Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Set in a sunlit clearing between two World Wars, this personal narrative describes the author's earliest memories of life at home and on the farm in the Pennines, of family, relatives and friends, school and chapel, and the excitement of travelling fairs and Christmas dos.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 231

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

A PENNINECHILDHOOD

ERNEST DEWHURST

For Renée and our family for their encouragement and support

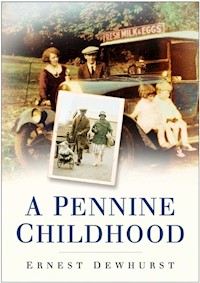

Title page photograph: Grandma Hargreaves and her five daughters.

First published in 2005

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2012

All rights reserved

© Ernest Dewhurst, 2005, 2012

The right of Ernest Dewhurst to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 8022 0

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 8021 3

original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Acknowledgements

Overture & Beginners

1. Lamp Lighting at Tum Hill

2. Parents

3. Stablemates

4. Callers

5. The Shining Hour

6. Boy

7. Rosycheeks

8. Thespian Hens

9. Black, Blacker, Blackest

10. The Milky Way

11. Bread & Water Magic

12. The Phantom Painter

13. The Unquiet Tuesday

14. A Schooling

15. A Team Selector’s Nightmare

16. Hay & Hop Bitters

17. A Windfall of Uncles & Aunties

18. Grandmas Mainly

19. Grandma’s ‘Do’ & the Winter Scene

20. Bread of Heaven

21. Ghosts on Cardboard

22. Countdown

23. The Jesse James Affair

24. Spy Catchers

25. A Funny Thing Happened . . .

26. An Affair with Marge

27. Girl in the Blackout

28. Townie

29 On the Pink

30. Another Upper Room

31. A Past Revisited

Acknowledgements

I’m indebted to Roy Prenton, editor, and Peter Dewhurst, news editor, of the Nelson Leader and Colne Times for use of background material on events and on the period from their files and for several archive photographs and to Peter, my son, who took current photographs of the settings; also to the staff of Nelson Library for access to their newspaper files and to the Independent Methodist Resource Centre for use of its archives.

I’ve included, with appreciation, several facts from W. Bennett’s The History of Marsden and Nelson and drawn on the farm aspect from an article I wrote for the Guardian newspaper forty years ago. I’m grateful to the Inklings Writers’ Group in Liverpool for patient listening and advice, to Jim Bennett for his assessment, to my wife Renée, Geoff and Sandy, Peter and Diane and to Peter Milner who have given encouragement. I value, finally, the example of my great-grandfather, grandparents and parents who laid the foundations for my life and this memoir.

Mother (second right) and friends.

Overture and Beginners

What past can be yours, O journeying boy

Towards a world unknown.

Thomas Hardy

Alocomotive, fuelled and watered, stood wheezing and impatient in Bolton railway station. It was the 1850s and the oil-glimmer place was little more than a shed and booking office. The engine, of the Stephensons’ period, with open cab and tall chimney, would have carriages varying from padded to painful according to the pockets of patrons and some possibly open to Lancashire rain, with holes in the carriage base to let water out. Class distinction had transferred pompously from road coach to rail and perhaps Sir Osbert Sitwell was justified in his claim that trains summed up ‘all the fogs and muddled misery of the nineteenth century’.

Carriage doors closed with assured thuds. Less assured was the boy, third class, confused, alone, unwanted. In his pocket was a single ticket, a one-way to Colne on the boundary of Lancashire with Yorkshire. Pinned to his jacket was a scribbled label confirming rejection by his stepfather: ‘ANYONE CAN HAVE THIS LAD THAT WANTS HIM’.

The guard’s whistle pierced the gloom of boy, station and times. The engine coughed and smoked and shuffled its passengers out of a station which some years before had seen the baptism of the Lancashire Witch, a locomotive built by Robert Stephenson. The boy, committed to the unknown with less certainty than a goods parcel, was steaming towards Colne, overlooked by the Lancashire Witch country.

The boy was my great-grandfather and the one-way steaming and the train of events to follow were to colour the outlook of my family and faith into, and through, the twentieth century. The harshness of his Victorian childhood was in harrowing contrast to my own –on a Pennine farm below the empty moors that whispered out towards the Brontë parsonage and the birthplace of Ted Hughes, a future laureate, and above cotton mills, milk rounds and markets, chapels and chip shops, gaslight and gossip, cowboys, comics and classrooms – and all in a dappled clearing between two world wars. The evocation begins in the 1930s and drifts through the Second Darkness. . . .

