8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

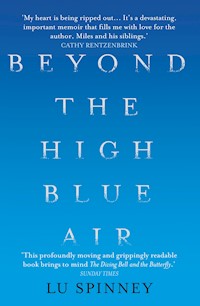

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Aged 29, Lu Spinney's son Miles suffered a devastating head injury and was left in a coma. With unflinching honesty, Lu Spinney has written a passionate, urgent account of the years following her son Miles's accident, revealing his existence imprisoned in a limbo of fluctuating consciousness, at times agonizingly aware of his predicament. With unfailing honesty and courageous prose, Lu Spinney's memoir explores the very nature of self and the anguish of witnessing Miles's suffering as she and her family come to realise that, although he has been saved from death, he has not been brought back to a meaningful life.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

For everything begins with consciousness and nothing is worth anything except through it.

Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus

But to have been

this once, completely, even if only once:

to have been at one with the earth, seems beyond

undoing.

Rainer Maria Rilke, ‘Ninth Duino Elegy’

MILES KEMP

Contents

19 March 2006 – St Anton

19 March 2006 – London

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

Acknowledgements

Author’s Note

19 March 2006 – St Anton

Imagine a young man in his prime. He is quite tall, has clear, deep green eyes, brown hair thick and so dark it can gleam almost to black, and a longish face balanced by strongly defined cheekbones and jawline. His look is humorous, challenging, engaged; there is a vivid charge of energy to be felt in his presence. He has just turned twenty-nine and after a week’s hard snowboarding he is fitter than ever; that is the reason he will be known by the doctors and nurses in the Intensive Care Unit as The Athlete.

It is early morning on the last day of his skiing holiday and the sun is just beginning to glint and sparkle on the night-hardened snow. Inside his room it is still dark and he will have had to set an alarm to wake this early, for early rising is not his forte. There is that particular hush in the air that comes after a night of heavy snow, broken now only by the distant sound of the piste machines with their wide corrugated tyres already busy preparing the empty ski slopes. Turning off the alarm, the young man lies back luxuriously in his bed to contemplate the day. Tomorrow he will be back in London and back to work, and he realises with surprise that it’s not an unpleasant thought. In fact, there is nothing right now that he doesn’t feel positive about, a state of mind he used to associate only with childhood. His school years were not straightforward and in his early twenties his bent for introspection descended into a suffocating depression, during which he came to recognise the hard-eyed gremlin sitting on his shoulder overseeing his every move, judging, criticising, never drawing breath. ‘The rabid prattle in my skull,’ he once wrote. But over these last few years the prattle has subsided and now it is gone; his mind feels as sharp as a new razor, his sight is clear. If you asked him, he would admit he feels capable of achieving great things. Indeed, he is anticipating it; in an attempt to clarify his aims he has written in his journal:

Step back. What are the principles?

Don’t want to abstract. Want to create.

Want to create things of great beauty and power.

Want to change the world.

He sees his future brightly lit and gleaming ahead of him. Having reached that point where ambition and self-awareness happily coincide, he now acknowledges his weaknesses and knows his strengths. With exhilaration he feels that anything and everything is possible.

He gets up and draws back the curtains, letting sunshine cascade into the room against a backdrop of snowy mountains and blinding blue sky. With a prickle of adrenalin he remembers the day’s plan – last night he and his friends had decided they couldn’t leave without attempting the notoriously high jump in the snowboard park that they hadn’t yet tried. For the first time in all his years of chasing the thrills of skiing and snowboarding he is going to get himself a crash helmet. That is why he has to get up early today, to give himself time to go to the ski shop where he will buy the best one available; he likes the best of things and now he can afford to be extravagant.

He packs his small bag, throwing in his clothes without a thought, no careful folding or smoothing. Then he takes a quick shower, long enough to enjoy the sting of hot water washing off the suds as he feels the tension in his muscles; keeping fit is one of his hobbies, which is why he has taken up amateur boxing back in London. This reminds him of a former girlfriend, Annabel, and he thinks now with pleasure about her body, as lean and supple as a ballerina’s even though exercise was as alien to her as ballet is to him. Together with his mother and sisters, it was she who nagged him to give up boxing when he came home one evening from his weekly bout with his tee shirt covered in blood. You have such a magnificent brain, Annabel had said, it’s one of the things I love about you! He considered giving in to them, for in a rueful sort of way he enjoyed the fuss they made.

