9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Oldcastle Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

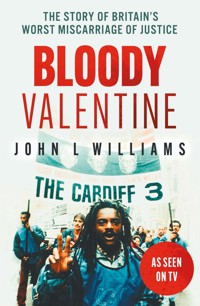

Bloody Valentine is the story of the murder of a young woman called Lynette White in the Cardiff docklands (aka Tiger Bay) on Valentine's Day 1988. It's also the story of the miscarriage of justice that came after, when three black men, 'the Cardiff Three', were wrongly convicted of her murder. It's a brutally frank tale of racism and police corruption, terrible misogynist violence and the grim realities of sex work. It's a book that got so close to the bone that the author was sued for libel by the police and received death threats from a variety of minor characters. It's an indelible portrait of life in the underbelly of Thatcher's Britain. This new edition includes an introduction and afterword bringing the extraordinary, unhappy saga up to date.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 348

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Critical Acclaim forBloody Valentine

‘This miscarriage of justice happened in Cardiff, but we felt it in Birmingham, Manchester, London, Glasgow, and in towns and cities all over Britain. John L Williams has given us a true and detailed account of this horror story. Sadly, he didn’t make this up. This is a real horror story. Bloody Valentine is a bloody good book!’ – Benjamin Zephaniah

‘Complex, emotional, moving. Read it’ – David Peace

‘A sharp-edged social inquiry as much as a crime story’ – Guardian

‘A powerful and gripping investigation… has all the narrative drive of a good thriller’ – Yorkshire Post

‘Bloody Valentine shows Williams’ impressive eye for detail to its best advantage’ – Arena

Critical Acclaim forThe Cardiff Trilogy

‘Cardiff has never been so vibrant as in Williams’ seductive and strangely moving novels’ – Sunday Times

‘Williams’ writing animates the city in much the same way Nicholas Blincoe managed with his Manchester novels and Armistead Maupin with his tales of San Francisco’ – Time Out

‘Williams has an extraordinary imaginative grasp of under-represented minorities’ – Guardian

‘The sheer liveliness of the stories, which fizz with pace and energy, makes for a really entertaining and intriguing account of life on the mean streets of Cardiff’ – Times

Critical Acclaim forMiss Shirley Bassey

‘A fascinating history’ – Daily Telegraph

‘Sensitive and empathetic… lovely details abound’ – Guardian

Critical Acclaim forMichael X: A Life in Black and White

‘An absorbing book that adds up to rather more than one life…

There are excellent descriptions here of street demos and wild parties that have the authentic note of the times’ – Times

‘[An] engrossing biography… That this is also a story told with compassion makes it all the more readable’ – Independent

Contents

Introduction to the Second Edition

Introduction to the First Edition

one

two

three

four

five

six

seven

eight

nine

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

For my parents, David and Gillie Williams, with thanks

Introduction to the Second Edition

When I wrote this book, nearly thirty years ago, the world was a different place. A less connected place, a pre-internet world in which news came from papers and TV bulletins, in which people who lived in London knew little of the lives of people in Cardiff, for instance. It was a world, too, in which the police were almost universally trusted, and in which racism, sexism and homophobia were simple facts of life.

Thirty years later you can read this book on a computer and, if you’re so minded, find photos and videos and Wikipedia pages to enhance or fact check what you’re reading. If you, a Londoner, want to know what’s going on in Cardiff, you can read news pages and restaurant blogs, join Facebook groups or take a virtual walk around its streets with Google maps. There is little mystery left.

In some ways, at least, this has led to progress. The old prejudices are in retreat. No one would claim that racism, sexism and homophobia have vanished, but they are far less generally acceptable than they were. And greater scrutiny has made sure that no one, not even the police, is granted our unquestioning trust.

And yet, despite all these changes in the wider world, the story of Lynette White and the Cardiff Three is still not over. The legal proceedings finally ground to a halt in 2016, 28 years after Lynette’s murder, but no one is satisfied that justice has been done. The full sorry history of all that litigation is addressed in the afterword to this edition.