Ernest Dewhurst, 2005

1

Lamp Lighting at Tum Hill

I stood tip-toe upon a little hill . . .

John Keats

Dad farmed on a slope. If I’d lived at Tum Hill for a lifetime I might have developed a slant. The farmyard sloped, the middle field had its tilt and the top pasture bucked and dipped like an unbroken colt as if to indulge its elevated status. It resembled an assault course and may have been one, for it was once part of an Iron Age hill-fort. With its hint of the empty Brontë moors beyond, it could never expect the mowing machine. If mowing had been attempted horse, machine and man could have rolled down towards the house. The bottom meadow was odd. It was flat.

The slopes were no threat to a growing boy founded on milk and eggs. The darkness was. I had never known such darkness. It fell each evening as if some monster had blown out the sun and thrown over us a heavy tablecloth like the one under which we played tents but a million times bigger and with no escape flap. Inside it haunting shapes and figures loomed up like the ghosts on Dad’s box camera negatives. The black one watched us through windows and leaned against the door, waiting for Dad to light his storm lamp, go outside and be gobbled up by it. He always came back. The bedside prayers saw to that. Even when stars pinned back the night sky shadowy arms clawed out at me. The glow of oil lamps and coal fire inside the farmhouse could not shut it out entirely, and upstairs, first to bed, I had to have a small lamp and the stairs door left open on the thin gauze of fireside conversation. My fears would linger long, and even in bolder years Dad would post a storm lamp at the top of the short brow to the farm, a lighthouse to wink me home from winter school or Sunday School events.

Winds would howl like wolves up the farmyard, snatching at doors, scattering dogs, cats and buckets and licking up the rainbows of oil leaked into puddles from the milk van. Sheltered in the first years of life in the valley below town I had never been aware of such gales and expected them to send barn roof, hens and dad bowling off into Yorkshire. But snow was a silent intruder. It came by night, quieter than a whisper, and besieged us inside soft barriers. Looking back, neither blizzards nor gales were too common and were relieved by the armistice of a benign spring giving impartial warmth to cowslip and cowpat. Darkness was different. It called every night, but then everything was black or white to a boy.

The farm was a dozen miles across the Pennines from where the Brontë sisters had imagined their way into world literature over a smoky peat fire. Their moor was in Yorkshire, ours in Lancashire. Somewhere among the becks and cloughs and waterfalls on the weathered fells a change of vowels marked the boundary almost as vividly as stone wall or stream. Our hill was not nearly so bleak or solitary as their wuthering heights but to a boy shorter than the lower half of a stable door the farm seemed prey to every tantrum of weather even on ours, the lowest rung of the climb. Charlotte, Emily or Anne were not mentioned much in our home. Dad was more absorbed with his lamp-lit keeping of milk and egg records and simply buckling to than the novels of three quaint sisters in a consumptive parsonage, though the subsequent death of one of our relatives from tuberculosis was an echo of their damp times.

Dad had been apprenticed to iron-turning and was a convert to farming. The farm scene had been more in Mother’s blood as granddaughter of a farmer and the oldest of six children of a farm auctioneer and valuer who died at forty. Mother and Dad clicked to courtship on their way to different chapels and when I was born lived in Blacko, a hillside village little more than a shepherd’s whistle from Yorkshire but enough to give my accent its red rose tinge. The cottage was on an old turnpike where tolls had been charged at a toll house opposite the George and Dragon Inn at Barrowford. At one time a horse passed through for 1d, a horse with chaise for 6d and twenty cows for 10d with a fee for dragons overlooked.

The milkman cometh Dad’s first milk van. Matey (Ernest) and Marian are on the running board, and Mother and Dad are behind.

The Barrowford toll booth today.

In the year that I emerged, 1926, the world lost Rudolph Valentino and gained Princess Elizabeth. My entry, ginger and whining with a hint of freckles and fidgeting to come, may not have been as conspicuous but I was not held responsible for the General Strike. We moved to Linedred, between river and Leeds and Liverpool canal. From there Dad jingled milk by horse-drawn float with ornate lamps into the Victorian new cotton town of Nelson which owed its name to the old Nelson Inn and, in turn, to the admiral himself. A jalopy with running boards and rooftop sales slogan followed but by the time of Tum Hill Dad had moved up to a small blue van with his name in gold letters on its door. ‘What yer gooing up thear for? It’ll be that cold i’ winter.’ We went and wrapped up. The flitting van, probably the ubiquitous Wesley Clegg’s, climbed through town with our belongings in the early 1930s and squeezed along a lane and through the yard of Gib Hill Farm which had more land than us, a milking herd and Irishmen for making its hay. Ours was Little Gib Hill, the farm at the end of the lane, and marked out by that small prefix as junior neighbour. On medieval maps the name may have meant Tom Cat Hill. Whether the removal men saw any tomcats was never made clear but perhaps the grumbling of their gears on that last tight brow by a colour-washed old cottage put them to flight. If Dad had known all the chains and sacks and ashes needed on it in ice or snow he might have himself turned tail and fled with his flitting downhill again. I was glad he didn’t.

