13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

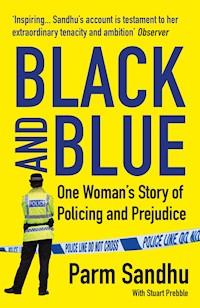

'Inspiring... Important' Observer 'A page-turner which everyone who cares about policing and justice in Britain should read.' Meera Syal At the point of her retirement from the Metropolitan Police Service in 2019, Parm Sandhu was the most senior BAME woman in the capital's police force. She was also the only non-white female to have been promoted through the ranks from constable to chief superintendent in the Met's entire history. In this enthralling memoir, Parm chronicles her journey from life on the outskirts of Birmingham as the fourth child of immigrants from the Punjab to the upper echelons of the Met. Forced into an abusive arranged marriage aged just 16, Parm made the decision to escape to London with her newborn son and later joined the police as a constable. During her thirty-year career, Parm worked in everything from crime prevention to counter-terrorism, and she also served in the Met's police corruption unit. She played a senior organizing role in the London Olympics and was the superintendent on duty when Lee Rigby was beheaded in the street in Greenwich. However, Parm's time on the force was chequered throughout with incidents of racial and gender discrimination, and, after deciding to make a stand, she found herself facing a spurious charge of gross misconduct. Black and Blue tells her shocking story and of her quest for justice in her police work and for herself. It is a story that cannot fail to inspire anyone who has experienced prejudice or abuse of any kind.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

BLACK AND BLUE

Parm Sandhu joined the police force in 1989 and rose through the ranks to become the highest ranking female Asian officer in the Met. Among many honours, Parm has been awarded Asian Woman of the Year, the Vasakhi Award (Mayor of London) and the Sikh Women of Distinction Award (Sikh Women’s Alliance).

Stuart Prebble was for many years a leading television journalist, notably on ITV’s World in Action programme, and later became CEO of ITV. He is now a successful producer and writer.

‘Inspiring... Sandhu’s account of her ascent through the ranks of the Met is testament to her extraordinary tenacity and ambition... Shines an important light on the Met’s failure to understand and represent the diverse community it serves.’ Observer

‘Parm Sandhu’s story is an inspiration to anyone who has found themselves struggling against adversity. It’s also a page-turner which everyone who cares about policing and justice in Britain should read.’ Meera Syal

‘A captivating exhibition of courage and conviction, Sandhu’s story is an inspiration for those facing prejudice and a revelation for those in the dark.’ David Lammy MP

‘A brilliant book full of nail-biting tension and shocking statistics that make it hard to put down. It made me simultaneously angry and tearful. Parm’s story leaps off the page and makes you want to walk every step of the way with her, to be her friend, to stand shoulder to shoulder with her.’ Andi Oliv

‘Black and Blue is a profoundly moving account of life as a senior police officer. It is essential reading for anyone who wants to understand our police service.’ Rob Rinder

‘A powerful, page-turning – and often shocking – story of courage. It’s essential reading for those interested in the state of policing Britain, and for readers who enjoy memoirs with inspirational bite.’ Joanne Owen, LoveReading

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by Atlantic Books,an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Stuart Prebble and Parm Sandhu, 2021

The moral right of Stuart Prebble and Parm Sandhu to beidentified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them inaccordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or byany means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, orotherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright ownerand the above publisher of this book.

The picture credits on p.323 constitute an extension of thiscopyright page.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders.The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectifyany mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available fromthe British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-83895-264-8E-book ISBN: 978-1-83895-266-2

Design and typesetting benstudios.co.ukPrinted in Great Britain

Atlantic BooksAn Imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Toby

Authors’ note

Victims of crime and abuse are entitled to privacy and so, in some cases, are the perpetrators. For this reason we have made some minor amendments of detail, in order to protect identities where necessary.

Contents

Prologue

1A Difficult Child

2Hostage

3Escape

4‘Managing my shame’

5‘You’ve not had your bum stamped!’

6‘A spade in uniform’

7Zulu

8‘Prisoners, prostitutes and plonks’

9‘Never apply again’

10‘Shi-ites and shitties’

11A Death a Day

12‘Police officer or single parent’

13The Diversity Directorate

14Making History

15‘It’s you!’

16Croydon

17The Cannabis Farm

18The Pope and I

19The London Olympics

20Own Goals

21‘Help for Heroes’

22‘He went berserk!’

23‘Belittle, intimidate and bully’

24‘Your Indian heritage’

25Gross Misconduct

26‘You have personally failed!’

