8,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Medina Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

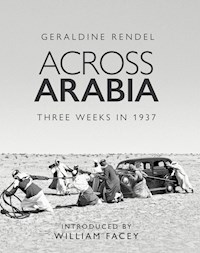

At the end of March 1937, Geraldine Rendel found she had achieved a trio of unintended distinctions. As the first Western woman to travel openly across Saudi Arabia as a non-Muslim, the first to be received in public by King 'Abd al-'Aziz, and the first to be received at dinner in the royal palace in Riyadh, she had joined a tiny coterie of pioneering British woman travelers in Arabia. Until the 1930s, a journey by any foreigner, male or female, across Arabia was a rare event. But when in 1932 the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia was proclaimed, increasing numbers of diplomats and oil company representatives began to make their way to its remote desert capital, Riyadh, aided by the arrival of the motorcar. With the car came the camera, and the pictures by the Rendels, both of them keen photographers, rank among the finest from the period. Geraldine's husband George, head of the Eastern Department of the Foreign Office, had been responsible for Britain's relations with Saudi Arabia since 1930. When he and his wife were invited to the Kingdom by King 'Abd al-'Aziz for a visit combining diplomacy with travel, he accepted with alacrity. The couple kept a detailed diary, on which Geraldine drew to write a lively account that she intended for publication. In contrast to her husband, who had serious political business to conduct, she treats their journey as a holiday. In the event her narrative, full of vivid social encounters, humor and insights into the women's side of life, failed to appear in print, and is published here for the first time. Combined with the couple's striking images, this book presents a unique picture of Saudi Arabia on the verge of modernization. William Facey's biographical introduction interweaves the story of Geraldine's adventurous life with the evolution of Anglo-Saudi relations in the 1920s and '30s, so placing the Rendels' trans-Arabian journey in its political context.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 392

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

ACROSS ARABIA

ACROSS ARABIA

THREE WEEKS IN 1937

Geraldine Rendel

Photographs byGeorge and Geraldine Rendel

Biographical introduction byWilliam Facey

Across Arabia

Three Weeks in 1937

Text ofArabian Journey: Three Weeks Crossing Saudi Arabia

by Geraldine Rendel © the Rendel family

Introduction and notes © William Facey/Arabian Publishing Ltd 2018

Produced and published in 2021 by

Arabian Publishing Ltd

www.arabian-publishing.com

a division of Medina Publishing Ltd

www.medinapublishing.com

Editing and picture research: William Facey

Design: Kitty Carruthers

Additional research: Frances Topp

Maps: Martin Lubikowski, ML Design

Printed and bound in Turkey by Imago

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owners.

A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-0992980856

FrontispieceGeraldine Rendel inca. 1940, shortly after her Arabian journey.

The pearl necklace is perhaps one of those given to her by the Saudi royal family in honour of her visit (see p. 208 n. 94: p. 212 n. 156).

I stepped off the quay into the boat feeling that adventure had begun. I was walking right out of my life into another of which I had no real conception, and the present alone had reality. I had passed through a magic door and it had shut behind me setting my fancy free. My everyday world grew dim; it was like slipping into another dimension and finding surprisingly that one fitted in.

Geraldine Rendel (see below, p. 64)

CONTENTS

Foreword and acknowlegements

Maps

Introduction

Through a Magic Door: The Life and Travels of Geraldine Rendel by William Facey

Geraldine Rendel: birth and background

A young diplomatic family

Britain and the Arab world between the wars

Saudi Arabia in the 1920s and ’30s

First Middle Eastern journey, 1932

Britain and Saudi Arabia, 1932–36

The Rendels’ 1937 Middle Eastern journey

Anglo-Saudi tensions, 1937–39

The Rendels: the Second World War and after

George and Rosemary Rendel visit the Kingdom, January 1964

Arabian Journey: Three Weeks Crossing Saudi Arabiaby Geraldine Rendel

Foreword

1From Basra to Kuwait

2Bahrein

3From Bahrein to Hasa

4Hasa Oasis

5From Hasa to ‘Uraira

6To Rumaya

7Arrival at Riyadh

8With Amir Saud in the Palace at Riyadh

9Riyadh to Duwadmi

10Qai‘iya, Afif, Dafina, Muwaih and Ashaira

11Taif

12To Jidda to Meet the King

13The Queens’ Palace at Jidda

14Departure

Notes

Sources and References

Picture credits

Index

FOREWORD AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

IFIRST CAME ACROSS George and Geraldine Rendel in 1986, while carrying out research for my book,Riyadh: The Old City. David Warren, then in charge of the photograph archive at the Royal Geographical Society in London, drew my attention to two grey boxes, marked G9, on the shelves. These, he said, might contain items of interest. To my surprise and delight, they contained an excellent series of photographs of Riyadh, among many other images taken during a journey by the Rendels across Saudi Arabia in 1937. It turned out that they had been deposited in 1982, together with their original negatives, by the Rendels’ younger daughter, Rosemary, with whom I then made contact. A dozen or so of the historic images of Riyadh were published inRiyadh: The Old Cityin 1992. Subsequently, in 1998, I sorted through all the Rendels’ Saudi Arabian images, which turned out to be more than 280 in number, matching negatives to prints and amplifying the Rendels’ caption information. This new catalogue I shared with the RGS, with no particular expectation that it would come in useful again.

