10,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Parkstone International

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

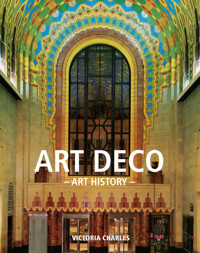

Art Deco style was established on the ashes of a disappeared world, the one from before the First World War, and on the foundation stone of a world yet to become, opened to the most undisclosed promises. Forgetting herself in the whirl of Jazz Age and the euphoria of the “Années Folles”, the Garçonne with her linear shape reflects the architectural style of Art Deco: to the rounded curves succeed the simple and plain androgynous straight line… Architecture, painting, furniture and sculpture, dissected by the author, proclaim the druthers for sharp lines and broken angles. Although ephemeral, this movement keeps on influencing contemporary design.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 226

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Author:

Victoria Charles

Layout:

Baseline Co. Ltd

61A-63A Vo Van Tan Street

4th Floor

District 3, Ho Chi Minh City

Vietnam

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Charles, Victoria.

Art deco / Victoria Charles.

pages cm

Includes index.

1. Art deco. I. Title.

N6494.A7C49 2013

709.04’012--dc23

2012051017

© Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

© Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

Image-Barwww.image-bar.com

© Edgar Brandt, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris (pp. 14, 89, 116)

© Cl. Romilly Locker / Getty Images / The Image Bank

© Cartier

© Jean Dunand, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris (pp. 95, 132, 156, 157)

© Carl Milles, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / BUS, Stockholm

© Raoul Dufy, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

© Jean Goulden, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

© Albert Gleizes, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

© Paul Colin, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

© André Groult, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

© Jean Lambert-Rucki, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

© René Lalique, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers, artists, heirs or estates. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 978-1-78310-391-1

Victoria Charles

CONTENTS

Introduction

Exhibition programme

Architecture, Painted and Sculpted Decor

“Modern” architecture: new materials, new shapes

The French section

Foreign sections

Austria

Belgium

Denmark

Spain

Great Britain

Greece

Italy

Japan

The Netherlands

Poland

Sweden

Czechoslovakia

Russia

Furniture and Furniture Sets

Contemporary developments and trends

French section

Presentation of the French section

Ordinary home furnishings

Provincial participation

Colonial art

Foreign sections

Austria

Belgium

Denmark

Spain

Great Britain

Italy

Japan

The Netherlands

Poland

Sweden

Czechoslovakia

Robert Bonfils, Poster for theExposition de Paris (Paris Exhibition) of 1925.

Colour woodcut. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Introduction

Decorative and industrial arts, like all forms of art, are an expression of life itself: they evolve with the times and with moral or material demands to which they must respond. Their agenda and means are modern, ever-changing, and aided by technological progress. It is the agenda that determines the shapes; hence technology is also part of it: sometimes they are limited by its imperfections, sometimes it develops them by way of its resources, and sometimes they form themselves. Weaving was initially invented because of the need to clothe the body. Its development has been crucial to that of textile arts. Today, market competition has created the need for advertising: the poster is a resulting development and the chromolithograph turned it into an art form. Railways could not have existed without the progress of metallurgy, which in turn paved the way for a new style of architecture.

There is a clear parallel between human needs and the technology that caters to them. Art is no different. The shapes it creates are determined by those needs and new technologies; hence, they can only be modern. The more logical they are, the more likely they are to be beautiful. If art wants to assume eccentric shapes for no reason, it will be nothing more than a fad because there is no meaning behind it. Sources of inspiration alone do not constitute modernism. However numerous they are, there is not an inexhaustive supply of them: it is not the first time that artists have dared to use geometry, nor is it the first time that they have drawn inspiration from the vegetable kingdom. Roman goldsmiths, sculptors from the reign of Louis XIV, and Japanese embroiderers all perhaps reproduced the flower motif more accurately than in 1900. Some “modern” pottery works are similar to the primitive works of the Chinese or the Greeks. Perhaps it is not paradoxical to claim that the new forms of decoration are only ancient forms long gone from our collective memory.

An overactive imagination, an over-use of complicated curves, and excessive use of the vegetable motif – these have been, over the centuries, the criticisms ascribed to the fantasies of their predecessors by restorers of straight lines, lines that Eugène Delacroix qualified as monstrous to his romantic vision. What’s more, in the same way that there has always been a right wing and a left wing in every political spectrum, ancient and modern artists (in age and artistic tendencies) have always existed side-by-side. Their squabbles seem so much more futile, as with a little hindsight, we can see the similarities in the themes of their creations, which define their styles.