27‘Don’t let the bastards grind you down’

Afterword to the Paperback Edition

Acknowledgements

Illustration credits

Prologue

These days, the Eleanor Street district of Bow in the East End of London isn’t somewhere you’d want to visit at night. Small industrial units line up on one side, and a railway bridge at the junction with Tidworth Road provides shelter for all manner of nefarious activities. And it certainly wasn’t somewhere you wanted to spend time in the dark winter months of the 1990s. All sorts of street crime, drug abuse, prostitution and burglaries were rife in the area, and little in the way of street lights made it feel like a dangerous place to be.

One freezing cold night in February 1990, at a point just below the railway bridge, the designated Metropolitan Police Area Driver for the borough pulled his car over to the side of the road. Area Cars ferry firearms officers or local patrol officers, and are kept on standby in major cities and large urban counties for moments when emergency help is needed. The cars are always high performance, and the men who drive them are high-performance officers – specially trained in tactical pursuit, advanced driving and stopping fleeing offenders – their status frequently the envy of fellow officers.

On that February evening, however, this particular Area Driver wasn’t feeling very revered. Rather the reverse, because – before leaving the police station at the start of his shift – he’d had an altercation with his superior officer. The argument was over the question of who would accompany him on his patrol that night. His usual partner was not available, and so his inspector asked him to take a new recruit along with him instead.

Area Drivers are so exalted they’re usually allowed to choose their own partner, and this one informed his superior officer that he didn’t want to babysit some rookie. However, when the exact identity of his new partner was revealed, his objections multiplied. If it wasn’t bad enough that the officer in question was fresh out of Hendon, she was also female, she was young, and she was Asian.

She was me. At the time, I was just 25 years old and the only young female Asian officer based at Limehouse station, and one of the small number of black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) officers who made up less than 1 per cent of the entire 28,000-strong Metropolitan Police Service (MPS).

After a heated dispute with our inspector, the Area Driver was eventually ordered to allow me to get into the passenger side of the car. He slammed shut his own door, put his foot down hard, and we set off on our patrol of the neighbourhood. He hardly spoke to me at all after we left the station, and I did my best not to irritate him any further by asking questions. I remember hunching myself up as far away from him as possible, pressing myself back against the seat to keep out of his eyeline.

Our patrol continued in silence around the main highways of Bow and Limehouse but then, without warning or explanation, we turned off the A11 at Mornington Grove and headed towards some of the unlit side-streets. I was curious but didn’t dare ask what the Area Driver had in mind. A few minutes later, he stopped the car under the railway bridge in Eleanor Street.

It was a moonless night, and the grimy, graffiti-covered brick of the bridge made for dark and dingy surroundings. I had no idea why we’d stopped, but there was another car parked on the side of the road.

‘That motor over there,’ the driver said. ‘Looks like it might have been nicked. Check out the number plate.’ I told him there wasn’t enough light to be able to see from our distance, but he wasn’t having it. ‘Go over and take a closer look,’ he ordered.

I was reluctant at first, but he was very much the boss so I thought I’d better do as I was told. I opened the door, got out and started walking.

I was already feeling ill at ease, heading away from the light of the car and into the gloom, but suddenly I heard a powerful engine roaring into life behind me, and turned to see the Area Car setting off at high speed. Within a moment, I was alone in the middle of nowhere, plunged into almost total darkness, unable to see more than a few yards, in an area well known to be a crime spot. Just a few yards further along was a site designated for the travelling community, many of whom, at that time, lived as much outside the law as within it. I was terrified.

Unable to believe what was happening, I reached for my personal radio and pressed the switch to broadcast an emergency message, but there was no response. Now my concern was rising fast, so I tried again – nothing, but as I looked around it became clear that the bridge overhead was obliterating any chance of a signal. I was checking my bearings to determine which direction I should walk in when I heard footsteps approaching from out of the darkness. Within a few seconds, I could see two men coming towards me from the direction of the travellers’ site. Both were smiling, but their smiles didn’t look friendly.

‘Hey, are you on the game?’ said one, laughing.

I was, of course, in full police uniform, so the question was hardly a serious one.

‘How much will it cost us?’ asked the other.

I mustered my courage and told the pair to back off, but felt my voice catch in my throat. At only 5 foot 3½ inches tall, and of slight build, I felt very vulnerable in a dark street with no access to back-up, and no way to raise the alarm if I were attacked. My fingers closed around the grip of what seemed to be a very flimsy truncheon. I tried to summon up my most authoritative voice.