Breakfast is served downstairs in the small dining room of this old Alpine hotel with its checked gingham curtains and cosy decor, everything so strangely diminutive compared to the view through the mullioned windows. When I have a chalet in the mountains, he thinks, I’ll have one built to amplify the light and the vastness, to feel on the edge of such awesome beauty and to see and know it is dropping away beneath me. Soon he is joined for breakfast by his friends, Ben and Charlie, both fellow snowboarders as well as colleagues back in London, and after some laughter recalling last night’s exploits they confirm the day’s plans. The snowboard park, the jump and then the dash to the airport to get the flight to London. They discuss the jump, how long the descent for it should be, where to start; it is difficult to judge at what point and at what speed it should be taken to remain on balance, which is where the thrill comes in. The longer the approach down to it, the faster you go, the higher you jump. He is the only one not to own a helmet so he leaves them finishing breakfast and makes his way to the ski shop.

This is St Anton and the shop is appropriately stocked. The clientele of the elegant resort are a mix of ambitious snowboarders and well-heeled classical skiers and there is every fashionable accoutrement for sale. He is distracted on entering by a striking girl assessing herself in a long mirror, clearly wondering about the figure-hugging pale turquoise ski suit she is trying on. He catches her eye as he walks past and wants to say, You look beautiful in that, but he doesn’t and fleetingly regrets his reserve. Soon she is forgotten and he is looking at helmets, listening carefully to the laid-back long-haired ski pro describing the merits of each. Trying them on he is surprised by their lightness but dislikes the sensation of containment. He wonders if it might be disorienting; absolute concentration and precise balance are needed when making a serious jump and the helmet could be a distraction when he is not used to it. The assistant explains the technology and shows him how the fit must be precise, the strap under the chin tightened and adjusted just so to keep it in place. And of course it needs to look cool, because undoubtedly part of the fun of snowboarding is looking cool, which he can’t help thinking is compromised by a helmet. But the jump today is very high and he is going to take it as hard and as fast as he can, so this precaution is the responsible thing to do. As he pays for the sleek black choice he’s made he senses the familiar excitement beginning to build. Picking up his snowboard as he leaves he feels an added surge of pleasure; he bought it while in the States a few months ago and he hasn’t yet seen one like it here. There’s nothing to match its curled smoothness and sleek design, not even in the racks of gleaming new boards in this shop.

Out in the sunshine he puts on his sunglasses and looks around. There is a photograph of him taken at this moment by one of the friends who has just arrived, so imagination is not necessary here: he doesn’t know it but he is as handsome as he might ever wish to be, and the girl also caught on camera coming out of the shop in her new turquoise ski suit thinks so too as she gives him an inviting smile. He doesn’t notice, for all he is interested in now is the perfection of the moment: even down here at resort level he can see the snow is still thick from last night’s fall, so he knows the slopes higher up will be ideal for snowboarders, the thin cool air just warmed enough to be comfortable for working up a sweat. If they get cracking they might have time after the jump for a quick sandwich and a beer in the sunshine before they leave. He zips up his jacket, puts on his padded gloves and casually tucks the snowboard under his arm as he walks with his friend across to the chair lift.

Arriving at the top he thrills to the view spread before him. Pushing himself off the chair lift, he slides across to the edge and stands quietly for a moment, taking it in. It is the thrill of being on the tip of the world, snow-covered peaks in every direction fading into the blue distance, the sense of latent power brooding within the vastness. To be made aware of his insignificance in the face of nature’s grandeur but to know he is an essential part of it too; he remembers when he first thought about it in that way, a small boy talking to his mother as they sat together on the balcony of their Alpine chalet, how grown-up he felt when she took his discovery seriously.

He can hear his friends have all arrived, so he turns back from the view to join them. Together they set off towards the snowboard park, moving down in unison over the freshly fallen snow.

