4,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Constabulary Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

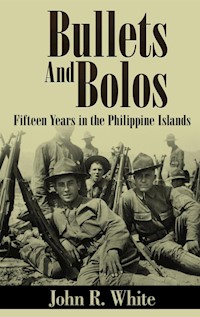

Bullets and Bolos is the memoir of Colonel John White's 15 years in the Philippines as a member of the Philippine Constabulary, the chief US law enforcement agency of the islands. The Constabulary was established in 1901 to quell unrest in the Philippines from native factions who had only just ejected their Spanish colonial rulers and were now faced with American occupation, as a result of the Spanish-American War.

John White took part in numerous engagements against the rebellious Moros on Mindanao and Jolo, including the infamous First Battle of Bud Dajo, and his assignments sent him far across the sprawling nation, whether to apprehended fugitives, interject in disputes or a myriad number of other dangerous policing tasks.

Bullets and Bolos provides rare insight into the culture of an American-occupied territory at the turn of the century, and is an engaging, lively tale about a vanished time and place.

*Annotations.

*Images.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Bullets and Bolos: Fifteen Years in the Philippine Islands

John R. White

Published by Constabulary Books, 2019.

Copyright

––––––––

Bullets and Bolos: Fifteen Years in the Philippine Islands by John R. White. First published in 1928.

Annotated edition published 2019 by Constabulary Books.

Original annotations copyright by Constabulary Books. All rights reserved.

ISBN: 978-0-359-57433-9.

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

1 - Soldier and Policeman

2 - Paymaster or Fighting Man?

3 - Tastes and Odors of the Tropics

4 - A Ball—and Some Reflections

5 - A Modern Don Quixote

6 - Genre Pictures of the Trail

7 - A Provincial Idyll

8 - A Night Raid by Outlaws

9 - Jungle Trails

10 - A Desperate Venture

11 - Deeper in the Jungle

12 - A Fight on a Mountaintop

13 - Murder, Merriment, and Morals

14 - Cholera in the Camp

15 - Floods, Amphibians, and Epidemics

16 - Disintegration and Reconstruction

17 - A Jungle Killing

18 - Damacio the Negrito

19 - Race Prejudice and Cattle Stealing

20 - A Senior Inspector’s Routine

21 - More Routine—Including Murder

22 - Bad Hiking and Worse Cholera

23 - American Pirates

24 - The Moro Problem

25 - A Tragedy of Zamboanga

26 - In the Spider’s Web

27 - Riflemen from Mud

28 - Bullets and Bees

29 - Life at Cotabato

30 - A Night Alarm

31 - Saved by Cicadas

32 - Datu Matabalo

33 - Oriental Eden Isles

34 - Talking for My Life

35 - Sailing the Sulu Sea

36 - Amok and Juramentado

37 - Bud Dajo

38 - From Warrior to Warden

39 - A Doleful Colony

40 - The Iwahig Experiment

41 - The End of a Tropic Day

Further Reading: They Call It Pacific: An Eye-Witness Story of Our War Against Japan from Bataan to the Solomons

1 - Soldier and Policeman

––––––––

ON JULY 4, 1901, WILLIAM H. Taft was inaugurated first American civil governor of the Philippine Islands. A temporary grandstand had been erected on the little plaza fronting the Ayuntamiento in Manila; and the rough board structure had been placed on huge blocks of stone that marked the foundations of a building begun by the Spaniards but never finished.

Those unused foundations were symbolic of that Castilian social and political structure that had crumbled when Dewey’s* guns roared over Manila Bay on May 1, 1898.[*Admiral of the Navy, George Dewey (1837-1917), led the attack on Manila Bay, during the Spanish-American War, sinking the entire Spanish fleet.]

In front of that grandstand, I watched the ceremonies that transferred power from General Arthur MacArthur [1845-1912], the military governor, to the civil authority; and saw a big, blond, painfully hot man inducted into a position as full of difficulties and stumbling blocks as could well be imagined.

Few men have perspired their way into the Presidency of the United States and its chief-justiceship, yet on that Philippine Fourth of July William H. Taft started a career which took him from a hot and cheap grandstand on the other side of the world to the cool and stately seat of the Chief Justice of the United States—via the War Department and the White House.

