8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

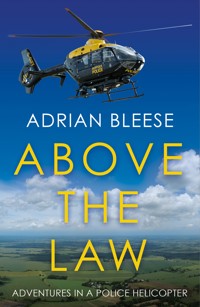

- Herausgeber: Eye Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Adventures in a helicopter Adrian Bleese spent twelve years flying on police helicopters, and attended almost 3,000 incidents, as one of only a handful of civilian air observers working anywhere in the world. In Above The Law he recounts the most intriguing, challenging, amusing and downright baffling episodes in his careerworking for Suffolk Constabulary and the National Police Air Service. Rescuing lost walkers, chasing cars down narrow country lanes, searching for a rural cannabis factory and disrupting an illegal forest rave…they're all in a day's work. It's a side of policing that most of us never see, and he describes it with real compassion as he lives his dream job, indulging his love of flying, the English landscape and helping people. Perhaps more than anything, it's a story about hope.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Published by Eye Books Ltd

29A Barrow Street

Much Wenlock

Shropshire

TF13 6EN

www.eye-books.com

Copyright © Adrian Bleese 2021

Cover by Ifan Bates

Typeset in Bembo and Century Gothic

The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Printed by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

ISBN: 9781785632624

The police are the public and the public are the police; the police being only members of the public who are paid to give full-time attention to duties which are incumbent on every citizen- Sir Robert Peel

Dedicated to all those who have given their duties any attention at all

Contents

Introduction

In The Beginning

Testing Times

Flying Over Nam (Chelt’n’am)

Different Views

Suffolk ’n’ Proud

JAFO

Wilkesy

Mispers

Seeing Is Believing

Just Another Day At The Office

Me and My Big Mouth

Weather and Cowardice

Mr Lewis

Still Waters

Firearms

Sex ’n’ Drugs ’n’ Rock ’n’ Roll

Technically Challenging

Captain Jack

The Fox and the Hare

Fairies, Blackies, Beatles and Bats

Sumac

With a Little Help From Our Friends

A Story of Country Folk

The Name’s Wallis, Ken Wallis

Here Be Dragons

Operation Headless

The Beginning of the End

Games People Play

The Notional Police Air Service

Ghost Of Its Former Self

My Last Spring Springs At Last

Clutha Vaults

Afterword

Acknowledgements

Also from Eye Books

Introduction

‘Cambridgeshire Police, what’s your emergency?’

‘I don’t know where I am and I think I’m dying.’

That was how today’s story started and it didn’t take long for those words to make their way to us, the helicopter crew. When the emergency phone line rings my heart starts to beat that little bit faster, I can feel the anticipation building. It’s a mix of excitement, knowing that in the next few minutes I’ll be airborne again, and apprehension, never sure if this is going to be life and death for someone. There’s no way of knowing what or where the next job will be: a car chase, an armed robbery, a drugs bust or a missing child. Today it’s Cambridgeshire passing on their concern for the welfare of the young lady who’d called 999 to say she was lost and dying.

I am lucky enough to be part of a crew of three with John Atkinson and Tony Johnson. That’s the standard crew of a police helicopter in the United Kingdom: one pilot, two air observers. Just about everyone knows what the pilot does, even most of the pilots, but the role of the air observer is, perhaps, not as clear. In a nutshell, it is the best job in the world. One of us will sit next to the pilot and assist with reading checklists and monitoring systems, that observer will also be responsible for using the camera to search for people and things, or record evidence when we reach the job. The other observer sits in the back of the aircraft, just behind the pilot, and navigates the aircraft to where we need to be. Once on scene, this observer will take tactical control of the helicopter and, quite often, all the other police resources assigned to the job. We swap around, one day in the front, one day in the back – not the pilot, the pilot always gets to sit up front, otherwise it gets a little bumpy. Today I’m in the front with John; Tony will be in the back.

All three of us know that a police helicopter is called to many jobs where speed of response is one of the most important considerations. Sometimes, though, particularly with missing persons, time spent on the ground planning what you will do when you arrive is invaluable. So, before we go anywhere, we do a lot of work with maps and the locations suggested by information we have received, looking at likely places within our search area, getting to know the lie of the land.

Once we are certain of our plan, we each grab our flying helmets by the chinstraps and head out of the office towards the blue and yellow Eurocopter EC135 sitting in the warm April sunshine on the helipad outside. John straps into the front right-hand seat and I strap into the left; the plastic and metal of the helicopter’s interior, gently heated by the sun, smells like a 1980s Ford Cortina. John and I run through the pre-start checks and he moves the switches to start the engines, there’s a high-pitched whirring before the jet engine lights and settles into a whistling whine as the rotors speed up to a blur above our heads. Tony then joins us, strapping in behind John and starting up his navigation equipment in the rear of the aircraft.