And now he is standing at the top of a slope that leads in one steep drop to the dip and rise of the jump, a curved tusk of packed snow protruding out of the whiteness. It looks huge even from this distance and he recognises the sudden blaze of mental clarity that accompanies adrenalin release. This is when he is at his happiest, under pressure, pushing himself to succeed. He likes the sense of breaking through ever more challenging barriers; he savours the private confirmation of his own worth. It is not conceit – depression and introspection have saved him from that; it is simply a clear conviction of his rootedness in the world, of the value of this existence, here and now, his intention to live his life to its limits.

He adjusts and fastens his new crash helmet as he was advised to by the ski pro. He checks the bindings on his snowboard; they’re working fine. He is ready to go. Adrenalin and excitement mixed with a sudden sharp twist of fear; he can smell the acrid whiff of his perspiration. Then, taking a deep breath, he pushes himself off and down the slope. At first gliding and swooping from side to side as sure as a hawk descending to its prey, his path gradually straightens into an arrow of gathering speed for the final descent towards the jump. Too fast now, he fears he could lose his balance and then he has reached the dip of the jump and he knows he is not in control as he is taken by force up the ramp, skewing sideways as his board clips the edge and then he is hurtling, spinning up, up into the free blue sky ahead . . .

The thwack of board and helmet on hard ice, the cries of onlookers, the blue of sky and white of snow. Silence. Then, very slowly, the fallen figure sits up, raises himself, stands shakily. Friends gather round, supporting him, their faces grave. After such a fall how can he be all right? He speaks: Jesus, that was something. So shocking was the fall that someone feels it necessary to ask him, Do you know where you are? Do you know what day it is? St Anton, Sunday, he says, thickly. He takes off his helmet and slowly pushes himself on his board to the edge of the slope and sits down. Motionless, head bowed, and then, suddenly, violently, he vomits onto the clean white snow. The friends’ faces now in horror, watching as his eyes roll upwards and his body convulses in front of them all, back arched, limbs juddering. A doctor skiing past stops to help, the Rescue Patrol is called, paramedics are removing the young man’s jacket, tee shirt, cutting through his vest in the race to keep him alive, the air reverberating with the thump, thump of a helicopter’s blades . . .

In the helicopter the young man stops breathing. Below him the mountains glitter impassively in the slanting afternoon sun as he dies, for a moment. But the two paramedics immediately put their skills to work, passing a tube down his throat and connecting the other end to a portable ventilator. He is made to breathe again; he has been prevented from dying, but he is still critically injured. The neurosurgery team at Innsbruck University Hospital have been warned that he is coming, it is a Sunday so the on-duty surgeons are called from their homes and when the helicopter lands on the rooftop landing pad and the young man is whisked down to the operating theatre they are ready, waiting for him. Without their skills he would have died again, his brain bleeding and swelling, lethally compressing his brainstem, but they are excellent and dedicated neurosurgeons and for the second time in three hours his life is saved.

19 March 2006 – London

Happiness complete: a Sunday morning in early spring, pale shafts of sunshine falling through the gap where the bedroom curtains don’t quite meet and I lie in bed thinking, Ron is right. He says I wake easily, like a cat, and that is how I feel right now, the languorous contentment of a cat. The sun is shining and it’s a Sunday so Ron will be at home all day, Claudia and Marina are still asleep upstairs after getting back from university yesterday, Miles returns this afternoon and Will is coming home for supper tonight. Added pleasure from the relief in remembering that Miles won’t be snowboarding today, he won’t have time because he’ll be travelling to the airport and that means his holiday is safely over. I can feel the background fear of the past week dissolving, the fear that always lurks when Miles or Will are away snowboarding. I’ve seen them both doing those jumps and it doesn’t bear thinking about.

