9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Parkstone International

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

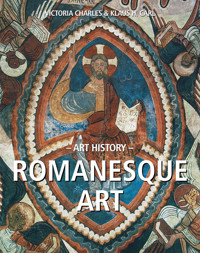

In art history, the term Romanesque art distinguishes the period between the beginning of the 11th and the end of the 12th-century. This era showed a great diversity of regional schools each with their own unique style. In architecture as well as in sculpture, Romanesque art is marked by raw forms. Through its rich iconography and captivating text, this work reclaims the importance of this art which is today often overshadowed by the later Gothic style.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 61

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Victoria Charles and Klaus H. Carl

– ART HISTORY –

ROMANESQUE

© 2024, Confidential Concepts, Worldwide, USA

© 2024, Parkstone Press USA, New York

© Image-Barwww.image-bar.com

All rights reserved. No part of this may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world.

Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 979-8-89405-051-5

Contents

THE ROMANESQUE SYSTEM OF ARCHITECTURE

Art in France and Italy

ROMANESQUE SCULPTURE

Stone Sculpture

The Externsteine

Sculpture in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries

Central Germany

Southern Germany

France

Vézelay

Moissac

Italy

THE ART OF WOODWORKING AND GOLD, SILVER AND BRONZE CASTING

PAINTING

ILLUMINATED MANUSCRIPTS

GLASS PAINTING

MURAL AND PANEL PAINTING

Germany

France

Italy

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Nave, Abbey Saint-Michel-de-Cuxa, Codalet (France), c. 1035.

THE ROMANESQUE SYSTEM OF ARCHITECTURE

Widely spread all over Christian Europe, the Romanesque style was the first independent, self-contained and unified style. It is the art of Europe from approximately 1000 CE to the rise of the Gothic style in the 13th century. Architecture dominated Romanesque art, and all other artistic movements such as painting and sculpture, which often demonstrated dramatic motifs, were subordinated. The Romanesque style is predominantly a certain use of forms, which branches out into different peculiarities. Nonetheless, most Romanesque structures have certain essential features in common, according to which a system of Romanesque architecture can be established.

In England, France, and Germany we see basilicas rising up. That of San Apoilinare Nuovo at Ravenna (504 CE), built by Theodoric, is one of the finest examples of early Romanesque style. The columns are uniform, and are surmounted by a block which represents the ancient architrave, and is sufficient to support the arches. The triforium is adorned with figures, and the remaining space up to the roof is filled with windows which correspond with arches and are separated by figures. The apse, as in the Roman basilica, contains the bishop’s throne, and is surrounded by tiers of seats for the presbytery.

In the year 800 CE, the Frankish King Charles who had for more than twenty years been the actual ruler of Italy as well as of all Frankish lands, returned to his northern capital at Aachen with the title of Emperor. But it was more than the name of Emperor that Charles brought back with him from Italy to his capital in the north: art and culture first find a real home in Teutonic lands through him. The art that he found in Rome and Ravenna he carried home to his imperial city of Aachen. There we see theatres, palaces, aqueducts, Christian basilicas, and baths; his palaces have long since perished, but his court chapel, now the cathedral of Aachen, stands as a lasting memorial of his greatness.

The mosaics which formerly adorned it have perished; but excellent modern imitations have now been put in their place. Of the magnificent palace of Charles little now remains. The coronation hall was decorated with a hundred columns brought from Italy; within were paintings from the history of his life. On the walls of his palaces, historical events from the Old and New Testaments were for the first time arranged side by side. Roman and early Christian art was spread far and wide by the influence of Charles and his successors.

We have to travel far north into Germany, to the northern limit of the mountainous district of Central Europe, the fantastic, precipitous chain of the Hartz, to the quaint old town of Quedlinburg, the cradle and home of the famous Emperor Henry the Fowler. Here he dwelt peacefully in his youth, till, suddenly raised to the imperial throne. While he lay ill, the wild Hungarians advanced their frontier further and further into Germany. With wise self-control, he bought of them a nine years’ peace, to prepare for the struggle. After his great victory had been gained, a period of peace ensued, in which the moral effect of the struggle showed itself in the general development of the country, of which art was one of the most precious fruits.

The Emperor founded churches, abbeys, and convents, in those days the usual centres of higher culture. Then villages grew into walled towns. The middle class — the chief element of national life and liberty in Germany as elsewhere — began to grow up and flourish.

The church of Quedlinburg is of the eleventh century. How much nearer to us than the Aachen Minster does this basilica already appear, even only regarded externally, with its two massive towers with round-arched windows built over the vestibule. Three porticos, also of the round arched form, re-echo in a series of small arches supported by columns the beautiful curve. In the vestibule, there stands instead of the fountain a piscina, from which believers sprinkle themselves, symbolic of inward purification. Below are the minor round arches supported alternately by pillars and columns. The clerestory again repeats them in long galleries of columns.

Instead of the glittering mosaics on the walls, we here see solemn and more natural figures painted on a blue ground. The dignity of the Byzantine style, degenerated into fossilization, is already transfigured by German feeling. The column capitals in solid cube manifest here and there fantastic forms. The cross vault is freer for eye and feeling than the flat — the widened altar-niche gives room for a larger number of priests. Under it, as now common, a sepulchral church for the sarcophagus — in this case that of Henry I. Next to it a relic chest, of ivory, with scenes from the life of Christ, still awkward, but worked with naive pious feeling.

Eastern view of nave, Church of St Cyriacus, Gernrode (Germany), 959-1000.

Western door, Church of St Cyriacus, Gernrode (Germany), 959-1000.

South-East façade, St Michael’s Abbey Church of Hildesheim, Hildesheim (Germany), 1010-1033.

Far more richly adorned is the Cathedral of St. Michael in Hildesheim, with its six picturesque towers. The church dates from the eleventh century, founded by the learned and art-loving Bishop Bernward. Two of the towers surmount the widened cross-shaped choir; two at the entrance, where there is a second cross nave with a choir; two smaller ones on the gable sides of the cross wings. The perspective of the choir is grandly beautiful. On the bronze doors are sixteen reliefs, by Bernward’s own hand, which already show emancipation from Byzantine tutelage. The short figures, it is true, are rather unwieldy, with the upper part of the body standing out. One wing of the door is devoted to the Fall of Man, the other to the Redemption.