Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

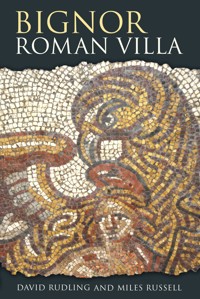

Discovered in 1811, Bignor is one of the richest and most impressive villas in Britain, its mosaics ranking among the finest in north-western Europe. Opened to the public for the first time in 1814, the site also represents one of Britain's earliest tourist attractions, remaining in the hands of the same family, the Tuppers, to this day. This book sets out to explain the villa, who built it, when, how it would have been used and what it meant within the context of the Roman province of Britannia. It also sets out to interpret the remains, as they appear today, explaining in detail the meaning of the fine mosaic pavements and describing how the villa was first found and explored and the conservation problems facing the site in the twenty-first century. Now, after 200 years, the remarkable story of Bignor Roman Villa is told in full in this beautifully illustrated book.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 278

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To Sheppard Frere (1916–2015)

Romanist, Scholar, Academic, Historian and Archaeologist par excellence

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to: Mark Hassall and Richard Reece, inspirational tutors on so many aspects of Roman archaeology at the Institute of Archaeology, University College London; Ernest Black, not only for many discussions concerning Bignor Villa over the years (especially concerning its phasing and the possible impact of historic events such as plague and civil insurrection) but also for his extensive help with this book (particularly his significant contribution to chapter 6); and to the Tupper family for their continued commitment to the care, interpretation and preservation of Bignor Villa. Without them all, Romano-British archaeology would be much the poorer.

Thank you to all the staff, students and volunteers who helped with the UCL excavations between 1985 and 2000. In particular, thanks are due to Luke Barber who supervised the 1990–2000 excavations.

Special thanks must go to: Lisa Tupper, for her considerable and enthusiastic help at all stages in the preparation of this particular work; Justin Russell, for producing the excellent site plans at (very) short notice; and all at The History Press, especially Cate Ludlow and Emily Locke, for their belief that, however many deadlines were missed, this book would eventually see the light of day. Thank you also to Mary, Benjamin, Bronwen, Megan and Macsen for cheerfully coping with the impact of Romano-British archaeology for so long.

This book is respectfully dedicated to Sheppard Frere whose book Britannia: A History of Roman Britain, first published in 1967, shaped so many minds and whose excavations at Bignor between 1956 and 1962 so completely changed our understanding of the villa.

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Introduction

I

Discovery and Excavation

II

A Tour of the Mosaics

III

Phasing and Development

IV

Finds and Dating Evidence

V

Experiencing the Villa

VI

Ownership

VII

Everyday Life

VIII

The Rural Context

IX

Bignor and Sussex Villas

X

How Did it All End?

XI

Unanswered Questions

Visiting Bignor

Glossary

Image Sources

Further Reading

Plates

About the Author

Copyright

INTRODUCTION

The physical manifestation of Roman cultural life, or Romanitas, in the countryside, and indeed the most well-known and popular aspect of Roman Britain today, is the villa. Some archaeologists and historians have noted their dislike of the term ‘villa’ due to its connotations of ‘luxury holiday’ or ‘retirement home’ combined with its apparent inappropriateness when comparing British sites with those grand Roman-period villas found across Italy and the Mediterranean. The trouble is, that’s just what most Roman villas appear to represent. A villa, in the context of Roman Britain, was a place where the nouveau riche spent their hard-earned (or otherwise acquired) cash. It is true that the majority of villas in Britain were at the centre of working, successful agricultural estates – profits generated from the selling of farm surpluses and local industrial enterprises such as stone quarrying, pottery manufacture and forestry, presumably providing the necessary financial resources for home improvement, but lots of villas are as far away from ‘normal’ working farms as one could expect.

Many villas, whether in Britain or elsewhere in the Roman Empire, possessed elaborate bathing suites, ornate dining rooms and generally had a high level of internal decor. In contrast, working farms possessed more basic, functional domestic accommodation with easy access to pigsties, cow sheds, grain stores and ploughed fields. In this respect, the earliest Roman-period villas of lowland Britain can perhaps be better compared with the grand estates, country houses and stately homes of the more recent landed gentry of England, Scotland and Wales. These houses represented monumental statements of power designed to dominate the land and impress all who passed by or who entered in. As the home of a successful landowner wishing to attain a certain level of social standing and recognition, the seventeenth-century stately home or country house was the grand, architectural centrepiece of a large agricultural estate where the owner could enhance his or her art collection, entertain guests of equal or higher standing, develop business opportunities, dispense the law and dabble in politics. In this respect the larger Romano-British villas were probably little different.

