with, the McKays were impressive members of the community, respected for generations of nautical expertise and for being key players in the development of coastal trade in the region.

Alick and his siblings, however, would ultimately excel in the corporate world, with interests in timber, tobacco and newspapers. Alick was educated first at Alberton School, then at 16 spent a year at Thebarton Technical School. Like his younger brother, Ralph, he was actually planning a career in dentistry, but his traineeship was cut short when his employer and tutor was killed in a road accident. This was a matter of months after the Wall Street Crash, the Great Depression swiftly spreading to Australia, where unemployment reached 30 per cent within two years.

Alick quickly found work in sales promotion for General Motors and briefly as a seaman. In 1932, while in Edithburgh aboard the Warrawee, his father collapsed and died. His body was brought home in the vessel which he had captained for fourteen years. Perhaps it was the loss of his father or his engagement to Muriel that ended his attempt at a maritime career, for soon after, Alick entered the world of newspapers.

His first post was as an advertising salesman for the News, an Adelaide daily owned by the News Limited group, his department managed by Muriel’s brother, Arthur. The News was owned by Sir Keith Murdoch, whose recent knighthood was reward for his campaign against the Labor Prime Minister James Scullin, at the start of the Depression, and for his championing of Joseph Lyons and his newly formed breakaway party, the United Australia Party.

Although never on the editorial side of the industry, newspapers were where Alick excelled. By the end of the 1930s, he was a manager of the News Limited Group in Melbourne. His role expanded into managing Queensland Newspapers in Sydney until, after nearly two decades working for Sir Keith Murdoch, in 1951 he left the News Limited Group to become advertising director of the Melbourne Argus, four years later being appointed its general manager.

Rising production costs and fierce competition had led to the paper being acquired by Britain’s Mirror Group in 1949, and a year into Alick’s time there it became the first newspaper in the world to print colour photographs – a huge feat technologically but one which allowed it to burn brightly for only a short time; the colour printers were expensive and temperamental and occasionally led to the paper not being distributed until late in the morning. In January 1957, the Argus admitted defeat.

However, Alick’s achievements there had impressed the board. They offered him the role of advertising director for the Mirror Group, which he accepted. A few months later, shortly after the death of Muriel’s mother, Frieda,1 the rest of the family arrived in London. ‘My father had gone on ahead of us,’ says Dianne, ‘leaving my mother to sell the house and organise the move, as well as to get teenagers who were very happy in their lives to emigrate, and bless her, she did it all by herself, she was wonderful.’12

Muriel ingeniously devised a gentle strategy for acclimatising the children to the relocation, getting out a map of the world and creating a trip to excite them. The multi-stop flight from Australia alone was a considerable task in those days, but after arriving in San Francisco, she took them on a train down to Chicago, then to Montreal to visit friends, down the Hudson Valley to New York, and finally sailing on the Queen Elizabeth to Southampton, where Alick was waiting for them.

The emotional, geographical and educational upheaval was enormous, Jennifer having to leave Melbourne University without graduating and Dianne and Ian having to leave their schools mid-term, 14-year-old Ian moving from the illustrious Geelong Grammar School, where he boarded, first to lessons with a private tutor in London and then to an equivalent boarding school in England, with Dianne ultimately completing her education in Switzerland.

The following year, Alick joined the Mirror Group’s board of directors, and the McKays moved from their first home in Campden Hill into St Mary House, at that time only a twenty-minute drive from Fleet Street. It is a horrid irony that Arthur Road bore the name not only of Muriel’s beloved grandfather, from whom she inherited her artistic talents, and that of her brother, but of one of the men who destroyed her existence.

The Daily Mirror was in quite remarkable health at this time, reigned over by the megalomaniac Cecil Harmsworth King and his editor, Hugh Cudlipp, the youngest editor on Fleet Street, who helped to make it the biggest selling daily in the world. In 1963, King controlled over 300 publications, including periodicals, consumer and trade magazines, national newspapers and books, and grouped them all together as the International Publishing Company. He appointed Alick McKay as a director.

