Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

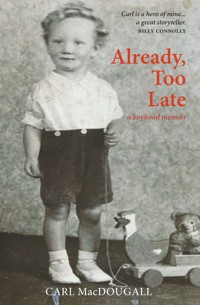

In post-war Glasgow a primary school class was set a composition topic: a memorable family event. Each child completed the assignment – all, that is, but one. Why didn't you write about your family? Please, miss. I didn't, I didn't know what to write. But now, he does. In Already, Too Late, Carl MacDougall, one of Scotland's most accomplished and celebrated literary writers, presents a memoir of extraordinary authenticity and honesty. This memoir takes us through MacDougall's upbringing, both in and out of care on the west coast of Scotland, Fife, and industrial Glasgow, during the first decade of his life. Within this world, now teetering on the brink of our collective memory, sits a single-parent household of German descent; money is tight, trauma roams free and tragedy comes calling again and again. Through a powerful mosaic of stories, MacDougall strips away all rose-tinted sentimentality to create a vivid account of heart-break, dissociation and loss. Already, Too Late is the early life of an outsider looking in, a changeling child, displaced, alone, and – in his own grandmother's words – 'no right'. Because for some, even the very beginning is already too late.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 512

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CARL MacDOUGALL was one of Scotland’s most accomplished and celebrated literary writers. His work includes three prize-winning novels, four pamphlets, four collections of short stories and two works of non-fiction. He edited four anthologies, including the bestselling The Devil and the Giro (Canongate, 1989). He held many posts as writer-in-residence both in Scotland and England, and presented two major television series for the BBC, Writing Scotland and Scots: The Language of the People. With Ron Clark, he co-wrote ‘Cod Liver Oil and the Orange Juice’ – a parody of the song ‘Virgin Mary Had a Little Baby’ – which was adapted and popularised by Hamish Imlach, and more recently by The Mary Wallopers.

He began his life in rural Fife, living with his mother and grandparents in a small railwayman’s cottage. His father away at war, young Carl had the freedom to roam, exploring nature, observing the world with curiosity and innocence. It was an idyllic but isolated existence. After the war’s end, Carl’s father returned, beginning the process of slowly building a relationship with his son. One evening he failed to return home from work on the railway. Carl was never explicitly told what happened. His mother inconsolable, he carefully pieced together the misfortune that had occurred.

The family was forced to migrate to Springburn in the industrial north of Glasgow, echoing the migration that Carl’s Gaelic-speaking father had undertaken in his own youth. The single-parent family was poor, the privations of post-war Glasgow brutal. Tragedy visited again and again. Despite showing significant promise, young Carl was failing at school. A target for the bullies because his maternal grandfather was German, he escaped through his friendship with the feral Francie. After the authorities intervened, Carl was separated from both his mother and his friend. Carl had to come to terms with the calamities that had beset his young life if he was to be reunited with those closest to him.

Carl died in April 2023. In his Herald obituary, Dave Manderson commented: ‘His life force was so strong that he seemed indestructible, and it is difficult to believe that his astonishing energy is gone. He may well have had more influence on the Scottish writing scene than any other author. What has never been widely known are the details of Carl’s childhood and the challenges he faced during those years’ – as now revealed in Already, Too Late.

Praise for Someone Always Robs the Poor

‘…the sheer accomplishment of the storytelling and the lively variety of writing styles make it a compelling read.’ DAILY MAIL

‘A towering figure… has lost none of his distinctive style or ability to shock… MacDougall creates a complex world over a dozen deftly crafted pages… [a] masterful collection.’ SCOTSMAN

‘The towering voice of Scottish literature returns with this stunning collection... told without melodrama, with MacDougall’s cleanly-written prose… This is a triumphant return to fiction after an absence of a decade for this award-winning writer.’ SCOTTISH FIELD

‘Brutal but brilliant.’ HERALD

‘Carl MacDougall’s new collection is brimming with the qualities we’ve come to expect from this important Scottish writer: beautiful writing, real people, poignant and wounded like us, rich emotional wisdom, and a lovely wit.’ ANNE LAMOTT, author of Blue Shoe and Imperfect Birds

Praise for The Casanova Papers

‘Absorbing, intense and wonderfully written.’ THE TIMES

‘[A] beautifully realised requiem to love.’ SCOTLAND ON SUNDAY

‘An emotional history of peculiar power and intensity… an exceptional work, mediative and resonant.’ TLS

Praise for Stone Over Water

‘This novel… sets Carl MacDougall firmly among the pantheon of Kelman and Gray… sparkling and exhilarating… wise and, above all, entertaining.’ SCOTLAND ON SUNDAY

Praise for The Lights Below

‘A masterpiece… one of the great Scottish novels of this century.’ GEORGE MACKAY BROWN

By the same author:

Someone Always Robs the Poor, Freight Books, 2017

Scots: the language of the people, Black & White, 2006

Writing Scotland: how Scotland’s writers shaped the nation, Polygon, 2004

Painting the Forth Bridge: a search for Scottish identity, Aurum Press, 2001

The Casanova Papers, Secker & Warburg, 1996

The Lights Below, Secker & Warburg, 1993

The Devil and the Giro: Two Centuries of Scottish Stories (ed.), Canongate, 1989

Stone Over Water, Secker & Warburg, 1989

Elvis is Dead, The Mariscat Press, 1986

Publisher’s Note: In writing Already, Too Late, Carl MacDougall set out to capture the sounds of his world, from Fife to Glasgow and beyond. The idiosyncrasies that characterised his memories of family, friends and relative strangers (including Katie, who frequently says the opposite of what she means) live on in this text; his story could not be told in any other way.

First published 2023

ISBN: 978-1-80425-121-8

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

Typeset in 11 point Sabon by

Main Point Books, Edinburgh

Text © Carl MacDougall 2023

Very early in my life it was too late.

The Lover, Marguerite Duras

EUAN WOULD HAVE been 12 or 13 when we’d been spending our weekends preparing to tackle the West Highland Way.

