Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

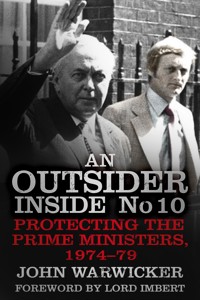

Former Special Branch officer John Warwicker gives the inside story of the six years he spent in charge of security at 10 Downing Street, tracking one of the most turbulent periods in modern British politics. From 1974–79, when the threat of the Cold War and the IRA was ever present, the 'targets' who Warwicker protected daily, both at home and overseas, were Prime Ministers Wilson, Callaghan and Thatcher. More than thirty years on since Warwicker left his post, his insightful memoir, based not only on personal memories and experience, but often also from contemporaneous notes, includes a fascinating and frank insight into the day-to-day operations at Downing Street and Chequers and the eccentric cast of characters within. Despite the constant threat of terrorism that was prevalent at the time, there is a touch of Yes, Prime Minister that runs through the narrative, which adds a surprisingly amusing element to this revelatory book.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 474

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Ann

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The late Detective Superintendent Arthur Smith, Special Branch, kindly gave permission to display the images taken privately on the Scilly Isles and elsewhere when we were serving with Harold Wilson. Thanks to other, later colleagues at No 10 – Colin Colson, Peter Smither, Ian Brian and Ray Parker – for forming a close-knit, well co-ordinated team during sharp-end, often dangerous and always anxious years, and now for their valued co-operation and sure memories. Commander John Howley, former head of Special Branch, is thanked for authorising publication of this manuscript.

Morvyth and Charles Seeley of Rendham in Suffolk unhesitatingly devoted their time and literary expertise on my behalf. Their advice, experience and encouragement proved invaluable in areas of the publishing business not previously well known to me. Their help provided the means of avoiding many obstacles which might otherwise have proved seriously obstructive.

Raymond Carter provided reliable research into targeted episodes of modern political history, where the my failing faculties created log jams. His balanced assessments often provided useful background to otherwise trivial memories. Captain Barbara Culleton, TD, gave a great deal of her time to proofread the draft, often under difficult circumstances. Her attention to detail and fine knowledge of English usage made a major contribution to the reduction of my workload, which often seemed infinite. Barbara Howard also kindly surveyed the manuscript and offered valuable ideas for improvement and coherence. A number of grammar-usage guidelines were suggested by Margaret Aherne, together with kindly encouragement when inspiration was failing.

My wife, Ann, for whom this manuscript was written, died before completion. It is difficult to describe her contribution adequately. While she was still well enough to take an interest, her numerous acquired PC skills were in constant demand thanks, largely, to my own inability to master modern technological opportunities. Her aptitude in preparing and re-presenting elderly and often inadequate images was little short of remarkable, and greatly appreciated by me.

On the final lap, and with papers and records often in disarray, it was fortunate that I was able to meet June Hayes, on holiday from New Zealand. She certainly helped to maintain morale and to unravel the PC chaos into which I had steered myself. Once June had returned home, I leaned heavily upon Richard Harris, who offered talented and practical help with production and systems control of the final manuscript. This proved especially invaluable, as my remaining eyesight continued to fail after I had formally been registered severely sight disabled.

When writing a book, certain procedures - such as the creation of an index - cannot usually be completed until a final draft is agreed. Similarly, requests for the provision of a foreword cannot be solicited until the full content is available for inspection. At an appropriate time I was fortunate to rendezvous with Lord Imbert (at Lady Thatcher’s funeral in St Paul’s Cathedral). We had once worked in Special Branch at similar levels, and then he shot away climbing speedily from rank to rank, eventually to become Commissioner of London’s Metropolitan Police – and much more. In spite of years combating ill health, Lord Imbert retained an active interest in the nation’s affairs and the progress, or otherwise, of his former colleagues. When approached, he kindly agreed to provide the foreword for An Outsider Inside No 10. I am greatly honoured and thank both him and Lady Iris.

A number of individuals and institutions, knowingly or unknowingly, have provided the images included. A conscientious amount of trouble has been taken to establish origins and copyright commitment. However, there has been a considerable passage of time since they were created and, where credit is considered inadequate, apologies are willingly offered.

The difficult tasks of last proofreading and indexing largely fell upon the competent secretarial shoulders of Jill Sullivan, a friend of many years, whose timely entry into my life after almost a decade of residence in Ibiza could hardly have been more opportune. I am grateful for her patience and skills and also to those of the numerous individuals and Institutions who offered essential help with publication and the use of modern technology. These included, from The History Press, Commissioning Editor Mark Beynon and Editor Rebecca Newton. Peter Palmer was often called upon to lift me out of the IT minefield into which I had become marooned, and so was Paul Nugent and the charity Action for Blind People, which he represents, and the personnel of Blind Veterans, formerly St Dunstans, all co-operated with the utmost kindness and willingness.

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Preface

Introduction

An Outsider Inside No 10

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Bibliography

Plates

Copyright

FOREWORD

by Lord Imbert

Few of we ordinary mortals know what is happening behind the sturdy and well-guarded doors of No 10 Downing Street or who the people are who have official or even informal influence on the players who inhabit this residence: the prime minister and others who have the power to change our lives, indeed, to change the country and the world.

But one fly-on-the-wall who watched, listened and saw the human nuances and touches which had an otherwise unseen influence on those major players was John Warwicker, the Metropolitan Police Special Branch detective superintendent who, for almost six years, from Harold Wilson’s second administration to Margaret Thatcher, was in a unique position to see behind the curtains and record the domestic and day-to-day incidents which shaped the lives of these powerful figures who in their turn shaped the daily lives of millions of we ordinary folk.