Alick was by now recognised as one of the most industrious and ebullient executives in Fleet Street. Jennifer McKay speaks adoringly of her father but also with a sense of marvel:

He wasn’t interested in money, although of course they had a nice life. He was just very good at his job. I remember once watching him at a reception, and he worked the room like the Queen Mother. He did not miss a single person and devoted a bit of his time to each of them, something so skilful and yet it seemed effortless.13

He was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire in the 1965 Birthday Honours for his voluntary work chairing the Victoria Promotion Committee, a charity generating tourism and investment in that state. He was by now also a chairman of the Advertising Association, along with several other charitable and corporate bodies. In 1967, sales of the Daily Mirror peaked at over 5 million copies per day. The same year, he suffered a heart attack.

He had in fact already suffered a mild heart attack the previous year. While he had not inherited his father’s devotion to the sea, he had clearly inherited his weak heart, and his health was worsened when, on a boat trip to Australia to recuperate, he fell against a bollard, an injury which developed into another thrombosis. Conscious of his father’s sudden death, after thirty-seven years, having risen from hard-working salesman to decorated and celebrated executive, he made plans for his retirement from the IPC.

By now, the couple were alone at St Mary House and already grandparents to two boys and a girl. After joining the rest of the family in London and working at an advertising agency, Jennifer had moved to Sussex with her husband, Ian Burgess, a property developer and horse breeder. Living nearby were Dianne and her husband, David Dyer, a director of Wilkinson Sword, while Ian was in Melbourne, working in the marketing department of the Hamlyn Publishing Group, which had opened an Australian operation in 1964, shortly after being acquired by the IPC.

‘They were a lovely family, very decent people,’ says former Detective Sergeant Walter Whyte, ‘despite whatever assumptions people might have made at that time about Australian newspaper folk.’ Jennifer told me:

My mother would talk to anyone. In those days, it was not uncommon for people to fly separately, and whenever my mother was on a flight by herself, when you met her at the airport there was always some man carrying her bag for her, who had engaged her in conversation on the plane, and whom she would have kept at arm’s length but yet completely charmed.14

A ‘courageous man’ was how News of the World editor Stafford Somerfield described Alick.15

Margery Nightingale, the McKays’ housekeeper for twelve years and the last person to see Muriel before her abduction, had been widowed in 1964, after which the McKays had suggested that she move in with them, though she chose to stay at her home a mile away. She found Muriel a peaceable person, good at defusing her husband’s occasional crotchetiness. Alick ‘used to say, “I don’t like this” or “I don’t think so and so is right”, but Mrs McKay did not answer him back or get into arguments’.16

A local police constable who would befriend the McKays after their burglary considered Alick ‘a very straightforward man. He would never use four words where one would do. I suppose you could say he was a typical forthright Australian.’17 He found Muriel to be:

… one of the nicest people I have ever met. A very personable woman, very pleasant. There was no side to her at all. Although she was a person who was obviously used to the good things in life, she was completely natural. She was a family woman in every sense of the word, I would say.18

Aubrey Rose, later a defence solicitor in the case, remembered Alick as ‘a very fine man, a decent fellow. That was my impression of the whole family in fact.’19 In an old-fashioned division of labour, while Alick was the breadwinner, Muriel was a great deal more besides being the homemaker. As well as her creative talents, she was on the committee of the local Wives’ Fellowship and involved in charitable work to assist unmarried mothers by helping to establish a local nursery to provide childcare and allow them to work.20