A friend had given us use of a lovely, slightly leaky cottage through the woods and by the water at the foot of a hill. We found it easily enough, dumped our stuff and, as a treat, walked back to the village to have dinner in the hotel.

It didn’t happen. The hotel was busy. I had a couple of work calls to make, so we bought sandwiches from the post office and I used the phone box.

It was dark by the time we got back to the car. There was no way we could get down the hill, so we gathered the sleeping bags, blankets and stuff and prepared to sleep in the car. This was high adventure. We had a long look at the stars and settled in for the night. I can’t remember, I think the radio was on, but it was as romantic as possible, wind in the trees, owl hoots, the moon disappearing and suddenly reappearing like a magician’s assistant.

Did you do this with your dad when you were wee? he asked.

I told him my dad died when I was six.

So I don’t know how to do this stuff, I said. I never had a dad and don’t know how to be a dad, so I’m kind of making this up as I go along.

He reached across, touched my hand and said, Well I think you’re doing a pretty good job.

I didn’t sleep. We left the car when the sun was rising, had breakfast and settled into the day. Euan found a kayak and paddled around, I sat on a bench by the door, thinking of an afternoon walk.

Around lunchtime he sat beside me, leaned in and said, Are you going to tell me?

I thought about it and shook my head. Not now, I said, but I will.

ForMichael, John and Joanna

Contents

PART ONE: Bankton Park, Kingskettle, Fife

ONE: Kettle Station

TWO: Marie

THREE: Charlie’s Dance

FOUR: Germans

FIVE: Hospital

SIX: Trains

SEVEN: Rest and Be Thankful

EIGHT: Ivanhoe

NINE: The Bait Gatherers

TEN: Love, Marie, 1939

ELEVEN: Sir Bedivere

TWELVE: Kettle Church

PART TWO: 538 Keppochhill Road, Glasgow N1

THIRTEEN: Stragglers

FOURTEEN: 538

FIFTEEN: The Men

SIXTEEN: Compositions

SEVENTEEN: Saved

EIGHTEEN: Blood

NINETEEN: Canada

TWENTY: Fight

TWENTY-ONE: Oban

TWENTY-TWO: Eva and Charlie

TWENTY-THREE: Miss Fernie

TWENTY-FOUR: Brothers

TWENTY-FIVE: Child Guidance

PART THREE: c/o Nerston Residential School, Nerston, East Kilbride, Lanarkshire

TWENTY-SIX: Nerston

TWENTY-SEVEN: Boxing

TWENTY-EIGHT: Night Walk

TWENTY-NINE: Cinderella

THIRTY: Dream Angus

THIRTY-ONE: Francie

THIRTY-TWO: Seeing

THIRTY-THREE: Birthday

Afterword

PART ONE

Bankton Park, Kingskettle, Fife

…hearing the chink of silverware and the voices of your mother and father in the kitchen; then, at some moment you can’t even remember, one of those voices is gone. And you never hear it again. When you go from today to tomorrow you’re walking into an ambush.

The Other Miller, Tobias Wolff

ONE

Kettle Station

I JUMPED TWO puddles and ran up the brae.

My mother shouted, You be careful. And stay there. Don’t you go wandering off someplace else where I’ll no be able to see you.

The Ladies Waiting Room was damp. There was a fire in the grate and condensation on the windows. The LNER poster frames were clouded. Edinburgh Castle was almost completely obliterated and the big rectangle of the Scottish Highlands above the grate had curled at the edges. There was a faint smell of dust.

My mother took a newspaper from her bag, looked at the headline and sighed. Thank God, she said. At least we’re early.

She had been cleaning all day, finished one job and looked around her.

This bloody place is never right, she said to no one. Now here’s a wee job for you, see if you gave the top of that table a polish, it’d come up lovely.

She lifted the teapot from the range, gave it a shake and poured the tea.

My, but that’s a rare wee job you’re making there, she said.

And when the tea was finished she told me not to move: Not a stir. I want you here.

I wandered round the garden, looking for ladybirds or caterpillars under the cabbage leaves. The strawberries, rasps and currants were gone and tattie shaws were stacked on the compost. The smell of burning rubbish clung to the air.

Come you away in to hell out of there and look at that time. We’ll never get anything done this day. Now, what I want is for you to get washed, arms, hands, face and more than a coo’s lick mind, then get yourself changed into your good trousers and jumper; change your socks and you can wear your sandshoes. Then make sure you’re back here when you’ve finished.

When I came downstairs, she looked at the clock. God Almighty, is that the time? Are you ready? Stand there and let me look at you. You’ll have to do. Now, wait you here while I straighten myself out. And would you look at this place. It’s like a bloody midden. Now, stand you there and tell me if a train’s coming.

Are we going to the station?

Stand there and watch. When you see a train, give me a shout.

The railway dominated the back door, kitchen and garden. There was the tree and a beech hedge, a field and the railway line, wonderful at night, when smoke broke down the moon and a red and yellow glow hauled lit carriages and the shadow of a guard’s van.

I knew there wouldn’t be anything for another quarter of an hour, maybe twenty minutes, when the big London express came through. Then the wee train with two carriages and a single engine that came from Thornton Junction and went the other way to Ladybank, Cupar and eventually Dundee would saunter past.

So I watched the yellow flypaper that hung by the kitchen light, watched it twirl in the breeze and tried to count the flies.

Come you to hell out of there. We’re late. We’ll have to hurry.

No matter where we were or what we were doing, we walked by the station every day: We’ll just take a wee look, she’d say. And this is what we’ll do when your daddy comes back. We’ll walk to the station and he’ll come off the train.

Is he coming now? I asked in the waiting room.

No.

Then why are we here?

It’s a surprise.

She’d been standing in front of the fire, her dress lifted slightly at the back to warm her legs. She put the newspaper back in her bag and we moved onto the platform.

And you be careful, she said. I don’t want to see you near the edge of that damned platform.