The air traffic control tower at Wattisham, where we are based, gives us clearance to taxi and John lifts the two-and-a-half tonnes of helicopter into the hover. Dr Johnson said that he who has tired of London has tired of life – but that’s because he’d never sat in a helicopter as it magically breaks its bonds with the earth; that’s the real test, and I could never tire of this moment. John moves us smoothly from the helipad to the fresh grass of the airfield and turns into wind. The ground just beneath my feet begins to speed up, faster and faster until the individual blades of grass are a smudge of green and we lift into the spring sky before heading west to help search for this young lady.

Around seventy per cent of the jobs we do entail some kind of search, and those for missing persons account for about a third of these. They are often the latest, and sometimes the final, chapter in a very sad story. This one is no exception. A string of bad luck had led this particular young lady to a point in her life where she was essentially homeless, relying on friends and sleeping on their sofas. When forced to rely on others and unable to see a way to help themselves, it is easy for good people to feel bad; she began to worry that she was a burden. She finally decided to take the few possessions she had and try to make it on her own. The last time anyone had heard from her was weeks earlier when she had left the last of those friends. That was until today when she rang 999 to say that she was dying and had no idea where she was.

We start our search of the areas that we’d identified back in the office but there are lots and lots of places where a person can be hidden in the twenty square kilometres our information suggested she was in. None of us are in the mood to give up easily and Tony calls her, gauging whether we are growing warmer or colder in our search by the noise of the helicopter in the background. After only about twenty minutes on scene we have narrowed the area down but still can’t find her and the battery on her phone has given up. John lands in a small clearing and, after he shuts the helicopter down, we continue the search on foot. It’s tough going, with low-hanging branches in our faces and brambles catching and tugging at our flying suits. But eventually we find her. She’s in a sleeping bag under a huge brambly bush the size of an elephant. She hasn’t eaten for several days and is far too weak to move. Even if she hadn’t been so weak, getting out of here would still be a real struggle; we can barely fight our way in to help her. While I talk to her and reassure her, John and Tony head back to the helicopter for the stretcher that we routinely carry but, thankfully, rarely use. After several minutes we manage to get her and her sleeping bag out of the undergrowth and onto the stretcher before carrying her to the helicopter and then, after a few minutes, on to an ambulance which has arrived at the end of a nearby lane.

I have no idea what happened to her after that and, several years later, I still wonder about her and dozens of others like her. I know that, thanks to Tony’s persistence and John’s flying skills, she didn’t die on that day. I hope, thanks to some of the training I’d had from the police and the things I was able to say to her, that she didn’t feel like dying any time soon afterwards. Perhaps just the fact that we listened to her helped. She called 999, so clearly she had hope for the future, she wanted to survive. Survival, above all else, needs hope. Perhaps this spring day was the start of a new phase of her life. I like to think that she’s happy today, but I don’t know for sure.

Fourteen years earlier I’d been asked a question in an interview for a job with the police; it was, I think, a very good question. An Inspector asked me, ‘How will you cope with the fact that you will be dealing with very intense incidents but may never learn the outcome?’ I bluffed my way through somehow and gave a reasonable reply but I didn’t really know the answer; we can never know who we will be until we’ve already had to be that person. As I’m a bit of a slow learner, I had to be that person for quite some time and it wasn’t until this April day – a few days before my forty-third birthday – that I really learned what he meant.

So, Inspector, to answer your question more fully, I’ll do what I can at the time in the very best way I know how. That way, most of the time, I’ll be able to forget the incident and move on to helping the next person. Sometimes, though, I won’t be able to do that and I’ll think about that person for a long time afterwards, maybe forever, because that’s the way life is. That’s okay, though, because I’ll know I’ve made a difference – and that’s what will make my work worthwhile.

I didn’t think of that at the time, mainly because I had no idea that this was the truth but partly because job interviews aren’t always the best place to think clearly. You have lots of memories to sift through in order to try to tell the story of who you are or, at the very least, who you’d like to appear to be. Sometimes that’s in the right order; sometimes it’s jumbled up; sometimes it’s relevant; sometimes it’s not; sometimes you forget what you meant to say, but every now and then it all works out fine. Life is like that, too, and everything is about stories. The stories that young lady told herself about the world and her friends and her own self-worth led to her nearly dying under a bush. The stories I told myself led to me being part of the team who stopped that happening.

These stories are, like all stories, a mix of fact and fiction; just one version of events. One thing you learn very quickly when you work for the police is that there are few things less reliable than an eyewitness. Memory is a liar and it is such a good liar that we generally believe it.

I wholeheartedly believe everything I’m about to say but I know that a lot of it isn’t the way that other people will remember it. Perhaps my story isn’t the whole truth but if it’s in any way a lie, then it’s one I’ll be completely honest about. Like all good stories there are car chases and murders and sex and drugs and rock ’n’ roll and, like all good stories, you shouldn’t believe all of it.

