Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

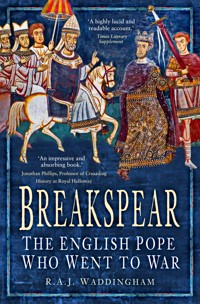

'A highly lucid and readable account.' – Times Literary Supplement 'An impressive and absorbing book.' – Jonathan Phillips, Professor of Crusading History at Royal Holloway In over 2,000 years of Christianity, there has been only one pope from England: Nicholas Breakspear. Breakspear was elected pope in 1154, but his story started long before that. The son of a local churchman near St Albans, he would battle his way across Europe to defend and develop Christianity, facing turmoil in Scandinavia and the Moors in the Iberian Peninsula. But it was after he took the Throne of St Peter as Adrian IV that he would face his greatest threat: Frederick Barbarossa, who was determined to restore the Holy Roman Empire to its former greatness. In Breakspear: The English Pope Who Went to War, R.A.J. Waddingham opens the archives to tell the story of a man who rose from humble beginnings to glorious power – and yet has been all but forgotten ever since.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 536

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To Angela

Front cover illustration: Frederick Barbarossa greets Pope Adrian at Sutri in 1155. (Peter1936F/Wikimedia Commons)

First published 2022

This paperback edition first published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© R.A.J. Waddingham, 2022, 2024

Maps © FourPoint Mapping

The right of R.A.J. Waddingham to be identified as the Authorof this work has been asserted in accordance with theCopyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprintedor reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic,mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented,including photocopying and recording, or in any informationstorage or retrieval system, without the permission in writingfrom the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 141 2

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

List of Illustrations

Maps

Preface

Main Characters

PART ONE: NICHOLAS

1 St Albans: Rejection at the Abbey

2 Paris: Searching for a School

PART TWO: BREAKSPEAR

3 Provence: An Augustinian Canon

4 Catalonia: The Second Crusade in Spain

5 Norway: Reform of the Norwegian Church

6 Sweden: The Swedish Church

7 Denmark: A Futile Plea for Peace

PART THREE: ADRIAN

8 Rome: The Throne of St Peter

9 Beyond Rome: Surrounded by Threats

10 Sutri: Pope and German King Face Off

11 The Leonine City: Coronation of the Emperor

12 Benevento: A Victory of Sorts from Defeat

13 Ireland: Henry II’s Intended Invasion

14 Ferentino: Dealings with the East

15 England: Appeals to the Pope

16 The Patrimony: Strengthening the Papal State

17 Besançon: A Bitter War of Words

18 Lombardy: Milan Surrenders to the Emperor

19 Anagni: Thwarted by Death

Epilogue: Succession and Schism

Acknowledgements

Chronology

Notes

Bibliography

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

1 Pope Adrian IV. By kind permission of Hertfordshire County Council.

2 Medieval St Albans Abbey. By kind permission of the Friends of St Albans.

3 Breakspear and Becket on the Merton plaque, 2012. Sculptor Antony Dufort (moral right to be identified as the author of the work).

4 Abbaye de Saint Ruf at Avignon. Courtesy of Marianne Casamance.

5 Nidaros Cathedral at Trondheim. Courtesy of Erik A. Drabløs.

6 Frederick Barbarossa meets Pope Adrian at Sutri. Courtesy of Peter1936F, Wikimedia Commons.

7 The coronation of Frederick Barbarossa. Courtesy of Peter1936F, Wikimedia Commons.

8 The crown of the Holy Roman Emperor. Courtesy of Gryffindor, Wikimedia Commons.

9 Frederick Barbarossa. Courtesy of Florilegius/Alamy Stock Photo.

10 Castel Sant’Angelo in the Leonine City. Courtesy of Adrian104, Wikimedia Commons.

11 Adrian’s sarcophagus in the Vatican. Courtesy ofstpetersbasilica.info.

12 The high altar screen at St Albans Cathedral. Courtesy of Robert Stainforth/Alamy Stock Photo.

MAPS

Breakspear’s journeys 1100–59. This map depicts modern borders.

Twelfth-century England and France.

Twelfth-century Italy and the Mediterranean.

Rome in the twelfth century.

PREFACE

The English reader may consult the Biographia Britannica for Adrian IV but our own writers have added nothing to the fame or merits of their countryman.

Edward Gibbon1

Nicholas Breakspear was elected pope in 1154, choosing Adrian as his papal name. He is the first and so far only Englishman to sit on the Throne of St Peter. To be elected pope is an achievement at any time; to have been elected at a time when all of Europe, sovereigns included, were in thrall to the papacy is doubly so. That such an honour could fall to an Englishman of low birth is almost unbelievable. Nicholas Breakspear, born near Abbots Langley early in the twelfth century, perhaps around 1105 and probably illegitimate, was elected pope unanimously by the cardinals. Despite this great accolade, his fellow countrymen seem to have completely forgotten him: Gibbon wrote his complaint in 1789 and little has changed since. Apart from a seventy-eight-page cameo by Simon Webb in 2016 and a collection of most helpful academic essays edited by Brenda Bolton and Anne J. Duggan in 2003, there has been no biography of Breakspear published since that by Edith Almedingen in 1925.2

Most English people know about Thomas Becket, the murdered Archbishop of Canterbury, born in London to a minor Norman knight only a few years after Breakspear. Yet few in England today know anything about Nicholas Breakspear even though his story is the more remarkable. London abounds with monuments to England’s famous sons, but the capital has neither plaque nor statue to commemorate Breakspear. His family’s descendants are better known in England for brewing beer. The Brakspear Brewery was established by distant relations in Oxfordshire in 1711 and to this day its logo is a bee, copied from Pope Adrian’s seal. They appreciate the greatness of their ancestor even if the rest of England has failed to acknowledge him.

Bishop Louis Casartelli, an Edwardian biographer of Breakspear, wrote in 1905:

It is not easy to account for the comparative neglect into which the memory of this really great Englishman and great Pope has fallen among us.3

There are reasons. Becket achieved what he did within England, whereas Breakspear spent but few years in his home country and as an adult was out of England’s sight. Becket’s exciting story centred on his quarrel with the English King Henry II, and his dramatic murder when armed knights stormed into Canterbury Cathedral. This English political story stole the limelight while Breakspear was left unnoticed over in Italy, where he was apparently just doing mundane churchy things. His activities in another country could not compete with a gory murder on people’s doorsteps.