I was sure we were going to Cupar, but didn’t know why she wouldn’t tell me, for any time we took the train she spoke about it all day, as if it was a treat, standing by the carriage window to follow the road to Ladybank we walked every week.

From Kettle station, the line stretched to infinity, making everywhere possible from this little place, stuck in the fields, bounded by trees, hedgerows and a string of road. It was early afternoon and autumn pockets of smoke hung over the houses.

The station was deserted and everything was still. A porter walked up from the hotel and stood at the end of the platform. He went into a store, took out a batch of packages and envelopes and left them on the bench. A light was on in the stationmaster’s office.

Two women came up the hill. One stopped and looked in her handbag before answering her companion. Two men in army uniforms stood apart and stared across the fields. One lit a cigarette. A man who had just climbed the brae tipped his hat to the women and asked a soldier for a light.

A bell sounded and the stationmaster emerged, locking the office door.

Stand back, he shouted. Clear the platform, please.

Everyone moved and stared down the line. At first there was nothing, then the rumble and the hiss of steam made me slam my eyes shut and start counting. By the time I reached seven, the train was near. I opened my eyes and stood on the bench as the engine passed, surrounded by steam. Light bounced from the polished pipes, the driver leaned from the cab and waved his hat, the funnel belched grey and black smoke and the white steam vanished when the whistle sounded.

A woman waved and I followed her hand till it disappeared and caught sight of a girl standing by the door. She had blonde hair and wore a dark green coat. When she saw me she raised her hand and let it fall. I ran after the train, trying to find her.

I heard a scream as I ran along the platform, felt something grip my stomach and was turned into the air. The stationmaster held me in his arms. My mother was beside me.

Did you no hear me? she said. Did you no hear me shout?

He was excited, the stationmaster said. Wee boys get excited by trains. I suppose he’ll want to be an engine driver?

Was that the surprise? I asked.

No. This is your surprise now, my mother said.

The local train with the wee black engine had drawn into the opposite platform. My mother tugged at my jersey, spat on a handkerchief and wiped my face.

Come on, she said. We’ll see who’s here.

The guard had the green flag raised when a carriage door opened.

He was sleeping, my granny told no one. If Babs hadnae been wakened then God only knows where we’d’ve ended. Don’t let them shift this train till I’m off. Oh dear Jesus, what’ll happen next.

A porter helped my grandparents and closed the door behind them. Aunt Barbara knelt on the platform and hugged me as the train slouched away.

I think you’ve grown, she said.

She’d been away two nights: Off somewhere nice, she said, and back with a surprise.

Where is he? my granny said. Is he here?

Here he is, Mother. Here, he’s here.

My granny pulled me in towards her and smothered me into the fur collar of her coat. Then she ran her hands over my face: Marie; that wean’s no right.

Barbara laughed and my mother shook her head.

He’s fine, she said.

I turned and watched the red lamp at the back of the train fade along the line to Ladybank. My grandfather touched my head, picked me up and carried me down the brae. He smelled of polish and tobacco. This close, I could see he’d missed a tuft of hair on the curve of his jaw beside his ear lobe.

How are you, Carl? he whispered.

Fine.

I’d been warned. Don’t tell anyone your grandad’s German, my mother said.

Why not?

Because.

I only noticed his accent when he said my name. Sometimes, when he became angry, it was more obvious, but the way he pronounced Carl, with three A’s, an H and no R – Caaahl – was different from everyone else.

Watch you and don’t let that wean fall, my granny shouted. You can hardly carry yourself, never mind a wean as well.

This was the start of us living together and suddenly the house was smaller. There were five of us in the three-bedroomed cottage at Bankton Park in Kingskettle, Fife: my mother, my grandparents, Aunt Barbara and me.

Everything changed when my granny came. She was blind and found her way round the house by touch.

Something’s happened here, she said. This is a damp hoose and it’s never been lucky.

For Godsakes Mother, would you gie yoursel peace.

It’s no right. There’s something no right here. Do you know they’re dropping bombs and he’ll no move. I’m telling you as sure as God’s in heaven I’m no going back to that Glasgow till they stop they bloody bombs. There’s folk getting killed. They bombs’d kill you as soon as look at you.

My mother smiled and Barbara squeezed my arm.

Are you there? my granny asked.

He’s here, Mother. He’s got Babs’s arm.

Then how does he no answer me? Marie, I think that wean’s deaf.

TWO

Marie

SHE WOULD GET so absorbed she released what she was thinking by shaking her head, turning away or using her hands to shoo the thoughts before anyone could find them. And she would look at me as if I was a changeling left by the fairies and her own child, the one who was like her, had been taken. My earliest memories are of her naming my features, as if they confused and delighted her, as if she could scarcely believe her own brilliance.

Her hair was fine, soft and downy and her eyes were the palest blue I have ever seen, so light they sometimes appeared clear. Her body was misshapen. She was maybe five feet three or four and had small, angular legs, was stocky, rather than fat, plump or dumpy. But her hair had the wisp of a curl and she kept it short to avoid having to tie it behind the white waitress’s caps she had to wear with a matching apron over her black dress.

They bloody hats makes me look like a cake, she said.

But at least they hid her hair, which was the colour of straw and often seemed darker at the ends than towards the scalp, where it lay, flat and straight across her head, suddenly bursting into a kink rather than a curl, as though it was the remnant of a six-month perm.

God Almighty, she’d say. What the hell do they expect me to do with this? And she’d brush her hair as though to revive it, lifting it from her scalp with her fingers.

God Almighty was a verbal tic, a time-filler, an exclamation and a way of entering speech.

None of her shoes fitted. Her feet were worn running in and out of kitchens. She had bunions and her shoes had a bulge below her big toe. When she died, I couldn’t touch her shoes, couldn’t look at them. There was so much of her in the light, court heel and stick-on rubber soles. One pair were dark blue but had been polished black because it was all she had.

I never knew they bloody things were blue when I bought them, she said, but they must’ve been, for I don’t think the fairies changed the colour o’ my shoes. Well, they’re black now and to hell with it. God knows, it’ll never be right.