‘Don’t be stupid now,’ I said. ‘Just step away.’

The men were not impressed.

‘We could certainly have some fun with you,’ said one, and once again the two men exchanged looks and laughed.

I truly believed I was going to be assaulted or raped, and suddenly I had a visceral recall of the moment nine years earlier, when the man I’d only just met but been forced to marry, overwhelmed and raped me on our wedding night. I was just 16 years old. Now, here I was again. New on the job, new on this beat, unfamiliar with the area, and completely powerless and out of my depth. I turned and started running, and I ran and ran and ran, almost all the way back to Limehouse, with the peal of the men’s laughter echoing around my head.

The incident was only the latest – and most serious – in several months of my life as a probationary WPC (woman police constable), in which I had already been frequently punched and kicked during demos, abused in the street, and subject to everyday racism and discrimination at work. That same night I telephoned my friend Shabnam Chaudhri. ‘I’ve finally had enough,’ I told her. ‘I’m going to quit.’

‘No, you’re not.’ Her tone left no room for doubt. Then Shab reminded me of the agreement we’d made just a few months earlier as new recruits training at Hendon. ‘Don’t let the bastards grind you down!’

Next morning, still feeling shaken and upset, I went to find the inspector and told him what had happened. He was unsympathetic. ‘You could make a formal complaint if you like, but then again he’s the Area Driver and you’re just a nobody.’ Junior and inexperienced though I was, I already knew enough about the Met to understand that, no matter what injustice you might experience, you must never complain. Anyone who did could be ostracized, made the victim of dirty tricks or, worse still, denied back-up in case of emergency.

All that was thirty years ago, and by October 2019, when I resigned from the Met, I was a chief superintendent – making history as the first non-white female to rise through the ranks and achieve that status in the 189 years of the London force.

My time in the Met was full of incident – some of it positive, even comic, much of it disappointing – and I have had more than my share of tragedy. It’s been an extraordinary career in many ways, and as I began to see the end of it looming up ahead, several people told me I should write my life story. Kind friends pointed out that my journey from a family of immigrants who spoke no English to becoming the highestranking BAME female in the Metropolitan Police would be an inspiration to some and a revelation to many. I always shrugged off the suggestion – excusing myself by saying I didn’t have the time, had signed the Official Secrets Act, and anyway I didn’t think I was all that special.

There the matter might have rested, but what I didn’t know was that I had already made the mistake that would turn my career, and my life, upside down. It was a mistake I should have learned not to make all those years earlier – a mistake I’d warned others against making many times since. Nonetheless, it was a mistake that a number of black, Asian or minority ethnic police officers had made in recent years. Sick and tired of being bypassed, bulldozed or ignored, I had finally confronted a white senior officer about what I suspected was a breach of regulations, and from the moment the complaint was made, my professional life would never be the same again.

Suddenly, having broken through more glass ceilings than any other BAME woman in the Met, and having upheld the law the best way I knew how for nearly thirty years, I found myself accused of a series of charges of misconduct, gross misconduct, and even of breaking the law. False and malicious allegations were leaked to newspapers, and the force to which I had given loyal service above and beyond the call of duty turned its fire on me in a manner which seems so vindictive that it defies understanding.

But as incomprehensible as the story is, what happened to me follows a familiar pattern. When a black or Asian officer in the Metropolitan Police toes the line, keeps their head down and suffers racial and/or gender discrimination in silence, we are tolerated and can even thrive – up to a point. If and when any of us stands up and says, ‘I’m not having this,’ we instantly become subject to a systematic campaign of smears and persecution more fitted to the pages of Kafka. At the time of writing, no fewer than five of the six BAME officers of chief superintendent rank or above in the MPS are under investigation for alleged misconduct.

It didn’t have to be so. In London, 43 per cent of people are from a BAME background, and yet the police force seeking to serve this population contains only 14 per cent BAME officers. Given how under-represented black, Asian and minority ethnic communities are in its ranks, the Met could so easily have used my story as an example to encourage recruitment from among these groups. Instead, I found myself compelled to end my career by resorting to what would inevitably be a highly public and damaging employment tribunal, citing evidence of systematic and long-term discrimination on grounds of race and gender. To any black or Asian youth considering joining the Metropolitan Police Service, the message would be clear: Don’t.

