7,50 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Muswell Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

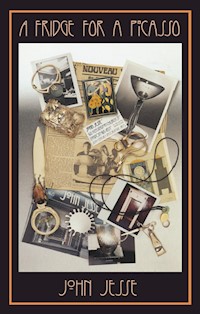

A gallery of famous and eccentric figures animate this entertaining and informative autobiography. Not least is John Jesse who treats life as fun yet established himself as a respected specialist in his field of Art Nouveau and Art Deco. The book is richly illustrated with some of the works he has collected and sold.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

A Fridge For A Picasso

John Jesse

Dedicated to

my children Kells and Tiffany

my wife Jackie

my mother, Betty, who started me off with a piece of painted cardboard

my first client, Godfrey Pilkington

Illustrations

John Jesse. Oil painting by Betty Swanwick, 1947. Collection John Jesse.

Gerard and Lydia. Collection John Jesse

Miss B. Pencil drawing by John Jesse, 1958. Collection John Jesse

The Beach, Ile Ste Marguerite, Cannes, 1958. Gouache by John Jesse. Collection John Jesse

Stromboli. Gouache by John Jesse, 1958. Collection John Jesse

Sally Fleetwood. Ink and watercolour by John Jesse, 1959. Collection John Jesse

Christmas Card. Dye on paper by John Jesse, 1961. Collection John Jesse

The King. Lead. Forgery by Billy and Charley, circa 1860. Collection John Jesse

Melisande. Silver and silver gilt collier, 1900. Collection John Jesse

La Dame aux Camelias. Poster by Alphonse Mucha, 1900. Collection John Jesse

The Sarah Bernhardt Snake Bracelet. Gold and opals. Designed by Alphonse Mucha, executed by Georges Fouquet, 1899

Tourist. Oil on paper by John Jesse. 1964. Collection John Jesse

Tiger Morse. iPad ‘Brushes’ drawing by John Jesse, 2014. Collection John Jesse

Guild of Handicrafts Silver Porringer and Spoon designed by C R Ashbee, 1902. Ex Collection John Jesse

The Parachute Lamp. Bronze and ivory lamp by Richard Lange, circa 1930. Exhibited The World of Art Deco The Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Ex Collection John Jesse

Teapot. Silver plated and ebony handle. Designed by Dr. Christopher Dresser for James Dixon & Sons, circa 1880. Collection John Jesse

Teapot. Silver plated. Designed by Paul Follot, circa 1900. Collection John Jesse

Table Lamp. Etched glass. Daum Frères, circa 1925. Ex Collection John Jesse

John Jesse and some stock. December 1965. Collection John Jesse

Sally Tuffin and John Jesse with Sally Jess and James Wedge in the background at the opening of Paraphernalia. John Jesse wearing one of his Funshirts.

The Voysey Clock by C.F.A. Voysey, circa 1896. ©Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Ex Collection John Jesse.

Sally Jess Handbag. 1967. Perspex and PVC. Collection Sally Tuffin.

Silver and Serpentine Cup. Designed by Archibald Knox for Liberty & Co, 1903. Ex Collection John Jesse

John Jesse wearing hat, 1974. Collection John Jesse

Part of the Plastics section of the Contrasts Exhibition. Adelaide Festival 1976

Invitation card for ‘A Glass Menagerie’, 1982. Collection John Jesse

Art Deco Handbag. Chrome and enamel, circa 1935. Collection John Jesse

Catalogue cover for ‘Useful Animals’, 1987. Collection John Jesse

Objects in Disguise. Photo by Olly Ball, 1983

Will You Marry Me. Ink drawing by Gino D’Achille 1991

The Pursuit of Style. John Jesse at Kensington Church Street, 2006. Sotheby’s catalogue cover

Contents

Would you swap a Picasso etching for a refrigerator?

Probably not.

In the early sixties, Sally and I were looking for a fridge. My boss at the art gallery, with an eye for a good deal, made me an offer. ‘You can have my fridge for £55.00,’ he said. ‘Or, if you like, I’ll exchange it for your Picasso etching,’ which I had recently bought for £40.00.

It seemed like a bargain.

This was my first transaction and paradoxically was probably the catalyst that started me as a dealer. It was also the daftest, as the Picasso continues to rise in value while the fridge is rusting away in a dump.

Part One The Pursuit of Love

Chapter One Barefoot for the Bombs

I wake up inside a chest of drawers. I am four years old.