British interest in happenings in wider Europe started only much later when adventurism began, and the seeds of empire were being sown. Even then, British universities, the source of most of our historical research, remained focused on events directly involving Britain. British giants on the world stage were kings, soldiers and, later, colonialists. Breakspear was none of these, so even in these later years, he continued to be overlooked. Nonetheless, the pope was supremely powerful in the twelfth century when Christianity was the beating pulse throughout the western world. There were heresies from time to time, but these concerned the interpretation of faith rather than challenging Christianity itself. The pope had temporal power too, although much less than Germany, France, England or Spain, whose kings nonetheless all recognised the spiritual leadership of the pope. In an age when the powers of Church and state were intertwined, the pope’s support for a nation’s political endeavours was crucial. William the Conqueror invaded England in 1066 with full papal support (throughout this book I use 'German' to describe the former Frankish Kingdom). Even the mighty Emperor Frederick Barbarossa of Germany, intent on re-establishing the lapsed authority of the Roman Empire within Italy, craved papal support. He was desperate to strengthen his position in Germany by being crowned by Pope Adrian in Rome. King William I of Sicily had defeated Pope Adrian’s forces in battle but he still gave him generous terms in return for papal recognition of his kingship. Despite being greatly respected by his powerful peers abroad, English historians failed to recognise Pope Adrian’s importance or seek to scrutinise his life.

That Pope Adrian had to stand up to the powerful Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, and that Adrian’s reign lasted but five years whereas Frederick dominated Europe for thirty-five years, left Adrian vulnerable to after-the-event imperial propaganda. With no sympathetic historians to champion Adrian’s cause or balance the story, German historians were free to belittle Adrian’s achievements unchallenged and unfairly accuse him of deliberately sabotaging the close links between empire and papacy. Furthermore, the papal schism on Adrian’s death in 1159 clouded judgements. The full story has not been fairly told.

Perhaps Pope Adrian received less attention because, by the time writers from the eighteenth century onwards began analysing history, Breakspear’s memory was suppressed along with the Roman Church. Breakspear was a devout churchman but his legacy is not one of liturgy, or of the minutiae of canon law, and his exclusion is unwarranted. Adrian was one of the twelfth-century popes who exercised the most influence in the political affairs of Europe, leading armies into battle and making and un-making states and their rulers. Despite a schism, he handed the papacy on to his successor in better shape than he had found it. His political power tempered by strong integrity contrasts sharply with our age, when many politicians are seen to be unscrupulous. In 1896 the Manchester Guardian acknowledged Adrian’s power:

There is no more striking illustration of the openings which the mediaeval Church gave to humble worth and ability that the like of a poor Hertfordshire lad who, leaving England almost penniless, came to reorganise the Scandinavian Church, to beard the mightiest monarch of Western Europe since Charles the Great, and himself to dispose of kingdoms.4

My second Christian name is Adrian. I have always been aware of my papal namesake, and my interest was piqued on a bike ride through Morden Park in London. A notice at the ruined Merton Priory claims that both Thomas Becket and Nicholas Breakspear attended its school. I tried to discover if these two Englishmen really had schooled together but found that there is no evidence that Breakspear was at Merton. Nonetheless, I had stumbled upon a gap in the pantheon of English heroes. Having spent forty-seven years working with numbers as an actuary, I decided to turn to letters and right this omission.

Nicholas Breakspear was a mystery to me before embarking on this project. I have scoured as much as possible from the sources available in English covering twelfth-century events. The monk chroniclers of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries provided background even though most had too little detail to satisfy the curious twenty-first-century mind. Two noted English chroniclers, Roger of Wendover and William of Newburgh, were both laconic. Contemporary writer John of Salisbury proved helpful and was refreshingly frank about his conversations with the pope. Notable by omission is the Laud Chronicle, the version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle that reaches 1154, which never deigns to mention Breakspear. It is odd that the election of an English pope seemed not to be newsworthy in 1154, although William of Newburgh, writing in the thirteenth century, was in no doubt about Breakspear’s impressive achievement:

He was raised as if from dust to sit in the midst of princes and to occupy the throne of glory.5

I might have expected more help from Matthew Paris, the chronicler monk of St Albans,6 writing 100 years after Breakspear, but he gave us not a word about Breakspear’s Scandinavian work, even though that had won for him the papacy. Fortunately two Scandinavian chroniclers, Saxo Grammaticus and Snorri Sturlason, offered some detail, not to say colour.

Adrian’s confrontations with Frederick Barbarossa dominated this period in Otto of Freising’s biography of Frederick, which was continued after 1157 by Rahewin. Both were partial to Frederick’s point of view but tell us much about events that we would not otherwise know. I am also indebted to the nineteenth-century writers Horace Mann, Alfred Tarleton, Edith Almedingen, Richard Raby and Louis Casartelli,7 whose hagiographies have taken me to places that I could not have reached on my own. John Freed recently wrote a weighty tome on Frederick which is well balanced on the all-important relationship between Adrian and the emperor.8

Breakspear: The English Pope Who went to War is not a religious essay and there are as many cannons as canons in his story. My aim is to delight the reader with a human story of an astonishing rise from a low birth in England to what was then the highest elected office in the world, an exciting tale set in a turbulent twelfth-century Europe. From his cradle in Hertfordshire to his grave in Rome, Breakspear’s life was a literal journey. There was effective free movement within twelfth-century Europe, especially for scholars, and people thought nothing of long travel even though it was so much harder than it is today. This account follows Breakspear’s footsteps through Europe and for most readers this is a journey into the unknown. Let us begin.

MAIN CHARACTERS

Anacletus II, Pope

When Pope Honorius died in 1130 two popes were elected: Innocent II and Anacletus, who was backed by the German Emperor Lothair III (1125–37). However, supported by Bernard of Clairvaux, Innocent won the recognition of most European countries. Anacletus died in 1138.

Anastasius IV, Pope

The 80-year-old Anastasius was elected pope in 1153 after the death of Pope Eugenius III. He reigned for only seventeen months, succeeded in 1154 by Breakspear as Pope Adrian IV.

Arnold of Brescia

Born in Brescia around 1090, Arnold was a priest who studied under Peter Abelard. He became radicalised and campaigned for the Church to renounce wealth. He became the leader of the rebel Commune of Rome and was hanged in 1155.

Bernard of Clairvaux, Abbot

Nobly born in Burgundy in 1090, Bernard founded Clairvaux Abbey in 1115. He defended the Church against heresy and was the driving force behind the Second Crusade. He died in 1153 and was canonised in 1174.

