7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Grosvenor House Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Ahimsa: In Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism, respect for all living things and avoidance of violence towards others. On a 32,000 km journey through six Asian countries over six months, Caroline, a journalist, and her husband David, a retired paramedic, become increasingly aware of animal welfare, poverty and what we are doing to the planet. They had no idea when they set off that they were going to end up vegan. Ahimsa is the story of their journey, meeting colourful characters and exploring many philosophical themes along the way. It is topical and questioning, in parts funny, sad and increasingly angry.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 399

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

For Aurora, my little herbivore.Aurora was the mythical Roman goddess of the dawn. Let us hope we are at the dawn of a new, more compassionate world. You might be small, but you will come to see how big your actions can be and what difference you can make in your lifetime.

Foreword

1 Medication for the soul

2 Well, if the kids won’t leave home…

3 Ladyboys, lizards and locusts

4 Elephants we’ll never forget

5 Oh ye of little faith

6 What’s the worst that can happen?

7 And then he kissed us

8 It’s not very autism-friendly, is it?

9 Tears at the killing tree

10 The scars on Sri Lanka

11 Turns out I’m a bit of an eco-warrior

12 Rice between your cheeks

13 Be the change that you wish to see in the world

14 Granny-ji farted in the back of the bus

15 I moo’ed at a mullah

16 Do you know how lucky you are?

17 Sawubona — ‘I see you’

18 Diwali in the desert

19 Big ambition of a small slum girl

20 Never give up

21 It’s enough to make you sick

22 Temples, toilets and tampons

23 Crazy old Delhi

24 The greatest peaceful revolution ever known

Tips for new vegans

Book club questions

Notes

Acknowledgements

About the author

Copyright

Who knows where any journey undertaken with an open mind and an open heart is going to take you?

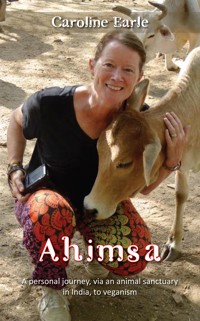

When grandmother Caroline Earle embarked on a gap year to mark her semi-retirement in 2018, she fully expected that the months of travel would leave her with a rich store of memories but she cannot have known how profoundly the experience was to change her whole personal outlook, her principles and her way of life.

This inspiring memoir is built around a central story of one woman’s conversion to veganism. Not so long ago, that word would have demanded an asterisk and an appended definition explaining the nature of a mysterious eccentricity indulged in by a tiny minority. Today, veganism is rapidly becoming a mainstream choice… but this is not a fashionable lifestyle guide, let alone another cookery book. Instead, it is an uplifting, thought-provoking account of the gentle philosophy that lies behind the trend and the way in which it revealed itself to a hard-headed and sophisticated professional, not least through the simple act of cuddling a cow in India.

In eastern religions, the concept of Ahimsa from which this book takes its title encompasses compassion, non-violence and a desire to do no harm to other living creatures. At a personal level, as in this case, it can signify a commitment to kinder, more mindful living in all respects and, when it comes to food, to the adoption of a plant-based regime including no animal products of any kind.

As dramatic as it has been, Caroline’s life-changing epiphany did not quite come out of the clear blue sky of Udaipur. It was, rather, the challenging culmination of a complex web of influences, experiences and wisdom gained over many years as a senior journalist in print and broadcasting and a mother with a sometimes troubled family to nurture and protect. Ahimsa came at the right time and in the right place to make sense of it all.

Readers will meet her family, including Zippy, a rescue dog with his own message to convey about the meaning of life, and David, the retired paramedic husband whose pugnacious sense of justice helped point towards a new spiritual direction as they travelled together through South-East Asia, Sri Lanka and India.

The story of their midlife journey is by turns entertaining, moving, sad and ultimately happy, but this is no airy New Age account of yet another western traveller going east to find herself. Anyone who has known Caroline in her various roles as a journalist and charity fundraiser in her native Jersey is likely to testify to her no-nonsense approach to practical matters, her sometimes slightly scary efficiency and her formidable strength of character.

For that reason, the knowledge that close encounters at an animal sanctuary in a strange land could have such an enduring impact on her life makes this book’s vegan message all the more powerful, while those still searching for a personal philosophy of any kind that feels right and recalibrates their world can celebrate the news that there is no age limit on adventure or the chance of a life-changing experience.

Caroline still lives and works in the Channel Islands, a much-blessed and beautiful archipelago just off the coast of France. One of its most renowned residents, Victor Hugo, once observed that there is nothing more powerful than an idea whose time has come.