The crowd of spectators was not dense. There were a thousand or two Filipinos who should have been enthusiastically hopeful but were merely apathetic; a sprinkling of frankly sarcastic officers and soldiers, regular and volunteer; with a few, very few, American civilians who were largely employed by the military government but many of whom now found themselves automatically transferred to the civil regime.

For the most part the civilian onlookers were unconscious of being part of a historical event; ignorant that they were the nucleus of a civil service that was within a few years to work great changes in the allegedly unchangeable Orient. And least of all did I imagine that for thirteen years to come I should take a hand in the game.

It was perhaps fortunate that none of us at that time had read Sir Edwin [sic] Arnold’s thoughtful lines:

The East bowed low before the blast

In patient deep disdain;

She let the legions thunder past,

Then plunged in thought again.*

*[From Obermann Once More by Matthew Arnold (1822-1888).]

––––––––

US Army General Arthur MacArthur Jr.

––––––––

IF WE HAD KNOWN THE history of Eastern nations or had studied the relationship between Europeans and Asians, we might have been discouraged. But we were all young and we belonged to a young and hopeful nation. With firm and strong young hands which did not tremble we took the reins of government from palsied Spanish fingers; little did we reckon that we knew nothing of the temper or the mettle of the team we were to drive: Occidental Democracy and Oriental Autocracy.

After two years as a private and non-commissioned officer in the regular army, somewhat unprofitably spent in a Turkish-bath chase after insurgents over and through the rice paddies of Cavite Province, I had been discharged to accept a clerkship under the military government. I was twenty-one and, after the hardship of provincial hiking and fighting, life in Manila was good and full-flavored.

For that was the epoch still affectionately referred to by old-timers in the Philippines as “The Days of the Empire,” when thousands of soldiers, volunteer and regular, had transformed a sleepy old Spanish colonial capital into a fascinating palimpsest.

The principal business street of Manila, the Escolta, throbbed with humanity from every quarter of Europe, Asia, and America: officers and soldiers of the army, khaki-clad and often stained by the mud of trench and rice field; a diminishing number of Spaniards, flotsam of centuries of Castile’s rule and misrule of the islands; blue-robed and long-queued Chinamen who controlled practically all business but would now be forced to compete with hustling American men of affairs; tall Sikhs, much employed by banks and business houses as watchmen, and towering above the Filipinos who, with white camisas (shirts) hanging outside their trousers, were swept along in a current that already moved faster than before the American advent.

Most of the Filipinos were barefoot. Now there are few in Manila who go unshod. In that statement lies one measure of the changes of twenty-seven years.

Down the Escolta, drawn by a pair of native ponies, crept a toy tram and it was accompanied by diminutive victorias, quilez, calesas, carromatas, and carabao—gigs, buggies, covered vehicles, and water buffalo carts.

In the little vehicles, soldiers on leave sprawled their easy lengths and, when necessary for comfort, projected their legs to the driver’s seat. In many of the more pretentious victorias [elegant, French-style open carriages] sat women of all nationalities, with but a single thought—to relieve the soldiers of their pay, hard-earned among popping Mauser rifles but easily lost, amid the popping of corks, to the hetaerae [courtesans] who followed the army as sharks follow a vessel at sea.

Money flowed as easily as the turbid stream of the Pasig beneath the graceful arches of the Bridge of Spain [the Puente de España, linking Binodo and Santa Cruz]. There was no American so worthless but that he could secure a job of some sort with the army or the civil government.

For a month or two after my discharge, I lived in a “mess” in the Walled City—Manila proper. The old nomenclature of the city will probably fall into disuse, but in those days, everyone knew the Walled City as Manila, in contrast with other sections of the city such as Quiapo, Tondo, Binondo, etc.

Among a dozen of us young fellows, products of the latest civilization dumped down among the ruins of an Old World structure, were two ex-soldiers like me who hailed respectively from Georgia and Kentucky.