It is 1940 and the Blitz on London has just begun. An incendiary bomb has hit a gas main near our house in Paultons Square, Chelsea. In the ensuing panic my mother Betty lifts me out of the tallboy and quickly dresses me. We run out into the dark and head towards the corner of the King’s Road where I see a tall and ferocious pillar of flame bursting from a hole in the middle of the street. Surrounding it is a phalanx of fire engines and firemen dousing the flames with great arcs of white water. Already, a large crowd has gathered, their faces flickering and glistening from the spray.

Surprisingly, what I remember more than all the commotion is that my mother had forgotten to put on my shoes. Being barefoot was so strange that it took precedence over the far more exciting flames. Years later, she told me that all I had said that night was, ‘Look at the stars!’

Unlike most children, I was not an evacuee during the war. I was sent to a boarding school in Wimbledon while I was still only four years old.

At night, during the many air raids, the children in my dormitory were crammed into a steel cage known as a Morrison Shelter which the school had installed to protect us, should we get a direct hit from a bomb. I remember once spending a claustrophobic night in it, because the boy alongside me was unable to stop vomiting. None of the teachers heard our cries to be let out. Through a crack in the blackout curtains I could just see the long beams of searchlights sweeping the sky, and flickering flashes followed by the distant thud of guns and bombs. I still remember the words of the patriotic song we sang.

Old Hitler has a bunion.

A face like a pickled onion.

A nose like a squashed tomato

and legs like match sticks.

I didn’t fear or hate the war. I loved it. To me it was part of normal life.

During the school holidays I stayed with my mother in our new flat at Cromwell Place, South Kensington. The artist, Francis Bacon, lived on the ground floor and he sometimes let me into his studio which, to my young eyes, was filled with scary paintings, but the smell of oil paint and turpentine was wonderful. Once, the windows of our flat were blown in by the blast from a bomb, and the heavy purple curtains saved us from being hit by flying glass. As an extra precaution, in case it happened again, my mother taped new panes. There was a blackout in those days and no streetlamps or windows could show lights after dark. Most air raids were at night, and the siren’s mournful warning was the signal for all the tenants in our building to go to the relative safety of the ground floor. Sometimes Francis Bacon would appear holding the hand of his aged white-haired nanny, Miss Lightfoot. Then Mrs. King, the housekeeper, would emerge from the basement with steaming cups of tea for our little group who were chatting and smiling to each other as if they hadn’t a care in the world. But underneath the camaraderie there must have been an undercurrent of fear at the sound of approaching enemy planes, especially when the house shook if a bomb fell nearby. There was almost a party atmosphere, particularly when Bacon plied the grown ups with generous tots of whisky.

The morning after an air raid was an adventure, and when I was older I would run out into the street to search for pieces of shrapnel. These were the jagged and surprisingly heavy fragments of metal from exploded shells. Once, I was lucky enough to find several pieces outside the Natural History Museum. The strange mystical desire to acquire must have already been embedded into my psyche, and the budding dealer in me ensured there was a roaring trade for my souvenirs at school.

Later in 1944, the bombs were more frightening. These were the pilotless German V-1 Flying Bombs commonly known as Doodlebugs. They were launched from across the Channel and on reaching London, ran out of fuel, fell to the ground and exploded. We knew when listening to their approach that the engine could cut out at any time. To this day, if I hear a plane with that unmistakeable sound, it takes me back to that time.

My mother, Betty, was born in Truro, Cornwall in 1915 but her parentage was a mystery. She was put into the care of a foster mother who took her to Florida. She turned out to be cruel and sadistic and beat my mother, often reminding her that, as an illegitimate child, she was born wicked.

Betty was sent back to England when she was fifteen and found a job scrubbing floors in a mental hospital. After many grim adventures and moving from job to job, she gradually made friends and, through one of them in 1935, met my father Toby on a blind date. They fell in love and she moved in with him. His pet name for her was Boodle-Bumpkins.

When she fell pregnant, despite strong opposition from his family because of her lack of pedigree, he decided to do the correct thing and marry her. The wedding took place in a side-chapel at Westminster Cathedral where two witnesses had to be pulled in from the street.

