9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

It took Henry VIII twenty-eight years, three wives, and a break with Rome before he secured a legitimate male heir. Yet he already had a son – the illegitimate Henry Fitzroy. Fitzroy was born in 1519 after the King's affair with Elizabeth Blount. He was the only illegitimate offspring ever acknowledged by Henry VIII, and Cardinal Wolsey was even one of his godparents. So just how close did he come to being Henry IX?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

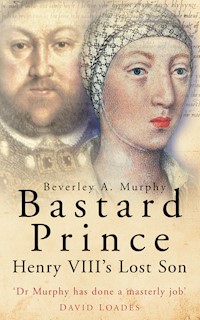

Bastard Prince

Bastard Prince

Henry VIII’s Lost Son

Beverley A. Murphy

Cover illustrations: Portrait of Henry VIII by Hans the Younger Holbein (1497/8–1543), Belvoir Castle Leicestershire/Bridgeman Art Library, London; Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond in 1534/5, by Lucas Hornebolte, The Royal Collection c.2003, Her Majesty the Queen Elizabeth II.

First published in 2001 This edition published in 2010

The History Press The Mill, Brimscombe Port Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QGwww.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved © Beverley Murphy, 2001, 2003, 2004, 2010, 2011

The right of Beverley Murphy, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 6889 1MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 6890 7

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Acknowledgements

Preface

1

Mother of the King’s Son

2

Heir Apparent

3

Sheriff Hutton

4

Lord Lieutenant of Ireland

5

Young Courtier

6

Landed Magnate

7

Legacy

E

PILOGUE

Henry the Ninth

Family Trees

Notes

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor David Loades for encouraging my conviction that Richmond’s life merited further investigation. I am indebted to the British Academy, who funded much of the initial research. In compiling this study I have benefited from the expertise of many friends and colleagues, whose input has enriched the finished work. I am particularly grateful to Dr Alan Dyer, Dr Simon Harris, Dr S.J. Gunn and Dr Hazel Pierce for their contributions. Thanks are also due to all those archives and libraries whose staff and collections have provided invaluable assistance in my search for a true picture of the duke.

Finally, my debt is to those of my friends and family who have had to live with the ghost of a little known Tudor Prince. The many ways in which they have provided support and assistance are especially valued.

Preface

Our Only Bastard Son

The marital misfortunes of Henry VIII are one of the most notorious episodes in English history. Even those with little or no interest in the history of Tudor times can name the king who had six wives. His pursuit of a legitimate son and heir was not the sole factor in the events of the Reformation which shook England and became the scandal of Europe in the sixteenth century. Henry’s desire to father a male child and secure the future of his dynasty cannot be overestimated. Yet it was to take him twenty-eight years and three wives, before Jane Seymour was finally able to present the King of England with his prince.

The events of the preceding years, with Katherine of Aragon as the wronged wife and Anne Boleyn as the other woman, would not seem out of place in a modern soap opera. As such the popular perception of events is often at odds with historical fact. Henry VIII is berated for his repudiation of Katherine on a whim, without any appreciation that the couple lived as man and wife for almost twenty years. Anne Boleyn’s reputation as a whore is not dimmed by the centuries, despite the fact that she was apparently Henry’s ‘mistress’ for five years before she actually had full sexual intercourse with him.

Any mention of the fact that for much of this time Henry VIII had a healthy, promising, albeit inconveniently illegitimate son, generally evokes one of two responses. Either there is the assumption that all monarchs had hordes of illicit offspring, which rendered bastard children insignificant in the broader fabric of political affairs. Or, more commonly, there is a profoundly sceptical enquiry as to the identity of the child.

This is not entirely unreasonable. The existence of the Duke of Richmond was no secret to his contemporaries. However, he has fared rather less well in attracting the attention of historians. The main printed source for his life remains John Gough Nichols’ Inventories published in 1855.1 Richmond has occasionally benefited from the notoriety of other figures at the Tudor court, for example, featuring in the biographies of his childhood friend, Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey. On other occasions his envisaged role in Ireland has stirred some interest. However, even those with a well informed knowledge of Tudor history would be forgiven for thinking there were only three events of note in Richmond’s life. His birth in 1519, his elevation to the peerage in 1525, followed by his death in 1536.

The true picture is rather more complex. In 1525 Henry VIII had been married for sixteen years, with only a nine-year-old daughter to his credit. When his illegitimate son was created Duke of Richmond and Somerset it prompted intense speculation that Henry VIII was intending to name him as his heir. In 1536 that speculation intensified when Anne Boleyn had been able to present the king with nothing more than two miscarriages and yet another daughter. In the meantime, Richmond’s tenure as Lord Lieutenant of the North and his appointment as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland heralded new departures in Tudor local government. His contemporaries believed he would become King of Ireland. Those suggested as possible brides included Catherine de Medici, the future Queen of France. His unprecedented status as the duke of two counties made him the foremost peer of the realm. In almost every way Henry VIII treated him as his legitimate son and in almost every way that is the role Richmond fulfilled.

Since Richmond was only a child, some of the traditional areas of a biography are inevitably lost to us. There can be little examination of his ability as a soldier, nor is it feasible to build up a picture of a personal affinity in the same way that would be expected of an adult magnate. Yet there are compensations. We know far more of Richmond’s childhood than we might have done had circumstances not required his dispatch to Sheriff Hutton. His youth also allows for the reconstruction of his character in a vivid manner which is often difficult for his fellow nobles. At the same time, because Richmond’s activities often encroached on the traditional preserves of the adult world, those areas where one would usually look for traces of an established lord, such as litigation, diplomacy and patronage, are by no means lacking.