The Rendels’ photographs are of striking historical importance as a graphic record of Saudi Arabia on the brink of modernization. Both Rendels were excellent photographers with an acute visual appreciation of their surroundings and a natural eye for composition. So vivid and coherent is the sequence of images of their journey that I had often thought of it as a collection in search of a publication. Imagine, then, how exciting it was in 2017 when a grandson, Jonathan Rendel, sent Medina Publishing a hitherto forgotten travelogue by his grandmother Geraldine, entitled ‘Arabian Journey: Three Weeks Crossing Saudi Arabia’. Might we be interested in publishing it? A quick inspection was enough to confirm the quality and interest of the lively and elegantly written 39,000-word text. The chance to combine her travelogue with the photographs of the trip, and to set both in the context of the Rendels’ lives and of Anglo-Saudi relations in the 1930s, was one not to be missed. The result is this book, in which text and image amplify and complement each other in a remarkable and satisfying way.

Above all I would like to thank Jonathan Rendel for offering Geraldine’s text to us. This would not have happened without the suggestion of our mutual friend, the Arabist Dr Peter Clark, to whom Jonathan had happened to show Geraldine’s typescript and who immediately spotted its significance. Peter thus qualifies for equal gratitude. Further thanks are due to Jonathan and Christopher Rendel for entrusting me with the editing, notes and biographical Introduction, and for providing pictures, documents and genealogies from their family archives, and also to Philip Rendel for his interest and co-operation.

Joy Wheeler, of the Royal Geographical Society’s Picture Library in London, deserves special thanks for giving me renewed access to the Rendels’ photographs and fielding my constant enquiries. I am also grateful to Alasdair Macleod, Head of Enterprise and Resources at the Royal Geographical Society, for permission to publish them. And, as ever, I owe a debt to Eugene Rae, Jan Turner and Julie Carrington for their all-round helpfulness in the excellent RGS library.

Piecing together what little could be found on Geraldine’s life and background would have been impossible without information from Jonathan and Jane Rendel and their cousin Lindy Wiltshire. They were refreshingly open to the debunking of family myths and shared many memories of conversations with their aunt, Rosemary Rendel. Jonathan Rendel spared me much inconvenient legwork by making available copies of the relevant Rendel papers deposited at the National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth. Others too contributed to my account of Geraldine’s life: Peter Clark, who also alerted me to Elie Kedourie’s assessments of George Rendel in hisIslam and the Modern World, and provided useful pointers to the family of Lucy Wickham of Frome, Geraldine’s mother; Prof. Troy J. Bassett, of Indiana University-Purdue University Fort Wayne, who first put me on the track of the novels of Gerald Beresford FitzGerald, Geraldine’s father; and my wife, Marsha, who provided much perceptive literary criticism based on a reading of some of these novels, as well as insights into Geraldine’s background and character.

Frances Topp carried out useful documentary research at the National Archives of the UK at Kew into, among other things, the papers of Sir Colin Crowe, Sir George Rendel’s friend, fellow-diplomat and UK ambassador to Saudi Arabia during 1963–64. Debbie Usher at the Middle East Archive, St Antony’s College, Oxford, kindly gave me access to the forty-one colour slides of Sir George and Rosemary Rendel’s visit to Saudi Arabia in 1964. My thanks to both.

It will come as no surprise to biographers that some avenues of research led to dead ends. Most notable was my vain attempt to establish whether Mount Offaly House in Athy, Co. Kildare, had ever been in the possession of Geraldine’s branch of the FitzGerald family. I am none the less grateful to the Revd Olive Donohoe of Athy, and to Margaret Walsh and Clem Roche of the Athy Heritage Centre Museum, for putting up with my tiresome enquiries and going to the trouble of investigating the history of the house. Warm thanks to all.

Presentation of the text

The text of Geraldine Rendel’s typescript is published here word-for-word, without abridgement. The very few editorial interventions are confined to the addition of the chapter titles (using her spellings of place names), correction of a very few obvious typographic errors, and some adjustments to the punctuation. The author’s sometimes eccentric spellings of Arabic words and names have been left in the text as she wrote them, and are identified and presented in a properly transliterated form, where desirable, in the notes and index. In the Introduction and picture captions and on the maps, Arabic words and names are presented in the same transliterated form, but shorn of macrons and diacritics.

William Facey Arabian Publishing London, 2020

Geraldine Rendel enjoying the sea air on board a British steamer in the Gulf, February 1937.

INTRODUCTION

Through a Magic Door

The Life and Travels of Geraldine Rendel

AT THE END OF MARCH1937, having crossed Saudi Arabia with her husband, Geraldine Rendel found she had achieved a trio of unintended distinctions. As the first Western woman to travel openly across the Peninsula as a non-Muslim, she had joined Lady Anne Blunt, Gertrude Bell, Rosita Forbes, Freya Stark and Lady Evelyn Cobbold in a tiny coterie of pioneering British women travellers in Arabia. She had also become the first Western woman to be received in public by King ‘Abd al-‘Aziz Ibn Sa‘ud, and to be received at dinner in the royal palace in Riyadh.