The opinions of those close to Muriel which were gathered in the days immediately following her disappearance are particularly important in correcting some of the misrepresentations of her in previous accounts of the case, particularly claims that she was in fragile health or dependent on medication. Her GP, Dr Tadeus Markowicz, also a family friend, described her as a ‘very young, lively woman, who used to occupy herself with painting and the household’, had ‘a very great enthusiasm for life’, and was ‘very stable and strong minded’.21 Mentally and physically she was a ‘very strong and stable woman’, though one likely to be ‘slightly more affected by shock than the average woman of her age’.22

Her dressmaker, Ellen Richards, considered her ‘a level-headed woman, who was very much involved with her home and family, and I feel that her husband was the foremost thought in her mind, apart from her children, whom she was very close to’.23 In the confusion of her disappearance, Dianne stated firmly that ‘my mother adored her grandchildren. My father and mother were a very happy couple and I have never known any serious arguments between them. Mother was happy and looking forward to going to the Savoy with very close family and friends on New Year’s Eve.’24 In his first statement to the police, the day after her abduction, Alick declared, ‘We have had a very happy life … we have never been parted and my wife loved her home and family.’25

Two misfortunes which had befallen the family would prove to be of great significance to the investigation. The first was in 1963 when, during one of Britain’s fiercest winters of the century, Muriel came downstairs early one morning to find that the family’s two dachshund dogs had died of asphyxiation from a faulty boiler. As a result of this, the McKays were extremely scrupulous about dangers in the home, Muriel always putting a guard in front of the fire when leaving a room for more than a few minutes and sitting up into the night if necessary until a fire had burned out.

The second significant event was that the McKays were victims of a burglary on 30 September 1969. Muriel ‘was most upset and that kept on for days after’,26 although the doctor later insisted that it was ‘no more than any other woman would be in the circumstances’.27

One of a spate of similar break-ins in the neighbourhood at the time, the thieves gained entry via the back door and took £3,000 worth of silver, the television set and the radiogram, though no jewellery. At the trial, Alick said that Muriel ‘always had a feeling that this was something they might come back for’.28 It was kept in the top drawer of a chest in her bedroom, but from then on, whenever the couple were out for the evening, she would carry it with her in a small silk bag. ‘It was not of great value, but it was of value to her.’

Six days after the burglary, Dr Markowicz treated her for suspected influenza and joint pain, but after a further day in bed, she was refreshed by the birthday of one of her grandchildren and drove down to Sussex to see him. It was a measure of the McKays’ love of St Mary House that the burglary did not induce in them any thoughts of moving. Its only lasting and understandable legacy was a mild sense of paranoia. On several occasions Muriel told Mrs Nightingale that she thought the house was being watched, so ‘when we went out, we always looked up and down Arthur Road, but we never saw anything suspicious’.29 Mrs Nightingale was told to keep the chain on the outer door when she was alone in the house, and Alick told Muriel to keep it on in the evenings until he was home. Alick very rarely carried a front door key, so from now on he would use a prearranged ring, of three short rings and a long ring, before she would open the door.

She was also occasionally being pestered by nuisance calls, as were several other local women. One had been receiving numerous calls from two years, which had recently gone from heavy breathing to ‘seductive’ talk.30

Despite having made a good recovery from his heart attack, Alick retired on 2 October 1969. He and Muriel made plans for more regular visits back to their home country, with one planned for the spring of 1970, since they had not seen Ian for nearly two years. But while they were making retirement plans, a revolution was underway in the British press which would have gigantic, irreversible effects on British politics and society, and on the McKay family.

Rupert Murdoch, son of Alick’s first boss in the industry, and the crown prince of a family who had remained close friends of the McKays for decades, had arrived in England and immediately evoked outrage with his purchases of the Sun and the News of the World, the relaunch of the latter spearheaded by the publication of the confessions of Christine Keeler.

The night after Alick’s retirement, Murdoch was invited to defend himself on London Weekend Television’s Frost on Friday programme.2 Pilloried by a match-fit David Frost, he now needed friends that he could rely on. A few days later, he bumped into Alick McKay.