This was a conclusion she often reached, that effort was worthless since failure was inevitable. There had been times when her future seemed assured and she told me she had more than she wanted, more than she thought she deserved. But she never got over the loss; and for the rest of her life she guarded against intrusion.

The trouble was time, she said. We didn’t have time together, no what you’d call real time. You could say we were just getting settled, just getting used to each other, him to my ways and me to his when it happened.

She turned her head to the side and shooed the words away. God Almighty, no shocks, no more shocks. Warn me, tell me well in advance, but please God, no more shocks, no like that, though nothing could be as bad as that. Another shock would finish me.

She never trusted happiness, assumed it was temporary, an illusion, or both. She wanted it for other people and delighted in their success, but never embraced the possibility for herself.

It was taken, she said. The Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away, which doesnae leave much room for manoeuvre, never mind choice.

This, like most of her conversation, was a pronouncement, an absolute, a statement rather than a topic for argument or discussion.

She’d wander round the house singing, telling jokes and making herself laugh. And she made me laugh in more ways than anyone I have ever known. Even now, I often laugh when I think of her.

Away and raffle your doughnut, she said, and I am sure her interpretation was literal. Any other possibility would never have occurred to her. Most of her pronouncements were literal. Och, away and shite, manifest frustration or exasperation; and the worse thing she could say about a man was that he was a bugger, again, I am certain, with little or no understanding of what it meant.

When I was ten or eleven I asked about a bugger. She told me it was someone who took to do with bugs, fleas and the like. And she shuddered when she said it.

The closest she came to homosexuality was to call someone a Big Jessie or a Mammy’s Boy. He’ll no leave his mammy, she’d say, there’s a bit o’ the Jenny Wullocks aboot him. This meant he was hermaphrodite, or at the very least suggested behaviour that was neither one thing nor the other. She used it as a comic term, endearing but strong enough to retain distance.

These things were too realistic and realism was never funny. Work wasn’t funny. Hotels were never funny, especially dining rooms and kitchens; though bedrooms were funny, especially when pretension was involved.

A favourite story was of the elderly man who booked into a country hotel with a young woman. As they left the dining room and made their way upstairs, my mother said to another waitress, Aye hen, you’ll feel auld age creepin ower ye the night.

When the girl spluttered, the man told her she should do something about her cough. It could turn nasty and go into her chest. He knew about these things, being a doctor.

And do you do a lot of chest examinations? my mother asked.

Or the woman who arrived with three heavy suitcases. She never appeared for meals and the chambermaid was not allowed into the room. On the third morning the girl’s sense of propriety overcame all objections. She found the woman dressed in a shroud and surrounded by whisky bottles.

I am drinking myself to death, she said.

Then you’re making an awful bourach of it. You’d be better off going away and drowning yourself.

That chambermaid was from somewhere away far away in the north, she said, and had settled in Oban. Her language was Gaelic and she never quite got the hang of English.

Katie got my mother the job in the King’s Arms Hotel on the Esplanade, where she was working when she met my father.

Put a plaster on my bag and make it for Oban, Katie told my mother when they were working in Fortingall. I wish I was back in Oban, for it’s better here than there.

Katie was affronted by a French guest who told her, I want two sheet on bed.

Dirty rascal, she told my mother. What would he want to do that for?

And tell me that poem again, Marie, she asked.

And my mother would recite the whole of Thomas Campbell’s ‘Lord Ullin’s Daughter’ she’d learned in Teeny Ann’s class at Mulbuie School:

‘Come back! Come back!’ he cried in grief,

‘Across this stormy water;

And I’ll forgive your Highland chief,

My daughter! – oh, my daughter!’

’Twas vain: the loud waves lash’d the shore,

Return or aid preventing;

The waters wild went o’er his child,

And he was left lamenting.

And what do you think happened? Katie asked. Did they die right enough?

They were drowned.

Droont, the boatman and everybody, except himself that Lord Ullin one; he was all right, though I suppose he’d miss his daughter right enough. Och, yes, he’d surely feel sorry for the lassock that was dead; and there’d be times too when he wished he’d let her marry the Highland chief after all. Still, that’ll teach him. See, if he’d anybody there that could’ve read the tea leafs, he’d’ve known the lassock was going to be droont.

Katie, who wore men’s boots or Wellingtons and two or three dresses if it was cold, read the leaves on every cup. She read the visitors’ cups without asking.

Och, here now, listen you to me, you’re going to come into money, she told one set of visitors who’d called in for afternoon tea and had no idea what she was doing, but it’ll never bring you any luck.

Your daughter’s going to give you bad news, she told a woman. I think you can expect a wedding.

Now your man’s going to be working away and if I was you I’d keep my eye on him. I’m not saying more than that but I can smell perfume from this cup and there’s crossed swords and a separation that means a divorce, so you’d better be careful.

You’re having an awful trouble with your bowels, she told another party, but it’ll be over in a day or two when you’ve had a good dose of the salts. You could go to the chemist in Inverness. He’s got good salts there right enough. And don’t eat fish. You’ll have an awful craving for a fish tea, but if I was you I’d avoid all fish and any kind of sea thing, or anything at all that’s connected with water, which will mean anything that’s boiled or poached, though you’d be all right with a cup of tea as well, but I’d steer clear of the coffee and the beer, especially stout for that and the coffee are black, as black as the lum of hell.

Is your salmon poached? a visitor asked Katie, who was helping out in the dining room.

Indeed it is not, she said. The chef buys it in Perth.

Marie, what’s that poem about the charge for the light and the men that go half a leg, half a leg, half a leg onwards?

My mother repeated Katie stories word for word.

Language was a constant source of wonder, for she never owned the language she spoke. It was variable and changed according to her circumstances.

In January, 1919, two weeks after her fourteenth birthday, Marie Elsie Kaufmann began her working life as a domestic servant at 1 Randolph Place, Edinburgh. On her first day the housekeeper told her to turn her face to the wall if she passed a member of the family in any part of the house. When the housekeeper found an edition of Robert Burns’s poems in my mother’s room, she burned the book, telling her Burns was a common reprobate and the master would immediately dismiss anyone found with such a book in their possession. She was also told to speak properly and on no account to use slang or common language.