Villas are useful components in the archaeological record of Roman Britain, for they act as indicators of the relative success of the adoption of Roman culture in the province, especially in the countryside. These were not structures created by the state for ease of administration (towns), nor subjugation (forts); they were not forced upon the native population, rather they were developed by those who were, or who wanted to be, culturally ‘Roman’. They were all about show and social standing. Given that the population of Britain at this time was predominantly rural, the distribution of villas across the British Isles should provide an idea of the relative ‘take-up’ of Roman fashions from the late first century AD to the collapse of central government authority in the early fifth century. Similarly, places where villas are absent might, in theory at least, be reflective of areas where the population did not desire, acquire nor even aspire to so many of the cultural attributes of Rome.

The villa of Bignor in West Sussex, southern England, is justly famous for being one of the best-preserved rural Roman-period buildings in the country. Discovered during ploughing in 1811, the villa complex was extensively explored and, for the time, well recorded with meticulous plans, isometric drawings and some artefact illustrations. Unfortunately, as was usual with early antiquarian fieldwork, these investigations were generally lacking with regard to both stratigraphic observations and the retention of all but the most interesting of finds. During this time, a series of reports on the excavations were published together with a set of detailed engravings. Although far less objective than the archaeological plans, elevations and technical drawings compiled by archaeologists today, these hand-coloured images are highly evocative, providing a wealth of information concerning the state of the villa at the time of first investigation.

Protective buildings were erected over the mosaics by George Tupper, who farmed part of the site, and by 1815 it had become a popular tourist attraction. Fortunately the Tupper Family, who now own all of the site, have never lost interest in Bignor and today it is one of the largest villas in Britain that can be visited by the public. To enter the independently thatched cover buildings and gaze down at the mosaics is an undeniably uplifting experience. The site is, of course, important, not just because of the visitor experience that it represents, but because this is one of the best understood of all Romano-British rural ‘power houses’. Whilst much of the site was exposed during the early nineteenth-century excavations, large areas were thereafter backfilled and returned to arable cultivation, and thus also exposed to further plough damage. Subsequent research at Bignor has included several episodes of re-excavation, limited investigation of new areas, geophysical survey and fieldwalking as well as an extensive re-analysis of previous discoveries.

The book before you now is an attempt to explain one of the best-preserved and certainly more famous of Romano-British villas in Britain; described by its first explorer as ‘the finest Roman house in England’. We will, therefore, take you on a journey, from the moment of first discovery on that fateful morning in July 1811, through the subsequent history of site exploration and excavation. We will then examine the remains preserved on site today and explain how our understanding of site phasing and developmental evolution has changed over the years. An opportunity will also be made to put the villa in context: who lived in it, how was it used and what did it all mean in the context of Roman Britain, before attempting to explain how in its final form this luxury residence with strong classical overtones, nestling below the grass-covered South Downs, came to an end.

I

DISCOVERYAND EXCAVATION

In 1811, George, Prince of Wales, became Regent of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, due to the incapacity (and perceived insanity) of his father, King George III. Georgian Britain was, at this time, heavily involved in a number of European wars, most notably against the armies of Napoleonic France. At home, in England, the first major Luddite uprisings against the labour-saving machines of the Industrial Revolution, were beginning in Northamptonshire whilst, across Scotland, the infamous Highland clearances resulted in the expulsion of crofting tenant families and the mass emigration of thousands. The year 1811 also saw Jane Austen publish her first novel, Sense and Sensibility, whilst on the beaches of Lyme Regis, in Dorset, Mary Anning discovered the first complete fossilised skeleton of an Ichthyosaur and in Sussex, farmer George Tupper found what was to prove to be one of the finest Roman-period villas in the country.

