4,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Gill Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Assigned to a quiet corner of Ireland's most remote county, Martin Ridge was heading for retirement after a long career with An Garda Síochána, the Irish police force. All that changed when a call from a local priest set in motion what would become the most horrific sex abuse investigation the island had ever known. At Christmas 1997 a local priest Fr Eugene Greene reported to the Gardaí that a man had tried to blackmail him. This call, an act of hubris, set in motion a Garda investigation that revealed him to be a serial abuser of children. As word of the investigation spread, 26 men came forward. Most were from the tiny Irish-speaking parish of Gort an Choirce. All had been abused by Greene as children. Soon after, another man came forward to say that he had been sexually abused by a local schoolteacher, Denis McGinley. As Ridge dug deeper, he discovered that McGinley had been systematically abusing children in his classroom for decades. He had at least 50 victims. The Greene and McGinley cases both involved the Catholic Church. Greene was a priest, and McGinley a teacher in a Catholic school answerable to religious managers. As Ridge investigated, he discovered that the Church knew about the abuse, but ignored the problem. Brilliantly written and unsparing in its fidelity to the truth, Breaking the Silence is more than an account of a police investigation: it's the story of an entire community's struggle to come to terms with its betrayal by those in whom it placed the most trust.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2008

Ähnliche

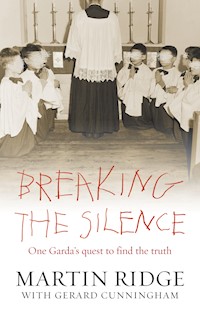

Breaking the Silence

Martin Ridge

with Gerard Cunningham

Gill & Macmillan

Contents

Cover

Title page

Preface

To protect the identities

Chapter 1: Blackmail

Chapter 2: A Trusting Time

Chapter 3: Where to Begin

Chapter 4: Under the Blankets

Chapter 5: Is it Money They’re Looking For?

Chapter 6: Up the Fire Escape

Chapter 7: Grapevine

Chapter 8: Weekend Visitor

Chapter 9: I Wish I Could Have Died

Chapter 10: What Am I to Do, Keep Moving Him Around?

Chapter 11: A Sculpture in Pain

Chapter 12: In the Shadows

Chapter 13: Coffee and Rosary Beads

Chapter 14: Nothing to Say

Chapter 15: Evil in Our Midst

Chapter 16: Getting the Full Story

Chapter 17: Brothers

Chapter 18: Part of Growing Up

Chapter 19: No Written Record

Chapter 20: He Will Never Make Much of Himself

Chapter 21: Permission to Talk

Chapter 22: Teacher’s Pet

Chapter 23: Teachers and Priests

Chapter 24: I Could Do Nothing About It

Chapter 25: The Health Services

Chapter 26: A Strong Case

Chapter 27: The Bureaucrat

Chapter 28: Museum Pieces

Chapter 29: Trip to Britain

Chapter 30: The Damage Done to Those Lads is Terrible

Chapter 31: Operation Alpha

Chapter 32: I Was Expecting You

Chapter 33: Guilty

Chapter 34: Shane

Chapter 35: Would You Investigate Your Own?

Chapter 36: The Tip-Off

Chapter 37: When is it Going to Court?

Chapter 38: A Good Teacher

Chapter 39: Sins of Omission

Chapter 40: Cha n-ólann Denis bocht is cha gcaitheann sé

Chapter 41: Moral Courage

Chapter 42: Missed Chances

Chapter 43: Cell System

Chapter 44: The Swallow

Chapter 45: The Day I Met a Miracle

Self-help contacts

Glossary of placenames

Copyright

About the Author

About Gill & Macmillan

Preface

This is a story of extraordinary betrayal and extraordinary survival which emerged when three separate child abuse cases surfaced almost simultaneously in a tiny corner of north-west Ireland. The cases involved fifty children and went back four decades. One of the abusers would prove to be Ireland’s most prolific rapist. The Gardaí launched what would be described as successful investigations, and prosecutions followed, but this was no ordinary criminal activity. Like an iceberg, just a fraction of the reality was ever on view.

I stepped into the investigation by accident. I was asked to assist detectives from another district because their investigation involved more than one district. I became involved in two further investigations when survivors of sexual abuse approached me with their stories.

Sexual abuse had already been in the headlines in Ireland. The aftermath of the Fr Brendan Smith case had taken down the government of Albert Reynolds. But this was my first encounter with it, despite a thirty year career in An Garda Síochána. I had seen the consequences of terrorism during those years, but nothing I had seen prepared me for the fall-out from sexual abuse. There was no training for this, no guidelines from HQ.