My eventual decision to take my case to an employment tribunal didn’t come easily. It was the culmination of thirty years of enduring regular episodes of discrimination – many relatively slight and many breathtaking. Incidents have ranged from lowlevel sexual and racial abuse, which was so commonplace that it became part of my daily routine, to finding myself in the crosshairs of forces which seemed determined to thwart any promotion, or even to drive me from the service altogether. It’s a story which many people might find unsettling, but it should not be surprising, because my life in the police has been conducted against a background of seemingly never-ending reports from public inquiries, parliamentary select committees, the Commission for Racial Equality (CRE) and the Equality and Human Rights Commission, among others – all of them highly critical of racism in the Met and exhorting the force to do better. More than two decades after the Macpherson report into the murder of black teenager Stephen Lawrence branded the Metropolitan Police Service as institutionally racist, most of the data and most of the experience demonstrate that little or nothing has been learned.

The evidence is stark. A young black man on the streets of England and Wales today is forty times more likely to be stopped and searched than his white counterpart. Officers in the Met are four times as likely to use force against a black person than against a white person. A black person driving a car is twice as likely to be pulled over and required to produce documents. In the event that someone from the BAME community should choose to join a force which many regard as the enemy, they are less likely than their white colleagues to stay the course. If they do stay, they are less likely than their white colleagues to achieve promotion to the higher ranks. They are twice as likely to be accused of misconduct and, once accused, are more likely to be found culpable. If accused, their names are more likely to be leaked to the media, which will highlight the charges alleged against them in bold headlines. If found guilty, they will receive more serious disciplinary sanctions than white officers. A higher proportion of BAME officers, sick and tired of the perpetual struggle, will give up and retire early. Or our careers will end with a rancorous employment tribunal.

All this means that, when the Met’s first female commissioner Cressida Dick claims that the force is no longer institutionally racist, as she did on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the murder of Stephen Lawrence, the facts very clearly say otherwise. The Chair of the House of Commons Home Affairs Committee, Yvette Cooper, described progress in dealing with the criticisms made by the Macpherson report as ‘glacial’. In light of the most recent discriminatory treatment of BAME officers, such as myself, even that depressing metaphor might seem to be over-optimistic.

I hope that the story of my early life, in a family whose customs were formed in a very different time and place, contributes to a wider understanding of the struggle undergone by hundreds of thousands of second-generation immigrants into Britain. I also hope that my account of the daily life of a police officer will encourage people to consider the price paid by any ordinary copper who dedicates themselves to serving the public. Most of all, though, I believe that my experience of finding myself on the wrong side of a police service still riddled to the core with institutionalized racism should make every one of us feel ashamed.

My story – and the stories of so many of my fellow BAME officers – is of a struggle against adverse odds. A good place to begin this particular tale is in the Punjab area of northern India nearly twenty years before I was born.

CHAPTER ONE

A Difficult Child

Both my parents, Malkit and Gurmaj, were born in the small village of Rurka Kalan in the Tehsil Phillaur area of Jalandhar in the Punjab. One day, sometime in 1951, a group of strangers arrived in the village carrying a message for the young men of the community. Any man willing to travel to the land of the former colonial ruler, they promised, would find work and would prosper, so that he would be in a position to send money back home to support his family. Since supporting the extended family was seen to be one of the main duties of the men of the Sikh community, there were plenty of volunteers.

My dad, Malkit, always told us he was chosen to come to Britain over any of his four brothers because he was known to be the hardest worker. He and my mum, Gurmaj, had been married by arrangement between their families when she was just 10 years old, and she’d given birth to their first child – my eldest sister – Jindo, while still in her teens.

Being an entirely rural community where everyone lived off the land, life was very hard. These were the years before investment in agricultural technology and developments in seed fertilizers boosted the production of wheat and rice in the region, and tilling the soil and the constant need for irrigation called for heavy manual labour. A woman bearing a son added a useful pair of hands to the joint effort, whereas a woman bearing a daughter simply introduced an extra mouth to feed. If that was not bad enough, there would later be the potentially huge expense of getting together a dowry, which must be provided when the girl came to be married. This would inevitably include a set of clothes, gifts for all the husband’s family, and something in gold – nothing less than 24 carats would do. Unfortunately for Gurmaj, she had two more children in quick succession, but one of them was another girl, Balbiro. The family of farmers had already experienced one of the deprivations of poverty in a land recently partitioned following independence from Britain; Jindo suffered from an eye infection as a child, and the failure to have it treated led to permanent blindness.