DISCOVERY

It was the morning of Thursday, 18 July when George Tupper hit what appeared to be a large stone whilst ploughing in ‘Berry (or Bury) Field’, near the village of Bignor in Sussex. Bringing the horse plough-team to heel, Tupper investigated the nature of the obstruction, quickly discovering that the plough-struck stone was in fact part of a larger structure, what we now know to be the edge of a piscina or water basin in room 5 of the villa. Grubbing around on his hands and knees, Tupper soon found himself staring down in amazement at the tessellated face of a young man. Subsequent energetic spoil clearance revealed the larger mosaic depicting the figure of the man, naked except for a bright red cap and fur-trimmed boots, an immense eagle and, further afield, a series of scantily clad dancing girls.

In fact the pavement comprised six dancing girls or maenads (of which five wholly or partly survive today) surrounding the stone-lined basin and, in a recessed ‘high’ end on its northern side, a circular mosaic depicting Jupiter in the guise of an eagle caught in the act of abducting the shepherd boy, Ganymede. Subsequently, to the west of this, Tupper also found parts of a second pavement, again with two compartments, this time comprising the Four Seasons, represented by a well-preserved head of Winter, and portions of mosaic containing dolphins and a triangle enclosing the letters TER. To say that he was awestruck would have been an understatement. In one short period of soil clearance, Tupper had revealed, for the first time in nearly 1,500 years, an amazing collection of high-quality Roman floors.

Close up of mosaic depicting the face of a young man, now known to be a portrait of the Trojan prince Ganymede, the first of the decorated floors pieces of Bignor Villa to be exposed by George Tupper in 1811.

Ganymede and Jupiter, in the guise of an eagle, from the mosaic of room 5 as recorded by Samuel Lysons and Richard Smirke in 1817.

The discovery of the decorated pavements was quickly communicated to John Hawkins, George Tupper’s landlord; an influential local resident, who lived nearby in Bignor Park. Hawkins, a man of considerable wealth built upon his family’s investment in Cornish mining, had purchased Bignor Park House five years earlier, in 1806. Trained as a lawyer, Hawkins had travelled extensively in the eastern Mediterranean, where he had acquired an impressive collection of ancient artefacts. A Fellow of the Royal Society, he was also an enthusiastic student of both science and the arts and he responded with great enthusiasm to the news that a major Roman villa had been discovered on his land.

As a gentleman with knowledge and experience of antiquities, Hawkins took over responsibility for further excavation of the Roman remains at Bignor, inviting Samuel Lysons, by trade a London lawyer but also vice president of the Society of Antiquaries of London and a Fellow of the Royal Society, to supervise and record the excavation work. Unfortunately, Lysons’ extensive professional and antiquarian duties, combined with rheumatism and other illnesses, meant that he could spend only a limited amount of time at Bignor, a situation which resulted in regular correspondence between himself and Hawkins until the death of Lysons in June 1819. The final season of villa examination in 1819 involved correspondence between Hawkins and Samuel Lysons’ brother Daniel, Rector of Rodmarton, Gloucestershire, who took over his late brother’s role in respect of clearance work. Fortunately the correspondence covering both the investigation and subsequent display of the villa have survived, allowing a unique insight into this early nineteenth-century archaeological ‘direction by letter’.

The face of Winter as recorded from a mosaic in room 26 in an engraving by Samuel Lysons and Richard Smirke.

A rather fierce-looking dolphin from a panel of mosaics (now lost) in room 26 in an engraving by Samuel Lysons and Richard Smirke.

John Hawkins of Bignor Park.

Samuel Lysons.

EXCAVATION STRATEGY

The main aim of Samuel Lysons’ initial work was ‘laying open the foundations of the walls’ in order to ‘trace the plan of the building’. Such a practice of wall chasing was fairly common for the period, trenches being cut by labourers across a buried site until masonry was located, then changing direction in order to follow the line of the walls and complete the outline of individual rooms. The dangers in adopting such an approach were, of course, a general lack of contextual understanding, dateable artefacts being removed from the layers in which they had been deposited without full understanding of their meaning or significance.