I’d like to tell you that story right now.

1

In The Beginning

I was born on a rainy Northern Tuesday in a hospital called Hope.

Although I was due to be a June baby, I could wait no longer than mid-April to get out and see the world; patience has never been a virtue with which I’ve been blessed. Back then, in the 1960s, it was a bad idea to be born six weeks early and weighing less than four pounds; people who did that were not too likely to see the 1970s. As a matter of fact, the doctors were not exactly full of confidence that I might make it to the next day, let alone the next decade, so I was baptised on my very first night in this world. I was my parents’ sixth child after sixteen years of marriage and I was the first one to be born alive, just about. I think they’d given up on the prospect of having children; I was something of a surprise. Having been the father of a premature baby myself, I know that the joy at their arrival is tempered by the heart-stopping, stomach-churning fear that they may not pull through. This fear must have run so very deep for my parents in the early hours of that spring day. A good job that the hospital was called Hope.

As you may have guessed, it went rather better for me than expected – so far I’ve seen 17,770 days, every dawn a bonus. The fact that I made it through the first few weeks is due, in no small part, to the staff in the Special Care Baby Unit at Hope Hospital, Salford. I have been told that there was a nurse, called Gilly, who predicted that I would one day be a six-foot, blond-haired, blue-eyed, piano-playing policeman. She may well have been in possession of psychic powers but it is, perhaps, more reasonable to assume that she was basing her foretelling of my future on my physical attributes. The blond hair and blue eyes were there already, as were the large hands and feet, like a puppy who has yet to grow into its paws, and I was quite long – as it’s hard to be tall in an incubator.

Today, my hair is mainly a memory, my eyes vary from grey to green to blue, depending on the day, and I can just about limp through ‘Chopsticks’ but I am six-feet tall and, as we shall see, she wasn’t that far out with her final prediction – and this certainly wasn’t the last time someone thought I looked quite like a policeman.

I have been six-feet tall for a very long time now, certainly since my mid-teens when my school uniform consisted of black trousers, a white shirt and a black tie. By this time I also had size-eleven feet and habitually wore Doc Marten shoes. Needless to say, none of this did anything to detract from my generally policeman-like appearance. As I made my way to school, shopkeepers would say, ‘Good morning, officer,’ thinking that I was a copper heading home after a long night-shift. This was not very flattering for a sixteen-year-old boy but it did make buying cigarettes and booze a lot easier, which eased the pain and made me more popular than may otherwise have been the case.

These instances of mistaken identity continued even after I’d reached an age where I could legally buy whatever I chose. On one occasion, in a dodgy nightclub in Lancaster, I was actually stopped from buying a drink as a friend and I were asked to leave because: ‘the locals don’t like drinking with coppers.’ He wasn’t a copper; nor was I. I was training to be an air electronics operator in the Royal Air Force, flying on Nimrod maritime patrol aircraft. I did that job for several years, operating radio, radar and electronic warfare equipment, hunting submarines and carrying out search and rescue missions. Unfortunately, I damaged my ears in a rapid decompression and the RAF decided that aircrew who couldn’t fly were surplus to requirements. They offered me enhanced personal leisure opportunities; that is to say, they asked me to leave. When I did, there were many who assumed I would forge a second career as a police officer simply because I looked like one. There can’t be many jobs where people do this: you don’t find eight-year-olds being bought sets of coloured pens for Christmas because they look like a graphic designer or seventeen-year-olds being advised on which degree course to take because they resemble a biochemist. I suppose that there is another career path which seems to depend on looks, though, and that is the criminal: looks a bit dodgy, eyes too close together, that sort of thing. Maybe it’s just cops and robbers who are selected in this way.

When I left the RAF I was stationed – and owned a house – in the far north of Scotland, in a village of one pub and about fifty houses called Dallas, reputedly the place from which the slightly larger, better-known, Texan Dallas got its name. I didn’t initially follow the physiology-based careers advice. In fact, I never followed any advice at all, and for a long time my career stuck fast to the second dictionary definition of the word, that is: ‘to move swiftly in an uncontrolled manner.’ I ran my own business for a while, taking photographs and creating brochures for hotels and tourist services, but the work was very seasonal so I sold double-glazing in the winter. In truth, I was too nice to be my own boss. I was twenty-four years old and single, there were many mornings when I didn’t feel up to going into work and others where the sun shone – even in Scotland – and I didn’t fancy working on such a nice day. My boss was very understanding; too understanding to make much of a profit. There wasn’t much else to do in that part of the world other than go out to the oil rigs or go fishing, so I decided to move. Being unmarried with no children and no real ties to anywhere at all, I could go wherever I chose. I closed my eyes and stuck a pin in a map, not metaphorically, but literally, with a real pin and an actual map of Britain. The pin landed in Bury St Edmunds, in Suffolk, so I sold my house, put my furniture into storage and drove to Bury St Edmunds to look for work and a place to live. I was soon lucky enough – following some time as a night porter in a haunted coaching inn – to land a job with the East Anglian Daily Times, creating advertising for local businesses.

