Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

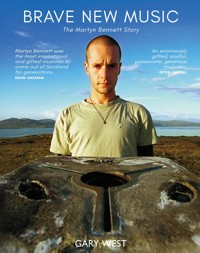

Martyn Bennett was an artist ahead of his time. Piper, violinist, composer, producer, DJ – his radical blend of tradition and technology created an audacious new sound that was uniquely his own. Steeped in the folk cultures of Scotland, yet inspired too by deep-rooted traditions from far beyond, his music ignored boundaries and celebrated cultural difference wherever he found it. Although classically trained, he was drawn to the gritty excitement of the urban dance club scene, and his fusion of folk, classical, jazz and hard-edged electronica was championed by the likes of Peter Gabriel and the folklorist Hamish Henderson who labelled it 'brave new music'. This biography traces his story through personal struggles and artistic triumphs, and offers an assessment of his place in the pantheon of major Scottish artists. It is a story of resilience as well as innovation: twice diagnosed with unrelated cancers, his professional career lasted little more than a decade, and he fought serious illness for half of it. He died in January 2005, aged 33. Yet his art continues to inspire: where he led, others have followed, and his music still wins awards and fills concert halls at major international festivals two decades after his death.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 457

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

GARY WEST is a writer, musician and broadcaster based in Edinburgh, who has spent his professional life researching, teaching, performing and promoting the cultural and musical traditions of Scotland. A former professor and head of Celtic and Scottish Studies at the University of Edinburgh, he has published widely on the themes of music, heritage and folklore. He presented the specialist music programme Pipeline on BBC Radio Scotland for two decades before developing his own podcast, Enjoy Your Piping, which promotes bagpipe music on a weekly basis to over 100 nations worldwide. He serves as an external examiner at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland and the University of the Highlands and Islands, and in 2020 was inducted into the Scottish Traditional Music Hall of Fame.

First published 2025

ISBN: 978-1-80425-212-3 hardback

ISBN: 978-1-80425-211-6 paperback

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

Typeset in 11.5 point Sabon by Main Point Books, Edinburgh.

© The Martyn Bennett Trust 2025

Contents

Overture

1 Beginnings

2 The Music Apprentice

3 Making a Name

4 First Born

5 Bellows Boy

6 Bothy Culture

7 Cuillin

8 Home

9 Glen Lyon

10 Grit

11 Blessed Warrior

12 Passing On

13 Liberation

Timeline

Author Acknowledgements

The Martyn Bennett Trust Acknowledgements

Photo Credits

Endnotes

Note to Martyn from Hamish Henderson.

Grit Orchestra, Playhouse, Edinburgh.

Overture

IT WAS THE most remarkable of standing ovations. All 3,000 of us sprung to our feet as a single, stamping mass. For the last two hours and more we had been immersed in music. Bold, brave, ballsy music. The man at the centre of things, baton in hand, all in black, was the epitome of cool. Facing him and us were around 80 of the Scottish nation’s finest musicians, their usual labels of ‘folk’, ‘jazz’ or ‘classical’ cast aside in tribute to the eclectic soul of the music they had come to play: the music of Martyn Bennett.

In the summer of 2016 Greg Lawson had brought his Grit Orchestra to the Edinburgh International Festival. He had spent many months painstakingly reconstructing Martyn’s final album, the one from which the orchestra had taken its name. Some 13 years earlier, Grit had been crafted almost entirely on a computer, for the cancer gradually taking hold in Martyn had also been disconnecting him from playing his beloved instruments. In fact, these instruments were no more – he had smashed them into pieces in a fit of frustrated, pain-induced rage. His bagpipes had made it through two world wars, he lamented, ‘but they didn’t make it through my war’.

What he did still have though was a deep love of the great voices of Scotland’s past that had carried with them that vibrant, earthy song tradition into which he had been born and raised. And what’s more, as he was always keen to point out, they were the voices of people he actually knew. Under them, over them, through them, all around them, he had draped a soundscape that drew on his long, intensive years of training as a piper, flute player, pianist, classical violinist, DJ, programmer, composer, producer, mountaineer and darling of the club dance floor. It was all in there: a love letter to the past, a celebration of the multi-cultural present, a glimpse, perhaps, of the future.

Grit, Martyn Bennett’s fifth album, had been released in October 2003 to much acclaim. Tragically, he died 15 months later, on 30 January 2005. And so as we took to our feet in the Playhouse that evening, yes, we were acknowledging Greg Lawson’s incredible achievement in reconstructing for the stage a musical creation that had only ever existed in a machine. And yes, we were cheering the 80 or so musicians whose skill had brought that score to life. Yet above all, I think, we were saluting the man who was no longer there in person, but whose presence and spirit I fancy we could all feel intensely that night.