Turning over lazily I find Ron is already awake, sitting up next to me reading. How gorgeous is the morning, I say, and he blows me a kiss, continuing to read. Like Miles, he’s undistractable when reading, but I continue anyway. I’ve been lying here feeling ridiculously contented, Ronathan, I tell him. It’s all your fault. It’s true; how many times have the children and I talked about the happiness Ron has brought, of a kind none of us could have dreamed of during the long, painful unravelling of my marriage to their father. Meeting Ron six months afterwards was for me, still exhausted and diminished from the divorce process, like suddenly being swept up by a giant wave at the end of a tumultuous storm and then being brought in to land somewhere far away, unfamiliar but safe. The weird thing is, I continue, even if he isn’t really listening, that this happiness feels fragile at times. Little slivers of dread that it’s too good to be true. Anyway, guess what, it is true right now. I distract his reading further with a quick kiss on the cheek as I get out of bed. I’d like another one of those, he says, putting down his book, so I stay a little longer in the warmth beside him. But we’ve got all these people coming for lunch, Ronathan, I remind him, so we should really get up and get going.

Since all the children will be home for supper tonight I asked the butcher for an extra large piece of beef to cook for lunch. That way I’ll have enough for dinner too – cold peppered beef with rosemary and anchovy aioli is their favourite and it will be a celebration tonight, all four being home at once. The best of all dinner parties, I think. If Ron doesn’t want a repeat of lunch I’ll do a treat for him too, maybe a creamy gratin dauphinoise, one of his favourites that now has to be rationed to keep his cholesterol down. It always seems to me a luxury rather than a burden to be the cook of the household, choosing what I want for each meal with the added pleasure of being able to gift what I cook. The rich trivia of domesticity, a sustaining thing, I think, as I crush the peppercorns in the heavy ceramic bowl, surprised afresh by the mouth-watering spicy scent from such a dull kitchen staple.

We prepare for lunch in a companionable duo. Ron has laid the table and is now sorting out the drinks. I found an interesting-looking bottle of whisky while I was down in the cellar, he says, one I haven’t tried yet. The boys and I can have fun tonight seeing what we make of it. I think now about Miles’s frank acknowledgement of the adjustment he had to make when Ron came into our lives. In the turmoil of my collapsing marriage with his father he had stepped right into the breach as the oldest child and provided, aged only twenty-one, a solid wall of support for me and his three younger siblings. It wasn’t easy for me when you first met Ron, he told me when we talked about it some time later, I had to make an adjustment, my role in the family changed. But he’s a top guy, Mum, the best thing that could have happened.

The main course is coming to an end, the ice-cream and caramelised oranges are ready and waiting and there is nothing left to do now except enjoy myself. When the phone rings I answer it in the kitchen and the background noise of people and laughter makes it difficult to hear the young man asking me if I am Miles’s mother. Yes, I reply, why, what’s happened? I know already, I know from the tone of the man’s voice even before I hear that Miles is gravely injured; later he will tell me the most harrowing moment of his life so far was being with Miles on the mountain slope as his body convulsed away from him into unconsciousness. I’m Ben, a friend of Miles’s, he says. He has had a serious accident on his snowboard. What injury? I ask, but again somehow I know. A head injury. He’s in an air ambulance now, on his way to Innsbruck University Hospital. Another friend and I are taking the train to Innsbruck to be there with him. I’m sorry, I have to go now, but I will call you again as soon as I get there.

The line clicks dead. I remain standing, frozen, still holding the phone to my ear, not daring to sever the thread that connects me across sea and forests and mountains to Miles, to the person who was with him at that fateful moment when I was not. From one instant to another the world has changed. We are no longer safe; with frightening clarity I see each one of the people I love as though standing on the edge of a precipice, isolated, friable, their outlines sharply etched above the abyss that now threatens us all. With what complacency have I existed before this moment.

My mind seems to have cut loose in a peculiar floating calm while my body absorbs the shock in a visceral plunge of nausea. Upstairs in the bathroom I study my reflection in the mirror with detached interest, as though peering through the window of a stranger’s house and seeing someone who looks faintly but interestingly familiar. Going back into the kitchen I’m still floating as in a dream, an out-of-body experience, watching myself as I put my hand up to stop the lunch party conversation. I’m so sorry, you’ll have to leave. Miles has had an accident snowboarding. A head injury. I can hear my voice, flat, expressionless, see Ron’s face as he stands up, the confusion and shock, and register the intake of breath as Jennifer, a psychiatrist, reveals something else in her expression of horror, a doctor’s knowledge.