All of this was such a serious disappointment that some members of her community told Gurmaj she was worthless, and that the best service she could perform for her hard-pressed family would be to commit suicide. Taking her two daughters with her would reduce the hungry mouths by three. So great was the pressure on her that, one day, she took Jindo and Balbiro to the edge of the well in her village, and was at the point of throwing my two sisters and herself down. Just in time, she stopped and thought, ‘No, we are worth more than this,’ and decided to spare her own life and that of her two girls. It was a story from the past which she told me many times as a child growing up years later in Handsworth, and which I would have many occasions to bring to mind way into the future.

My dad was one of approximately 7,000 Sikhs from the region who came to Britain that year. No-one from the family today is quite sure how he managed it, but he travelled on an illegal passport in the name of Amar Nath, with a made-up date of birth. The village all contributed to the cost of the air fare on the understanding that they would be repaid from his future earnings, which eventually they were. Dad was immediately shipped to the Smethwick area of Birmingham, where he quickly got a job as a labourer at Birmid Industries. Birmid was an iron, aluminium and magnesium foundry, one of the largest employers in Smethwick, providing jobs to thousands of local people. It was hard, hot and dirty work, involving long hours and sometimes dangerous conditions – a million miles away from Dad’s harsh but essentially rustic life back in the Punjab. These young men worked six or seven days per week in fourteen-hour shifts. If, and when, they did take any time off, there was nowhere for them to go for relaxation or to practise their religion. They felt themselves abandoned in a country where they couldn’t speak to anyone other than fellow Indians, and they also couldn’t speak freely to each other at work because safety requirements meant they had to wear ear protectors.

It was tough to find somewhere to live because many of the local people didn’t want to rent rooms to immigrants. Signs on pubs and lodgings featured variations of ‘No blacks, no Irish, no dogs’, and Dad used to say that the British treated dogs better. Eventually he got a place in a shared house where he ‘hot-bedded’ with other shift workers. It was not unusual in those days for twenty-five young men to share a house, with those working on the night shift sleeping by day and those on the day shift sleeping by night. After a while, groups of men circumvented the system by pooling their resources to buy a house for one of them, who would then assist the others to buy the next house, and so on.

Conscious that his status as an immigrant might not stand up to the closest scrutiny, Dad was always terrified of authority. He’d been advised by others in the community that he should never look a white person in the eye, and always seemed to lower his head when he spoke to outsiders. That didn’t save him from encountering racism on his way to and from work, and in later years he told me that he and his friends were regularly kicked, punched and beaten by gangs of white youths, as well as by the police. One time he was knocked off his bike by a car and he apologized to the driver. It turned out that he had broken his leg, but Dad was afraid of doctors so wouldn’t go to hospital. The leg healed itself after a time but after that he always walked with a limp.

Despite having to shoulder the burden of taking financial care of a family he now never saw, Malkit made a decent wage for the times, and tried to make the best of his new life in a strange country. For the first time, he was independent and living far away from the tight religious observance of his homeland. Heavy consumption of alcohol became normalized within the community, especially among manual labourers, and local publicans eventually saw the opportunity to stage cabaret acts targeting the needs of young men living a long way from home. Within limits, my father became ‘one of the boys’, enjoying drinking beer and other freedoms. This went on for eleven years – until 1962, when the imminent prospect of new restrictions in the form of the Commonwealth Immigration Act meant it might well be ‘now or never’, and he was finally ready to send for his wife and children.

When Gurmaj arrived in Britain to join my father, Jindo was 15, my brother Faljinder was 13 and Balbiro was 11. None of them spoke any English, but by then Dad had managed to save enough money to put down a deposit on a small house in Tiverton Road, Smethwick.

Due to the shortage of manpower after the Second World War, Smethwick had already attracted a large number of immigrants from Commonwealth countries, and Sikhs from the Punjab were the biggest ethnic group. These minority communities were unpopular with many in the white British population of the borough, which had become home to a higher percentage of recent immigrants than anywhere else in England. The boom in job vacancies had proven to be short-lived, and in the same year that my mother and my older sisters and brother arrived from India, a series of factory closures and a growing waiting list for social housing caused race riots in the town. Just two years after that, in the 1964 general election, the Labour MP, shadow Foreign Secretary Patrick Gordon Walker, lost his seat on a 7 per cent swing to the Conservatives. His defeat followed a campaign in which the slogan ‘If you want a n––––– for a neighbour, vote Labour’ had been used in support of the winning candidate, Peter Griffiths. In his maiden speech in the Commons, Griffiths drew attention to the fact that 4,000 families in his constituency were in the queue for local authority accommodation.