The Rendels’ visit to the Kingdom was a semi-official one, and Geraldine had played no part in its planning. Its chief aim was to enable her husband George, at the time head of the Eastern Department of the Foreign Office, to familiarize himself with the new Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and to hold face-to-face discussions with its monarch. In those days, personal relationships played a vital part in the conduct of Anglo-Saudi diplomacy. The Saudis invited George to bring along his wife, and organized the visit in such a way that official business could be combined with the pleasures of travel and social encounter. It was a trip that clearly appealed to Geraldine’s adventurous nature. Her interest and excitement are palpable on every page of the handwritten diary she and George kept and, on her return to England, she set about typing up a more polished version that she intended for publication.1In the event, her husband felt, perhaps for reasons of diplomatic confidentiality, that this typescript should not be published in full, and Geraldine was only able to put into print a short, illustrated article that appeared in theGeographical Magazineof 1938. The full version languished for decades in a folder, more or less forgotten but, happily, preserved by the family. The only book that Geraldine ever wrote, it is published here for the first time.2

A striking quality of the Rendels as travellers is that they were both excellent photographers with a natural eye for composition. Unlike Geraldine’s text, their photographs have been known about since they were deposited at the Royal Geographical Society in London in the early 1980s.3Their images of Persia and Arabia in the 1930s are of outstanding historical importance. The rediscovery of Geraldine’s travelogue created a wonderful opportunity to marry it with the Arabian sequence of pictures and, as presented here, text and image illuminate each other in a way that was previously impossible. We are fortunate to have such a vivid depiction of Saudi Arabia on the cusp of modernization.

Geraldine’s crossing of Arabia prepared the way for the very similar one made the following year, in the opposite direction, by HRH Princess Alice, Countess of Athlone, whose journey attracted much greater publicity.4Though another Englishwoman, Dora Philby, had been driven across Arabia in 1935, unlike Geraldine she had not been able to travel openly as a non-Muslim. Dora’s journey had been made with her husband, Harry St John Philby, who had converted to Islam in 1930, and she had been treated accordingly as a Muslim wife, being confined to the women’s quarters in Riyadh. Geraldine, by contrast, though obliged to wear a veil when among Arabs, was allowed much greater social freedom.5The progressive easing of the customary restrictions under which these three women were able to travel is a measure of how quickly central Arabia was opening up to access by foreigners during the 1930s.

Geraldine and George in Kensington, on their wedding day in April 1914.

In 1937, the Rendels had been married for twenty-three years and had raised four children.6Geraldine was fifty-three, four years older than George. Their wedding on 21 April 1914, just a few months before the outbreak of the First World War, had been a hasty one. George, a young diplomat back from his brief first posting in Germany, was just embarking on his career. The Diplomatic Service preferred its recruits to be single and, when George announced his determination to marry, he was abruptly transferred from Berlin to Athens. He seized his brief moment in transit through London to arrange the wedding, a Catholic ceremony conducted in the lady chapel of Westminster Cathedral.7At twenty-nine, Geraldine was old for a bride in those days; nor, as we shall see, had she been brought up as a Catholic. Such obstacles clearly point to the couple having married for love. George’s admiration for his enterprising, artistic and sociable wife seems never to have waned: he expresses it with obvious sincerity whenever he mentions her in his memoirs.8

George William Rendel (1889–1975) would go on to achieve great distinction in the foreign service. He was born into a notable Victorian engineering dynasty, his father being the eminent naval designer George Wightwick Rendel (1833–1902), manager of Armstrongs and, latterly, a civil lord of the Admiralty. George Wightwick had married his second wife, Licinia Pinelli (1846/47–1934), in Italy, while serving on a design committee for the Italian ministry of marine, and had three sons by her.9George William was thus half Italian and was brought up as a Roman Catholic. He was sent to school at Downside, the Benedictine abbey and boarding school in Somerset, and would remain a devout Catholic for the whole of his life.10

Capable and clever, with a flair for organization and a fluent mastery of French and Italian, he graduated in modern history from The Queen’s College, Oxford, in 1911, and fixed his sights on a career in diplomacy. By then he had probably already met his future wife on the Isle of Wight, where the Rendels had a home at Sandown.11Geraldine happened to be living on the other side of the island, by Totland Bay, having been compelled by adverse family circumstances, as we shall see, to take employment as secretary to the Wards, a prominent Catholic family. The spacious and stylish Ward residence, Weston Manor, still preserves the beautiful private chapel designed by the Catholic architect George Goldie, with a fine interior by Peter Paul Pugin. According to Rendel family tradition, it was in this setting, at once religious and romantic, that George proposed to Geraldine.12

Geraldine Rendel: birth and background

Geraldine Elizabeth de Teissier Rendel (1885–1965) was born in Kensington, the third of five children of a minor Victorian novelist of Irish descent, Gerald Beresford FitzGerald (1849–1915).13Her father, henceforth referred to as GBF, belonged, as George Rendel records, to a branch of the FitzGeralds of Kildare which “had long been established in England”.14

According to family tradition, Geraldine and her two sisters were born not in England but in Dublin where, allegedly, GBF sold his tumbledown Irish castle to finance moving to London to educate his daughters and marry them off.15This may preserve a memory of some such event elsewhere in the family, but the truth was more prosaic. GBF was born in 1849 in Southampton, the only son of the Revd Gerald Stephen FitzGerald (1810–79), Anglican curate of All Saints church, and his wife, Susan Anne née Beresford, of the Lord Decies family of Waterford and Kildare.16Despite the Irish connections, there is no evidence to show that either GBF or his father ever lived in Ireland. GBF’s father went on to become vicar of Highfield, a suburb of Southampton (1852–64), and then rector of Wanstead, in north-east London. The 1871 Census shows the family to be in residence in Wanstead, so he was not an absentee cleric, as was commonly the case in those days.