Boso, Cardinal

Boso was an Italian prelate serving in the Curia, and Cardinal of SS Cosma e Damiano from 1156; he died in 1178. He was chamberlain to Pope Adrian and one of his closest advisers.

Conrad III, King of Germany

Born around 1093, Conrad became King of Germany in 1138, using the title of Roman Emperor although he was never crowned as such. He died in 1152 and was succeeded by his nephew, Frederick Barbarossa. Together with Louis VII of France, he had led the disastrous Second Crusade.

Eskil of Lund, Archbishop

Born to an aristocratic Danish family around 1100, Eskil entered Church service in 1131, succeeding his uncle as Archbishop of Lund in 1137. A close follower of St Bernard of Clairvaux, he resigned his archbishopric in 1177, retiring to the Abbey of Clairvaux, where he died in 1181.

Eugenius III, Pope

Bernard of Pisa was born in 1080 and became a Cistercian monk at Clairvaux Abbey in 1138; he was pope from 1145 to 1153. He was a gentle man guided by his mentor, St Bernard of Clairvaux. Eugenius brought Breakspear into the Curia.

Frederick Barbarossa, Holy Roman Emperor

Born in 1122, Frederick was King of Germany 1152–90 and Holy Roman Emperor 1155–90. His forays attempting to restore imperial control in Italy dominated Adrian’s papacy.

Gregory VII, Pope

An Italian, born of peasant stock in 1015, Hildebrand of Sovana became Archdeacon of Rome in 1049 and reigned as pope from 1073 to 1085. He was a champion of papal supremacy, insisting that only the pope could appoint bishops.

Guido of Biandrate

An Italian count who controlled Novara, some 30 miles west of Milan, Guido was among the defenders of Milan in 1158 when it surrendered to Emperor Frederick. Nonetheless, he retained Frederick’s favour.

Henry I, King of England

The fourth son of William the Conqueror, Henry was born c. 1068 and reigned from 1100 to 1135. He seized the throne when William Rufus died in a hunting accident while his elder brother Robert Curthose was away on the First Crusade.

Henry II, King of England

Born in 1133, the son of Geoffrey of Anjou and Empress Matilda, Henry was the first Plantagenet King of England from 1154 until 1189, also ruling much of north-west France. He married Eleanor of Aquitaine after she had divorced King Louis VII of France.

Henry IV, King of Germany

Born in 1050, Henry was King of Germany 1054–1105 and Holy Roman Emperor 1084–1105. He sought to extend his control in Italy, pitting himself against Pope Gregory VII. The struggle between emperor and pope, centred on the power to appoint bishops, was called the ‘Investiture Controversy’.

Henry the Lion

Born c. 1129, Henry was Duke of Saxony from 1142 to 1180 and Duke of Bavaria from 1156 to 1180. A cousin of Emperor Frederick Barbarossa and a noted soldier, he married Matilda, the daughter of King Henry II of England. He died in 1195.

Inge, King of Norway

One of the three sons of King Harald of Norway, (1130–36) he was born in 1135 and nicknamed ‘Inge the Hunchback’. He ruled mostly alongside his brothers Eystein and Sigurd but outlived them both. He died in 1161 during a battle with his brother Sigurd’s son, who succeeded him as King Haakon.

Innocent II, Pope

Innocent II was one of two popes elected in 1130, and, with the support of Bernard of Clairvaux, eventually prevailed over his rival Antipope Anacletus II. He reigned from 1130 to 1143, spending much of this time in exile in France.

John of Salisbury

John Little, born in Salisbury around 1110, moved to France in 1136 to study in Paris and Chartres. He was a noted writer and philosopher and became a close friend to Breakspear. After 1148 he became secretary to Archbishop Theobald of Canterbury, and later Thomas Becket. He became Bishop of Chartres in 1176 and died in 1180.

Jon Birgensson, Archbishop

Jon was the Bishop of Stavanger when Breakspear arrived in Norway, and was chosen by the cardinal as the first Archbishop of Nidaros. He died in 1157.

Louis VII, King of France

Born in 1120, Louis was King of France from 1137 to 1180. His first wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine, later married King Henry II of England. He was joint leader of the failed Second Crusade.

Manuel Comnenus, Byzantine Emperor

Manuel was born in 1118 and ruled as Byzantine Emperor from 1143 to 1180. He was keen to restore the Byzantine Empire to its former glories and in particular to re-establish a hold on the Italian mainland and to oust the Normans from Sicily.

Matilda, Empress

Born in 1102, Matilda was the daughter of King Henry I of England and the widow of Emperor Henry V of Germany (1111–25). She later married Geoffrey of Anjou. She contested the English crown with King Stephen but it was her son, Henry II, who succeeded Stephen in 1154. She died in 1167.

Michael Palaeologus

A scion of a noble Byzantine family, Michael was sent to Italy by Emperor Manuel to regain former Byzantine holdings in Apulia on the Italian mainland. He died of natural causes during the fighting against King William I at Bari in 1155.

Octavian, Cardinal

Octavian was a member of the powerful Tusculum family in Italy, which had long supported the German emperors. He was appointed Cardinal of Santa Cecilia in 1151. After the death of Pope Adrian in 1159 a minority of the cardinals elected him Antipope Victor IV, with the strong support of Emperor Frederick. He died in 1164.

Otto of Freising

A German Cistercian and chronicler, Otto lived from 1114 to 1158. He was noble born, an uncle of Emperor Frederick Barbarossa and his biographer.

Otto of Wittelsbach

Otto was one of Emperor Frederick’s most loyal and leading knights. After Henry the Lion’s fall from grace in 1180, Frederick appointed Otto the new Duke of Bavaria.

Rainald of Dassel

Born around 1120 to the noble family of Dassel in Saxony, Rainald was a younger son who embarked on a career in the Church. Emperor Frederick appointed Rainald to be his chancellor in 1156. He always took a hard line in supporting Frederick.

Ramon Berenguer IV

Born c. 1114, Ramon Berenguer ruled as the Count of Barcelona from 1131 to 1162. In 1158 he became the effective ruler of the union of Aragon and Catalonia. In the Iberian part of the Second Crusade he led his forces in the capture of Tortosa from the Moors in 1148. He died in 1162.

Richard d’Aubeney, Abbot

Abbot of St Albans 1097–1119, Richard was probably the abbot who rejected Breakspear’s attempt to join St Albans monastery.

Robert de Gorham, Abbot

Abbot of St Albans 1151–66, Robert visited Pope Adrian at Benevento in 1155.