The farmhouse today, restored as a private residence. Pendle Hill is in the distance.

Gib Hill was one word on old maps and may have referred to the bigger holding of our neighbours, Mr and Mrs Walter Bather and their two daughters; in the seventeenth century a Mr Ridiough kept six cows and fifteen hens on 9 acres there. Dad’s land stretched further than a boy could see, even on tiptoe, though some may have dismissed his 14 acres as ‘nobbut a pocket ‘andkerchief of a place’. But there for a year or two he was to persevere with hens, a few stirks, a snuffling of pigs and the delivery of another farmer’s milk into Nelson with over 30,000 people. The town smoked away between us and Pendle Hill, where a beacon had blazed out the defeat of the Armada and George Fox had a vision before founding the Quakers. We looked across the valley of Pendle Water, a river, to Pendle, which fell short of mountain status by 170ft. If capped, some said, we could expect rain. It seemed fond of its cap. The Tum Hill area was also known as Castercliffe. Our farm, the lesser Gib Hill, was a humble living but it had a soul.

We were a household of four, two parents, an unmarried aunt, Martha, biblical by name and practice, and the one ginger fidget. For one period there was extra help on the milk round and for specials like haytime aunts and uncles would bolster the labour force. The farmhouse had its back to a middle meadow and was tethered to a barn, shippon and stable in line abreast. The small house had a living room warmed by black oven and boiler range, kitchen with stone slopstone and water pump, cool store and bedrooms. Three stone flags from the front and only door gave on to an earth yard and a flagged path hugged the buildings to the bottom gate. The coal shed was handy but the lavatory anything but a convenience. Lavatory was a euphemism for a board with a hole over a short drop and a draughty door with scraps of the Nelson Leader on a nail. It was somewhere down the yard, and paying calls could be a gamble on a foggy foggy night – especially if the newspaper had run out – and it was some relief that chamber-pots were still in fashion.

As with any house removal, and more so to a farm, there was the novelty of settling in with fresh sights, sounds and smells. There was little garden but Mother, who wasted nothing, needed no more than eyes, fingers and scissors to exploit nature – young nettles for nettle beer in spring, wild flowers to deck the home in summer, holly over picture frames for Christmas. In autumn her purpled fingertips and scratched forearms forecast blackberry pie, and if on her searches she chanced on the eggs of a truant hen in grass so much the better. The farmhouse took on a homely smell of its own, our smell, mingling the outdoors, with woodsmoke and paraffin, with whatever was the domestic ritual of the day, Rinso and bubble and squeak on Mondays, baking on Thursdays, furniture polish on Fridays, a timetable rarely altered.

There were times when the nose could have used a peg, like when Mother’s hand was inside the reverse end of a chicken, ‘cleaning it’ on the big square table with its heavy tablecloth (mainly for weekends and the eyes of visitors) temporarily removed. I would be engaged in Custer’s Last Stand or some Great War attack on my side of the table but there would be no retreat for the general-in-command or later Meccano constructor from that stink of surgery, and the toy farmyard was more in keeping with such table sharing. Outdoor smells could outflank sound or sight and the nose had to be educated into new encounters, from hen pellets and creosote to the patron saint of pong, the Muck Midden, with its dining club no one would wish to hear about. The provender shed smelled almost appetising and grass had seasonal treats for the nose, first when newly cut and then when rafter high in the barn, giving off a fusty, cuddly warmth of which cats, dogs and less domesticated squatters took advantage.

One of Mother’s customs was to make a soft cheese and suspend it in a little cloth bag from the slopstone tap, drifting out an acceptable aroma. Baths had to be taken in a tin bath off its peg on a wall and as I bathed, with little enthusiasm, in lamplight by a flickering fire the hot water freed a metallic smell. Sometimes the hearth would be shared with a sickly chick or two on hay in an old hat and, almost inevitably, the wet nose of dog.