The style of an era is marked on all works that are attributed to it, and an artist’s individualism does not exempt his works from it. It would be excessive to say that art must be limited to current visions in order to be modern. It is, however, also true that the representation of contemporary customs and fashion was, at all times, one of the elements of modernism. The style of a Corinthian crater comes from its shape, a thin-walled pottery vessel inspired by the custom of mixing water and wine before serving them. But its style also results from its decoration: the scenes painted on it depicted contemporary life or mythological scenes.

Jean Fouquet, Pendant, c. 1930.

White gold, yellow gold, and citrine, 8x7cm.

Private collection, Paris.

Those who think that the Jacquard loom, the lace-making machine, the great metalworking industry, and gas lighting all date from the beginning of the 19th century, would be interested to learn that they were not pioneering technologies; they were only used to copy ancient silks, needle-points, or spindle laces to create imitation stone walls and light porcelain candles. Hence, it is necessary to admire those who dared to use cast and rolled iron in construction. They were the first to revive the tradition of modernism in architecture; they are the true descendants of French cathedral builders. Therefore, Antoine-Rémy Polonceau, Henri Labrouste, and Gustave Eiffel are perhaps the fathers of the 19th-century Renaissance, rather than the charming decorators who, following John Ruskin, tried to break with the pastiche and create, first and foremost, a new style using nature as a starting point.

The vision of nature, literally paraphrased and translated in the works of Émile Gallé, was not compatible with the demands of the design and the material. “A marrow,” wrote Robert de Sizeranne, “can become a library; a thistle, an office; a water lily, a ballroom. A sideboard is a synthesis; a curtain tassle, an analysis; a pair of tweezers, a symbol.” The research of something new borrowed from the poetry of nature, in breaking voluntarily with the laws of construction and past traditions, must have offended both common sense and good taste. To transpose nature into its fantasies rather than studying its laws was a mistake as grave as imitating past styles without trying to understand what they applied to. This was just the fashion of the time, but being fashionable does not constitute modernism.

Reviving tradition in all its logic, but finding a new expression in the purpose of the objects and in the technical means to achieve them, which is neither in contradiction nor an imitation of former shapes, but which follows on naturally; this was the “modern” ideal of the 20th century. This ideal was subject to a new influence: science. How could it be that artists would remain oblivious to the latent, familiar, and universal presence of this neo-mechanisation, this vehicle for exchanges between men: steamers, engines, and planes, which ensure the domination of the continents and the seas, antennas and receivers which capture the human voice across the surface of the globe, cables which mark out roads awakened to a new life, visions of the whole world projected at high speed on cinema screens? Machines have renewed all forms of work: forests of cylinders, networks of drains, regular movements of engines. How could all this confused boiling of universal life not affect the brains of the decorators?

Edward Steichen,Art Deco Clothing Design, photograph taken at the apartment of Nina Price, 1925.

Gelatin silver print.

Boucheron (jewellers), Decorative brooch, 1925.

Lapis lazuli, coral, jade, and onyx set in lead

glass and gold, with a turquoise, diamond,

and platinum pendant. Boucheron SAS, Paris.

Pierre Chareau, Pair of lamps ‘LP998’, c. 1930-1932.

Alabaster, height: 25cm.

Private collection.

Exhibition programme

Thus, from all sides, it was an era metamorphosed by scientific progress and economic evolution, turned upside down politically and socially by the war, liberated from both anachronistic pastiche and illogical imaginings. Whilst the artist’s invention reclaimed its rightful place, machines, no longer a factor in intellectual decline through its making or distributing of counterfeit copies of beautiful materials, would permeate aesthetically original and rational creations everywhere. This world movement, however, was lacking the effective support and clear understanding of the public. Only these accolades would merit an exhibition. But rather than a bazaar intended to show the power of the respective production of the nations, it would have to be a presentation of excellence turned towards the future.

When the Exposition internationale des Arts décoratifs et industriels modernes, or International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts – originally planned for 1916, but adjourned because of the war – was re-envisaged in 1919 by public authorities, modifications were imperative. The 1911 classification project contains only three groups: architecture, furniture, and finery. The arts of the theatre, of the streets, and the gardens, which were special sections, naturally required a new group. In its title, the new project also comprised a significant addition. The Exhibition was to be devoted to decorative and “industrial” arts; it would affirm the willingness of a close co-operation between aesthetic creation and its distribution through the powerful means of industry. Besides the manufacturers, the material suppliers were also to be given a large space, thanks to the design which inspired the presentations of 1925. “Modern” decorative art was to be presented in its entirety like an existing reality, completely suited to contemporary aesthetic and material needs. Ceramic tiles, hanging fabric wall coverings, and wallpaper – each has their reason for adorning particular spaces. The ideal mode of presentation was thus the meeting of a certain number of “modern” buildings, decorated entirely inside and out, which would be placed next to stores, post offices, and school rooms, constituting a kind of miniature city or village.