However, a handful of years later, now a family man with three young children to help support and a couple of other jobs under my belt, I eventually found myself in that interview for a job with the police that I mentioned earlier. As I’d spent twenty-nine years unwittingly impersonating a police officer in my spare time it seemed obvious and entirely reasonable that I should take it up professionally. As you may have guessed by now, I passed the interview. The job I initially landed was that of control room operator – twelve hours at a time locked in a windowless room being the jam in the sandwich between the public and the police. I loved it.

Answering the telephones, including the 999 calls, and sending officers out to help. That’s what we all genuinely believed we did: we helped people, hundreds of times a day, to the very best of our ability. Some were the victims of crime, some the victims of circumstance, many the victims of their own brain chemistry, but we helped them all day long. There are few finer outcomes to achieve with your working day than to have helped someone. I was lucky to work with a marvellous team of people, all of them just a little bit odd in their own way, as just about everyone – and certainly anyone interesting – is when you really get to know them. Spending twelve hours in one room, often overnight, dealing with the most intense situations the population of Suffolk ever faced, meant that we got to know each other quite well. I was only there for a little over three years but I still have the card and the gift they bought me when I left and I still remember lots of the people and lots of the events we worked through together.

We were involved in the biggest incidents in people’s lives, often ones which changed those lives drastically. Most people who call 999 only have cause to do so once or twice in their entire life. They are often going through, or witnessing, one of the most traumatic incidents they’ll ever experience. We dealt with it a hundred times a night. Victims of domestic violence who have locked themselves in the bathroom, and really fear for their safety, screaming down the phone as you hear rage and splintering wood in the background. Those who’ve reached a point where they don’t want to go on but want to speak to someone, one last time, part of them clearly hoping that you can give them a reason to live, every fibre of your being trying to make sure you can. A young mum, calling you in the dark, empty hours of a Boxing Day morning because she’s just found her baby dead in his cot and has no idea what to do now. The dog walker who has just discovered a body and is in shock. All of these things, and so many more, stay with me to this day and I am proud that we were able to do a little something to hopefully change people’s lives for the better or, at least, ease some of the burden. I cherish the memories of long hours in that room, and of what we did there. I’m not here to tell you about those events, though, but to tell you about the events in the job I’d had my eye on since the first day I put on my white shirt and epaulettes. In fact, I had probably, subconsciously, been looking out for the job for years.

I left Salford when I was still quite young and grew up in a genteel seaside town on the Lancashire coast called St Anne’s-on-Sea. The bigger and better-known resort of Blackpool was its loud, brassy, show-off neighbour. When the holidaymakers had left and the illuminations were turned off, Blackpool often hosted political party conferences and, in 1985, Margaret Thatcher and the Conservatives came to town. The previous year’s conference had been in Brighton and the hotel used by the Tories had been bombed by the IRA, killing five people. Not surprisingly, then, security this year was tight and this was the first time that I remember seeing a police helicopter. I watched it circle the Winter Gardens and I wondered to myself, ‘How do you get a job like that?’ Thirteen years later I’d begin to find out.

My race to join the crew on the Suffolk Constabulary helicopter was not without its obstacles. The first – and some thought the biggest – impediment to my ambition was the fact that it did not exist; Suffolk didn’t have a helicopter. The neighbouring counties of Essex and Cambridgeshire did, but we did not. When we needed a helicopter we had to prove that it was worth the cost to all sorts of people with pips and crowns on their shoulders, who were generally quite grumpy at being woken up at 2am to be asked, so we often didn’t get a helicopter to attend our incidents – even when those events really, really deserved one. There were many things we had complete control over, hence it being known as the control room, I suppose, but there were a few things – generally things which cost money – that needed approval from a higher authority. And helicopters cost a lot of money. As is often the way with many things in life, other people’s helicopters cost even more.

I suppose it would be fair to say that, by the late 1990s, Suffolk was just a touch behind the times in this regard, given the fact that the first recorded use of an aircraft in support of policing took place in January 1914. A Curtis Model F flying boat, which had been offering pleasure flights for $10 to residents of Miami’s Royal Palms Hotel, was commandeered to help hunt down a steamer heading for Bermuda with the suspect for a jewellery theft believed to be on board. Apparently, the flying boat landed on the ocean next to the ship and a police officer boarded the steamer to apprehend the dastardly villain. While I was under no illusion that we might have jobs like that in Suffolk, I did feel we were lagging behind.