Ron sees our guests out while in a distant land Ben and Charlie are travelling over the mountains to Miles. Above them a rescue helicopter (red I imagined, but now I’ve seen the photograph I know it was white) is taking Miles low over the same mountains towards the waiting surgeons. In the helicopter the sound of Miles breathing on the portable respirator as his brain is silently bleeding and swelling, the noise of the blades chopping the air outside, the Austrian paramedics talking in low tones (or shouting above the noise?) working to keep him alive while below them the snow-covered Alps gleam in the late afternoon sunshine. Too terrible to think of myself vainly crushing peppercorns at the moment that he stood, thrilling with adrenalin, on the top of that ski slope, unaware he was poised on the threshold of consciousness. He fell to earth and only his brain was hurt; from such a height and at such a speed that it shattered in the crash helmet like an egg in an empty biscuit tin, shearing the axons and damaging all those fragile, magnificent neurons. And not a bruise on the rest of his body – how can one make sense of that?

Late that Sunday night we too fly over the mountains, enduring the banter of the easyJet air hostess and the jovial passengers setting off on carefree holidays. The children’s father, David, has joined us and landing at midnight, blank with exhaustion, we hire a car and drive through the bleak streets beyond the airport to the first hotel we come across. It looks brutal, an unloved concrete façade punctuated by straight lines of barred identical windows. The foyer is too hot and the man behind the reception desk ominously relaxed, as if he has been expecting us to arrive here in this place at this time. He leads us to our rooms through stifling circular corridors, the air as stale as a tomb.

The Austrian surgeon we telephoned from London before we left had advised us to stop on our journey overnight. Get some rest before you arrive, he said, it would be better for you to come feeling fresh in the morning. We will take care of him. He sounded concerned and kindly and we had not questioned his advice, but now I wish we had. Rest is irrelevant and anyway impossible; the only imperative is to reach Miles.

Lying on my back on the hotel bed in Munich, the day’s events sift down slowly in my mind like the last silent ashes falling after an eruption. Everything lies colourless, shapeless, now coated in a thick layer of dread. Through the window above my bed a pale sliver of moon gleams coldly; it will be shining down on Miles too, I think, and I sense the first tremor of a strange new anger. I’ve known that moon since early childhood, growing up on a farm in Africa hundreds of miles from any city; most nights were as black as pitch, but when the moon was up it shone with a fierce beauty that dazzled the African darkness. Later, when we moved to live by the Indian Ocean, it gilded and soothed the waves with its ethereal light. I felt protected by this moon of mine, felt a private oneness with its ancient, soundless presence that continued into adulthood. It is my childish secret, so that even living in London, on the rare nights it breaks through the cloud, I get out of bed and go to a window to let it drench me in its light. But now I find I can no longer look at it, cannot stand to look at it. Fuck the moon, I think, fuck the fucking moon; and feel betrayed.

After a fitful sleep I wake before dawn. In the grey half-light the plainly furnished room with its barred window could be a prison cell and with sudden, cold precision I know that my life before this morning is no longer accessible. A barrier has come down in the night; I have been shut off from the world as it was and which now appears so far removed, a distant, light-filled place of ease and foolish innocence. Across the room Claudia and Marina are still asleep in the narrow double bed. I don’t know what our future holds, but I can’t suppress a deep sense of dread that threatens to extinguish the hope I so desperately want to maintain.

An early breakfast in the empty hotel dining room and we set off in the car, soon leaving Munich behind us. We could be aliens in a spaceship, so unrecognisable does the world look as we speed through it, so safe, tranquil, ordinary, as though nothing has happened. I’m surprised people are not staring and pointing at us as we go by, strange creatures from a another planet gazing out on their ordered world of fields and forests and sturdy Bavarian farmhouses with smoke curling from warm kitchens into the pale morning air. When the mountains rise into view their menace seems equally unreal; they are where this thing happened to Miles and I marvel at their indifference, the carefree destruction at their heart as they tower so calmly over us. When finally Innsbruck appears spread out in the valley below us it could be a surreal postcard. Picturesque Tyrolean rooftops and glinting church domes just catching the light as the sun rises over the encircling snow-covered peaks, a macabre fairy tale scene in the midst of which Miles lies, injured and alone. Silence in the car as we descend into the town, each one of us tense, braced for landing. We have no idea, we have absolutely no way of even beginning to know, what we are about to face; the future is a void.

