9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Parkstone International

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

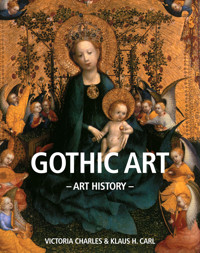

Gothic art finds its roots in the powerful architecture of the cathedrals of northern France. It is a medieval art movement that evolved throughout Europe for more than 200 years. Leaving curved Roman forms behind, the architects started using flying buttresses and pointed arches to open cathedrals to the daylight. A period of great economic and social change, the gothic era also saw the development of a new iconography celebrating the Holy Mary, in contrast to the fearful themes of dark Roman times. Full of rich changes in all the different arts (architecture, sculpture, painting, etc.), Gothic art gave way to the Italian Renaissance and International Gothic.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 63

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Victoria Charles & Klaus H. Carl

GOTHIC ART

© 2024, Confidential Concepts, Worldwide, USA

© 2024, Parkstone Press USA, New York

© Image-Barwww.image-bar.com

All rights reserved. No part of this may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world.

Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 979-8-89405-049-2

Contents

I. Gothic Painting

II. The Altarpieces and The Reliquaries

III. Gothic Painting in Italy

IV. Gothic Painting in Belgium and The Netherlands

V. Gothic Illumination

VI. Gothic Stained Glass Windows

VII. Gothic Sculpture

VIII. Gothic Sculpture in France

IX. Gothic Sculpture in Italy

X. Gothic Architecture

XI. French Architecture

XII. French Expansion

XIII. Gothic Architecture in England

XIV. Gothic Civil Buildings

XV. Gothic Architecture in Germany

XVI. Gothic Architecture in Italy

XVII. The Gothic Churches of Florence and Venice

XVIII. Gothic Architecture in Spain

List of Illustrations

Giotto di Bondone, Madonna and Child Enthroned with Angels and Saints, known as Ognissanti Madonna, c. 1310. Tempera on wood panel, 325 x 204 cm. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence (Italy).

I. Gothic Painting

The Gothic era, originating in France and subsequently spreading across Europe, particularly to Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands, is commonly associated with its distinct architectural style. This period’s intricate and detailed aesthetic, especially notable in the late Gothic phase, is also evident in the caskets designed for relic preservation, which were lavishly adorned by sculptors.

When reflecting on Gothic art, our minds naturally gravitate towards its architectural marvels. However, Gothic creativity extended far beyond architecture, encompassing music, literature, philosophy, and painting. In all these forms, the predominant source of inspiration was deeply rooted in spirituality and the pursuit of the divine. This spiritual inclination was particularly pronounced in painting, where religious themes were almost exclusively depicted. The Romanesque era was characterised by its expansive walls, often adorned with grand frescoes. In contrast, the Gothic period featured smaller wall spaces, leading to a decreased prevalence of such large-scale decorations. Consequently, Gothic paintings tended to be smaller, and in many cases, quite diminutive in size, reflecting the architectural constraints and stylistic preferences of the time.

Hans Memling, The Shrine of St. Ursula, 1489. Oil on panel with gilding, 87 x 33 x 91 cm. Hospitaalmuseum, Bruges (Belgium).

Conrad von Soest, Dortmund Altarpiece: Death of the Virgin (central panel), c. 1420. Oil on wood, 141 x 110 cm. Marienkirche, Dortmund (Germany).

Hans Memling, Triptych of the Last Judgement (central panel), c. 1467-1471. Oil on wood, 242 x 360 cm. Muzeum Narodowe w Gdańsku, Gdańsk (Poland).

II. The Altarpieces and The Reliquaries

During the 14th century, the financial resources to commission art were primarily in the hands of princely courts and the clergy. Consequently, altarpieces, which became increasingly prevalent from the mid-14th century, were predominantly crafted on wooden panels. These altarpieces were designed with functionality in mind, often being foldable. They came in various formats: diptychs with two panels, triptychs with three panels, and the less common polyptych, featuring more than three panels. The sizes of these altarpieces ranged from small, portable designs to grand, imposing structures, typically constructed from wood or ivory.