The essential facts, however, continue to speak for themselves. In late 1988 five black men were arrested for the murder of Lynette White. The killer’s blood was on Lynette’s body, and it matched none of these five men, but the police still brought the prosecution. It is perhaps even more shocking that a jury convicted three of the five. But then this was a Swansea jury at a time when Swansea people knew little of black Cardiff docks people, for all that their community had roots stretching back a century. And the natural tendency was to believe the police were telling the truth. As with the Birmingham Six and the Guildford Four before them, the Cardiff Three were convicted despite the total lack of evidence against them, quite simply because they looked the part. Not Irish Catholics this time, but black men with criminal records. The same prejudice that got them arrested saw them convicted.

This book tells the story of how this sorry saga unravelled. It’s a story of racism that was truly institutional, but not simply a story of racism. The people of Butetown are and were unusually racially mixed. The subset of that community that this book mostly deals with – the hidden underclass of prostitutes, drug dealers, pimps and petty criminals – particularly so. The prejudice that powered this story was not simply racial, but was directed against those who society deems beneath consideration, and treats without compassion. That specific world described in this book may be largely a bygone one, but the prejudice against those at the bottom of our society lives on.

This book is the story of events that changed many people’s lives, almost exclusively for the worse. Writing it didn’t change my life much in the material sense, but in other ways it changed me profoundly. I had thought I knew how the world worked, and I realised I knew nothing. I immersed myself in the detail of the everyday lives not just of the prostitutes and drug dealers, but also the struggling families for whom some level of criminality was essential just to survive, and for whom prison visits were a way of life; the people who never answer a knock at the front door, because everyone you trust knows to come round the back. The experience of writing this book lifted the veil from my eyes. It took away, appropriately enough, my innocence. I understood in a way I never had before that, for too many people, this world is not safe or decent or fair. And in the writing, I hope I have communicated something of that new understanding.

Introduction to the First Edition

On 14 February 1988, the dead body of a twenty-year-old Cardiff prostitute, Lynette White, was discovered by her friend and colleague, Leanne Vilday, in a semi-derelict flat above a bookie’s in Butetown, Cardiff. She had been stabbed more than fifty times and had been lying there since the previous night.

In a way it was an ordinary murder, awful but ordinary. In another place and at another time it might have passed almost without comment, apart from the legacy of grief left to those who’d known her and whatever consequences God or justice may visit upon her killer.

But this murder didn’t go away. Lynette White’s death set in train events that were to change both the people who knew her and the neighbourhood in which she died, the place they once called Tiger Bay – events that have changed the world she lived in, almost beyond recognition.

This book is about what happened to Lynette White and about what happened to Butetown, what happened before and what happened after, and it’s an attempt to explain why her death scarred so many lives.

one

The Lonesome Death of Lynette White

It was raining and shewas in Despenser Gardens. Always seemed to rain in bloody Despenser Gardens. Three days she’d been back there. And she’d thought she’d never have to. Crichton Street was better. You could sit in the Custom House and have a warm and a laugh. Can of Breaker and a spliff, maybe get a line from Leanne if you’re too knackered. Here there’s just the Coldstream and she didn’t even want to go in there in case she saw someone she knew. Saw her dad there once, first time he saw her working. He nearly died, the old bastard. Out on the piss with his mates, he had to pretend he didn’t know. Of course he bloody knew. Do me a favour, he bloody knew all right.

Still, she was safe enough here. Stephen was too fucking stupid to figure out she’d be here. He’d be looking for her in the North Star. Maybe he’d go to the Custom House, but he wouldn’t think of coming over here. And it was off fucking Francine’s fucking family’s turf too, thank Christ. Why she’d talk to the law about Francine she couldn’t bloody imagine. Now she’d opened her big mouth and she was due in court to testify against Francine bloody Cordle. Nah, fucked if she was going to court to get into that kind of shit, stay out of the way for another week and she’d be all right.

Jesus, it was wet though. Maybe she could go round to Michael’s on the Embankment, cup of tea and a spliff, maybe buy another ten-quid deal. Except she might see Nicola or one of them over there. Shit. Been out for two hours and made fifteen fucking quid. Wanked off a Paki in the alleyway, and then a blow job in an Astra. Christ, she could still taste him, mixed in with the chicken and chips. Oh, stop thinking about it and just do one more and then call it a night. Buy some cans and get blocked enough to sleep. Just a few more days and she’d get it sorted. Get it all sorted.