As the 21st century unfolds, many more will find themselves discovering that veganism is just such an idea.

Chris Bright

Former Editor, Jersey Evening Post

Once upon a time, there was a wise man who used to go to the ocean to do his writing. He had a habit of walking on the beach before he began his work.

One day, as he was walking along the shore, he looked down the beach and saw a human figure moving like a dancer. He smiled to himself at the thought of someone who would dance to the day, and so he walked faster to catch up.

As he got closer, he noticed that the figure was that of a young man, and that what he was doing was not dancing at all. The young man was reaching down to the shore, picking up small objects, and throwing them into the ocean.

He came closer still and called out: ‘Good morning. May I ask what it is that you are doing?’

The young man paused, looked up, and replied: ‘Throwing starfish into the ocean.’

‘I must ask, then, why are you throwing starfish into the ocean?’ asked the somewhat startled wise man.

To this, the young man replied: ‘The sun is up and the tide is going out. If I don’t throw them in, they’ll die.’

Upon hearing this, the wise man commented: ‘But, young man, do you not realise that there are miles and miles of beach and there are starfish all along every mile? You can’t possibly make a difference.’

At this, the young man bent down, picked up yet another starfish, and threw it into the ocean. As it met the water, he said: ‘It made a difference for that one.’

— Loren Eiseley, philosopher and anthropologist (1907-77)

Medication for the soul

‘Animals are my friends and I don’t eat my friends’

—George Bernard Shaw

It was the story of the staggering street dog with maggots in his head that has brought us to Udaipur.

A few weeks back we saw a two-minute video on Facebook showing how the rescue team at Animal Aid Unlimited saved a dog’s life in the nick of time. We didn’t hesitate to add the animal sanctuary to our flexible schedule.

Primarily we are here for the dogs, but we are surprised by how much we are touched, literally and spiritually, by all of the other animals.

One of the first things that most volunteers experience is bottle-feeding the calves. My first one is pure white, with the softest hair you can imagine. She nudges in to me, gulps down her milk and comes back for more. Afterwards, she stays for a cuddle, her milky breath in my face.

On any typical day one of our tasks — indicated by the hand-drawn red heart on the whiteboard — is to ‘give love’ to the sheep and brush them. Some allow this, but there are two young brown ones who are not so sure. To be honest, sheep have never done much for me, probably because I have never got to know one. Usually they are skittish and run away, and their coat is hard and wiry so they are not actually that nice to touch.

But here is my first lesson. While I am sitting amongst the calves one morning, a sheep comes over to say hello. (We are always saying hello to the animals.) It is always nice when an animal comes to you for attention, rather than the other way around.

I duly say hello. She looks me in the eyes. There is a moment when you seem to communicate with an animal, when you acknowledge something special, and you just stay with it for as long as you can. You know it isn’t really personal, but you like to think it is.

When you look into a pair of huge brown eyes, you can’t help but wonder what goes on in the animal’s mind. It reminds us that animals are sentient beings, capable of feeling. It seems obvious but, as with many simple truths, we sometimes need reminding.

The sheep stays there for a chat and a rubdown. And I love it. I am surprised by how gentle a creature she is.

I never cease to be amazed by how many animals are open to trusting a human being again, despite what has happened to them… the donkey who has been beaten about the face (a court case is pending), the cow who has had acid thrown on her, the dog who has been tied up with wire around her jaw for so long that she is permanently scarred.

And then you get another lesson when you find the courage to sit next to a huge water buffalo or brush the flank of a super-sized bull. In the cow and donkey sanctuary in the early afternoon heat, we get to brush the animals. I don’t think most of them really need brushing, but it is a good way to bring us closer to them — and they seem to like it.

When a young, but still impressively large, water buffalo comes to you, it is very special indeed. Their skin is tough and the hair on the back of their wrinkly necks is long but thin. They like being brushed, much like I imagine they like having a bird on their back to pick off the bugs.

The one I am drawn to has a small tuft of white hair on her head and she is called Flower.

There is a large bull who is interested in being brushed. At first, when he walks over, I shy away, especially as he tends to shift others out of his way with his horns. Soon I realise that he is just jealous, so I pluck up the courage to brush him and he stays there contentedly until he has had enough and ambles off.

The sanctuary area for cows and donkeys is a peaceful place, with plenty of room for the animals to relax. When they are standing still or lying down, you don’t see their disability. It is only when they move that you notice the amount of limping and hobbling, or where limbs are missing. Most donkeys have one if not both front ankles bandaged from where they have been tied up for too long. They are, however, very capable of leaning on those two front feet if they need to give a swift kick from the back, to any animal that mildly irritates them.