This is a most interesting, intimate, amusing and readable insight into those apparently everyday matters which – put together as John Warwicker has done so candidly – shows that behind the invisible and metaphorical iron facade of No 10 Downing Street are human faces. Who else would have sheltered under an upturned boat keeping the then prime minister and his wife from the worst of a Scilly Isles downpour or been with the same prime minister queuing for his breakfast sausages in the local Co-op.

John Warwicker, in the mould of a typical British Special Branch protection officer, gives away no state secrets, nor would we expect him to. But he gives us a most readable insight into the daily lives of those who run our country and also have the power to influence world events.

A splendidly informative and amusing peep behind the scenes of No 10.

Lord Imbert The House of Lords

PREFACE

A ten-minute walk across St James’s Park took me from New Scotland Yard, into Downing Street, and provided distinguished names to drop should I ever be persuaded to write about it.

The year was 1974, Harold Wilson was the prime minister and the public could still stand outside No 10 and point, gasp and giggle whenever they saw someone they recognised from television or the newspapers.

My mission was not a happy affair. I was about to be transferred from a posting as deputy head of the counter-terrorism squad of Scotland Yard’s elite Special Branch and moved sideways into a downmarket, pinstriped backwater. The branch had reshuffled its four-man team of armed, close protection officers at No 10 and someone had suggested my name as a replacement for the No 2 slot. Having made waves inside Scotland Yard, perhaps it was an opportunity to transfer me into no-man’s-land.

The decision now was in the hands of the prime minister, as he bustled in from the House of Commons. He was introduced by Detective Superintendent Arthur Smith, the experienced officer then in charge of his close protection. Mr Wilson asked a few, low-key questions to someone apparently hovering over my left ear. After a short hiatus I realised he was speaking to me, if not at me. It was my first lesson of life with this PM. He rarely looked you straight in the eye until he had decided – even with little to go on – that you were to be trusted. In an environment where leaks were endemic – mainly, it was said, from the PM himself – the ability to remain close-mouthed was important both for him and State Security. I was to discover the fallibility of some of his judgements as I became acquainted with his political cronies.

He nodded and marched off down the corridor leading to the Cabinet Room and I was enrolled into the No 10 network, under the unhappy impression that I was in for an uninspirational time.

Nearly six years later, and through the succeeding administration of James Callaghan and Margaret Thatcher’s first year as well, I realised just how mistaken that foreboding had been.

INTRODUCTION

To work for a Prime Minister is a privilege only less than being Prime Minister himself. It compensates for the temporary destruction of one’s private life; in return for total commitment it offers continuous excitement. To enjoy it to the full, it should never be out of one’s mind that the job is, at best, temporary.

Joe Haines, The Politics of Power, p.9

Political leaders worldwide are obsessively insecure – even in stable western democracies such as our own – and haunted by the threat of losing their power base and an honourable place in history.

Within the United Kingdom their crisis may be within parliament or without. If within, there is not much the democratically committed Metropolitan Police Commissioner or his Special Branch can, nor should, do about it. But if a revolutionary tendency deploys unconstitutional violence, and appears to spearhead a breakdown of established order, the civil police could then be obliged to pre-empt or proscribe it by the use of Intelligence or counter violence. The departure of elected leaders, even legally, is potentially destabilising. When Harold Wilson resigned as prime minister in 1976, that ever-watchful extrapolation into the future, the Stock Exchange Index, sagged by nearly 10 per cent against the unlikely chance that a breakdown of organised government would follow.

The risks would be greater still if change at the top was accompanied by violence. The full-time task of improving the odds by protecting certain Cabinet Ministers (and, for broader reasons, foreign heads of state) traditionally fell upon Special Branch.

During inter-war years, Intelligence communities worked out gloomy worst-case scenarios, forecasting the possibility of disorder following an orchestrated, perhaps Bolshevik-inspired, revolution. With the Soviet uprising in 1917 as one example, the British Establishment was not exempt from these concerns. Indeed, the United Kingdom itself was sometimes on the brink during the 1920s and ‘30s.

In the event, little happened in the United Kingdom to disturb the status quo until the 1970s, but it was hardly a secret that government-funded counter vigilance was maintained both overtly and in various guises, to check upon extreme, politically motivated groups suspected of aiming at the overthrow of a lawfully elected government. It was here, again, that Special Branch – at least until its disbandment in the new millennium – worked pro-actively in concert with the government secret services, MI5 and MI6.

With the exception of members of the royal family, the prime minister was most vulnerable to assassination or abduction. Having the benefit of both a national Intelligence-gathering role and some small arms and Close Quarters Combat training for its teams of bodyguards, Special Branch was, on paper at least, well equipped to provide protection. Other politicians regarded as potential targets were the Foreign and Home Secretaries and the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland. For some reason never made clear, the Chancellor – who was certainly not universally adored – was not on the target list drawn up by risk assessors. Members of the royal family, not to be sullied by association with a politically oriented unit of the police service, were the exclusive preserve of Uniform Branch, although their appointed officers worked in plain clothes.

Although the traditional political right regarded the police service as an arm of the Conservative Party, and the far-out left of the Labour Party to view it with little better than sneering hostility, it is clear from history that not only were the appointed Special Branch protection officers able to forestall or prevent any major incidents against their various charges, but that they did so, in the main, with commendable impartiality. The fact is that where public officials were known to have close protection, terrorists preferred to look for softer targets.

It was not all good news for me, however. The problem was that our team was crucially underfunded, undertrained and under-resourced for weaponry and communications. Once I had been promoted to take charge, the fault lines showed just how disadvantaged we were against the escalating threat from terrorists, by overheated and over strident students and politically or racially motivated extremists.

Above all, the rules of engagement in the United Kingdom were rapidly being rewritten by the Provisional IRA. It all signaled a necessary end to protection by portly men in homburg hats and displays of bulging waistlines.