I

We have arrived too late. Everything has happened; we are simply witnesses to the aftershock. Charlie and Ben are waiting in the hotel foyer and the two young men, fit and tanned after a week’s snowboarding, are tense, tight-faced with the knowledge of where they are about to take us. They arrived in Innsbruck yesterday evening and were waiting at the hospital for Miles when he came out of the operating theatre. Ben says the sight of him then was too difficult to be able to describe it to us; he was glad we had not yet arrived.

I hate that I don’t have those memories. I wish I could see a slow-motion replay of the accident, see his face close up afterwards, know what was going through Miles’s brain as it was splintering – I cannot bear that it was unshared. I cannot bear the isolation of that moment, the loneliness: I imagine him falling like an abandoned astronaut, no longer tethered, his lifeline floating free as he sinks through dark galaxies and whirling fragments of comprehension that the world is disappearing far behind him. I wish I could have been there, to hold him and tell him how much I loved him, how much we all love him, how we would fight for him.

Ben and Charlie take us to the hospital. As we walk into the vast glass and concrete foyer of Innsbruck University Hospital I feel the air being sucked away from me. The floor rises in waves, the walls bulge in, I can’t breathe; I have to get away. Disembodied, I look down from somewhere high above us all and watch myself talking calmly to Charlie as he leads our small group through the crowd of people towards the lift, as though this were a perfectly ordinary thing to be doing this sunny morning.

We are sitting in a row in the waiting room, waiting. The room is silent, save for the dull hiss of oxygenated bubbles coming from the glass fish tank in front of us. Inside the tank tiny iridescent fish dart and swoop, up and down, backwards and forwards, their mouths gaping senselessly. The room is small and square, three walls painted a soft sea green and the fourth, adjoining the corridor alongside it, made of thick shatterproof glass. The fish tank sits on a plain black metal table pushed up against the wall and next to it there is a small wooden shelf with water jug, glasses and a telephone for visitors to announce their arrival. There are some metal chairs, cold to the touch, and the long wooden bench on which we sit as well as a wooden coffee table with brightly coloured Austrian magazines on it. At the end of the glass wall is a door with a small silver keypad next to the handle. It cannot be opened from our side without a code; we will have to be let out of this room when the time comes. Occasionally a doctor or a nurse passes by on the other side of the glass wearing cotton trousers and overshirts the same sea green as the walls. I notice they keep their eyes straight ahead, averting their gaze from us.

Only two people at a time can visit the ward, accompanied by a nurse. I go first with Will, down the corridor that we will come to know so well, stopping at the end to take out the plastic aprons and gloves from their dispensers on the walls. Even more disoriented in this new uniform, we then turn the corner to face the ward. It feels as though we have entered an underwater world: tinted green glass divides cubicles and nurses’ stations, and everywhere is silent save for the rhythmic tidal swish of respirators and the soft sonic keening of machines, like whale calls in the deep. Nurses and doctors glide through the rooms, serious, intent on the silent bodies each beached on their high beds.

As we reach Miles’s cubicle the dread of seeing him engulfs me. Will has his arm firmly around me as we enter what is – I sense it at once – a hallowed place, a shrine; there is an overwhelming impression of a warrior, wounded, suffering. Afterwards we discover that we all felt this same thing, felt the sense of spiritual power heavy in the room and that we were on the periphery of something beyond our mortal comprehension, as though Miles were absorbed in a conversation with Life and Death and we should not presume to interrupt.