The marriage had fizzled out a few years later when the war began and my parents separated. My father was posted abroad but I never knew where. When I asked him years later he refused to tell me, explaining that he was bound to silence by the Official Secrets Act. Maybe he was doing cloak-and-dagger work. I didn’t see him again until 1947. But for my mother the war years were exciting. She was attractive and single, and with her son at boarding school, she could enjoy her newfound freedom.

In 1942, she was with a group of friends when she met Tambimuttu, a charismatic Sri Lankan poet and prince. He had come to London and launched a small company, Editions Poetry London, which published and illustrated the works of young wartime poets. Out of the blue, he offered her a job as his typographer, which placed her at the heart of London’s literary and artistic world. Her life was changed. She met the artists Graham Sutherland, Lucian Freud, and the sculptor Henry Moore as well as the poet David Gascoyne, and the outrageous Quentin Crisp, with his daring purple tinted hair and painted fingernails. I particularly liked Quentin because whenever he saw me he would put a silver threepenny bit in my hand. Apparently I sat on Dylan Thomas’s knee at a party and at another my mother was the only person to remain seated when everyone stood to pay homage to Oscar Kokoschka. He immediately noticed her rebelliousness and flirted with her, even asking if he could paint her portrait. She turned him down.

The ill-treated and illegitimate Cinderella figure, had arrived at the ball.

In March 1944 she met the young war poet, Keith Douglas, who was negotiating with Tambi to have his poems published. He asked Betty to put in a good word for him and on being given a weekend pass took her out to dinner and was intrigued when, after a small misunderstanding, she flirtatiously called him her bête noire. The words were probably spoken in jest, but they struck a chord and he was inspired to write a poem dedicated to his own Bête Noire. Their meetings, snatched on his infrequent leaves from the army, were incredibly romantic. She was the beautiful muse, while he was the young, handsome and brave poet about to go to war. Over those few months before the D-Day landings, their relationship grew in intensity, and he fell deeply in love with her. In June 1944, three days after landing in France, and a week after he last saw her, he was killed. She gave all of their correspondence to the British Library.

Another man, who was closely involved with Betty at the time, was a medical student and poet, Peter Johnson. They had an on-and-off affair until the end of the war, when he qualified and was posted to Munich to help thousands of refugees who had been displaced. He would turn out to be a major influence in our lives.

In late 1944 my school decided to evacuate to the country because it lay under the path of the V-1 rockets that flew over London. Wimbledon was becoming known as Doodlebug Alley. I was taken away and sent to Beltane, a progressive co-educational establishment in Wiltshire. As usual, I was a boarder.

At the start of the holidays, Betty began a tradition of taking me to the Café Royal in Regent Street for lunch. She often ate there with her publishing or poet friends. Around this time she formed a close friendship with Keith Douglas’s mother. ‘Auntie Jo’ soon became part of the family and often took me to stay with her at her home in Bexhill-on-Sea. On my first trip we joined the celebrations for Victory Japan Day on August 8th at Trafalgar Square. As we stood overlooking the cheering crowds on the steps of the National Gallery, I noticed that the yellowed celluloid face on her watch had a perfect round crack on it. She told me that she wore it because it had belonged to Keith, and that it had been damaged by a direct hit from a bullet. I really coveted that watch. Later, while waiting for the train to Bexhill at Victoria Station, she took me to a News Theatre to watch the cartoons. When the news came on we saw the most horrific images from a concentration camp. The film showed, in graphic detail, weak and emaciated people, either staggering around or just standing with a lost and bewildered look on their faces. And in another shot were piles of naked, skeletal bodies being slowly pushed into long, deep pits by bulldozers. What shocked me most was the image of a woman, warmly wrapped in a thick fur coat, looking down into the carcass-filled pit while pressing a white handkerchief to her face. I was only eight years old and I have never forgotten that film.

Once, after meeting me from school, I was shocked when my mother suddenly began weeping in the taxi on our way to the Café Royal. In between sobs, I discovered that a manipulative Polish refugee named Sophie had tricked my mother’s boyfriend, Peter Johnson, into getting her pregnant. Worse still, he had married Sophie and brought her to England. I felt strangely inadequate as I awkwardly put my arms around my mother whilst at the same time having no idea of what to say. I still remember that she was wearing a dark purple corduroy suit with large round gold ceramic buttons.