As long as danger to a prime minister was confined to the occasional, demented schizophrenic who had lost his pills, or an isolated hysteric with a grudge against the government of the day, our protection teams, if alert enough, could hitherto usually sort it on the spot. Both the Home Office and Scotland Yard were happy with low-profile cover – uncontroversial and inexpensive as it was. Even before the days when Islamic extremism was activated worldwide, it was clear to those of us in the firing line that Special Branch was not always ahead of new threats. Our experience with protection teams abroad confirmed their intense concerns, and to deal with them they developed impressive counter measures.

In General Orders for the Metropolitan Police, many hundreds of pages were devoted to the methodology of dealing with every imaginable contingency. Under the title ‘Runaway Horses’, for example, officers were still instructed to ‘run in the same direction as the horse’. Just half a page dealt with close protection. It was clear enough that the academic, desk-bound authority which created General Orders, any breach of which was a disciplinary offence, had deliberately avoided committing themselves in the controversial and unpredictable field of armed protection. If it went wrong they were not going to be responsible.

So, if still alive, it was down to the protection officer. It may be argued that while this gave the officer unlimited scope to make up the rules as he went along, he had no cover when something went wrong and bodies were bleeding in the gutter. This gave the job a special glow of insecurity. Everything depended upon minimal threat. As terrorism escalated, this was clearly not good enough.

I was never to win the battle with the British authorities and for a while we remained the western security world’s poor relations. But soon after James Callaghan replaced Harold Wilson as PM – and thanks to timely opportunism by my No 2, Detective (then) Chief Inspector Colin Colson – higher level official interest became focused on the problem too. The outcome supported our concerns; results were immediate and impressive.

Communications, transport, electronic defensive facilities, bullet and bomb proofing and administrative support quietly came our way. Plans were drawn up for new, more suitable limousines. The existing batch of Rovers were all well past sell by dates; rust was visible and interiors pockmarked with cigar and pipe ash. The elderly limos, whose underpaid drivers had only the most cursory evasive training and were not subject to our authority, were conscientiously maintained by Government Car Service, but increasingly fallible.

Home Office boffins had installed non-portable, overweight radio sets with which we could, if given time to find and dial the appropriate code for the district we were in, make contact with any police HQ in the UK. In theory at least, as long as we had a fully equipped limousine, or were in a train with a compatible radio set installed, the PM could be contacted in an emergency through this network. As far as I could see it was the only way for him to activate the four minutes technically allowed to set the nuclear deterrent into action. Perhaps there was no better than a fifty–fifty chance it would work harmoniously at critical times.

It was against this background that I entered into the Downing Street machine. For nearly six years I was able to assess many of its merits and demerits, and to be a small part of a fascinating institution – a small cog in a smooth wheel. My determination to remain politically impartial was respected. Smart footwork was often useful in an institution so intimate and personal that idiosyncrasies were impossible to hide, but it was never necessary to compromise standards, and only rarely to solicit favours. An understanding of operational imperatives was accepted by men and women whose careers would be entirely office bound. Support from the prime minister was always important, but, lest it might be forgotten, even more critical was full back up from resident civil servants, unencumbered as they were by the demands of a public image.

In return, I loyally kept most of this great experience to myself for more than thirty years. I hope that this volume does justice to all parties, but makes no apologies for opinions expressed as a result of my own experience, perception or even partial understanding. Some identities are omitted or disguised whenever the danger of causing offence becomes an important issue. I hope it will be clear to the reader that a policy of objectivity has been maintained, for I was rarely, if ever, the victim of personal animosity or malice during my term as an outsider inside Downing Street. The need for firmness in some areas seems to have been fully understood.

Three politically bruised, but physically unscathed prime ministers, survived during critical days and that was, it seems fair to claim, the bottom line!

An Outsider Inside No 10

ONE

Rule One? Keep belly full: bladder and bowels empty!

Detective Inspector Harry Gray, Veteran Protection Officer

Westminster and Whitehall are awash with history and it is no coincidence that Downing Street stands in their midst. With a wonderful heritage and some distinguished buildings, it seemed strange that, not unlike parts of otherwise glorious Greenwich, so much souvenir-shop tat and fast food was allowed to proliferate. In the 1970s, it was almost impossible to find somewhere decent and reasonably priced to eat in the locality and, without facilities within No 10 itself for anyone other than a select few, the rest of us lived on an unhealthy diet snatched from coffee and burger stalls. On really bad days, when there were no other pressures, the detectives might walk over to Scotland Yard. The canteen manageress there was trying to wean the troops away from the pies and trash diet which had dispatched so many healthy young policemen to the convalescent home at Brighton. Some never to return.

With republican sympathies, George Downing’s family emigrated to America in the early 1600s, but, sensing that times they were a-changing, he returned to Britain during the Civil War and acquired Oliver Cromwell’s blessing as his scoutmaster – or head of intelligence. Downing, with an opportunist’s eye for a chance, noted the prospect of a great future for the Westminster area, in which the palaces of Westminster and Whitehall held the seats of monarchy and government and were situated directly alongside Britain’s religious epicentre, Westminster Abbey. Perhaps he even saw a future for burger bars and tourists too but, in any event, Downing secured from the Commonwealth Parliament the right to redevelop Royal Cockpit Street with affordable housing. Those were the days when developments were already taking place, originals of which are now just names: Scotland Yard, the Royal Cockpit itself and Spring Gardens, for example.

Downing’s plans suffered a credit crunch when the Stuarts were restored in 1666 and his rights declared void. Not a man to jeopardise his balance sheet, he successfully ingratiated himself with Charles II mainly, it is reported, by deploying the duplicitous self-interest not unexpected from an intelligence officer by changing sides and informing on his former parliamentary and republican comrades. This had two effects: they were executed and Charles II, instead of giving him an MBE, restored Downing’s planning permission. Work on the construction of fifteen speculative quality town houses started in 1680 and was completed four years later. Downing failed to benefit; that was also the year he died. No doubt some surviving parliamentarians started to believe in God.

