Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

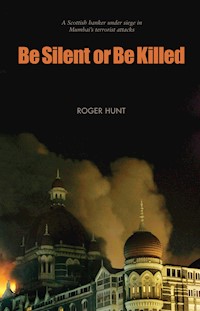

On 26 November 2008, India came under a series of horrific terrorist attacks which killed more than 150 people, and injured hundreds more. Scottish banker Roger Hunt was staying at the Oberoi Trident Hotel in Mumbai and found himself caught up in the siege. Trapped in his hotel room, defenceless against the suicidal terrorists killing people in cold blood, Roger was forced to rely on his instinct. This account of a terrifying ordeal is at once poignant, gripping and captivating in its raw, honest narration of an ordinary man thrown into the path of danger and pushed to the limit in his struggle for survival. Review: Roger Hunt had just finished dinner in Mumbai's five-star Oberoi Hotel when a waitress tried tempting him with the desserts on offer. But he decided against another course. It was the first of a series of decisions that would save his life, as the restaurant was strafed with machine gun fire just a few minutes later. DAILY RECORD

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 279

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ROGER HUNT is from the North East of Scotland and has spent the majority of his career working in management positions within the Royal Bank of Scotland. In 2008 Roger was caught up in the terrorist attacks in Mumbai, and knows just how miraculous it was that he came out of the flame-swept Oberoi Trident Hotel alive. Roger left RBS to join the Scottish Prison Service, where he was HR Manager for HMP Peterhead and HMP Aberdeen for almost two years. He currently works for British Airport Authority (BAA) as Head of Human Resources based in Aberdeen airport. Following the attacks, Roger has shared some of his experiences live on STV's The Hour, spoken at Grampian Police's Annual Conference and been regularly involved in activities supporting Counter Terrorism. Roger lives in Macduff with his wife and three children. Be Silent or Be Killed is his first book.

Be Silent or Be Killed

A Scottish banker under siege in Mumbai's terrorist attacks

ROGER HUNT

LuathPress Limited

EDINBURGH

www.luath.co.uk

First published 2010 by Corskie Press

This edition 2011

eBook 2013

ISBN (print): 978-1906817-76-3

ISBN (eBook): 978-1-909912-03-8

The author's right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

© Roger Hunt and Kenny Kemp 2010, 2011

To Irene, Lisa, Christopher and Stephanie

And in memory of all those who lost their lives in the 26 November 2008 terrorist attacks in Mumbai

Contents

Acknowledgements

Foreword

My Own Mumbai Horror

Finding My Anchor

Losing a Brother at Sea

Upwardly Mobile

Return to India

A Grand Arrival

An Indian Wedding

Lifesaving Birthday Cake

Murderous Mumbai

The Lobby of Death

Survival Tactics

HQ Kicks into Action

Phoning Home

Slaughter at My Door

Dead or Alive?

Stalked by Fear

Back in Touch

Caught in a Gun Battle

Life or Death at Gunpoint

The Acrid Taste of Freedom

Family Reunion

Aftermath

Verdict

Pictures

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I'VE WRITTEN THIS BOOK for a reason. It's part of my own process of coming to terms with being caught in what was known as India's 9/11. Why did I live when so many other people died? I'm sure it's a question that runs through the mind of all survivors of a major catastrophe.

I wanted my family, friends and colleagues to understand a bit more about my perilous position in Mumbai between late on Wednesday 26 November 2008 until the afternoon of Friday 28 November. I've been asked so often about the situation, I thought it best to simply tell the tale, as it happened, without frills or embellishment. In particular, I knew that my children were keen to know what happened to me. Yet, it never felt that there was a right time – or indeed way – of sharing the details. Writing a book would give them the chance to know and understand every detail at a time that suited them individually. Above all, I also wanted people to know that they played a significant role too. There were many friends and colleagues who worked hard to keep me alive, raise my spirits and get me back home safely. So I would like to thank them for making this true story possible and for the part that each and every one of them played in ensuring that I returned home safe to my family, my second chance at life.

I'd liked to thank MI5, Hostage and Crisis Negotiation Unit, and the Black Cats – to whom I owe my life.

At RBS Gogarburn in Edinburgh, Lynne Highway, Acting HR Director, Andrew Sharman, Pete Philp, Lesley Laird, Karlynn Sokoluk, Lorraine Kneebone, Stan Hosie, Incident Management, my other senior colleagues in Policy & Advice Services and the many colleagues who supported me upon my return to work. A huge thank you also goes to Gavin Reid, the RBS man in Mumbai, for providing me with a safe haven upon my release and escorting me every inch of the way back from India to Scotland.

