9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Parkstone International

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

The Baroque period lasted from the beginning of the 17th-century to the middle of the 18th-century. Baroque art was artists' response to the Catholic Church's demand for solemn grandeur following the Council of Trent, and through its monumentality and grandiloquence, it seduced the great European courts. Amongst the Baroque arts, architecture has, without doubt, left the greatest mark in Europe: the continent is dotted with magnificent Baroque churches and palaces, commissioned by patrons at the height of their power. The works of Gian Lorenzo Bernini of the Southern School and Peter Paul Rubens of the Northern School alone show the importance of this artistic period. Rich in images encompassing the arts of painting, sculpture and architecture, this work offers a complete insight into this passionate period in the history of art.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 56

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Klaus H. Carl & Victoria Charles

BAROQUE ART

© 2024, Confidential Concepts, Worldwide, USA

© 2024, Parkstone Press USA, New York

© Image-Barwww.image-bar.com

All rights reserved. No part of this may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world.

Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 979-8-89405-000-3

Contents

Foreword

Baroque Art

The Artists

Italy

France

The Netherlands

Spain

List Of Illustrations

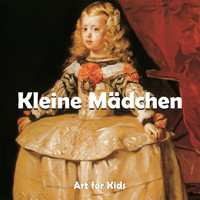

Diego Velázquez,Las Meninas,1656-1657. Oil on canvas, 318 x 276 cm. Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid.

FOREWORD

Baroque art (derived from the Portuguese word ‘Barrocco’ meaning rough or imperfect pearl) originated in Italy and a few other countries as an imperceptible passage from the late Renaissance which ended about 1600. It roughly coincides with the 17th century.

The word Baroque was for a time confined to the craft of the jeweller. It indicates the most extravagant fashions of design that were common in the first half of the 18th century, chiefly in Italy and France, in which everything is fantastic, grotesque, florid or incongruous – irregular shapes, meaningless forms, an utter lack of restraint and simplicity. The word suggests much the same order of ideas as Rococo.

It was occasionally seen as a variation and brutalization of the Renaissance style and sometimes conversely as a higher form of its development, and remained dominant until approximately the middle of the eighteenth century. Conventionally, the Baroque style is not emphasized in the global history of art, because the time period when it flourished — between 1550 and 1750 — is correctly viewed as an enclosed time period in which various directions of style were expressed. The work that distinguishes the Baroque period is stylistically complex and even contradictory.

Baroque art is applicable to sculpture architecture, furniture and literature. The seventeenth century also brought Baroque innovations in music.

Hendrick Ter Brugghen, Flute Player, 1621. Oil on canvas, 71.3 x 55.8 cm. Staatliche Museum, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Kassel.

Simon Vouet, Wealth, 1627. Oil on canvas, 107 x 142 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris.

BAROQUE ART

While Italian Renaissance artists created highly organised spatial settings and idealised figures, northern Europeans focused on everyday reality and on the variety of life. Few painters have equalled the Netherlandish painter Jan Van Eyck, for example, in his close observation of surfaces, and captured more clearly and poetically the glint of light on a pearl, the deep, resonant colours of a red cloth, or the glinting reflections that appear in glass and on metal.

Spanning both north and south Europe during the Renaissance was Albrecht Dürer of Nuremburg. Durer followed the Italian practice of canonical measure of the human body and perspective, though he retained the emotional expressionism and sharpness of line that was widespread in German art. Though he shared the optimism of Italians, many other northern painters were pessimistic about the human condition. Giovanni Pico della Mirandola’s essay on the Dignity of Man presaged Michelangelo’s belief in the perfectibility and essential beauty of the human body and soul, but Erasmus’s Praise of Folly and Sebastian Brant’s satirical poem Ship of Fools belonged to the same northern European cultural milieu that produced the fantastic visions of Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights triptych and Pieter Bruegel’s raucous peasant scenes. There was hope for humankind in paradise, but little consolation on earth for beings consumed by their passions and caught in an endless cycle of desire and fruitless yearning. Northern humanists, like their Italian counterparts, called for the classical virtues of moderation, restraint and harmony – the pictures of Bruegel represented the very vices against which they warned. Unlike some of the contemporary Romanists, who had travelled from the Netherlands to Italy and been inspired by Michelangelo and other artists of the time, Bruegel travelled to Rome around 1550 but remained largely untouched by its art. Instead he turned to local inspiration and staged his scenes amidst humble settings, earning him the undeserved nickname ‘Peasant Bruegel’. Brueghel was a herald of the realism and bluntness of the northern European Baroque.

The great intellectual revolt set in motion by theologians Martin Luther and John Calvin in the sixteenth century provoked the Catholic Church to respond to the challenge of the Protestants. Various church councils called for reform of the Roman Catholic Church, and participants at the Council of Trent declared that religious art should be simple and accessible to a broad public. A number of Italian painters, however, known as Mannerists, had begun developing a form of art that was complex in subject matter and style. Painters eventually responded to ecclesiastical needs as well as to the stylisations of Mannerism. We call this new era the age of the Baroque, which was ushered in initially by Caravaggio. He painted mainly religious subject matter, but in the most realistic and dramatic manner possible, and gained a following among ordinary people as well as among connoisseurs and even Church officials. Caravaggism swept across Italy and then the rest of Europe, as a host of painters came to adopt his chiaroscuro and suppression of vivid colouring; his earthy tones and powerful figures struck a chord with viewers across the continent who had tired of some of the artificialities of sixteenth-century art.