Robert Pullen

Robert was perhaps born in Poole in Dorset and lived from 1080 to 1146, becoming the first English cardinal around 1143. He had been a distinguished teacher of logic and theology in Paris, where one of his students was John of Salisbury.

Roger II, King of Sicily

Roger lived from 1095 to 1154; he was the son of Count Roger I of Sicily and the first Norman King of Sicily 1130–54. He bound the Norman conquests in Sicily and the southern Italian mainland into a strong, united kingdom.

Roland, Cardinal

Born in Sienna, and a teacher at Bologna’s university, Roland was appointed Cardinal of SS Cosma e Damiano in 1150. He was papal chancellor to popes Eugenius, Anastasius and Adrian, and led the cardinals who opposed Emperor Frederick. In the schism of 1159 most of the cardinals elected him Pope Alexander III.

Stephen, King of England

Stephen was a grandson of William the Conqueror, and was King of England from 1135 to 1154. His reign was unsettled as he had to defend it against the Scots and the Welsh and to fight rival claimants Empress Matilda and her son, Henry of Anjou.

Sverker, King of Sweden

Sverker, nicknamed ‘Clubfoot’, was King of Sweden from 1125 until his murder on Christmas Day 1156.

Sweyne III, King of Denmark

Sweyne was one of three competing kings in Denmark at the time of Breakspear’s visit in 1154. Born in 1125, he reigned from 1146 until he was killed by a rival, King Valdemar, in 1157.

Theobald of Bec, Archbishop of Canterbury

Theobald of Bec, in Normandy, was chosen by King Stephen to be Archbishop of Canterbury from 1139 until 1161.

Wibald of Stablo, Abbot

Born in 1098, William was a Benedictine and Abbot of Stablo in the Ardennes (in present-day Belgium). An influential member of Emperor Frederick’s entourage, William was always eager to maintain good relations between Frederick and Adrian. He died in 1158.

William I, King of Sicily

Born around 1120, the fourth son of King Roger II, William was crowned King of Sicily in 1151, three years before the death of his father. Unfairly nicknamed ‘The Bad’, he defeated attempts by disaffected Norman barons supported by Byzantine troops to seize his throne. He died in 1166.

PART ONE

NICHOLAS

1

ST ALBANS

Rejection at the Abbey

Breakspear, son to Robert [sic] Breakspear (a lay brother in the Abbey of St Albans) fetcht his name from Breakspear, a place in Middlesex, but was born at Abbots Langley.

Thomas FullerThe History of the Worthies of England1

In the year 1100, Henry Beauclerc was crowned King of England following the death of his brother, the unmourned King William Rufus. No more than a few years later, in the tiny hamlet of Bedmond in densely wooded Hertfordshire, a boy was born and christened Nicholas. There were few records of births then and none at all for peasants. Nicholas himself probably did not know his exact year of birth. Birthdays were celebrated by their proximity to one of the many Christian feast days – never very distant in the twelfth century, when no fewer than fifty holy days were marked – but many would not know which birthday they were celebrating. Low-born people did not refer to years in anno domini form, such as 1110, but rather anchored past events by how long ago they had happened. If in 1110 someone asked when Henry had been crowned, they might reply, ‘ten days before the Feast of the Assumption ten years ago’. Even members of the landed gentry might not know their exact age. Jury courts to establish ‘proof of age’ for the purposes of receiving inheritance or ending a wardship were not uncommon.2

The England into which this impoverished boy was born was different from the England we know today. A few of Henry’s subjects who had fought for the Anglo-Saxons or the Normans in 1066 would still be alive, a war less distant then than the 1982 Falklands War is today, but by the twelfth century the former antagonists were relatively settled, more than ready to enjoy the peace that the new King Henry and his Queen Matilda had brought.

We would not recognise the landscape, language, dress or customs of that time. The population of England was only about 2 million and most would have spoken Anglo-Saxon, or Old English, which, after the Danish conquest of the early eleventh century and the imposition of the Danelaw, had captured some Old Norse. The smaller governing classes would have spoken Norman French. This was when these two languages were starting to merge into the ancestor of modern English. The Victorian historian J.A. Froude remarked that perhaps the only twelfth-century sound we would recognise today is the pealing of church bells.3

Even the bounds of the English kingdom were far different from what they are today. Henry’s authority included the Duchy of Normandy from 1106, and later the rule of Henry II (r.1154–89) extended beyond the English shores to cover much of France, including Brittany, Anjou, Touraine, Poitou and Aquitaine. Within the kingdom, London had been England’s largest city since the ninth century, and by Henry’s time its importance had supplanted Winchester, having become the capital city under William the Conqueror (r.1066–87). Forests stretched out almost everywhere from the north bank of the Thames to St Albans in Hertfordshire, with rivers flowing in wooded valleys. Not yet had medieval England’s trees disappeared for building, agriculture and fuel.

While we may not know the exact date of Nicholas’s birth, we know that his father was called Richard Breakspear, although there has been some confusion over this. Matthew Paris (c. 1200–59), a famous monk chronicler of St Albans, wrote:

[Nicholas] was the son of a certain Robert de Camera who, living honourably in the world, moderately educated, received the habit of religion in the house of St Alban.4

Paris’s misnomer continues to this day in St Albans Abbey. In 1979, during archaeological excavations, the remains of Nicholas’s father, along with those of several medieval abbots, were relocated from ‘the column of the Cloister’ of St Albans and laid under the presbytery itself, in front of the high altar, where the commemoration stone bears the name ‘Robert de Camera’. Better sources now agree that Nicholas’s father’s name was in fact Richard, and he is recorded in the Canterbury obituaries as ‘Richard, priest and monk’.5

Although Nicholas’s father’s first name was wrongly recorded, it is possible that both surnames of Breakspear and de Camera could be correct. Camera was a known surname at this time, particularly in Devon, but it is more likely given here as a place name or a monastic office holder. In twelfth-century England it was not unusual for someone to be named after a place, or indeed by his occupation, rather than by his father’s family name.

At Harefield, south-west of Watford, on the border of Hertfordshire and Middlesex, there is an ancient seat of a Breakspear family. A Victorian biographer of Nicholas, Alfred Tarleton, lived at Breakspear House in Harefield and it pleased him to record a direct link from his house to the English pope.6 The surname Breakspear is unusual in England and this connection with Harefield is more than likely to be true.