In Macduff, I would like to thank our family and friends for their vital support both during and after the terror attacks. They have been a great source of support and comfort and a major part of the healing process for myself, Irene and our children. In particular Abby, Irene's dad, and her sisters Karine and Carole. A great deal of thanks is also due to the staff at Macduff Primary School for all of their support both during Irene's absence and return to work.

I'd also like to thank Frank Docherty, of Career Associates in Edinburgh, who introduced me to the writer and journalist Kenny Kemp. Kenny has spent time with me and Irene turning my taped thoughts into a proper and compelling narrative. In addition to benefiting from his professional writing skills we have also acquired a great friend. I am also grateful for support from Jennie Renton and Dave Gilchrist in the completion of my book.

Finally, a message to any unfortunate person who finds themselves in a situation similar to mine: No matter how difficult the circumstances you find yourself in, when all may seem lost, never ever give up.

Roger Hunt June 2010

FOREWORD

HARDLY A DAY goes by without some terrorist atrocity hitting the headlines around the world. The death tolls vary, but these barbaric acts always involve the slaughter and maiming of innocent human beings. London. Moscow. Madrid. Kabul. Karachi. New York. And then there was Mumbai. For a few days towards the end of 2008, India's financial and commercial centre was in the full glare of the world's media spotlight as a brutal life and death struggle unfolded on our television screens.

Roger Hunt was caught up in the killing. And he survived. Just. Roger is a regular guy from the North East of Scotland. He and his wife, Irene, and family are hard-working Scots who want to enjoy their lives. They have never gone looking for fame or the limelight. But life throws up so many different paths.

When Roger became involved in the Mumbai terrorist attacks in November 2008, he was put to the ultimate test. For two days, his life hung on a thin piece of thread – and he was forced to make calculated decisions that would ultimately save his skin. Roger Hunt's story is a tale of our modern 21st century times. It is about how individuals become wrapped up in our increasing global world. It is about raw fear and dangerous uncertainty; about resilience, common sense and calmness; and, ultimately, about the sustaining power of love.

For those who say Roger should never have been in India in the first place there is one important point to be made. For generations, Scots have gone around the world on business and for commercial reasons. As a small nation, it's an ingrained part of our intrepid character. Roger Hunt was simply doing his job with the Royal Bank of Scotland. And here there is another central aspect to this story. Roger's developing career came about because RBS was growing into one of the world's leading banks. This created opportunities and challenges, and Roger's story is played out against this and the wider backdrop of the international banking crisis of October 2008, which led to the collapse of RBS and its bail-out by the British taxpayer to the tune of 45.5 billion pounds.

If there is a message, it is that those who seek to kill and maim innocent people with machine guns and bombs must not be allowed to prevail.

Roger Hunt came out of this with a great admiration for the people of India and how they coped with the tragedy: he salutes their spirit and resolve. He knows how lucky he is to have survived to tell his remarkable tale. He tells it as it happened with no frills and no exaggeration: simply, the honest truth.

Kenny Kemp June 2010

CHAPTER ONE

My Own Mumbai Horror

MY HEART WAS POUNDING through my ribcage. After hour upon hour of silence, broken only by intermittent machine gun fire and exploding grenades, there was a violent crash in the hotel room next door.

For 60 hours without sleep, as tiredness crept in, my senses had been in an acute state of crisis – especially my hearing. Now my pulse quickened. I sat up and strained my ears as the noise next door increased and I heard muffled shouts. Then silence. I was listening for even the faintest creak on the floor. Outside the window, the crows croaked and cackled as they circled in the air.

An instruction was barked out and then another voice called out in fear. This must be the attackers systematically 'clearing' each room, I thought, and imagined them murdering the defenceless occupants.

For 15 long minutes I strained to listen. Petrified as never before, I made not a sound. Then I heard scuffling right outside my door. This was it. It was all over for me. I took a deep breath of air gritty with smoke. Was I about to be blasted to kingdom come, was there any chance my ordeal would end in release and a return to freedom?

Earlier I had dragged the brown leather couch into a corner, then I had climbed in behind it and crouched down out of sight. I had been in this position for nearly two days, without eating, drinking or visiting the toilet. I had been lying so long on my side that my right arm was completely numb and I couldn't move it. The cramped position was also very painful… but adrenalin overcame any injury when I heard a voice shout:

'Open the door! Open the door!'