The special atmosphere that was created by the Grit Orchestra mirrored Martyn Bennett’s own live performances which could also be epic events. He knew how to put on a show for sure. They were often transformational for those who were there, creating indelible memories and a loyal fan base, as his wife Kirsten commented:

There is so much written and remembered by folk whose lives were literally affected by the energy of these gigs whether they were early solo gigs or band gigs – it was Martyn who created that energy and whipped crowds of people into frenzied audiences all over the world. So many people would say that they came along to the gig because they couldn’t understand the description of the music and they were intrigued. These people became really dedicated fans – it all made sense when you heard his music live.1

In the years since he died, Martyn’s ability to inspire has shown no signs of diminishing: his music has filled concert halls and arenas, his story has been shared on the theatre stage, much of his other work also recast in full orchestral form, his memory toasted, and his name cited as their key inspiration by many young musicians who have followed in his wake. Martyn Bennett was a game-changer, but he never got the chance to write his own story, or not in book form at least, and I suspect he was not the kind of man who would ever have even contemplated doing so. His music did the talking. And so while researching and writing this book, I have continually wondered what he would make of the fact that someone is attempting to do it for him. He can’t ‘authorise’ it, nor indeed can he specifically unauthorise it. I have imagined how he might react to my words in different places – shake his head in disbelief, roll his eyes at my pompous pontificating, throw his head back in laughter, or simply get bored of reading about himself and take to the hills instead.

The last time I ever saw Martyn he was chatting to someone at a CD launch, and introduced me as being the ‘slightly academic guy who presents the piping on the radio’. I remember the phrase precisely, not because I knew it would be the last I’d ever hear from him (of course I didn’t) but because I was tickled by the ‘slightly’ qualifier. I mention this simply to point out that it may also be an accurate description of this book. It is slightly academic in that I have set out to assess Martyn’s place in his world, to offer as balanced a view as I can of his contribution to the culture of his time, and to build some layers of context relating to what went before him and what he in turn has passed on. In the pages that follow I paint a picture of Martyn Bennett that draws on all of the varying versions of him shared with me by those who knew him best. Martyn lived in a world of sound, a good deal of which he created himself. However, my task here is to represent his extraordinary life in a world of words on the page. That has been tricky, for writing about music, as they say, is rather like dancing about architecture! So read on, but please do go and listen to his music for yourselves too. You will be marvellously rewarded, I assure you!

Gary West

Edinburgh,

November 2024

1

Beginnings

IT WAS A potent combination of geology and folklore that made Martyn Bennett. He was born in St John’s, Newfoundland, Canada, on 17 February 1971, his parents, Ian Knight and Margaret Bennett, having met after each travelling to Memorial University to further their academic studies. As a promising young geologist, Ian was keen to explore the rock foundations of the west of the island, while as a folklorist, Margaret immersed herself in the cultural traditions that had evolved on its soils. Both were destined for successful careers in their respective fields, each gaining awards as well as wide recognition and professional respect from their peers. Later in life, Martyn reflected on his roots there:

I don’t know if anyone knows where Newfoundland is! Well, the reason I was born in Newfoundland is simple, because my mother, Margaret Bennett, is a fairly well-known folklorist nowadays and the reason for that is because she went there as a teenager to do a Master’s degree with quite a famous folklorist called Herbert Halpert. She went to Newfoundland to study with him but at the same time she found a community in the west coast. A place called Codroy Valley where people were still speaking and singing songs in Gaelic and playing fiddle tunes and pipes and things and a lot of the stuff they were doing had sort of died out in Scotland – well not so much died out, it was like it had been preserved but in Newfoundland it hadn’t been preserved in a pickling jar. It was actually part of everyday life and so that’s how she ended up there.1 And then she met my father who is Welsh and he was a fiddle player. And I transpired from that!2

The fact that Margaret’s own father had moved to Newfoundland some years before had created an initial close connection there for her, but a further pull was the chance to study under one of the most revered folklorists in the Western world, Herbert Halpert (1911–2000). Her own immediate roots were in Skye, where her mother’s people, Stewarts, had lived for many generations, and where Margaret and her three sisters spent their formative years. With a singing mother and piping father, music, song and story were a constant presence in the family home on Skye, while spells on the Isle of Lewis and in Shetland served only to broaden her cultural awareness and to heighten her sensitivity to the nuances of localised tradition.3

Margaret’s research in Newfoundland took her to the Codroy Valley, a fertile estuary between the Anguille and Long Range mountains on the south-western tip of the island, a rich hunting ground for a youthful Highland folklorist. Settled by Micmac, French, English, Irish and Scots, the rich cultural layering to be found there was always likely to be a magnet for her, but the fact that the Scots included several families of Gaels proved to be an irresistible draw. As she was later to explain in her book, The Last Stronghold, these were mainly secondary migrants who had made the journey across from Cape Breton in the mid-19th century, and who still retained a strong oral tradition, carried by the Gaelic language, that connected them directly back to the west Highlands of Scotland that Margaret knew so well. Martyn was to come to spend a good deal of time in his early years amongst these folk, retaining a lifelong fondness for them and a sense that he had been given an unusual outlook on the world by this start and a feeling of being an outsider:

I still love to go over to Codroy Valley. I haven’t been for quite a few years, but the people there are very interesting. They’re from Moidart and Appin and they’re French, French Canadian as well and they’ve been married into these big families, Cormies and MacArthurs and MacIsaacs, they’ve all intermarried and so they have a very strange view. My early childhood’s a strange view of the world you know? So I started from a strange place.4

When Margaret made her fieldwork visits to the homes of these people she had ‘a very young research assistant’ who would crawl under tables to find sockets for the recording machine and regularly add in some questions of his own to the research encounter:

I’d always give him a role in the collecting trips, carrying a microphone stand, keeping an eye on the tape to make sure it didn’t run out. During the recording session he listened intently, and I didn’t realise until years later what a remarkably retentive memory he had. Not just for tunes, but for words too, and he remembered complete stories – some emerged years later on his albums. What goes into small minds?5

One thing that must have gone into Martyn’s mind for sure was an appreciation that ‘ordinary’ people could have extraordinary stories to tell, and that they themselves are the best placed folk to tell them. Allowing them to do so is what folklorists are all about, and Martyn was to witness many such collecting sessions throughout his childhood years. They had a significant influence on his thinking, his outlook and eventually, his work, and it seems to me that Martyn was to spend most of his life wrestling with that slippery concept which motivated so much of his mother’s collecting: tradition. His relationship with it was intense and complex, yet it sits at the heart of so much of his creative output.