A few years earlier, Charles II had granted a site at the back of No 10, Royal Cockpit Street to his daughter (the Countess of Lichfield), her husband, his senior courtier and master of horse. A high-quality residence was built for them overlooking Horse Guards Parade. For nearly fifty years the residents of No 10 and Lichfield House talked to one another over the garden fence and probably grumbled about the difficulty of finding an honest plumber.

In 1732, the second of the Hanoverian kings, George II, offered the ownership of Lichfield House to his principal minister, Sir Robert Walpole. As Sir Robert was also First Lord of the Treasury, this very much smacked of bribery and corruption, which it probably was, and he sensibly declined the offer as a personal gift, but did accept it as a residence for the First Lord of the Treasury. Lichfield House was joined to No 10, Royal Cockpit Street, by a purpose-built corridor. At the same time, the composite unit was renamed Downing Street. It is still the gift of the First Lord of the Treasury, confirmed by a brass plaque outside No 10.

This brief history accounts for the disparity between the front of No 10 and the back. Speculative housing facing on to Downing Street is joined by a corridor leading to the posh quarters at the rear. These still overlook Horse Guards Parade. It was the posh part that the IRA targeted with home-made mortars in the 1990s, one day when the Cabinet was meeting under John Major. This assault really tested their individual fortitude. It is said that a few of them failed. Perhaps it was simply the problem of eyeball-to-eyeball contact with their party rivals while in a submissively crouching position under the Cabinet Room table as the IRA mortars exploded nearby.

‘Call me Tom,’ said Lord Bridges, Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) adviser to the prime minister and second-in-charge of Private Office. ‘Everyone here is known by his first name. Welcome inside No 10.’ He turned a page of the voluminous dossier on his desk and was obviously anxious to get back to business.

‘Well. Thank you – er – Tom.’

Even junior NCOs in the Royal Marines had insisted on being addressed – preferably very loudly of course – as ‘CORPORAL!’ and I had not expected to be invited to call a lord of the realm by his first name. But Tom was right. That was the protocol in Downing Street. It had little to do with the prime minister and everything to do with the Principal Private Secretary (PPS), the focus of efficiency, dedication and morale in an often frenetic environment.

Arthur Smith had taken an early opportunity to introduce me to Private Office personnel – a PPS, five private secretaries, and appointments and duty clerks. Robert Armstrong (now Lord Armstrong of Ilminster, Secretary to the Cabinet from 1979) was overlord and he had responsibility for the efficiency and co-operative support which all the civil servant staff in No 10 were required to provide for the incumbent prime minister. He ensured, after an initial careful selection, that everyone worked to their maximum ability with a combination of energy and quiet efficiency. A mistake or two was permitted but not carelessness, laziness or disinterest. The back door to lesser offices was always open for staff who failed to match up. He was known to all as Robert, but no one was foolish enough to abuse this familiarity and mistake him for a soft touch.

The Treasury representative private secretary was Robin Butler, later to become PPS under Margaret Thatcher and then ennobled to spend a distinguished retirement as one of Whitehall’s ‘great and good’. And so it came to pass that here was the unique, elite Whitehall group of Oxbridge (Hons) – or the equivalent, if there is such a thing – often with aristocratic heritage and probably voting Tory, who were responsible for organising all the services and information upon which the prime minister of the day depended, and to do so independently and irrespective of the party in power. Personal political preference was not allowed to show, or to influence their judgement. Impartiality was mandatory and only the highest calibre of applicant got the job. Should they survive the – usually – three-year posting, these young men could expect a glowing future with a serious prospect of taking top jobs in Whitehall departments, and eventual knighthoods. The system proved its worth when, for example, Robert Armstrong, who was PPS at No 10 to Edward Heath, remained in post as Harold Wilson took over after the February 1974 election.

This admirable administration buzzes secretly along, invisible to the public and unacknowledged by the media; it should be the envy of the world and probably would be if more generally advertised.

In a way, a private secretary’s failure at Downing Street was tolerated with understanding within the civil service, where the stressful hazards of a difficult posting and the unfairness occasioned by temperamental outbursts from some prime ministers were recognised – providing, of course, there was never a hint of corruption. The Private Office task – to feed the prime minister with the very highest grade of information and to co-ordinate his programme with the party, press and public relations departments, the prime minister’s family, the diplomatic service and much more – demanded 24/7/52 application. Considerations such as unsocial hours, family demands and even minor illnesses were marginalised as irrelevant.

If you followed the delicate machinations in the Yes, Prime Minister series on television you won’t be far out.

During briefings from some of my predecessors – Arthur Smith was not among them – total detachment from Private Office was the recommendation. However, its influence both in Whitehall and with the prime minister was almost absolute, and it very soon became obvious that my own responsibilities could not properly be undertaken without Private Office backing. A decision to work in concert with private secretaries and their subordinates, rather than in isolation, soon proved the best way to live happily ever after. Reliance solely on the close support of the prime minister and the vicarious authority implied by our inevitably close association – especially when away from the confines of No 10 – was not something necessarily to be relied upon. Yes?

Within Private Office, wall clocks indicated the local time in Washington, D.C., Peking (in those days), Paris and Moscow. Profound paperwork, including drafts for some of the prime minister’s forthcoming speeches, was constantly interrupted by staff comings and goings – messengers, secretaries, drivers, detectives, clerks, curators, ladies with cups of tea – but it was wise not to hang around. Telephones were in constant action, with incoming calls identified by flashing lights instead of an intrusion of bells. Activity, often frenetic, was conducted as quietly as possible. Here was the focal point of the prime minister’s official staff, amalgamating data from other Whitehall departments, the Foreign Office, of course, the secret services, Buckingham Palace – the whole world really.