Notwithstanding the prejudice prevalent in parts of the wider white society, my mum and dad lived in an area where all their friends and neighbours were from the same region of India, so they saw no reason to integrate with the host community, or indeed to learn to speak English. They also experienced no pressures to conform to the ways of their adopted country, so their thoughts quickly turned to arranging a marriage for their eldest daughter Jindo. The problem was that her blindness meant that making an advantageous match was not going to be a simple matter. Eventually the couple agreed that 16-year-old Jindo should be married to an older man from West Bromwich.

It was into this culture and mindset that Malkit and Gurmaj’s first child to be born in Britain arrived on 5 December 1963 in St Chad’s Hospital, Birmingham. They named me Parmjit but always called me Pummy, although my Western name was Parm as I got older. All my life, I’ve been told what a difficult child I was. My mother later described me as ‘the most miserable child ever’ and regularly said she wished she’d killed me at birth. Even today, I’m not completely sure whether or not she was serious.

I was followed by my younger sister Sarj in 1965, and my younger brother Satnam in 1966. With Jindo no longer living with the family, my parents and their other five children squashed into the two-up two-down house in Tiverton Road. The congestion was made worse because my dad, being the head of the family and still working shifts at Birmid, slept alone in one of the two bedrooms. This left my mother and the children to sleep together in the other, which had so many beds squeezed together that you had to jump from one to another. I remember that several of the beds were second-hand from hospitals, and there were no gaps to walk in between so the whole room looked and felt like a giant trampoline. The overcrowding was made still more difficult because we were seldom allowed to go into one of the downstairs rooms because it was ‘for best’. Despite the best efforts of my mum and dad, there were constant infestations of rats and mice. There were no carpets on the floors, which were covered instead with linoleum. The kitchen had stone flags and they used to drag in a tin tub from the back yard, fill it with hot water boiled on the stove, and all of us children would have baths on Friday nights.

There was no dining table, so all of us sat cross-legged on the floor to eat our food. Most of the plates had hotel names on them and were mismatched with enamel cups and bowls that had been bought second hand from the local market. Nothing in our house was new; there were no toys for any children and no celebrations for Christmas or for birthdays. Birthdays were said to be ‘for gurus’ (disciples of god), which we certainly were not.

I have a memory that everything was covered in brightly covered fabric which made it seem happy. My mum used to buy material at the local market, and she would knit or crochet covers for the furniture. She also had an old Singer hand-operated sewing machine, and so very little of our clothing was shop-bought, and was either homemade or handed down from siblings or neighbours. Four yards of multi-coloured material would be enough to make a complete outfit, consisting of a long dress, with matching trousers and a headscarf. Often, she would unravel jumpers and then reknit them for us, which was as close as we got to wearing new clothing.

The family had brought very few possessions from India other than a few old quilts. What they had brought with them was a strong culture which put the family at the centre of all aspects of life. Having lived as a Sikh minority in a region long dominated by Muslims, loyalty to the family was considered to be not so much a matter of social convenience, but more one of survival. A family’s esteem within our community was measured by its prestige and honour, or behzti, which in turn were a function of the family members’ izzat – their ability to garner wealth, especially land, but also the obedience and chastity of the daughters, for whom advantageous marriages must be procured.

Our house was separated from next door by a narrow alleyway, and on the other side of the divide was another family from the same area of India. Two of our neighbours’ children, known to us kids as Bubby and Juggi, were more or less my age, and so were natural playmates. No-one from the Indian community was given individual surnames at the time – all the men added ‘Singh’, meaning lion, to their names, and the women ‘Kaur’, meaning princess. As children, we’d play hopscotch and games of chase, but mostly we would ride our bikes around the block. Dad was always pretty useful at mechanical things, and made my bike himself from spare parts he’d managed to collect.

One day, the people next door had a telephone installed, which was a rare and amazing thing, so there was even more traffic across the alleyway. Family members were constantly going back and forth, making and taking calls with friends and relatives from the locality or sometimes from the sub-continent.

I also remember that Dad brought home an old black-andwhite television which was propped up high on a cabinet. Needless to say, there was no remote control, so the children had to climb up if we wanted to change the channel. I enjoyed The Man from U.N.C.L.E., Blue Peter and cop shows like Starsky & Hutch, but I wondered why the programmes featured so few people who looked like me, unless of course they were criminals. We could never find the right place for the aerial, and so my younger sister Sarj would be required to stand and hold it in position above her head –a grievance I don’t think she’s forgiven to this day.