From early infancy Martyn was immersed in traditional music and culture simply by accompanying his mother. Her memories of these encounters and experiences also strongly suggest that Martyn was a remarkably curious and sensitive wee boy, especially when it came to understanding and experimenting with making sound. In a talk to students in the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland in 2023, she recounted an extraordinary occasion where she had confiscated the remote control from a toy car from Martyn, who was about five years old at the time, and had been told to stop driving it but had disobeyed. Margaret later discovered Martyn in the kitchen with a pair of spoons. It transpired that he was hitting them together in hopes that the soundwaves might move the car! This early fascination with the technicalities of sound was evident, as his mother remembered, on another occasion, when Martyn climbed onto the knee of an Inuit throat singer at a folk festival in Mariposa, Ontario, and asked to see into her mouth in an attempt to work out how she made such an amazing sound!6

Ian Knight was also drawn to the west coast of Newfoundland, but in his case it was the land itself that fascinated him rather than the ways of life that had developed upon it. From Cardiff in Wales, Ian initially moved to Newfoundland to undertake a graduate degree studying rocks in remote areas of Labrador. He later undertook research for the Newfoundland Geological Survey on the west of the island, including in the Codroy Valley and the neighbouring Anguille Mountains. Ian’s research on the island was a key step in his development as a leading light of Canadian geology, as someone who, in the words of a colleague, ‘reads rocks like a book, with a sharp eye for the smallest detail’.7

Ian and Margaret married in the spring of 1970, but went their separate ways in 1976, Margaret and Martyn moving briefly to Quebec and then on to Scotland. ‘Looking back, I cannot help but see my role in his life as minor, as the time spent together after his mother and I split can be rolled up into not more than a year,’ Ian reflected.8 Living an ocean apart, of course, makes any relationship difficult and the combination of distance and circumstance led him to follow what he describes as a ‘staccato life’ with Martyn, and a relationship that was necessarily shaped by a different ethos. ‘Although it is not widely known’, he pointed out, ‘we shared the same birthday yet were rarely – if ever – together on that day during his early years’. A mid-February birthday does not coincide with lengthy Scottish school holidays and it was only really in the summer and some Easter and Christmas breaks that Martyn was able to spend prolonged periods with his dad. At times they met up in Wales to stay with Ian’s parents, heading out to the Brecon Beacons to climb Pen-y-Fan, or to the Gower Peninsula for cliff top walks. His Welsh grandparents loved him, but rarely saw him, and as Ian acknowledged, they were not closely involved in his life beyond the sending of a card or present at Christmas and on birthdays. When Martyn did visit, rugby matches at Cardiff Arms Park in his teen years were high on the agenda, at least for his grandfather who was an avid fan. On one of his trips to Wales in his early teens Martyn played his pipes on the front lawn of his grandparents’ house dressed up in Highland gear, a sight and sound that the neighbours remembered for many years after.

In the early years following his separation from Margaret, Ian was heavily involved with a Wesleyan church in Mount Pearl, a town adjoining St John’s in Newfoundland. The Church of the Nazarene took an evangelical approach to its teaching and practice, a legacy of the Holiness movement in the USA, and the much earlier teachings of John and Charles Wesley in Britain, and Martyn went with his dad to some of the camps they ran. Reflecting on that time now, Ian speaks perhaps with a hint of regret: ‘I suspect that it was not that beneficial to either of us and it was only after my loss of belief in the early 1980s that we were able to enjoy visits as he grew older’. By his mid-teens, Martyn’s trips to Newfoundland grew longer, and together father and son would head out on adventures west and north during Ian’s summer geological fieldwork. Camping in the woods, they explored the coast of west Newfoundland bays and islands in zodiac and fishing boats, worked in canoes on lakes, flew in a helicopter and searched for rocks and fossils. While Martyn relished the adventure, Ian suspects that ‘trailing around with a dad who is measuring strike and dip of rocks and rhapsodising lyrical about faults and sedimentary rocks was likely boring on many occasions’, and Martyn was never beyond a bit of a lark should he spot the chance to have some fun. ‘He found a grey, putty-like glacial mud in a karst hollow on a limestone island in Hare Bay, Great Northern Peninsula, when we were there on a bit of a dreary day and it wasn’t too long before we were enjoying lobbing fists of sticky pudding at each other and smearing mud on our faces’. Yet boating close to whales and seals, glimpsing eider duck and tern colonies on rocky islands, and finding curious families of red fox cubs poking heads out of their many den burrows in an abandoned saw mill’s slab and sawdust pile, were all part of the field work thrills. Encounters with beaver, otter, moose and caribou were by no means unknown either on these trips.