But she was in a light hearted mood when, in late 1946, she took me to see Britain Can Make It, an innovative design exhibition at The Victoria and Albert Museum put on to boost post-war British trade. The museum’s regular exhibits were still stored for safety in the country and the vast empty interior had been taken over for the show. After the usual long queue we shuffled along roped barriers, following the arrows, passing the mocked-up furnished rooms, complete with radios, vases and lamp stands, until we got to the clothes section. This was the part of the exhibition that fascinated my fashion-hungry mother, and she fell in love with a colourful silk Jacqmar scarf, only to be told that although everything was for sale, the British themselves were excluded from buying. The objects on show were for export only. This was why some people were calling the exhibition Britain Can’t Have It!

After a few months, Betty had a new boyfriend, the poet Ruthven Todd. She was offered a new job in Paris, broadcasting to England for Radiodiffusion Française, and for my Christmas holidays we flew to Paris with Ruthven. She had rented a bed-sitting room on the Left Bank, and I was put upstairs in an attic where the Symbolist poet, Paul Verlaine, had once lived. It had a beautiful view over the rooftops and I could just see the Eiffel Tower.

Ruthven was a wonderful friend to me because he was generous with presents. My favourite was a gift of the recently invented Biro ballpoint pen which was still scarce. I knew it would impress everyone at school. My mother quietly told me that she thought that most of the presents he gave were shop lifted. There were shortages in Paris as well as at home, so we were pleased when he came round on Christmas morning with a scrawny chicken he had bought (or nicked) for our dinner. As there was no oven it had to be boiled, which turned out to be quite a problem, as the only way to create heat was to set light to a tin of jellied methylated spirits which gave out a pervasive smell and a blue flame. It took all day to cook.

On the way back to England he gave my mother an exotic and beautifully packaged perfume by Schiaparelli called Shocking. I didn’t know that twenty-five years later I would be looking for the empty bottles of that brand to sell in my shop.

Chapter Two The Runaways

My first girl friend was at Beltane School, a nine year old lonely and unpopular girl called Sylvia, with straight shoulder-length mousy hair and a strong Somerset accent. There were rumours that she was a school-thief, but I couldn’t believe this and felt protective towards her. Throughout the summer terms, instead of going to lessons, we spent most days playing together under an old yew tree. We would act out fantasies by playing the parts of doctors, nurses or princes and princesses, ad-libbing through fairy tales, love stories or tragedies. Sometimes she directed, but mostly it was I who was the star, director and producer.

During the autumn term when Sylvia and I were playing in one of the transparent Perspex glider noses that Mr Tomlinson, the headmaster had installed, we somehow found out that when you sucked very hard on the underside of the arm a large red welt appeared. This was a thrilling discovery and, after a lot of sucking and giggling, there was soon no room left on our arms. We then experimented with other parts of our bodies, the most successful being on each other’s necks. Without warning, Ruth, the house matron, who had seen what was going on, burst in. ‘You nasty dirty children!’ she screamed. ‘What do you think you are doing? I forbid you to play with each other again!’ Both Sylvia and I were terribly shocked and upset, because we had no idea that we had been doing anything wrong. We couldn’t understand why, for apparently no reason, we were being punished. With her words echoing in my head, I decided that the only thing to do was to run away from this mean and unfair school. I now had my own bike and had no trouble ‘borrowing’ one for Sylvia. Then, bursting with indignation, I scribbled a letter to my mother telling her of my intentions and sneaked out of the grounds to post it. What excited me most in my childish and imaginative storybook world was the thrill that we would probably be hunted down by the police and have to swim across rivers to hide our scent from the following hounds. Many years later my mother gave me that letter.

Dear Mummy

I am not being silly. I am so unhappy at this school that I can’t stay here. Sylvia is not being silly we are both going away keep it a secret for my sake. But I hate it here so much that I curse it all happened to-day that we decided to go because of Ruth. We were playing on Sylvia’s bed and then going to tidy the bed when Ruth our Matron for no reason at all came and said that we should never play together again or go into each others bedrooms and I don’t call it fair. I will Kill myself if you tell tommy or get the police after us

John Jesse xxxxxx your warning

Finally, I secretly sent a message to Sylvia via a friend to meet in the bike shed, and we boldly cycled out of the school gate at lunchtime. Once we were actually in the process of running away, it was not as much fun as we had imagined. Cycling was tedious, particularly as we didn’t know where we were going or where we would sleep. The worst thing was that, as soon as we were on our way, it started to pour with rain. With no coats on, snacks or bottles of water, we cycled through the Wiltshire countryside for about fifteen miles, constantly looking over our shoulders. Of course it was a bit disappointing that there was no sign of police cars, or even the baying of hounds in hot pursuit. As we doggedly rode on, the enthusiasm at the start of the journey began to change from determination to misery and dejection. By the late afternoon we were wet, tired and thirsty as we struggled up a long, steep hill just outside Chippenham. Eventually we had to dismount and grimly push the bikes up the last few hundred yards. At the top was a row of little houses with neat front gardens. I knocked on the door of one and asked for a glass of water.