The story began at Christmas 1997 when a west Donegal priest, Fr Eugene Greene, reported to the Gardaí that a local man had tried to blackmail him. Instead, Greene himself ended in the dock. His hubris set in motion a train of events that led to two successful prosecutions. The lead detective in the first case also brought a third case to a successful end. I was assigned to the case because that detective, John Dooley, had worked with me before.

Among the survivors of sexual abuse, word got out of what was happening. Victims came knocking on my door — none would come to the Garda station — and my house became the unofficial nerve centre of the investigation. Those who came to me were grown men, most in their mid-thirties and most flooded with shame and guilt. Over the next two years I became accustomed to meetings in car parks, along lonely country roads, harbour piers — never in the Garda station. They didn’t want to be seen, and so we met in quiet deserted places, ironically often in the same lonely spots where many of them had been secretly abused years earlier. The shame stalked them as they told me the dark secret, almost as if in confession.

Listening to their stories, I was held in shocked silence. Of the twenty-six men who came forward about Fr Eugene Greene, I dealt with sixteen, all from the tiny Gaeltacht parish of Gort an Choirce. I knew them, their wives and their parents. It was a curiously intimate investigation.

Not long into the Greene investigation, another young man knocked at my door and stood there half huddled in the shadows when I answered. ‘I was also abused,’ he said. His abuser was Denis McGinley, a local schoolteacher. McGinley had abused children systematically in his classroom over many years.

There were now three investigations running simultaneously. The third, in which I was also involved as victims approached me, was focused in Dooley’s district. The Greene and McGinley cases both involved the Catholic Church, since McGinley was a teacher in a Catholic school answerable to religious managers.

As we probed, we learned that the Church had been told about the abuse in both cases decades before. One family had made a report as far back as 1976. Nothing was done. As a devout Catholic myself with close relatives in the Church, this causes me difficulty to this day. One night, early on, when I still had difficulty accepting what I was learning, I found myself standing in front of a mirror in my home shouting at myself, reminding myself of my duty to believe these men and not to be diverted by any other loyalty. I remain shocked and distressed at the role of the Church.

The force offered no support to the handful of officers involved in these cases. In contrast to police forces in the UK including the PSNI in Northern Ireland, there was virtually no logistical support. In the end I bought my own computer and taught myself how to use it, attending evening classes in a local hall in order to prepare an investigation file for the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP). Neither was there any kind of professional support. At the end of the investigation when I asked for counselling, I was told I didn’t need it. Such support is routine in the UK. It was symptomatic of the Irish force’s attitude at the time. Maybe things have changed.

Of necessity the accounts in this book do not go into the full details of the horrors those young men endured while they were still children, but it is necessary to recount some of their experiences here in greater detail in order to show what lies behind by now familiar words like ‘sexually abused’, ‘molested’ or ‘interfered with’. Young boys mostly aged between 8 and 12 were repeatedly raped by their abusers. In some cases the abuse lasted for years. Victims described how they were forced to masturbate their rapists or endure the indignity of being masturbated by them; boys were forcibly stripped, held down and repeatedly anally raped so violently that they bled for days afterwards; or forced to accept or perform oral sex, in one case so violently that the victim almost lost consciousness. Boys had to suffer their abusers’ hands reaching inside their pants, touching their testicles and penis or anus and endure unwelcome hugs and kisses, often accompanied by the stench of stale alcohol. One young boy was effectively imprisoned for three days by his abuser.

More than anything else, this is a book about the victims, those who survived sexual abuse at the hands of Greene, McGinley and others, and their courage in coming forward and telling their stories. Without their courage, justice would never have been done. The same goes for their friends, families and spouses who stood by them and established support groups. To protect the identities of those victims, their families and their friends, aliases have been used throughout the book. Certain biographical and other details that might lead to their identification have also been altered. The names of other people in the book such as my fellow Garda officers, health board officials, priests and teachers are unchanged. The one exception is John Reilly, who was convicted in 1999 and who cannot be identified as his name was never made public in order to protect his victims.

There are many others whose advice and assistance were priceless in writing this book, not all of whom I can name here.

Thanks first of all to Fergal Tobin, Publishing Director, and all those at Gill & Macmillan for their encouragement and support in this project and for invaluable advice at crucial stages.

Darragh MacIntyre, a reporter with BBCSpotlight, lived for several years in Gort an Choirce and got to know as well as I did many of those who were sexually abused as children. His own investigations for Spotlight uncovered new information that highlighted the extent of the scandal within the Church. It was he who introduced me to Fergal Tobin.

John Dooley, who worked closely with me on these cases, was an inspiration with his professionalism and attention to detail. To him and to the other Gardaí who worked on these and other cases, my thanks and appreciation, along with their counterparts in the health services.

Gerard Cunningham provided insights into the workings of the Morris Tribunal, in which forum John Dooley came forward, as well as advice on how to structure this book.