The first time I became aware of her transformation was on a journey to Oban. We were on our twice-yearly pilgrimage and shared the compartment with an elderly lady who was reading The Glasgow Herald.

After Stirling I stood in the corridor, the way my mother said my father used to, imagining wild Highlanders being chased through the heather, strings of red-coated soldiers behind them. I imagined them climbing the high bens, living in damp and narrow caves, fishing in the lochs and rivers, trapping deer and rabbits, occasionally stealing cattle and sheep to survive. I imagined whisky stills and wood smoke.

I remembered standing with my father as we approached Kilchurn Castle at the head of Loch Awe. That used to be ours, he said, but the Campbells took it from us.

I came into the compartment as we approached the loch, where the railway line used to skirt the brown and black water to watch the passing sleepers and stones, and was immediately aware of the change in my mother’s voice. Her sentences were measured and her tone had altered. She spoke softly and pronounced every vowel. And I could tell from her expression she expected me to copy her inflections when I spoke in this lady’s company.

Her natural voice, rhythms and inflections were Scots but she was trying to be English. This was the way she thought English people spoke.

But she never made the whole transformation. There was always the ghost of another voice, another language, lurking in the background. When she spoke what she assumed to be English she distorted the natural rhythms of her speech and obviously used the framework of another language, which pulled her voice in certain directions. There were things she wanted to say but could not articulate in English, or the language she spoke naturally articulated its own meanings, which were often beyond English. It removed her sense of humour and natural, quick wit, often making her seem lumpish and stupid, as though she had a limited vocabulary or was using words and phrases whose meanings she did not understand. It was the perfect vehicle for someone in her position, a member of the servant class. It meant she could not converse with her betters or could only do so on their terms, making her appear intellectually inferior.

And she did it willingly. Often enjoying the process. She gave the impression of another person when she changed her voice. By adopting the voice of another class, she automatically accepted their comforts and values as her own. This emptied her life of its concerns, made her forget who she was as long as the pretence lasted.

I became used to the transformation and didn’t imitate her language, nor did I copy the way she spoke or tried to speak. I simply raised my voice, spoke slowly and tried to pronounce every letter in every word.

It made me ashamed of her. The changes in her voice were so apparent I was sure everyone was aware of them. When she told me to Speak Properly, I knew what she meant and felt everyone would be aware of my background. It made me even more self-conscious, more certain of the fact that someone would tap my shoulder and tell me I had no right to be wherever I was.

My mother pretended her way out of Keppochhill Road. It was easy to escape the constant scrabble over money, the slope in the floor, the rattling windows and crowded house, the shouts in the night and the interminable stupidity of the conversations and concerns. Acceptance, even survival, meant putting a face on it; anyone who lost that pretence was scorned, the drunks and gamblers, the folk who ran away, drowned themselves or went to the dogs: the lowest of the low.

It was easy to pretend life was different, that somehow the concerns of other folk neither touched or affected you, that they were like people who had been crippled from birth, who could neither run nor dance, that no degree of fineness ever touched them and no matter what they were shown, they would never be different. Because she knew better, and had experienced finer living second hand, she was better. That and the fact that there were standards, a line below which one dared not drop. The lesson was obvious and all too familiar, standing in every close and on every street corner.

You did not get into debt, you tried to save something, no matter how little and you bought nothing if you had something that could do. Square cushions were squeezed into round covers, a hairgrip served as a bulldog clip and with every piece of clothing, including my Aunt Barbara’s old blouses which I was assured would make a lovely shirt, I was told, There, that’ll do. Nobody’ll notice.

Though I am sure she went without to buy my clothes when I complained, she was capable of blowing six months’ wages on some triviality, like a wig. Is it all right? she asked. Jesus Christ, it’s no a hairy bunnet, is it? To hell with it, it’ll have to do. It makes a difference. I feel a lot smarter. It’ll do for my work.

Anything for herself had to be justified, though the excuse was often slender.

Consumerism frightened her. She stood outside Grandfare in Springburn and only went in when she saw a neighbour she considered beneath her coming out with two bags of shopping. She wandered round with her mouth open, pausing at every aisle to admire the riches on display.

Dear God, I’ve never seen as much stuff. Look at this. That’ll cost a pretty penny.

And when she did bring home a quarter pound of tea, she opened the packet with a ritualistic zeal and Grandfare became a byword for excellence.

I bought this at Grandfare, she said, producing two or three slices of ham. It’ll be good.

I despised this, never equating the obvious reality of my mother’s life with her attitudes. She voted Tory, firmly believing we needed the man with the money.

Why? Do you think he’s going to give some of it to us or make more for himself? I’d say, and she shooed the idea away.

This was when she’d brought home scraps from the dinner tables. Instead of the left-overs going to the swill, she packed the slices of cold, cooked steak, ham and chicken, petit fours and what she called good butter into her bra and brought them home. Occasionally she brought the remains of a bottle of wine.

This is claret, she’d say. It has to be drunk slowly and savoured. Claret should be served at room temperature, so you let it breathe before drinking it, that means you uncork it and stand the bottle on the table.

Maybe we should put it near the grate?

Don’t you be so bloody cheeky. You’ll be dining in these places yourself some day and you need to know these things, otherwise you’ll get a showing up.

I told her about a street corner politician who’d shouted, Roast for King George, Toast for George King. We want roast, not toast.

I hope you’re not listening to Communists, she said. They’d have no hotels at all, so what’d we do then?

I always knew what she wanted. I would be educated, and enter a profession. This would be a natural transition that would happen without effort, as if my position was temporary; something would happen and my life would begin, my true life, the one I was waiting to lead, my destiny. I had, of course, no idea what this might be, but I knew I’d do anything to take me away from what I saw around me.