Second time this one’s come by, looks like a student, looks like I’ve seen him somewhere. God knows, I’ve seen enough of them before. Jesus, he looks nervous. You looking for business? Don’t have a heart attack, for fuck’s sake. Ten pounds outside, twenty pounds in, get out of this pissing rain. All right, inside is it, you’ve got a car have you?

In the cab she could see him better, floppy fringe and shaking like a leaf, older than she thought too, more like thirty-five than twenty, looked like a student but too old. Good looking, if you liked that sort of thing, which she didn’t much, but something a bit, a bit, a bit like a young person with an old person’s eyes or an old person with a young person’s eyes. Something kind of off anyway, but what the fuck, twenty quid and hustlers can’t be choosers. Valentine’s tomorrow too. Stephen had wanted to take her to see his mother. So he said anyway. But what she was going to do with him she didn’t know. She’d had enough of it. No fucking respect, like Paul said.

Out of the car at James Street. Christ, the place looked worse every time she saw it. Front door practically fell open. Up the stairs into the flat. Follow me into the front, love, the electric’s off but it’s lighter there. Sit on the bed, take your shoes off, that’s twenty quid then, ta, luv. Put that on now, which way do you want…

Which was when she saw the knife and she knew it was over, knew before she screamed that the fucking little ferret-face queer from upstairs wouldn’t help, knew her daddy couldn’t help, knew her mam couldn’t help, knew no one would fucking help. Knew Stephen couldn’t help and she knew that she’d loved him and she’d loved Mark and she’d loved them all and she’d loved all the black boys she’d let have her all those times, and she knew she’d never have a baby now.

And then he was killing her. He killed her quickly because he loved her too and he was so angry and upset the way she’d behaved to him. How could she do that? How could she say those things? He tried to cut her head off with one swinging smash of the knife and her throat just came apart and he knew she was dead and he just fell on her, started stabbing her breasts and stabbing and stabbing and, oh sweet Jesus, oh that hurt, he must have hit her bone with the knife and his hand slipped and he cut himself, cut his hand. Really deep, oh god, it hurt, and just now he really lost it, now he’d really killed the fucking bitch.

And five minutes later he saw what he had done and knew that he’d come in his pants and he got out of there and he was glad that it was late and it was dark and he was surprised that when he walked out of there no one was waiting for him. But as he walked to his car he thought, it’s all right. No one fucking cares.

Leanne had brought three Pakis back to the flat. She did two of them herself but then the baby started crying and she had to get Angela to do the third. And then in the middle of all this shit in came Maria, Paulie’s missus, and she was screaming bloody murder about little Ryan not being for Paulie and Leanne told her to shut her fucking mouth ’cause he’s my boy’s father and then Maria chased her into the bathroom and hit her in the eye with her red, white and blue umbrella and there was blood all over the place.

And when all that shit finished and Maria and the punters left, Leanne had a black eye and bruises all over her face and Angela says you’re not going out looking like that but Leanne does another line of speed and says fucking hell I am, I’m going over the North Star for a drink. And Angela goes oh I’m looking after Ryan, am I? and Leanne says I fucking pays you, don’t I, and out she goes.

But before she gets to the North Star she looks up at her flat over the bookie’s, sees the front door open and the speed kicks in and says what’s happening here then, why not see if Lynette’s there, see if she’s all right. And in she goes and pushes the flat door open which you don’t have to be fucking Frank Bruno to manage and blocked as she is she knows it, she smells it before she sees it, but maybe it’s the speed that stops her from being sick. Though when the little queer came down he went white fast enough and ran back up looking as sick as a dog. But the speed just said get out of here. Get fucking out of here, you don’t want anything to do with this, oh Jesus, it’s my flat. Oh Jesus, Lynette’s dead in my fucking flat.

And she runs back over the road and gets Angela and they try to move the body, try to take her outside but that’s a stupid idea, she’s just too fucking heavy. So she just told the queer to shut his mouth and went back to Angela’s and she felt like she was going crazy, so she went over to the North Star. And she was just in time, half past three, Ronnie was there and thank Christ for that. So she went back to his sister’s but she couldn’t shake it, she kept talking about Lynette like a silly cow. And at 6.30 she couldn’t stand it and told him she was going home. He couldn’t care.

two

The Legend of Tiger Bay

Tiger Bay was the original pirate town. The way I heard it as a child, the real old-time pirates, Captain Morgan and his crew, used this promontory off the then small town of Cardiff as a base: a little piece of Britain that was beyond the law. God knows if it’s true or whether my addled memory has simply cobbled together a new myth out of two or three old ones, but still, it’s a legend that suits the wild side of the Welsh.