As a band of terrorists swept across Mumbai, I had been pinned down in this room on the 14th floor of the Oberoi Hotel for two days. My tactics had been to lie low – literally – and if it came to it, conceal my identity. I had witnessed the killers slaughtering my fellow guests in the foyer. I had listened as these murderers moved from room to room, shooting any Western visitors they discovered. I stuck to my plan to stay in hiding and not attract any attention, even as a fire gripped the hotel and smoke made it difficult to breathe.

But now surely it was my turn. Even if the men in the corridor were friendly forces here to rescue me I didn't want to take a chance. I had been using my Blackberry to communicate with the outside world and I'd been advised that if this happened, I should stand up with my arms raised. But my sense of survival overruled this.

My mind was racing: what if this was the terrorists and not a rescue party? If I followed this instruction, I was going to give them an easy target. There was no doubt these ruthless gunmen would kill me.

There was a terrific crash and the heavy wooden door burst open. Still cowering behind the large settee, which acted as a sort of barricade, I could hear quick and heavy footsteps sweeping into the room, and then the click, clack of metallic weapons. I heard the safety catches of automatic weapons clicked off. And then the curtains were pulled back and brightness invaded the fetid darkness.

If this was the killers, my time was up – and equally, if this was the Indian Black Cat commandos, any sudden movement from me now might cause them to open fire in panic.

I was caught between life and death and the problem of how to reveal myself to the strangers in my room. I'd kept a small knife beside me. But it would be useless against a machine gun, so I slid it under the couch and yelled, 'Please don't shoot!'

The barrel of a sub-machine gun came prodding over the top of the couch. I tried to pull myself up – but my right arm was so numb I couldn't get it into the air. The three armed men wore dark clothing, without markings – as had the death squad I had seen two days earlier blasting away the diners in the Tiffin and Kandahar restaurants downstairs.

Very shakily, I just about managed to stand, when a hand gripped me and pushed me back against the wall. I was almost too exhausted to care, but panic surged through my body. I believed this was my final moment on earth.

They say your life passes through your mind when you are about to die, and I suppose it's true – all I thought about was my wife and children, and how they are my life. Here I was, thousands of miles away from home in Macduff in the North East of Scotland, caught up in a major terrorist event in Mumbai. This Indian hotel was not the place I wanted to die.

This experience has given me a different perspective. I will never again take comfort and an easy existence for granted; I now fully appreciate the importance of family, friends and loyal work colleagues. In the West, it's all too easy to put out of our minds the vast gulf between rich and poor, how the world of the 'haves' is so starkly paralleled by that of the 'have-nots'. Most of my working life I was oblivious to this parallel world. I had my wake-up call in November 2008. Working for the Royal Bank of Scotland, I was on a second business trip to India where I was helping to set up a new operation. I was fortunate to survive one of the most audacious terrorist attacks in recent times.

My story is a personal one. I'm not a politician, a media celebrity or even a senior bank director, but I have been encouraged to tell my true story. It is how I became caught up in the Mumbai massacres, and witnessed the slaughter of innocent people who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.

For over 40 hours, I was a hostage in a burning hotel while a group of suicidal terrorists – who had already murdered hotel workers and guests in cold blood – remained barricaded in with hostages on the floor directly above me.

As the machine gun fire, rifle bullets, grenades and a bomb crumped into the building, I was kept alive by my Blackberry contact with the outside world, especially my amazing Royal Bank colleagues back in the Edinburgh headquarters. As the intensity of the gunfire and grenade attacks increased, I concluded that it was unlikely that I would survive. I thought of Irene, my wife, and my children, Lisa, Christopher and Stephanie, and all the things I'd never said to them. I also thought of my poor parents, who would hear of my violent death – and how this would rekindle the pain of the loss of my brother, Christopher, who died, a 16-year-old deck hand, in a Highland fishing boat disaster in December 1985.

Many people will recall the horror of the picture of the 'Man Who Jumped' after the September 11 atrocities in the United States in 2001. The man falling from the north tower of the burning World Trade Centre in New York was an image I could not erase from my brain as I trembled in that blackened hotel room. It was this horrific image that prevented me from jumping. As I contemplated my own fate, a powerful, almost primal, instinct to survive kicked in. Somehow I discovered a clarity and calmness of thinking which helped me make the right decisions under extreme pressure. This, coupled with luck – or perhaps fate – meant I survived to tell the tale, where so many others perished.