Much of Richmond’s importance stems from the fact that while he lived he was the king’s only son. He did not survive to see his fortunes eclipsed by the birth of the legitimate Prince Edward, who was born on 11 October 1537. Indeed, when Richmond died on 23 July 1536, Jane Seymour was not even pregnant. Examples of Henry’s affection for his only living son abound and during the King’s marriage to Katherine of Aragon, Richmond was widely considered to be:

very personable and of great expectation, insomuch that he was thought not only for ability of body but mind to be one of the rarest of his time, for which also he was much cherished by our King, as also because he had no issue male by his Queen, nor perchance expect any.2

There can be no doubt that Richmond was Henry’s son. In his case, the distinctive red hair and wilful Tudor personality were merely secondary considerations. The king’s chief minister, Thomas Wolsey, stood as his godfather at his christening and he was openly acknowledged and proudly accepted by Henry VIII.

There have been several other candidates offered as possible natural children of Henry VIII. Ethelreda or Audrey Harrington, the daughter of Joan Dobson or Dingley, is believed to be an illegitimate daughter of Henry VIII. She married John Harrington and died in 1555. Mary Berkley, the wife of the courtier Sir Thomas Perrot, is also supposed to be the mother of two of Henry VIII’s illegitimate issue: Thomas Stukely, born in 1525, who married Anne Curtis and Sir John Perrot, who was born in 1527.

In the case of Sir John Perrot it is his physical attributes that have cast him as an illegitimate son of the king. Writing in 1867 his biographer claimed:

If we compare his picture, his qualities, his gesture and voice with that of the King, whose memory yet remains among us, they will plead strongly that he was a surreptitious child of the blood royal.3

Sir John Perrot went on to have a colourful career under the Tudors. Made a Knight of the Bath at the coronation of King Edward VI, he was briefly imprisoned in the Fleet Prison in the reign of Mary, served Elizabeth in a number of posts, notably Lord Deputy of Ireland, only to die in 1592 in disgrace for attempting rebellion against Queen Elizabeth. However, he was never officially acknowledged as a son of Henry VIII.

The poet and musician Richard Edwards has also been cast as a natural son of the king. Apparently born in March 1525, the evidence for his paternity is the fact that he received an Oxford education which his family could have ill-afforded to provide. His biographer writing in 1992 is confident that:

It would be difficult, if not impossible, to account for facts concerning Richard’s life beginning with his education at Oxford in any other way than as the son of Henry VIII who provided for his education and set the stage for the rest of Richard’s life.4

Richard Edwards’ career was rather less dramatic. After receiving his Master of Arts from Oxford, he was ordained. After a brief spell as Theologian at Christ Church, Oxford, much of his career was spent as one of the gentlemen of the Chapel Royal. However, once again, Henry VIII never took the opportunity to recognise him as his son.

Henry VIII’s most infamous alleged offspring are, of course, Mary Boleyn’s children, Henry and Catherine Carey. At least here it is possible to be absolutely certain that Mary Boleyn was in fact Henry’s mistress. Their affair began after her marriage to William Carey in February 1520. Speculation about the parentage of the children was first fuelled by attempts by Katherine of Aragon’s supporters to slander the Boleyns with the suggestion that Henry Carey was in fact Henry VIII’s bastard.5 In 1535 John Hale, the vicar of Isleworth in Middlesex, said that he had been shown ‘young Master Carey saying he was the King’s son.’ Such a tantalising prospect has been grist to the mill of historical debate ever since. New theories continue to be advanced in an attempt to prove conclusively that both were indeed Henry’s children.6

In each of these cases it can be argued that the women concerned were already married, something which could not be said of Elizabeth Blount when she began her liaison with the king. However, if Henry VIII’s morals would allow him to sleep with another man’s wife, would his conscience truly prevent him from acknowledging the child? Given that Henry was not exactly overendowed with legitimate issue, it seems reasonable to assume that he needed all the children he could lay claim to. When a marriage betrothal was the accepted way to seal a diplomatic treaty even a natural daughter could be a useful tool. If the child were a son, any arguments against acknowledging him would surely have been outweighed, if not by Henry’s pride in his achievement, then by his desperate need for other male relatives to help carry the burden of government.

Since Richmond was the only illegitimate son Henry VIII ever chose to acknowledge, it is tempting to conclude that he was the only illegitimate son he had. Writing in April 1538, regarding the arrangements for a proposed marriage between his eldest daughter Mary and Dom Luis of Portugal, Henry advised the Emperor, Charles V, that he was prepared to:

assure unto him and her and their posterity as much yearly rent as the late Duke of Richmond, our only bastard son had of our gift within this our realm.7

In a sense it does not matter whether Richmond was the king’s only bastard issue or not. What is most important is that he was the only one that Henry was prepared to acknowledge and employ on the wider political stage. The king’s precise intentions for Richmond’s long term prospects are, of course, a very different matter.

1

Mother of the King’s Son

According to the King’s Book of Payments, on 8 May 1513 Elizabeth Blount received 100s ‘upon a warrant signed for her last year’s wage ended at the annunciation of our Lady last past’.1 This indicates that she made her début at the court of King Henry VIII on 25 March 1512, when she was about twelve years old. The manner of her payment, which was not included in the regular lists of wages paid at the half-year and the amount, which was half the 200s per annum paid to the queen’s young maids of honour, suggests that she did not yet have a formal place in Katherine of Aragon’s household. Yet, even then, observers must have glimpsed something in the lively, fair-haired girl of those ‘rare ornaments of nature and education’ that were to mark her out as ‘the beauty of mistress piece of her time’.