The usefulness of aviation to police forces around the world had been recognised fairly soon after that first incident. Charles Minthorn ‘Mile-A-Minute’ Murphy was, apparently, the first police pilot and first motorcycle cop, claiming these firsts just before the start of the Great War. He’d also been the first man to ride a mile on a bicycle in less than a minute; hence the nickname. There are also reports of the use of a Martin Tractor Trainer biplane by the San Francisco Police Department in 1916, though nobody is very clear on what for. It was just after the First World War that the first full-time police aviation unit in the world was formed – in New York City.

We in Britain weren’t too far behind, with the announcement in March 1919 of the formation of a British Aerial Police Force, though by the late summer it had been realised that we had neither the money nor the will to carry it through. We would have to wait for a while to see a national police air service, though we would never have either the money or the will to do it properly.

It is possible that the first British police air observer was flown by the Royal Air Force in an Airco DH4, two-seat light bomber, to keep an eye on the crowds and traffic at Derby Day at Epsom on 2 June 1920. It is certain that the R33 airship, registration G-FAAG, was requisitioned for the same use the following year, it even had radio communication with officers on the ground. The huge 643-foot-long silver craft must have been an incredible sight for race-goers as it motored at a leisurely pace overhead, powered by five 275hp engines, with its crew of twenty-six aboard.

The use of aircraft for Derby Day persisted through the 1920s and 30s with airships, tethered balloons, aeroplanes and even autogyros being used. An autogyro was used quite frequently by the Metropolitan Police. In fact a huge mural, still on a building in Cable Street in London’s East End, features the police use of the autogyro. This mural represents what was known as ‘The Battle of Cable Street’, which took place in October 1936 when tens of thousands of protestors, who were standing up to Oswald Mosley’s fascist blackshirts, clashed with police. Autogyros were, in many ways, the predecessor of helicopters. Kept aloft by an unpowered rotor, they have to maintain forward speed relative to the air and are powered by an engine driving a propeller in order to give them that forward speed. We’ll hear a little bit about autogyros later.

The first recorded use of a helicopter by a police force in the United Kingdom was on 15 June 1947 in the search for a fugitive in Norfolk, the county which is Suffolk’s northern neighbour. More than fifty years later Suffolk still didn’t have a helicopter of its own, so you can see why people thought my aspiration was something of a pipe dream. There were also those who felt that me being a civilian might be a bit of a hindrance, too, as civilians did not generally work as air observers on police helicopters.

Luckily for me our chief constable, Paul Scott-Lee (later Sir Paul Scott-Lee QPM DL) was on the case, and was very keen on civilianising any jobs that he could. He was the kind of leader who got involved and made decisions even when he didn’t quite understand what was going on, or so the story goes. Having finally made the decision to buy a helicopter – thanks in large part to the availability of a generous Home Office grant – he was now out and about, looking for ideas on how best to use it. One unit he visited took him for a flight, and when you’re flying a chief constable you don’t let any old copper accompany him as police constables have the unfortunate habit of sometimes telling the truth, particularly if they think they can get away with it. Nobody knows what might happen if a chief constable were to be told the whole truth, as it’s an experiment which has never been attempted, but it would possibly be very dangerous for all concerned. What they did, then, was to send their chief pilot and a crew made up of the unit executive officer and the deputy unit executive officer to fly with him, as they are more likely to be able to present an unambiguous and generally positive picture of operations to senior officers. They’d never actually lie, but it is just possible that they wouldn’t trouble him with some of the less fortunate facts.

As they flew along the Chief said, ‘So, you’re both civilians, are you?’

‘Yes, sir,’ they unambiguously chorused.

‘Does that cause any problems?’ he followed up.

‘No, sir,’ they answered positively, in unison.

‘Excellent, we’ll have a couple as well, then,’ Mr Scott-Lee informed them, his mind and my future made up.

Clearly they did not want to muddy the waters and confuse the Chief by pointing out to him that the unit executive officer had served for thirty years as a police officer and had retired in the rank of Inspector as head of the Air Support Unit, leaving on Friday in uniform and returning on Monday in a civilian suit. His deputy had had a similar career but had retired as a sergeant. Thankfully, these facts were not ones which they felt they needed to share, and my fate was sealed.

In the year 2000, Suffolk Constabulary took delivery of its helicopter and a year later Mr Scott-Lee’s civilianisation plans were put into action. It was, therefore, in the early summer of 2001, with three years working for Suffolk Constabulary behind me, that I found myself in one of a pair of police vans heading from headquarters at Martlesham Heath in Suffolk to the Royal Air Force Officer and Aircrew Selection Centre at RAF Cranwell in Lincolnshire. Many forces – before they got the strange and rather muddle-headed idea that they could do a better job themselves – used the services of the OASC to select their observers. The RAF had been selecting people for flying duties since its formation in 1918 and had trained hundreds of thousands of aircrew over the intervening years. They knew what to look for and who had the very best chance of not only passing the course but also being an effective aviator.