CHAPTER TWO

Finding My Anchor

TO UNDERSTAND WHAT I mean about parallel lives, I think it's important to know about my own upbringing and what has moulded and shaped me. My early years were pretty normal, although, as I will explain later, there was some terrible family grief that we had to come to terms with. I was born in Banff, on the North East coast of Scotland, on 10 March 1966. The rugged Moray Firth coastline weaves west to east along from Buckie to Fraserburgh and then turns down south to Peterhead. Along this North Sea coast are a string of fishing communities, including Whitehills, where I lived as a youngster, and my own home town of Macduff. To this day, it's an area that places a great deal of store in the value of ordinary people and community, and the hard work of honest folk.

My dad, also called Roger, worked in the building trade, and when I was about three we moved to Glenrothes. It was a new town in Fife and there was the promise of more work and opportunity. But the pull of the North East of Scotland was always too much for the family. One night, when I was ten, we packed all our belongings in a car and moved back to Whitehills.

I left behind some Fife chums without saying goodbye that I never saw again, although years later I looked up some of them. I went to Fordyce Primary School until I was 12 and worked hard as a student, as I was ambitious from a young age.

At school we were all fanatical about football. I played almost every day and was fairly good but never had the build to be a strong player. But my brothers and I loved going to the big games and especially to Aberdeen FC – the Dons – who played at Pittodrie Stadium 45 miles away. I was the eldest of four children and from 12 years of age onwards, when I went to secondary school, Raymond, Christopher and myself would go on the bus to the home games at Pittodrie to watch one of the greatest teams that has emerged from Scottish football. My sister, Lynne, wasn't so fanatical on football.

For a few seasons we never missed a home match: it was an amazing team. With my dad struggling to find good employment our family wasn't well off, so I had to find a job. I started as a delivery boy on a milk round with Robertson's dairy in Macduff.

Winter mornings in the North East are often icy and dark. My work began at 5am, so I pulled on my warmest clothes, scarf, jacket and boots. Fred, the regular milk van driver, would pick me up. He was always right on time and I came to admire his cheery disposition and his ability to get up on the darkest and coldest mornings – even when the milk bottles were frozen – and do the job. It all seemed so much safer and more trustworthy then. At many of the houses where we delivered the milk, the residents were still asleep. They would leave the weekly money on a table or in a kitchen drawer. I used to tip-toe in, take the cash, and leave the milk with the household still slumbering.

Most of the major events in my teenage life revolved around Saturday nights out with my mates in Macduff, Banff and Whitehills and travelling to watch 'The Fabulous Dons'. In 1982, Aberdeen were playing in the preliminary rounds of the European Cup Winners' Cup. It was an amazing evening and the Dons ran out winners 7–0 against FC Sion of Switzerland. Little did any of us know about what was to come.

Under manager Alex Ferguson, 'Fergie', the Dons were the best Scottish football team of that era, better even than the 'Old Firm' of Glasgow Celtic and Rangers. Aberdeen won the Scottish League championship twice and the Scottish Cup three times, in 1982, 1983 and 1984. The whole team was packed with legends: Jim Leighton, Doug Rougvie, Alex McLeish, Peter Weir, John McMaster, Willie Miller, Gordon Strachan, Ian Scanlon, Steve Archibald, Mark McGhee, Neil Simpson, John Hewitt, Eric Black and Neale Cooper: every one was a hero to me.

They were a brilliant team with an amazing attitude. This was infectious and we loved being part of the Red Army of supporters who shouted, cheered and sang for our team. The bus from the Banff branch of the Aberdeen FC Supporters' Club would leave the town at 11am and drop us off at the Bobbin Mill pub in King Street. The older guys would go for a lager or two while we'd walk to the ground. Such was the clamour to see this great side, if you didn't have a season ticket, you simply didn't get in.

Fergie was the boss and he was still learning his trade as a football coach. Over the years in my professional life I have come to admire Sir Alex, the Manchester United boss since 1986, as a supreme coach. He knows how to mould and motivate a group of thoroughbred and often wayward young people and allow them to perform at their optimum level. His motto of: Never Say Die, Never Give Up has been inspirational to me.

Working alongside Fred the milkman instilled in me a work ethic, and watching the Dons in the 1980s taught me about the value of team-work – and since then I've often thought sporting achievement and success remains a powerful metaphor for life as well as business. I still think business can learn a lot from examining the very best sporting coaches.