The old lady who answered the door kindly invited us into her home and sat us down on her comfortable chintz-covered sofa in the front parlour. She gave us long cool glasses of lemon squash and some biscuits, and as we slowly thawed out, so she gradually won our confidence. She was very curious as to what we were doing and it didn’t take long before I finally blurted out our saga in the mad hope that she would understand and help us on our way. But this was not one of our made-up stories being acted out under a tree. This was real life. Immediately concerned, she asked which school we had run away from and although she was genuinely impressed by the distance we had travelled, she said that we must go back. I think that Sylvia and I were relieved when she picked up the phone and dialled the local police. ‘I have two ten year old children with me who have run away from Beltane School. Please could you notify the headmaster.’ Looking back, I find it remarkable that, suddenly confronted by these two bedraggled kids, wet through, their necks and arms covered with livid love bites, she stayed so calm and understanding,

A police car arrived, and after stowing our bikes in the boot we were taken to Chippenham Police Station and put in a cell to wait for Tommy. The police were kind and humorously joked about disobedient children ending up in prison forever and ever. I remember that the cell consisted of a single wooden slatted bed, one end of which lifted up to reveal a tin lavatory. On the walls were scratched messages of despair from previous occupants. After a couple of hours Tommy arrived to take us back. We hadn’t even been missed. During the drive he was very sympathetic as he listened to our reason for absconding and assured us that we had indeed done nothing wrong and that there must have been a misunderstanding. Apparently, no child had ever run away before, so he asked us to keep this adventure to ourselves. We were relieved and surprised that we were not going to be punished or expelled. Finally, when we arrived back at the school, he said wryly, ‘Isn’t it extraordinary that the one cottage you stopped at belonged to the Chief Education Officer for the County of Wiltshire.’

I never saw Ruth again, so imagine that she must have been fired. The ‘borrowed’ bike was returned, and the following day my worried mother arrived. After talking with Tommy she was amused by the whole affair. I have often wondered what she must have thought when she opened that suicidal letter. I was a lot older before I understood what all the fuss had been about.

In the summer of 1947 my father came to London. He had been living in Istanbul since the end of the war. My mother told me that he had a Russian girlfriend so, when he arrived, I wasn’t exactly friendly. He felt like a total stranger who was not prepared to butter me up by giving me presents like my mother’s boyfriends did. He treated me like a small child. By contrast, Betty let me wander around London on my own by bus or bike. Mostly, I remember being bored as he dragged me around Soho trying to sell the fishing tackle and flies that had been bequeathed to him by his father. Unknown to me, the main reason for this visit was to finalise their divorce.

When it was time for my father to return to Istanbul, I was really glad to see him go and waved goodbye with relief. But on that same day my mother took me to Chessington Zoo and, strange as it may seem, the only wish I made at the Wishing Well was to go to Turkey.

By 1948 my parents were granted a decree nisi and I remember being reassured by both of them that they would always be good friends. They remained firm enemies for the rest of their lives.

Ruthven was out and Peter Johnson had been forgiven and was back on the scene, but he and Betty were having rows. This was because Sophie, who was now divorced from him, was demanding huge amounts of alimony. She was an arch manipulator. My mother constantly complained about her hold over him, particularly when he acquiesced over her demands for more money. A few years later Nicky Johnson, their son, was enrolled into the French Lycée, and just the thought of the school fees that Peter would have to pay became a sore point. Nicky grew up to become a principal dancer with the Royal Ballet.

Nevertheless, to mollify Betty, Peter found a small weekend cottage at a peppercorn rent in Romney Marsh. It was isolated and primitive with no electricity or hot water. There was an outside lavatory and the garden was covered with pyramid shaped concrete tank traps, placed there during the war. Romney Marsh was exposed and windy, with tall rushes swaying and whispering in the dykes. Every morning I would walk down the lane to collect milk or eggs from Mrs. Milton, the farmer’s wife, and her red faced husband who often let me help on the farm.