Harefield, now a village in the borough of Hillingdon at the edge of the London sprawl, was then a small hamlet on the brow of a hill above the River Colne. The Domesday Book recorded it as a ‘five plough’ settlement. Just close by on the banks of the Colne was a preceptory named Moor Hall, also sometimes called by the Latin term ‘camera’. This was a small daughter house of St John’s Priory in Clerkenwell. While growing up in Harefield, Richard Breakspear may have had a connection to this nearby chapel and this could explain the name that Paris gave to Nicholas’s father. Richard had ambitions to enter Church life and it would have been quite natural for him to show a connection with a religious house near his original home.

There is another possible explanation. De Camera could have been a reference to Richard’s later role at St Albans Abbey, being a term used for a particular clerk in the abbot’s chamber. The camerarius was one of the officers of a medieval monastery and a relatively senior role, but it was not seen in records at St Albans until sometime later.*

Whether Richard Breakspear or Richard de Camera, or both, Nicholas’s father was the second son in his family. He may well have wished to stay in Breakspear House in Harefield, but the rules of primogeniture meant that the family home would be inherited by his elder brother. By the time he was of age, Richard Breakspear would have to leave Harefield and make his own way in the world, which he did, but he did not go far. Perhaps inspired by his experiences at Moor Hall, he may already have had an ambition to join a monastery so he travelled 12 miles north towards St Albans. Living near a monastery, among the traders who supplied it, would have been an attractive proposition, whatever his intentions, and he settled down at Bedmond, a hamlet beside Abbots Langley. Richard stayed in Bedmond for a few years but failed to make a better living for himself. It is possible that it was here that Richard met Nicholas’s mother and had Nicholas and his brother Ralph. If he was already a father by this time, the desire to provide for his family may have led him to improve his circumstances. Whatever the reason, sometime later he moved into nearby St Albans and became a serving brother at the monastery, although his actual status at the abbey is unclear. Richard eventually became the ‘chamberlain’, whose chief duties were concerned with the wardrobe of the monks. The chamberlain would examine their clothing and provide repairs or new garments when needed. He would also supervise the laundresses.7 This was a necessary and vital role, but hardly the high office that other writers suggested for Richard.

William of Newburgh (1136–98), by contrast to the other chroniclers, was less than complimentary about Richard. William was an Augustinian canon from Bridlington in Yorkshire and a contemporary of Nicholas who carefully documented as much information as he could about the famous fellow Augustinian that Nicholas would become. He was not impressed by Richard Breakspear’s position in life: ‘He had a certain clerk of no great skill as his father.’8 By calling Richard a ‘clerk’ of the abbey, William implies that he was ordained, albeit in minor orders. Richard probably started at the abbey only as a servant or lay brother, as Thomas Fuller recorded. Nevertheless, he would have shared a comfortable life with the other monks. Few then lived as well as the men in a monastery. Good sanitation, warm rooms and regular meals were luxuries to which few others could aspire.

While Richard was living comfortably in the monastery, it is not clear what happened to Nicholas, Ralph and their mother. We do not know if Richard ever married Nicholas’s mother or what became of her. She may have died before Richard joined the monastery. Historical records of men are sparse, and there are hardly any at all for women. It would not have been unusual then for a minor cleric to be married; nor would it have been exceptional for a priest-monk to father a child after taking religious office, though it would carry a mark of shame. Paris does not suggest that Richard had any children out of wedlock, but even if it were the case he would not have wanted to sully the reputation of a fellow monk of St Albans. Whether true or not, rumours of Nicholas’s illegitimacy persisted throughout his life.9

Paris tells us that Richard dwelt in the monastery for fifty years. This could be another example of Paris’s lack of attention to detail. If he did live that long he would have outlived his son, which does not seem likely as, when pope, Nicholas never mentions his father. During Adrian’s papacy a delegation from St Albans visited him in Italy and his father was not a part of it, and nor did the delegation carry any paternal greetings. John of Salisbury (c. 1115–80) was one of the most reliable chroniclers of these times, and a direct contemporary and friend of Nicholas, yet he makes no mention of a surviving father either.10 We are left not knowing how long Richard dwelt in the monastery or when exactly he died.

Richard must have been a formative figure for the young Nicholas, but the absence of dates and Richard’s move into the monastery means we cannot be certain how much contact there was between father and son. Nonetheless, bearing in mind St Francis Xavier’s maxim, ‘give me a child till he is seven years old and I will show you the man’, Richard must deserve some credit for instilling in Nicholas a yearning for education, and his desire to play a role in the Church.

Richard Breakspear’s religious life seemed to impact his second son, Ralph, who also entered the Church. He became a clerk in Feering in Essex, a church under the patronage of Westminster, and later he became an Augustinian canon at Missenden in Buckinghamshire.11 Like his father, although he was in clerical orders, Ralph had at least one son who was also called Nicholas, presumably named for his uncle.

Boso (c. 1110–78), the first contemporary biographer of Nicholas, had served as an official in Church government, known as the Curia, since 1135 and became chancellor to Pope Eugenius (r. 1145–53). This Italian later became one of Nicholas’s closest collaborators, for which Nicholas rewarded him first by appointing him as his camerarius, papal chamberlain, and in the following year by raising him to cardinal. Boso’s Vita Adriani IV was written in the 1170s and, as he was both a close adviser and a friend, his biography can be regarded as reliable although sadly it tells us nothing of Nicholas’s early life.12 This may have been an agreed policy for official Church biographies of its leaders, born of caution following the unwelcome speculation about the parentage of an earlier pope, Gregory VII (1073–85).13 It may also have reflected that, unlike today, little importance was placed on someone’s early life.

English chroniclers tell us something of Nicholas’s youth. Paris describes Nicholas as ‘a handsome youth, fairly backward in clerical skills’, while Thomas Fuller (1608–61) tells us that Nicholas grew up near Abbots Langley in Hertfordshire.14

Abbots Langley, a village dating far back into Saxon times, is close to St Albans and, as its name suggests, was owned by the abbey. Like all villages of the time it would have been self-sufficient. Nicholas would have been familiar with all the wooded paths to neighbouring villages, and the direct road to St Albans, 5 miles to the north-east. The Domesday Book was written around 1086, only thirty years or so before Nicholas was born, and the entry for Abbots Langley gives us a measure of what was then a tiny place:

Households: 10 villagers. 5 smallholders. 2 slaves. 1 priest. 1 Frenchman.

Ploughland: 15 ploughlands. 4 lord’s plough teams. 1 lord’s plough team possible. 10 men’s plough teams.

Other resources: 2.5 lord’s lands. Meadow 5 ploughs. Woodland 300 pigs. 2 mills, value 1 pound.