It is the responsibility of the modern archaeologist to record everything recovered from an excavation in an equal amount of objective detail. On an ideal site, everything is carefully dug by hand, all defined features, such as pits and postholes, being half sectioned so as to observe and record the backfill, whilst ditches and other large linear cuts are sampled or emptied at fixed intervals so as to establish the complete nature of the depositional sequence. Today all layers, fills, cuts and structures are allocated unique and individual ‘context’ numbers and everything is recorded in equal detail on pre-printed sheets. Plans and sections are drawn; photographs, spot heights and environmental samples taken. Sadly, it has not always been like this.

Most antiquarian and early archaeological excavations were largely motivated by the desire to examine structures and accumulate collections of artefacts, mostly metalwork and pots. Earthworks were often thought of as little more than the surface indicators of buried treasure, with the result that many prehistoric barrow mounds and Roman-period structural remains were identified, dug into and destroyed. A ditty composed by Martin Tupper (no relation to the Bignor Tuppers) during the exploration of a Romano-Celtic temple at Farley Heath in Surrey, around 1848, typifies the approach of many of these earliest of investigators:

Many a day have I whiled away

Upon hopeful Farley Heath

In its antique soil

Digging for spoil

Of possible treasure beneath

The bathhouse of the southern wing under excavation, from an engraving accompanying Lysons’ 1815 account published in the Reliquiae Britannico-Romanae.

Ironically, then, at exactly the same time that Europeans were becoming aware of the ancient past, especially in the writings, teachings, art and general philosophy of their Egyptian, Persian, Greek and Roman forebears, a large number of archaeological sites were being irrevocably damaged.

For the majority of those engaged in antiquarian pursuits, the ends justified the means, and the end in most cases was represented by the artefact. Context was, in this case, largely irrelevant, as long as some new piece of the past could be located and curated. Excavations were, in some instances, designed purely to find things as quickly and efficiently as possible. A visit to any regional museum in Britain will often demonstrate the relative success of these early diggers, funerary pots, coins, bronze axes, stone tools, brooches and the like being the ultimate prize. Unfortunately data surrounding such artefacts, where and when they were found, was often only recorded, if it were recorded at all, in the memories and random notebook jottings of those engaged in the excavation.

Samuel Lysons was different from most of his contemporaries; part of a small group of antiquarian researchers considered today to represent the founding fathers of British archaeology. Although the revelation that an understanding of specific layers of soil, rather than just the location of walls and the quantity of artefacts, could clarify the sequence and chronology of ancient sites was arguably not fully appreciated until the final decades of the nineteenth century, Lysons believed that the key to any archaeological examination was the accurate recording of masonry walls, floors and buildings (but generally not cut features such as pits, postholes and ditches – which were then probably not recognised nor fully understood) through plans and elevations and the swift dissemination of the results. Accordingly, together with Hawkins and Tupper, the excavation of the villa at Bignor was undertaken with due seriousness, great attention being paid to the methodical recording of remains, trenches being cut in order to expose layers and walls and examine the relationship between structural features.

Close up of a coloured engraving by Richard Smirke from the Reliquiae Britannico-Romanae showing the Venus mosaic of room 3 under excavation. The gentleman contemplating the floor is undoubtedly John Hawkins.

Much of the basic day-to-day movement of soil was undertaken by farm labourers, organised through the efforts of George Tupper, Hawkins and Lysons not being on site at all times to oversee the clearance, supervising at a distance and sometimes, in the case of Lysons, directing excavation strategy by letter. This form of ‘remote direction’ had the disadvantage that strategy could not always be closely overseen or implemented (see colour plate 1), whilst changes to soil removal could not be subtly modified or altered. Also, finds recovery could not be adequately monitored and it is likely that large amounts of artefacts and other types of evidence such as animal bones were lost during the initial phases of clearance.

Keen to record the remains in situ, exactly as they were revealed, Samuel Lysons did not attempt any reconstruction or aesthetic ‘beautification’ of the buildings exposed, as was frequently common amongst his peers, taking care to record all and every imperfection and area of disturbance. Much of the correspondence that survives between himself and Hawkins, the man on the scene, relates to the importance of accuracy in measurement, the systematic approach to building exposure and the recording of architectural detail. Special finds, such as coins and other metalwork, where spotted during soil clearance, were examined and noted, whilst each defined room or major feature was described in detail and separately numbered on Lysons’ ‘Great Plan’ (page 16).