Twelve was the minimum age that a girl could be accepted for a court position and competition for such places was fierce. Elizabeth was fortunate that her family conformed to the Tudor ideal of beauty, with fair skin, blue eyes and blonde hair. Equally praised for her skills in singing, dancing and ‘all goodly pastimes’ she was well suited to the glittering world of the court, with its masques, dances and endless occasions to impress. On the other hand, her ownership of a volume of Latin and English poetry by John Gower suggests this was no empty-headed moppet, but a girl with a lively mind to match her merry disposition, a quality which would no doubt have recommended her to an educated woman like Katherine of Aragon.

When a girl’s best chance of advancement was to make an advantageous marriage, Elizabeth’s parents must have hoped that she had made a good beginning. The prospect of a full-time position at court, mixing with some of the finest families in the realm, was the surest route to a beneficial match. However, they probably did not expect that one day their daughter would be the mother of the king’s son.

The peaceful accession of King Henry VIII on 21 April 1509 had been greeted with unrestrained delight. ‘All the world here is rejoicing in the possession of so great a Prince’ wrote William Blount, Lord Mountjoy. Here indeed was a prince among men. At around six foot three inches tall, Henry was, quite literally, head and shoulders above many of his contemporaries. Even the ambassadors of other realms were lavish in their praise of the young king. His skin was pink and healthy, his auburn hair shone like gold, his whole body was ‘admirably proportioned’. The epitome of vigour and youth, it was believed ‘nature could not have done more for him’.

Decades away from the bejowled colossus depicted in his last years, the man Elizabeth Blount would remember from their courtship made a stunning first impression. The Venetian Ambassador, Sebastian Giustinian, could hardly contain his admiration:

His Majesty is the handsomest potentate I ever set eyes on; above the usual height, with an extremely fine calf to his leg, his complexion fair and bright, with auburn hair combed straight and short in the French fashion, and a round face so very beautiful that it would become a pretty woman, his throat being rather long and thick.2

It was the best of new beginnings. The realm Henry had inherited was peaceful and prosperous. Unlike his father he had not been required to assert his claim to the crown on the battlefield. Nor was England to be burdened with the difficulties and dangers of a minority government. Best of all, despite being several weeks short of his eighteenth birthday when he ascended the throne, from the outset Henry VIII looked the king.

His impressive stature and handsome features inspired awe and admiration. Equally lauded for his athletic prowess with spear or sword, he was an accomplished rider, who hunted with such enthusiasm that he tired eight or ten horses in a day, not to mention those of his courtiers who did not share his formidable stamina. In an age when kings were still required to lead their forces in person, those who applauded his amazing feats in the jousts knew they might one day be called upon to follow this man into battle. At the very least, Henry’s abilities were a means to encourage his forces to greater glory. Also praised for his learning and other talents, the new king may well have merited the accolades, which were heaped upon him. Yet beneath the admiration must have been a significant degree of relief.

Of the children born to Henry VII and Elizabeth of York only three survived to adulthood. Two of those were daughters: Margaret, born in 1489, had married James IV of Scotland in 1503 and Mary, born in 1496, was betrothed to Charles of Castile. Of the three recorded sons, the death of the youngest, Edmund, in 1500, before he reached his second birthday was a natural disappointment. The death of the heir apparent, Arthur, Prince of Wales, in 1502 at the age of fifteen had been a devastating blow. Everyone was acutely aware that Henry VIII had been the sole male heir to the Tudor throne since the age of eleven. It was only good fortune that Henry VII survived until his heir was a respectable seventeen years old.

Although the youth of the thirteen-year-old Edward V had not been the only factor in Richard III’s unprecedented decision to usurp his nephew’s throne in 1483, it was universally accepted that a country needed a strong ruler if it were to thrive. Furthermore, the Tudors’ own claim to the throne was very recent. Henry VII’s reign had been troubled by the plots of the Yorkist pretenders Lambert Simnel, masquerading as the Earl of Warwick and more seriously, Perkin Warbeck posing as Richard, Duke of York. In addition, the genuine offspring of the House of York, in particular the nephews of Edward IV and Richard III, had reason to feel they had a better claim than any Tudor.

Henry VII made stalwart efforts to ensure the security of the succession.3 During the negotiations for Katherine of Aragon’s marriage to Arthur, Prince of Wales, the continued existence of Edward, Earl of Warwick, raised sufficient concern to warrant his execution, even though he was safely captive in the Tower. The offspring of Edward IV’s sister, Elizabeth de la Pole, were treated as a serious threat. When the question of who might succeed Henry VII arose in 1503, when Prince Henry was still a child of twelve, Sir Hugh Conway reported:

It happened the same time me to be among many great personages, the which fell in communication of the king’s grace, and of the world that should be after him if his grace happened to depart. Then, he said, that some of them spake of my lord of Buckingham, saying that he was a noble man and would be a royal ruler. Other there were that spake, he said, in like wise of your traitor, Edmund de la Pole, but none of them, he said, that spoke of my lord prince.4

The threat would not be extinguished easily. Henry VII secured the return from exile of Edmund de la Pole in 1506 and confined him in the Tower. However, his brother Richard remained at large and would be a thorn in Henry’s side for some years to come.

