14,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Parkstone International

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

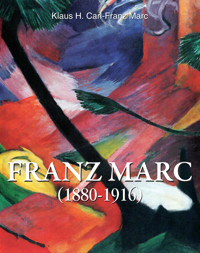

Franz Marc (1880-1916) was a key figure in the German Expressionist movement of the early 20th century. Marc was a founding member of the expressionist group Der Blaue Reiter along with other great artists of the time: Wassily Kandinsky, August Macke, and Alexej von Jawlensky. A brilliant use of colour along with stark futurist and cubist styles create the distinct qualities that make Marc a master of modern art. Symbolising masculinity, femininity, and violence among his calm and bucolic animal subjects, Marc's unique and creative use of colour and meaning will forever have a firm place in art history.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 76

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Klaus H. Carl - Franz Marc

© 2024, Confidential Concepts, Worldwide, USA

© 2024, Parkstone Press USA, New York

© Image-Barwww.image-bar.com

All rights reserved. No part of this may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world.

Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 978-1-63919-880-1

Contents

Germany at the End of the 19th Century – the Imperial Period

Franz Marc and His Life

Franz Marc and Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider)

Franz Marc and Die Brücke (The Bridge)

Franz Marc and The Expressionism

Franz Marc and “Degenerate Art”

Letters of Franz Marc from the Field (excerpts) and some of his Aphorisms

Biography

List of Illustrations

August Macke,Portrait of Franz Marc, 1910. Oil on paper, 50 x 39 cm. Neue Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Berlin.

Everyone who shapes and organises life searches for the right foundation; the rock on which to build. This foundation has only rarely been found within the tradition – often proven to be illusory and fleeting. Great painters do not search for their subjects from amongst those who have been lost to the sands of time, but they instead explore the real and deep focus of their own time. Only in this way can they create their own technique and style of painting.

— Franz Marc

Portrait of the Artist’s Mother, 1902. Oil on canvas, 98.5 x 70 cm. Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich.

Germany at the End of the 19th Century – the Imperial Period

Germany, the victor of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/1871, was ruled by Emperor William I (1797-1888). From his time as Crown Prince, hence before his enthronement as Emperor of Germany and King of Prussia, he was nicknamed “Prince of Grapeshot”; an unflattering name brought about because of his alleged participation in the suppression of the 1848/1849 Revolution, caused by Johann (Max) Dortu (1826-1849) who was later executed for “treason”.

In his official duties, William I, who had reluctantly accepted the position of German Emperor, was supported by Prince Otto von Bismarck (1815-1898). The chancellor was compelled to spend a considerable amount of time on the Socialist Act (the German Anti-Socialist Law which was passed in order to curb the dangerous strength of the Social Democratic Party), thus giving a reason for his dismissal in 1890 under William II. The British satirical magazine Punch of the 29th of March 1890, under the headline of the famous cartoon “Dropping the Pilot” hit the nail on the head.

The Frankfurter Zeitung of the 10th of October 1878 reported on a session of the Reichstag:

Today’s meeting of the Reichstag, in which the debate on the second reading of the Socialist Act, had its start. It turned out to be one of the stormiest and most passionate meetings we have ever witnessed in the Leipziger Strasse. Today’s meeting can be described as a duel between Bismarck and Sonnemann. Probably never before was a more serious and unjustified, or more far-fetched accusation thrust into the face of an elected representative as happened today on the part of the Chancellor towards the deputy of Frankfurt from the stands of the Reichstag – charging him with treason, albeit veiled, which is punishable under the penal code with imprisonment.

In spite of further heated debates, this bill, which corresponded to a ban of the Socialist and Social Democratic parties, was finally adopted in the autumn of 1878 and it remained in force until 1890.

Due to the social hardship that affected most of the workers, it had become an urgent need to counterbalance the negative effects. As an efficacious “sedative”, health insurance was introduced in 1883, thereafter followed by accident insurance a year later, and finally, in 1889, old-age insurance became part of the social legislation.