The mountain of Gros Morne in the National Park in western Newfoundland was a favourite for father and son to climb together or along with Ian’s partner, Ruth, as Ian recalled:

Rather than follow the marked route we most often went straight up the steepest slope to the bare summit and then found a moose trail to get lost on coming down the wooded back of the mountain. Other climbs over the Gros Morne Tablelands, vast orange and yellow coloured ophiolitic slabs of ancient ocean floor saw us chased off the grass-tussocked mountain plateau by high winds driving low clouds and rain squalls that you could see coming from afar.

Martyn also had a remarkable head for heights and was able (and willing) to jump onto a grassy pedestal overlooking a sheer drop of a thousand feet ‘without fear’ as he did above the St Mary’s bird sanctuary on the Avalon Peninsula. Ian still shudders when thinking about that! ‘He’d climb rock faces without a second thought and would be with me one minute and waving from a cliff face the next. And don’t give him an ATV (all-terrain vehicle) on a gravelled woods road: he was a wild demon, gone before I got my helmet on and could chase him!’

Despite Ian’s suspicion that Martyn may have found the fieldtrip outings at times boring, the training seems to have stayed with him. When discussing his process of composing his final album, Grit, in 2003, it was a geological analogy that came to mind for Martyn. Instruments and electronics, he announced,

are just tools for something I already can hear. It’s like I can hear it and sometimes it’s quite hard to actually get it out. You find sometimes it’s like a bit of unhewn stone, you know. Sometimes the stone is kind of softer, it’s limestone or soap stone even. It really just happens quick. It’s done, you know. In a day or so you’ve got this track that you heard in your head that morning. But sometimes it can be a bit of granite, can’t it? It can be hard, a bit of hard rock and you do it for ages and you just can’t seem to get it.9

There was plenty of music in Martyn’s life from the outset. In the early years in Mount Pearl before his parents separated, records of the Wombles, Peter and the Wolf, Gaelic singing, Cape Breton fiddlers, and a few classical albums such as Pictures at an Exhibition, and Mozart’s Horn Concertos were played on the little stereo system. And for Martyn, it wasn’t just a case of listening, but often the stories behind the music had to be acted out too. ‘There was an element of theatre to it all,’ recalled Margaret, who in Peter and the Wolf invariably had to play the part of a bassoon!10 Martyn liked to be sung to by both his mum and dad – songs of the Beatles, Bob Dylan and Judy Collins as well as a few popular Welsh songs and hymns are the ones that stick in his father’s mind. Ian had played violin in the Cardiff Schools Orchestra and tried to learn to play fiddle when he moved to Newfoundland as a graduate student in the early 1970s. Memorial University geology department was almost an amateur folk music school with both staff and graduate students who played instruments, as Ian reflected:

I played the violin but not that well and I couldn’t play fiddle tunes for the life of me, as hard as I tried. To play popular and Scottish fiddle tunes by ear, it took me many years and I only got to play reasonably with the help of a tape of Aly Bain and the many Cape Breton fiddle records available at that time. It was a hard slog to change styles and play by ear, but eventually I got one tune and then others followed – but it was never fluent. Some of us grad students formed a small group called the CFA band, which stood for ‘Come From Away’– a Newfoundland term for someone not born on the island. We played our gradually expanding repertoire of tunes at parties and winter carnival, meeting sometimes at our house. Margaret was to bring me into contact with Scottish Gaelic singing and fiddle playing which I loved.

One Irish tune that was popular in St John’s and that was a favourite of Ian and his band mates was the ‘Swallowtail Reel’. Martyn was familiar with the tune from the playing of the band, Ryan’s Fancy, and it was also later to be a favourite of his when jamming with Edinburgh-based flute player, Cathal McConnell, but it is also a tune that has a lasting poignancy for Ian:

We were belting it out at a university winter carnival concert and were in full swing as were the rowdy students when my mind went blank. Luckily it was in a key that meant I could play two open strings imitating a pipe drone so kept fake fiddling until the tune came back. The students didn’t seem to know or care as they kept clapping along and dancing their jig. It was a fellow geologist friend from the band, now living in North Carolina, that many years later pointed out after I sent him the CD after Martyn died that this opening tune on Martyn’s first album was once a favourite tune of the band – I like to think that perhaps it was a quiet nod to the story and me that he opened the album with that tune.

Martyn was four years old when his parents went their separate ways, Margaret moving with her son to Quebec for a short stay to carry out more fieldwork amongst communities of Gaelic speakers there, and then on to Scotland where they eventually settled in Kingussie, while Ian remained in Newfoundland. While both live and recorded music in the house certainly formed a soundtrack to Martyn’s early life, for Ian there was no hint that his son was any more musical than any other kids, and certainly there was no indication for him that it would be music that would shape his future. This is not a casual aside from Ian, but rather a strong and insistent conviction: ‘I suppose my greatest fear’, he explained, ‘is that there will thrive a mythology about him that would be unfair to his memory and would make him unhappy’. The heart of the issue, in Ian’s view, is that Martyn, like Mozart, was a child prodigy who was always destined for musical greatness. He saw no signs of this at all, in his recollection, and while their time spent together was limited, he felt sure that any deep interest or talent would surely have shown itself in their weeks together:

If the relationship is good between a dad and his son, and I believe ours was, and you meet for only a short time during holidays, then an excited child wants to show you things that he knows and does – Martyn did none of this in musical terms and just enjoyed tussling on the rug, building models, fishing and other things that we did. There was a piano at my parents’ house, sometimes I had my fiddle with me and sang and played at church and church camps including playing at a barn dance in the communal dining room of an old, majestic, monastic, English friary building, now a private school. Martyn had no interaction with the instruments and not a particularly favourable response to the dance even though it was a pretty wild and happy time.11

For Ian this is important, not only for our understanding of Martyn, but because ‘the sudden blossoming of his talent almost out of the blue’ brings hope for children everywhere who do not seem to have much interest or direction. ‘I hesitate to push my own ideas’, his father explained, ‘but I think that the musical evolution of Martyn reflects the talents and brain of a young, maturing, very talented, musically intelligent person rather than speculating on possible mysteries of an infant prodigy. It goes without saying that he benefited immensely from the advantages and encouragement of Margaret’s guidance and immersion in the traditional music in Scotland with all the great players, singers and poets that he was able to hear and later honour in his music’.

