14,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Parkstone International

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

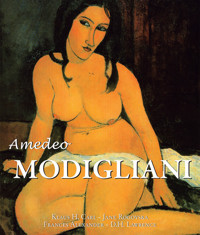

Equally famous for his masterful canvasses and tumultuous mental health, Amedeo Modigliani (1884-1920) was, in many ways, the prototypical tortured artist. A lifelong sufferer of painfully degenerative tuberculosis, Modigliani was famous for denying his disease with a frenzied bohemian lifestyle of hard drinking, drug abuse, and passionate love affairs. But at the same time, he managed to produce some of the modern movement’s most enduring masterpieces, and today his work sells for record-breaking sums whenever it comes up for auction. In this fascinating examination of Modigliani’s life and works, Klaus H. Carl, Frances Alexander, and Jane Rogoyska turn their penetrating gaze on this most enigmatic of artistic geniuses. Their insightful text is accompanied by extracts from D.H. Lawrence’s highly sensual novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover, chosen to complement Modigliani’s art and to give a new perspective to it.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 98

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Authors:

Klaus H. Carl, Jane Rogoyska, Frances Alexander, and D.H. Lawrence

Layout:

Baseline Co. Ltd

61A-63A Vo Van Tan Street

4th Floor

District 3, Ho Chi Minh City

Vietnam

© Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

© Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

Image-Barwww.image-bar.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers, artists, heirs or estates. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 978-1-78310-252-5

Klaus H. Carl, Jane Rogoyska,

Frances Alexander, and D.H. Lawrence

Amedeo

Contents

His Life

His Work

Extracts

Biography

List of Illustrations

Madam Pompadour, 1915. Oil on canvas, 61.1 x 50.2 cm. Joseph Winterbotham Collection, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago.

His Life

Amedeo Modigliani was born in Italy in 1884 and died in Paris at the age of thirty-five. He was Jewish with a French mother and Italian father and so grew up with three cultures.

A passionate and charming man who had numerous lovers, his unique vision was nurtured by his appreciation of his Italian and classical artistic heritage, his understanding of French style and sensibility, in particular the rich artistic atmosphere of Paris at the turn of the 20th century, and his intellectual awareness inspired by Jewish tradition.

Unlike other avant-garde artists, Modigliani painted mainly portraits – typically unrealistically elongated with a melancholic air – and nudes, which exhibit a graceful beauty and strange eroticism.

In 1906, Modigliani moved to Paris, the centre of artistic innovation and the international art market. He frequented the cafés and galleries of Montmartre and Montparnasse, where many different groups of artists congregated.

He soon became friends with the Post-Impressionist painter (and alcoholic) Maurice Utrillo (1883-1955) and the German painter Ludwig Meidner (1844-1966), who described Modigliani as the “last, true bohemian” (Doris Krystof, Modigliani).

Modigliani’s mother sent him what money she could afford, but he was desperately poor and had to change lodgings frequently, sometimes abandoning his work when he had to run away without paying the rent.

Fernande Olivier, the first girlfriend that Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) had in Paris, describes one of Modigliani’s rooms in her book Picasso and His Friends (1933):

A stand on four feet in one corner of the room. A small and rusty stove on top of which was a yellow terracotta bowl that was used for washing in; close by lay a towel and a piece of soap on a white wooden table. In another corner, a small and dingy box-chest painted black was used as an uncomfortable sofa.

A straw-seated chair, easels, canvasses of all sizes, tubes of colour spilt on the floor, brushes, containers for turpentine, a bowl for nitric acid (used for etchings), and no curtains.

Head of a Woman with a Hat, 1907. Watercolour, 35 x 27 cm. William Young and Company, Boston.

Portrait of Paul Alexandre, 1913. Oil on canvas, 80 x 45 cm. Private collection.

Modigliani was a well-known figure at the Bateau-Lavoir, the celebrated building where many artists, including Picasso, had their studios. It was probably given its name by the bohemian writer and friend of both Modigliani and Picasso, Max Jacob (1876-1944).

While at the Bateau-Lavoir, Picasso painted Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), the radical depiction of a group of prostitutes that heralded the start of Cubism.