A further focus of Bismarck’s policy was, as from around the mid-1880s, the initial and half-hearted operation of the colonial policy. After all, Germany was amongst the major powers of Europe (along with Britain, France, and Russia) who had already ruled, for quite a time, over colonies. Finally, in 1884 and 1885, Bismarck was able to acquisition the colonies of Togo, Cameroon, German East Africa, and German South-West Africa. The latter two were initially acquired by two private entrepreneurs. This meant that Germany took part in the race for African colonies, which in the long run would ultimately be deemed unsuccessful.

Another key element after the victory in the Franco-Prussian War was the cultural struggle between the Empire and the Catholic Church under Pope Pius IX (1792-1878). The main issue was the separation of church and state, and to which, as a result, we owe the introduction of civil marriage.

Indersdorf, 1904. Oil on canvas, 40 x 30.5 cm. Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich.

Cottage on the Dachau Marsh, 1902. Oil on canvas, 43.5 x 73.6 cm. Franz Marc Museum, Kochel am See.

Small Horse Study II, 1905. Oil on cardboard, 27 x 31 cm. Property of the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Franz Marc Museum, Kochel am See.

The Dead Sparrow, 1905. Oil on panel, 13 x 16.5 cm. Sammlung Erhard Kracht, Stiftung Moritzburg - Kunstmuseum, des Landes Sachsen-Anhalt, Halle.

For the French, their defeat in the Franco-Prussian War proved costly; they were obliged, after all – besides the loss of Alsace and Lorraine departments – to pay on top of what they already owed, five billion francs in war reparations. This amount supported Germany’s post-war economy significantly. No time was wasted in using the increase in finances for not only replacing previously lost military equipment but also buying new inventions and developing existing technology.

These technical innovations promoted industrialisation and hence the urbanisation and transformation of Germany into a country of immigration for workers from Eastern countries. The innovations were mainly (the following list is not absolutely complete) the electric streetcar (Siemens), the world’s first line of which was inaugurated in 1881 in Berlin; the introduction of electric street lighting in Nuremberg and Berlin (1982); and the steam turbine developed in 1885 by Carl Gustaf Patrik de Laval (1883, Switzerland) and Parsons (1884, Britain); and the first (three wheels) petrol car built by Carl Benz. In the same year, the Viennese chemist Auer von Welsbach developed his approach of gaslighting for mass production, Otmar Mergenthaler invented the Linotype typesetting machine for printing houses (1886), Emil Berliner applied for a patent for the record as a successor of the gramophone (1887), and later, for more comfortable transportation in the Benz automobile, the Scottish veterinarian John Boyd Dunlop invented air-filled tyres in 1890, which was, however, initially only designed and used for bicycles.

As the most important inventions then, as well as today, were primarily designed for a military operation rather than a civilian one, the American Hiram Maxim developed the machine gun as a successor of medieval guns in 1885. The Maxim Gun was employed during the colonial wars against the less skilled and prepared natives, who were generally only armed with shield and spear. It was also successfully used in World War I.

In 1897, on the basis of electromagnetic waves, as detected by Heinrich Hertz, Guglielmo Marconi invented wireless telegraphy. The late 1800s were thrilling and exciting years.

In contrast to his early years, towards the end of his reign “Prince Grapeshot” William I was quite popular amongst the people. This was despite four assassination attempts made on him – two of which wholly failed, the first attempt had slightly wounded his neck, and only the third attempt severely injured the Prince in the head; his life probably saved due to his spiked helmet, widely regarded as a symbol of Prussian militarism. Bismarck primarily utilised this attack to enforce the above-mentioned Socialist laws in the Reichstag. William I died after a short illness on the 9th of March 1888.

One indication of his (late) popularity is the song Fehrbelliner’s horsemen March composed by Richard Hennion, an extract of which was often sung, bawled, or blared at an ungodly hour: “We want to have our good old Kaiser William back.” In order to ultimately avoid imperial confusion, the second and final line of the song continued, “But the one with a beard, but the one with a beard.”

William I’s successor and the last German emperor was a firm believer in divine right. He was the gifted, but occasionally slightly infantile and stubborn, grandson of Wilhelm II, whose father, the Crown Prince Frederick, had died after a short time on the throne. Wilhelm II’s reign culminated in World War I, at the end of which, on the 9th of November 1918, he had to abdicate the throne. The Netherlands granted him, after some hesitation, asylum until his death.

So far, in very general terms, we have the history of the German Empire.