I must have been quite an irritating boy because I lived in my own world and had little sense of time. Once, I had gone out with the farmer’s son to hunt for birds’ eggs and we wandered far away, completely engrossed in our task. When I came home carrying my delicate prizes, it was already dusk and long after suppertime. My mother, who must have been frantic with worry, completely lost her temper with me for being so late. She snatched my little box of eggs and threw them into the garden. Then she set about me with a washing up mop and sent me upstairs to my room without anything to eat. As I cried, I heard that she too was weeping. The next day, filled with remorse and regret, she gave me a big hug and we made up. I think this memory of her is more vivid than any other for the simple reason that, because she was not very demonstrative, that hug was worth all the pain of the evening before. For once, this was a real physical and warm connection between us. Many years later, I had another row with her, but with a very different ending. At the height of the argument, I tried to outmanoeuvre her and confidently stated, ‘Well, at least I know you love me.’ And, quick as a rapier’s thrust, she replied, ‘Do you?’ After that, I was never sure of her love.

John Jesse· Oil painting by Betty Swanwick · 1947

Chapter Three The Turkish Bath

I was eleven when my father arranged for me to spend the summer holidays in Istanbul with him and his new wife, Katya. All through the previous year I had fervently wished for nothing else, and was very excited when Betty finally took me to the bus terminal near Victoria Station. A label with my name on was pinned to my collar and I was put on the coach for Northolt Airport. I remember looking down at my mother talking to the stewardess assigned to look after me. Then she chatted to a man who was sitting behind me, and I heard him tell her that he too was going to Istanbul. ‘Please keep an eye on my son,’ she called out, just before we left. ‘He is travelling on his own.’

In those days, when planes had propellers, the journey took thirty-six hours. We took off at midnight and arrived at the first stop, Nice, just in time for breakfast in the airport lounge. When we re-boarded, my mother’s new friend from the bus now sat next to me. He was Turkish and he took his duty of looking out for me seriously. He taught me a few useful words in Turkish and was so good at making me feel grown up that I really enjoyed his company. He was about thirty years old, and told me he was a businessman. The next stop was Rome, where we arrived in the afternoon. After disembarking, the passengers were taken to the centre of the city to stay overnight at the Hotel Reale. When we were in reception I was allotted a room with the Turk. In the early evening he took me in a taxi to see the sights of Rome and I felt important and on top of the world. It was so pleasant to be listened to and to be treated as an equal. At dinner, in the marble colonnaded dining room, I was even offered wine, which made me giggle as I found it almost impossible to swallow. Once back in our room, he calmly said that it was bedtime now and began to undress me as he had decided that I should have a bath. Completely trusting and with no suspicions at all, I climbed into the steaming bath and wasn’t even worried when he got in himself and sat behind me. He began by washing my back. Then suddenly, everything changed as he soaped me and pulled me close against him and the pain of what he did was excruciating. I yelled out and began struggling and splashing to get away from him, but his strong grip tightened as he held me closer. Somehow I squirmed myself away, slithered out of his grip and scrambled out of the bath. I was shivering with fear. I can still recall how apologetic he was and how he begged for forgiveness. I hated him with such venom that I could not even look in his direction. He tried everything he could to calm me, but I stayed as far away from him as the room allowed. It never occurred to me to run for help, as I had the feeling that somehow I was to blame and that the whole episode was my fault. I developed the idea that he was going to steal from me and placed my little brown leather suitcase with my initials on it under my pillow, and painfully sat on my single bed with the blankets wrapped tightly around me. I spent the entire night trying to read Gulliver’s Travels while he slept. Every now and then he would wake up and tell me to lie down and go to sleep, but I was far too afraid that he might hurt me again. I couldn’t drop my guard for an instant and stayed awake all through that long night. Looking back, this was the single most terrible event that happened to me and it has affected me ever since. It was a wound that has never healed.

The next morning I went down to breakfast very early and chose to sit at a table that was so full of other passengers that my enemy couldn’t join us. The stewardess assigned to look after me had stayed in Nice, so I was on my own. But there were two young and friendly RAF pilots travelling to take part in an air show in Istanbul, and I attached myself to them. I didn’t look in the direction of the Turk for the rest of the journey, nor did I dare to tell anyone. Finally, we landed in Turkey late that evening. While saying goodbye to the young pilots at the airport, I introduced them to my father who was there to meet me, and he invited them to a cocktail party he was giving. In my childish way, I begged them to come, even going so far as to make them promise. I had turned them into my saviours, although they knew nothing of what had transpired in Rome. A few days later my father told me that they had both been killed when their plane crashed at the air show. It was a terrible blow, and I was inconsolable with grief.