What we know for sure is that Butetown, not yet Tiger Bay, came out of the Industrial Revolution: in the 1840s the Marquis of Bute ran a railway from the new mines of the south Wales valleys to the Bristol Channel, coming out at Cardiff, by the mouth of the River Taff. Huge new docks were built at the end of the promontory, and the nascent city spread south to meet them. They called this settlement between the docks and the town Butetown, after the man whose coffers it was filling. And from the beginning the arrangement of railway lines, Bristol channel and river was such that there was a natural division between Butetown and the rest of Cardiff.

In those early days, though, Butetown was the heart of Cardiff. Mount Stuart Square, at the entrance to the docks, was the city’s commercial hub and Loudoun Square, in the heart of Butetown, was among the city’s smartest addresses, boasting a Young Ladies’ Seminary as well as providing a home for the shipwrights, builders, master mariners and merchants, the new aristocrats of a seafaring city.

The second half of the nineteenth century saw Cardiff expand at a breath-taking rate. By the end of the century it was one of the world’s biggest, busiest ports. The sheer numbers of ordinary seamen using the port forced changes in the area’s make-up. The smart houses of Loudoun Square, where my family once lived, were converted into seamen’s lodging houses, the merchant classes retreated into the main body of the city which soon sprouted smart northern suburbs, and the seafaring supremos, the ships’ captains and so on, congregated around the southern tip of the island, in smart streets like Windsor Esplanade.

By now Butetown was home to a fair cross-section of the world’s seafaring peoples – Chinese, Lascars, Levantines, Norwegians, Maltese, Spaniards and all. A wild and licentious community was emerging, finding worldwide fame as ‘Tiger Bay’. Black seamen too, both from East Africa and the West Indies, were a part of this cosmopolitan mix, the first of them arriving as early as 1870, and by 1881 being numerous enough to have their own Seamen’s Rest. By the time of the beginning of the First World War, there were around seven hundred coloured seamen in Cardiff, though this was still a mostly transient population of men without families.

The war changed everything. Many of Tiger Bay’s citizens joined the war effort. Seamen went into the Navy and Merchant Navy. The Western Mail reported, in 1919, that fourteen hundred black seamen from Cardiff lost their lives in the war (which also demonstrates the somewhat unreliable nature of the era’s statistics – there having allegedly been only seven hundred black people in Cardiff). Others joined the Army, the West Indian regiments or the Cardiff City Battalion. A Mr Rees recalled, in the South Wales Echo, that: ‘All the boys of military age joined up and most of them paid the penalty, some at the Dardanelles, and a lot with the Cardiff City Battalion at Mametz Wood.’

Conscription into the Army also left a huge gap in the domestic labour force and, at the same time, East African trading ships were being requisitioned for the Navy, thus leaving a pool of unemployed sailors. So in Cardiff, as also happened in Liverpool, factory jobs were opened up to the seamen. Unsurprisingly, now that they were based in Cardiff for a substantial period of time, the sailors began to put down roots and to make the first moves towards an integration into the wider community – one aspect of which was the forging of relationships with local women. This last development foreshadowed the GI bride phenomenon of the Second World War, except for the crucial distinction that this time the exotic suitors were not intending to whisk their brides across the ocean, but were planning to stay put in Butetown.

Trouble came with the war’s end. The soldiers returned, unemployment loomed. Black workers were thrown out of their factory jobs, and seafaring work was likewise in high demand. Black unemployment rapidly became chronic and meanwhile general white unemployment became one of the key issues of the day. In some cities, notably Glasgow where John Maclean, ‘the British Lenin’, held sway, the whiff of communist revolution was in the air, and the government was briefly terrified. In sea-faring cities like Cardiff and Liverpool, however, the racial minority was fitted up for the role of scapegoat.

