Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Grosvenor House Publishing

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

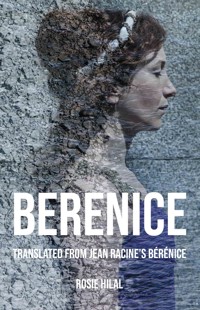

Berenice is an academically rigorous, poetically sensitive and politically hard-hitting translation of Jean Racine's celebrated 17th century tragedy. An adapted version of her text with movement was first staged in 2018 in a co-production between Theatre Forge and Exchange Theatre as part of Voila! Europe theatre festival under the title Becoming Berenice with original drum and bass music by Tomas Wolstenholme to sold-out audiences. Unusually retaining the original French structure of rhyming 12-beat couplets, or Alexandrines, this modern English version seeks to highlight the Western colonial expansion in the Middle-East against which the story plays out, and of which we are arguably reaping the ever more violent repercussions. This tale of one woman's emancipation in the face of star-crossed love is the first English translation of this European classic by a woman and a person of Middle-Eastern descent.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 96

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

DEDICATION

To my parents and grandparents, for their eternal support and loving care.

CONTENTS

DEDICATION

FOREWORD

PREFACE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A NOTE ON ALEXANDRINE VERSE

BERENICE – CHARACTER LIST

BERENICE – ACT 1

BERENICE – ACT 2

BERENICE – ACT 3

BERENICE – ACT 4

BERENICE – ACT 5

QUOTES FROM READERS AND AUDIENCE MEMBERS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

COPYRIGHT

FOREWORD

Rosie Hilal breathes fresh life into this play with her verse translation into English, part of her wider project of rejuvenating the iconic work both on page and stage. Whilst this Racinian tragedy is well known in France, Anglophone audiences are undoubtedly less familiar with this story of forbidden love and sacrifice.

I first met Hilal during a rehearsed reading of this play organised by the Open University’s Gender and Otherness in the Humanities research group in 2023. She herself was performing the role of Berenice opposite David Furlong, artistic director of bilingual French/English theatre company, Exchange Theatre.

The powerful presence of the eponymous character is showcased in Hilal’s ambitious text. Her translation will help this complex play – in which love, duty and politics intersect – reach wider audiences. The exploitation, ‘othering’ and fear of the Jewish-Palestinian princess Berenice, exhibited by the Roman characters in the play, will resonate in thought-provoking ways for new generations.

Hilal wrestles with the themes of gender, otherness and colonial power embedded in the text and demonstrates her close attention to and appreciation of Racine’s original language and verse form. As a Cambridge-educated linguist and RADA-trained actor experienced in the use of verse and classical text as well as new writing, Rosie Hilal has skilfully woven a contemporary, speakable version which nonetheless strives to stay loyal to the original text in both content and structure. The unflinching language with which she renders the violent imagery already present in Racine’s text, further highlights the political background of the play. Hilal has identified that with this text we might draw parallels to the ruthless arms trades, genocides, and global colonisation today.

Hilal’s vibrant translation of Racine’s complex language is a valuable resource for students of French literature and lovers of theatre alike, making this an exciting rediscovery of an important play.

Dr. Emilia Wilton-Godberfforde

Specialist in seventeenth-century French (Fellow and Director of Studies (Corpus Christi), Senior Outreach Coordinator, MMLL, University of Cambridge)

PREFACE

I first encountered Racine’s work as a drama student in Paris. A classmate and I had been tasked to perform some of it in front of our terrifying teacher at the Conservatoire du 16ième arrondissement. I was ‘the English girl’ and new to the serious, French way of approaching theatre. When we haltingly performed our scene, our teacher told us to leave the stage and come back when we had ‘done the work’. Nevertheless, this first encounter with the beauty and powerful regularity of the Alexandrine rhythm, which characterises Racine’s texts, were enough to leave me hooked on this play for nearly two decades.

I was in love with a French actor at the time, after a series of tumultuous relationships I’d experienced as a teenager. I was aware of the difficulties of living in a culture that wasn’t my own, having grown up in Germany to Turkish and British parents and of course now, as a foreign student. Berenice’s delayed emancipation felt like a wake-up call to my soul which forever felt pulled in multiple directions; she inspired me to be brave. Not to let other people define me or determine the pathway of my life. To take control of my destiny. To keep my dignity. And never to bow down. Our 2018 Festival adaptation was titled Becoming Berenice to indicate the character’s emancipation at the end.

Originally, I translated the play in the hopes of re-telling a passionate love-story (which is what Bérénice is primarily known for) and spreading my love of Racine with the Anglophone world. But in doing so, the darker themes became apparent: at the start of the play Arsace, the comedy side-kick to his tragic master Antiochus, enumerates the reasons why his Middle-Eastern master should take all he can from Rome: the Empire stole his crown, his power and his independence, the least he can do is to wait for them to reward him richly for his forced services to the state. Arsace’s almost incidental description of the brutal quelling by the Romans of the Jewish uprising in 67 AD evokes the global history of European violence in African countries, India, North and South America. It mirrors the present-day expulsion of Palestinians from the West Bank and the current genocide perpetrated by Israel in GAZA. With every bomb that falls, colonisation seems more and more set in stone, and this 400-year-old text describes this horrific human habit in timeless, graphic detail.

Once I realised this, the urgency to put on this play transcended my wish to ‘make some work for myself’. I mobilised an international team of creatives and actors who had a personal understanding of the themes in this play: racism, classism, oppression – ‘othering’ for the sake of better controlling others. We staged an adapted version of the play under the more dynamic working title Becoming Berenice within the context of the 2018 Voilà Theatre Festival in London. People from all walks of life and the four corners of the earth crowded in, until people were standing around the edge of the space, because the themes and the music resonated with so many.