I would also like to thank the many priests who provided valuable background and insight and who sometimes were just willing to listen.

This book, and the investigations it recounts, would never have been possible without the strength and courage of the survivors of sexual abuse who came forward and told their stories, and their families. I cannot name them here, but to each of them, my eternal gratitude. I would also like to thank Colm O’Gorman, the director of One in Four, whom I had the privilege to meet several times.

Finally this book would not have been possible without the patience and understanding of my wife Brid and my daughters Aoife and Cliodhna. And I would like to thank my granddaughters Ailbhe and Síofra for their bright smiling faces.

To all of you, for your patience and dedication as I talked to you through a torrent of anger and horror, my thanks.

Martin Ridge

February 2008

To protect the identities of the survivors of child

sexual abuse and their families in this book, names

and certain biographical and other details have

been changed.

Where aliases are used, they are indicated by the

use of italics. Any resemblance to actual persons

is purely coincidental.

Chapter 1

Blackmail

Father Eugene Greene rang John Dooley’s home first, but the Glenties-based detective garda was at work. He left a number and a message, and Dooley’s wife phoned the Garda station to pass on the message.

It was just before 10 p.m. on the last Saturday before Christmas, 20 December 1997, when Dooley phoned back. Greene was a priest living in semi-retirement in the nearby town of Anagaire (Annagry). The priest told Dooley he had been the victim of a blackmail attempt. Dooley arranged to meet him the following afternoon and take a statement.

At 3 p.m. on Sunday, 21 December, Greene called to Glenties Garda Station and asked to see Dooley. Greene told him that the previous spring, on 15 April, he was in his home when the doorbell rang at around 6 p.m. He answered the door and found a young man standing there.

‘Do you recognise me?’ the young man asked.

‘No,’ Greene answered.

‘I’m David Brennan from Leitir,’ the man told him. ‘You did something to me. I’ll be back next Monday and you better have the money. Otherwise I’m going to the Guards. You have the money next Monday or else,’ Brennan said, and left.

Brennan mentioned no amount, just ‘the money’, and he never said what it was the priest was supposed to have done, Greene told Dooley, adding, ‘I did nothing wrong.’ Brennan didn’t show up the following Monday as promised, and Greene heard nothing more from him for several months. Then, on 16 December, Brennan called to his home again.

‘Do you recognise me?’ he asked.

‘No,’ Greene replied again.

Brennan reminded the priest that he had called before in mid-April. ‘I’ll be back on Monday, and you better have five grand,’ Brennan told the cleric, ‘otherwise I am going to the Guards, then all Loch an Iúir (Loughanure) will know.’

Greene reported this confrontation to Dooley, but said he still didn’t know what it was everyone would know. He decided to call Brennan’s bluff and told him to go to the Guards. He said that Brennan never mentioned during either visit what it was he was supposed to have done.

‘I took David Brennan’s visit on 16 December 1997 very seriously when he demanded £5,000 from me,’ Greene told Dooley. ‘I considered how to deal with it for a few days. I came to the decision that I had no option but to report the matter to the local detective as I see this as blackmail.’

The following morning Dooley arranged to meet Greene in the car park of a local shopping centre. He handed the priest a small dictaphone and microphone to tape David Brennan if he showed up again. The detective also gave the priest his mobile phone number in case he needed to get in touch. That evening between 7 and 10 p.m. Dooley sat in his unlit car watching Greene’s home in case Brennan should show up. It was an uneventful evening. Brennan never appeared.

At 9 a.m. the following morning Dooley briefed Superintendent Jim Gallagher on the events since the first phone call from Greene. That afternoon, along with Detective Garda David Moore, he arrested David Brennan. Dooley gave Brennan the standard police caution as he arrested him, warning him that he was not obliged to say anything, but that anything he did say would be written down and could be used in evidence.

‘That bastard, Greene, sexually molested me,’ Brennan blurted out.

The detectives took Brennan to Glenties Garda Station for questioning. Once there, he freely admitted that he had visited the priest twice and demanded £5,000 because he was sexually abused by the priest when he was an altar boy in west Donegal in the 1970s. The detectives asked him if anyone could back up his allegation. The only people he had ever told were his wife Carol and his best friend, Alan Walsh, he informed them.

Dooley knew Alan Walsh, who as it happened worked near by. While Brennan was still in custody, Dooley left the station to speak to Walsh, who confirmed that Brennan had told him he had been sexually abused by Greene when he was a child. Walsh was willing to make a statement to that effect.

Two hours into his arrest, Brennan made a full statement after being cautioned, admitting his blackmail attempt and outlining the abuse he had suffered as an altar boy. As he made the statement he became emotional and upset several times as he relived the pain of his abuse.