Moreover, these designs had to inspire the materials they had to work with, adopted for the use of the location granted and the distribution of the works which were thoughtfully placed in their midst. That is how four principal modes of presentation were determined: in isolated pavilions, in shops, in galleries of the Esplanade des Invalides, and in the halls of the Grand Palais. The isolated pavilions, reserved for associations of artists, craftsmen, and manufacturers had to represent village and countryside homes, hotel businesses, schools, and even churches and town halls. In short, all the framework of contemporary life could be found here. Shops marked the importance attached to urban art and offered the possibility of presenting window-dressings, as well as displays, spanning one or more units. The galleries, particularly for architecture and furniture, allowed compositions connected to the Court of Trades, which were managed by the theatre and the library. They were meant to constitute the largest part of the Exhibition. At last, the interior installations of the Grand Palais were systematically categorised.

The Exhibition aroused new activity long in advance, as a consequence of the emulation it caused among artists and manufacturers. The creator’s efforts were significantly encouraged by groups of “modern” minds, which grew in number and made engaging and effective propaganda. Foreign exhibitors attach no less importance than the hosts to an opportunity that would allow most countries to compare their efforts and enrich their designs. Thus, the frame of mind of the exhibition was not a centralising narrow-mindedness, a formal modernism of the time. Far from imposing rigid and concrete specifications of style, the Exhibition of 1925 became apparent as an overview intended to reveal the tendencies in contemporary art, and to showcase their first achievements. The only stipulation was for it to be an ‘original production’, appropriate to the needs, universal or local, of the time. This phrase could be used to refer to any previous century, which may have only been said to be great because it was thought to be innovatory.

Donald Deskey, Folding screen, c. 1930.

Wood, fabric, painted and metal decoration.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Edgar Brandt, Oasis, folding screen (detail), c. 1924.

Iron and copper.Private collection, Paris.

Architecture, Painted and Sculpted Decor

All exhibitions comprised of new construction greatly credited the efforts of the architects: well-adapted to the requirements for its brief, more or less accessible and expressive, and leaving visitors with a sincere and lasting first impression. Even more so, in an exhibition devoted to decorative and industrial modern arts, architecture required the most attentive care and excited great interest. Indeed, the most utilitarian of all arts is also the most “decorative” and the most closely related to industrial progress.

Decorative art is as such based on the great number of its creations. Large silhouettes of buildings are more important in the scenery of life than all other objects with which we can adorn it. Sculpture and painting can only add a little to the beauty of their already thick volumes, and will not be able to enrich their legacy, should they not have their own intrinsic nobility. As for the alliance of art with industry, architects did not wait to conclude it, the eloquent manifestos which, for almost a century, have proclaimed the need of it. Continuously in search of new materials, effective and economic construction processes, they benefit from the discoveries of science and sometimes even cause them. Lastly, having to create a framework where everything that further embellishes the pavilion finds its place and makes sense, architecture coordinates the efforts of the other arts. It should, therefore, be a source of inspiration. However, it ultimately becomes a slave to the whole, a mere shell from which a unity of expression must originate in order to create the style of its time or, more simply, the harmony of the pavilion itself.

“Modern” architecture: new materials, new shapes

If we understand by “modern” architecture that which profits from the successes of industry, by using the new materials and methods of construction of the time, in order to carry out their new programmes, then the Exhibition of 1900 truly marked the decline of “modernism”. In France, the 19th century, in spite of its taste for formulas borrowed from previous eras, was marked by strong and original works. Progress in metallurgy, a consequence of the development of public transport infrastructure, had drawn attention to the varied possibilities and real beauty of iron. From Henri Labrouste to Victor Baltard, and Paul Sédille to Émile André, architects used it unreservedly for the construction of public libraries, market halls, stations, department stores, and museums. With the Eiffel Tower, the Machine Gallery, and the palaces of Jean-Camille Formigé, the Exhibition of 1889 dedicated a lengthy and persevering effort to the cause. Nevertheless, eleven years later, despite a few exceptions, the retrograde tendencies dominated.

William van Alen, Chrysler Building, entrance hall, 1927-1930. New York.