Annual value to lord: 10 pounds in 1086; 12 pounds when acquired by the 1086 owner; 15 pounds in 1066.15

Even the larger St Albans, a metropolis of its day, then had only ninety households. It would have been marvellous if the Domesday Book had given us names, but it does not. It was not a census as we now know it. Everybody in Abbots Langley and the adjoining hamlets would have known each other well and a couple of those Domesday Book villagers might still have been alive, in their fifties, when Nicholas was growing up. They could have known the young lad well. It is unlikely that the priest mentioned was Nicholas’s father; however, it might have been the Frenchman who first aroused curiosity about France in young Nicholas. Might he have heard his first spoken French at home, long before he travelled to France?

One mile north of Abbots Langley, in Bedmond, about 2 miles north-west of the modern M1 and M25 crossing, there was a farmhouse called Breakspear’s. It was demolished in the 1960s to make way for a small crescent of new houses and all that remains there now is a rather mean concrete plaque commemorating the site’s historical significance. The farmhouse itself was undistinguished and of relatively modern brick. Parts of the inside were older, although unlikely to have been any earlier than Tudor, but it could well have been built on the site of the original home of Nicholas’s family. At the end of the nineteenth century a watercolour painting of Breakspear’s farmhouse was presented to Pope Leo XIII (1878–1903) and it is now somewhere in the Vatican, giving some weight to the authority that this was indeed Nicholas’s home.

Bedmond is still tiny. Even though it is within commuting distance of London, its population today is less than 1,000. It boasts just one inn, a village hall and a single convenience store. Its church, the Church of the Ascension, was built in 1880 and is a rare example of a prefabricated corrugated-iron church. The road signs at the entries to Bedmond mark the village as the ‘Birthplace of Pope Adrian IV’ but those signs, and the concrete plaque at the site of the farmhouse, are the only mentions of a man who achieved such an exalted position. There is a further plaque in the church of St Lawrence in nearby Abbots Langley: ‘About the date of the building of this present church was born Nicholas Breakspear.’ This Norman church was built around 1150 and Nicholas may have been baptised in the Saxon church that lies beneath it.

Nicholas was most likely living in Bedmond when his father moved into the abbey at St Albans, although we do not know how old he was at this time. Unlike today, even young children would often have had to fend for themselves. He would not have been allowed to live with his father in the abbey, so he would have spent his early years in Bedmond with his brother, Ralph, and their mother, if she were still alive. By contrast to Richard, their lives would have been anything but comfortable.

Brickwork did not become widespread until the fourteenth century and rural houses and barns were built from local timber with some undressed stone. Rural dwellings consisted of a simple wooden frame covered with wattle and daub, or clay. The dimensions of the building would have been limited by the span of a tree trunk holding up the roof, no more than about 5 yards wide. There was plenty of space for houses in the small hamlets and so they would normally have had just one storey and be open right up to the roof. There were no individual rooms and screens were used to partition areas. Typically, one half of the house was for the family and the other half for stores and animals. Roofs would have been straw or thatch, fastened with branches. Thatching did not last long but was easy to replace.

Houses had windows but these were never glazed, instead having some cover such as oiled cloth or wooden shutters. The only heat came from an open hearth consisting of not much more than a ring of stones in the centre of the house. There were no chimneys; instead, smoke went through a hole in the roof. Wood for fuel was collected from the forests, no doubt a daily chore for the two boys, and lit by striking sparks with an iron on a flint. At night the only lighting was crude, such as rushes dipped in oil or fat. Tallow candles were a luxury the Breakspears could not have afforded and the boys’ winter nights would have been dark and long.

Homes were bare. Furnishings were primitive, limited to beds, chests for what few clothes they had, a table and three-legged stools, which would stand more securely on the uneven earthen floors. Beds would have been at best rope or leather stringing on a wooden frame with rough cloth stuffed with straw to serve as a mattress. Simple pottery and wood would be used for bowls and pitchers. Everything that the two brothers would have had was basic, but resilient as all young children are, they would hardly have noticed their disadvantage.

Plumbing was non-existent. Only monasteries had running water. Water for a rural house would come from a nearby stream or from wells dug down to the water table and would have been collected in rough wooden buckets, another daily chore for Nicholas and Ralph. At first light every morning, they would dump their waste water on to the garden and walk to the well to fill their pails. Excrement was chucked on a midden and, once rotted, spread to fertilise the land. None of these modern indignities would have bothered Nicholas and Ralph; for them it was all part of the hard life of the rural poor. This was no idyllic childhood for the brothers but they would not have been unhappy.

The first thing we would notice if we were at Bedmond then would be the pervading smells; clothes and bodies were thick with the scents of cooking and smoke. As today, one’s status in life would have been obvious from dress. There was no fashion or colour in the brothers’ attire. Wool was the main textile, but clothes were also made from hemp or linen – textiles which rarely survive. Wool was tightly spun for hard wear, and so quite uncomfortable. These tough clothes would be passed down from one generation to the next and Nicholas would have spent his early years dressed in ill-fitting hand-me-downs. Shirts and underclothes were of linen, with a knee-length woollen tunic worn on top.

The brothers’ diet would have been monotonous and seasonal as there were few ways to preserve food. Eggs, as likely to have come from ducks and geese as hens, and dairy foods from goats’ and ewes’ milk, not just from cows’, were available for much of the year, although they were forbidden during Lent. The mainstay of a poor family’s diet was potage, a soup made from grain, white peas, onions and leeks, all grown around the house. Most villages had a shared bread oven, baking with wheat, barley or oats when available. In scarce times, flour for bread was ground from acorns or hazelnuts.

The young Nicholas would rarely have tasted meat and is likely to have gone without potage on some days. Such was his hunger, and his determination to survive, that after his father joined the abbey he would trudge the five miles to St Albans most days and ‘haunted the monastery for the sake of daily handouts’.16 Despite his growling belly, Nicholas would have thought nothing of the 5-mile hike, and in summer he would have enjoyed his pleasant walk over rolling fields and through woods north from Bedmond to the abbey. Not so in the biting cold of winter, but still worth it for the chance of food. The M1 and M10 motorways now intersect this route, leaving it unrecognisable from Nicholas’s day, but the soaring red kites that Nicholas would have observed on his journey have now been reintroduced.

It was thanks to the Romans that St Albans ever came to have a monastery for Nicholas’s father to attend, and for Nicholas to haunt. Verulamium, as the Romans called St Albans, was the second largest town in their British province. As early as the first century, Roman traders and artisans had brought to England news of a new religion that came to be known as Christianity. Some English people converted to this new religion, but it took root only slowly. Christianity required the rejection of all other gods, which the polytheistic Roman authorities would not tolerate. Consequently, Christians were persecuted throughout the Roman Empire, which kept down the numbers of Christians until 313, when Emperor Constantine first permitted Christian worship.