Downing Street was adapted but never custom-built for such intense activity. The secretariat was down in the basement. Paper communications were transferred around Whitehall through puffing and popping old-fashioned compressed air pipes more commonly seen in department stores. In the 1970s not a single computer was in sight. An open office for the PPS adjoined the Cabinet Room, where the prime minister might be working in preference to his first-floor study which was on one side, while that of the private secretaries was on the other. Communication was constant. They overheard telephone conversations and talked to one another to exchange information. The idea was that while each was absorbed in his own batch of tasks, they all became aware, peripherally if not in depth, of what the others were working on. In this way, whichever one was next summoned, he could update the prime minister on all-round progress. They therefore had to be both single-minded and at the same time in touch. Undiagnosed schizophrenia was helpful.

Oiling the works with efficient telephone communication was vital for everyone in No 10. In the 1970s this facility was based on archaic old-fashioned switchboards, with plugs and leads slotted home by up to four ladies at any one time. Pre-war GPO headsets left them both hands free for the slotting. Every incoming call, internal or external, had to be answered and dealt with, IMMEDIATELY. It might merely be a cleaner needing to talk to a supervisor; or Buckingham Palace or the ambassador in Washington. There was no question of being put on hold, or of listening to Vivaldi, or hearing automated dialling instructions. Nor was there any attempt to persuade a caller to ring off. The brilliant, dedicated, intelligent ladies handling the plugs somehow rarely kept you waiting, never left a caller in the dark and – uniquely for switchboard staff – were on no occasion the cause for complaint, not even from fractious troublemakers looking for a scapegoat.

The ‘friendly’ US Embassy in Grosvenor Square sometimes asked these operators for off-the-record help when their own integrated, computerised, automated, infallible system direct from NASA failed to secure contact with – say – the Second US Secretary in Bangkok. Or Vladivostok. Our No 10 ladies would follow a sure pathway to wherever by referring to the stationery office notebook, the bible in which all those little idiosyncrasies of any electronic network were faithfully recorded, and painstakingly updated every quarter by hand with pen and ink. They probably saved us all from the total destruct button on many occasions.

And this performance, incredibly, took place in the triangular attic directly under the sloping, tiled roof. Apparently the demands of security created a need for these special working conditions. I suppose it may have been preferable to the basements in which secretaries in our embassies behind the Iron Curtain had to work with their typewriters, sitting under canvas like Girl Guides. Tents were said to deaden electronic transmissions capable of being intercepted and read by the Russian secret services.

No direct telephone calls, internal or external, were allowed to the staff within No 10. Everything passed through the switchboard. There were no mobiles in those days of course and self-dialling was not available. Call it security or call it eavesdropping, if you will. We assumed every call was monitored.

The cramped and sometimes bent-over circumstances in which these admirable ladies had to work were the probable cause of the permanent list to starboard which identified the taller ones.

Old-fashioned though all of this was, I suppose it was a notable advance from the days when Harold Macmillan was prime minister. He often spent weekends at his country house, Birch Grove, where the only telephone was an upright version with separate earpiece in his housekeeper’s office next to the kitchen. On the occasions when he needed to, he ran Great Britain from below stairs.

In the 1970s much of the work in Downing Street was carried on in the most unsuitable, uncomfortable circumstances, which would have been the cause of a work-to-rule in industry or commerce. Central heating was archaic and air conditioning non-existent. An absence of sunlight created a claustrophobic atmosphere both inside and out.

Nevertheless, organised, fast-lane excellence was demanded from all the staff, irrespective of their nominal standing in the pecking order. Incredibly, it seemed to work. Somehow.

Members of the Special Branch team were collectively referred to as ‘the detectives’ and, while an active part of the total product, they stood independently just outside the civil service arena. However, it was not sensible to remain isolated or dissociated from the collective effort. Our work might have been more practical, less academic, but it was still an essential part of the total No 10 machine, the smooth working of which will frequently be under discussion in this book. As long as our own tasks were not undermined, we pooled our efforts with the others. In the case of the custodians and police officer inside the front door this sometimes amounted, when they were stuck, to help with The Times crossword; however, on most days they had the edge.

But it seems wise to point out at this early stage that everyone – politicians, aspiring prime ministers, journalists, interviewers, researchers, critics or everyday loud-mouthed bigots – should have some idea of how our nation is run. It is not all warts and the occupants in No 10 are not fools. Take care before trying to pretend that they are. Until you are in there, you will not have much of a clue. The problem for No 10 personnel is that they never get around to talking about it themselves, but there is no reason why I should not call for three cheers on their behalf.

Of course, not everything was perfect.

In my experience new prime ministers, and especially new PMs’ spouses, decide not to live at No 10. It never works. A prime minister’s workload is so high that not a minute can be wasted on travelling back and forth. Moreover, questions of security and instant communication make anything other than residence on the spot an impossibility. Newly elected prime ministers also naively decide not to use Chequers at weekends and for holidays. Although Mrs Wilson did put her foot down and insisted upon family leisure time at her bungalow on the Isles of Scilly, Chequers, too, soon became a regular retreat from the harassment that was inevitable within Downing Street itself. Moreover, for the housewife-in-a-pinny image favoured by some spouses, and at least one prime minister, the abundance of skilled and willing staff at Chequers becomes irresistible.

Residence in No 10 can be handed down through the Treasury pecking order if a prime minister decides not to live there. In theory, it could be the home of a Treasury clerk if no one above him wanted it. One example was that of Tony and Cherie Blair who, after the election of 1997, needed more space for their young family than No 10 had on offer. So an exchange was affected with the Chancellor, Gordon Brown. The Blairs got the better of the swap; No.11 is altogether more comfortable, and in my time was also better furnished. It was also a critical few metres further from Private Office and fleet-footed duty clerks, ever-ready to present out-of-hours papers for the immediate attention of the prime minister.