He invited the man whom his father had held in such high regard to join him at the News of the World. The terms were extremely generous and the appointment, as deputy chairman, would in no way interfere with the McKays’ plans for more frequent visits back to Australia, the first of which they had now begun to arrange, Muriel having even made an appointment for the necessary vaccinations for a trip that she would never make.

Muriel’s dressmaker later said that Muriel had been delighted about Alick’s appointment and had told her that ‘Mr Murdoch had no intention of overworking her husband and would allow him as many holidays as he wished’.31 Alick was only required to stand in when Murdoch was out of the country.

It was an offer that Alick McKay could not refuse, and he started in the role on Monday, 4 December. For the McKays, it would have brought prosperity and ultimately delivered them a long and happy retirement, but for a devastating twist of fate which destroyed their happy and industrious lives.

Lady Cudlipp remembered, when Muriel disappeared, being tasked by the police with finding a photograph of her to be used on missing person posters and appeals. They wanted one in which she was not smiling, but Lady Cudlipp simply could not find a single photograph where Muriel was not either smiling or laughing. ‘She was that sort of woman, she was always happy, always smiling.’32 Eventually, a picture was selected which caught her just half-smiling. It is that uncharacteristic image that has remained history’s representation of her for far too long.

_____________________

1 Muriel’s father died in 1964.

2 No recording is known to exist of this edition.

2

PAPER TIGERS

We (the ladies!) are now going to look at the Rembrandt exhibition and walk around the city, which is charming with its canals.

Muriel McKay, Amsterdam, 14 November 1969.

In the half-century since the tragedy, different presentations of this story have selected different central characters and, erroneously, on several occasions that character has been the press. An exaggerated causal connection between the crime and the Murdoch empire persists, most recently presented in James Graham’s play, Ink, in which the Sun and the News of the World conceitedly decide at the outset that this case is really all about them, that it is a crime against them, an attack on their operation, on what they stand for and on what they are doing to Britain (or in their mind, for Britain). In truth, the men who abducted Muriel McKay were not remotely interested in tabloid newspapers and did not even read them.

The reality is that the crime had nothing to do with the tabloid press, though the tabloid press had a great deal to do with the investigation. For, not only were the police dealing with a new kind of crime, they were dealing with a new type of journalism. The role of certain newspapers in the story was obstructive and, ultimately, destructive. They did not inspire the crime, but they did influence its outcome.

It is therefore important to set the stage, to understand how these newspapers operated at the time and how they were perceived, and why the McKay kidnapping sharpened the teeth of every tabloid in Britain, scornful of a story so close to home, to which the newest and most threatening paper on Fleet Street had enviable access. The term ‘tabloid’ is not specific to the red tops, but included, at that time, the Daily Sketch, the Evening Standard, the Daily Mirror, the Daily Mail and the Daily Express. The Sun and the News of the World were not the villains of the piece; although they were granted access which was, with hindsight, a serious if understandable error of judgement by Alick McKay, on this occasion they conducted themselves a good deal better than did their rivals.

The red-top tabloid press as we know it is now in terminal decline. Ongoing costs from the phone-hacking scandal3 and declining sales saw the Sun report a pre-tax loss of £202 million in June 2020.1 The News of the World’s successor, the Sun on Sunday, has an average circulation of 1.16 million copies a week at the time of writing. Unlike the early days of Rupert Murdoch’s ownership of the paper, when it boasted weekly sales of over 6 million, today titillation and disinformation can be found freely and more readily online. Soon it will be possible to forget the enormity of the influence that these publications once had on British society.

Walking down Fleet Street on a Friday afternoon today, a once-exciting street is now a sorrowful place, faintly echoing its past. Like the police force, it once ran on adrenaline and alcohol, and like police officers, some journalists in those days looked for the truth, others for anything that was believable. The once bustling wine bar El Vinos is now a quiet place, and the Wig and Pen pub, where the lawyers rubbed shoulders with the libellers, is boarded up. The only traces of the street’s journalistic past are at No. 186, the fictional home of Sweeney Todd, in reality still the offices of Scottish publishers DC Thomson.4 Slowly flaking away from the walls are painted banners for the long-forgotten People’s Journal, and three publications that still just survive in Scotland: the Dundee Courier, the Sunday Post and the genteel, anachronistic People’s Friend.