A portrait of Vice-Admiral Sir Robert Lewis FitzGerald, Geraldine’s great-grandfather.

GBF’s grandfather was Vice-Admiral Sir Robert Lewis FitzGerald (1766–1844), who was buried with other members of his family in Bath, Somerset.17GBF’s branch had thus been based in England for some time, while maintaining their Irish connection. The FitzGeralds as a whole could cite a long and distinguished pedigree in Ireland extending back to the early 12th century, when their Norman-Welsh ancestors had conquered swathes of Irish territory. Over time, they became deeply assimilated into the local Irish aristocracy in which, as Lords of Offaly, Earls of Kildare and Desmond and, later, Dukes of Leinster, they would play a notable role in Irish history.18By the 19th century, the FitzGeralds were well embedded in the dominant Anglo-Irish class known as the Protestant Ascendancy.19It might certainly have been possible, therefore, for FitzGeralds based in England to provide for their advancement in society by selling property in Ireland. However, we have no evidence to corroborate the dubious family story that this was the case with GBF.

Outwardly, GBF was destined for the life of conventional Victorian respectability that typified the upper-middle-class FitzGeralds. At eighteen, he went up to Oxford: he is on record as having been at Balliol College in 1867–68, at a time when his father is listed as being ‘of Southampton’. His tutor was ‘B.J.’, who turns out to be no less a figure than the celebrated classicist, theologian and university reformer Benjamin Jowett, who would become Master of Balliol in 1870. Why GBF lasted only a year in this exalted academic sphere is not recorded. One may speculate that he owed his place at Balliol to the influence of his father’s younger brother, Revd Augustus Otway FitzGerald (1813–97), Archdeacon of Wells Cathedral in Somerset, who had himself entered Balliol in 1831. Geraldine would later recall this man as her great-uncle. It may also be significant that in 1867, the very year that GBF went up, the Archdeacon’s son and GBF’s first cousin, Gerald Augustus Robert FitzGerald, was elected a Fellow of St John’s College, adjoining Balliol.20

For reasons unknown, GBF failed to sit his exams and obtain a degree. He next took a government job in the Home Office in London, where he worked as a clerk between 1869 and 1881. We do not know what exactly his job entailed, but his fellowships of the Royal Geographical Society, Royal Historical Society and the Society of Antiquaries testify to wide and cultured interests outside his employment.21More significantly, he was embarking on what he was clearly coming to regard as his proper career as a novelist. His first two works of fiction were published in the 1870s:As The Fates Would Have It: A Novel(1873), andLilian: A Story of the World(1877).

GBF’s father died in 1879 and, shortly after, his life took a dramatically different turn. It is not known whether his father left him anything, but in 1880 his wealthy and childless paternal uncle, Charles Robert FitzGerald, a resident of Marylebone, also died, bequeathing his nephew £50,000.22Whether or not GBF was expecting this windfall, the acquisition of such a sum – the equivalent of almost £6 million today – was life-changing. He very soon landed a bride, and gave up his employment.

His wife-to-be was Lucy Adelaide Wickham, daughter of Francis Wickham of Frome, in Somerset.23The Wickhams were a prominent local Tory family of well-to-do lawyers and Anglican clerics. The Somerset connection again points to the influence of GBF’s uncle, the Archdeacon of Wells. The couple were married in January 1881. Two sons and three daughters followed between 1882 and 1888 including, in 1885, Geraldine. Now a wealthy man, GBF would have had no need to sell property in Ireland, if such existed, to fund the upbringing of his children and their entry into society. He installed his growing family in a stylish part of London: Geraldine was born in South Kensington, and in 1904 he gave his addresses as 63 Eaton Square, Belgravia, and Rosary Gardens, South Kensington. He then set about conjuring up a literary career. Between 1881 and 1904 he produced a string of eleven more novels, with titles such asClare Strong,An Odd Career,A Fleeting Show,The Fatal Phial, andThe Minor Canon.24As contemporary social fiction, these narratives quite obviously draw on GBF’s own background and life, and so are of interest insofar as they shed light on the lifestyle, attitudes and expectations amongst which Geraldine grew up.

Their author intended his novels as popular fiction aimed at an educated female readership, and seems to have funded their publication. Though written with a certain patrician panache, they are slight productions, marred by slipshod construction, abrupt transitions and inconsistent characterization, as if dashed off in a hurry. These days they languish unread and unregarded, even by the family, but the Victorian market for melodrama ensured a more positive reception. In 1899, a reviewer in a highly respectable journal such asThe Scotsmancould describeBeyond These Dreamsas “a powerful story, [which] should confirm its author’s reputation as a strong and clever writer”. As forClare Strong, it commended the “personal observation of a thoughtful, candid and cultured mind”. TheAthenaeum, theMorning Post, theIllustrated London Newsand theGuardianall chimed in with favourable reviews.25