St Albans was destined to become a Christian centre thanks to its eponymous saint, the first Englishman to be martyred for his faith in 305. Details of St Alban’s martyrdom reach us through legend rather than archaeology. The story of a Roman soldier arrested for sheltering a Christian was passed through word of mouth until the Venerable Bede wrote it down in 731–32:

The blessed Alban suffered death on 22 June near the city of Verulamium, which the English now call either Uerlamacaestir or Uaeclingaceastir. Here when peaceful Christian times returned, a church of wonderful workmanship was built, a worthy memorial of his martyrdom. To this day sick people are healed in this place and the working of frequent miracles continues to bring it renown.17

Bede tells us that when Alban was executed his severed head fell to the ground, and so immediately did the executioner’s eyes. This miracle established the cult of St Alban and in the following centuries St Albans became a major pilgrimage destination as people sought atonement for sins or cures from illness. With such a steady flow of Christian worshippers, perhaps it is not surprising that St Albans claims to be the only place in England where there has been continuous Christian worship since Roman times. Colchester in Essex might challenge that: outside its city walls are the remains of a church which dates to 302.

As Christian worship grew in England, monasticism started to take off in the wider Church. Individual monks who had previously retreated from the world as hermits started to come to live together in communities. This practice developed in England too and marked the emergence of the first Celtic monasteries, although some of these ‘monasteries’ may have been no more than settlements of Christian families coming together for common security. Western monasticism developed further through St Benedict, who was born in Italy towards the end of the fifth century. His widely followed rule was severe but less harsh than the previous austerity of the hermit monks. Benedict’s rule required moderation in all aspects of monastic life, but he did insist that members of his communities put aside personal preferences for the common good. Absolute obedience to the superior was non-negotiable. Today we struggle with such absence of any right to reply but then it was accepted.

The Rule of Benedict found its way from Italy into England only half a century after St Benedict’s death, arriving with St Augustine of Canterbury, himself a Benedictine. Pope Gregory I, Gregory the Great (590–604), happened to see one day some captive Anglo-Saxons in the slave market at Rome and described them as ‘not Angles but angels’. To make sure that these ‘angels’ would reach heaven, Pope Gregory sent Augustine as a missionary to Kent. The decision had significant effect:

Never did a Pope resolve on an undertaking more big with consequences. Not only did the doctrine take root in Germanic Britain, but with it a veneration for Rome and the Holy See such as no other country had ever evinced.18

On arrival Augustine wasted no time in establishing the first English Benedictine monastery in Canterbury in 598, thus forging lasting links with Rome. After Augustine’s time papal legates would visit England regularly, and English kings and nobles, including King Offa of Mercia (757–96), made pilgrimages to Rome. It was Offa who initiated the Church tax of ‘Peter’s Pence’, called Romefeoh. This was a fee due to Rome that was widely paid in mainland Europe, and which Nicholas would later introduce into Scandinavia.

The importance of Rome to England was demonstrated when Alfred the Great went there as a child in the mid-ninth century. These English links with Rome became stronger still after the Battle of Hastings, William the Conqueror having invaded England under a papal banner. This may have caused the Roman pope to lose some popular sympathy among the Anglo-Saxon English, but any such resentment did not persist, and the Church retained its power and authority. People were true to the faith, living in an age when it was rarely questioned, and Nicholas was no exception. Still, the Conqueror could never have imagined that within 100 years of Hastings an English peasant boy would become pope.

After Canterbury, other monasteries followed. The abbey at St Albans was one of many Benedictine foundations in England and tradition claims it was founded by Offa himself in 793 on the site of the tomb of St Alban. The new Benedictine abbey, holding the shrine of Britain’s first martyr, gained steadily in prestige and throughout most of the medieval period it was England’s premier abbey. Successive abbots of St Albans missed no opportunity to capitalise on their stewardship of the shrine. The old Saxon pilgrim route from London to St Albans, Eldestrete, meaning ‘the old road’, can still be followed snaking through Wembley and Radlett to St Albans.

Pilgrims were encouraged to visit the abbey shrine regularly. In accordance with Benedictine rules of hospitality, monks received guests kindly. It made sense: pilgrims’ offerings were a vital source of their income. Learning flourished too, and the abbey’s scriptorium was renowned for the high quality of its books. Nicholas knew from an early age that the abbey could sustain his hunger for food and his ambition for learning.

The abbey continued to flourish until late in the ninth century, when it was ravaged by the Vikings, and it was only towards the end of the tenth century that the Benedictines were able to re-establish themselves at St Albans. The constant flow of pilgrims soon provided the monks with enough riches to rebuild their abbey. This the Benedictines did in some style. Their vast new Romanesque church, larger even than Canterbury Cathedral, was started under their first Norman abbot, Paul of Caen, on the site of King Offa’s old Anglo-Saxon church. The tower, built between 1077 and 1088, was particularly splendid and is now the oldest surviving cathedral tower in Britain. Unusually, the Norman builders used recycled brick and flint rather than stone, since bricks were readily available from the surrounding Roman ruins.

The church was completed by Paul’s successor, Abbot Richard, and its dedication took place on 28 December 1115, the feast of the Holy Innocents (or, as they would have said, ‘on the feast of the Holy Innocents in the sixteenth year of King Henry’s reign’). King Henry and Queen Matilda held their Christmas Court at St Albans and all the great and the good of the day were invited for the lavish celebrations, led by Geoffrey, the Archbishop of Rouen, and including Richard, Bishop of London, Roger of Salisbury, Ralph of Durham and many abbots and earls, both English and Norman.19 The procession to the new abbey church, led by the royal court and followed by the princes of the Church in all their pomp, provided once-in-a-lifetime excitement to the townsfolk.

Those attending the dedication of the new abbey were entitled to the ‘indulgence’ of an unspecified number of days’ remission from penance, a valuable reward in medieval times. All the neighbouring villagers benefitted from the feasting laid on by the abbey. Nicholas, a young teenager by now, would have been excited by these parties, which lasted until Twelfth Night, 6 January 1116. These momentous events perhaps sowed the seed of his ambition in the Church, and that of his brother Ralph too.