They were employed as clerks in the “Office of the Commissary-General of Subsistence of Prisoners,” or some such imposing title. Owing to the transfer of the Filipino prisoners to Guam, their work ran out, but their pay continued; and those two youths spent most of their time cooling their throats and searing their stomachs with highballs of rye and bourbon.

The superior merits of Scotch whisky as a drink for the tropics were in 1901 unknown to most Americans. However, when our national intelligence was focused on this subject a full knowledge of the brew of Bonnie Scotland was speedily acquired.

Anyhow, Smith and Brown, as we’ll call them, stuck to the liquor of their forefathers, spending their hundred dollars or so a month apiece on what they would call “a good old American drink, gentlemen—rye!” A hundred dollars in gold meant about 250 of the Mexican silver pesos current in the Philippines. A lot of whisky could be purchased for that sum. They went at it hard for weeks and by good teamwork avoided the provost guard.

However, one day I returned early from the office to find Smith asleep and affectionately embracing an empty bottle while a noise in the back of the building led me to the tiled bath on the flat roof, where I found Brown scrabbling around under the impression that he was pursued by a gigantic lizard.

And through the long thirsty years of tropical life ahead of me, the thought of that naked youth in the grip of delirium tremens often acted as a warning when the whiskies and sodas or the gin pahits (cocktails) were passed around too freely and too long.

Soon after the inauguration of civil government the need of an insular police force became apparent. The army, scattered throughout hundreds of small posts over the archipelago, was still engaged in hunting down wandering bands of insurgents; but the insurrection had degenerated into guerilla warfare of a particularly irritating nature, which bade fair to drag on indefinitely.

––––––––

The Puente de España, 1899.

––––––––

The bridge during the American Colonial Period

––––––––

THE ARMY HAD BROKEN the backbone of resistance to American authority; Aguinaldo* and most of the principal chiefs were captured, killed, or had surrendered; but scores of minor chieftains were in the field while the long-established bands of those brigands, with which the Philippines, like all Malay countries, was infested, had fattened during the insurrection and were now ravishing the fairest portions of the islands.

*[Revolutionary politician and later Prime Minister of the Philippines, Emilio Aguinaldo y Famy led Filipino forces first against Spain in the latter part of the Philippine Revolution (1896–1898), and then in the Spanish–American War (1898), and finally against the United States during the Philippine–American War (1899–1901).]

For the army to hunt down these small swift bands was like shooting snipe with a rifle. A native police force largely officered by Americans was needed; in fact, the army had already organized such a force under the title of Philippine Scouts.

But the rub was that the civil government did not control the Scouts and there was much friction between the civil and military branches.

The civil governor needed an armed force under his direct supervision, so on August 1, 1901, Act 175 of the Philippine Commission created the Philippine Constabulary.

Even now, thirteen years after my retirement from that little army, the name conjures up a flood of tender memories; of fights and friendships from Aparri to Bongao.

The Philippine Constabulary. Just two rather long words to most people, but as I write them tears almost come to my eyes as the thrill of loyalty to the old corps still wakes an echo in my mind; and I see through the mist of time and years the epic and the drama which we youths were to play in the cultivated lowlands and in the wild mountain jungles of those myriad tropic isles.

The Manila newspapers gave full accounts of the new organization which was to stamp out brigandage; we saw fledgling officers strutting around in all the glory of their red- and gold-trimmed uniforms; several of my best friends obtained commissions as inspectors and urged me to join.

But at first, I hesitated. The Constabulary was ridiculed by many army men and from what I saw of its first halting steps I doubted whether the service would be attractive.

However, the longing for further adventure decided me, and on October 18, 1901, I found my way through the narrow streets of old Manila to the first headquarters of the Philippine Constabulary on Calle Anda.

Behind a big narra table sat an army officer in civilian clothes: Captain Henry T. Allen of the United States Cavalry, detailed as Chief of Constabulary with the rank and pay of brigadier-general in the regular army. A few minutes’ interview with him, a look at my discharge from the army and other papers, and, lo, I was changed from a mere civilian to Third Class Inspector John Roberts White, P.C.