Greene often asked David to come up to the parochial house after weekday morning Mass and make him a cup of tea. At first David only had to make tea and he enjoyed the job because it meant he got to skip some early morning classes in school. Then, a few mornings in a row, Greene brushed against David while he made the tea, his hand grazing against the boy’s penis. Finally one morning he took David to his bedroom and undressed him. David didn’t understand what was happening. The priest warned him before he left the parochial house not to tell anyone. ‘It’s our secret,’ he told the boy. ‘Only God will know.’

‘I was afraid to tell anybody about this,’ David told the detectives. The abuse continued for several weeks until he could take no more. He told his parents he was getting too old to be an altar boy. ‘I dreaded this sexual abuse but I was afraid to tell anyone about it because he had told me it was his and my secret and that God knows,’ he said. ‘The other reason I was afraid to tell it was because he was a priest. I always felt dirty and I still feel very ashamed about the abuse. This is the first time I ever told the full story. I never forgot the torture he put me through.’

In his Garda statement Brennan also named other altar boys who had served around that time. He told the detectives that the priest often sent him down to local pubs to buy bottles of whiskey. He said he hadn’t seen Greene after the priest left Leitir Mhic an Bhaird (Lettermacaward) until one day in 1997 when he attended a funeral. At that time he was building a home for his family and money was tight. ‘I felt that this bastard should pay in some way for all the abuse on me,’ he explained. That was when he decided to call on Greene and demand money.

Greene had told the detectives he had no idea why a stranger at the door was demanding money. David gave a fuller account. When the priest opened the door, he invited David into a small study.

‘Do you remember what you did to me as an altar boy in Leitir Mhic an Bhaird?’ he asked.

‘No, what did I do?’ Greene replied.

‘You fucking bastard, you sexually abused me when I was an altar boy in Leitir Mhic an Bhaird,’ he told the priest.

‘Ah no, I never did that,’ Greene answered.

‘You lying bastard, you know rightly that you did it,’ David shouted, rising out of the chair in anger. He told the priest he was stuck for money and he would be back in a few days. He didn’t follow up on it though until shortly before Christmas when he called again to the priest’s home. Finances were stretched to breaking point finishing his new home, and his wife had spoken about cashing in her life insurance policy to pay the deficit. David didn’t want her to lose the investment.

The priest again denied he had abused David and pleaded poverty, but David was having none of it. He told the priest he could get the money off the bishop, or he would make sure everyone in the county knew what had happened. It was an empty threat. David had already thought about going to a solicitor about the abuse he had suffered, but couldn’t face the thought of having to tell someone else what had happened. As it transpired, his wife cashed in her insurance policy, solving the money crisis, so he didn’t bother going back to the priest for the money.

‘I would like to see this matter fully investigated and see that Fr Greene is brought to justice,’ David told the detectives. ‘I am willing to assist the Gardaí in any further enquiries in relation to my abuse. I can only say I regret demanding money from Fr Greene and I give an undertaking that I will not call to his house or approach him at any time again.’

‘He had great difficulty in telling the details of the many incidents of sexual abuse inflicted upon him by Fr Greene in the parochial house’, Dooley wrote later.

Brennan was released from Garda custody that evening while Dooley considered what to do next. A simple blackmail case had turned into something much bigger.

Chapter 2

A Trusting Time

I joined the Guards on 29 December 1966. I was 19 years old. I’m from Connemara, one of what was a typically large family at the time. I was wedged in, number seven of a family of ten. My mother had a total of fourteen children, but two were stillborn and two more died in infancy.

We lived beside Costelloe Lodge where the gentry came fishing. Bruce Ismay of Titanic fame built the lodge in the early 1920s. Just as an iceberg had taken so many of the Titanic’s passengers’ lives, sometimes I think that what I later discovered in Donegal was like an iceberg: it destroyed so many lives and yet we only came across the tip of it, the one-tenth above the surface.

We were the fifth generation to live in the house. My father had a drink problem and we were evicted from that house when I was 7 years of age. I remember coming home from school one evening to see Joe Mór’s big lorry pulled up at our house. We were being evicted by the owners of Costelloe Lodge.

Joe Mór’s red lorry was packed with furniture and other belongings. We were moving to our new unfinished house beside the pier at Derrynea. I don’t remember my father being there; I think he was working in England at the time. My mother was at home with us, a tower of strength to all ten of us. At the time, for someone in a small rural community like that, there was intense shame in being evicted. The cultural memory of the Great Famine and the shame of pauperism were still very real. The insecurity of that moment when we lost our home stayed with me for many years. We found somewhere else to live though our new house wasn’t completely plastered on the inside when we moved in. But what I had to deal with in Donegal was far worse. The victims I met there lost their innocence.