When you read this text I want you to imagine the musical soundscape skilfully woven by my friend and colleague, actor-composer Tomas Wolstenholme: electronic music and drum & bass sounds clash and combine with soulful, acoustic middle-eastern melodies, representing cold, harsh army forces clashing with the souls of countries – their culture. You might like to reimagine some scenes replaced by contemporary dance; we did this in our performance to shorten the play and to underline the visceral nature of the text and the story. I believe when it is well spoken this text can conjure all this without music, but for a global, contemporary audience the show could work on multiple sensory levels to increase the effectiveness of the message in this play: don’t kill each other for states that show no mercy. Love and respect each other instead.

Rosie Hilal, London 2024

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to thank all those who have helped and encouraged me with this translation project: my strict but brilliant teacher at the 16ème de Paris, Stéphane Auvray-Nauroy, who introduced me to Racine’s work and taught me how to speak Alexandrines; my French boyfriend at the time, the actor Barthélémy Meridjen, who put up with my obsession and rehearsed with me; my mentor at Morley College Playwriting Course, Phil Morris, who helped kickstart my translation; my partner Mike, family and friends who supported me in a myriad of ways as I wrote; Lloyd Trott, Jo Wiltshire, Mel Jessop and the RADA graduate development team; all the exquisite actors who workshopped my translation with me*; the cast and creative team of the 2018 staged version titled Becoming Berenice, especially composer Tomas Wolstenholme**; the VoilàTheatre Festival team; my friend and director David Furlong and the team at Exchange Theatre; Professor Nick Hammond, Dr. Emma Gilby and Dr. Emilia Wilton-Godberfforde of the University of Cambridge French Department for their feedback, advocacy and support; every single audience member who has already seen it, and all those who still will; and to you, the reader, thank you for trusting me.

*Actors who gave me their time & talent to workshop Becoming Berenice:

Lucy Sheen, Gary Merry, Sadie Leyla Clark, Issy Brazier-Jones, Jordan Mifsud, Vivienne Gibbs, Will Wolfe-Hogan, Imogen Daines, Pia de la Borde, Olivia Vinall, Alex Guelff, Sarah Kenny, Sarah Twomey, Rebecca Scroggs, Matteo Franco, Pali Nall, Felicity Davidson, Cindy-Jane Armbruster (also premiered), Jenn Kay (also movement director), Kai Hœgenacker (also intern), Amber Savva (also production assistant)

**2018 cast and creative team of Becoming Berenice:

Rosie Hilal – Berenice

Cindy-Jane Armbruster – Phenice

Matteo France – Antiochus

Ariane Barnes – Arsace

Sam Lawrence – Titus

Amanda Maud – Paulin

David Furlong – Co-Director

Fanny Dulin – Co-Producer

Tomas Wolstenholme – Composer

Jennifer Kay – Movement

José Triguero – Choreography

Berta Pibernat – Lighting

Inès Hatchou – trailer and ‘making-of’

Charlie Baptist – Costume Design

Kyla La Grange – hair & make-up

Katherine Leedale – Photographer/Images

For more details about the artists, links to the trailer and mini-documentary, audience feedback and the original music, visit: www.theatreforge.com / www.rosiehilal.com

A NOTE ON ALEXANDRINE VERSE

Though not an academic specialist in Alexandrine verse, or indeed any other type of verse, I have much practical experience of performing a variety, in French, English and Spanish. I love the power, the structure, the inevitable forward motion, which can be broken if one so chooses, but is always there as a point of departure, a solid arm to lean on. As a performer, it is a gift; as a reader, it can be, too.

The general rule for French Alexandrines is that each line should be 12 syllables long. I have endeavoured to write my English version in such a way that if pronounced naturally, one should always have 12 syllables per line. They also (mostly) rhyme.

Halfway through each line of French Alexandrine, you will find a natural break, both in sense and breath, at the six syllable mark; this is aptly named a ‘caesura’. This means you only have to get your head round the first six syllables, then you have a second to compose yourself and unknot your tongue, before you read the second half.

Sometimes however, English grammar lends itself more to the line being divided in 3 parts, like a triplet in music. If you think of this text as a musical score, with recurring themes, a regular, baroque pattern and each line being equivalent to a bar, divisible in 2, 3 or 4, then it rolls off the tongue more easily. If you can’t read music, don’t worry, you just need to be able to count to twelve.

In the spirit of preserving the very essence of ‘French-ness’, I chose to keep the 4 most famous lines of verse in the original language. It is a phrase that even French people who have never seen or read Bérénice will often recognise. It is as iconic as Juliet’s ‘Gallop apace’ or possibly even Hamlet’s most infamous line.

As an actor I love the challenge of making verse sound off-the-cuff, and I hope my mix of contemporary and timeless vocabulary as well as a shorter sentence structure will make this easy. When reading this text remember passion and humour; verse needs to be supported by true emotion, otherwise it falls into the trap of sounding ‘old-fashioned’.

I trust you will enjoy reading and I look forward to being invited to your performances!

Rosie Hilal, London 2024

BERENICE

BERENICE

CHARACTERS

BERENICE – 40s, female. A Judean/Palestinian queen, Titus’ lover. Has been ruling Rome alongside him, currently unmarried.

TITUS – 20s, male. A young Roman general, son of the late Emperor.

ANTIOCHUS – 30s, male. A Syrian Prince, forced to fight as a soldier for the Roman Empire.

PHENICE – any age, any gender. A Lebanese slave, spoil of Rome, serves Berenice. Speaks little but listens a lot.

PAULIN – 50s/60s, any gender. The late Emperor’s trusted advisor, now advises Titus.

ARSACE* – any age, any gender. Iranian or Armenian bondsman and foot-soldier. Serves Antiochus. Similar to a Shakespearean fool.

RUTILE –