Clare StrongandAn Odd Careerare typical, being set among the London upper-middle class of moneyed professional and military men with access to country seats. Many of the characters have names common in Ireland.26The stories are driven by themes such as the nature of success and the life well lived. These and inheritance, wealth and class, the shame of illegitimacy, and political ambition and patriotism are the focus of much high-minded philosophizing. However, the most frequently recurring narrative thread in the books is a preoccupation with marriage, with an emphasis on the differences between men and women and what they want out of life. Clare Strong, for example, is a well-to-do, cosmopolitan young man in search of matrimonial fulfilment. GBF’s last novel,The Marriage Maze: A Study in Temperament, was published in 1911 – around the time when Geraldine and George first met – and is an exploration of the ingredients of a satisfactory union. On this score, the author is generally a pessimist, even a cynic: “What we all desire to explore, and so many are anxious to find a way out of,” reads the epigraph. The story is a melodrama of miscommunication; just as misunderstandings are resolved and relations restored, tragedy strikes in the person of a drunken Irish chauffeur, and the wife is killed in a car accident. The widower, by now an MP, is left to bring up their baby in “the joy of perfect love” for his deceased spouse – only attainable, so the message seems to be, without the inconvenience of an actual woman on the scene.

A young Edwardian: Geraldine in the decade before the First World War, perhaps aged about twenty.

The central character inAn Odd Career, Sir Roderick Damer, perhaps represents an ideal of what GBF himself would have liked to be. Damer lives a comfortable bachelor existence, away from the annoyance of “a wife with whom you have no sympathy [and is] always with you”. He is able to enjoy the best of everything and to indulge his taste for books and original works of art. He combines an agnostic outlook with lofty moral views about social inequality, snobbery, self-denial and wasted lives. The chapters open with philosophical quotations from English and Latin writers, and in one case even from the ancient Greek poet Anacreon. However pretentious one may judge these to be, they are at least evidence that Geraldine was brought up in a highly cultured household. Apart from this, we have no record of her education. Nor is there any direct evidence about her parents’ relationship, though GBF’s views on marriage suggest that it was perhaps not an easy alliance. The fact thatThe Marriage Mazewas written in collaboration with a young Irish author still in her twenties, Olive Lethbridge, is perhaps a symptom that all was not well.27

Alas, GBF’s pursuit of a literary reputation brought him neither fame nor fortune. He later claimed to have made a loss totalling £440 from his publishing efforts.28His lavish lifestyle was intended, according to his descendants, to confer social status on his family, provide a good education for his children, and attract suitable husbands for his daughters. But he was funding this costly project by frittering away his capital – a lack of realism that suggests an improvident, even feckless, nature. Despite acting as executor from time to time for other deceased connections, and no doubt thereby gaining some financial benefit, by 1904 he had tumbled into insolvency.29His petition for bankruptcy attracted some gleeful attention in the press, under such headlines as ‘A Novelist’s Extravagance’, and ‘Vanished Fortune’. TheLondon Evening Standardof Friday 10 June 1904, for example, reported as follows:

Court of Bankruptcy (before Mr Registrar Hope) A Novelist’s Expenditure

Re G.B. Fitzgerald – This was a sitting for the public examination of Gerald Beresford Fitzgerald, who filed his own petition describing himself as of Rosary-gardens, South Kensington, of no occupation. The statement of affairs showed liabilities amounting to £8,355 10s 7d, of which £2,483 10s 7d were returned as unsecured, and an estimated surplus in assets of £923 11s. – The Debtor, prior to 1880, was a Civil servant, and he states that since then he has had no occupation except that of novel writing. It appeared that the Debtor, under the will of a relative who died in 1880, became entitled to £50,000, of which he brought £10,000 into an ante-nuptial settlement, and had gradually expended the balance. He estimates that his household and personal expenditure since the 22nd April 1901 has amounted to £11,072. – In reply to the Senior Official Receiver, the bankrupt acknowledged that his failure was due to extravagance. He had kept up a considerable establishment, and estimated that his expenditure during the last three years had amounted to £3,690 per annum. His creditors included £526 for ladies’ millinery; tailors and hosiers, £181; wine merchants’ accounts, £425, &c. He had, therefore, lived in good style.

Reporting on the same day, theGlobeconfirms that since 1880 he had had “no occupation except that of novel writing”, while theMorning Postgoes into more detail on his spending and the reasons for it:

Soon after coming into his fortune, he, on marriage, settled £10,000, with life interest to himself, from which an income of about £400 a year was received. … His failure was due to extravagance, but not personal extravagance; he having a wife and large family to bring up. The securities forming the balance of his fortune he had realised from time to time, and had lived on the proceeds. He had lost nothing through betting or gambling.30

The FitzGerald family fortunes plunged to their nadir with the sale in July of the household effects of 63 Eaton Square, among them “walnut, satinwood and ash bedroom suites, brass and iron French bedsteads, … a carved oak dining-room suite, handsome ebonised and ormolu-mounted china cabinets, Chesterfield couch, settees &c., easy and arm chairs, oil paintings and engravings signed by Sir F[rederick] Leighton, coloured engraving by Thomas Landseer”.31

How humiliating this social and financial disaster must have been for his family can only be imagined. The blow would have been softened slightly by the fact that the £10,000 in trust for his wife would have remained inviolate, giving the family some £400 per annum (equivalent to £45,000 today) to live on. His daughters’ marriage prospects would have nosedived, however, though there was one minor success to report: Mary Susan’s wedding to a much older man, on 22 January 1906.32Geraldine would have to wait until her late twenties, in those days deemed very late for a young woman.