Yet the music he was hearing in early childhood certainly stayed with Martyn all his days. In one of the interviews he gave late in his life as part of the making of a BBC Scotland Grit documentary, that was made very clear:

The first song I ever remember would have to be ‘Train on the Island’. Is that a Woody Guthrie song? Not sure if it is or not?12 ‘Train on the Island, hear the whistle blow, gone to visit my true love, I’m sick and I can’t go’, so that was the first song I ever learned was about being sick so that kind of sums up my life really! (laughs). Second song I remember – a song about a mother asking her son what he’d been eating in the woods.13 He said ‘snakes mother’. ‘What colour were the snakes’? ‘Green and yeller’ (laughs). ‘Mother be quick, I’m gonna be sick and lay me down to die’ (laughs). They are all happy songs. When you are a kid every song is happy. And I loved eh, Peter and the Wolf. That was my favourite. Peter and the Wolf, Prokofiev. I think I’ve got one with – not sure if it is Alistair Cooke or if it was one with Sean Connery.14 It might have been Sean’s one. (In a Sean Connery accent) ‘Peter said to the wolf’. And his grandfather. I loved the grandfather tune (sings). Do you remember that one? It was great. The grandfather theme. (Sings again), that’s Peter isn’t it? I liked that one. Got it somewhere actually, Peter and the Wolf on vinyl. I have to do something with it. Yeah (sings). Mr Scruff version of Peter and the Wolf. Could be done! (laughs).15

Although Ian rejects the ‘child prodigy’ idea, once Martyn began to develop his piping, his father was indeed astounded at the rate of his progress. The first time he heard him play was soon after he had started lessons in Kingussie, and the two of them were on a train together, alone in one of the old-fashioned compartments. Exactly where this was Ian cannot recall, although he believes it may well have been in the area of the Welsh marches of Longmynd, travelling to South Wales to visit Martyn’s grandparents. ‘He pulled out a piping book and a chanter I believe his grandfather Bennett gave him, and just began to play – looking at the sheet music it was as dense in black notation as a spruce wood plantation in Scotland or new growth forest in Newfoundland, and incomprehensible to me’. Ian also marvelled at Martyn’s sense of pitch and rhythm and that he could also commit the tunes in his head to paper with great ease. ‘On one trip to the Cairngorms to ski, we were discussing tunes and without any hesitation he swiped out a pen and pad, drew some staves, and proceeded to notate a tune for me – such gifts I wish I had’.

Kingussie

On moving to Scotland in 1976, Margaret and Martyn spent a short while in Mull where Margaret performed tourist concerts in a local hotel before securing a job as a teacher. This took them to Dumfries which at the time had one of the most active folk clubs in Scotland, and they quickly became part of the ‘folk family’ with the likes of Billy Henderson, Phyllis and Billy Martin and Lionel McClelland all adding to Martyn’s passive repertoire. After two years a supply-teaching job took them to Glasgow, where Margaret re-married. The folk scene there was a big part of their lives, as her husband, Joe McAtamney, loved to sing and other ‘folkies’ often gathered at their house. In 1979, the three of them settled in the town of Kingussie in Badenoch, some 40 miles south of Inverness. ‘The small town with a big heart’, it brands itself nowadays, and for a wiry young lad with an acute sense of adventure and a liking for the hills, it provided a fine playground indeed. These were key formative years for Martyn: it was here he underwent a good part of his schooling and here that he learned to play the bagpipes, making his first public performances as a musician. It was from here that he ventured out with his mother to folk festivals across Scotland where he peered into the deep well of tradition, and here, too, that he began to develop a sense that he was just a little bit ‘different’. Martyn later reflected that he felt something of a ‘social misfit’ at school there, his small stature now very noticeable next to the hulking shinty-playing locals who seemed to dominate his new school environment:

I hear people say that they felt like they were a bit of the odd ball at school you know. In Kingussie High School I was the smallest in the whole school and kind of lived in amongst strong, strapping farmer lads! I had to get tough and I found when I later went to the city I was the toughest and I was the most motivated.16

His memory of this discrepancy in size is corroborated by accounts from adults who encountered this unusual wee boy for the first time. David Taylor, his main piping teacher, recalled him being ‘very tiny’, while storyteller Dolly Wallace remembering Highland Nights in the Grampian Hotel in Dalwhinnie where Martyn would pipe for a six-year-old dancer, remarked: ‘And they must have been the most photographed pair in Britain at the time, because they were so small, so neat, and so sweet and pleasant. It was just flashing lights round them! Oh the tourists loved it!’17 In Martyn’s own later recollection, in learning to play the pipes, he went from feeling diminutive and unremarkable to having a special talent that got him a great deal of attention:

By the age of 12 I was winning prizes in many of the junior piping competitions around Scotland, however I was really more interested in playing the folk scene. Being a young prodigy meant that I got a lot of attention at the folk festivals, as there were very few young musicians around at that time. It was also a total gas being snuck into the pubs under someone’s coat and getting the pipes out before anyone had noticed the under-age drinker. By the time I’d got through the first tune and the place was jumping they were hardly going to chuck me out, were they?18

Piping was in the family, and the first set of bagpipes Martyn ever heard was played by his grandfather, Margaret’s father, George Bennett. It was ‘Papi’ who gave his grandson his first practice chanter, and the two of them would discuss the merits of certain tunes, playing styles, and the etiquette of kilt wearing (no red shoes!). Margaret would later donate her father’s pipes to be used by the students of the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, Martyn’s alma mater, a gesture to the influence George had on the path his grandson was to take in music. That said, that relationship wasn’t always totally harmonious, as Margaret recalled with amusement:

My mother and father spent a lot of time with us when Martyn was growing up, and my father – who gave Martyn his first chanter – could be bit a Victorian about manners. We were sitting down to dinner one day; I’d called Martyn, who was about 14, and he came bounding into the room and plonked himself down in a chair – just exuberant, like he was. But my father was not impressed at all, and said to him, ‘Young man, would you mind leaving this room, then returning and sitting down like a gentleman.’ So Martyn just seemed to take it, went away and came back and sat down quietly; there was a bit of a silence as we all just carried on eating, and then Martyn piped up: ‘Papi, do you know what I’ve just been thinking?’ ‘No, Martyn, what’s that?’ ‘Sometimes I think you’re a bit of an old bastard.’ I nearly died: dropped my fork, almost choked on my food, but then I could tell my father was stifling laughter, even as he tried to be stern: was I going to allow my son to talk to him like that? So I spluttered something about how I’d certainly never encourage such behaviour and then found myself saying, ‘But I have thought the same thing myself, sometimes!’ Ever after that, whenever Dad phoned, once he and I had spoken he’d say, ‘Where’s my grandson? Tell him it’s the old bastard on the phone.’ Even I’d been a bit scared of him before, but Martyn saw beyond the strictness – and completely disarmed it.19

While it was George who first stimulated Martyn’s interest in piping, it was one of his teachers at school in Kingussie who nurtured it and set him on his path to greatness. In an interview given to publicise Grit in late 2003, Martyn confided to Ann Donald of Scotland on Sunday: ‘I was really below average academically for a lot of my life and it wasn’t really till I knew this amazing teacher, David Taylor, who taught me piping, that I felt here was something I could do really well.’20 David Taylor became the single most important influence in the discovery and development of this young man. A history teacher in Kingussie High School, he has a strong piping pedigree himself having been taught by Bert Barron in St Andrews, a hugely influential and slightly eccentric character who could count among his piping pupils several future gold medallists and major pipe band leaders. Bert was also a dab hand at procuring, refurbishing and selling on high-quality sets of old bagpipes, and it was from him that David secured Martyn’s first ever set. They were full ivory-mounted Henderson’s, often considered the ‘Stradivarius’ equivalent of their kind. They cost the equivalent of a month’s teaching salary, recalled Margaret, who paid for them by taking in Bed and Breakfast guests. Martyn was later to inherit an even older set from his grandfather Bennett, but according to David, he took to that first set as if they were just made for him. That said, he had to grow into them: for the first couple of years he couldn’t reach the tuning slide on the bass drone over his shoulder, so he came up with a unique method of turning the pipes upside down to tune them! As his mother remembered, ‘he used to wonder why some folk laughed even before he started to play!’

The respect that Martyn held for his main piping teacher was certainly mutual. In his contribution to Margaret’s collection, It’s Not the Time You Have, David’s admiration and pride in his star pupil was obvious:

I first remember Martyn as a very tiny, excited, desperately enthusiastic wee boy with wide shining eyes. I’ve never seen anyone learn the chanter so fast. In his first lesson (1980) he mastered everything I gave him first time round – I probably gave him a month’s worth of lessons in our first meeting. He was the most natural learner I’ve ever encountered – even making a practice chanter musical and playing grace note scales with perfect rhythm. It was only a few weeks before he was playing his first competition tunes on chanter. He had such light musical fingers when he played and even the hardest tunes flowed in such a natural, musical way. His impish sense of humour combined with his amazing talent meant he was always tremendous fun to teach. I looked forward to our lessons as much as he did.21

Martyn also took some piping lessons from John MacDougall, one of the leading competing pipers of his generation who lived locally, and who was employed as a piping teacher in the Badenoch and Strathspey schools. In the 1970s his fellow competitors began to call John ‘The Highland Hoover’, as he dominated the Highland games circuit, sucking up all the prizes! He reputedly used to practise in a nearby disused quarry, in all weathers, to prepare himself for the unpredictable conditions of the outdoor competition circuit. Perhaps some of that meticulous attention to detail rubbed off on his young pupil who was certainly in expert hands there, but Martyn did make the point on several occasions that he considered David Taylor to be his key musical influence: he was unequivocal on that. And others who benefitted from David’s teaching in the school – whether history or music – also concur with Martyn’s view. Pianist and composer Mhairi Hall, one of today’s leading Scottish traditional musicians, attended the school some years after Martyn:

Retired history teacher David Taylor was one of my most inspirational teachers at Kingussie High School. He really brought the subject to life and got very animated in class, especially regarding Scottish and Highland history. He used to run two-week long school trips up to Orkney over the Easter holidays so that every child spent time on the islands there, living the history and feeling connected to both our past and present. He taught many pupils piping, including Martyn. Rather than a pipe band, he ran the school folk group and that was where I started playing traditional music. He taught us the best traditional Scottish repertoire, that has stayed with me throughout my musical life. He regularly spoke about Martyn pushing the boundaries of our music and once suggested I go to a concert he was playing up at the Daylodge of Cairngorm Mountain. That was my first live concert seeing and hearing ‘Cuillin Music’, having listened to his first album and Bothy Culture until they were worn out. He gave me a letter to give to Martyn. I don’t know what was in the letter but Martyn spoke to me as if we had been in school together, learning at the same time. We had a connection and shared experience being taught by this incredible teacher. (I was a bit of a starstruck teenager!) On reflection, David gave us an understanding and connection to our history, our present and how these veins run through our music. This of course is so abundant in Martyn’s music, and I’m sure some of David’s teaching must have rubbed off – it certainly has with me.22

David himself can recall in detail one of these field trips to Orkney that Martyn attended in his first year at the high school.23 ‘For all his sense of fun and mischief he was actually a very serious young lad in many ways, and he was determined to get everything he could out of the trip’. He remembered Martyn lying on the wall of one of the houses at the Neolithic settlement of Skara Brae, ‘sketching it in incredible detail and wouldn’t leave until it was right’. Martyn was indeed a talented visual artist, and at that stage it was art rather than music that excited him most, and it did seem likely for a while that this would be the path he would follow. ‘It was a brilliant sketch for a boy of just 12’, David concluded. When the art teacher saw it he dismissed it as having been copied or traced from a book. ‘But no’, remarked David, ‘I watched him drawing it with hands numb from the bitter Atlantic breeze that sweeps over Skara Brae’.

As with so many recollections concerning Martyn, humour is never far away, and David continued with a classic of his own:

Another story from there that illustrates the impish sense of humour. I was commenting to the kids how much I’d like to get down into the one of the houses to get the real feel of it. So Martyn ‘accidentally’ dropped his clipboard into the house, and said with a twinkle, ‘Mr Taylor, I’ve dropped my worksheets – could you possibly go in and get them for me?’ I was just about to seize my opportunity when the old Custodian said, ‘Don’t you worry boy, I’ll just go in and get it for you’. Martyn just laughed so much at how his ruse had failed! Years later I got a postcard from Orkney from Martyn, who was playing at the folk festival there. I still have it. He not only remembered, but took the time to write. That was Martyn.

Alongside his art, Martyn soon became obsessed with piping; according to his grandmother Peigi, a frequent visitor to Kingussie, ‘he used to read the Kilberry Book of Pibroch in bed, he’d write music in bed.’24 He began to compete in mods and other competitions, with a good deal of success, although he was very clear to his teacher that the rigid formalities of that kind of playing was of little interest to him. ‘He found it restrictive and felt unable to express himself the way he wanted to. He wanted to play folk style – the rhythms of Aly Bain and Cathal McConnell rather than the more stilted reels of competition style’. He may not have enjoyed the established competition repertoire, but he could certainly play it, and play it very well. Margaret has a recording of her son playing a strathspey and reel on his pipes aged 12, and having heard it I can say with confidence that he was indeed exceptional. The tunes were of the complex, heavy form – ‘The Shepherd’s Crook’ and ‘Pretty Marion’ if I remember correctly – and he played them with both technical precision and great musical lift. It was a remarkable performance for a boy of that age. There is also a recording of him singing a Gaelic duet with a young local girl, Lucy Anderson. Lucy carries the melody, while Martyn provides the harmony. To extemporise a harmony was something Martyn found easy, and I twice experienced this directly when he was in his teens and he played his pipes along with me, going for harmony all the way. I didn’t know what tune I was going to play next, so there’s no way he did either!

As well as formal instruction on the bagpipe, Martyn was able to soak up the styles and nuances of traditional music more generally on his visits to folk festivals and gatherings with his mother, a regular feature of his time in Kingussie. In the early years of the folk revival in the 1950s and ’60s, a handful of singers had gained recognition as ‘the real thing’. These were people for whom the singing of traditional songs and ballads had always been part of their lives, but the flowering of wider interest in folk culture had brought them newly found recognition and they were now being placed – quite literally – centre stage. They became labelled as ‘tradition bearers’ and ‘source singers’, and Martyn got to know them all. Many were of the travelling community – Duncan Williamson, Belle Stewart and her daughter, Sheila, Willie MacPhee, Betsy Whyte, Jane Turriff, Elizabeth Stewart and Lizzie Higgins were all singers and storytellers whose faces and voices were familiar to Martyn, while he got to know nontravellers such as Jock Duncan and Flora MacNeil also. Margaret remembers when her son first came across Jane Turriff, a traveller singer from Fetterangus in Aberdeenshire:

We were at Auchtermuchty festival and he’d gone off by himself while I was recording a competition. He came running along the street to find me. ‘Come and listen to this’, he said, ‘you’ve never heard the likes of this old lady yodelling and everything!’