There is another enclosure where cattle and donkeys are recovering, which includes the ‘accident and emergency’ area. One cow has a lot of bandaging around her head. We see the staff changing the dressing. As a veteran paramedic, David’s instinct is to get a closer look. Over 25 years he has seen things which are best described as surreal. The large hole where the eye socket should be is astonishing but the animal doesn’t seem to be in any pain while the staff irrigate it with saline. We understand that maggots have already eaten the nerve endings.

This, David says, really is surreal.

In this part of the sanctuary we can sit with a dying cow. In India, cows are sacred and it is against the law for one to be put down. All that staff can do is ease their suffering with medication. One black cow is brought in with a broken back from which she can never recover. She is lying in the shade on a black plastic mat, where she is kept as comfortable as possible. It is only a matter of time.

And, if volunteers have the time, they can sit with her. David sits with her for quite a while, stroking her strangely cold head, talking gently, reassuring her and batting flies away. It is a humbling and moving experience. It seems deliberate on the part of a large black and white horned bull that he sits himself right next to her. At one point he licks her face. We don’t think they have been brought in together, but I hope she feels comforted by his presence. She is not there the next morning.

It’s in the hours before death that you can only hope that the magnificent creature in front of you knows that it is not alone. It is cared about, it is loved. This perhaps is the purest definition of the word ‘namaste’. I see the beauty of your soul.

Cow 17 is my favourite. She is young. I have no idea about her history, but she is ridiculously friendly. To while away half an hour with her, lying in the straw, with her head nuzzled in to your chest, is heaven on earth. Her face next to mine, she smells like she has eaten candy floss. Her big brown eyes, just gorgeous.

I promise her I will never eat animals again.

I even learn some cow physio. Volunteers like me require no animal or medical background to do this, just a shed-load of common sense, love and compassion. And time. Time seems to stand still when your entire focus is a cow which is recovering from injury, usually the result of a traffic accident. The daily routine involves checking the whiteboard for which animals need attention, and making sure you are rubbing their muscles to get the blood circulating, or just giving them a lovely massage around their shoulders.

Towards the end of our stay, I do some physio on Cow 109. We are already acquainted as I have massaged her a few times before. She has a broken back leg and some bandaging under her front. She is sitting in the shed and I rub her back and her shoulder, thinking of nothing much. But when I stand up to move to the next animal on the list, the vets come over to lie her down on the floor and swiftly administer a drug. I am not sure what is going on. She seemed fine. My physio shift is ending and I have to go to dog-sit in a different area. I deal with a couple of bouncy dogs, one of whom treads in his poo and transfers it to my neck. (Many a time we share a tuk-tuk back to our homestay and, apologising to the driver, laugh that we are wearing our favourite perfume, Kennel No 5.)

When I return to the cow area that same afternoon, the big black cow has died. I pat all the cows who are down, the grey one is cold, the brown one definitely won’t last the night. But oh my God, no, please not 109 — she is too young to die. She was ok. I keep willing her to get up. I ask a vet what has happened. He says she isn’t getting up on her feet. I know this is bad news. Barely holding back tears, I go to the calves’ enclosure to calm myself down. My favourite calf ambles over as if to reassure me.

Before I finish for the day, I check on the cows once more. 109 has died. I get in the tuk-tuk, put my sunglasses on and cry my heart out all the way home.

Despite having emotional moments with cows, sheep, goats, water buffalo and even a donkey, my favourite times are with the dogs. You can quickly establish a rapport with a dog and I find myself returning to the same disabled dogs in Handicapped Heaven. There are dogs who have lost limbs, most of them have lost the use of their back legs and they are either dragging them behind them or the limbs have been amputated. There is one, Deepak, who has only one and a half legs. He gets about all right. He is a handsome dog, with quite thick rusty brown fur.

Then there are the ‘ugly dogs’. It’s what they are called for identification purposes but everyone knows that they have even more beautiful souls. They are really friendly, but you can see why they have been rejected. They might have a long tooth protruding forwards, or a misfitting jaw, or no lower jaw at all, leaving the tongue to flop out and get covered in sand when they are lying down.

In a corner I sit with one dog who responds immediately to being touched. Her haunch starts moving like she is scratching her ear, though there is no leg there. I scratch her ear for her. The haunch keeps moving.