The Right Honourable Harold Wilson, Member of Parliament for Liverpool (Huyton), was in his second prime ministerial administration when I arrived at No 10. The Conservative, Edward Heath, served as prime minister in between and when he left after a narrow defeat in February 1974, the relocation of his grand piano into private premises highlighted one of many problems associated with trying to run the country from unsuitable premises.

His valuable piano was on the first floor at the rear and had to be removed by specialists. The only entrance/exits to No 10 were the recognisable front door, then still in full view of the public twenty-four hours each day, and the back-garden gate onto Horse Guards Parade. It was more of a problem to co-ordinate the resources of the watchful chief security officer himself, the specialist piano removers, No 10 custodians and uniformed police – all in darkness and going about their work in the hope of maximum discretion – than to cross a river in a canoe with a goose, a fox and a bag of corn.

Under normal circumstances and for reasons of security only the front door was in use.

It was guarded by armed, uniformed officers outside and in, and under joint control with the doorkeeper, a civilian employee. It was not large enough to get a piano through in the horizontal position. Neither was the garden gate at the rear, the keys to which were restricted to detectives, the housekeeper, Group Captain ‘Willie’ Williams (the security officer) and a few senior civil servants. Everyone passing through the front door could be monitored. The garden gate was used only by key holders and, to save manpower, was monitored electronically.

Mr Heath’s piano was, as I understood it, finally removed on a precision-operated cherry picker. Just before my time, as it was, this was not my problem. But Mr Wilson was another matter. At first, he was resident in a leased town house in Lord North Street which, although outside the immediate range of the private secretaries, seemed to him nicely within either walking or driving distance of No 10. With radio contact we could ensure that uniformed officers were aware of the prime minister’s approach either to Lord North Street or No 10, and they would clear the frontage of members of the public and create space to unload the PM and U-turn and park the official limo. There was no guarantee that the press would not intervene and paparazzi trample upon the innocent. For close security it was vital for us to have control over events and quickly to be able to recognise something or someone unusual.

Departure from No 10 was technically easier but was usually handicapped by indecision from the top. In Churchill’s later days, when he was well past his best but still the people’s choice, he was steered from Private Office – which notified the front door staff that he was on his way – along a line of custodians. The first produced and set his homburg in place, a second slipped him into a warm coat, the next popped a ready-cut cigar in his mouth, and the last one lit it for him just as the front door was opened. Abracadabra, there he was puffing purposefully away as he appeared and gave the ‘V’ sign to the crowd.

Harold Wilson was not in his dotage but did tend to change his mind at the last moment, and this reflected its way down the corridor, and often back again. If he thought about not leaving but staying, the chain of assistants had to follow suit and unwind too – the housekeeper, custodians, policemen and the doorkeeper, not to mention the driver and Special Branch officer who actioned themselves after a helpful nod from Private Office were then as quickly stood down again as departure was postponed. Or cancelled altogether.

As the prime minister often liked to work from his office in the House of Commons, but eat at No 10, then vote in the House before returning for drinks, departures created a certain mayhem which tended, on days with an otherwise undemanding programme, to come to an end at around 10.15 p.m. – after which the PM was driven to the House for the final call to the division lobby. Only after this and any other appointments in his diary might he head for Lord North Street. The call upon police resources was inordinate and demanded co-ordinated dedication.

And so there was much to be said for his residence in No 10 itself, and many a prayer was answered when, in the summer of 1974, he and Mrs Wilson decided to move in and also to respond positively to the beckoning finger from Chequers.

Before Harold Wilson relocated into No 10, the Special Branch day might start at Lord North Street, where the prime minister’s faithful driver, Bill Housden, would already be waiting with the official Rover limo. Bill was usually indoors. As Harold’s personal friend – he was a loyal member of the Labour Party and they were on first-name terms, a liberty we never presumed for ourselves – Bill had routine chores to complete before the PM’s day could start.

To begin with, every daily newspaper had to be collected from the press office at No 10 and delivered inside Lord North Street in time for the prime minister to scan. The PM devoured, and concerned himself greatly with the contents which often, perhaps usually, motivated his mood for the day. With some reason, he was obsessed with the notion that the press were conspiring against him; it was not unknown for him to plan a meeting with Lord Goodman and authorise action for libel or defamation of character. He was usually dissuaded by sober counsel. With the papers in place, Bill’s next task was to play a vital role in the PR department – Mr Wilson’s pipe-smoking public relations’ image. The favourite pipe and a first reserve were reamed and cleaned and filled ready for action. So were the lighter and a spare, with flints carefully checked. A tobacco pouch was filled with Harold Wilson’s favoured weed, together with another spare. A box of matches was laid out as a final resort if the lighters failed. At some early stage in his political career, PR men had advised the importance to the electorate of a dependable, avuncular image, and the associated significance of a middle class, pipe-smoking silhouette.

The paradox was that a pipe was never Harold Wilson’s preference. He was very much a cigar man.

The whole ensemble was then stuffed into the prime minister’s jacket pockets, giving him visibly Bunteresque contours around the lower central area. It was certain that the first task of the duty press officer – hopefully female – would be to remove these lumps, streamline the image and brush him down if a television appearance was on the agenda.