Emigration was rife when I was growing up. All of my father’s five brothers and two sisters emigrated to America bar one — Uncle Paddy joined the British Army and was attached to the Irish Guards. He was killed in North Africa in April 1943 at the age of 28. The number on his tombstone reads: 2718348 Guardsman. My brother Tomás visited his grave and brought me back a picture of this tombstone. I never saw or met my other uncles, with the exception of my uncle Val who joined the Chicago Police Department and came home a number of times. He was a romantic figure to me when I was growing up, a living connection with the world of gangsters in comic books and films, and I think the stories he told us on his holidays were part of the reason I decided to join the Guards.

When I joined the Gardaí in December 1966, there were two December classes; about 300 of us entered the Garda College in Templemore that month. Training lasted six months: ninety lectures to study and three exams. Having been brought up a native Irish speaker, it was the first time in my life that I had to speak English full time. I was very conscious of that. If I made a mistake in Irish hardly anyone would notice or mind, but if I made a mistake in English everyone noticed. My English was quite good, although I found I was thinking in Irish and translating it into English before I spoke. But I got used to it after a while. There was a lot crammed into those six months: marching on the square, physical training in the gym and swimming, learning police duties. Wake-up call was at seven every morning. Breakfast at eight consisted of porridge or cereal and hardboiled eggs. The dormitory floor had to be polished every morning, bedclothes folded neatly before we assembled on the square at 9 a.m. with shoes sparkling, uniforms neatly brushed and a very tight haircut. We had to get a haircut at least twice a week.

After Garda training in Templemore, my first station was in Milford, Co. Donegal. I was there from 1967 to 1973. I was only a few weeks in my first posting when I met my future wife. One of the Guards in Milford was doing a line with a girl from An Fál Carrach (Falcarragh), and he asked me to come along with him to a dance in the town. I can’t remember who was playing that night, but it was the first time I met Brid.

Brid was studying to be a teacher in England. We got to spend time together during the summers and at holiday times and kept in touch by writing to each other during term. Nowadays it would be all e-mail and texts, of course. I remember one night I drove her home from a dance, and on the way back my car broke down. I saw a light in the distance and went up to the house and knocked at the door. When the owner opened the door I told him my tale of woe. I was a Guard; my car had broken down; could I make a phone call. I wasn’t in uniform obviously and I didn’t have any Garda ID, but he gave me the keys of his brand new Ford Cortina and told me to bring it back later. It was a different world, a trusting time.

I hated drink because I saw what it did to my own family. I swore I would never drink, but there was a football tournament in Conway and the cup came around afterwards. ‘Go on, young Ridge, have a slug of it,’ someone said. Within eighteen months I was hooked. I don’t know if it was the stress of the job or something I inherited, but dealing with drink has always been a problem for me, sometimes more than at other times. There were a lot of things I didn’t like about myself back then. Eventually I was lucky enough to find Alcoholics Anonymous. I have fallen off the wagon a few times but I’m sober now, thank goodness.

In 1973 I was transferred from Donegal to the Midlands. Brid joined me a year later and we got married. While we lived in the Midlands she taught in the Christian Brothers School in Portarlington. She is teaching at Caiseal na gCorr (Cashelnagore) now. She didn’t pass the music exam in Ireland when she went for teacher training here, but she trained in England. It was one of those quirks I could never make sense of. She couldn’t get into training here because she couldn’t meet the Irish standards; yet once she got her degree in England she could apply to teach here. She had to do the Irish language test of course, but she is a native Irish speaker, just as I am and our children; it’s something we were proud to pass on to them.

I was stationed in Portarlington from 1973 until 1980, working regular uniform duties. Portarlington Garda Station is close to Portlaoise, the biggest prison in the Midlands, perhaps the biggest in Europe. It held the top subversives in Ireland at the time. The IRA was a constant menace during my time there. One of my colleagues, Garda Michael Clerkin, was blown up in an explosion in October 1976. I think that was the worst day of my career. I remember picking up bits of his flesh at the scene afterwards. The biggest part left of him was his ankle. He was identified by the initials ‘MC’ on his signet ring.

We were dealing with terrorism. The so-called ‘war’ was on in full force. People forget now how bad it was, with ceasefires taken for granted and endless talks of choreography and agreements. I remember when Shergar was taken, and the decoys and phone calls from the North. I remember the Herrema siege, the endless days of waiting and the relief when everything was resolved peacefully.

In 1980 there was a reorganisation within the force. The powers that be decided to set up a new detective unit, a divisional task force, as part of the Special Task Force. I was reluctant to apply as I was still battling the bottle. It looks simple to leave a drink down, but it’s not that easy. It gets a grip on you, consumes you. But when I wasn’t drinking I would do the work of two or three people to make up for lost time. My work rate must have impressed somebody because I was told to apply for the task force. I spent fourteen years with the detective unit in the Midlands.