My salary was to be $900 United States currency per annum, which in my mind was quickly translated into its equivalent in Mexican pesos per mensis. I was promised an early opportunity to chase ladrones (brigands) in the Philippine bosques (jungles) and told where I could purchase a uniform of gray linen or cáñamo cloth, the gilt buttons, and the broad red shoulder straps with gold bars which were to adorn my youthful shoulders. I had just passed my twenty-second birthday and when I had donned those red shoulder straps the world seemed a very pleasant place.

Our uniform was gray cáñamo cloth because in those early days it was thought better that it should not too closely resemble the uniform of the regular army.

Much water was to run into Manila Bay before the jealousy between the army and the upstart Constabulary would be wiped out by memories of many a combined campaign in the swamps of Mindanao and the jungles of bloody Samar.

In 1903 the Constabulary adopted a uniform similar to that of the regular army and with the same insignia of rank. But instead of the promised excitement of outlaw hunting my first work was humdrum in the extreme. For several days I addressed the little books of instruction for the corps, ‘The Manual of the Philippine Constabulary,’ which from a pamphlet of few leaves grew within a few years to a substantial volume in which a Constabulary officer might find information on any subject, from filling out a requisition for kerosene to shooting a runaway prisoner.

Within a few days I graduated from this subordinate position to that of clerk for the Chief, whose civilian amanuensis was sick. My two or three weeks at this work gave me splendid opportunity to see the inside workings of the new organization. Some Spanish papers which the Chief gave me to translate compelled me to brush up on the Castilian language, the rudiments of which I had mastered a few weeks earlier by visits to a Spanish Augustinian friar who lived in the massive monastery that fronts Manila Bay.

––––––––

Emilio Aguinaldo, c. 1898

––––––––

Emilio Aguinaldo in 1919

2 - Paymaster or Fighting Man?

HOW INTERESTING ALWAYS are the first experiences, the first steps that count so much. Those were fascinating days in the office of the Chief of the Philippine Constabulary.

In and out passed the heterogeneous population of Manila: ex-soldiers and officers of the volunteer and regular armies seeking commissions; Filipino politicians establishing relations with the new branch of the government or forwarding the interests of Filipino members of the insular army; secret service agents with reports of new katipunans (secret societies) or the whereabouts of badly wanted brigand chiefs; army officers of high rank with complaints of usurpation of authority by agents of the civil government; Spaniards of all degrees, men and women, backwash from a wave that had spent its force, and who were now looking for employment or for passage back to Spain.

Early in the history of the civil government the Constabulary became a dumping ground for all work not clearly allotted by law to a particular bureau. All of these people the Chief urbanely met while at the same time supervising the task of organization with the distribution of men, supplies, arms, and ammunition throughout the forty-seven provinces of the archipelago.

The Constabulary was organized by provinces; a senior inspector commanded in each province from fifty to three hundred men with the corresponding number of officers. Within his province the senior inspector controlled the police and campaign work under the supervision of a district chief.

There were five districts each commanded by an assistant chief with rank of colonel and within his district the assistant chief had the authority vested in the Chief of Constabulary to see that brigandage, unlawful assemblies, and breaches of the peace were suppressed, and law and order maintained.

With some minor changes this organization of the Constabulary continues to this day and has worked satisfactorily. The principal modification has been the organization within provinces of companies of forty-six men each. This has facilitated supply, mobility, and keeping of records.

For a time yet I was to be retained in Manila, although I frequently requested the Chief to let me go to the provinces and take part in fieldwork. Every morning’s mail brought to the Chief’s desk scores of telegrams and letters reporting fights with outlaw or insurgent bands. As I read and distributed them, a great longing to get into the game again surged over me. I was eager to be doing things—not indexing and filing reports about those who did them.

One telegram would tell of a desperate fight in which the Constabulary came out victorious, killing many outlaws and capturing rifles, bolos (machetes), and ammunition. Another brief wire might say that Inspector So-and-So, perhaps commissioned a few days earlier, was shot or bolo-ed to death while fighting against odds. Yet another would tell of outlaw raids on the rich sugar haciendas (plantations) of some island far to the south and of Constabulary pursuit over mountains, up rivers, and through jungle. That was a fascinating mail bag, and it was a poor morning that did not report the capture or death of a score of outlaws.