It was a warm morning and those of us who had written enough on our application forms to convince them to let us through the first stage of the selection process were sweating a bit in our best interview suits as we headed north and got to know our fellow candidates. I’m not sure I fancied my chances against the fast-jet navigator and army helicopter pilot and I’d pretty much told myself that I should give up, but luckily, as we know, I’m not the sort of man who listens to advice – even my own. Something told me that the young lady who spent the entire time on her mobile phone calling friends and saying, ‘Hee, hee, I’m in a police van,’ was not such a big threat but perhaps I was being unfair; she may have had a brain the size of a planet, the eyes of a young hawk and the reactions of a mongoose on cocaine. However, as this book is about flying on police helicopters and there were two places on the crew up for grabs and I don’t know her name, perhaps not. Sitting in the van with me, though I wasn’t aware of it at the time, was another man who was busy sizing up the competition. His name was Roger Lewis. He had no aviation experience but had worked for Suffolk Constabulary for about a dozen years as a driving instructor, teaching policemen to drive faster than is sensible without coming over all dead. It is just possible that we may see a little more of Mr Lewis later on.

2

Testing Times

Royal Air Force Cranwell, near Sleaford in Lincolnshire, is not only home to the Officer and Aircrew Selection Centre, where everyone hoping to join the service – either to fly or to hold the Queen’s commission – is tested to ensure they’re made of the right stuff, it is also the Royal Air Force College, where all new officers start their careers with six months of training. It was originally a Royal Naval air station before the formation of the RAF in 1918. Atop the red-brick and Portland stone neo-Georgian Baroque College Hall sits a small lighthouse, which may commemorate these nautical links. It should be noted, though, that the coast is twenty miles away, well over the horizon, even from the top of College Hall. So there is always the possibility that the lighthouse is there to remind officers how they should behave during their careers – it being both brilliant and of no practical use.

At RAF Cranwell we were seated in a huge room, lit only by the flickering bluish light of computer terminals. Each of us was in a little booth, screened from the next candidate and their terminal, not that there would have been time to glance over and cheat as test after test was introduced in quick succession. There was one where a stick man held a bat in one hand and sometimes faced you and sometimes had his back to you and occasionally stood on his head and you had to say which hand the bat was in. Then there were mental arithmetic tests where you left one point and headed so far in one direction then turned and went so far in another before you had to guess how far you’d gone in total. Others could clearly not be solved by humans but consisted of patterned cubes opened out and spun around and you had to say which was like the original cube. It is hard to remember all of the tests, as they rapidly bombarded us with one after another and the day passed in a tiring blur. I can only vaguely recall arriving back at Martlesham Heath headquarters and being told that I had passed. I can’t remember how many of us passed and I know that I should have been extremely pleased but my enthusiasm was tempered somewhat by the fact that this meant I had progressed to the next phase of testing: the fitness test.

I am not, by nature, what they call a gym bunny. I am built neither for comfort nor speed but rather more for sloth and the odd nap, so I was not looking forward to this next part of the selection. Of course I had trained, I’d been out running, dragged panting around the firearms training run by a helpful Inspector. I’d done press-ups and sit-ups and increased my chances of passing from embarrassingly poor to marginal at best. The day arrived in the sports hall at headquarters: press-ups and sit-ups and measurements and stretches and all sorts of other medieval tortures followed, all of which I passed, but then the morning’s trials culminated in the shuttle run. For this particular physical torment you had to run between two lines while beeps emanated from a tape recorder sitting on a bench at the side, which is probably where I should have been sitting, too. The beeps got progressively quicker and you had to reach the end of the course before the next beep, turn and head off in the opposite direction. Clearly an entirely pointless exercise. At least on the outdoors run with the Inspector we’d seen a little of the countryside before my vision blurred. I am pleased to say that I was not the first to pull out – not by quite a long way – but I didn’t pass; I didn’t reach the level required. I had failed.

Except, somehow, I hadn’t, I was told that I could progress to the next phase, the flight test, and re-run, quite literally, this part of the test if I was successful there. Well, the flying test was simple compared to this. I had flown aeroplanes and gliders as an air cadet, I had spent six years in the Royal Air Force as aircrew, my mate Graeme Thurtle had taken me flying over Suffolk three weeks earlier to get me back in practice. This I was looking forward to, but I was still just a little bit terrified, in the way that you are when you feel your entire future is at stake. As they say, anything worth doing is at least a little bit scary.