In the early 1990s I transferred back to Donegal, to the station in the border town of Castlefin. Most of my time there was spent on checkpoints and border patrols, routine police work for the area, with the occasional day spent as station orderly. In March 1994 I was transferred to An Fál Carrach.

I enjoyed coming back to where I started, though it had happened more by accident than design. Brid had wanted to move back to Donegal with the girls for some time, and when an uncle left her a plot of land where we could build a home, it was a perfect opportunity. I was glad to be back. I grew up near the coast, and it was good to be living close to the sea again after years spent in the Midlands. I had a certain love for the area, the place where I started my career and where I got to know the people, where I had played football and won a county junior medal. There were memories I wasn’t so fond of too. It was the area that almost devastated my life as drink began to get a hold of me. It is hard to admit it, but I had a self-destruct mechanism inside and my mind was too hazy to see what I was doing to myself at the time. It was a trap, one I built myself, and hard to snap out of. Denial is a powerful force.

Around the time I came to An Fál Carrach, the BSE outbreak in England led to checkpoints for a different reason. The mad cow disease health scares meant we had to send out patrols to monitor cattle movements along the border and keep the country disease free after the government set up a ban on cattle imports. I was back in uniform again, back in Donegal where my career began, and only three years short of thirty in the force and approaching my 50th birthday. After my years in the detective unit I thought Donegal would be a winding down. I had done my share of hard policing, I had three years to go to my pension, and my girls were growing up. There was a small station party in An Fál Carrach — four guards and a sergeant. Steady as she goes to retirement, I thought. Donegal is beautiful, and An Fál Carrach is a particularly scenic spot, a small country station in the Gaeltacht. I couldn’t think of a more secure and safe place to bring up my two children.

There were routine traffic checkpoints to run, inspections of local pubs at night at closing time, and dole forms, passports and other forms to fill out occasionally for people who called to the station. Dole day was always a source of amusement and amazement to me. Each week I would find some of the forms lying on the hallway floor for me to sign when I arrived at work in the morning, pushed hurriedly through the station letterbox because the claimant was in a hurry to get to work too! It was a quiet duty for the most part. I had to deal with traffic accidents, a sight all too common on our roads, and there were about five sudden deaths in the area. Several prominent members of Sinn Féin own holiday homes in the area, including the Party president Gerry Adams, and part of my duties included keeping an eye on their homes when they were here, just to see if there were any interesting visitors. The peace process was well under way. The IRA declared a ceasefire at the end of August 1994, so as you can imagine there were a lot of comings and goings. There was a marked change in the atmosphere since my detective days in the Midlands. Instead of watching the ‘military men’ and trying to figure out what they were up to, now I was keeping an eye on the peace process and more likely to notice a politician in the area, from local town and county councillors to TDS. By 1997 I had reached thirty years of service. I could retire if I wanted to. But as our family prepared for Christmas 1997, something happened a few miles away that would change my life.

On Saturday, 20 December, at around 10 p.m. Glenties-based Detective Garda John Dooley got a message to make a phone call to a priest living in semi-retirement in Anagaire. The priest told Dooley he had been the victim of a blackmail attempt. John arranged to meet the priest the following afternoon and take a statement. The arrest a few days later of the alleged blackmailer, David Brennan, led to one of the most successful paedophile investigations ever undertaken by An Garda Síochána. Ironically we learned later that Fr Eugene Greene first contacted Dooley after speaking to a solicitor who advised him to report the extortion attempt to the police. Somehow I doubt that Greene told the solicitor the full story when he asked him for advice on what to do, but either way his decision to report the incident illustrated his sense of absolute untouchability. Perhaps that sense of being above the law led him to feel that because of his clerical status the Gardaí would never investigate him. Whatever his reasoning, it is a perfect example of what the ancient Greeks called hubris, that particular mix of pride and arrogance that always comes before a fall, blinding him so that he could not see ahead to what would inevitably follow once Dooley began his investigation.

I was assigned to the case in January 1998. We got Greene’s CV from the bishop, a history of his career. Greene had worked in Gort an Choirce (Gortahork) parish for several years, and my job was to find out if there were any victims on my patch. How do I start this assignment, I wondered.

Chapter 3

Where to Begin

Where do you start? You start with a casual conversation. My time back in uniform in Donegal paid off in a way I could never have foreseen when I transferred out of the Midlands detective unit a few years earlier. To the people who knew me in Donegal, I wasn’t some remote detective from a district or divisional office sent in to investigate a case. I was Garda Martin Ridge. I had lived and worked here long enough to become a familiar face, signed passport applications and dole forms, handled the occasional traffic checkpoint and closing time in pubs. I was married to a local woman, my daughters went to school locally, I knew a lot of the people and they knew me. I wasn’t a stranger; I was someone who could strike up a casual conversation.