Another dog, with longer fur, just rolls over in the sand, inviting a tummy rub. He is so chilled that I find myself playing with him like I would a normal dog, a bit more forcefully and a bit more fun, and it is only later that I realise his back legs are not functioning.

We have been shown how to give the dogs a lovely soothing back massage and how to rub their shoulders — it’s where most of them will carry their tension from having to lift their bodies and compensate for their disabilities.

One pretty black dog is called Michael Jackson. He has the most lovely nature but thanks to a neurological deficit his legs are very wobbly. He moves like he is a stringed puppet who has just consumed seven pints of beer. He often falls over as his brain misjudges the distance between his paws and the ground. And when he tries to run, it is cartoon-like in the way his back legs try to get him moving. He never seems to need reassurance but I often give it.

Later in the week we are introduced to the area where it is not known for sure what, if any, diseases the dogs are carrying. We have had our rabies injections so we are allowed in, but we are advised to exercise more caution. Somehow the reward here is even greater. Sitting for ten minutes with a dog who is in a small kennel for his own protection while he heals feels like valuable work. You can make a real difference to their day. Some are so mangy they have not a scrap of fur. One bitch has skin so hard, dry and cracked that she looks like she is half-armadillo. Some wag their tail and you know you can relax with them. Others don’t have a tail that can wag any more.

Some dogs press themselves against the back wall of the kennel, keeping as far away as possible, eyeing us suspiciously as we talk to them and tell them how handsome and brave they are. Gradually their natural curiosity overrides their fear and they edge closer until they sniff an outstretched hand. Patience is richly rewarded when a scruffy mutt allows us to stroke his neck or tickle behind his ear.

Some have ‘lampshades’ on their heads, the plastic cone to stop them from licking a wound. One white dog is so nervous of me that I cannot touch him. But he is ok with me just sitting, chatting. It seems perfectly natural to be telling him about my rescue dog back home. I change his matting, top up his water and leave him just a bit better than he was ten minutes before.

An important part of Animal Aid’s work is education, teaching people about animal welfare, taking their message into schools and inspiring local communities to protect the lives of all animals. The staff, who also run a programme of spaying, neutering and anti-rabies inoculation, respond to calls to help more than 50 animals every single day.

One of the first things they taught me was in their volunteer manual, where the founders explain how the animals have opened their eyes to what happens in any business that uses animals as commodities — like dairies and poultry farms, the leather industry, and slaughterhouses and laboratories where animals are used in experimentation.

‘We love knowing that every volunteer will have a chance to become closer to all animals, and maybe come to new realisations about the privilege of protecting them, including no longer eating them or using them for their products,’ the manual reads.

Each day we go back to our homestay sweaty, dirty, sandy, smelling of dogs, with pee and sometimes poo on our clothes, mixed in with dried milk splatters from the calf-feeding, a big smile on our faces and our hearts bursting with love. We are in a place of healing, though we suspect that humans are getting as much healing as the animals, if not more. Over our lunchtime thali, one volunteer describes it as medication for the soul.

Personally, I have never been more ‘in the moment’ than right here in Udaipur.

Well, if the kids won’t leave home...

‘The more that you read,

The more things you will know.

The more that you learn,

The more places you’ll go!’

— Dr Seuss

‘I can never have enough of India. I long to return.’ These are the words of the same woman who welled up at her first sight of the Taj Mahal, saying: ‘There are no words… for that.’ Actress Miriam Margolyes was one of the stars of the TV series The Real Marigold Hotel, where ageing celebrities are sent off to India to see how they might cope with retirement there.

We fell in love with the idea of spending at least three months in the country, but it wasn’t until the second series that we hatched a plan. Jealousy grew as we watched the likes of Lionel Blair and Dennis Taylor living for weeks in Kerala. An idea began, a plan started growing, a dream really was going to become reality. We could talk of nothing else.

Already big fans of the original film, The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel, we longed to go to Udaipur, where some of the movie had been filmed. It really did feel like a ‘now or never’ chance while adult children were settled, grandparenting duties were not yet onerous, and we had saved enough money to quit our jobs.

It wasn’t long before we realised that perhaps it was not the best time to visit as we were highly likely to clash with monsoon season. Wet season itself would be ok but, at our age, we felt we should err on the side of caution, especially after watching news coverage of India’s worst monsoon in years later in the year. It killed more than 1,000 people and brought down buildings in major cities.

We both admit that there is a part of both me as a journalist and David as a keen amateur photographer (more than the paramedic instincts) which wanted to be there at the time, ready to document as well as help in time of need. Not for the last time were we thinking: ‘Maybe if we were 30 years younger.’