Is it necessary to recall to which point the multiple implementations of science, steam, hydraulic force, electricity, and the reciprocating engine modified the conditions of life? Must we discuss the progress of transport systems, the development of industrial and commercial enterprises, the evolution of social ideas, or how health concerns altered the way everything was viewed? By observing these causes one by one, we would find the origin of buildings whose modest beginnings aroused the admiration of previous generations and which were, in comparison, quite varied from the boldest expectations of a hundred years ago: stations, hotels, factories, department stores, housing estates, schools, public swimming pools – so many projects which, despite the many years of stagnation due to war, stimulated the imagination of architects in every country.

The layout, structure, and façade of antique houses had changed; there is nothing better than a house to reveal the customs of a country and a time period. A typical house of the 1920s has various floors, distributed between tenants or landlords, of the space. The interior distribution most clearly reflected everyone’s new needs. Using thicker walls, the architect was able to provide a whole system of ducts and piping for smoke, water, gas, electricity, and steam, a vacuum system to ensure that the “rented box” became, according a very visual word, a “dwelling machine”. In the early 20th century, in all the relatively opulent buildings, the narrow old vestibule evolved into a spacious gallery, an example first exhibited by Charles Garnier. Toilets and bathrooms got bigger, often at the expense of the bedroom or the nearly obsolete living room. The dining-room and living rooms co-habit, separated by a half-wall, though still considered to be only one room. Where necessary, the number of rooms would be reduced in order to obtain, on an equal surface, some larger areas with better ventilation. Bold theorist of new architecture, Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, better known as Le Corbusier, offers the following advice in his Manual of the Dwelling:

Demand that the bathroom, fully sunlit, be one of the largest rooms in the apartment, the old living room for example. With full-length windows, opening, if possible, onto a terrace for sunbathing, a porcelain washbasin, a bath-tub, showers, and gym equipment. In the adjacent room: a walk-in wardrobe for dressing and undressing. Do not undress in your bedroom. It is not very clean and it creates a distressing disorder. Demand one big room in place of all the living rooms. If you can, put the kitchen under the roof, to avoid odours. Demand a garage for cars, bicycles, and motorbikes from your owner, one per apartment. Ask for the servants’ quarters to be on the same floor. Do not pen your servants in under the roofs.

One should note that the writer of this catechism would prefer bare walls and replaces the cumbersome pieces of furniture commonly exposed to dust with wall cupboards or built-in closets. Our need for outside air and light translates in the number, shape, and dimension of bay windows, using bow- and oriel windows which increase brightness, available surface area, and also allow for enfilade views, such as those seen from old watch towers. Fake decorated plating on giant pilasters are no longer of fashion, instead, a careful study of the interior distribution of space and the height of the ceilings, so as more modern architects can seek to unite the entire construction and give life to its façade. As early as 1912, Henri Sauvage found another very original solution: a tiered house in which no floor deprives the lower floors of air or light, where each inhabitant is at home, on his terrace which may be full of shrubs and flowers.

Heinsbergen Decorating Company, Two designs for decorative panels for the Pantages Theater, c. 1929.

Watercolour on paper.Upper part of the

border above the fireproof curtain of the apron.

Heinsbergen Decorating Company, Project for the ceiling of the Pantages Theater, c. 1929.

Watercolour on paper.

Anton Skislewicz, Plymouth Hotel, 1940. Miami Beach.

Individual homes of cheaper construction are better suited for new experiments than large constructions built for rental purposes. At this time, one could easily have believed that because of the high price of building sites in the cities and because of the housing-shortage crisis, private mansions, enclosed between houses that rise to any height, would gradually disappear. But the periphery, or the suburbs, of large cities, remains an option; cars brought inhabitants closer to the centre. The housing shortage, a consequence of the interruption of construction caused by the war, and the temporary uncertainty of the value of money determined the revival and even proliferation around major urban centres; apart from the private mansion, the word would often be considered pretentious, at least referring to the small, family house. Here, a few young architects, such as Robert Mallet-Stevens, André Lurçat, Jean-Charles Moreux, and Henri Pacon, applied, with an intransigence which often does not exclude taste, their principles of rational distribution and construction. Thanks to bay windows that span the length of a room, obscure angles are avoided. Although they banished all decoration, they were concerned about practical details which were carefully studied: interior blinds, sliding doors and windows, saving space by not having to install cumbersome shutters. Uncluttered rooms, for them, meant supreme elegance.