Racial tensions first began to appear amongst the returning soldiers. Peter Fryer, in his remarkable and ground-breaking history of the black presence in Britain, Staying Power, tells the awful tale of an incident in a veterans’ hospital in Liverpool in which five hundred white soldiers set upon the fifty black inmates, many of whom were missing at least one limb. A pitched battle was fought with crutches and walking sticks as the principal weapons (though not all the white soldiers sided with the racists: a contemporary account, in the African Telegraph, records that ‘When the [military police] arrived on the scene to restore order, there were many white soldiers seen standing over crippled black limbless soldiers, and protecting them with their sticks and crutches from the furious onslaught of the other white soldiers until order was restored.’).

If the Belmont Hospital affair had an element of cruel farce, much of what followed was tragic. In the summer of 1919, in South Shields and Liverpool and Cardiff, Britain’s first race riots of the modern era broke out. The post-war slump provided the conditions for these mass outbreaks of racist violence – and Fryer clearly demonstrates that these riots consisted of white mobs randomly attacking blacks – but it was generally sex that provided the flash point. The returning troops could easily be goaded into believing that ‘their’ women were being stolen. Whites would repeatedly claim, as justification for assault, that blacks had been ‘making suggestive remarks to our women’ or some such. And the newspapers were swift to follow this line. Fryer records a Liverpool Courier editorial pontificating that:

One of the chief reasons of popular anger behind the present disturbances lies in the fact that the average negro is nearer the animal than is the average white man, and that there are women in Liverpool who have no self-respect.

The 1919 race riots were not simply regrettable occurrences from far-off days but rather the crucible in which Britain’s subsequent racial pathology was formed. The cry for tribal solidarity to protect their jobs from these ‘outsiders’ was overlaid with sexual hysteria: not simply ‘they’re taking our women’ but ‘they’re taking our women because they’re sex-beasts’. This hysteria presumably arose from a combination of black people having long been caricatured as apelike or bestial, and the legacy of Victorian prudery that regarded sex as a bestial activity. Certainly what emerged was the potent construction of blackness as both an economic and a sexual threat.

According to Fryer the flash point of the Cardiff riot on 11 June 1919 was, ironically enough, ‘A brake containing black men and their white wives, returning from an excursion, attracted a large and hostile crowd’. However, a recently unearthed account, written by a policeman present at the time, gives a rather less genteel and more detailed account. According to PC Albert Allen (as reprinted in the South Wales Echo):

I was the only PC on duty at the Wharf when it started and I was on duty the whole time it lasted in the Docks area. First of all I would like to point out the cause. In Cardiff there were quite a number of prostitutes and quite a number of pimps who lived on their earnings. When conscription came into force these pimps were called up. Then a number of prostitutes went to the Docks district and lived with these coloured people who treated them very well. When the war finished the pimps found their source of income gone as the prostitutes refused to go back to them. The night the trouble started, about 8.30 p.m., a person who I knew told me to expect some trouble. I asked him why and he explained that the coloured men had taken the prostitutes on an outing to Newport in two horse wagons and that a number of pimps were waiting for their return.

Next, by Allen’s account, the pimps attacked the wagons near the Monument – at the edge of the city centre and fifty yards or so from the Bute Street bridge which signals the beginning of Butetown – and a pitched battle ensued before police reinforcements dispersed the crowd and attempted to cordon off Butetown. What was by now an angry white mob, among them many armed demobilized soldiers, then proceeded to rampage around the town looking for blacks to assault. Some managed to get past the police lines and into Butetown, where they smashed the windows of Arab boarding houses.

This initial disturbance petered out around midnight, but the rioting was to continue for several more days. On the second day a Somali boarding house in the centre of town was burnt down and its inhabitants badly beaten. More boarding houses were then burnt down in Bute Street, and an Arab beaten to death. On the third day a white mob gathered once more in the centre of town and prepared for another assault on Butetown.

This time, however, Butetown was ready for them. If its position on an isthmus at the bottom of the city made Bute-town a convenient ghetto, it also made it a fortress. There was only one easy way in from the town centre, via Bute Street itself, and the other approaches, from East Moors and Grangetown, could be easily watched, so armed sentries were posted – the blacks too having brought their weapons home from the war – and the community waited. As a South Wales News reporter saw it on 14 June 1919:

The coloured men, while calm and collected, were well prepared for any attack, and had the mob from the city broken through the police cordon there would have been bloodshed on a big scale… Hundreds of negroes were collected, but these were very peaceful, and were amicably discussing the situation amongst themselves. Nevertheless, they were in a determined mood and ready to defend ‘our quarter of the city’ at all costs… Long-term black residents said: ‘It will be hell let loose if the mob comes into our streets… if we are unprotected from hooligan rioters who can blame us for trying to protect ourselves?’