With the inauguration of civil government, legislative alchemy had transmuted all insurgents into “outlaws,” and woe to the officer who reported “insurgent bands;” but by whatever name, they gave the Constabulary many a good chase and sporting fight. We felt little or none of that hatred of the enemy bred by propaganda and trench warfare during the World War. Rather we felt, after we had chased an outlaw chief for a few months through the jungle, a spirit of not unfriendly competition. But I am getting ahead of my story. These accounts of fighting and adventure awakened previous experience of war’s alarms, so that with all the ardor of youth I longed to be beside the gallant fellows who were almost daily meeting death.

One day a telegram came which read something like this:

Indang, Cavite, Nov. 20, 1901.

Chief of Constabulary, Manila.

While riding from Dasmarinas to Silang with two men I was attacked by band of six outlaws armed with rifles and bolos. We killed all six. Sent back detachment from Silang to bury outlaws.

Knauber, 2nd Class Inspector.

Knauber got a Medal for Valor for that. Such deeds soon gave the Constabulary needed prestige and made the red shoulder straps of its officers respected by all classes of Americans and Filipinos throughout that green string of islands that stretches from Formosa on the north to Borneo at the south; athwart a thousand miles of sapphire seas.

The Chief’s stenographer returned. My request for provincial service was met with the remark that, “We have plenty of men who can hike and fight but few who can be trusted to do clerical work.”

So, I was made assistant to the quartermaster, a young lawyer, Herbert D. Gale, who later rose to be Judge of the Court of First Instance.

For a few weeks, I ran around Manila buying supplies and acquiring intimate knowledge of the price and whereabouts of lamps, blankets, leather goods, dried fish, rice, and the thousand and one articles needed by the Quartermaster, Ordnance, and Commissary Departments.

It was interesting enough to dicker with the Chinese, Spanish, and other merchants while visiting out-of-the-way corners of the city on a hunt for needed equipment. A job lot we got. Most of it was scrapped within a few months. But it served to tide us over until systematic orders for supplies could be placed in the United States.

That purchasing job brought a few temptations in my way. With pay of about eighty dollars a month, the extravagances of life in Manila during the Empire Days made extensive demands on my slim purse.

Often, I found handsome presents from Chinese merchants—a case of whisky, a bed, a settee or other useful article—at my quarters; but my recollection is that I returned practically all of the presents. Memory is, however, dim about the whisky. There was in the Philippines to tempt our officials an inheritance of native Oriental venality, as well as the imported Spanish variety.

About the close of 1901, the Chief called me to his office saying that he intended to make me paymaster of the First District. Vainly I expostulated that I knew nothing of accounts. I could learn, said he. As sop to my vanity, promotion to the grade of Second Class Inspector was thrown in and for a very small mess of pottage I yielded. Promotion gave me one more gold bar and ten dollars a month additional pay.

That morning I awoke wondering where I could borrow a few dollars to tide me over until payday. That night I had a bank account of some eighty thousand pesos, with a safe in my office containing some thousands more of pesos in silver, all done up in sacks of matting. Not strange, indeed, that during the early days of our Philippine venture some young American disbursing officers went astray.

It was about that time that one young Constabulary officer situated like myself put a hundred-pound sack of government silver pesos in a carromata and boldly drove off down to the red light district. Of course, he ended in Bilibid Prison,* as did a score or so more Constabulary supply officers, provincial treasurers, and other disbursing officers of the government. The Spanish law applied to these crimes. The penalty for embezzlement of government funds was about fourteen years, one month, and a day—rather a long period in which to atone for one night’s strolling down an apparently primrose path.

*[The civilian penitentiary later became a notorious POW camp during the Japanese occupation of the islands during WW2.]

––––––––

Bilibid Prison in 1900

––––––––

IT WAS A GREAT PITY that more care was not exercised in the selection of officers entrusted with money responsibility, for the Filipinos got the idea that we were no better than the venal Spanish officials with whom they had hitherto dealt. Yet there was this difference: the Spaniards went back rich to Spain; the Americans returned to the United States in the holds of our transports after serving some years of imprisonment in Bilibid.