To carry out these various projects, from large factories to small houses, the architect takes advantage of the industry’s achievements. Materials are provided to him cheaply due to more time efficient working methods. The invaluable invention of plywood, which – unlike natural wood – does not warp over large areas, offered new facilities for the execution of panelling and doors. Rolled steel, the newest innovation to come out of factories, was more lightweight and resistant than its predecessors; they are invaluable to the halls of department stores and openwork façades of commercial buildings. They are also used in houses for window joinery; metal allows more light to stream through than wood. However, iron has well-known defects. For example, it oxidises if it is not protected by a coating and it requires constant monitoring, which can be expensive to maintain. One would agree with Auguste Perret when he said: “If man were to suddenly disappear, the steel and iron buildings would not be long in following them.”

Fortuitously invented in 1849 by Joseph Monnier, a gardener of Boulogne, improved by the research of Joseph-Louis Lambot, cement or reinforced concrete consists of a mixture of cement, sand, and stones coating a steel reinforcement. The stones then act as a part of the inert material, like grease-remover mixed with earth in large ceramic containers. The relationship between the ratio of steel expansion and cement allows the concrete to lengthen while following the deformations of metal without falling apart, so that, in essence, the reinforced concrete behaves like a single entity. Reinforced concrete is well-suited for finer work. Cement hardens quickly, but it is breakable, making it better to use for posts and beams rather than hollow blocks because the works can be altered after a few days. The speed of its creation is comparable in speed to the assembly of iron frames which were prepared in advance with expensive machinery. Concrete made with clinker is less resistant to the pickaxe than granular cement and, hence, invaluable to temporary buildings. Used for roofs, floors, and partitions due to its light weight, it protects against heat and cold and often decreases the excessive resonance which comes with reinforced concrete constructions. The strengthened stone is a mixture of many materials, which makes it suitable for façade renovation. Whatever its varieties, this resistant material allows the fast construction of a structure in which the use of other materials might make the project more difficult and ultimately destroy it. A work thus built is an artificial monolith. It has justly been compared to the concrete buildings of Rome and Byzantium, where tensile brick framework played a role analogous to iron and concrete.

The consequences of this discovery, from the point of view of construction, can well be seen: extraordinarily long lintels, long-ranging, continuous arcs made from a single piece, and strong and slender posts. The obstruction of the fulcrums is kept to a minimum much more easily than in Gothic constructions. Whilst the intersecting ribs required buttresses and flying buttresses to balance it out, the monolithic framework in reinforced concrete holds without external stays. The walls which do not support any weight but are mere partition walls, can be removed on the whim of the architect. He can replace a solid wall with a double wall to lock in an insulating air pocket. Engineers were the first to understand the part reinforced concrete could play in architecture. Anatole de Baudot, who had already preached its virtues through his teachings, employed it at the end of the 19th century at the Lycée Lakanal and the Church of Saint-Jean-de-Montmartre. He was only in the wrong to abuse narrow curves, whereas his technique was particularly suitable for rectilinear forms. Immediately after him, Charles Génuys gave reinforced concrete an increasingly important standing, in 1892 and 1898, in the factories of Armentières and Boulogne-on-Seine, in 1907, in a private mansion in Auteuil, and afterwards in his constructions for the national railway. Louis Bonnier, who implemented it in 1911 for the lintels, floors, and staircases of the school complex of the rue de Grenelle, reserving brickwork for the façades, made use of it on a large scale in 1922 and 1923 in the great nave of the swimming pool built at Butte-aux-Cailles. At the same time, Charles Plumet made the judicious choice to use it for the new metro stations. Tony Garnier who, already dreaming of reinforced concrete in the shade of the Villa Medici, was able to construct some of his grandest designs out of this material, as part of the major works of the town of Lyon. The terraces of the Lycée Jules Ferry, designed by Pacquet, are made of reinforced concrete, as are the arcs of the departure hall of Biarritz railway station by Dervaux, the cupola of the Boucherie Economique by Alfred Agache, the large roofs of the Galleries Lafayette by Chanut, and the pillars and the vaults of the Church of Saint-Dominique by Gaudibert. Savage used it for the framework of his house with tiered steps from the rue de Vavin and in a building on the Boulevard Raspail; Boileau, in the two basements of new the appendix of Le Bon Marché; Danis, in the framework and the staircase of the Pasteur museum in Strasbourg; Bonnemaison, in his rental properties. In the Church of Saint-Louis in Vincennes, Droz and Marrast combined it with grinding stone and brick. Inside the Church of Saint-Leon in Paris, Leon Brunet adorned it with beautifully laid out bricks. At the very moment when the Exhibition opened, Deneux started to produce the amazing framework of Rheims Cathedral consisting of 17,800 elements moulded on-site, then assembled, put up, and fitted together without the help of bolts or metal parts.

Claude Beelman, Eastern Columbia Building, 1930.

Clad in glazed turquoise terracotta tiles

and copper panels. Los Angeles.