Their defence was successful and the rioting died away over the next few days, leaving in its wake three dead and many more injured, but a decisive corner had been turned. The authorities’ only response to the troubles was to offer to repatriate the black community. Around six hundred black men took up the offer within the next few months, though many of the returning West Indians went back with the express intention of inciting anti-British feeling. And, indeed, within days of some of the Cardiff seamen returning to Trinidad, fighting against white sailors broke out, followed by a major dock strike.

The majority, however, decided to stay on, to make a permanent home on this ground they’d fought for. But from this point on Butetown was not simply a conventional ghetto or a colourful adjunct to the city’s maritime life, but effectively an island. It was not simply a black island: the area had always had a white Welsh population and continued to do so, there was an Irish presence too as well as Chinese, Arab and European sailors, and refugees from successive European conflicts as well. And as the black or coloured population was initially almost exclusively male, Butetown rapidly became a predominantly mixed-race community, almost unique in Britain, the New Orleans of the Taff delta, home of the creole Celts. But this integration was firmly confined to Tiger Bay: above the Bute bridge you were back in the same hidebound old Britain.

The following twenty years before the next great war did nothing but further entrench the racial segregation. What soon became known as ‘the colour bar’ came down to deal with black immigration. Industry was almost entirely closed to blacks and seafaring jobs were made ever harder to obtain by cynical manipulation of nationality laws. In Cardiff, the police arbitrarily interpreted the Aliens Order of 1920 to mean that any coloured person was de facto an alien. If they produced a British passport to prove otherwise that would simply be seized and thrown away. And, as if times were not hard enough already, the slump of 1929 simply saw economic matters go from bad to worse.

So, trapped as they were between the bigots and the murky green sea, the people of Butetown had to construct their own economy, based on catering to the traditional desires of men who have spent the last few months on the ocean wave. The community that emerged, though economically deprived and rife with disease, was possessed of a vitality that is remembered with great fondness by virtually all those who lived there in the inter-war period. Harold Fowler was born in Butetown in 1905, the son of a West Indian seaman and a Welsh ship captain’s daughter. Talking to the South Wales Echo in 1970 he recalled that ‘Bute Road used to be like St Mary Street. It had jewellers’ shops, restaurants, big poultry stores, laundries, music shops… There was always lots of music in Tiger Bay. The sailors and the prostitutes used to drink and dance in the pubs and cafés. And there was Louis Facitto’s barber shop. He had an automatic piano with bells and drums attached to it. You put a penny in and it played to you.’

Noise, though, was always one of the community’s defining characteristics. Mrs Bahia Johnson remembers in her unpublished memoir of living in Tiger Bay in the thirties, ‘On almost every door there were cages with screaming parrots and cockatoos. Were they able to talk! Believe me they put many a seaman’s language in the shade. Many people were forbidden to put them outside their homes. Tiny canaries sang in their little cages. There were men with little monkeys on their shoulders. They wore little red hats and gloves. Often a barrel organ would be wheeled around the streets with a little monkey on top. In the Roaring Twenties Bute Street was like a Persian market…’

Tiger Bay’s landmarks were its pubs. Eleven of them crammed into the neighbourhood: The Freemason’s Arms (better known to one and all as the Bucket of Blood), the Rothesay Castle (or House of Blazes), the Adelphi Hotel, the Loudoun Hotel, the Glamorgan Hotel, the Bute Tavern, the Peel Hotel, the Cardigan Hotel, the Bute Castle Hotel, the Marchioness of Bute and the Westgate Hotel.

Wally Towner, long-time landlord of the Freemason’s, admitted that its nickname was not undeserved:

We had some tough times down there all right. It was nothing for a couple of pounds’ worth of glasses to go in one night. I had a shillelagh behind the bar and I used to use it now and then. There was a big coloured girl there. She could knock a man out and would think nothing of it. She came to my rescue many times. One night there was a brawl in the smoke room. One chap was out on the floor. She’d given him one. I got a siphon and squirted it in his face.