GBF eventually moved into a flat in Kensington where, in 1915, he died at the age of sixty-six. His wife, Lucy, would outlive him by almost thirty years.33Geraldine later recalled how her father had been unable to cope with his reversal of fortune and, bizarrely, failed even to fully appreciate the reasons for it.34Certainly it had been a sharp lesson in the precariousness of life, but it seems to have had the opposite effect on his independent and practical daughter, who clearly found much in her father’s character to react against. Realizing that she would need to rely on her own resources, she looked for a job, and found employment as secretary to the Wards on the Isle of Wight. Her choice of employer suggests that she was already drawn to Catholicism before she met George Rendel who, up to 1911, would have been spending some of his Downside and Oxford vacations at home in Sandown.35Exactly how or when they met is a matter of speculation, but most probably it was through mixing in Catholic social circles on the island. Above all, she had met a man who, as her husband, would appreciate her qualities and greatly value her as his life’s companion.

Broadlands, the Rendel home at Sandown on the Isle of Wight, where the young George Rendel would have spent his vacations from school and Oxford.

A young diplomatic family

In April 1914, the newly-weds went straight off to George’s new posting in Athens, stopping only for a day at his mother’s villa on the Riviera.36Geraldine would play a very supportive part in her husband’s diplomatic career, joining him whenever possible and juggling her travels with the need to provide a home and education for their four children in England. She picked up languages quickly and had an easy sociability, whether among peasants or diplomats and royalty. But she also undertook difficult and dangerous assignments on her own initiative, bearing them with a fortitude that belied her somewhat fragile physical appearance. She showed her taste for adventure from the very beginning of married life in Greece, going on lone, intrepid excursions to hike or sketch ancient ruins. She seems to have been undaunted by hardship or the gruelling conditions of life abroad during the war.

Geraldine indulged her taste for adventure by taking arduous holidays in Greece. Here she is shown travelling in Crete in 1915.

In 1916, she went by sea to Salonika with Princess Demidoff to help organize camps for Serbian refugees. This was perhaps an adventure too far, for at the end of that same year, back in an almost equally dangerous Athens, she lost her first baby.37Soon after, George was posted to Rome, Lisbon and then Madrid, where their eldest child, David, was born in 1918. In 1919, George was sent briefly to Paris, where his talent for organization was put to good use in overhauling the embassy filing system. For safety, he left Geraldine on the Franco-Spanish border at Hendaye. She had been carried there, undaunted as always, by mule for part of the way, while still nursing her six-month-old baby.

A studio portrait of Geraldine taken in about 1914.

After two enjoyable Iberian years, the Rendels were happy to return home to find that, in the first of several reorganizations, the Diplomatic and Foreign Office Services were being merged. George took the opportunity to transfer to the Foreign Office in Whitehall, enabling the couple to set up home in London, where they would spend the 1920s and ’30s. Their first home was at 25 Draycott Place, Chelsea, and three more children followed in due course – Anne (1920), Rosemary (1923) and Peter (1925). The family albums are full of happy holiday snaps taken in France and at south coast resorts such as Eastbourne and Swanage. As they grew up, the children would be sent to prominent Catholic boarding schools – the boys to Downside, the girls to St Mary’s, Ascot.

Early married life in Greece: George and Geraldine relax over tea on the terrace of their Athens house in 1915.

Geraldine makes her way to Hendaye with six-month-old baby David in a donkey pannier.

George spent the 1920s working in the FO’s Eastern Department on Turkish, Persian, Syrian and Arabian affairs. It was during this time, in 1926, that George and Geraldine first met the young Saudi Amir and future King, Faysal bin ‘Abd al-‘Aziz, during his second visit to London. A natural and persuasive committee man of firm opinions, George was adept at seeing the big picture and formulating policy accordingly. His talent for administration and skill at handling committees were recognized in 1930 by his appointment as head of the Department, succeeding Sir Lancelot Oliphant, and it was during his tenure, in 1932 and 1937, that he made his two Middle Eastern journeys. On both of these, he saw to it that Geraldine accompanied him, despite the FO’s traditional opposition to overseas travel.

Britain and the Arab world between the wars

As head of the Eastern Department, Rendel’s remit covered what today we think of as the Middle East – the Arab countries, Turkey and Persia. But chiefly he had to deal with issues arising from the complex pattern of disparate arrangements by which British control was exercised over a large part of the Arab world.

In the wake of the Ottoman Empire’s collapse at the end of the First World War, the responsibility for its Arab provinces fell to Britain, with the exception of Syria and Lebanon, where the vacuum was filled by France – in fulfilment of the terms of the secret Sykes–Picot Agreement of 1916 between the two powers. During the interwar years, Britain’s dominance of the region reached its zenith, its so-called ‘moment in the Middle East’, but its supremacy faced a rising tide of challenges from emerging nationalist aspirations.

British power in the 1920s seemed monolithic, but had in fact grown organically by means of an untidy patchwork ofad hocarrangements, no two of them precisely the same, and by the end of the 1930s the structure was creaking. Egypt, though nominally independent, was still effectively under uneasy British occupation. Palestine was administered by Britain under a League of Nations Mandate, while Transjordan had been created in 1921 as a British protectorate linked to Palestine. Iraq too was initially administered under a League of Nations Mandate, not directly from London but by the Government of India. This arrangement met with stiff opposition from Iraqi nationalists, and was modified by the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty of 1922, which placed the Hashimite Amir, Faysal I, on the throne and conceded a measure of autonomy under British supervision. This was superseded in 1930 by a new Anglo-Iraqi treaty, conferring still greater independence while attempting to maintain British interests.