Seeing as we were already counting down to the last day at work, we felt we couldn’t just shift our plan further into the future and instead we decided to add to the front of the itinerary by visiting other countries before we reached India. Three months became six. We would fly to Bangkok on 1 July 2018 and return just in time for Christmas.

The planning was part of the fun. A full year before departure day, a large map of India found a permanent place in our summer room. That’s the posh term for our extension. What we liked to think of as our cosy winter lounge had been taken over as a bedroom for a son who had returned home. One elderly friend regularly lets us know that he thinks we live in a bus station, such are the comings and goings of people in our house.

We added sticky dots to the map to indicate where we wanted to visit, usually in response to something we saw on TV, and we set up our blog, kidswontleavehome.blog.

As part of the preparation for six months in developing countries, David had to research the availability of treatment facilities for his blood-clotting deficiency. At home we take so much for granted, including the fact that Factor 8 treatment for haemophiliacs is readily available. When getting his routine inoculations, he joked with his GP about the availability of such life-saving treatment in places like Vietnam and Cambodia. He asked further about what might happen if he had a significant bleed from being in a car accident, for example, and they laughed that in that sort of scenario essentially it would be game over.

It only served to reinforce his philosophy: You only live once? No, you live each and every day. You die only once, usually not before your allotted time. ‘I would rather die with my beloved, doing what I love, than stay at home,’ he said. (He assures me that he means me and not his Canon 70D.)

Much as we get on well with each other, we decided that we needed to come up with a safe word in case we were winding each other up while we were on the road. We anticipated that there might be times when we were getting on each other’s nerves and we needed a code which we could use to indicate that we just wanted our own time, David might want extra time processing his photos, or I might want to wander off to the nearest market by myself. Actually, the safe word was two words. ‘Fuck’ and ‘off’.

Visas, vaccinations and kit lists had to be ticked off, but what I hadn’t had to do when I had travelled to Kathmandu as a teenager more than 30 years ago was make sure the household bills were paid, notify authorities that we would be away, teach the kids where the fuse box was, and make sure Zippy had extra dog-sitters and walkers on his rota.

But we didn’t want to over-plan. When we arrived in Bangkok, only one hotel, one train and a one-week stay at the Elephant Nature Park in Chiang Mai were booked. The whole point was to get us out of our comfort zone and David reminded me that the actual travelling between places was very much part of the journey.

Indeed it was. The overnight sleeper trains, the fun to be had in Indian trains (the cheaper the seats, the more interesting the ride), the horrendous 24-hour sleeper bus to Hanoi, the six-hour minibus ride to Phnom Penh with me vomiting most of the way, the slow boat down the Mekong in the pouring rain, the terrifying car drives down mountains in the north of India… They all made the best stories in the end. A flexible and independent itinerary meant that we could add in towns that we heard about from fellow foreigners along the way, places like Jaisalmer, Pushkar and Shimla. Talking to other travellers (as well as locals, of course) was always a joy, whatever their age or nationality.

Mostly, it made us feel young again. We enjoyed the kudos we gained in an instant from younger travellers when we said we were on the road for six months. We couldn’t, however, totally align ourselves with backpackers. Because we were approaching our mid-50s, we decided that our backs were not quite up to the challenge. David’s camera bag alone weighed 18 kg. Our heads had to rule our hearts and we opted for a medium-size wheeled suitcase each.

Our first aid kit was huge. David knew what the serious stuff should be. His box of tricks included syringes, cannula, scissors, tweezers, scalpel and suture kit which led him to observe that if our budget ever ran out he could probably extract one of my kidneys to sell on the black market. Luckily our financial projections were accurate enough, even if the medical kit was over the top. We used little more than one plaster.

Having visited India as a cash-poor student at the age of 19, I felt I knew that there were only three essentials that I had to pack: diarrhoea-stoppers (a friend kindly gave me a cork as a leaving present), rehydration salts and mosquito repellent. As it turned out, all these would be available along the way. It should be added, however, as every traveller surely discovers, no mosquito repellent actually works. They are the one creature on earth that, as a new vegan, I still have no trouble killing. It’s not like mosquitoes are ever going to be endangered and quite honestly it could be a good thing if they were.

When we boarded BA009 to Suvarnabhumi International Airport in Bangkok, I was looking forward to a number of things, the main one being not working. Having worked full-time since 1986, as a journalist in radio and print, I can safely say I felt a little burnt out. We were looking forward to the adventure, the different cultures, religions, spirituality, the people we would meet, the World Heritage sites, the food, the music. We wanted to push our boundaries, feel alive, spontaneous and excited. We wanted to do things that we could bore our grandchildren with for many years to come.