I slept at the back of the house. My bed overlooked changes of season in the middle field. Footprints and pawprints in overnight snow did not require Sherlock Holmes to deduce that Dad had been with Towser to feed the pigs. Manure heaps spaced with erratic geometry promised sweet green growth in spring; summer offered swathes of cut grass and, in autumn, leaves would be blown like brown paper bags against the top wall. At times the sky flashed with lightning, then growled with thunder, a barracking that found the ginger head underneath the bedclothes, ears pillowed, praying that the front door had been left open to let the thunderbolt out. None of us had met a thunderbolt so we wouldn’t have known what to look for anyway.

2

Parents

Don’t be too hard on parents. You may find yourself in their place.

Ivy Compton-Burnett

The farm was like a draught of spring water to a man who’d served an apprenticeship in the fumes of a town foundry with workmates in wide cloth caps and moustaches like Mexicans in the old westerns. Dad swapped the town fug for upland air but, unlike the foundry, the farm never closed. Between milk rounds he was at work somewhere on the land and a boy could always pester him to mend a bicycle puncture or give advice through a snowstorm of feathers, nails clenched in teeth, the steam bath from stable manure. He was a lean wiry Christian man with the assurance of belt and braces and a khaki smock with big pockets for the milk round. The Protestant faith had invested him with a quiet manner and voice, disciplined workstyle and oath-free language. I caught him out only once in our days at the farm when a barn door trapped his foot and tortured out of him a suppressed ‘damn’.

Young men of Salem Independent Methodist Church, 1915. Dad is second right, seated.

Smart bodywork – Dad, centre, in comic picture in Blackpool (1916).

Dad’s belt may have been a threat and, with braces in reserve, was available but it never touched me. Religion stopped it, I’m sure, though there was no Commandment against a leathering. Conversely, the mild man took to calling me Matey which I accepted as pally enough compared with the copper-knob, carrot-top and ‘has yer mother left yer out all neet’ of the schoolyard. Matey also had a Norsey feel to it and Norse was in some local names.

The family album lived in an old dusty suitcase under a bed and its contents suggested that Dad had patronised an Imperial Studio in the town several times as boy and youth, posing first in broad white starched collar and knee breeches, then with narrow collar and trouser turn-ups and once with thirteen chapel-going male friends uniformly well groomed in suits with waistcoats, polished shoes and partings right, left and centre, all a credit to the faith. It was a group at which Kitchener’s finger was pointing largely in vain as most were then too young for dispatch to the trenches though some, including Dad, saw service at home eventually. Those chic portraits of the farmer as youth did not chime in with my image of him later when responsibility and muck without bullets required him to get hands, face and clothes dirty.

He’d worked for a time at a wood yard where one of his duties was to fasten roller skates on to patrons of the firm’s rink. With a friend he also dabbled in cycle repairs and was cycling home one night when he fell foul of the law. The constable accused him of riding without front light and pointed to the alleged offender, one of the old carbide lamps. ‘It must have just gone out. It was lit when I set out.’ Dad offered truth from that honest chapel face. ‘I doubt it, son,’ the law said, and gave the lamp the finger1–touch test of the time. He burnt his fingers.

Though a lifelong abstainer from alcohol Dad had taken to smoking, perhaps in the Army, and developed a habit of docking a cigarette half smoked and pocketing the tab end for further reference. Whether that was his way of saving money or smoking less I never knew but the build-up of nicotine in the butts could not have helped his health in later years. A teetotal lifetime would be borne out by the fact that the only time I would see him walk into a public house would be for water – a canful for an overboiled radiator.

His work in Walton’s Foundry fitted him for minor repairs on the farm. His first name was Simpson, after his grandfather, and if called on to hump something heavy like a sack of provender to a hen hut he’d give a chuckle and quip ‘Hey, my name’s Simpson, not Samson.’ Some might have called him an improviser but many farmers had to be. They would ‘make do’ with odds and ends that lived around the place like heirlooms. ‘It might just come in handy, that.’ Some came in handy for my Christmas stocking, a home-made farm or garage perhaps, finished in paint left over from some other job. The family album had the three of us pictured on some promenade with Matey bowling along in a home-made buggy with two wheels and a single handle. Sawn-off bits of wood or broken stones came in for fencing or wall dentistry and as he plugged gaps against the bleak hillside it was a scene frozen in time, the make-do-and-mend of centuries.

Men of Walton’s foundry, Dad left, seated.

Wedding day, Mother and Dad.