Other Bateau-Lavoir painters, such as Georges Braque (1882-1963), Jean Metzinger (1883-1956), Marie Laurencin (1885-1956), Louis Marcoussis (1878-1941), and the sculptors Juan Gris (1887-1927), Jacques Lipchitz (1891-1973) and Henri Laurens (1885-1954) were also at the forefront of Cubism.

The vivid colours and free style of Fauvism had just become popular and Modigliani knew the Bateau-Lavoir Fauves, including André Derain (1880-1954) and Maurice de Vlaminck (1876-1958), as well as the Expressionist sculptor Manolo (Manuel Martinez Hugué, 1872-1945), and Chaim Soutine (1893-1943), Moïse Kisling (1891-1953), and Marc Chagall (1887-1985). Modigliani painted portraits of many of these artists.

Max Jacob and other writers were drawn to this community which already included the poet and art critic (and lover of Marie Laurencin) Guillaume Apollinaire (1880-1918), the Surrealist Alfred Jarry (1873-1907), the writer, philosopher, and photographer Jean Cocteau (1889-1963), with whom Modigliani had a mixed relationship, and André Salmon (1881-1969), who went on to write a dramatised novel based on Modigliani’s unconventional life.

The American writer and art collector Gertrude Stein (1874-1946) and her brother Leo were also regular visitors.

Modigliani was known as ‘Modi’ to his friends, no doubt a pun on peintre maudit (accursed painter).

He himself believed that the artist had different needs and desires, and should be judged differently from other, ordinary people – a theory he came upon by reading such authors as Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867), and Gabriele D’Annunzio (1863-1938).

Modigliani had countless lovers, drank copiously, and took drugs. From time to time, however, he also returned to Italy to visit his family and to rest and recuperate.

In childhood, Modigliani had suffered from pleurisy and typhoid, leaving him with damaged lungs. His precarious state of health was exacerbated by his lack of money and unsettled, self-indulgent lifestyle.

He died of tuberculosis; his young fiancée, Jeanne Hébuterne, pregnant with their second child, was unable to bear life without him and killed herself the following morning.

Woman with Red Hair, 1917. Oil on canvas, 92.1 x 60.7 cm. Chester Dale Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Chaim Soutine, 1917. Oil on canvas, 91.7 x 59.7 cm. Chester Dale Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

From Tradition to Modernism

A Reinterpretation of Classical Works

Modigliani’s first teacher, Guglielmo Micheli (d. 1926), was a follower of the Macchiaioli school of Italian Impressionists. Modigliani learned both to observe nature and to understand observation as pure sensation.

He took traditional life-drawing classes and immersed himself in Italian art history. From an early age he was interested in nude studies and in the classical notion of ideal beauty.

In 1900-1901 he visited Naples, Capri, Amalfi, and Rome, returning by way of Florence and Venice, and studied first-hand many Renaissance masterpieces.

He was impressed by trecento (13th-century) artists, including Simone Martini (c. 1284-1344) whose elongated and serpentine figures, rendered with a delicacy of composition and colour and suffused with tender sadness, were a precursor to the sinuous line and luminosity evident in the work of Sandro Botticelli (c. 1445-1510).

Both artists clearly influenced Modigliani, who used the pose of Botticelli’s Venus in Birth of Venus (1482-1485) in his Venus (Standing Nude) (1917) and Young Woman in a Camisole (1918), and a reversal of this pose in Seated Nude with Necklace (1917).

The sculptures of Tino di Camaino (c. 1285-1337) with their mixture of weightiness and spirituality, characteristic oblique positioning of the head and blank almond eyes also fired Modigliani’s imagination.

His distorted composition and overly lengthened figures have been compared to those of the Renaissance Mannerists, especially Parmigianino (1503-1540) and El Greco (1541-1614). Modigliani’s non-naturalistic use of colour and space are similar to the work of Jacopo da Pontormo (1494-1557).

For his series of nudes Modigliani took compositions from many well-known nudes of High Art, including those by Giorgione (c. 1477-1510), Titian (c. 1488-1576), Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867), and Velázquez (1599-1660), but avoided their romanticisation and elaborate decorativeness.

Modigliani was also familiar with the work of Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746-1828) and Édouard Manet (1832-1883), who had caused controversy by painting real, individual women as nudes, breaking the artistic conventions of setting nudes in mythological, allegorical, or historical scenes.