We are not really the kind of people who do beaches or museums but there was a place for them too alongside the diverse mix of countryside, cities, slums, historical sites, ancient temples, volunteering with rescue dogs, stunning beauty and wretched poverty, heat, dust and rubbish. We relished the idea of living out of a suitcase and eating simple food. Many a time we were more than satisfied with fried rice or noodles and a cold beer.

For David, it was all about photography. He armed himself with five cameras, four lenses, lens hoods, chargers, battery packs and remote triggers. In fact, as he casually mentioned as we waited in line for the first airport security check, everything one could possibly need to make a bomb. The quantity of camera gear was something I continued to question long after we had landed in Asia. I was still not sure he had worked out the right storage and cataloguing system for the 25,000 images he was going to take. (To this day, I am not convinced he has it figured out.)

On the day of our departure, he wrote in his journal: ‘This journey will, I hope, be a physical, mental and spiritual cleansing. A mid-life re-boot. A time for reflection, taking stock and contemplation of what remains of our all-too-short time on Earth. I hope one day to be an old man in relatively good health, poring over thousands of photos but, as I have witnessed in my job, tomorrow is promised to no one and each day is precious. Hug your dog every day. Tell him he is the best and that you love him totally. Ditto your wife.’

(The dog always comes first.)

Before we left, we knew there were some things that we would not look forward to, and they mainly featured bodily functions. We reckoned that a dose of Delhi belly was inevitable and likely to hit way before Delhi and we hoped that our bladders would hold out on long journeys on public transport.

And the flight home. We were definitely not looking forward to the flight home.

Normally I scroll past YouTube videos on animal rights but for some reason, in the spring before we left home, I clicked on The Food Matrix — 101 Reasons to go Vegan. The speaker was saying that in the United States 300 farm animals die every second.

Every second.

So in the time it takes you to read this sentence, that’s about another 1,500 animals slaughtered. And that’s just in the US.

I started researching it. I started clicking on more links. No wonder some people call it the animal holocaust. Some people question the use of the word holocaust in this context, but if you take the definition ‘destruction or slaughter on a mass scale’, which it is, then I don’t see the argument. I have no wish to offend Jews or detract from the Holocaust with a capital H.

And it wasn’t just the killing of sentient beings that was starting to bother me. It was the unimaginable suffering that comes with intensive factory-farming.

It was quite literally a penny-dropping moment and it was enough to make me vegetarian straight away. But not vegan, as I was keen to tell my sister Nicola, who has been vegan for more than 25 years. ‘I could never be vegan.’

She merely replied: ‘Never say never.’

When I mentioned to David that I thought I had had an epiphany, he asked me how many Wet Wipes I was going to need. No, not that, I said. You do realise what we are going to have to do, don’t you?

Now, thus far in our lives, we had not been your average tree-hugging, organic, save-the-planet kind of people. We were hard-working parents who had finally, in our 50s, found ourselves with a bit of time on our hands. But when we watched the documentary Dominion as we neared the end of three months in India, we realised we were at a turning point in our lives.

Donald Watson, who founded the Vegan Society in 1944, said that veganism ‘starts with vegetarianism and carries it through to its logical conclusion’.

I didn’t understand that until 2018. It could be said that I am a fan of the long, slow build-up and certainly our route to vegetarianism had taken its time. We had thought about it before, dabbled a bit, thought we could do it, but we were never really committed. Nothing had given us proper impetus. Not even Nicola’s arguments and vegan posts on Facebook. It was only when David suggested being vegetarian, towards the end of 2017, that we decided that we were going to do it. We were doing it for two reasons, partly for our own health. We thought it would be a good idea at our age to cut out red meat, as well as bacon and processed meats. The other reason was that our travels would be taking us to Asia, not exactly known for its animal welfare and quality food production.

David didn’t fancy eating meat that turned out to be, say, goat. Personally, that didn’t bother me. I didn’t want to eat badly kept meat, which could be a potential health hazard. In Kathmandu, a few years back, we had seen slabs of raw chicken out in the sun, unrefrigerated and covered in a layer of dust kicked up by a bus.

The first few weeks of 2018 was easy enough. We didn’t want to tell my sister until it stuck. I told her two months later.