Martyn drank in everything these artists sang, and they noticed him too: as Sheila Stewart remarked, ‘they were glad a young person was interested’. That interest would never leave him, and he was later to draw on it directly in his final album, Grit. Reflecting on that following its release late in his life, he explained in an interview with the broadcaster, Mary Ann Kennedy, just how important those early experiences had been to him:

These are voices I knew as a child – these are people that I knew when I was starting to play music. At TMSA festivals I would hear them, and they were the celebrities if you like. No Posh and Becks for me then! It was the likes of Lizzie Higgins who were my kind of heroes. I got to hear them at the likes of Kirriemuir, Keith and Auchtermuchty. I haven’t been to these festivals for so many years… I didn’t know what a privilege it was for someone of my age – but then no one my age was interested. And I wasn’t forced into it – it wasn’t like Margaret Bennett said, ‘Right boy, you’re going to become some sort of folklorist and pass on this tradition!’ I was just brought up around it.25

The important formative years in Kingussie drew to a close when Martyn reached his mid-teens and life took a new turn when Margaret accepted a lecturing job at the School of Scottish Studies at the University of Edinburgh. It was time for the young lad to get his first real taste of city living, and although he could not have known it then, it was a move that set him on a journey that was also to define the rest of his life.

2

The Music Apprentice

Broughton

AT THE AGE of 14, Martyn Bennett travelled to Broughton High School in Edinburgh, pipe box in hand, to audition for the specialist music school there. Founded in 1899 as the main ‘higher grade’ school in the north of the city, Broughton had its share of notable alumni. One who made a major contribution to Scotland’s creative culture was a certain Christopher Murray Grieve, who attended for a few years in his teens before later emerging as one of the nation’s greatest modernist poets under his assumed name of Hugh MacDiarmid. (That said, his stay at Broughton had been relatively brief, having been expelled for stealing books!)

The specialist music unit was a much later addition, having been set up in 1980, aimed primarily at ‘classical’ players and so when this young piper and whistle player walked through the door with hopes of securing a place, it was new territory for the staff. Margaret had taken advice on Edinburgh schools from some of her new colleagues at the university, and had gathered a variety of school prospectuses.

Martyn had been very taken with the idea of going to Broughton when he read about the set-up there that was specifically for ‘musically gifted children’. This came as something of a surprise to his mother, as up to that point he had shown little interest in playing music beyond his piping, and an earlier attempt to take up the violin had been short-lived. At the age of seven he had taken lessons but one day refused to go back to school after the summer break if he had to carry on with them. It was many years later that his mother discovered why – the teacher was something of an eccentric old maid who had been so taken with his early progress that she scooped him up and planted him with a kiss in front of the whole class. The fact, as he later divulged, that ‘she had whiskers’ had cemented his decision! And while Martyn was also no total stranger to the piano, his formal lessons before his Broughton days were very limited. From a very young age he would play away on his own, happily exploring the sound and mechanics of the keyboard, an approach that his mother was advised to encourage until beginning a brief run of lessons in Glasgow at the age of ten. Their move north to Kingussie put a stop to those, however, and no more piano lessons followed until his arrival at Broughton.

Mary McGookin was a principal teacher there at the time Martyn arrived, and remembered eavesdropping on his first audition:

I wasn’t on the audition panel at the time but I was in the school and I heard piping and it was unusual to hear piping because at that point I think we had a range of instruments but no traditional instruments. And I could hear it coming from one of our classrooms so I went to have a look and then I realised it was a kind of pre-audition. We normally have two stages of auditioning so this was the more informal one but I could hear this piping and I could hear that it was really, really good. And I was lurking outside the door and listening and hoping that we could take that leap and admit someone who was not on the kind of normal classical route.1

Margaret was also waiting on her son outside the door and recalled ‘a gale of laughter’ spilling out of the classroom. ‘It was embarrassing,’ she laughed:

They had asked him if he could play anything else, besides the pipes. ‘Yes, the tin whistle.’ ‘What can you play?’ He told them he would play ‘The Arrival of the Queen of Sheba in Galway,’ and promptly played a flashy tune he heard on the hit-parade. It was from James Galway’s The Man with the Golden Flute record. The playing was note-perfect, but the title made them all laugh!

Despite getting the names of the artist and the piece mixed up, Martyn clearly impressed them, and following another more formal audition in front of expert piper, Major Gavin Stoddart, he was accepted. I was in daily contact with Margaret at this time, as she was one of my lecturers in the School of Scottish Studies, and I well remember her telling me the news that Martyn was about to start at Broughton. The offer of a place, though, seemed to come as a bit of a shock to Martyn himself:

I auditioned for a music school in Broughton in Edinburgh which was like the music unit there and to my surprise I got in on the bagpipes (laughs) and the flute. But I didn’t play any classical music – didn’t know anything about it. Couldn’t read or write music, I couldn’t really. It was much more an aural thing, an aural tradition to me, so it was quite brave of them to allow me to have my shot at learning formal music – classical training and I stayed there for three years and learned violin, piano, composition and to read and write music. And that was the most amazing three years and that was the point at which I realised this is where my talent lies.2

To this day, I find this one of the most incredible aspects of Martyn Bennett’s story. He arrived, aged 14, having had only the briefest of spells on violin seven years earlier, with only a very basic self-taught command of the piano keyboard, and with limited musical literacy. Yet by the time he left he was ready to walk into a classical musical performance programme at one of the world’s leading conservatoires.3