Dad was still working long hours and incredibly hard, and occasionally we’d go to visit him at the foundry at the weekend. We were mesmerized as we watched our father wearing a protective mask and goggles, while hot sparks flew all around him and molten metal was poured nearby. On Sundays, we would pick the fragments of metal out of his work-clothes.

Apart from cutting his hair and shaving his beard for reasons of safety at work, Dad’s only real concession to integration was to abandon the turban which was so emblematic of the Sikh faith of his forefathers. Many of his contemporaries preferred not to follow suit, and in August 1967, just down the road in Wolverhampton, a bus driver named Tarsem Singh Sandhu (no relation) returned to work after a period of sick leave wearing a turban. He was sacked for failing to observe rules on uniform, and subsequently some 6,000 Sikhs marched through the streets in his support. There were significant signs of a white backlash, and a letter appeared in the local paper in which the correspondent claimed, ‘It is time they [the Sikhs] realized this is England, not India.’ After two further marches, the leader of the local Sikh community, Sohan Singh, declared his intention to set fire to himself on 13 April if the Wolverhampton Transport Committee did not change its policy. Four days before the deadline, the Mayor of Wolverhampton, describing the threat as blackmail, reluctantly gave in, having been ‘forced to have regard to the wider implications’.

Meanwhile, our dad still liked a drink and loved music, playing the radio for much of the time, and also kept a reel-to-reel tape recorder with Indian music for special occasions. I suspect he was ‘a bit of a lad’ during his time in England alone, but once our mum and his children and responsibilities arrived, he struggled with depression. Later, as I was growing up, he was in and out of a number of mental institutions, and I vividly recall the trauma of standing outside a treatment room as he underwent various rather primitive ‘electro-therapies’. For the moment, though, his wage was steady, and so our parents began to allow themselves a few luxuries. Mum’s pride and joy was a highly ornate tea-set with gold detailing, bought at the market for £20, which was a week’s wages. It was kept in a display cabinet and only used once or twice a year for special occasions.

It was soon very clear to the family that I wasn’t conforming with the quiet, unassuming and almost invisible role traditionally played by young girls from the Sikh community. I would speak without waiting to be spoken to, and would not readily merge into the background, allowing my brothers to take centre stage. I was always wanting things, and continuously getting into trouble. (A prized china dog which was kept on a window-ledge was mysteriously broken and the culprit has never been identified to this day.) Nonetheless, I was entrusted to walk to the off-licence on the corner of the road carrying a two-pint glass jug which would be filled with mild ale and carried home for my dad. Mum used to manage all the money, and on Friday nights she would give Dad a small amount for beer at the pub, and then he would bring back a bag of chips.

On Saturday mornings, Dad would walk me down to Smethwick library. Although he still spoke no English himself, and the whole family spoke only Punjabi at home, he ensured that all three of his British-born children had learned the English alphabet before we started at primary school.

Later, the house in Tiverton Road was the subject of a compulsory purchase order and our family moved a mile and a half to 22 Paddington Road, Handsworth. Another tiny terraced house, but this one had three steps from garden gate to front door, and three upstairs bedrooms. Still, every Saturday, Dad would walk me, and later also my sister and brother, to the library. He would never come in with us, preferring to wait outside whatever the weather, feeling that his working clothes were not suitable. The librarian once said to me that he could come in and wait. I went out and told my dad, but he said that people like him couldn’t go into places like that. He didn’t complain, even if we took a long time choosing books.

I spoke some limited English when I first went to school at Parkside Infants in Smethwick, but it hardly mattered because most of the community was Indian. Although the lessons were in English, all of us children spoke Punjabi to each other. Gradually, as we learned more English, my younger brother and sister and I began to speak it among ourselves, but our mother would tell us off – believing, often correctly, that we were talking about her. Since almost everyone around us was Indian, and since we girls in particular were being raised to be obedient wives and mothers and seamstresses, what need of English?

Looking back on it now, I think my dad feared and revered education at the same time. He loved books and, despite his own lack of formal schooling, always made us wash our hands before reading and never allowed us to put them on the floor or bend back the spines. He knew that it was his own lack of education which had led to him being at the lowest strata of society. He also respected the one good English speaker in the row of houses who knew enough to deal with official correspondence on behalf of all the neighbours. Most streets would also nominate one person who’d go to register things like births and deaths, and would fill out any forms in English.