Often in after years when visiting that same prison, I would see American convicts about their daily tasks and think, “There, but for the grace of God, goes John White.”

My experiences as a disbursing officer were sufficiently interesting, for at the start I did not know the difference between a voucher and an account current. Indeed, my financial experience had hitherto been limited to the simple process of filling my pockets with money and emptying them again as soon as possible. But now I found a desk with wire baskets full of imposing papers which a friendly brother officer told me were vouchers waiting to be paid. It was a tall pile of vouchers left by my predecessor, who had himself absconded for parts unknown, taking with him as many Mexican pesos and United States bills as he could secure.

Hopefully, yet not without trepidation, I tackled that pile of vouchers. In after years the wall of many a Moro fort looked less high to me than that pile of vouchers, which came from every part of the island of Luzon, north of Manila. One voucher called for payment of fifty sacks of rice; the next was a payroll for a provincial Constabulary; yet another showed that an officer had hired a horse for a month at two pesos daily, and so on.

Regulations governing expenditures I had none; or if I did have, I did not know where to look for them. But I had a checkbook, almost unlimited credit, and the knowledge that poor devils of officers and men, sweating over the hills after outlaws, needed money and food. So, I buckled to the job.

I disbursed funds for about three months; and for about three years after my transfer I was kept busy explaining to the auditor for the Philippine Archipelago—a title as forbidding to us youngsters as it was resounding—just where the half-million pesos or so that I disbursed had disappeared.

If a voucher came in stating on the face of it, “Horse hire, $50,” I paid it. And that unreasonable auditor wanted to know where the horse was hired, for what purpose, and I know not what details omitted by the officer who had rented the native pony.

Sometimes I was tempted to ask if the auditor did not want to know the age, sex, date of birth of the animal, together with its color, marks, and pedigree.

After I had left Manila and was campaigning against the babaylanes (fanatical outlaws) in Negros, I received from the auditor my first list of suspensions. It was for more than $50,000, Mexican currency. Then for night after night, following strenuous days in the field, I was kept busy with atlas and papers making up journeys for officers and men whom I had paid months before in northern Luzon.

Thus, I came to have accurate knowledge of that part of the islands long before I visited it; for the auditor was so insistent as to dates, places, and facts, that often I had to supply them from an imagination keyed by taking part in similar scenes, and with the help of an atlas of the Philippines. How I blessed the Jesuit priests who compiled that atlas! Without it I might have been in Bilibid Prison.

More experienced brother officers to whom I shall ever be indebted helped me and instructed me in the rudiments of bookkeeping. But after a few weeks I was ready to resign; so, I respectfully told the Chief as frequently as possible that he had promised to let me go to the provinces. At last he listened to my plea.

One day he took from his desk a bundle of papers and walked across the room to a map hanging on the opposite wall. It was a blueprint of the island of Negros, one of the Visayas group, about three hundred miles south of Manila and noted for its big sugar plantations. Papers in hand and often referring to them, General Allen pointed out the centers of brigandage, spoke of raids on haciendas by bands of outlaws known in Negros as babaylanes, said that it was one of the most serious problems confronting the Constabulary, and that organization in the province of Negros Occidental was just beginning.

Then he ended by saying that I was to go down there to assist Major Orwig, the Senior Inspector of the Province, and that he expected that I would take active part in suppressing the outlaws and thus justify my relief as disbursing officer.

Treading on air, I left the Chief’s office. I was to become at least a supernumerary on the colorful stage of the Philippines, its properties the weapons of guerilla warfare, and its drop curtain often death.

As I threaded the maze of the Walled City back to my room overlooking the Augustinian monastery, the gray city wall, and Manila Bay, never had the streets seemed so full of happy people, the weathered tiles of the buildings so restfully red, and the tropic sky above those tiles so brilliantly blue. I was young and off on a great adventure.