He lies on his back on a high bed in the centre of the room, perfectly still. The stillness is terrible. His strong face, the one we are so familiar with, that we know to be so expressive, humorous, animated, is closed from us in a way it would not be if he were asleep. After a week in the mountain sun his face and neck alone are tanned, a clear demarcation line where the top of his tee shirt would have been. He always tanned easily and it suited his dark looks; now that demarcation line breaks my heart. A sheet has been placed like a loincloth over his middle, but otherwise he is naked, his muscular young man’s chest and arms and beautiful virile legs defying his injury. A multitude of wires and tubes connect his brain and body to the bank of machines and electronic charts behind him which are recording every tremor of his existence, tubes coming out of his nose, his mouth, the top of his head, his chest, his wrist; but his face, bruised down the right side only, is calm, his eyes closed, the violent new scar running serenely from his hairline up and over his partially shaven head and down to the base of his right ear.

He looks so strong, so healthy, in such fine physical condition. How can it be that only his brain is damaged, and quite so damaged? It is later we are told that he comes to be known by the doctors and nurses on the ward as The Athlete; the nurses flirt coyly with the word. But it is not just his body that is powerful; something is radiating directly from him, the air is thick with his presence.

Will and I stand silently, on one side of the bed. On the other a male nurse is filling in a chart. He finishes and turns to us, apologises for intruding at this moment but explains that because Miles is on a ventilator there must be a qualified person in the room at all times. His English is impeccable. A ventilator: I wonder what the word for it is in German. In whatever language it is a thing only ever glossed over, half imagined, in a fleeting glimpse of horror. An iron lung it was called when I was a girl and polio was the scourge of the age. I remember my childish incomprehension seeing pictures of people encased in them, as though they were in an iron suitcase like a magician’s accomplice, and the shock when told they could not breathe without it.

There is too much to take in. I bend down and kiss Miles’s cheek, then the other cheek, his forehead, his nose, his neck, his chest, but it’s no good, there are too many tubes in the way. I begin to speak, hesitantly, it seems difficult. We love you so very much, Miles. You know that. We adore you, we absolutely adore you. You know, don’t you, that we are all here for you. We can feel your strong fighting spirit, you are with us as you always are. You will be all right, you’re going to be all right, you are going to come back to us. I love you so very, very much, my extraordinary, precious, beloved son.

Who cares if I am gushing. Will bends to kiss Miles too. You’re going to make it, dude, he says quietly, you’ll be back. I love you, Miles. How gentle he is, this other precious son of mine, his gentleness intrinsic to his strength.

I need to ask the nurse some questions. The tube inserted into the top of his head, so dreadful to see, is monitoring the pressure in his brain and draining away the excess fluid to reduce the swelling. The tube in his mouth is intubation into the lungs from the ventilator; the one in his nose is intubation to his stomach from a bag of liquid food hanging on a hooked stand above his head. There are more tubes, for hydration, medication, monitoring the heart, a catheter draining dark yellow urine into a bag. The machines recording Miles’s new state of limbo could be the controls of a spaceship, the flickering lines and lights on screens recording his dislocated journey into the future.

The first time I cry is in the bend of the corridor on the way back to the waiting room, out of sight of the ward. Crying in a way I don’t know about, with great racked gasps. Will’s arms are around me and I feel selfish; he must be feeling this too, it is his brother he has just seen, his closest friend and companion, but he is comforting me. We return to the waiting room and I’m conscious of composing myself to face the others, our eyes meeting first through the glass wall as they search our faces for information in a way that will become our twice daily routine over the coming weeks. Holding hands, Claudia and Marina are now led by the nurse down the corridor to see their brother.

Tuesday morning, the second day. As I walk past the nurses’ station a young doctor comes forward and asks me if I am Miles’s mother. He hands me a copy of a letter received by fax that morning and tells me that the doctors and nurses have been reading it.

For the attention of the Family of Miles Kemp

We are thinking of Miles at this very tough time and wishing him the very speediest of recoveries.

Miles has been playing a critical role in one of the BBC’s most important projects. Throughout he has shown an intelligence, professionalism, commitment and charm.

Please let me know if there is anything we can do for Miles or yourselves at this time.