In 1513, as Henry VIII prepared for war in France, Richard de la Pole persuaded the King of France, Louis XII, to recognise him as King Richard IV. Henry was sufficiently concerned by the danger that this represented to order the execution of Edmund before crossing the Channel. The Duke of Buckingham, whose own claim to the throne was derived from Edward III, profited little from this ominous example. Amid claims that he intended to usurp the throne, he was executed in his turn in 1521. Henry VIII was all too aware that the only way to secure the Tudor dynasty’s grip on the crown was to produce a viable male heir.

That Henry VIII chose to make Katherine of Aragon his bride must be seen, at least in part, as a response to this pressing need. Although the couple had been betrothed since 1503, their union was by no means a foregone conclusion. The youngest daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, Katherine had come to England in 1501 to marry Henry’s elder brother Arthur, then Prince of Wales. After Arthur’s sudden death in 1502 Henry VII had decided that his interests would be best served by preserving this alliance. After some negotiation it was agreed that Katherine should marry the twelve-year-old Prince Henry as soon as he had completed his fourteenth year on 28 June 1506. Yet as that time approached, Henry VII became increasingly uncertain that this was the best possible match for his only remaining son and heir.

In 1505 Prince Henry, at his father’s instigation, made a formal protest against the contract made during his minority. In 1506 Henry might describe his betrothed as ‘my most dear and well-beloved consort, the Princess, my wife’, but his father was looking at other possibilities. Once Henry VIII became king in 1509, several questions, not least the important matter of Katherine’s dowry and rival negotiations for a marriage to Eleanor, the daughter of Philip of Burgundy, were simply swept aside.5 After seven years of dispute and delay Henry VIII married Katherine of Aragon just six weeks after his accession.

At twenty-three Katherine was ‘the most beautiful creature in the world’, still blessed with the fresh complexion and long auburn hair that had entranced observers at her arrival in England. She was also of an age to bear children, something that could not be said of the eleven-year-old Eleanor. Henry’s excuse that the marriage was his father’s dying wish was conveniently difficult to disprove. Shortly afterwards he wrote to his new father-in-law, ‘If I were still free I would choose her for wife above all others’. There can be little doubt that Henry was eager to marry Katherine and chose to exercise his new found authority to settle the matter.

Henry and Katherine were wed on 11 June 1509 at the Church of the Observant Franciscans at Greenwich. Despite the difficulties created by Henry VII, it was a most suitable match. Katherine was descended from one of the most respected royal houses in Europe and her pedigree would do much to bolster the credibility of the fledgling Tudor dynasty. Henry VIII was fired with the desire to reclaim the English crown’s ancient rights in France; from the outset his attitude was clear. The policy of peace and security followed by his father would not be his, far better was the esteem and respect earned by success in campaigns and the glory and honour that came from dispensing the spoils of war. ‘I ask peace of the king of France, who dare not look at me let alone make war!’ he thundered. Katherine’s support, or more to the point that of his new father-in-law, seemed to place all this within his grasp.

Katherine’s piety was also a desirable attribute in a queen, encouraging God’s blessings on the realm. When Henry was so determined to seek glory by waging war on his fellow Christians, always a complex moral issue despite appearances to the contrary, her devotional and charitable activities would help redress the balance. It is also clear that the couple themselves enjoyed a warm and mutually satisfactory relationship. ‘The Queen must see this’ or ‘This will please the Queen’, Henry would enthuse. In her turn Katherine bore Henry’s boyish japes with affectionate indulgence. However, it was widely acknowledged that ‘Princes do not marry for love. They take wives only to beget children’.

The importance of fecundity was evident in Katherine’s chosen emblem. The pomegranate was not just a representation of her homeland, but also a symbol of fertility. Sir Thomas More had good reason to believe that she would be ‘the mother of Kings as great as her ancestors’: Katherine came from a family of five surviving children and her sister Juana produced a brood of six children. At first it seemed as if the queen would have little problem in fulfilling the nation’s expectations. Only four and a half months after the wedding Henry was able to advise his father-in-law that ‘the child in the womb was alive’. That this pregnancy ended with a stillborn daughter at seven months was a disappointment but not a disaster. Such things were not unusual. Katherine and Henry had at least proved their fertility and therefore it was only a matter of time before she conceived again. Indeed, when Katherine wrote to advise her father of the miscarriage, she was already pregnant again.

It is perhaps no coincidence that the first indication of any infidelity on the king’s part occurs at this time. Sex during pregnancy was generally discouraged as being harmful to the health of the mother and the unborn child. While it is doubtful that every husband followed this recommendation, Henry had more reason than most to be careful of his wife’s condition. However, despite the rumours, it is by no means certain how far, if at all, Henry strayed. In 1510, the Spanish ambassador, Don Luis Caroz reported that one of the young, married sisters of the Duke of Buckingham had attracted the attention of the king. According to the ambassador, Sir William Compton, a favoured companion of Henry, had been seen courting Lady Anne Hastings. Perhaps because Compton was no fit paramour for a duke’s sister it was thought that he was acting on Henry’s behalf.

The ambassador reported, with some glee, the dramatic scenes that ensued when another sister, Lady Elizabeth Ratcliffe, informed the duke of Compton’s behaviour. Buckingham quarrelled with Compton and the king before storming from the court. Anne was carried off by her husband to the safety of a nunnery and Henry ordered an emotional Katherine to dismiss Elizabeth for her meddling. Henry was clearly angry, but none of this makes it clear whether Compton or the king was in fact the guilty party. Garrett Mattingly suggests that the ambassador was relying on gossip fed to him by one of Katherine’s former ladies-in-waiting, Francesca de Carceres. If this was the case, neither of them was sufficiently close to the centre of things to know exactly what had been going on. Since Don Luis was primarily concerned with demonstrating how much Katherine was in need of his advice and counsel, he was probably all too willing to believe that the incident was more significant than it really was.