The work of the day started soon after arrival in No 10 with an informal gathering of the ‘Kitchen Cabinet’, as the press corps had dubbed it, held within screaming distance of Private Office in a room occupied by his political secretary Marcia Williams (later Baroness Falkender). Participants included Marcia and her aide, trade unionist Albert Murray (later Lord Murray); press secretary Joe Haines (still Joe Haines); Bernard Donoughue (now Lord Donoughue), head of the policy unit; Bill Housden; the PPS; and the prime minister. If the newspapers had not ruined the start to a prime ministerial day, the Kitchen Cabinet was sure to do so. It also provided entertainment for the ground floor staff. Keeping or reading minutes was not on the agenda.

Invariably, a noisy hysteria would be generated. Within an unfortunate radius, this could hardly be avoided. The men tried to remain implacable but some, volatile characters as they were, could be guaranteed to retaliate to provocation. The prime minister was champion in the Imperturbable League.

It seemed a strange way to run the country.

TWO

He [Bill Housden] wants an OBE or CBE so that he can take his wife to the Palace.

Downing Street Diary, by Bernard Donoughue, Volume Two, p. 699

Having arrived at an understanding with Lord (‘Tom’) Bridges, it was time to meet other important persons of influence within No 10. ‘You can call me Bill,’ said Bill Housden, the Prime Minister’s number one driver. At the time of Harold Wilson’s resignation in 1976, he told me that he deserved a knighthood to go with his existing MBE. He was not joking.

All this was unique in the annals of the Government Car Service, of which Bill was an ordinary member. But having joined the Labour Party and made himself valuable to Harold Wilson for many years, Bill could rightly claim to be the prime minister’s personal friend. It was never obvious how Mrs Wilson placed herself in this relationship, but it was apparent that she did not always see the necessity of becoming a close family friend, whereas Harold (and Bill was the only one of the full-time Downing Street staff on first-name terms) was godfather to Bill’s children. In turn, Bill supplied saucy magazines for relaxing weekends at Chequers and updates on the football First Division. This dedication was sometimes rewarded with an incongruous appointment as the PM’s ‘valet’ when he fancied official travel abroad. It is fair to say that this did not always meet with the unqualified approval of the organising civil servants; the extra travel and accommodation costs were difficult to hide and Bill was sometimes recast in a more likely role as official baggage master for the whole delegation.

His trusted relationship with the prime minister meant that Bill was not universally popular, in spite of the authority he wielded as a full member of the Kitchen Cabinet, but he was clever enough to handle the senior civil servants with appropriate respect. Most of the insiders grew to accept Bill but, knowing about his daily contacts with both the PM and Marcia, he was never fully trusted. The position of the appointed number one driver with the three regulars in the drivers’ room is always difficult, and although he was the key figure he tried never to patronise his colleagues. In spite of the fact that he knew they voted Conservative he joined in the card school, did his share in the tea club and used his influence with ‘the Boss’, who permitted them to work without wearing the dreaded official caps which had always been mandatory. From the detectives’ point of view he was a critical link – not least because he was the Kitchen Cabinet go-between with the usually phlegmatic Harold and the highly volatile Marcia Williams.

One of the most important routines for everyone working inside Downing Street, and having a need to know, is the distribution of the prime minister’s daily diary. This is delivered by hand to each relevant office as early in the preceding afternoon as possible. It is the final guideline on how the staff, as well as the prime minister himself, will need to plan their day. It is, of course, highly confidential. The final version is the product of a year of preparation. A provisional draft goes round twelve months in advance; it is then updated quarterly, monthly, weekly, and, finally, daily.

During Mr Wilson’s time, input came to the appointments desk through Private Office. The sources were the prime minister himself and sometimes his family, his constituency and the party, political advisers in Downing Street, the security services, Buckingham Palace, the Cabinet and Cabinet Office, the diplomatic service, the press office and Whitehall departments. Yes, and Bill Housden as well. This was all collated, shuffled, considered, put to committees and passed before the prime minister for provisional approval. The final product was prepared by the secretariat in the Garden Rooms.

From the diary, recipients got to work to make the programme run smoothly. The Garden Room allocated secretaries for any event outside No 10 and prepared travel arrangements with the RAF or British Rail. They were also responsible for accommodation reservations. The travel agents in the Palace of Westminster were often involved because transport for the support staff had to be phased in. Private Office allocated a duty clerk and private secretary. Drivers worked out their roster, recommended routes and calculated timings and notified Private Office. The detectives co-ordinated their duties, helped plan the route navigation and started telephoning district chiefs of police in London and chief constables elsewhere. If travel abroad was involved they might also activate their own contacts or ask embassies and high commissions to do so. One detective would usually be posted to any advance party travelling ahead for the prime minister’s visits out of town or abroad. He would co-ordinate security and communications in tandem with all the authorities involved. The very fact that political leaders demanded the right to vary the programme in reaction to developments separated No 10 planning from royal visits, which called for meticulous but inflexible detail. Prime ministers invariably needed imaginative pre-emptive alternatives.

For travel out of town or abroad, security depended upon efficient and positive management of local agencies by the allocated No 10 Special Branch officer. Experience counted a great deal here, as he would often be technically junior in certain pecking orders. Firearms protocol also had to be dealt with. Where the allegedly agreed plan was for local officers to provide the final line of personal protection, our own firearms were not mandatory. We generally conspired to take them anyway – whether strictly legally or not. In Canada, where the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) were supremely efficient and authoritative, this was not a problem and we left our guns behind. The RCMP did the same when they came to the UK.

For foreign VIP visitors to London, Scotland Yard insisted that personal protection was carried out exclusively by Special Branch, which had total control over, and responsibility for, their security. This sometimes put us at a disadvantage when our prime minister travelled abroad and reciprocation was insisted upon. It was particularly difficult in Third World, unstable countries where the risk was great and the capacity of the local police was minimal and sometimes undisciplined. Considerable diplomacy – or sleight of hand – was called for. If uncovered, our own last-ditch tactics might be copied by the wild and traditionally trigger-happy men, sometimes posturing as protection officers attached to undemocratic dictators when they came to London.