I arrived at Wattisham Airfield, the home of the Suffolk Constabulary Air Support Unit, very, very early, just to make sure that I had plenty of time to sit in my car and fret. After I’d done quite a lot of fretting about the upcoming test I swapped over to worrying about whether it was still too early to drive onto the base. I parked and went for a little walk to get some oxygen to my brain – just enough to allow it to agonise over whether I had walked too far and would now be late. Eventually I drove through the main gates and made my way round the airfield to the far side where the helicopter was based. It was quite a trek; the Army had clearly put the police as far away from themselves as possible. You turned right at the main gate, then left past the 1930s RAF guardroom and station headquarters – leftovers from the base’s previous life. Then came some hangars and officers’ married quarters and the pony club, before you headed out onto the airfield, following the perimeter track through woods and past relics of the Cold War. Even if you lived by the main gate you still had a long commute to work.

Chris Newman, who was a police constable air observer and the unit’s training officer, and Neal Attwell who was the deputy unit executive officer, which is helicopter-speak for sergeant, greeted me as I arrived, still a bit on the early side. Suffolk had the strange set-up that even though Neal was deputy, there was no one in the force to be deputy to. The Police Air Operators Certificate – our legal right to fly police operations, issued by the Civil Aviation Authority – was held, at this point, by Cambridgeshire Constabulary, and they had a unit executive officer who wasn’t, strictly speaking, our unit’s executive officer but he was the executive officer to whom our deputy unit executive officer reported. All clear? Good.

Chris outlined the flight test to me and gave me a chart (you get extra points if you don’t think this is a map, even though it looks just like one), a ruler, a protractor and details of a couple of locations that he wanted me to find, out to the south-west of the county. Perhaps the fact that I’d done this sort of thing dozens of times before gave me a slight advantage but it actually did little to calm me down.

I was strapped into the helicopter behind the pilot, Captain John Atkinson, who asked me if I could hear him on the intercom. When I said I could, he said to me, before anyone else could strap in, ‘Just enjoy it.’ I took his advice. I calmed down and enjoyed that flight. I don’t think it’s too much of a spoiler to say that I went on to enjoy 821 more flights with John, 820 of which he piloted. Not only was this first one enjoyable, I still remember it clearly. I recall Neal Attwell asking what the town passing down on our right-hand side was. I replied that it was Lavenham and he didn’t ask how I was so sure, so I didn’t tell him that when I first moved to Suffolk and worked for a newspaper in Sudbury, selling advertising to garages, one of my clients was a Peugeot dealership called Howlett of Lavenham and I thought I could just make out their garage on the corner of Sudbury Road and Melford Road. I’m not sure if I’d have been awarded extra points for that or not. From there it really couldn’t have been easier to find my target, in between the villages of Great Waldingfield and Acton (where I’d had another client) was a disused airfield which had been home to the Liberators and Flying Fortresses of the United States Army Air Force’s 486th Bomb Group in 1944 and 1945. Being a history geek – particularly aviation history – I knew all of this but didn’t share it, pretending that I was map-reading instead.

When we arrived in Sudbury I had to find one or two things. First the police station; that was easy – just down the road from the Barrett-Lee Nissan dealership on the roundabout. Then I was asked to find the train station; again, easy – just behind the Vauxhall dealership. Better frown at the map once or twice, though. Then John carried out a very tight spiral dive to the right while I was asked to count red cars in the car park. Nobody had told me that this was a manoeuvre designed to disorientate me, so I didn’t get disorientated. I was then tasked with finding Long Melford and pointing John in the right direction. Now this could have been more difficult, as I’d never had a client in Long Melford, but it did sit right between the Rodbridge Car Centre and Bull Lane Garage, and was an entirely unmistakable village, with two Tudor country houses and the huge Holy Trinity church – where Long John Silver was buried. So I did okay. A very enjoyable flight and I’d passed. They still needed me to pass the fitness test, though.

Next day I turned up back at the gym, alone and ready to give it my best shot but, obviously, no better prepared than last time, as I had still brought my Northern, pie-eating, beer-drinking, cigarette-smoking body with me, even if it was a couple of stone lighter than it had been four months earlier. I dreaded the thought of slogging up and down the gym to the ever-increasing rhythm of the beeps but, luckily and amazingly, Chris Newman turned up in shorts and ran alongside me, barely breaking a sweat, encouraging me and challenging me to do enough to pass, which I did. I’m not sure that I ever thanked him enough. I know that I couldn’t thank him immediately afterwards, as I was gasping for air and lying face down on the gym floor in a pool of my own salty sweat.

That just left the interview which, annoyingly, was arranged for the week that I was supposed to be away on holiday in the Lake District with my family. Fortuitously, I happen to be married to the single best and most supportive woman in the world, which is far more than I deserve. No, really – far, far more. She moved the holiday so that we went away the week before. As it happened that meant that we got a week of fantastic weather and had a great time. The following week, the week of the interview, when we should have been there, it rained torrentially the entire time. It was like monsoon season.