Tabloid newspapers in Britain massively pre-date the arrival of the red tops. They were tools forged for an aggressive and enlightened moral crusade by the combative but compassionate W.T. Stead,5 who arrived in London in 1880 after ten years editing the Darlington Northern Echo to become assistant editor of the Pall Mall Gazette, taking full editorial control three years later.

The Pall Mall Gazette was a young and promising evening paper which, forty years later, would be absorbed into the Evening Standard. Tellingly, Stead’s appointment was a piece of puppetry by Gladstone, who recognised that a liberal presence on a gentleman’s newspaper would help to popularise his stony image, which was suffering beside his colourful rival, Disraeli. Stead took up the appointment with zeal.

Eschewing the paper’s original Conservatism, he pioneered a more accessible presentation style, with copy broken up by illustrations and photographs, a look initially known as ‘the new journalism’. By the 1890s, it had been christened ‘the tabloid style’. Superseding the constant columns of punishingly close print, Stead enlivened his pages with crossheads, catchpenny headlines and pictures.

But the phrase ‘tabloid’ quickly came to refer as much to an attitude as to a layout, as Stead’s muscular Christianity, social conscience and quest to expose injustice provoked alarm, outrage and anger. Stead wanted to ‘rouse the nation’ by purifying the heart with ‘pity and horror’, through ‘that personal style, that trick of bright colloquial language … and that determination to arrest, amuse or startle’.2 Although he was helping to mainstream a commercial formula that had existed since the 1840s ‘in half-penny Sunday newspapers, such as the News of the World, Reynolds’ Newspaper and Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper’,3 by foregrounding sex and crime, Stead was presenting these themes to higher social classes, and for higher motives.

Stead’s incredible investigative journalism included an exposure of the horrors of child prostitution, an undercover operation which led to him serving three months’ imprisonment, but also led to the age of consent being raised from 13 to 16. He also conducted a fearless campaign through the Pall Mall Gazette protesting the innocence of Israel Lipski, who had been sentenced to death for murdering his fiancée, the jury having taken just eight minutes to decide a guilty verdict. Stead’s crusade was effective enough to see the execution delayed for a week while a reprieve was considered but, despite Stead’s genuine concerns about scant evidence and possible antisemitic prejudices, Lipski ultimately confessed his crime to a rabbi and was hanged.

Three enduring characteristics of the new journalism are identifiable from these campaigns. The first was the demonstrable impact that the tabloids now had on public opinion and on the government. Secondly, the Lipski case was the creation of what was dubbed ‘trial by journalism’.4 Thirdly, it showed that the tabloid is a merciless beast, never forgiving anyone whom it wrongs, for Stead’s persistent target throughout the Lipski campaign was Police Commissioner Sir Charles Warren, and Lipski’s ultimate confession, vindicating the actions of Warren and his police force, only resulted in Stead from then on attacking Warren at every opportunity. In a hint of the tabloids a century later, Stead’s treatment of Warren proved that the new journalism was as zealous and effective at destroying reputations as it was at creating them.

Five years into Stead’s time at the Pall Mall Gazette, the press and the public were electrified by the Jack the Ripper killings. Stead denounced the ‘vulgar sensationalism’5 of the detailed reports in the Times, but like many other social reformers of the day, most notably George Bernard Shaw, he quickly realised that the crimes had value. To the social reformer, that value was in highlighting poverty, cruelty and neglect in society; to the wily newspaper editor, there was an undeniable commercial value too.