Lysons was aided in his recording work by two draughtsmen who are well known and respected for their recording of remains of antiquarian interest, initially Richard Smirke and later Charles Stothard. Lysons and his colleagues published the results of their labours at Bignor and at other Roman-period sites across England in a number of beautiful, self-financed tomes of illustrations (but not text), including the multi-volumed Reliquiae Britannico-Romanae: Containing Figures of Roman Antiquities Discovered in Various Parts of England. In addition, with regard to the excavations at Bignor, Lysons also read three papers at meetings of the Society of Antiquaries of London, and these were subsequently published in the Society’s proceedings. For considerably wider readership, and with the encouragement of both Hawkins and Tupper, Lysons set about compiling a site guidebook, one of the first of its kind for an archaeological site in Britain.

Lysons’ ‘Great Plan’, with most of the rooms numbered, compiled during the nineteenth-century excavation and redrawn in the twentieth century by Robert Gurd. Note that Bignor is depicted as a single-phase construction.

Site security, as well as its long-term preservation and conservation, were key concerns for Tupper, Hawkins and Lysons. Money was a major problem throughout the project and a number of the surviving letters between Hawkins and Lysons outlined the need to secure sufficient finances to complete the work and ensure the full exposure of the villa. In the days before developer or state-sponsored finance, money could only be secured via private donations or the sale of souvenirs. Sales of guidebooks, reports and engravings produced some much-needed cash, as did the ever-increasing number of tourists to the site, although Hawkins fumed that one important visitor, George, the Prince Regent, provided ‘only two one pound notes’, a sum Hawkins treated with derision.

THE 1812 SEASON

After the original exposure of the Ganymede floor, the mosaic was reburied until June 1812. By this time George Tupper had become concerned about weathering and deliberate vandalism, determining to protect the floor ‘from intruders by a high thorn fence and from nightly depredations by the erection of a hovel’ in which one of his sons could sleep. Tupper was particularly concerned about ‘the raising of tesserae’ within the Ganymede and Dancers mosaic, caused by earthworms – Hawkins noted in a letter that ‘this evil would be removed by keeping the place dry’. By the summer of 1812 work was underway to erect a cover building over the exposed mosaic in order to protect it from the degradations of the British weather. Today this structure, together with the other flint-walled, thatched ‘hovels’, are amongst the earliest, if not the earliest, archaeological cover buildings in Britain and north-western Europe.

The structures designed to protect and preserve Bignor villa were mostly, although not exclusively, built directly on to the Roman walls, using much Roman building materials found close to hand. Such materials included flints and greensand stone found on the site during the exposure of the pavements as well as that uncovered during ground probing beyond the main area of interest. According to Hawkins, however, Lysons was concerned that no part of the villa ground plan should be ‘defaced in search of stones’ for such rebuilding. The roofs of the cover buildings were made of thatch, a distinctive and attractive material which is still in use today at Bignor, helping to give the site its special charm.

The most important new discovery in 1812 was part of ‘a very beautiful pavement extending Eastward and Northward (under the Orchard Hedge) … It is full three feet under the surface of the ground.’ This mosaic, in what is now labelled the ‘Venus’ room (3), was, when fully exposed, found to contain an exquisitely formed female portrait (‘Venus’) surrounded by a nimbus in a circle and flanked on each side within the apsidal northern end of the room by a peacock or long-tailed pheasant, cornucopiae and foliage. To the immediate south, a rectangular panel containing scenes from a gladiatorial duel between winged cupids was revealed, together with a large square area enclosing an octagon composed of eight rectangular compartments, each containing a dancing cupid. Substantial areas of mosaic were missing due to the collapse of the underlying (under-floor) hypocaust heating system, probably caused by the impact on the suspended floor of the original heavy Horsham Stone roof, which collapsed following the final abandonment of the villa.

Another discovery at this time was the small rectangular room (6), which occupies the space between the northern projection of the Ganymede mosaic room (7) and that which functioned as an anteroom (5) to the south of the chamber (3) containing the ‘Venus’ and Gladiators mosaics. This room has a geometric mosaic floor consisting of two square areas separated by a narrow rectangular one. Beneath this floor are the remains of another hypocaust heating system with a stoke-hole and furnace area on the north side of the north wall. Lysons was of the opinion (wrongly as it now seems) that this furnace and hypocaust were also the source of the heat for the adjacent ‘great room’ (i.e. that with the Ganymede and Dancers mosaics) and there is no evidence for heating beneath this room, which is today regarded as an unheated ‘summer’ dining room. There was also no communication between the two rooms, which are separated by a wall and have floors at different levels. It is possible that this small but high-status room (given the mosaic floor and underfloor heating) may have been a bedroom or office, entered from the west, with a bed or table at its eastern end. Such a room may have been used by the owner of the final courtyard villa.