Dearie me, the Kaufmanns of Keppochhill Road, she’d say. What are we like? We’ll never get out the bit. Never.

She encouraged me to read. And from the first it fired my imagination rather than provided the education she thought I was getting, especially when I read my granny’s favourite novel: How The Sheik Won His Bride.

The front cover had a drawing of a bearded, turbaned man with pyramids, camels and sand dunes in the background. The back cover was missing. Pages were stapled together, with the title in red and bold black lettering and every chapter was preceded by an illustration.

That bloody story’s no true, my granny said.

And even before I started to read, she asked questions to which she knew the answer.

What was his name again?

‘In far Arabia, Sheik Ali Bin Abu was restless. The messenger had not arrived.’

Is he in his tent? she asked.

‘For four long days he had stood by his tent watching to see if the sands shifted, if a cloud of dust appeared on the horizon, telling him his trusty Salman, whose fine Arab steed was the envy of a thousand bazaars, was approaching. The mission, he knew, had been hard and dangerous, but if it was possible to succeed then Salman would win the day.’

What does the letter say?

So I escaped by dreaming of what my life would be, imagining nothing but escape. It’s difficult to know when or how it began, but from a time soon after my father’s funeral, when life became unbearable, I lived in two worlds. There was what was around me and what was in my head. I escaped into an imaginary world and the springboard was what I read. I lived in books and relived their stories. They came alive, lived in me. Imaginary strangers made me happy or empathised with my sadness and confusion. Even when I did not know what I was feeling or why, when life offered no clues beyond loneliness, they stayed with me, walked beside me and told me just to be still, or when their tragedies were more dramatic, worse than mine, I could sympathise, talk with them and tell them I understood their loss, their misery, bewilderment and even embarrassment. Reality was often closer to what I imagined than to what I had experienced.

And I am sure my mother felt something similar. When she was with her mother, father or sisters she was more like them, more of an adult, except when she was with Barbara. Their intimacy had an intensity I assumed all sisters shared, though Margaret was different. She worked away, spent her summers at Gleneagles and her winters in London and came home at the end of the season, usually with a friend, a woman she worked beside. Margaret and her friends became part of the set up. They came on family holidays.

Mattie Ashton was from Barrow-in-Furness. She and Margaret were chambermaids at the Great Eastern Hotel by Liverpool Street Station. She told me how wonderful London was, how you could get the tube to any part of the city, go round Billingsgate fish market or the Kent orchards, see the Tower of London or Buckingham Palace, and how she and I would ride down Oxford Street on top of a bus that was scarlet, red as a rose.

Every year she promised. She pressed me into her chest and told me we’d have a lovely time.

Don’t haud your breath, my mother said.

Mattie Ashton had what I am sure she would have considered a proper turn of phrase. Her conversations were interspersed with phrases like, I think you are quite correct in making that assumption.

I agree entirely.

It is the most appalling disgrace.

And, In other circumstances I might beg to differ.

What might these circumstances be? my mother asked.

There was a sudden, unusual hush, filled with anticipation. My Aunt Margaret shot a protective look. She clearly felt defensive and was forever making excuses for poor Mattie, who was worried about her weight, wasn’t sleeping properly and had experienced a big disappointment.

When my mother asked if she had been to Furness, Margaret changed the subject; and when my mother persisted, she said, I’m too busy to go away up there. I’ve got better things to do with my time.

And after a particularly arcane pronouncement, which left an awkward silence, she told us Mattie came from a good family had been very well educated.

How can you tell? my mother asked.

No, she told Margaret after another squabble, I don’t dislike her, but I don’t like her either.

What is it you don’t like?

She’s a miserable bitch. I would’ve thought she could’ve contributed something in the way of money for her keep. And if she couldn’t do it, what about you? Are we supposed to feed her as well as put up with her airs and graces just because she’s your friend? No wonder she’s worried about her weight. She’ll no stop eating.

How did you get your finger hurt, Marie? Mattie asked one night.

An accident.

My mother’s right forefinger was permanently bent from the first knuckle. It was the only time anyone outside the family mentioned it.

It happened when I was wee. I wondered what would happen if I stuck my finger in the door, she told me.

And for whatever reason when it came up later, when I was older, she told me there was a row. I wanted the shouting to stop, she said, though she had often implied her childhood was warm and cosy, maybe the happiest time of her life, full of promise, hope and dreaming. But she was capable of editing her experience in ways that weren’t always obvious, so that contradictions became synchronised. Details emerged gradually, simple and unadorned, as though there was nothing more to add, another definite statement.

He doesn’t like you, she said when I complained about my grandad hitting me, I thought for no reason. I accepted it as easily as my granny’s unconditional love and thought he was old and maybe ill.

He doesn’t like you, she said, because he’s never liked me. Never. I hardly remember him saying a kind word to me, though I did what I could, tried to please him till I saw it made no difference. He couldn’t control me. I wouldn’t give in to him. Even when he left his shaving strap out in the cold, so that it froze overnight and became harder and sorer when he leathered me, I never let him get the better of me. And he sees you as the same.

This was when she became herself, when we were together, when she’d dream aloud and tell me her secrets, the first time they’d danced in the Drill Hall, Oban, what my father said and what he wore, what she said, what life was like during the First World War, when she and Margaret were at Balvaird with their Auntie Kate, walking the long road from the farm to school at Mulbuie, where they put up a monument to Sir Hector Macdonald, Fighting Mac, who went to the same school as her and Margaret, how she wished she’d listened when they spoke Gaelic and how she was always top of the class, even though she had marks deducted for bad handwriting, top of the schools in the whole Black Isle and dreamed of university, an education, maybe even to become a doctor, how she had a poem printed in the Ross-shire Journal.

This was long before I met your father, she said.

Meeting my father was the most important event of her life. She would look through the box where she kept her papers and produce a document.

That’s another thing about your father, she’d say.