In some ways, it seemed as though a whole community of people with the same culture, language and religion had been lifted up wholesale and transplanted to the heart of industrial Britain. Apart from the dramatic change of weather and the regular work in factories, shops and offices, very little about their personal and family lives had changed. The reluctance of the immigrant community to integrate, coupled with the racism which accompanied shortages of jobs and housing, were jointly the cause of the often poor relationships between the local indigenous people and the new arrivals.

It was this tension and disquiet among the local population which gave rise to one of the most notorious episodes in the history of race relations in Britain. In April 1968 – the same year that I was starting school just down the road in Smethwick – Tory MP and shadow cabinet member Enoch Powell made a speech to the local Conservative Party in Birmingham. In it, Powell was strongly critical of the recent bouts of mass immigration, especially from the Commonwealth. Always a melodramatic orator, Powell quoted a line from Virgil’s Aeneid: ‘As I look ahead, I am filled with foreboding; like the Roman, I seem to see the River Tiber foaming with much blood.’ His address became universally known as the ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech. Powell’s argument caused a storm of controversy, and Tory party leader Edward Heath reacted strongly to the accusations of racism and dismissed Powell from his shadow cabinet.

It was 1968. Students in Paris were rioting in favour of academic reform and civil rights activists in America were following Martin Luther King just ahead of his assassination. In Britain, anti-war demonstrators were clashing with police in front of the American Embassy in Grosvenor Square over Vietnam, but the biggest marches were by East End dockworkers taking part in spontaneous demonstrations in support of Enoch Powell. Some people believed that the popularity of Powell’s doom-laden prophecies was a major contributor to the Tories’ surprise win in the 1970 general election.

Even though I was only 5 years old, I have a hazy memory of the controversy and concern caused in our community by Powell’s speech. At the time, though, I had more important things on my young mind because I was beginning to enjoy my education at Parkside Infants. I loved school from the first day and was good at every subject: books, sums and sport, especially cross-country. My first reports were positive about my work in class, but would say things like ‘wilful and forceful’. As one of six children, I had to be those things if I was to have any chance of being heard.

Already I was showing more and more signs of being unwilling to conform to the culture and manners my parents had brought with them from India. One of my friends was a girl from a lower caste, a chamar. Chamars were traditionally considered to be leather-workers, and (worse still) landless – outside of the Hindu ritual ranking system of castes, so-called ‘untouchables’. It’s widely believed that Sikhs don’t observe the caste system, but they absolutely do, and many of them also discriminate based on the lightness of your skin and how tall you are. One day some of our relatives living a few streets away saw me speaking to my friend and reported the scandal to my parents. Later that day, I was severely chastised for bringing shame on the family. Needless to say, I defied them and kept my friendship.

I remember one day feeling curious about the reason my father had signs of piercing in both ears. He explained that when he was a child, during the partition of India in 1947, small boys from his community would be taken and murdered by Muslims, but girls were left alone as being hardly worth the effort. His parents disguised him as a girl to keep him safe, piercing both ears as part of the subterfuge. The underlying message, that girls were seen as so insignificant that it wasn’t even worth the effort it took to murder one, didn’t go unnoticed. All his life, my dad told me to ‘stay away from Muslims’, which was another warning I cheerfully ignored.

The fear of persecution, which had haunted my mum and dad’s lives as children, continued to be fed by events in the wider world. In early August 1972, the President of Uganda, Idi Amin, ordered the expulsion of his country’s Asian minority, giving them ninety days to leave. Many of those expelled had links to Britain, and more than 27,000 arrived here in the UK, leading to further public disquiet and sometimes violent demonstrations on the streets of major cities. Whenever something happened in politics or an immigrant was threatened, beaten or killed, everyone would gather at one of the houses to decide what they should do and how to stay safe and away from trouble.

My parents were never allowed to forget that this was not truly our home, and that we were not welcome. They believed that the British would also kick them out when they no longer needed the workers or when they got too old to work. My dad and the community felt that if one of you had a British passport you could fight for the right to stay, but if you were both Indians you would be deported. They did not want to end up stateless so my mum always kept her Indian passport.

They felt they had to own their own home to make sure they had a place to stay, where they were relatively safe, but their houses were always in rundown areas and in a poor state of repair. We had locks on all the exterior and interior doors, which made the rooms feel a bit like panic rooms. Even the staircase had doors fitted at the top and bottom, and both were bolted from the inside in case anyone got in. They had to protect themselves, because they would not call the police under any circumstances.