That was a general occurrence. If they fought in the pub you just had to wade in and take a chance. Once one of the prostitutes saved my life. She took off her stiletto shoe and hit them over the head while I got up. There were the girls there of course. They lived for the day, they would make a lot of money and live it up, but some mornings they’d come in with black eyes, the pimps had given them those if they hadn’t made enough.

The girls used to quarrel sometimes. One day I saw some of them fighting, clawing at each other. I put two in the gents’ toilet, two in the ladies’ toilet and I told them not to come out till they’d finished scrapping. ‘I’ll give a bottle of wine to the winner,’ I said. My pub was a great one for the vino, 6d a glass.

The police were marvellous down there. They didn’t always lock them up. They just used to take them round the back and give them a damn good hiding. They can’t do that today, poor fellows. And of course the boys used to come down from the valleys to see the place and see the girls. They were looking for trouble.

One of those Valleys boys, ‘Charlie’ as he called himself in the Echo, remembers his first visits to Tiger Bay:

I went down there first because it was such a contrast with my home town of Merthyr. Merthyr was very drab at the time. It was a distressed area. I joined the army in 1926 to get away from the place and they sent me to Maindy Barracks in Cardiff. On our nights out the more adventurous of us dodged the military police and went down Tiger Bay. There were honky-tonks from one end of Bute Street to the other. It was great, so gay and colourful. We were ‘seeing life’, as we called it. We went in the back rooms and danced with the girls…

The inevitable happened. I got caught and had a dose of detention. When I came out I decided to join with some of the real boys of the bay. I thought, ‘This is the life for me,’ and I sold my uniform to a docker. So I’d burned my boats good and proper. [A career in petty crime ensued until] two of us got caught in a tobacconist’s shop in Pontypridd and were remanded to await trial at the assizes. The girls visited us with cigarettes and tobacco. I got three months and naturally returned to my friends in the Bay. I was met at the nick gate and given a few bob and a good booze-up in the Freemason’s, the haunt of pimps, prostitutes, wide boys and queers.

But, like Wally Towner, Charlie had scarcely a bad word to say for the police of the time: ‘There was a comradeship. They were out to get us and we were out to get them. We had very great respect for each other. In those days we believed that if a copper and another fellow were having a go, let them have a go. But if three or four boys were beating up a policeman we’d go to his aid. And if three or four cops set on one man, we’d help him.’

And it’s the same story from old-time Bay cops like William Rees, who started out as a Tiger Bay copper in 1921, stayed there till 1941, and finally retired as Chief Constable of Stockport. ‘I made more friends down there than anywhere else, real genuine friends,’ he recalls. ‘The great thing was knowing how to speak to them. If you spoke officiously you could expect trouble. But if you treated them like a pal you got your evidence. Of course there was trouble now and then, but there was far more violence in other parts of Cardiff, such as Caroline Street and Wood Street.’

Butetown even had more flamboyant cops than the rest of Cardiff. Mr Rees remembers a detective called Gerry Broben: ‘He was a famous figure in his khaki breeches, leggings and trilby hat. And he always had a pipe. He used to walk around in uniform with a pipe in his mouth. Time was of no consequence to him. He used to roll up at half past ten or eleven in the morning but nobody knew when he went off duty. Maybe two or three in the morning. He was a fount of information. He always knew where to get it. He was always behind the curtains, so to speak.’

Butetown’s most celebrated curtains were those of the Chinese community. ‘From 190 to 198 Bute Street was all Chinese houses,’ recalls Harold Fowler. ‘The Chinese were great gamblers – and many of them used to travel down from their laundries in the Valleys to Tiger Bay to play paka pu, a kind of lottery game with numbers, and fan tan, played with shells.

‘At the back of one or two of those houses were opium dens. There used to be bunks in those rooms with curtains around them. In the middle of the room was a small table with a lamp and several opium pipes. A man sitting at the table would put a ball in the pipe and light it for them and then they used to lie down on a bunk and dream their dreams.’

Well respected though the police may have been, it was within the community that the real arbiters of right and wrong were found. Community leaders of real authority emerged. Chief among them were a West Indian boarding-house master called John Purvo, who became the local president of the Negro Universal Improvement Association, and Peter Link, known as ‘the King of the Africans’, another boarding-house master and a man noted for his diligence in fighting for the rights of black seamen.