The arms of both my parents seemed to be in perpetual motion as if, like the huge mill engines in town, once stopped they would take some starting up again. Hard graft was handed down. When Mother’s father died in the second year of the First World War his black-edged funeral card had the melancholy homily:

Wife and childen shed no tears

For hard I’ve laboured many years

I always strove to do my best

And now I’ve gone to take my rest

Travels by pushchair-Dad, Mother and Matey.

Sadly, he took his rest at forty, leaving a widow and six children. My mother, Mary Ann, the oldest at fifteen, had to help with the others and graduated in the Protestant work ethic which at Little Gib Hill she was practising further. Sometimes I would see her leave house or outbuilding with arms folded or in apron pockets as if on sabbatical. Much of the time they were plucking poultry, washing eggs, darning, sewing, raking ashes, mucking out, carrying buckets. Ironing had to be done with that inherited tip of spitting on the base of a hot flat iron to test its sizzle against the risk of singeing a petticoat. All the work was done thoroughly, as if for inspection. I, for one, could see no point in ironing handkerchiefs that would be opened up and blown on. By the time of Tum Hill I wiped my nose and tears myself and the trial of inviting me to spit on a hanky to dab facial smudges outside some non-smudge event had been abandoned. Her rite of hand-wetting my hair to smooth it down had a longer life.

Baking day was a weekly outing for nose, eyes and mouth, with rhubarb or apple pie, Quaker Oat biscuits, potato pie, scones and, after school, the honour of licking a spoon after use. Baked batter from flour, eggs and milk at times became Yorkshire pudding, an export to Lancashire which we copied without shame. Sad cake, a currant production, lived down its name by cheering us up. ‘Can I look?’ I’d say, with fingers everywhere. ‘They look with their fingers i’ Bacup,’ Mother would reply with a pretend tap on the wrist. I never knew why Bacup was so fingered. If a morsel of food fell on to the farmhouse floor she would assure me ‘it’s lost nowt’. My worry was whether it had gained anything. Toast was a favourite, especially topped with beans or sardines, signalled by the smell of the toasting fork rite over a red wound in the fire. Bilberry pie was the last act in some moorland excursion with Mother and Dad on hands and knees hunting the purple like bloodhounds in full sniff. Autumn pie-making and jam tomorrow followed prickly assaults on blackberry bushes before the mildew arrived. The plumpest were always out of boy-reach or hidden but the vision of the jam pan being hauled out of hibernation made up for the scratches and scrubbing out of purple stains from fingers.

Porridge was a winter chest warmer but another ‘p’, prunes and custard, a regular to keep you regular, would be too regular and make my adult years prune-free. Pancakes, tossed or otherwise, appeared on Shrove Tuesday or, as boys knew it, pancake day. Less appetising in Monday’s washday gloom, especially in winter with damp clothes on racks and maidens, was a fry-up of vegetables, survivors from the Sabbath, known as bubble and squeak. It might have sounded like an act on Palace billboards but never really entertained me.

There were some meals that a boy would eat readily until, with time, their slippery secret slipped out and he found he’d been consuming the lining of a cow’s stomach. It was called tripe, which suited it. The meal could be eaten cold or warmed with onions. Vinegar would gleam from tiny pockets in the honeycomb type eaten cold, and elder and seam varieties were also on offer; there was some concoction called tripe bits which must have come in cheaper. I remembered Auntie Martha on a tram with a parcel of tripe bits though whether they were for human or animal I easily forgot. Tripe would outlive the tram and had its own following in Lancashire. One of its supporters said it was mentioned by Shakespeare in one of his plays and by Dickens in a novel, which must have given it some sort of status on those market hall tripe stalls and in the cafés dedicated to its cause. Some of us were eating the foot of cow and pig, marked up as cow-heel and trotters, and liver and onions were also on the menu at Little Gib Hill.

Much of Mother’s working day was passed in a pinafore but she was amused to hear herself described as ‘a woman in a clean pinny’ in one of my school compositions, which did make it sound as if she sat around all day ‘doing nowt’. I also informed the teaching profession that our hens were not fed in wet weather, which showed an early tendency to fiction writing though even teachers in town would realise that such hens would not survive long in the rainfall shown on their weather maps of Lancashire. Weather watching was important to farmers. ‘Wind’s getting up,’ Mother would say as if it had been in bed all day. Then Dad would come back from the milk round and say that so-and-so’s ‘got wind up’ which meant having fear. Old men would ‘get wind’ and babies ‘get wind up’. As children we had much to learn, not least becoming familiar with that second language. Why, for instance, did it rain cats and dogs and not rabbits and foxes? Rain rain go away, come again another day, we used to chant, but nobody expected a shower of goats and pigs.

The path down the top field today.