It is possible that Henry did engage in a degree of harmless flirtation with the Lady Anne in the tradition of courtly love. In 1513 her new year’s gift from the king was a suspiciously extravagant thirty ounces of silver gilt. As the third most expensive present that year, it was ‘an unusually high amount to be given to one of the queen’s ladies by Henry’.6 The elaborate game of courtly love, with its exchange of tokens and protestations of undying devotion, was a popular pastime at the Tudor court. Enthusiastically played by all of the queen’s ladies and the king’s courtiers, it was not in itself evidence of a serious attraction. Like any game it had rules, which were supposed to be observed. Those occasions when the heartfelt sighs overstepped the boundaries into genuine emotion were cause for anger and recrimination, as Henry Percy found to his cost when his romantic pursuit of Anne Boleyn exceeded accepted limits.

Although Katherine was exempt, since propriety required that the only man who romanced her was her husband, Henry was a keen player. Yet it is significant that none of Henry’s known mistresses came from families above the rank of knighthood. It was one thing to pay homage to a duke’s sister as an unreachable goddess, but quite another to seduce her. While Henry’s conduct may have encouraged suspicion among the gossips, subsequent events indicate that Sir William Compton’s attraction to Lady Anne Hastings was the genuine article. In 1527 Wolsey drew up a citation accusing Compton of adultery with Anne. Compton apparently took the sacrament in order to disprove his guilt. However, his will belies his protestations of innocence. Not only did he ask for daily service in praying for Anne’s soul, but also the profits from certain of his lands in Leicestershire were earmarked for her use for the remainder of her life.7

On New Year’s Day 1511 Katherine of Aragon was safely delivered of a son. At only her second attempt she had fulfilled her ultimate duty and provided England with a male heir. The child was ‘the most joy and comfort that might be to her and to the realm of England’. The baby was apparently healthy and there was no reason to suppose that the little prince would not be joined shortly by a host of brothers and sisters. Yet only fifty-two days later the child was dead. The grief and shock of both his parents at this bitter blow was echoed by the whole nation. It can have been of little comfort to Katherine that unlike a miscarriage or a stillbirth, which was universally looked on as the fault of the mother, infant mortality was seen as God’s judgment on both parents for their sins. To make matters worse, this time Katherine did not conceive again for another two years.

The idea that Henry might have spurned his wife for the pleasures of other women seems an empty revenge for a man who was so desperate to secure a legitimate heir. If he did there is no evidence of it. In contrast to many of his contemporaries Henry was a model of restraint and discretion. Fidelity was not a prerequisite for a king, who generally married for financial and political advantage rather than for love. Nevertheless, Henry is only known to have had a handful of mistresses and never more than one at a time. Given Katherine’s indisposition during successive pregnancies, few would have rebuked him for occasionally seeking solace elsewhere. Exactly how Etiennette la Baume, a young lady from the court of the Archduchess Margaret of Savoy, extracted the promise of a dower of 100,000 crowns from the King of England can only be imagined. Yet until the queen was known to be with child Henry had every incentive to concentrate his attentions on his wife.

Since Katherine was still only twenty-five, her age should not have been a bar to conception. Jane Seymour was twenty-eight and Anne Boleyn already in her thirties when they conceived. Unfortunately, his grief over the loss of his infant son may have proved too great a distraction. Henry’s relationships all suggest that he was a slave to his emotions. If his antipathy to Anne of Cleves was enough to ensure he could not ‘do the deed’, perhaps his shattered confidence after this devastating loss meant that, despite his best efforts, England still waited expectantly for the much-desired male heir.

It was in the wake of this latest disappointment that Elizabeth Blount made her formal début at the court of Henry VIII. That she secured an entrée into the queen’s household as soon as she reached a suitable age was a testament to her more than average attributes. Although Henry had been King of England for just three years, his court was rapidly gaining a reputation as one of the most spectacular in Europe. It had long been established that it was the duty of a monarch to spend his money ‘not only wisely, but also lavishly’. Even the parsimonious Henry VII had realised the benefit of extravagant display to make a political point. It might take the young Henry VIII years to earn the kind of reputation enjoyed by seasoned monarchs like Ferdinand of Aragon, but in the meantime he would boast a court to rival the best in Christendom.

Life was a round of music, dancing and entertainments, with elaborately staged tournaments, spectacular pageants and fashionable Italian masques. The revels were accompanied by some of the finest singers and musicians from England and abroad. The gold and silver on display, the many lavish clothes and the numerous sparkling jewels, were designed to impress. The beauty of the queen’s ladies was especially remarked upon. In June 1512 the ladies of the court, resplendent in red and white silk, danced in an elaborate pageant, featuring a fountain fashioned from russet silk to mark the jousts at Greenwich. At Christmas that year the festivities were capped by the appearance of a fabulous mountain from which six ladies, dressed in crimson satin and adorned with gold and pearls, emerged to dance. In the midst of such splendour it is perhaps no surprise that Elizabeth’s arrival caused no great impact. She was, after all, still very young and engaged in a very junior position. It is unlikely that she would have progressed this far unless it was intended that she would be granted a regular place in the queen’s service as soon as a suitable post fell vacant.