The ability to influence political and legal affairs, trial by journalism, fearless (and sometimes lawless) investigative journalism, aggressive morality and the use of crime as a commodity were now established characteristics of the tabloid press. But whereas Stead’s influences were very much for the good of society, the tabloid press a century later, while using the same currency, had less lofty ambitions. The mentality and the look of them was now developing, but Stead’s prose, although shamelessly emotive, was ornate and lacked immediacy. He described a letter written by a child to the drunken mother who had ‘sold her into nameless infamy’ as ‘plentifully garlanded with kisses’.6 It was not until fifty years later that the language of tabloid journalism was revolutionised.

The Daily Mirror, initially a paper run by and aimed at women, had launched in 1903, and after a slow start had gained momentum, thanks to its pictorial style. However, by the 1930s, it was becoming a casualty of the circulation war, being trounced by the Daily Herald and Daily Express. It reinvented itself spectacularly as a working-class, left-wing paper. Taking its visual lead from American tabloids such as the New York Daily News, its new, direct, colloquial prose style was the voice of its editor, Harry Guy Bartholomew, a sparsely educated and self-made man, who had joined the newspaper as a cartoonist thirty years earlier. The Daily Mirror quickly realised the value of sensationalism, sauciness (the comic strip ‘Jane’) and sympathy with the reader who felt emasculated or disenfranchised.

In 1949, responding to calls for a Press Council, new editor Silvester Bolam defiantly proclaimed in a front-page editorial:

The Mirror is a sensational newspaper. We make no apology for that. We believe in the sensational presentation of news and views … We shall go on being sensational to the best of our ability … Sensationalism means the vivid and dramatic presentation of events so as to give them a forceful impact on the mind of the reader. It means big headlines, vigorous writing, simplification into familiar everyday language, and the wide use of illustration by cartoon and photograph … Every great problem facing us … will only be understood by the ordinary man busy with his daily tasks if he is hit hard and hit often with the facts. Sensational treatment is the answer, whatever the ‘sober’ and ‘superior’ readers of some other journals may prefer.7

Bolam had just completed a three-month jail sentence for contempt of court over the paper’s reporting of the trial of John George Haigh, the ‘acid bath’ murderer.

What is striking about the editorial is how much of it is shared in tone and attitude with the tabloids that were to come, most notably in its suspicion of supposedly ‘superior’ people and its boast of speaking to the ‘ordinary man’, though the Sun of course would go further, claiming to be speaking not just to him, but for him.

While never aspiring to W.T. Stead’s level of benevolence, the Daily Mirror had more of a social conscience than the Sun and the News of the World could ever pretend to possess, but in its reinvention as a popular and populist newspaper in the 1930s with a fiercely unpretentious voice, it gave the modern tabloid its final key ingredient. By now, three-quarters of the adults in Britain read one of the eight daily national newspapers. All that was left was for the permissive age to begin.

Founded with the motto ‘Our motto is the truth, our practice is fearless advocacy of the truth’, the News of the World was the cheapest of newspapers, in price and in taste. A lowbrow, top-selling title of tittle-tattle and giggles, vicars and tarts, that tutted at its own smut, it was scurrilous, salacious and vastly successful from its first edition, on 1 October 1843. By the 1950s, it was selling up to 8 million copies a week.

After 150 years, when it was closed in the wake of the phone-hacking scandal, it was still the biggest-selling Sunday newspaper in the English-speaking world, with weekly sales of 7.4 million. Sir William Emsley Carr, whose family had owned the newspaper since 1891, addressed a hint of a decline in sales in 1960 by appointing as editor Stafford Somerfield, a wily warhorse who had been with the paper since 1945, pursuing ‘salacious Puritanism with missionary zeal’.8

By now, cinema and independent television were creating a gallery of new celebrities, whose antics kept the News of the World merrily lucrative throughout the 1960s. Then, one morning in September 1968, Sir William Carr took Somerfield for a drink in the long bar of the Falstaff, the News of the World