The early nineteenth-century flint-walled, thatched cover building erected over room 3 in order to protect the Venus and Gladiators mosaic.

The portrait of Venus in room 3 from an engraving by Lysons and Smirke.

Hawkins wrote to Lysons informing him that in 1812 the ‘whole of the western pavement’ was uncovered, referring to the so-called Four Seasons mosaic, in room 26. It too was provided with an ‘open shed or hovel’ as a cover building. A request by Hawkins for Lysons to bring some varnish, hints at the rather rudimentary conservation and display techniques of the early nineteenth century. During 1812, visitors to the site exceeded 500 ‘of the superior classes’ as recorded in the visitors’ book. Such visitors were able to purchase from Tupper for twopence a hand-coloured Lysons’ print of either the Ganymede or Head of Winter mosaics. Thus began one of the earliest archaeological tourist sites in England and today we are able to visit and enjoy the Bignor mosaics and villa buildings because of the site’s long success as a tourist attraction rather than a full return to cultivation and the ultimate destruction of the archaeological remains by ploughing and tree planting.

Other excavations across the site in 1812 included those exploring the south side of the Ganymede room, which found the remains of an east–west corridor or portico (10) containing a geometric mosaic. Re-exposure of, and erection of a cover building for, the western part of the mosaic was not undertaken until 1976.

THE 1813 SEASON

The excavation campaign of 1813 concentrated upon the southern end of the ‘Venus’ room, revealing a range of rooms built at the western side of the main court. One of these rooms (27) appeared to have contained a fireplace or hearth at its eastern wall. Another such fireplace was also located in a room (29) to the south. Elsewhere, in the north range, on either side of room 7, were rooms 9, 12–15, 16 and 24, which lacked mosaic pavements or decorated floors.

A cover building was erected over the ‘Venus’ floor, directly on to the surviving Roman walls, and this, when combined with the varied and inventive advertising measures undertaken by Hawkins, helped to attract record numbers of visitors to the site, most apparently confessing that ‘it exceeded their expectations’. One of these early visitors was, as already noted, the Prince Regent, who made a disappointingly small (£2) entrance payment to Tupper. Hawkins reveals that he had hoped that the Prince would more readily assist ‘towards a permanent conservation and exhibition of our Roman Villa’, but this was not to be, ostensibly because of queries that if the site were bought, becoming ‘public property’ whether the ‘remains would be better preserved?’ ‘I much doubt if they would,’ Hawkins was later to say, ‘for what interest is there so strong as that of a proprietor?’

THE 1814–17 SEASONS

By late 1814, excavations at Bignor had expanded to include the north-east and south-east corners of the courtyard, the fine centrepiece to the Medusa mosaic (room 56) being discovered on land to the east of Tupper’s main holding, in a field known as ‘Town Field’. Owing to the fact that this was common land, Tupper did not immediately set about erecting a cover building over the find in order to protect the Medusa mosaic, for this would have required the permission of both the lord of the manor and other copyholders. Finally a brick-built shed was erected in 1818 and the mosaic saved.

The Medusa pavement was revealed to have been the floor of a changing room (or apodyterium) for a large and elaborate suite of baths flanking the eastern margins of the southern side of the south corridor (room 45). The main excavation of the baths took place in 1815 and immediately to the west of the changing room was a cold room or frigidarium with a large plunge pool (room 55). The northern part of this room was paved with an unusual chequer pattern of tiles, the lighter ones being of a hard white stone, whilst the darker ones were of Kimmeridge shale from Dorset. To the west were various heated rooms, including a warm room or tepidarium (53), a hot room or caldarium (52) with a hot bath (alveus), and perhaps also a hot dry room or laconicum (54b). Unfortunately only fragmentary traces were found of the original mosaic flooring in the heated areas of the baths, one fragment depicting ‘an ivy leaf and other remains of ornaments’ but indicating ‘that the pavement had been in the same style as those discovered in other parts of the building’.