Within Arabia, Oman and the various small shaykhdoms on the Arab shore of the Gulf were still controlled by the simple protectorate treaties with British India that had evolved during the course of the 19th century. Each was supervised by a Political Agent reporting to the Political Resident based at Bushire on the Persian coast, who in turn reported to Bombay; and two of them, Muscat and Bahrain, were put under even closer supervision by the appointment of permanent Special Advisers to their rulers. Aden and the Aden Protectorate were likewise still being administered from British India, though in 1937 Aden itself would be converted into a Crown Colony administered from London. Such arrangements involving the Government of India reflected conditions in the 19th century, and were rapidly becoming anachronistic, particularly in view of the looming possibility of Indian independence. Nor were the lines of official responsibility for these mandates, protectorates and occupied territories organized into a rational structure, handled as they were by a cumbersome collaboration between the Colonial Office, the Government of India, the India Office in London, the Foreign Office, the War Office and the Admiralty.38Farsighted officials such as Rendel were firmly of the view that they were ripe for reorganization. In 1930, a body was set up specifically to co-ordinate the policy-making of these departments, unmemorably named the Middle East (Official) Sub-Committee of the Committee of Imperial Defence, and George Rendel, by now a key figure, was appointed to serve on it as the Foreign Office representative.

Saudi Arabia in the 1920s and ’30s

The Arab region that we now know as Saudi Arabia was an anomaly, in that it had never quite been drawn into Britain’s web of control. The division of British authority in the Middle East, between London on the one hand and India on the other, reflected the pattern by which its power and influence had been projected from either direction over the previous century and a half. The division actually made a kind of geographical sense, embodied as it was by a formidable natural barrier: the vast landmass of inland Arabia bordered to the north by the Syrian desert – the land that was now in the process of evolving into the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. This arid and sparsely peopled tract was the sole region of the Arab world that historically had eluded domination by European powers.39Najd had suffered invasion and colonization only once, between 1811 and 1840, and that had been at the hands of Ottoman Egypt. Muhammad ‘Ali Pasha’s forces had managed to destroy the capital of the First Saudi State, al-Dir‘iyyah, in 1818–19, but the cost had been crippling and the Egyptians eventually gave up their attempt at occupation. Vague subsequent Ottoman claims of suzerainty over its feuding amirs fell far short of any kind of political control, and Najd had long been regarded by other outsiders as an ungovernable void, of no economic or political interest.

But now, during the First World War and the 1920s, a new force had arisen out of this very space. Its charismatic Amir and now Sultan, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz Ibn Sa‘ud, had united the regions that today form the Kingdom by a series of arduous military campaigns between 1902 and 1926. Most recently, he had progressively subdued his northern rival, Ibn Rashid of Ha’il, in 1920, taken over much of mountainous ‘Asir in the south-west and, in 1925–26, put an end to the centuries-old governance of Makkah and the Hijaz by the Hashimite dynasty. During the War, Britain had given much support to the Hashimite Sharif of Makkah in fomenting the Arab Revolt against Ottoman rule – an episode glamourized by the publicity surrounding the exploits of T.E. Lawrence. It is less well known that the British had, at the same time, been giving financial and material support to Ibn Sa‘ud, mainly to prevent him from attacking the Hijaz and undermining their war effort. This support was delivered from the Indian side through the agency of Sir Percy Cox, Capt. W.H.I. Shakespear and Harry St John Philby. All three men had dealt at first hand with the new potentate in Riyadh and had had ample opportunity to fall under his fabled spell.

After the War, Britain became disenchanted with the increasingly difficult Sharif and, in 1924, terminated its subsidies to both the Hijaz and Najd. This had the effect of leaving Ibn Sa‘ud a free hand. As a result, the real balance of power in the Peninsula was allowed to assert itself, and rapidly did so. By the mid-1920s, Ibn Sa‘ud controlled an enormous area, very nearly coterminous with Saudi Arabia’s borders today, embracing the Hijaz as well as Najd, al-Hasa and ‘Asir. By that time Britain, alive to the process of a new state forming in the region, was already conducting negotiations with the Najdi ruler to establish frontiers with Iraq, Transjordan and Kuwait.40Ibn Sa‘ud was the first Arab ruler to have his sovereign independence recognized when, in May 1927, Britain concluded the Treaty of Jiddah with the Kingdom of the Hijaz and Najd and Its Dependencies.41From this moment on, the Saudi kingdom was to be the sole truly independent Arab state in a region otherwise under British control.