My new Russian stepmother, Katya, was quite pretty, her face with its arched eyebrows glowed as she didn’t wear much make up, and she scraped her hair tightly back from the temples, pinning it into a kind of muddle at the back. She and my father lived, with her old, skeletal mother in the centre of Istanbul, and from his flat he ran his business, the Near and Far East News Agency. On most days he lunched at his club in Taksim Square in order to catch up with the news from fellow newspapermen. In the evenings, he socialised at endless rounds of diplomatic cocktail parties given by all the embassies and consulates.

Katya was born in Soviet Russia and went to the same state school in Moscow as Stalin’s daughter. She told me that her family had lost all their land in the revolution. It was now a collective farm. Before the war she had moved to Warsaw with her mother, and worked as a secretary at the American Embassy. In September 1939, when war was declared, Poland was invaded by Germany and Warsaw was surrounded. She often talked of the wasteful extravagance at the US Embassy because, even during these difficult times, the chandeliers were lit with candles while the besieged population were living without heating or light. When at last leaflets were dropped, offering safe passage out of Warsaw to all the diplomats and their staff, to Katya’s surprise and dismay there was no room for her. She was given the feeble excuse that there was too much diplomatic baggage. Left behind to endure food shortages and the horrors of the Siege of Warsaw, she told me of having to step over dead bodies when she went out to find black market food and water. She felt it was a miracle that she and her mother survived. Once the Nazis had marched in and occupied Warsaw, she took a gamble to trick the German authorities by inventing a story that she urgently had to join her American fiancé. She had typed fake love letters and a proposal of marriage from an imaginary diplomat on official US Embassy headed notepaper. By using all her feminine wiles and perfect knowledge of the English language, she and her mother succeeded in bluffing their way out of Warsaw. They were finally given the precious visa and boarded a train to Istanbul. Once there, with her excellent qualifications, she found a job at the British Embassy and that is where my father first met her. He had presented her with a bouquet of flowers in order to get a quick appointment with the ambassador and their relationship followed.

My twelfth birthday party was held in the house of the as yet un-exposed spy Kim Philby who was at that time First Secretary at the British Embassy. He took us for a trip on the Bosphorus in his smart speedboat, The Blue Jacket, and at some point I fell overboard and had to be fished out.

My father tried very hard to connect with me, but I found that his awkwardness made it difficult to warm to him. One of the reasons was that he would tell me one moment that he wanted to be my friend, and in the next, send me to my room for some minor naughtiness. I never knew where I was. I was once punished to a whole day of solitude, because I owned up to swapping a letter writing set that he had sent to me as a birthday present, for a miniature bird-shaped penknife which I had then presented to Betty. It seemed completely unjust to me that such a small thing could cause him so much fury. I had hated the present with its implied message of ‘write to me’ and felt it was perfectly natural to exchange it for something I liked. Giving it to my mother caused his anger. I was beginning to learn that whenever I mentioned her name, his mood would darken. All those promises of everlasting friendship with each other the summer before meant nothing.

When I returned home, I was surprised to find that Betty had sublet our flat in Cromwell Place so that she could set up home with Peter. Even worse was discovering that my collections of comics, bus tickets and other loved treasures had been thrown out in the move. It was unforgivable.

My home life was becoming unsettled and the first intimation of change was when Betty told me that she was pregnant. She was living with Peter in Bramerton Street, Chelsea, where he had set up his consulting rooms, as he was by this time not only a qualified medical doctor, but a psychiatrist as well. Then she warned me that there was a real possibility that my father would be coming back to live in London as the News Agency was closing down the following year, and when he was settled I would be living with him in Cromwell Place. The divorce had given him full custody and control.

Joanna was born at the end of June 1949 and the price of a new sister was that the tradition of the smart lunch at the Café Royal at the end of term was scrapped. The next shock was when I was told, just before returning to Beltane, that my father couldn’t afford to pay the fees any more, so I was leaving. There was no warning at all. I had loved the freedom at that school and now there was no chance to say goodbye to my friends and, in particular, to Sylvia.