Her success was probably primarily due to the influence of William Blount, the 4th Lord Mountjoy. Sometimes described as Mountjoy’s sister or his niece, Elizabeth’s exact relationship with him was rather more distant, their last common ancestor having died in 1358.8 However, the two branches of the family had a long history of mutual support and assistance. In 1374 Elizabeth’s ancestor, Sir John Blount, had conveyed a significant part of his inheritance to his half-brother, Walter Blount, the forbear of the Blounts, Lords Mountjoy. In 1456 Elizabeth’s great-grandfather, Humphrey Blount, had fought alongside Walter Blount, later 1st Baron Mountjoy, against King Henry VI’s forces at Ludlow. The present Lord Mountjoy was a trustee of Elizabeth’s parents’ marriage settlement and would be instrumental in ensuring that they were able to enjoy their rightful inheritance.

An established figure at the Tudor court, Mountjoy had served Henry VII before being appointed Master of the Mint by Henry VIII in 1509. Since he was also the husband of Agnes de Venegas, one of the few Spanish ladies-in-waiting who had remained in England with Katherine of Aragon, he was well placed to smooth Elizabeth’s entry into the Queen’s service. In any case, his appointment as Katherine of Aragon’s chamberlain on 8 May 1512 must have been a significant factor in her continuing success. Since Mountjoy was now the chief officer of the queen’s household it was perhaps no hardship to see that his attractive and accomplished young relative was granted the next vacancy. From Michaelmas 1512 Elizabeth joined the ranks of the queen’s maids of honour, under the watchful eye of Mrs Stoner, ‘the mother of the maids’, at the full wages of 200s per annum.9

In many respects Elizabeth was ideal mistress material: sufficiently well born to actually meet Henry, sufficiently accomplished and interesting to catch his eye, yet of a status where her prospects would be enhanced, rather than her reputation diminished, by a liaison with the king. Her family, the Blounts of Kinlet, were a cadet branch of an established and extensive family. Originally from Staffordshire, they still enjoyed estates in Balterley and other places in the county which they had held since the fourteenth century. Elizabeth’s great-greatgrandfather, who died in 1442, was described as ‘Sir John Blount of Balterley’. The family had acquired the Lordship of Kinlet in Shropshire through a piece of fortunate misfortune, when all four of the male heirs died without issue. In a grant dated 2 February 1450 Elizabeth’s great-grandfather, was described as ‘Humphrey Blount of Kinlet’.

The Blounts of Kinlet were county rather than court. They served their king as sheriffs, escheators and justices of the peace, occasionally representing Shropshire in parliament. However, the local nature of their offices did not make them immune from the tremors of wider concerns. Humphrey Blount earned his knighthood fighting to secure Edward IV’s throne at the Battle of Tewkesbury in 1471. Yet none of Elizabeth’s immediate relatives ever rose above the rank of knight. Prosperous rather than wealthy, Sir Humphrey Blount’s will included a gold collar for his eldest son, Thomas, a gold cross for his second son, John, a gold chain to be sold to pay for masses for his soul and there were a few pieces of plate and several gowns, both furred and velvet, as well as a doublet of red damask. Yet while his two eldest sons both received gilt swords, the youngest son, William, had to make do, not with a sword at all, but a gilt wood knife. Similarly, his daughter Mary was allowed 120 marks towards her marriage. However, this significant sum was not available in ready cash, but represented money owed to him by the Bishop of Durham.10

When Elizabeth made her début at the court of Henry VIII, the head of the family was her grandfather, Sir Thomas Blount. A man of some local eminence, he had first served as Sheriff of Shropshire in 1479 when he was twenty-three years old. He had earned his knighthood fighting to defend Henry VII’s title to the throne at the Battle of Stoke on 16 June 1487. Never much of a courtier, his appearances were confined to great ceremonial occasions, like the coronation of Elizabeth of York on 25 November 1487; his own interests remained firmly centred on the shires. In 1491 his lands in Shropshire were considered to be worth a respectable £108 10s and he would remain a significant force in county politics until his death in 1524.11

However, in the winter of 1501, the Blounts must have felt that all the opportunities of the court in London had arrived on their doorstep. The heir apparent, Arthur, Prince of Wales and his new bride, Katherine of Aragon established their household at Ludlow in Shropshire. Sir Thomas Blount’s marriage to Anne Croft, the eldest daughter of Sir Richard Croft, one of Arthur’s principal officers, ensured the Blounts were welcome visitors. Regrettably, the chance was short-lived. On 2 April 1502 Prince Arthur died and Katherine was recalled to London. Yet many of Katherine of Aragon’s enduring memories of her initial time in England would not have been of the London nobility, but of the gentry who flocked to salute her at Ludlow. The Blounts may well have utilised this connection to smooth Elizabeth’s acceptance as a maid of honour in the queen’s household.

Elizabeth was the second daughter of the eight surviving children of John and Katherine Blount.12 She cannot have been born until at least 1499, the year after her parents consummated their marriage, and since she had to be at least twelve to take up a court post, she must have been born before March 1500. She probably spent much of her childhood in Shropshire or Staffordshire, yet any concept of Elizabeth as a simple, rural girl plucked from the shires would be misleading. In the years prior to her formal appointment as a maid of honour to Katherine of Aragon, she had had several opportunities to come to court.