Girl with Pigtails, 1918. Oil on canvas, 60.1 x 45.4 cm. Nagoya City Art Museum, Nagoya.

The Amazon, 1909. Oil on canvas, 92 x 65.5 cm. Private collection.

Discovery of New Art Forms

Modigliani’s exposure to ancient art, art from other cultures, and Cubism influenced his own work to such an extent that he began to break more and more from the classical tradition. African sculptures and early ancient Greek Cycladic figures had become very fashionable in the Parisian art world at the turn of the century.

Picasso imported numerous African masks and sculptures, and the combination of their simplified abstract approach and use of multiple viewpoints were the direct inspiration for Cubism.

Modigliani was impressed by the way the African sculptors unified solid masses to produce abstract but pleasing forms that were decorative but had no extraneous detailing. His interest in such work is illustrated by his Sheet of Studies with African Sculpture and Caryatid (c. 1912-1913).

He sculpted a series of African-inspired stone heads (c. 1911-1914), which he called “columns of tenderness”, and envisaged them as part of a “temple of beauty”.

His friend, the Romanian sculptor Constantin Brancusi (1876-1957), introduced Modigliani to early ancient Greek Cycladic figures. These, along with Brancusi’s own work, inspired Modigliani’s caryatids.

Modigliani was interested in the depiction of solidity, and caryatids as weight-bearing structures unified the concepts of power as well as grace to form the ideal motif.

The details in Modigliani’s caryatids, however, show a modern awareness of sexuality and a desire to render a sense of the fleshy femininity of the figures. Caryatid (c. 1914) has her arms behind her head in a pose more often associated with sleep and foreshadows the pose of Reclining Nude with Open Arms (Red Nude) (1917).

The caryatid narrows at the waist, but her belly and full thighs are massive and reflect her full, round arms and head. Her pose echoes Renaissance use of contrapposto and shows Modigliani’s awareness of the pliability of her flesh and the sensuousness of her fully curved figure.

The Pink Caryatids (1913-1914) have even fuller curves and display a lush use of luminous colour. They are essentially patterns of circles and are highly geometric.

It was the Cubist approach, developing the ideas of Cézanne, that led Modigliani to stylise the caryatids into such geometric shapes. Their balanced circles and curves, despite having a voluptuousness, are carefully patterned rather than naturalistic.

Their curves are precursors of the swinging lines and geometric approach that Modigliani later used in nudes such as Reclining Nude. Modigliani’s drawings of caryatids allowed him to explore the decorative potential of poses that may not have been possible to create in sculptures.

The raised arms of Caryatid (c. 1911-1912) give her a stylised, ballet posture. Apart from her fully rounded breasts and the curving outline to her hip and thigh, she is more angular and lean than most of Modigliani’s caryatids.

Caryatid (1910-1911; charcoal sketch) has a similar angled head and uplifted leg. In Caryatid (c. 1912-1913) Modigliani has emphasised the raised thigh and pointed breast, showing his intention to present the figure as a sexual female.

The Caryatid dated to around 1912 faces the viewer and can be seen as a predecessor of Modigliani’s standing nudes. The geometrising of the figure is apparent, as is the reduction to simple forms.

Caryatid (1913) is a more highly worked version with fine detailing on the nipples and navel. The slight curve of the right leg where it bends at the knee is an enlivening and humanising detail.

The curious patterned lines across her belly suggest necklaces and emphasise the cone shape of her abdomen and the sexual triangle at the top of her thighs.

Standing Nude (c. 1911-1912) no longer functions as a caryatid and is a true nude study, showing an architectural approach to the body. Her folded arms frame her heavily outlined breasts, while her face remains abstract and Africanised.

The sketch of the Seated Nude (c. 1910-1911) is a fully realised nude drawing and shows the completion of Modigliani’s transition from the caryatids to the true nudes. He allows the lines of the figure’s body to swing in a more expressive approach to her eroticism.

Only one caryatid sculpture in limestone, Caryatid (c. 1914), has survived. It is rough-hewn unlike the stone heads, so Modigliani may have abandoned it without finishing it, or possibly left it unrefined to give it a powerful appearance.