In the late 1930s Tiger Bay was graced with the presence of a more celebrated black leader: Paul Robeson, the great American singer, actor and communist who came to Britain to appear in two films – Hollywood of course having little use for black men at the time, except as eyeball-rolling Stepin Fetchits – The Proud Valley and Sanders of the River. Butetown actor/writer Neil Sinclair recently contributed a fascinating memoir of Tiger Bay and the movies to an excellent series of ‘Bay Originals’ newspapers; he remembers that ‘Robeson found a welcome in Tiger Bay, where he made several visits to the Jason home on the west side of Loudoun Square. There he used to visit the African-American activist Aaron Mossell who lodged there.’

The film that brought Robeson to South Wales was The Proud Valley, a charming if unsurprisingly sentimental tale of a black seaman landing up in a Valleys mining village, overcoming prejudice to become a stalwart of the choir (Robeson remains an enduring favourite with the still mighty choirs of the Valleys) and ending up with the immortal line ‘we’re all black down the pit’.

Robeson was the only black face in The Proud Valley, but Sanders of the River called for two hundred and fifty black extras, and Tiger Bay provided many of them – including among them, remarkably enough, the future Kenyan revolutionary leader Jomo Kenyatta, then a penniless anthropology student living in London. Sinclair recalls, ‘Everyone knew the witch-doctor dancing wildly in the African village was Mr Graham from Sophia Street. And that was Uncle Willy Needham in the loincloth that he kept for years after. The little black baby Robeson held in his arms was Deara Williams. Deara went on to become an exotic dancer with an act including a boa constrictor. And we all waited for the “River Boat Song” to begin so we could all join in. “Iyee a ko, I yi ge de,” we would chant in unison with Paul and all the African boatmen. Some twenty years later you could often see a gang of Bay boys on a separated timber log, singing the “River Boat Song”, rowing across the lake of the timber float, a little south of west Canal Wharf.’

And then there was another great upheaval. The Second World War rolled around and once again black faces were grudgingly invited into the factories. Meanwhile Tiger Bay’s reputation was such that black American GIs would converge on Cardiff from all over Britain when they had some leave. So throughout the hostilities it was business as usual in the world of illicit leisure.

After the war, the decline of the shipping industry was a devastating blow to the community. It deprived residents of both seafaring jobs and the money brought in by visiting sailors. But still, for a while Butetown continued to flourish. Mass immigration from the West Indies began, and at first Cardiff was one of the major destinations, a place where newcomers could be sure of a friendly welcome – to this day Cardiff remains a haven for Somali refugees.

In the fifties a new arrival could stroll down Bute Street and find, in rapid succession, the Cuban Café, the Ghana Club, Seng Lee’s Laundry, the Somali People’s restaurant and Hamed Hamed’s grocers. The House of Blazes and the Bucket of Blood were still open for business. And, for a place to stay, there was, for instance, the Cairo Hotel, run by Arab ex-seaman Ali Salaiman and his wife Olive, a valleys Methodist who converted to Islam and whose five daughters, in true Butetown style, married an Arab, a Welshman, a Maltese, an Englishman and a Dutch Muslim.

One of the new arrivals was a young Trinidadian called Michael de Freitas, who was later to achieve brief fame as Britain’s apostle of Black Power, Michael X, and later still was to be hanged for murder, back home in Trinidad, under the name of Michael Abdul Malik. His autobiography, published in 1968, is unsurprisingly self-justifying and generally economical with the truth but it contains this fond reminiscence of life in Tiger Bay in the fifties:

The Bay was a world of its own, cut off from the rest of the city. A black world. It swarmed with West Indians, Arabs, Somalis, Pakistanis and a legion of half-caste children. In its food stores you could buy cassavas and red peppers and in the restaurants you could eat curries and rice dishes just like those in the West Indies.

The city’s black people, who mostly worked in the docks, were the sweetest people I’ve ever met in Britain. They had a real friendliness. Everyone seemed to be married to everyone else’s sister and they’d all sit on the doorsteps of their elegant, dilapidated old houses chatting and exchanging greetings… I usually lived with a half-caste family who cooked Trinidadian food and I would spend my time talking, going to the Friday night dance at the solitary dance hall, and watching the street gambling. This was illegal, of course, but even the policemen had grown up in Tiger Bay, and when they saw a crowd standing in a circle they’d know a couple of men were in the middle shooting dice and they’d stroll in the other direction. They very rarely broke up a game.