Very occasionally all this planning went smoothly. More often, last-minute changes at the top unravelled much of it, demanding cancellations and frenetic re-planning, because the preference is that British prime ministerial visits should be both dignified and secure. Our own minimum requirement was to be kept fully updated as the programme developed and redeveloped, so that we could take pre-emptive measures for every contingency. We could then, for example, focus our physical presence around unscheduled disturbances or hitches representing potential danger.

Under most circumstances, our small unit could provide no more than three men to manage any operation, leaving one office manager in London. This called for synchronised thinking and action and we worked to a policy of equality, although the final buck stopped with me. After a few months, rank was disregarded and we announced ourselves as Mr So-and-So from Scotland Yard. In some foreign countries and in areas controlled by our own armed forces, prestige was important and not to be undermined if a perfectly competent officer announced himself to be a detective sergeant. This could lead to instant banishment below stairs and commensurate lack of authority. Although the main thrust was to ensure operational effectiveness, this policy turned out to have an additional bonus.

Our embassies and high commissions abroad were often unaware that the world had changed elsewhere and that Victoria was no longer Queen of the Empire and Empress of India. Politicians were usually despised as upstart social inferiors, while policemen were regarded as Bow Street Runners. If we failed to exert our authority in this outdated environment, we might also fail to assemble enough local support to protect the prime minister adequately. I later found that the Conservative Margaret Thatcher was no better treated than Labour prime ministers. When dealing with a Mr So-and-So, as opposed to Sergeant, members of the diplomatic service were reluctant to leave themselves vulnerable by underrating our authority and in general the outcome was for us all to be given adequate status and commensurate help.

It was clear to my colleagues that once within the ‘abroad’ mode they were free to promote themselves on the spot if a clear definition of their rank became unavoidable.

The focus of all this was the diary. And it was here that Bill Housden was so useful. He not only took direct instruction along to Private Office, he was also able to give broad hints of guidelines such as: ‘It seems likely that Mrs Wilson will insist that they go to the Scillys before Easter.’ As a tipster, such advance knowledge was of the greatest importance to those fitting together the prime minister’s programme. It was even more so for us because, during the many hours we had to spend together, Bill would go a lot further. He was a nimble-minded middle-man. Once trust in our discretion was established the information he supplied enabled us to keep ahead of the many internal complexities within No 10, to keep operationally on the ball and to be alert for the appearance of thunder clouds.

It was important to watch him for the occasional, calculated deception – sometimes to test that we were still leak proof and sometimes, with instructions from a higher authority, to deliberately mislead. It was all an intensely political, real-life mixture of pass-the-parcel and Russian roulette.

In return, Bill became dependent upon our unit for many favours, for we often had influence where he had none.

Nobody was in doubt about the strength of the relationship between Bill Housden and the prime minister. For a time, however, where he stood with Marcia Williams was less than clear. Having consulted Mr Wilson after her elevation to the peerage as Baroness Falkender in mid 1974, the detectives knew her as Mrs Williams, although she was now divorced. Betty and Tony Field, her sister and brother, had associations with No 10, but the family name was never used in Marcia’s case. For anyone not in close and regular touch with her, or a personal friend, it was difficult to know how to address Mrs Williams after she became an amalgam of both left-wing Transport House credo and the ultra-conventional House of Lords.

Uniquely, Bill spoke of her as ‘Marcia’.

However, warning signals from the Kitchen Cabinet grew in volume and, we noted, increasing confidences from Bill. In spite of the power vested in his special relationship with Harold Wilson, both Bill and Albert Murray, Mrs Williams’ assistant in the Political Office, were very much under her control and domination. Ample evidence exists of the commitment the prime minister felt toward her from early days in his political career. With just average secretarial aptitude she secured a position of supreme significance in his blossoming career. She was politically astute, had a sparkling and penetrating wit and useful left-wing insight into the character of others prominent in the Labour Party. On a few occasions before he became prime minister, she travelled abroad with Mr Wilson officially and, among the many conspiracy theories which proliferated around their relationship, was the allegation that they were Soviet agents on the one hand and in the midst of an affair on the other. Contradictory stories also circulated that she had been the key figure in his rise to power. These rumours – and never having been proved, they were little better than that – have been impossible to dismiss, even to this day. It is well established in the public domain that, in all probability, a misguided and unaccountable plan to counter communist penetration at the very top of the governmental tree, led individual officers in MI5 (the Security Service) to convince themselves that she was working for the Soviet Union. With guesswork as their only authority, a group then quietly orchestrated smears against her and the prime minister.

As Harold Wilson’s concerns about the media and the Secret Services later matured into near paranoia, I was more than once dragged into events too.

Bill’s commitment to Marcia Williams, although not of the same order as that to his boss, was in his own terms no less important. He was unhappy – even after the prime minister’s understanding and authority – on days when the official limousine was left at her disposal for morning shopping in the West End. The PM’s name was used to ignore parking restrictions. Both Bill and Mr Wilson skated along thin ice when the limo, driven by Bill, was sometimes made available for her social evenings too. With no security risk to the prime minister as justification, how the usual discipline relating to private use of car and driver was covered by Private Office is not known. However, although a great deal of latitude is accorded to prime ministers, it can be taken as a strong likelihood that careers may have been jeopardised. Is it remotely possible that Mrs Williams compensated the Treasury herself?

The dam came near to collapse in January 1975 when Bill walked out on her for constantly attacking him. He thought it must have been because she was jealous of his relationship with Mr Wilson. He also told policy adviser Bernard Donoughue that her style of life needed £20,000 a year and that ‘she throws her money around in the shops so much that I sometimes get frightened’. As Bernard’s declared income at the time was £8,000 a year, it was unlikely that she got any sympathy from him.