It was not all plain sailing for Ibn Sa‘ud, however. In the late 1920s, his unification project was almost fatally undermined by the Ikhwan Revolt in northern Najd. These extremist Wahhabis, so-called ‘warriors of Islam’, were suppressed with difficulty, and with help from British forces on the frontiers with Iraq, Kuwait and Transjordan.42Nonetheless by 1930 the new country was ready to look outwards, and to take its place on the international stage as a recognized state with a defined territory. In September 1932, its constituent parts were jointly proclaimed The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia – a name suggested by George Rendel himself and agreed in his office in London.43

Formal recognition entailed the appointment of diplomatic representatives by both sides. The British consulate at Jiddah was upgraded to a legation, and Sir Andrew Ryan appointed as first minister, taking up his post in 1930.44One of Rendel’s first tasks was to obtain approval for the appointment of Ibn Sa‘ud’s choice as his man in London, Shaykh Hafiz Wahba.45Shaykh Hafiz would remain in post for the next twenty-six years, making many warm friendships among the British and eventually becoming doyen of the Diplomatic Corps in London. It was through him that the Rendels’ 1937 visit to Saudi Arabia was arranged, and he himself accompanied them all the way from al-‘Uqayr to Jiddah. He gave ready support to many Britons engaging with Saudi Arabia, notably to Lady Evelyn Cobbold when she made her pilgrimage to Makkah in 1933, and to Princess Alice and the Earl of Athlone in 1938.46He and George Rendel became friends and political allies, and the Rendels would maintain friendly contact with his family at least until the 1980s.47

Ibn Sa‘ud’s military and political successes were not matched by economic gain. Oil had not yet been discovered. However hard it may be to imagine now, in the 1930s Saudi Arabia was among the poorest countries on earth. In the early part of the decade the world economy was mired in the Great Depression, and the infant kingdom was still reeling from the Ikhwan Revolt. It had no source of income apart from pilgrimage receipts, and hard times meant that pilgrims from abroad were few: in 1933 numbers slumped to a mere 20,000, an all-time low.48In these desperate straits, Philby records the King declaring wearily: “I tell you, Philby, that if anyone were to offer me a million pounds now, he would be welcome to all the concessions he wants in my country.”49

That was in 1931, and in the spring of 1932 the King despatched his second son, the Amir Faysal, to London again, this time to ask for a loan of half a million pounds, in exchange for which “he would welcome the assistance of British firms in exploiting the mineral resources of his country”. The King was offering an open door; but Sir Lancelot Oliphant, Rendel’s cautious boss in the Foreign Office, warily refused to go through it, citing economic difficulties and lack of business confidence as reasons – thus earning his sobriquet as “the diplomat who said ‘No’ to Saudi oil”.50Curiously, Rendel makes no mention at all in his published memoir of this visit by Faysal to the UK, though he must have been involved in it, and indeed confirms in his 1937 report that he had last met him in London in the summer of 1932. Faysal was accompanied by Sir Andrew Ryan throughout his tour.51

Economic salvation arrived in the nick of time from another direction, in the form of the pro-Arab American philanthropist, Charles R. Crane, who was invited to Jiddah at Philby’s suggestion. This led to negotiations with Standard Oil of California (socal) for the Eastern Province oil concession. In late February 1933, socal’s negotiators Lloyd Hamilton and Karl Twitchell arrived in Jiddah to compete for the concession with the Anglo-Persian Oil Company’s Stephen Longrigg. The stage was set for the historic deal that would eventually transform Saudi Arabia into one of the world’s richest countries.

The emergence of a new political unity, combined with the prospect of oil and the development of motor transport and radio communications, spelled the end of central Arabia’s long isolation. Najd was opening up. Diplomats such as Andrew Ryan, Gerald de Gaury and Reader Bullard, as well as travellers such as Philby and Harold Dickson, would soon be beating a bumpy path by car to its growing capital, Riyadh, which hitherto had been accessible to only a handful of foreigners.52American oil men and other prospectors added to the medical missionaries who had preceded them.53From a British foreign relations perspective, the new kingdom straddled the old divide between London and India. To continue to formulate policy towards Arabia from two different directions was to invite confusion. George Rendel was characteristically clear-sighted about the need for rationalization, and played an important role in bringing relations with Arabia as a whole under London’s purview at the expense of the Government of India, and imposing some coherence on the system.54

During the two interwar decades, Saudi Arabia was coalescing from an unstable assortment of feuding tribes and principalities into a unified state. Its creator – progressively Amir, then Sultan and finally King – had transformed himself from a tribal and sectarian chieftain of uncertain prospects into the ruler of a country on the international stage and, as the new custodian of Makkah and Madinah, a central figure in international Islam. As such, its monarch required more tactful and deferential handling than other Arab leaders, something to which not all officials were quick to adapt, though Rendel recognized it clearly enough. From a British geopolitical perspective, Ibn Sa‘ud’s unification project had created a state that was able to threaten the frontiers of Iraq and Transjordan and the security of Britain’s protectorates along the Gulf coast.55More seriously still, he was regarded by Britain’s 100 million Muslim subjects in India as protector of Islam’s holy places and the pilgrimage. British officials had to get used to treating this potentate, whom they had previously regarded as a remote desert chieftain easily manipulated by small quantities of money and guns, as a serious political force in the region to whom they would have to make concessions when necessary. Britons on the ground who already knew Ibn Sa‘ud (such as Gilbert Clayton, Gerald de Gaury, Andrew Ryan, Reader Bullard and Harold Dickson) were not at all taken by surprise at his ability to expand into his new roles and status. In London, George Rendel was foremost among those recognizing this evolving state of affairs and, as a man of forthright views, was influential in bending his superiors in the Foreign Office to his way of thinking.56So far from being symptomatic of the general failure of British imperial nerve in the 1930s, this particular recognition was a natural and inevitable adjustment to a new reality – one which would acquire even greater solidity with the discovery of oil in commercial quantities in Saudi Arabia in 1938.57

First Middle Eastern journey, 1932

It was in connection with Iraq in 1932 that George and Geraldine Rendel made the first of their two Middle Eastern journeys.58