The portrait of Medusa in room 56 from an engraving by Lysons and Smirke.

The plunge pool of the frigidarium in the south wing, 1993. Scales: 2m and 1m.

In 1815, Robert Carr, the rector, gave his permission for the excavations to extend to the west of Tupper’s field on glebe land. The resulting excavations in 1815–16 revealed an ‘unfinished’ bath suite (rooms 36–39) along the western side of the west range of the villa. Other excavations in 1815 investigated the small courtyard in the north-west corner of the villa (1 and 2). Hawkins noted the discovery in this area of columns of at least two sizes and it is reasonable to assume that the outer wall of the portico may at some time have been open externally with small columns supported on walls.

Another achievement in 1815 was the publication by Lysons of a small guidebook, something that had been eagerly awaited by both Hawkins and Tupper for some considerable time. By now the number of visitors to the site had increased significantly and, during the 1815 season of excavations, the visitors’ book had 940 entries, the number probably accounting for well over 1,000 visitors assuming that not all those forming a group will have signed separately.

During 1816 and 1817 the excavations continued to trace the foundations of the walls on the east and west sides of the ‘great court’ and it was established that the corridor ‘extended all round the court’. At the northern end of the western part of the portico the excavations revealed a room (33) with a square mosaic floor comprising a head of Medusa at its centre and the heads of the four seasons in its spandrels. The quality of the mosaic floor in this room was far inferior (‘rudely executed’) to all the others mentioned above and Lysons was of the opinion that it was made ‘at a late period’, although today this mosaic is considered to be the earliest in situ mosaic at Bignor. Originally it provided the floor of the northern wing room of the winged-corridor villa. Subsequently, during the courtyard phase of the villa, this room acted as a link between the northern and western corridors, the major difference in ground level being solved by means of two steps. Excavations to the east also established the east portico (rooms 60, 61), which completed the enclosure of the ‘Great Court’.

The bathhouse of the south wing during excavation, showing the cold plunge and adjoining heated rooms, looking south towards the Downs.

A sketch of the small courtyard (rooms 1 and 2) in the north-western corner of the villa, drawn by John Hawkins in a letter to Samuel Lysons dated 27 May 1815.

A surprising discovery in the south-east corner of the Great Court were various wall foundations (room 59), at right angles to each other, but on a completely different alignment from those of the Great Court, further traces being found in the southern corridor and the adjacent baths. Lysons thought that these walls seemed ‘to be part of a former building’ predating the main phase.

Further east, other discoveries in Town Field included the foundations of several buildings (rooms 66–68; 69; 70–74), all set within a boundary wall that had not been constructed at right angles to the eastern side of the Great Court. Although not mentioned by Lysons, his final (1819) plan of the site shows the positions of three entrances into the outer courtyard, two from the east (75 and 76) and one from the south (77). Other excavations in late 1817 explored the south-western part of the courtyard complex to the south of the main western range (rooms 42–44). Hawkins noted that this area contained a ‘vast accumulation of rubbish’, including ‘the best preserved capital of a column that I have yet seen’. Problems with differing floor levels at this location were again found to have been solved by the use of stairs (44).

After the death of Samuel Lysons on 29 June 1819 it was left to his brother Daniel to complete the Reliquiae Britannico-Romanae (‘the Great Work’) and to produce a new impression of the Bignor Guide (1820). The price of the Bignor part of Reliquiae Britannico-Romanae was twelve guineas (£12 and 60 new pence) and the Bignor Guide was three shillings (15 new pence), both substantial sums in the early nineteenth century. It is clear from a letter sent to Daniel by Hawkins, who was finishing the excavations in the south-western corner of the Great Court, that Hawkins was aware of ‘some mistake in the measurement of the great plan, the Southern wall having been laid down too far to the North, nor is it possible to correct this mistake without re-engraving the whole plate, which the importance of correction will not justify’.

Cover to the first guidebook to Bignor Villa published in 1815.

A sketch plan of walls uncovered to the east of the main house, drawn by John Hawkins in a letter to Samuel Lysons dated 11 October 1817.