What neither of us had anticipated was that our incredible adventure would be life-changing. David and I had managed to take a step back from stressful careers and the pressures of normal family life. Our minds cleared. At last we had the time and emotional energy to read and reflect. It was a journey which time and time again highlighted our concern for people who live in abject poverty, the environment and, above all, animal welfare. This journey would cause us to re-evaluate our place in the world and our relationship with other species.

Ten or 20 years ago, mention of the word vegan might have conjured up an image of a strict, perhaps restricted, diet and militant tree huggers who were a waiter’s nightmare but, as we were to discover, veganism is more a way of living that seeks to do the least harm to other living creatures. This, of course, precludes eating animals and fish, but also requires a greater awareness of what happens in the dairy and egg industries, as well as what is in the household products we use, cosmetics, medication and even clothes.

For some, the decision to avoid meat is made on health grounds, for others it is in recognition of the harm that intensive farming inflicts on the environment. For us, it was more about not eating the creatures we claim to love and care about.

Over the coming months, we would talk, discuss and question. It seemed that at every meal-time, we would come up with more questions than answers, more grey areas, more what-ifs. We are reasonable people. What did we think of flexitarians? Was meat reduction enough? Meat only at weekends? Meat-free Mondays? A great start… or akin to saying: ‘I beat my wife but only on a Friday’? What would happen to cows if they were no longer used for milking? If farmed animals are no longer forced to procreate, what will naturally happen to them as a species? What would happen if male chicks weren’t killed?

As we made our way through India from Madurai in the south to Amritsar in the north, I was surprised by the anger and passion that was firing up inside me. There was no doubt about what we were going to have to do. We were going to have to be vegan.

Ladyboys, lizards and locusts

‘The soul is the same in all living creatures, although the body of each is different’

—Hippocrates (460-370 BC)

Since when were choices about what you do on holiday so important? Since the days of social media, that’s when. In the past, maybe we would have gone to see a night-time ladyboy show just for fun and maybe we would have visited the long-necked women of the Karen tribe up in the hills. But within our first week in Thailand we found ourselves making judgment calls as to what was an ethical choice and what was responsible tourism.

It’s not that we are not open-minded. Perhaps we are too open-minded and are always up for hearing a contrary view. Maybe open-minded is not the right word. I don’t want you thinking that we are not up for a bit of fun. David is the most politically incorrect person I know, as well as being someone who loathes injustice, is fascinated by the human condition and is generous to a fault. As is often the case with people who work in the emergency services, he has a dark and, some might say, sometimes inappropriate sense of humour. He also hates bartering, something that does not necessarily stand him in good stead when it comes to Asia.

I, however, like a bargain and I am not afraid of negotiating a discount off anyone, even if it amounts to 20 pence. Radio interview training with the BBC more than 30 years ago taught me not to have an opinion (I imagine it is quite different now) so I can see both sides on pretty much any subject, which means that I can appear indecisive, which drives David mad. When I do know my own mind on a big issue, however, it does tend to mean that I am on it 110%. As you will see.

So, David and I like a laugh as much as the next person and it surprised us when, so early in our journey, we stopped in our tracks to consider our options. Do we go to a ladyboy show? Is it just a bit of harmless fun for tourists which helps people earn some money for themselves and their families? Or is it tacky, voyeuristic and just another form of exploitation? Does this questioning come with age and experience or social media and social awareness? Do we fear that if we post on Facebook that we went to a ladyboy show, our own friends and acquaintances will judge us somehow?

In reality, deciding factors were the distance from our accommodation in the older part of town, poor reviews online, the cost, and the fact that Lonely Planet, which was always by my side, suggested that to enjoy the nightlife properly, we shouldn’t even think about arriving before 11 pm. That’s late, we thought. On this one, the practical had outweighed the ethical. And we had decided already that we were going to have to pace ourselves for six months on the road.

Bangkok, the City of Angels, got us off to an incredible start to our adventure. We were indeed going to have to pace ourselves. Not only was it over 30 degrees every day, but also we had to keep to a reasonable budget. That said, we packed in the magnificent Grand Palace and Wat Phra Kaew, Wat Pho and the Reclining Buddha, a tuk-tuk tour at night, the Golden Mount and the inevitable experience of a Thai massage.

I hadn’t expected to have to encourage David to do this. I fancied a foot massage, not least because it was so cheap. David opted for a rubdown of his neck and shoulders with a woman who had all the physical charm of a bulldog chewing a wasp and the strength of a sumo wrestler. We were shown to a room where other people were coming in off the street, children, adults, locals, foreigners. David at least got a small booth with curtains around him.