According to his Certificate of Service, he was a merchant seaman who volunteered for the period of hostilities only, was five feet five and a half inches tall, had a 37-inch chest, black hair, hazel eyes, a sallow complexion and a small scar above his right ear. He was awarded three chevrons and a good conduct badge. He was qualified in first aid and served as an ordinary seaman from 1 August 1940 to 12 November 1945, changing ships 14 times, beginning and ending on HMS Europa. He served on the minesweepers, was torpedoed three times and twice was the ship’s sole survivor.

And when we went for our walks through town, along the terraces of Glasgow’s West End, through Kelvingrove or Springburn Parks, she would name his features the way she’d named mine.

His growth was so heavy he shaved twice a day. He had a high forehead and was losing his hair, with little more than a clump of dark forelock. His jaw was square. He had big ears and a dimpled chin. His hands seemed huge. When he came home from work he scrubbed them with floor cleaner, never managing to free the dirt. He was a handsome man who smelled of Johnson’s Baby Powder, which he used to cool his face after shaving.

Can you imagine what it must have been like for him in the navy, my mother said, having to wear Johnson’s Baby Powder every day?

He combed his hair by the bedroom mirror, singing the Bing Crosby songs he’d heard on radio, ‘Galway Bay’ and ‘The Isle of Innisfree’, or the songs he had known all his life, ‘Teddy O’Neill’, ‘An t-Eilean Muileach’ or ‘Kishmul’s Galley’.

He was born in Ballachulish, raised in Combie Street and Miller Road, Oban and learned to speak English when he went to school. He sang in the Oban Gaelic Choir, danced at the Drill Hall, went to work and never came back.

That was the end of every conversation. And through it all like blood through a bandage were the things she didn’t think she believed.

You wished if you found money or tasted the first fruit of the year. You wished when a baby was born, on the first star of evening or when a new moon appeared; and if you spat on the money or turned it in your pocket when you saw the new moon, you’d be rich. You wished when you saw the first rowan berries, when bread came out the oven, when a frog jumped on a stone, if you saw a midget, a club foot or a humph. It was bad luck to speak going under a bridge, bad luck to cut your toenails on a Friday, to keep a lock of baby hair or bring laurel or lilac into the house. It was bad luck to put shoes on the table, if you saw the moon in daylight or if a cock crowed at night.

If coal fell from the fire, a stranger was coming, but it was lucky if you trod on shite; if your hand was itchy you’d get a surprise; if two people shared a mirror there’d be a row; it was unlucky to throw hair or nail parings in the fire or to change the sheets without turning the mattress; and rain was expected if cows gathered in the corner of a field or the cat washed behind its ears. The hoot of an owl or rap at the window with no one there meant a death in the family.

THREE

Charlie’s Dance

HIS PICTURE WAS in a silver frame beside the clock and below the oval mirror. The blue jug they’d been given as a wedding present with flowers round the lip was at the other side of the clock. Every morning when she lit the fire, showing me how to twist the paper and lay the coal, she dusted and moved them, wiping the hearth and shaking the rug in front of the fire, fixing the cushions, mopping the floor and moving the furniture and ornaments: Just to brighten the place up a bit, she said.

Now the house was crowded, I learned to put things in their place; but the most immediate change came when Granny needed the lavatory.

Take me. Quick, she’d say as she raised her right arm in front of her and I’d guide her through the kitchen, out the door and round past the garden and coal sheds to the closet by the next door wall.

Wait. Don’t you move.

Every morning and three or four times more each day I stood, in all weathers, looking down the garden, past the vegetable plots and compost heap, past the hedge and over the fields to the railway line, trying not to listen, waiting for the flush and crack of the snib.

Where are you? she’d shout before she opened the door.

And back in the kitchen she’d stand by the range, shouting on my mother to make a cup of tea, Afore I freeze to death in that bloody place and you’ve to carry me out of here feet first in a box.

Now there were breadcrumbs on the floor and down the sides of chairs, jam, sugar and tomato seeds stuck to the oilskin table cover and coal dust and splinters gathered on the hearth.

Some furniture, plates and crockery had arrived from Glasgow, a double bed and side tables, the clock with its heavy chime, four chairs and a chest of drawers. Willie Aitken, the village joiner, had made some of our furniture, a tallboy, sideboard and tea trolleys with a desk and chair for me, but everything was cleared. We moved the table to the back wall, making a passage to the kitchen and doors were always open. And spare furniture was moved to the sheds or bedrooms.

With so many changes, we gradually made everything new, the way they do in stories when the poor become rich and goodness survives.

Mum and Aunt Barbara slept in the big bedroom at the front of the house. My grandparents were now in what had been Barbara’s room, but I still had the wee room over the kitchen at the back.

The air became heavy. There was pipe smoke, voices and the plod of the clock. My grandfather spent most of his time reading while my granny sat at the other side of the fireplace, often talking to herself. If a window was open, she’d tell us there was a draught, except in the warmest days of summer when she sat in the garden, shouting for folk to tell her where they were and what they were doing. Every washing day, she told my mother to hang the clothes properly.

The extra washing took two days. Mum and Barbara did the ironing on Wednesdays and the sheets were changed on Saturday mornings.

Every day, Barbara cycled to the flax mill in Cupar. A couple of afternoons a week, while my grandparents slept, for an hour or two life stepped back to what it used to be when Mum and I walked to Ladybank where she changed her library books and bought the paper. When Barbara cycled into the square she’d put me on the back of her bike and we’d freewheel from the station, sit on the dyke till my mother came running down the hill and the three of us would walk to Kettle, no one hurrying home.

Is that the paper in? my granny cried when she heard the door. Thank God, that’ll keep him quiet for a while.

Oh, good, he’d say, feeling down the side of the chair for his glasses and unfolding the paper carefully. Mum and Aunt Barbara made the tea with the wireless on while Granny talked to them or no one.

After tea, I sat on the floor beneath the table, listening to them discuss themselves. My grandfather wore brown boots with highly polished toecaps and leather laces that wrapped round his ankles and tied in a double bow on the side of his foot. He wore dark blue or grey woollen socks and dark pinstriped trousers. His top trouser buttons were always undone and after a meal he undid all his fly buttons and sat with his belly cupped in his hands.