The day of the interview was extremely wet. However, for me, not quite as wet as expected because, when I went to have a bath I could coax only about an inch and a half of tepid water from the taps. I couldn’t worry about why just now – especially as, this being the summer holidays with three wonderful children and my delightful wife at home – I thought I knew the answer. So, in preparation for what might just have been the most important interview of my life, I had a cold and shallow bath. I put on my best suit – okay, my only suit, the one I’d worn to go to Cranwell – and I was ready to leave. My car, however, did not feel so inclined. A very old Volvo, it had decided that a trip to the Lake District was the final straw and it refused to move. In fact it wouldn’t even make a noise to suggest it was at least trying to start. It seems I had killed it. Still, I could borrow my wife’s little Citroën, and at least the rain had now stopped.

Halfway to police headquarters the rain started again and, this being a Citroën, I could not work out how to turn the windscreen wipers on because they always used to make it exceedingly difficult to find out how things worked in Citroëns. Nowadays you twist the indicator stalk or even have rain-sensitive wipers, but in those days you had to press an unmarked button while licking the driver’s side window and reciting the names of the seven dwarves, or something like that, to get them to work. The rain lashed down and my visibility extended little further than the windscreen. I had to slow right down as I peered out at the indistinct blobs of colour and occasional brake lights ahead of me and tried to remember Bashful’s name. Eventually I managed to coax some action out of the tiny wipers and made it to police headquarters alive. Given that I was soaked to the skin crossing the car park to the interview room, I can only conclude that I was given the job on a sympathy vote, but that counts.

Neal Attwell rang to offer me the position that same afternoon. I took roughly half a picosecond to think about it, to weigh up the pros and cons, and accept. You probably won’t be surprised to learn that the other candidate offered the job was one of those who we met in the van to Cranwell, driving instructor Roger Lewis. His nan was apparently quite surprised when he told her.

‘A new job?’ she asked.

‘Yes, Nan,’ Roger replied.

‘Flying on a helicopter?’

‘Yes, Nan.’

‘For the police?’

‘Yes, Nan.’ She’d clearly remembered all of the facts.

‘And how many applied for the job?’

‘Seventy-eight, Nan,’ Roger proudly told her.

‘Seventy-eight people and you got the job?’

‘Yes, Nan.’

‘And people said you were a bit thick.’

3

Flying Over Nam (Chelt’n’am)

Roger Lewis and I started our training to be air observers at the grandly titled International Police Air Training School (IPATS) which, as you may have guessed would be the case for such an illustrious place, was based at a major UK airport. Well, okay – Gloucester Staverton Airport.

On the evening of Sunday 14 October 2001, I picked Roger up from his home near to police headquarters and drove us to Gloucestershire. I mentioned earlier that Roger had been one of the force’s driving instructors and, as I needed to take a test to drive police vehicles, he took this opportunity to test me. If you know of anyone else who has had a 193-mile driving test then I’d be very interested to learn of it but, as things stand, I’m claiming the world’s record for the longest driving test in history. Luckily, as Roger is good company and a great storyteller, even a four-hour driving test is a pleasant way to spend a Sunday evening.

At the end of my test, which I assume I passed as he never mentioned a failure and I’ve driven a range of police vehicles since, we arrived at our home for the next two weeks: the Hatherley Manor Hotel. This is not the sort of place that the police normally pay for: a large, mostly red-brick seventeenth-century manor house, rumoured to have originally been built for an illegitimate son of Oliver Cromwell, Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland. I suppose that PAS – that’s Police Aviation Services, the company which ran the training under the name IPATS – was more used to finding a place for pilots to stay than for coppers, and pilots need to be looked after carefully and treated gently.

The old manor house sits in thirty-seven acres of gardens and grounds on a site which had been occupied for at least a thousand years. The manor and the lands around it were called Athelai in the times of Edward the Confessor and the prefix ‘Athel’ generally denotes a royal connection, often the property of a prince. You may never have heard of Hatherley Manor but I am certain you’ll have heard of, or even used, two things which were invented – or at least significantly developed – at this house.

In the mid-nineteenth century the house was owned by the three-times-mayor of Gloucester, Anthony Gilbert Jones. Jones had nine children and the seventh, his youngest son, Charles Allan Jones, is credited with the invention of the folding stepladder. Although stepladders had been invented in the United States twenty years before, nothing quite like Charles Allan Jones’ comparatively lightweight ‘Patented Hatherley Lattisteps’ had been produced. He set up a huge factory, the Hatherley Stepworks, in 1885. This covered two and a half acres and seems to have been a very early assembly line, with the steps carried through the factory on a tram system and each worker specialising in one part of the production process. The factory was heated by steam and lit by electric light generated on-site. To give some idea of the popularity of the Lattisteps at the time, the factory always tried to keep 15,000 in stock to meet demand. Along with folding tables and other wooden items, such as poultry houses, Jones may also have produced the recently patented deckchair. Some claim that he invented it; however the idea actually goes back thousands of years, even if no one patented it until 1886.