I worked hard at school, although I wasn't a swot. I was dux (top of the academic class) at Fordyce Primary and was made a prefect at Banff Academy. I had an idea that I wanted to be a lawyer. I took six Highers in fifth year and gained the qualifications to get into Aberdeen, Edinburgh or Glasgow universities. But the reality of coming from a working-class background struck home. I knew it wasn't financially viable for me to go to university, and it was better to go and find a job.

When I was 15 I started seeing a local girl called Irene, who was attractive and rather shy, but very neat and well organised. Her dad was a hugely charismatic fishing skipper who had two boats that went out to fish from Macduff. The fishing is embedded into the life of the North East coast. It's an extremely harsh and dangerous way to eke out a living. For Radio Four listeners tucked up in the bedrooms of our big cities the names listed on the Met Office shipping forecast – Viking, North Utsire, South Utsire, Forties, Cromarty, etc – might seem an irrelevance; but these forecasts were of vital practical use for our fishermen, whose voyages took them to Bailey, Hebrides, Fair Isle, south Iceland and far out into the storm-lashed Atlantic. Between 1961 and 1980 there were 909 recorded deaths at sea involving fishermen. The weather and the conditions at sea are a daily topic of conversation in fishing communities and every time the boats go to sea, there are fears in the back of the mind of all left on shore.

While I wanted to start working, I didn't really want to go to sea. So I sent my CV and a covering letter to a number of banks who were looking for school leavers and I was accepted by the Trustee Savings Bank group, later Lloyds TSB, and also by the Royal Bank of Scotland. I took the Royal Bank job because it offered better prospects. It was a decision which gave me nearly 26 good years as a banker.

On Wednesday 11 May 1983, Aberdeen won the European Cup Winners' Cup, beating Real Madrid 2–1 in Gothenburg. Eric Black opened the scoring while the Spaniards equalised with a penalty. The game went to extra time and John Hewitt scored the winner. The whole of the North East of Scotland went wild. The returning heroes celebrated in an open-top bus along Aberdeen's Union Street. It was an epic summer in the North East.

What a good year that was for me. On 18 July 1983, aged 17, I began my career in banking. I was told to report to the training centre in Kilgraston Road, the Grange, in the leafy south side of Edinburgh. It was the first time I'd been away from home on my own. The bank seemed very formal, partly because of its awesome tradition. The Royal Bank of Scotland was founded in 1727, some years after the Bank of Scotland was set up in 1695. Scottish bankers were admired internationally for the acumen and prudence with which they looked after people's money.

I was sent back to work in the Banff branch of the Royal Bank of Scotland. It was all rather repetitive. We counted cheques and cash every night, to ensure that not a penny was missing, and often we'd be there long after closing time to ensure that the books were balanced. Banking hours were 9.30am until 3.30pm, but if there was a mistake we might not get out until nearer 6pm. I wasn't really sure that this was what I wanted to do, so I applied to the police force. I went to Elgin and sat the entrance exam, which I passed, and then I went for a medical at Bucksburn regional headquarters in Aberdeen. During the sight test the doctor asked me to read the letters on the top line of the eye-chart. It was like one of those classic comedy moments. I couldn't even see the chart, never mind the actual letters.

'I'm sorry, I can't read anything,' I said. 'Well, thank you, that will be all,' the doctor replied. The 30 seconds it took to do that test put paid to any idea I had of joining the police and made me reconsider what I had to do to further my career in the bank.

Most of my pals had gone straight into the fishing when they left school. My salary in the bank was about £50 a week. A 16-year-old returning from a week at sea could end up with £350 in his hand. I began to wonder who the daft one was. So when Irene's dad offered to take me out to sea, I went out on his boat, the Crystal Waters, a pair trawler with his son John's boat, the Crystal Sea: they would fish with nets slung between the two vessels. The weather wasn't too bad but it was rough enough to make me sick for most of the time. It was a miserable existence standing below deck, gutting cod, haddock, lemon sole and plaice, pouring ice over them and piling up the crates. My fingers were cracked and sore with the bitter cold. The stench of diesel fumes and the constant rocking of the trawler made it very uncomfortable. I'm proud of the North East's trawling heritage and how it binds the communities, but I finished up after this first trip, and, despite the lure of the ready cash, decided that the fishing wasn't for me.

By now, Irene was becoming a major part of my life – and to this day she has remained my single biggest inspiration. She encouraged me to progress with banking, accelerate my training and sit my banking exams. Her dad and mum were also supportive of my decision to pursue banking more seriously as a career. When we were 18 we got engaged and started to save up for our future. She has been the anchor in my life – an appropriate description coming from a seafaring family. Over the years we have done everything together and have been proud of raising our three children: Lisa, Christopher and Stephanie.