A place had already been found for me in a less expensive progressive school in Hampstead called Burgess Hill and I was to be a weekly boarder. For the first time in the course of my education I was going to know what it was like to stay at home during term time, even if only for weekends.

Burgess Hill was run on similar lines to Beltane. Attending classes was encouraged but not compulsory and we addressed our teachers by their Christian names. My favourite by far was the author Peter Vansittart who taught English language and English Literature. He was tall, wiry and often dishevelled, wearing the same old tweed jacket and wrung-out shirt, half tucked into his trousers. Most noticeable however, though never mentioned, was his uncombed toupée, which gave his gaunt face the look of a ram. I imagined that it hid the scar of a wound from the war. He was about thirty years old and his eccentricity and untidiness set him apart from the other teachers. If I ever had a ‘pash’, as it was called, it was for Peter Vansittart. I really wanted to impress him. He was, without doubt, the first person to instil a joy of learning in me. His voice, when reading aloud the works of Ezra Pound or Dylan Thomas, was mesmerising. He inspired me to read more adventurously, singling out books such as A Voice through the Clouds by Denton Welch or novels by Dostoyevsky. ‘Always reach further into the depths of your imagination and experiment,’ he advised. It was because of him that I started work on a project to dramatise the life of Queen Boudicca with a cast of thousands. Always the dreamer, I saw myself as a budding playwright heading for fame and Hollywood. I discovered that subjects that had previously bored me like history, geography, art and even biology had suddenly become interesting. But paradoxically, when I took my GCE exams in English, I failed. It seemed that Peter Vansittart had given me inspiration but not the art of punctuation. The French teacher, Ruth, was a demure self-effacing blond with an Eva Peron hairstyle. The only thing I remember about her was the surprising advice she gave to calm my nerves when I was about to take the French Oral exam. ‘When you go in,’ she said, ‘imagine that the examiner is in her underwear.’

Peter Johnson was becoming well known among his peers as a brilliant diagnostician. Often at lunch he would tell stories of some of the strange habits of his patients. Their names were never mentioned but I found their obsessions and phobias fascinating. There was a girl of seventeen who wouldn’t eat and was so thin that she had to be admitted to hospital. Peter found her case interesting and difficult because, for all the talking and reasoning with the girl and her family, she still refused food and was slowly starving to death. But one day, after remembering that when she smiled she often unconsciously covered her face with her hand, he had an idea and gently suggested that if she were agreeable he could organise for her to have an operation on her nose to make it prettier and smaller. He found a surgeon to carry out the work and within weeks after the bandages were removed she began to accept her new face. Her appetite slowly returned. By good judgement and luck he had diagnosed that the core of her problem, put simplistically, was her lack of self worth. It was an unusual way to treat Anorexia Nervosa and maybe still is. When Peter was out, I would steal into his consulting room and leaf through his medical books. It was irresistible reading but carried a price. I would soon imagine that I too was suffering from the bizarre symptoms described.

Around this time Peter asked me if he could marry my mother. I was very surprised and flattered as I had presumed, since the birth of Joanna, that they were already husband and wife. Many of my mother’s boyfriends had tried to buy my friendship with bribes, but with Peter it was different; he listened to me and since he had appeared in my life during the war I had grown fond of him as a surrogate father. His request made me feel important and I gravely gave my permission. However, when he did propose, my mother declined. Most of their rows were about the demands of Sophie for herself and Nicky and even though Peter was trying to juggle the two households at the same time, my mother wasn’t sure enough of him to commit herself.

When they came back from a short holiday in France they both succumbed to a nasty, flu-like illness that Joanna and I also caught. The entire household was laid low. After a week we all got better, apart from Peter who began to complain of a strange tingling in his arms and legs, rather like pins and needles. When he started to have difficulties breathing, the doctor was called again and Peter was rushed to hospital as an emergency, where he was quarantined and immediately put into an iron lung. He had poliomyelitis and nearly died. I have often wondered whether the rest of us, though very ill, had caught a milder form of polio, which fortunately didn’t give us paralysis.

While Peter was recovering, my mother decided to marry him. She told me many years later that she did it out of pity but as that was after their acrimonious divorce ten years later I’m not inclined to believe her. Now that they had their new baby, looking after me was an added burden to their already heavy workload. My father had returned home and I was going to live with him. It was a prospect that I dreaded.