The emergence of altarpieces was closely linked to the growing fascination with relic shrines, which held significant mystical and religious importance during this period. Initially, relics were housed in simple containers, but over time, these evolved into elaborate structures resembling miniature cathedrals, adorned with noble metals and encrusted with precious stones. In the Gothic era, these shrines were often wooden and featured decorative paintings. A prime example of such craftsmanship is the Shrine of Saint Ursula, created by Hans Memling in 1489. These shrines were typically opened only on religious holidays to display the relics to devotees while remaining closed on ordinary days. The exterior and interior of the shutters were adorned with biblical scenes. Among the most renowned altarpieces is the Triptych of the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, crafted in 1432 by Jan and Hubert van Eyck, a masterpiece that exemplifies the artistic and religious fervour of the era.

While works from this era are often deemed primitive, this perception stems more from their expressive style and representational approach than from a lack of artistic merit in the imagery itself. Many of these pieces might strike viewers as garish or somewhat unrefined, and they are frequently appreciated more for their historical significance than their artistic value. The subject matter typically includes vivid depictions of biblical scenes such as the ‘Last Judgement,’ ‘Purgatory,’ or various martyrdoms, rendered with such realism that they could be mistaken for commonplace events of the period. In an age marked by internal strife, rogue knights, the Inquisition, and the persecution of heretics, the Church heavily relied on this straightforward, albeit stark, visual language. This approach aimed to instil fear in the predominantly illiterate faithful, using these harrowing images as a contrast to the promise of Heavenly Salvation.

Amidst these portrayals of martyrdom and hellish infernos, artists like Hans Memling, Martin Schongauer, and Rogier van der Weyden chose to depict the Virgin Mary with an aura of grace and serenity. This trend, however, shifted during the Renaissance, when painters began focusing less on this aspect of grace and more on the Virgin’s maternal qualities. This shift did not diminish the quality of the artworks but rather influenced their stylistic direction. The works of Hans Memling, Martin Schongauer, and Rogier van der Weyden stand as testaments to the remarkable artistic achievements of the early days of oil painting, making it remarkable that such high levels of artistry were attained during this period.

During this era, secular paintings did not enjoy widespread popularity among artists or patrons. Genres such as still lifes, landscapes, and scenes depicting everyday life were virtually unheard of at the time. Portraiture, while existent, was often limited to pencil sketches. A notable trend of the period was a delightful custom practised by the clergy: they frequently received paintings of biblical scenes as gifts from affluent members of the bourgeois class. These patrons, keen to secure their legacy, often had their own portraits incorporated into these religious scenes. As a result, it was not uncommon to see municipal councillors, mayors, or even wealthy merchants and their spouses, depicted amidst a crowd, captured in a state of devout prayer.

Martin Schongauer, affectionately known as ‘Beau Martin’, stands out as one of the preeminent Gothic painters. He honed his craft in the workshop of his father, Gaspard, a goldsmith based in Augsburg, Germany. Around the age of fifteen, Schongauer enrolled at the University of Leipzig, where he studied from 1465 to 1466. Following his education, he embarked on travels across Europe, including a notable visit to Beaune in Burgundy to study Rogier van der Weyden’s Polyptych of the Last Judgement, a theme that later appeared in one of his own drawings. By 1471, Schongauer had established his own workshop in Colmar. Among his most significant works are The Virgin with a Rose Bush (circa 1473), and both The Adoration of the Shepherds and Portrait of a Virgin, created between 1475 and 1480, distinguished by their light and almost lyrical motifs. His influence extends to his copper engravings, notably impacting Albrecht Dürer. Among these, his Passion of Christ series (1470-1480), consisting of a dozen leaves, and the copper engraving The Adoration of the Magi, completed before 1479, are particularly noteworthy.

Gentile da Fabriano, Adoration of the Magi, 1423. Tempera on panel, 300 x 282 cm. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence (Italy).

Hubert and Jan Van Eyck,