3 - Tastes and Odors of the Tropics

A FEW DAYS AFTER MY interview with the Chief I handed over to my successor my balance of government funds, together with my blessing and a heap of unpaid vouchers. Whether the money responsibility or accounts were too much for him or what, I do not know, but within a few months my successor died; and I have often felt that a few more weeks of that financial strain might have killed me, while the bolos and bullets of the babaylanes and Moros passed me by.

Then one day I packed my humble belongings in a tampipe (straw suitcase), strapped a heavy Colt single-action .45 revolver around my waist, took a .44 Winchester repeating rifle in my hand, and started south. That Winchester was to shoot my way through many a tight hole. As I write, it hangs on the wall, reminder of a score of jungle fights, and on the stock are several notches which, boy-like, I made when outlaw chiefs fell before it. Those who were not chiefs went unnotched.

I was off for the southern Philippines. First came the steamer voyage to Iloilo. Some old-timers may remember the good ship Francisco Pleguezelo, which in those days linked Manila with the Visayas Islands to the south. We were not then as critical of transportation as American supervision of the inter-island steamers has since made us, or we would have complained of the accommodations more bitterly and resultantly than we did.

She was a craft of some four hundred tons burden, and indescribably dirty. To sleep in her cabins was an adventure. Huge cockroaches, inches long, black, greasy, and evil-smelling, infested walls and bedding. At night they roamed over the somnolent voyager, and until he learned to go to bed with his socks on, they browsed between his toenails, so that paradoxically enough sore feet often resulted from a steamer voyage.

Although it was hot meandering down between the islands at a speed of from seven to eight knots an hour, yet the only way to get a bath was to arise early, stand on deck arrayed in short cotton drawers, and bribe a sailor to draw buckets of water from the ocean to slosh over a body fevered by a night in a stuffy cabin and irritated by the attacks of militant and mephitic vermin.

True, those Spanish boats had bathrooms, because the ships had been constructed in Scotch or English shipyards. But unhappy days had fallen on those bathrooms; they were now used for storing vegetables.

The discomforts of travel, however, might readily be forgotten while studying the interesting passengers. Two Spanish Recolleto friars, tonsured and white-robed, were returning under American auspices to the little Visayan villages whence they had been driven by insurgents a year before—and very lucky to escape with their lives. What tales those priests told me and how their conversation was sandwiched with epithets about the Visayan natives, particularly about the insurgent leaders! Chungos (monkeys) was their habitual reference to that class of Filipinos.

There were fat Chinese mestizos (half-breeds), businessmen, and hacenderos of Panay and Negros, always discussing the price of sugar per picul or telling of haciendas ruined by outlaw raids.

A few American businessmen of the sutler type [one who sells provisions to roving troops] that follows an army and whose principal samples were brands of beer or whisky, held to themselves on deck or retired to their cabins to discuss their samples.

Half a dozen well-to-do Filipinos, some of them ex-insurgent officers, and politicians all, were returning from interviews with high officials of the new gobierno civil. They were voluble in their appreciation of the Constabulary that was to take the place of the army, which would resemble the old Guardia Civil of Spanish days, and would (so they hoped) rapidly suppress outlawry in their native provinces.

From the Filipinos I learned much of provincial conditions, of the causes of outlawry and cattle stealing, and of the means to take for their suppression.

Before the voyage was over, I had exhausted my small stock of Spanish, but had added many new words to my vocabulary. I began to realize that I was embarking on a strange life; and that only by a working knowledge of Spanish and the native dialects could I come to an understanding of the world around me and the problems of a Constabulary officer’s life.

At meals we gathered round a long table on the after-deck protected by double awnings from the sun; and there, cooled by the northeast monsoon and with a panoramic vista of palm-fringed islands slipping by, we ate the sopa de arroz (rice soup), the cocido (dish) of meat and vegetables, the biftek and pescado frito (fried fish), which made up the usual fare on inter-island craft.

The fish was always served after the meat course. All was washed down with a good grade of Spanish Rioja wine, and the meal finished with Edam cheese served in its red cannonballs, guava jelly in flat tins, bananas and other fruits, and coffee. To a hungry youth those meals more than atoned for the cockroaches in bed and the potatoes in the bath.