I had worked with Detective Garda John Dooley on other operations over the years and I had a sense of what he was like. He had a reputation within the force for being a hard and diligent worker. I felt I could rely on him and I wasn’t let down. His dedication to the work in hand was second to none. We both had detective branch experience and he still worked there. We gelled together well.

An Garda Síochána is a national police force with the country divided into six regions, each headed by an assistant commissioner. The northern region, like all the others, was divided into several divisions, including the Donegal division. The chief superintendent in charge of the Donegal division had his headquarters in Letterkenny. He oversaw several districts, each headed by a superintendent.

My area in Donegal was the Milford subdistrict of An Fál Carrach, the Gaeltacht area to the north-east of Errigal Mountain known as Cloich Cheann Fhaola (Cloughaneely), which included the rural parishes of An Fál Carrach and Gort an Choirce. The two towns are barely two miles apart, but their hinterlands cover a wide rural area. My Garda station in An Fál Carrach covered both parishes, both the towns and the outlying countryside. Cloich Cheann Fhaola is sparsely populated, but in area is the second largest Garda subdistrict in the country. Toraigh (Tory) and Inis Bó Finne (Inishbofin), two islands a few miles off the Donegal coast, were also part of the parish of Gort an Choirce. Toraigh was still inhabited all year round, but Inis Bó Finne was empty most of the year, although some of the islanders still went out there for their summer holidays.

Dooley brought me in on the Eugene Greene case when he found out that Greene had worked as a curate in Gort an Choirce for five years between 1976 and 1981. Although I was in the uniformed branch of the force, I had worked with him on a few cases since I got back to Donegal because of my detective branch experience. John knew I had been based in An Fál Carrach for a few years and had a fair grasp of the area. I knew a lot of young men of the right age to have been altar boys at that time. Most of them would have been in their early twenties by then. A conversation between Dooley and his superintendent, and a phone call to me from my superintendent, ending with the brief instruction to ‘give John a hand on this’, meant I was assigned to one of the most complicated and harrowing investigations of my career.

I put myself more or less on standby. At first I saw my task as no more than having a cursory look around the parish. We had Greene’s CV from the bishop and I knew the time frame I had to deal with. I already knew Greene. I knew he was fond of a drink, but I was no stranger to that myself. I had often spoken to the man. He baptised one of our children in the mid-1970s. He was as drunk as a lord that day. Overall he seemed well liked. If anything, people felt sorry for him because of his drink problem.

I thought my task was to clear his name as far as the parish of Gort an Choirce was concerned. I couldn’t imagine anything untoward happening to children in this area. I had read about clerical sexual abuse scandals in other parts of the country and abroad; it had brought the government of Albert Reynolds down in 1994; I was aware of abuse in the Midlands; but surely it could not happen in this lovely place.

To begin, I did what Guards do: I talked to people — nothing fancy, just a chat whenever I met anyone. I would maybe talk about what the priest said at Mass the previous Sunday or about schooldays in Gort an Choirce, an easy enough subject to bring a conversation around to since my wife Brid worked as a teacher. Eventually you get to where you want to be in a casual chat. Do you remember Fr Greene? You’d have been an altar boy at the time, or maybe in a choir or youth club he supervised. What was he like? The response amazed me. ‘He abused me.’

It was like igniting a flame. Little did I know that the flame would turn into a furnace. I felt as if I was hit in a raw nerve. It was happening here too, I thought, but at the same time part of my mind still protested: it couldn’t be. I didn’t want to believe it. I wanted to ask him, are you sure? I felt like a footballer playing for two opposing teams at the same time. My loyalty to the Church dragged me to one side, yet here was a victim giving me gruesome details of child sexual abuse.

What do I say? What do I do? I listened. I knew he wasn’t lying, but I was ill prepared for his story. I could sense his shame and guilt as he blurted out his story as if it happened yesterday, every detail still fresh in his mind. The astonishing details were new to me, but not to him. I arranged to meet him later in a car park where he felt safe and could talk without worrying about being seen. He sat in my car, ducking whenever another car passed. The story gushed out with sadness and with some relief. It was agonising listening to him. This was his childhood, years of it, robbed and laid bare before us. He was ashamed of it. He was stagnating in hurt. I was shell-shocked at how fresh the details of the abuse were for him. He seemed to be reliving it as he spoke. Here was another tragic story kept buried for years due to fear, shame and guilt. All I could do was listen.

Dooley’s enquiries had led him to several more victims in other parishes. I sat in while he took their statements. Watching John, I learned from him and applied the same approach in my own area. This was a sensitive investigation, given the subject matter. So if you go to see someone, don’t go in uniform; go in plain clothes. Don’t use a Garda car, not even an unmarked one; use your own car. Go slowly; be patient. If people want to talk to you, they will, and if they don’t, don’t press them. Given what they went through, people are going to be reluctant enough to talk anyway. The last thing they need is a Guard throwing his weight around. So you talk and, more importantly, you listen and you wait. If people want to talk, they will come to you.