The new abbey was stunning. It had taken thirty-eight years to complete and the Benedictines had achieved a remarkable result. The walls then were covered in gleaming white plaster to protect against the weather (today they are plain, but still impressive). The abbey sits on a hill in an idyllic landscape, nestled in the south-eastern corner of the massive Diocese of Lincoln and astride the Roman Watling Street. The journey from London took only one day, and the view for travellers approaching the abbey was outstanding:

Its impressive physical position marking the highest site above sea level of any English Abbey and visible for miles in every direction.20

Modern development around the church, which only became a cathedral in 1877, has taken away some of the impact of the earlier distant view.

Monasticism in England peaked in the twelfth century. There were as many as 15,000 men in monastic orders from a population of 2 million, meaning that almost three out of every 200 men were monks.21 Many more men were tied to the monasteries by employment. The monasteries dominated all aspects in the life of the nation. Monastic life brought regular work. The monks set the standards in education and were the only producers of books. They provided refuge for the sick. By the time of the Reformation the monasteries had come to own about a quarter of all agricultural land in England. They had become a power to be reckoned with.

The disciplined approach in a monastery demonstrated the belief that this was the way to Christian perfection. Nicholas knew from his father the set daily routine for a monk, the canonical hours, and it was strict: ‘Seven times a day I praise thee’.* The day began soon after midnight with Matins, prayers and psalms held in the church. The second hour, Lauds, consisted of the early morning praises usually celebrated in song soon after Matins and before dawn. After Lauds the monks would return to bed. The third hour, Prime, was the early Mass at 6 or 7 a.m., meaning that the monks would have had about seven hours’ sleep, albeit broken. This first Mass would usually be attended by the servants and lay staff of the monastery. After Prime, the monks would have said their private prayers and then studied in the cloister. There followed a simple breakfast of bread, baked in the monastery, with weak beer or wine, water not being clean enough to drink. The Chapter Mass would be celebrated at about 9 a.m. after which the daily Chapter, a meeting of all the monks, would be held behind closed doors to discuss the business of the day. Terce was the mid-morning hour, Sext the midday prayer and Nones the mid-afternoon prayer. The final prayer of daytime was Vespers, which took place around sunset, and the night prayer, Compline, was held at about 7 p.m. It was only in the fourteenth century that a day was divided into twenty-four equal hours. At this time the length of seasonal daylight was divided into twelve hours, meaning that hours raced by in wintertime and the prayers were shorter then than in summer.22

This regime sounds harsh, but Nicholas would not have thought so. In those austere times monastic life was an attractive option, and broken sleep and strict discipline was a small price to pay for it. Joining a monastic community brought security, companionship and comfortable accommodation, even if the cloisters were cold. Food was provided and a monk could rely on the monastery’s hospital, if needed, and on care in old age. This attractive package explains why so many men chose the monastic life, although among those numbers there would have been some who felt a genuine divine calling to religious life.

Nicholas knew the abbey routine, but he was not part of it, much as he would have liked to have been. Instead, even as a youngster he would have had to play his part in the rural life of Bedmond. An exercise for schoolboys to translate into Latin gives a rare picture of the onerous duties of a plough boy around the time of the Norman Conquest:

‘What say you ploughboy, how do you do your work?’

‘Oh dear sir, I must work very hard. I go out at dawn, drive the oxen to the field, and yoke them to the plow. However hard the winter is, I dare not idle at home for fear of my master, and when I have yoked the oxen and fastened the ploughshare and coulter to the plough I must plough daily a whole acre or more.’

‘Do you have a helper?’

‘I have a boy who guides the oxen with a goad, and he also is hoarse with the cold and his shouting.’

‘Do you do anything else during the day?’

‘I have more to do than I have said, certainly. I must fill with hay the mangers of the oxen and give them water and carry their dung outside.’

‘Oh, oh! Your tasks are heavy ones.’

‘Yes, sir, they are heavy, for I am not a free man.’23

The teenage Nicholas would not have been too young to work the land and might have seen the abbey as his way out of a rural existence. Not for him a life following the plough. Whenever his chores allowed, he visited his father at the monastery to get food, standing outside the abbey waiting for handouts, dreaming of one day eating inside with the monks, never imagining the comforts he would enjoy as pope in years to come.

But it was not just food he craved: he also wanted a real education. Some basic schooling would have been offered in the village churches, but his family would not have had the money for it, and even if they had, it would never have been enough for him. He knew instinctively that he had the ability to learn, and ambition drove him. He knew that he had to become part of a Church establishment if he was to obtain the best education available.

Richard doubtless would have encouraged his son. He might have hoped that Nicholas could join him in the community, a reasonable ambition for a twelfth-century father. Paris tells us that Nicholas approached the abbot and asked to be accepted as a monk at St Albans, or possibly a cleric at one of the abbey’s outlying churches. The abbot, Richard D’Aubeney (r. 1097–1119), did give Nicholas a trial, but he did not pass muster: ‘Wait, my son, and work further at school, so that you may be better prepared.’24

Paris may have wanted to be kind to Nicholas in reporting his rejection as a gentle rebuff; other less kind reasons for Nicholas’s rejection are recorded. Bale said he was turned down because he was a bastard; Trollope suggests he was refused because he was a ‘bondman’, meaning a tied, unpaid servant of the abbey.25 Another possibility is that the abbey was only admitting young men who came with a ‘dowry’. This was one of the ways that the monasteries raised funds and there was no way the Breakspears could have found such monies for Nicholas.

William of Newburgh suggests that Nicholas was turned away from the abbey by his father, rather than by the abbot:

Since he [Nicholas], on the threshold of adolescence, was not able to attend schools because of his poverty, he haunted the same monastery for the sake of daily handouts. His father was embarrassed because of this, reproaching his sloth with biting words; denied all solace, he went away indignantly.26

The suggestion that Nicholas was thrown out by his father is repeated in other accounts. Although William of Newburgh is regarded as reliable, it is doubtful that Nicholas left St Albans in anger: it does not fit the picture of the Nicholas that emerges after he leaves England. Nor is it likely that he was slothful as a youth. He might well have left at the shame of his rejection rather than being driven away by his father’s anger. It is possible that William of Newburgh simply latched onto an easy explanation of how Nicholas might have come to leave England. William himself, writing later about Nicholas’s election as pope, drops the idea that Nicholas had been slothful and suggests he remembered his father and St Albans kindly:

With the concurrent wishes of all, Breakspear, taking the name of Adrian, assumed the pontificate. Not unmindful of his earlier instruction, and chiefly in memory of his father, he honoured the church of the blessed martyr, Alban, with donations, and distinguished it with lasting privileges.27