As an esquire of the body to Henry VII, her father was one of those granted livery from the crown at his funeral in 1509. At the coronation of Henry VIII, he was among the assembly of the King’s Spears. Modelled on the corps formed by Louis XI, the Spears were a group of about fifty gentlemen and sons of noblemen under the captaincy of the Earl of Essex. It was both a military and a ceremonial appointment. The regulations were martial in tone and exercise in arms was a primary function. The Spears were to play a significant part in the French war of 1513. However, in their distinctive crimson uniforms, they also took an active part in the colourful pageantry of Henry VIII’s court. When Leonard Spinelly, delivered to the king the cap and sword presented by Pope Leo X in 1514, he was met at Blackheath by a host of dignitaries escorted by all the Spears. Since the regulations required ‘their rooms and their board to be provided at the king’s pleasure’ and commanded them to lodge where the king decided,13 John Blount’s duties were ample reason and excuse to bring him to court.

While there is no evidence that his family always accompanied him, it is unlikely that he would have missed the chance to show off such a promising young daughter. At the very least, Elizabeth might secure entry into some noble household, much as her uncle, Robert Blount, was accepted into the service of the Earl of Shrewsbury. Although S.J. Gunn has termed membership of the King’s Spears as ‘belonging to only a very broad charmed circle’14 it did bring John Blount into the same orbit as men of influence, like Charles Brandon, later Duke of Suffolk. Since the exact nature of Brandon’s relationship with Elizabeth has been the cause of some speculation, it should be borne in mind that he would have been sufficiently acquainted with her family to have more than a passing familiarity with the pretty, blonde child.

Elizabeth also had other kin and allies who could help smooth her path at court. Her relationship through the Crofts, her paternal grandmother’s family, with the Master of the Revels, Sir Edward Guilford, would have helped to ensure that she did not remain a wallflower for very long. Her great-uncle, Sir Edward Darrell of Littlecote in Wiltshire, later Katherine of Aragon’s vice-chamberlain, was already well known to the queen, having been one of those appointed to escort her on her arrival in England in 1501. Elizabeth could also claim kinship with the Stanleys, the Earls of Derby, through her maternal grandmother, Isabel Stanley, and while her relationship to the Suttons, the Lords Dudley, was rather more distant, being rooted in her great-grandfather’s wardship to John Sutton, Lord Dudley in 1443, such things mattered little if presuming on the acquaintance might produce a favourable result.

Yet all her connections would have come to nothing if she herself had not been able to create a good impression. Elizabeth Blount was clearly something out of the ordinary. When the Dean of Westbury, one of Anne Boleyn’s supporters, was asked to compare Elizabeth to Anne in 1532, he thought Elizabeth was the most beautiful.15 Even twenty years later the king’s cousin, Lord Leonard Grey, could still declare that he had ‘had very good cheer’ when visiting with her in Lincolnshire. At twelve she would have been expected to be well schooled in needlework and in all those aspects of learning which were a desirable part of any ambitious girl’s repertoire. Elizabeth’s primary purpose in being at court was to attract a suitable husband and the queen’s household was an ideal place to cultivate those skills and accomplishments which would do so, and the slightly different talents expected of the ideal Tudor wife.

A contemporary reported that Katherine of Aragon ‘set a high moral tone for her Household’. Although the queen’s excessive piety belongs to a later date, no doubt a considerable part of Elizabeth’s day would have been spent accompanying the queen in her devotions, hearing mass and divine offices. The young maid of honour would also have been required to attend the queen at meals and in the presence of visitors and foreign ambassadors. Katherine of Aragon prided herself on embroidering her husband’s shirts herself, like any good wife, and the queen and her ladies would have spent many a companionable hour sewing together. Whatever proficiency Elizabeth had in Latin was perhaps a legacy from her time in Katherine’s service. The queen herself may have encouraged her young attendant in her studies of the language, much as she did with her sister-in-law, Mary Tudor. Elizabeth would also have learnt by, arguably, the best example in the realm, the duties and responsibilities of a great noblewoman: not only to dispense care and succour through her charitable deeds, but to manage her own household and estates. This example must have stood Elizabeth in good stead in later life when she presided over her own interests.

In the meantime, while Elizabeth’s duties required her to be both an asset and ornament to the court and her family saw her primary duty as making a good marriage, Elizabeth had plenty of opportunities to have a good time. Although Katherine did not choose to dance in public, in the privacy of her own apartments she would often dance with her ladies. Sometimes there would be music and singing, at other times there might be table games like cards or dice. Often the king and his attendants would join the queen and her ladies, on occasion putting on one of his elaborate disguises when everyone would pretend not to recognise the handsome stranger and his fellows until he was unmasked. Given that few men could match Henry’s distinctive stature as he towered over his courtiers, these episodes may have been rather more amusing than the king intended to the queen’s ladies, as they watched their mistress feign astonished surprise.

In the summer of 1513 this idyll was interrupted for a time when the pleasures of the court were put aside in favour of the splendour of martial deeds. So far, Henry’s warlike exploits had been a disappointment. A previous military venture, under the command of Thomas Grey, Marquess of Dorset in 1512, had ended in disaster when the English armies at Fuentarrabia had waited in vain for the expected Spanish reinforcements. The English army disintegrated into disorder and disease ‘which caused the blood so to boil in their bellies that there fell sick three thousand of the flux’. When, on the point of mutiny, they fled for home, Ferdinand added insult to injury by blaming them for the lost opportunity. The true fault lay with Ferdinand who had concentrated on his own personal objectives of obtaining Navarre at the expense of Henry’s ambitions. However, eager to prove himself in battle, Henry decided to lead his forces in person.