Somehow, despite the secrecy of the investigation and the sensitivity of the allegations, word had got out. Another young fellow approached me and told me he was abused. One case led to another. Each one I spoke to knew someone else I could talk to. Not everyone wanted to talk to me and there were false leads, but slowly we were able to build a case file. One young man, Edward Brown, flew over from England to speak to me. He later told his story in a television documentary. A friend of Edward was also abused by Greene, and after they spoke on the phone about the investigation, Edward decided to come home and speak to me too. Most of the victims had been altar boys. For many of them, being sexually abused was the norm, something they had had to accept as a part of growing up. The way the horrors they described were accepted almost as part of the culture of childhood shocked me.

But at least now they were talking about it. They seemed relieved to finally let the cork out of the bottle, although none of them ever came to the Garda station to talk. Instead, we met in hotel rooms or at my home or in a deserted car park. I think they forgot I was a Guard. I didn’t see myself as a policeman when I listened to them. Before this investigation started, they already knew me. I might have sworn a summons for them or taken care of a passport application or car tax. I dealt with them every day. They knew I would go down to the station for a form even if I wasn’t on duty if they were in a hurry. That’s the only explanation I can think of. I didn’t have any particular expertise in this kind of investigation. My experience in the Midlands, and in Donegal before and after the Midlands, had never prepared me for this.

When I was stationed in the Midlands I had encountered child sexual abuse only once, and then only indirectly. It was a Saturday afternoon shortly after I was appointed to the detective branch, and I found myself alone in the offices with nothing much to do. I noticed a key on the wall, and out of curiosity more than anything else I took it down and tried it on some presses. They opened. To pass the time I took out some of the folders in the press, a few old brown files wound up with twine and covered in dust.

I opened up one or two of the files. They were past cases. There was one dealing with a murder in the area, several major crime cases and a few reports on ‘subversive activity’. Then I came across one dealing with child sexual abuse in a local college. I was so shocked I almost dropped the file. I felt as if I was stealing something. The case involved a cleric who had sexually abused a number of young girls during the 1960s. The depravity of the abuse shocked me. How could anybody, let alone a person who was supposed to be minding young people, do such a thing? I felt so much revulsion that I still recall the shock, even years later.

For whatever reason the victims I met in Donegal felt they could trust me, and they also trusted John Dooley. The frankness of the responses, when finally asked what happened, sometimes stunned me. I would carefully bring the conversation around to Greene, or to childhood, finding the point to ask the question I needed: ‘Were you an altar boy with Fr Greene?’

‘I was, yeah.’

‘What was he like?’

‘Ah, he was after the lads.’ Most of them, I realised, had been waiting for years to be asked, living behind stoic outer masks.

After David Brennan was arrested and made the first allegations, Dooley and the local superintendent, James P. Gallagher, got in contact with the Raphoe diocesan office in Letterkenny and got their hands on a copy of Greene’s CV. With this they now knew every parish he had been stationed in since his returned from the missions. He spent his first ten years in the priesthood on missionary work in Africa. Since his return in 1965, he had worked in six parishes in Co. Donegal: Cnoc Fola (Bloody Foreland), Leitir Mhic an Bhaird, Gort an Choirce, Glenties, Gaoth Dobhair (Gweedore) and Cill Mhic Réanáin (Kilmacrennan). Apart from a year in Co. Cork (1969–70) and an earlier spell in Scotland, he had spent his entire career in west Donegal, mostly in the Gaeltacht parishes. Since 1994 he had lived in semi-retirement in Loch an Iúir. Armed with this information, Dooley had tracked down several men who were abused as children and we began the slow process of gathering evidence for a prosecution.

By mid-January we had spoken again to Alan Walsh, David Brennan’s best friend, and to David’s wife Carol. They provided us with formal statements confirming what they had told Dooley the day David was arrested. Alan, a 23-year-old salesman, had known David all his life. They became close friends when they worked together in their teens after leaving school, so much so that David asked Alan to be his best man at his wedding. A year later Alan returned the favour. Even though David had moved away since he got married, they had kept in touch and were still good friends. Alan told us that two years before, in the summer of 1996, they were both invited to the wedding of a mutual friend, where they got chatting over a few drinks.

‘I have something wild to tell you,’ David said.

‘Go ahead, talk away,’ Alan answered.

David hesitated for a while, and remained silent, toying with his drink. His eyes welled up and he wiped tears from his eyes. ‘I was abused when I was a wee boy on the altar in Leitir Mhic an Bhaird,’ he told his friend.