Granny’s woollen slippers had a sponge sole, a little collar that folded over the top and brown glass buttons at the side. Two buttons were missing. The slippers had a dark checked pattern, like a dressing gown, and were worn at the toes. She rolled her stockings down to her ankles. Her legs were the colour of pastry with dark blue veins on her calves and a cluster between her ankle bones and heels. Her right foot was always crossed over the left and her floral crossover apron strings were sometimes loose and hung over the side of the chair.

My mother sat in her stocking soles. Once, I ran my finger along her foot and was sent to bed. Barbara’s shoes were brown leather with a frill patterned tongue above the lace.

I was not always aware of what they were saying, though they seemed to speak about things they already knew.

It was Archie’s first leave and we didn’t expect it. He had a few days’ rest and recuperation at Portsmouth, or maybe it was Plymouth, I can’t remember; but he made his way to Glasgow, God alone knows how, without a pass or anything in wartime. We had two days and he had to go back. I told him I thought I was due and he said, You’re the one who’ll know, Marie. It was the last thing he said before he went back.

Granny shifted before she spoke. She would wiggle herself round to face whoever was speaking and, underneath the table, rock her hands in time to her voice. Was that before the Blitz? she said.

Just before, would that be right?

I cannae mind, though God knows I’ll never forget that bloody Blitz. You’d think the wean would want to stay where he was rather than come into a world like that, bloody bombs dropping everywhere.

It lit the sky, Grandad said. Even from where we were, you could see the fires in the sky and the smoke and smell hung around for days.

The ground shook. There was the screeching, the whistle of the bombs, then the ground shook. Everything jumped. If it was like that for us, what would it have been like for the poor souls who were getting it. Everything jumped, the cups in the saucers and the clock on the wall, they jumped and landed in time for the shock to shudder through you and then it was quiet till the next whistle.

Just think, said Barbara, we used to go to the shows and ride the chairoplanes and big wheel to get scared. But when it comes at you for real, when you know you could die or that somebody’s dying, it’s a different story.

I don’t give a damn, you can say what you like, my mother said, but it was the Blitz that brought him on. After the Blitz he was never the same. He never was right.

I mind you saying that, said Granny.

It seemed to unsettle him. He tossed and he turned and he punched and he kicked. I knew he was coming, though everybody said it couldn’t be right. You even asked me if I was sure I’d been married long enough.

Indeed I did not.

You did, Mother. When I said I thought he was due you asked how long I’d been married.

Don’t be so damned daft. It was me who made you go to the doctor.

After you’d asked how long I was married. And all he said was, Don’t be silly. The child can’t be due. But I’d enough time to get to Oakbank and that was it. Eight weeks premature.

And Charlie jumped the gates, said Barbara.

Granny nodded, That’s right, she said. The hospital was closed and they wouldnae let him in. He was home on leave, God love him, and I told him I’d a funny feeling, so he ran all the way from Keppochhill Road to Oakbank Hospital. And he was the first to see the wean.

Quarter to six, that’s when he was born. My mother was adamant about this. And they wouldn’t let him in, but he jumped the gates and ran round the grounds, chapping windows and crying my name. Where is he? he shouted. I held the baby up to the window and he did a wee dance.

She had wanted her parents to move to Fortingall where she and Barbara worked in the hotel. Her friend Peggy Morrison came down to see the baby. They travelled back together and Peggy looked after me while Barbara and my mother worked.

My grandfather refused to move. If we’re going to get it, we’ll get it no matter where we are, so we might as well be here as anywhere else.

What I want is no to get it, Granny said. And where do you think has the most bombs, Glasgow or Fortingall?

But they clung on and at the end of the season we moved to Kettle.

Peggy came to see my mother two or three times a year. She spent her mornings in the garden, reading or writing into a notebook. In the afternoons she and my mother worked in the garden or walked round the village, took the train to Cupar where we searched for food and when we got home they cooked together and talked the whole time above the radio noise.

It was Peggy who introduced me to rice as a main course, to cauliflower cheese, baked potatoes and meatless salads. She made my first tomato and nettle soups, served kippers with cream, curried rabbit and baked oatcakes to go with my granny’s crowdie.

She listened to the radio, especially comedy programmes, and was full of tales of London, of sleeping in tube stations, of mutilated bodies and bomb sites, of lost relations and secrecy, of parks that now were gardens, of air raid shelters with pictures on the walls and people who stayed in the shelters because they had nowhere else to go. She told us of the children who had been evacuated to Killin and Aberfeldy and whispered stories of land girls to my mother.

Peggy made a story out of everything. Some of her tales went on for days, involving families and journeys, dragons and witches.

My mother’s favourite book was A Man Named Luke by March Cost. She showed me the inscription, ‘For Marie, with best wishes from the author, 1941’, written in blue ink. Peggy wrote that book, she said. And a few others. She gave it to me when I was carrying you.

Damned stuff, my granny said. Who in the name of God is going to believe in that sort of thing?

You haven’t read it.

The best book that ever was written was that other book I like, what’s its name again?

How The Sheik Won His Bride.

Aye, that’s it. Anyway, how in the name of God can I read a book when I cannae see a hand in front of my face?

They’d have a hand or two of whist or solo, singing while they played, with the wireless in the background. And just before the Nine O’Clock News, the kettle would go on for tea and toast and jam before bed.

I never wanted to sleep on my own, always wanted to be with them, fearful of the upstairs dark, the shudder and made up possibilities. Granny’s warnings made me fearful of damp, cold places and l took every chance to stay up late. The stairs were cold when I started the climb and I shivered as I ran into the bedroom and warm bed. I always thought I might hear something I shouldn’t have heard, but it never happened. They just carried on, blethering as before.

Poor Charlie. I wonder where he is this night. He could be lying dead and we wouldn’t even know, him and Willie both, as well as George and that man of Eva’s, what’s his name again?

Matt.