All who could be spared followed their king to France. Even Elizabeth’s grandfather, Sir Thomas Blount, now in his fifty-seventh year, went as a captain in the retinue of the Earl of Shrewsbury. For a time Elizabeth was almost bereft of male relatives at court, her father and her uncles all being included in the party which sailed across the Channel, although Lord Mountjoy did remain behind until September as one of those appointed to advise Queen Katherine in her role as regent.

The threat of the Scots ensured that it was not entirely a quiet time at court, although it is doubtful that Elizabeth enjoyed being ‘horribly busy’ in the making of standards, banners and badges against the hostilities (as Katherine proudly reported to her husband) quite as much as singing or dancing. The king’s return in October was an occasion for both triumph and sadness. The victories at Flodden and Tournai were a marked success for the new reign, but, in the wake of the celebrations on 8 October 1513, it was reported that the queen had been delivered early of a son.16 This was Katherine’s third pregnancy in four years of marriage. This time everyone must have hoped that the odds were in favour of a successful outcome. However, it was not to be. When God had already blessed England with such good fortune in battle, it must have seemed especially cruel to withhold the much-desired heir. That Henry and Katherine remained childless was a personal tragedy for them; however, as long as the realm was without a male heir their private grief was also a matter of public concern.

Henry VIII’s relationship with Elizabeth Blount is often thought to have begun as early as the winter of 1513 upon Henry’s return from France, perhaps in the wake of Katherine’s latest miscarriage. Writing to the king from France in 1514, Charles Brandon, recently created Duke of Suffolk, had a special message for Elizabeth and her young associate Elizabeth Carew, another of the maids of honour:

and I beseech your Grace to [tell] Mistress Blount and Mistress Carew, the next time that I write unto them [or s] end them tokens, they shall either [wri]te to me or send me tokens again.17

The letter has caused some modern authors to speculate that Elizabeth may have been Suffolk’s mistress before she was the king’s. Suffolk was notoriously charming and handsome. He was also one of the few men whose marital history could rival the king’s for scandal and complexity.18 Elizabeth herself is not traditionally cast as shy and retiring, but nor is there any hint of the kind of notoriety earned by Mary Boleyn, who was once described as ‘a very great wanton with a most infamous reputation’.19 The exchange of tokens was a conventional part of the elaborate game of courtly love and this may have been nothing more than what it appears, a piece of harmless flirtation.

Elizabeth could be charming and gracious, but when it came to matters of the heart she clearly knew her own mind. When the king’s cousin Lord Leonard Grey, a younger son of the Marquess of Dorset, first expressed his interest in marrying her in May 1532, he wrote to Thomas Cromwell asking the secretary to approach Elizabeth on his behalf. During an obviously enjoyable visit to Elizabeth’s house at Kyme he dashed off a note, hoping that Cromwell would also persuade the king and the Duke of Norfolk to back his suit, even sending blank paper for their letters and £5 in gold for Cromwell’s cooperation. He was very keen, assuring Cromwell that he would ‘rather obtain that matter than to be made lord of as much goods and lands as any noble man hath within this realm’, although, Elizabeth’s substantial estates may also have had their own attraction. Cromwell was happy to oblige, but Elizabeth was not to be persuaded. In July 1532 Grey plaintively stressed the king’s acquiescence to the match, even as he urged Cromwell to try harder to secure Elizabeth’s agreement.20

Even though she succumbed to the king’s attentions, it does not make her a loose woman. Putting aside the fact that Henry was rather difficult to refuse, Elizabeth may well have been attracted to him and she could also rest assured that their liaison would bring her some benefit. In the light of the way Suffolk had treated his wives, Elizabeth ought to have been more wary of risking her reputation by a casual sexual relationship with him, if she had any hopes of subsequently making a respectable marriage.

The assumption that Henry and Elizabeth were already romantically involved has been fuelled by Elizabeth’s appearance in a masque during the Christmas celebrations in 1514. Dressed in blue velvet and cloth of gold, styled after the fashions of Savoy, she was one of four lords and four ladies who ‘came into the Queen’s chamber with great light of torches and danced a great season’. When at last the dancing was over these mysterious revellers took off their masks and Elizabeth Blount’s partner was revealed as Henry VIII.

If Katherine was worried, it was not at the spectacle of her husband dancing with a slip of a girl. Recent months had seen strained relations at court as Henry grew increasingly frustrated at a Spanish alliance that had not brought him the gains he had expected. The Spanish ambassador complained mournfully that he felt like ‘a bull at whom everyone throws darts’. Katherine’s confessor, Fray Diego Fernandez, accused Henry of having treated the queen badly. Rumours circulated that Henry was planning to put aside his childless wife in order to marry a daughter of the Duke of Bourbon. Katherine no doubt bore the brunt of her husband’s ire at her father, but their marriage was not in doubt. Not only had Henry considered avenging himself on Ferdinand by asserting Katherine’s claim to her mother’s kingdom of Castile, but also by the autumn of 1514 he had succeeded in making his twenty-eight-year-old wife pregnant for the fourth time.

Once Katherine was known to be with child Henry may well have felt at liberty to stray, but the object of his affections was probably not the fourteen-year-old Elizabeth Blount. A few nights after the entertainments in the queen’s chamber at Christmas 1514, Henry took part in the Twelfth Night masque at Eltham. This time he had a different partner. Jane (or Jeanne) Poppingcourt was a Frenchwoman who had originally been employed by Henry VII as a companion to his daughters. By 1502 Jane was serving as one of Mary Tudor’s maids of honour and by 1512 she was receiving 200s per annum as a member of the queen’s household. Jane continued to feature in the court revels until she returned to France in 1516.