9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Parkstone International

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

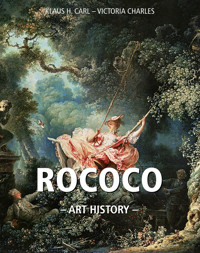

Deriving from the French word rocaille, in reference to the curved forms of shellfish, and the Italian Barocco, the French created the term Rococo. Appearing at the beginning of the 18th-century, it rapidly spread to the whole of Europe. Extravagant and light, Rococo responded perfectly to the spontaneity of the aristocracy of the time. In many aspects, this art was linked to its predecessor, Baroque, and it is thus also referred to as late Baroque style. While artists such as Tiepolo, Boucher and Reynolds carried the style to its apogee, the movement was often condemned for its superficiality. In the second half of the 18th-century, Rococo began its decline. At the end of the century, facing the advent of Neoclassicism, it was plunged into obscurity. It had to wait nearly a century before art historians could restore it to the radiance of its golden age, which is rediscovered in this work by Klaus H. Carl and Victoria Charles.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 60

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Klaus H. Carl – Victoria Charles

ROCOCO

– ART HISTORY –

© 2024 Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

© 2024 Confidential Concepts, Worldwide, USA

© Image-Barwww.image-bar.com

All rights reserved. No part of this may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world.

Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 978-1-63919-847-4

Contents

INTRODUCTION

ROCOCO IN FRANCE

Architecture

Painting

Sculpture

ROCOCO IN ITALY

Architecture

Painting

Sculpture

ROCOCO IN GERMANY AND AUSTRIA

Architecture

Painting

Sculpture

THE 18thCENTURY IN ENGLAND

Painting

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

INTRODUCTION

In the first quarter of the 18th century, in a barely noticeable transition, Baroque gave way to Rococo, also known as the late Baroque period. The unstoppable victory parade of the Age of Enlightenment, which began with the Renaissance and the Reformation continued its unwavering march until the end of the 17th century in England, inching inexorably towards its climax, and throughout the 17th century formed the intellectual and cultural life of the entire 18th century. With this, the educated and prosperous bourgeoisie began to discuss works of art which had hitherto been largely left up to the nobility and the royal courts. If up until that point the clientele for architecture or paintings was drawn predominantly from the church and to a lesser extent from the nobility, and the artists were regarded rather as artisans organized into guilds, they now became individuals with independent professions. At the same time the artist was no longer obligated to create portraits or works based on mythology in accordance with never-changing, prescribed themes and commissions.

The most important instrument of the Enlightenment was prose, which was given a witty, inspirational, entertaining and universally comprehensible form in letters, pamphlets, treatises and historical works, since only these were able to reach the broad mass of the population. In France, between 1751 and 1775, the 29 volumes of the Encyclopédie were published jointly by Denis Diderot, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, d’Alembert and Voltaire. This encyclopaedia encompassed not only the whole of human knowledge but also made available a collection of arguments against the fossilisation of learning.

Absolutism was the norm, in an era in which rulers possessed unbridled power over their territories and were able to govern without any external controls or any obligation to their subjects. This era ended in France around the time of the death of Louis XIV (1715).

François Boucher, The Toilet of Venus, 1751. Oil on canvas, 108.3 x 85.1 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Jacopo Amigoni, Flora and Zephyr, 1748. Oil on canvas, 213.4 x 147.3 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

ROCOCO IN FRANCE

The man who should seek by personal observation of existing works of art to enter into the spirit of the Rococo must travel far indeed: for Paris, though the cradle of that vivacious style contains but fragments of the ancient glory. For precious examples of a noble conception of space he must seek in Versailles and Fontainebleau, for the greatest treasures of artistic French metal work in Nancy, and for remnants of exquisite silver as far as Lisbon or Petersburg – if, indeed, they have survived these troublous times. That unity of exterior and interior, of architecture and decoration, the full harmony of all that Rococo stood for, he can light upon only by travelling eastward across the frontiers of France and visiting the luxurious palaces of princes of Church and State in Germany; for example, Brühl, Bruchsal, Ansbach, Würzburg, Munich and Potsdam. And, finally, for a thorough acquaintance with the furniture of the period he must cross the Channel to the home of Chippendale and his associates.

When Louis XIV died, the field in France was open, and the Rubensists took the lead, bringing forth a style we call Rococo, which – roughly translated – means ‘pebblework Baroque’, a decorative version of painterly Baroque. Rather than a continuation of the style of Rubens, the manner of Antoine Watteau, Jean-Honoré Fragonard and François Boucher conveyed a lighter mood, with more feathery strokes of the brush, a lighter palette and even a smaller size of canvas. Erotic subject matter and light genre subjects came to dominate the style, which found favour especially among the pleasure-loving aristocrats of France, as well as their peers elsewhere in continental Europe.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Swing, 1767. Oil on canvas, 81 x 64.2 cm. The Wallace Collection, London.

François Boucher, Madame de Pompadour, 1759. Oil on canvas, 91 x 68 cm. The Wallace Collection, London.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Blind-Man’s Bluff, c. 1750-1752. Oil on canvas, 114 x 90 cm. Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo (Ohio).

Rococo painters thus carried forward the debate between line and colour that had emerged in practice and theory in the sixteenth century. The argument between Michelangelo and Titian, and then between Rubens and Poussin, was a struggle that would not go away, and would return in the nineteenth century and later. Not every artist succumbed to Rococo. A focus in the eighteenth century on particular social virtues – patriotism, moderation, duty to the family, the necessity to embrace reason and study the laws of nature – were themselves at odds with the subject matter and hedonistic style of Rococo painters. In the realm of art theory and criticism, the philosophers and writers Diderot and Voltaire were unhappy with the Rococo style flourishing in France, and its days were numbered. The humble naturalism of the French artist Chardin was based in the Dutch still-life artistry of the previous century, while Anglo-American and English painters such as John Singleton Copley of Boston, Joseph Wright of Derby and Thomas Hogarth painted in styles which, in different ways, embodied a kind of fundamental naturalism that reflected the spirit of the age. A number of artists, such as Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun and Thomas Gainsborough, incorporated into their paintings some of the lightness of touch that characterised the Rococo, but they modified its excesses and avoided some of its artificial and superficial qualities, however delightful these are.

A leitmotif of Western painting has been the persistence of classicism, and here the Rococo found its fiercest opponent. The essentials of the classical style – a dynamic equilibrium, idealised naturalism, measured harmony, restraint of colour and a dominance of line, all operating under the guiding influence of ancient Greek and Roman models – reasserted themselves in the late-eighteenth century in response to Rococo. When Jacques-Louis David exhibited his Oath of theHoratii in 1785, it electrified the public, and was applauded by the French including the king, gaining an international audience. Thomas Jefferson happened to be in Paris at the time of the painting’s exhibition and was greatly impressed. The popularity of Neoclassicism preceded the French Revolution, but once the revolution occurred, it became the official style of the virtuous new French regime. Rococo was associated with the decadent ancienrégime, whose painters were forced to flee the country or change their styles.