When the jolly Gallego captain was feeling particularly happy he would invite certain of the passengers to drink a cocktail, so called. An American bartender would have shuddered at the mixture which a Filipino major-domo placed in octagonal tumblers holding more than a half pint. It consisted of gin and water in equal parts, flavored by a liberal dash of Angostura bitters, with a tablespoonful of sugar and all beaten to a froth with an instrument that resembled a miniature broom.

But mighty good those cocktails were. The taste of them still lingers in my mouth, conjuring up the mixed crowd on the steamer, the warm smell of the southern sea, the dancing water of the narrow straits between islands verdure-clad from beaches of golden sand to rocky summits piercing the blue bowl of heaven.

All the “call of the East” seems sometimes held in those cocktails mixed on the old Pleguezelo and other ships on the waters of that fascinating eastern archipelago.

However, despite cockroaches and cocktails, forty-eight hours after leaving Manila we steamed between islets through the narrow straits that mark the entrance to Iloilo harbor. There I transferred to a diminutive steamer that plied between Iloilo on Panay Island and Silay on Negros Island. Soon I had opportunity to observe that comfort is always comparative; for the craft was no more than a top-heavy launch, laden to the gunwales with a mass of native passengers, chickens in baskets, dried fish in bales, guinamous, which is venerable fish in liquid state, in earthenware jars, live carabao and oxen, and merchandise of every description.

The variety of evil smells on that launch equaled the number of brands of pickles put up by a famous house. The old Pleguezelo was by comparison a holystoned yacht. For several hours I stifled in a crowd of Filipinos, Chinos, and mestizos, while, wobbling in the swell set up by a stiff northeast monsoon, we crossed the straits to Negros.

Soon the passengers became actively and enthusiastically seasick, giving me opportunity to make the interesting observation that a mestizo is always more violently nauseated than a pure-blooded native. The reason for this I cannot even surmise, but must leave to the explanations of trained ethnologists. It was indeed a pleasant little voyage.

Yet, but for the smells, the sickness of fellow passengers, and the combinations of both, indeed despite it all, I enjoyed the crossing. Air and sea sparkled under the cooling influence of the northerly winds which make the Philippine climate delightful for three or four months of the year.

We passed scores of white-winged lorchas (small schooners) and paraos (outrigger canoes), laden with sugar for Iloilo and leaping over the foaming combers. It was the season of the sugarcane harvest and long before we reached the Negros shore the smoke of haciendas rose against the green fields which sloped up toward the mountain jungles and crags.

At last we ran alongside a crazy bamboo wharf at Silay. Strong wharves are not built along the open coasts of Negros, because of the destructive typhoons; while a bamboo structure is as easily replaced as it is swept away.

Disembarking, I stumbled along the creaking, swaying pantalon (wharf) and hired a carromata with two horses for the drive along the coast road to Bacolod, the capital of the province of Negros Occidental, where I was to report to the senior inspector for duty.

It was the dry cool season which lasts from December to April or even May and the roads were soft with white dust that also lay heavy on the fields of sugarcane which bordered them. We drove beneath groves of coco palms or crossed shallow streams where carabao were cooling after the day’s toil in the cane fields, and at each crossing a ruined bridge testified to the wave of insurrection and disorder that had recently whelmed the province; although Negros suffered less from the insurrection and more from subsequent brigandage than any other island.

Negros is one of the wealthiest islands of the Philippine group, with rich volcanic soil. The World War so increased the price of sugar that many of the hacenderos must have made great fortunes.

I was astonished at the progressive appearance of the country, the substantial houses on the haciendas and in the village of Talisay through which we passed. When sugar was at five pesos the picul or more the hacenderos bought diamonds for their daughters or built fine houses of beautiful hardwoods, the mahogany of the islands, molave, ipil, and narra. When sugar dropped, they pawned the diamonds and mortgaged the houses.

A swollen orb sank blood-red behind the mountains of Panay beyond the straits, leaving its glory of gold and topaz to light the brief twilight of those latitudes. The air was heavy with the never-to-be-forgotten fragrance of sugar cooking from the vats of the hacienda mills.

––––––––