As the woman was seeing only to my feet, I was on one of the many reclining chairs lined up in public. I don’t really relax when on full view like that, so it all felt a bit perfunctory. Something to tick off, to say we had had a Thai massage. When in Bangkok and all that.

It wasn’t just sightseeing, of course. We had time to wander at our leisure. We enjoyed walking down backpacker street Khao San Road. Twice. The first time, we made the schoolboy error of visiting early in the afternoon, which turned out to be pretty pointless. The time to go was after dark. That’s when the place came alive with shops and restaurants, and pubs selling laughing gas and buckets of beer. Here, we had our first sight of takeaway grilled spiders, millipedes and locusts. Would we buy a scorpion on a stick? No, we would not. This was part of the show for the foreign tourist, something for drunken lads on their first trip away from home.

We had read that Rambuttri, which runs behind Khao San Road, had better restaurants, and it did. It was well set up for tourists, but already we were thinking that we were not really tourists. Even though, in all practicality, we were, of course.

We knew that Khao San Road wasn’t a true reflection of local life. We were more fascinated by the incredible maze of streets and alleyways of Chinatown, where a map would be useless and where not even tuk-tuks could go. Alleyways got smaller and smaller and there was no end to the number of traders and their tiny shops, stacked to the gunwales with dusty goods, garish plastic toys, thin colourful clothing, jewellery, flip-flops, household goods, all of it cheap and plentiful. How on earth do they all make a living? It was a question I would ask myself pretty much every day for the next six months.

I also wondered what the local traders thought of us, in our funny western clothes, with our white skin, our wealth (even if you are a poor student on a hostelling budget), and how they felt as we looked in on them. Do they wonder why we want to take photos of their everyday life?

Once you have read the book Sapiens: A Brief History of Mankind by Yuval Noah Harari, as we had been doing, you start to question everything you do. Or at least that’s what it made us do. And maybe now was the perfect time to be questioning everything.

It was inevitable that sooner or later we would see something distressing. The first such thing was the old white man who had clearly forgotten to catch his flight home 40 years ago and was wearing short shorts, the likes of which you see on 16-year-old girls in Brighton or Benidorm. I suppose we should have counted ourselves lucky that all we could see was his bum cheeks. And not his ancient, pendulous knacker-tackle looking something like the last turkey in the butcher’s window, as David put it.

Away from the main tourist streets, we would see cats and dogs in cages, not as many as I thought I might, but enough to make me angry. A young dog stared at us helplessly from behind the bars of a cage. Another looked forlorn attached to a short heavy chain. It was heartbreaking.

Bangkok has a large population of street dogs, or soi dogs as they are known. According to the Soi Dog Foundation (www.soidog.org), there are about 640,000 street dogs in the Bangkok city area. The foundation, which was set up in 2003, is doing great work neutering and vaccinating hundreds of thousands of animals, cats as well as dogs. It aims to provide a humane and sustainable solution to managing the stray population for the health and safety of both humans and dogs.

It also campaigns for better animal welfare across Asia and that includes fighting the dog meat trade. Soi Dog reports that the dog meat trade in Thailand is effectively over but it continues to check for any signs of it coming back and it is now concentrating its efforts on neighbouring countries, particularly places like Vietnam where the trade is alive and well. Or perhaps dead and sick.

On its website, the foundation explains why the dog meat trade must stop: ‘The conditions under which dogs are farmed, transported and slaughtered are inhumane and barbaric. The dogs are not humanely killed, many are tortured for hours before being skinned alive. The reason for this is that people believe that the pain inflicted leads to the tenderising of the meat. Most shocking of all is that some dogs are still alive when their fur is removed.’

Although I have been aware that the dog meat trade exists, I had never looked for more information about it, feeling that it was too distressing to think about. But now I firmly believe that we should not pretend it doesn’t happen or just cross our fingers that it will go away.

We saw plenty of street cats too and I feared that they had been subjected to some abuse as they had deformed stumpy tails or no tail at all. I was relieved to find out that there is a genetic explanation for this and it is just the way they are.

Thanks to Google, we also looked up all sorts of details about monitor lizards, which we saw from a long-tailed boat ride on the canals. The second largest lizard after the Komodo dragon, an adult monitor can be more than 3 m long and weigh up to 25 kg. These giant, prehistoric-looking lizards lumber along on land with an arrogant swagger, but in the water where they are very much at home, they swim with an elegant grace. The locals don’t bother them because they pose no danger to humans and they are seen by many as a sign of good luck and prosperity. The fact that they eat rats, snakes and cockroaches adds to their appeal.