In 1984 I was moved to the Fraserburgh branch of the Royal Bank of Scotland. Fraserburgh, known as 'the Broch', was still one of the UK's biggest fishing ports. When the fleet returned with its haul of cod and haddock there was plenty of cash to throw around, and this bank branch was a great place to learn a bit more about real business. From boat financing to asset management, the branch was always busy with customers. There were bills to pay for oil and provisions at sea, new nets or radar kit. The fishing rebates all came in around Christmas with hundreds of thousands of pounds changing hands in the North East.

I had passed my driving test when I was 17 but I still couldn't afford a car. That would have to wait. And because there was no regular bus service from Whitehills to the Broch, I moved into a room rented from a wonderful woman in her 60s called Jean Webster, who worked in Webster's Bakery, on North Street. She lived with her sister, Anne Harrison, and her husband. They were all deeply religious people, closely connected with the Fishermen's Mission, the Christian society which looks after those fisherfolk who have fallen on hard times, or simply need a warm place to stay after a trip to sea. I was expected to observe the house rules, but I think Jean and Annie enjoyed having a young banker living with them. It gave them some kudos to talk about the young 'loon' from the Royal Bank.

My rent was £12 a week, and this was extremely good value because I had about half of Jean's house. And there was another bonus: Webster's Bakery made the best cakes, baps (morning rolls) and butteries (known as rowies) in the Broch. Every Monday night when I'd returned for the week, Jean would knock on the door and give me several bags of baked goodies, which lasted me the week. It was a wonderful place to stay for a while; but I was young and full of ambition.

Three months before I married Irene, I was transferred to Peterhead, then still one the UK's busiest fishing harbours and also a port used by the developing offshore oil and gas industries. My mentor was the senior branch manager, a great guy called Bill Nicol. Bill had a heart of gold. He was an unorthodox fellow, always immaculately turned out in pinstripe suit, tie and braces. A real grafter who instilled in me the importance of doing things properly, he was a stickler for getting it absolutely right – first time. He inculcated an ethic of hard work, trust and honesty in all of us.

Bill, a keen golfer, lived in Aberdeen and travelled up during the week to the branch. I remember him hobbling out of the office with a bad leg one Saturday afternoon before going back home; over that weekend, he had a heart attack and died on the golf course. It was huge loss to the bank.

I've worked with hundreds of talented people but Bill remained my litmus test for what was right. Throughout my career I often asked myself: How would Bill have done this? What would Bill say about that?

CHAPTER THREE

Losing a Brother at Sea

TRAGEDY VISITED MY FAMILY on 20 December 1985. My 16-year-old brother Christopher was working as a deck hand on the MFV Bon Ami (BF 323) the night it foundered on rocks known as Minister's Point, just a few hundred metres short of the entrance to Kinlochbervie harbour.

That evening had been particularly stormy with the wind bitter and heavy snow falling well into the evening. On such nights I often thought about my brother being out at sea. With Irene's side of the family so heavily involved in the fishing industry and most of my school friends now at the fishing, I was so familiar with that way of life that I never had any real fears for his safety. Perhaps it's superstitious – many people who make their living by fishing are that way. And after all, Christopher was berthed with a skipper who had years of experience and was very well respected in the community. If anything, it seemed as if Christopher had pretty much landed on his feet in securing a position on the Bon Ami. I had visions of him making lots of money, driving a sporty car and buying expensive gifts at birthdays, Christmas and anniversaries.

Christopher had initially been given his chance in the summer of 1985 on the sister boat, the Bon Accord, owned by the same skipper, and had enjoyed his early months at the fishing. Although on an apprentice's wage, the money he was making was reasonable given that he was still at home with my mum and dad. When I returned home from Fraserburgh at weekends, you could often find him in the Cutty Sark, one of two pubs in Whitehills, where he loved to play pool, and on many occasions picked up a trophy or prize money for his efforts. Strictly speaking he shouldn't have been allowed in because he was only 16 at the time.

It was commonplace for fishing boats to have a number of relatives aboard the same vessel, which was ideal for many families when the fishing was going well. But the other side of the coin was the loss of several members of a single family when a tragedy occurred. Christopher had worked really well on the Bon Accord and was good friends with the skipper's son, who was berthed on the Bon Ami. Then before Christmas, the skipper made the decision to swap the lads and put Christopher onto his boat.