John Smith

Chief Executive, BBC Worldwide

I can’t control my tears. The letter gives Miles substance, a background, the importance of which we are only beginning to learn. In each new institution he will be admitted to in the months to come he will simply be another TBI, another Traumatic Brain Injury. He’ll have no history, no personality; all that defines him will be his sex, his age and his injury. The medical staff cannot know that he is thoughtful, funny, brave, kind, impatient and irascible. They can have no idea about his lived life, its failures and achievements, the way his energy and presence seem to contain some electrical force. The only story they will have in the notes that accompany him is that he once snowboarded, not that he likes boxing and playing poker, writing poetry and playing the fool.

Turning into Miles’s room now the shock of seeing him wired up and motionless on the bed makes a mockery of the letter in my hand. It was only ten days ago in the cosy sitting room at home with the fire lit and a glass of our favourite Rioja that we had a long discussion about his work and his plans for the future. After putting his fledgling company, K Tech, on ice two years ago he joined an international firm of management consultants and it was from there that he presented and won the account for them with the BBC. He had begun working at the BBC only a few months ago; he would be proud of this letter. Pulling up a chair next to his bed I read it aloud to him, and then I read it again, hopelessly searching his face for a reaction. Of course there is nothing, the softly flashing lights and the undulating lines on the screens above his bed the only proof that he is alive. He is there but not there, though a little part of me is certain he is listening and hearing me. I must hold on to this, my hope is tethered to it, a fragile skein of hope.

At the end of the morning visit we have our first appointment to meet Miles’s doctors. We are back in the waiting room, waiting in silence, for fear that if we speak our dread will spill out. The fish continue to swim in their tank, the overhead strip light glares relentlessly. This room feels like an antechamber to horror, the air heavy with the distilled fear of all the people who have waited here before us.

I need to clear my mind for this meeting, but it’s a scrambled mess of unfinished thoughts that keep sliding away, of questions I can’t frame. With grim relief I see through the glass wall two men in green surgical uniforms walking towards us. Neither is what I expected of a neurosurgeon, the older man with his ruddy jovial face and thick blond moustache, the younger man tall, tanned and athletic-looking, both more like men with outdoor pursuits than doctors. I suppose this is the Alps, I think, but Miles’s life is in their hands; I need to believe in them. When the older man introduces himself his voice is calm, authoritative, his expression no longer jovial as he looks around at each of us, one by one, taking us in. I am Dr Stizer, he says. I operated on Miles on Sunday evening. He had suffered a severe brain injury and was unconscious on arrival here. We removed a large piece of bone from his skull to relieve the pressure on his brain. He is now in an induced coma and breathing by means of a ventilator. We do not know at this stage what the outcome will be. He lifts his eyes to the ceiling and raises his arms, hands upturned, a gesture of supplication. It is in God’s hands, that gesture seems to say, and I think I don’t want it to be in God’s hands, look what’s already happened in God’s hands. He looks searchingly around at us once more and his expression is so concerned, so kind, that I can see he cares about the young man who is his new patient and he cares, too, about us. I understand the shock you are feeling, he says quietly. We will do our best for Miles. But now, please ask me any questions you may have.

Dr Stizer is a good man. But what questions? All that matters is, will Miles live? He cannot answer that.

Leaving the hospital together we walk in silence, each isolated in our need to comprehend what has happened. Below us the river Inn flows busily, people stroll past or sit at pavement cafés chatting in the sunshine, the mountains continue to sparkle under a cloudless Alpine sky. The serenity is monstrous. Claudia starts to walk fiercely ahead of us, then stops and turns to me, her face wet with tears: I’m going to take the cable car up the mountain, I need to be on my own. I’ll be back. She turns off to cross a bridge and disappears from sight. I look at Marina and her eyes are wide with pain as she says she will take a walk along the riverbank, giving me a quick kiss goodbye as she descends the steps leading down to the water’s edge.

We all need to be on our own. The information just delivered to us by the two surgeons has become a broken jigsaw of meaning, splintered pieces that need to be reassembled somewhere, alone, in peace. Three of us are left behind standing on the edge of a bridge that leads into the cobbled streets of Innsbruck Old Town and I can see sunshine warming the ancient stone buildings. It looks peaceful; I want to go there. I turn to Will and he understands. He and his father will go back to the hotel and get some lunch.