8,63 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Seren

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

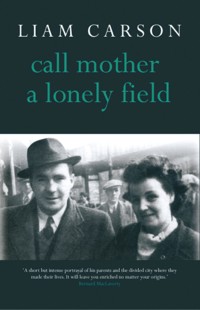

Shortlisted for the 2013 Ondaatje Prize, Call Mother a Lonely Field mines the emotional archaeology of family, home and language, the author's attempts to break their tethers, and the refuge he finds within them. Carson confronts the complex relationship between a son thinking in English, a father dreaming in Irish in a room just off the reality I knew', and a mother who, after raising five children through Irish, is no longer comfortable speaking it in the violent reality of 1970s Belfast. The author's Irish-speaking, West Belfast childhood is described through still-present echoes of the Second World War, dystopian science fiction, American comic books and punk rock. At the same time he explores how Irish language, literature and stories are transmitted from mouth to mouth. After years in London and Dublin, the deaths of his parents bring Liam Carson a new sense of community and understanding as he heals his fractured relationship with Irish. His rediscovery of the language as a sanctuary is central to a book exploring the potency of vanishing worlds, be they childhood, a city or a way of life. "A short but intense portrayal of his parents and the divided city where they made their lives. It will leave you enriched no matter your origins" - Bernard MacLaverty

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 151

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Praise for Call Mother a Lonely Field by Liam Carson

‘A tale from a dark and troubled place—Belfast in the ’70s and ’80s. Whatever light there is in the book comes from love and language. Liam Carson’s Call Mother a Lonely Field is a short but intense portrayal of his parents and the divided city where they made their lives. It will leave you enriched no matter your origins.’

—Bernard MacLaverty

‘Carson presents the sights, the sounds, the smells, the essential character of the Falls Road of the period… His mother’s descent into Alzheimer’s is described with a tenderness that is almost unbearable. Every mother should have a son like this—and indeed it is a lucky child who had parents like his. Liam Carson has done them both proud in this affectionate, haunting, highly readable and, at times, poetic memoir.’

—Maurice Hayes, Irish Independent

‘In this perfect gem of a memoir Liam Carson invites us into an Irish-speaking family home that was a bastion against the evils of imperialism, both cultural and material. Liam Óg’s story is one of setting out and return. For him, as for his father, Ithaca is not a place but a language. Like Hugo Hamilton’s The Speckled People, this memoir is a must-read.’

—Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill

‘A unique poetic meditation on an Irish-speaking family which draws fine threads between language and history and the life-saving properties of a wide-ranging selection of narratives, including family lore, folk songs, comic books and the heroics of mythology which underpin the Irish language. Liam Carson pours an astonishingly concentrated draught of wisdom into one slim volume.’

—Martina Evans

‘Like the city he grew up in, Liam Carson’s memoir of life in Belfast winds like a tangled web of streets, dreams, cultures and philosophies, where every page, pavement and street corner offer another dab of colour to a fascinating picture… His description of his mother’s Alzheimer’s disease and eventual death are blessed with clarity, gentleness and a heart-wrenching sadness. His memories of shared moments with his father are beautifully rendered… Carson’s greatest achievement is recycling a complex mix of emotions and ideas on language into a deeply moving read.’

—Michael Foley, The Sunday Times (Irish edition)

‘For such a tiny book, it is crammed with dozens of stories. Dreams are recounted, the plotlines of adventure books paraphrased and analysed, poems and song lyrics reprinted, folk stories and urban myths retold. This is a small book, and a hauntingly simple one. Call Mother a Lonely Field is an immensely pleasurable book, and a valuable addition to the canon of Irish autobiography.’

—Conor O’Callaghan, The Irish Times

call mother a lonely field

LIAM CARSON

for Niamh and Eithne

grá go deo

And like young Irishmen in English bars

The song of home betrays us

—Jackie Leven

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

1 TEARMANN

2 TAIBHSE

3 TEACH

4 TÍR NA N-ÓG

5 ALADDIN’S CAVE

6 TODAY IS DIFFERENT

7 BA MHAITH LIOM GABHÁIL ’NA BHAILE

8 CALL MOTHER A LONELY FIELD

9 TEARMANN

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

NOTES, SOURCES AND FURTHER READING

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Copyright

1

TEARMANN

sanctuary

My father would often tell me his dark dreams. In them, I am always a little boy, and we are lost in a forest. It is night, and we cannot see where we are going. I fall into quicksand, I am trapped, I am sinking. My Da frantically tries to rescue me. He stretches his hand to me, but cannot reach me. After his death, my own dark dreams came.

I see myself sitting on the Black Mountain, gazing down on the city. Immediately behind the Black Mountain rises the summit of Divis Mountain, whose name comes from the Irish dubh ais or black place. I look out to Belfast Lough and there is a massive swell building near Helen’s Bay. A huge wave rises, a wall of sea rising like a dragon from the depths, a tsunami that will drown the whole of Belfast. And although I am on the mountain, I can also see into the kitchen in Mooreland as if it is only a couple of feet away. My Ma and Da are sitting down to tea, oblivious to the catastrophe hurtling towards them. I run down the hillside, but I know it is too late, I know I cannot save them.

I find my dream echoed in an old scéal sí, or fairy tale, from Donegal, called Na Trí Thonnaí—the three waves. It tells of a man and his son out fishing on the open sea. It is a quiet, calm day. Then three large waves rise behind them as they head for land. The first is big, the second larger, and the third is so massive, they fear they are about to be drowned. The father asks his son to cast a knife ins an tuath. Into the tuath—a word that is difficult to translate. In Dinneen’s dictionary, it is defined as evoking the sinister: ‘wrongness, goety or negative magic’.

The son does his father’s bidding, hurling the knife into the heart of the demonic wave. Within the blink of an eye, the wave vanishes, and the men come safely to land. That night the son is visited by a man who tells him the knife is embedded in his daughter’s forehead—and that he must accompany him to remove the knife. He is taken to a fairy island and warned to refuse anything he is offered. He is brought to where the girl is stretched on a bed; he removes the knife, and she arises, safe and sound. The island people offer him all manner of things, but he refuses their gifts. The man tells the son he must forsake his native land. And so he does, heading for America, never to see his father again.

For my father, Liam Mac Carráin, Irish was a place of refuge. He was once interviewed for BBC Radio Ulster’s Tearmann—where guests were asked what gave them sanctuary in their lives. He chose the Irish language itself. He hid within and took comfort from words.

He arrived into this world as William Carson on 14 April 1916, only ten days before the Easter Rising. He spent his childhoodi dteach bheag i sráid bheag—in a little house in a little street, not far from Clonard Monastery, just off the Lower Falls Road. There was one room downstairs, two upstairs, and an outdoor toilet. His father, Davy Carson, was a fitter for Harland and Wolff—but he lost that job on 21 July 1920, when he was forced out of the shipyard in an anti-Catholic and anti-socialist pogrom.

A contemporary account tells of the fear on that day:

The gates were smashed down with sledges, the vests and shirts of those at work were torn open to see if the men were wearing any Catholic emblems, and woe betide the man who was. One man was set upon, thrown into the dock, had to swim the Musgrave channel and, having been pelted with rivets, had to swim two or three miles, to emerge in streams of blood and rush to the police officer in a nude state.

My grandfather was lucky to escape a beating or worse. In the next few days, seven Catholics and six Protestants were shot dead in the conflict that spread throughout the city. In the period between July 1920 and June 1922, over 20,000 Catholics were driven from their homes; 9,000 men were forced out of their jobs; and nearly 500 people were killed in sectarian attacks in Belfast.

Davy Carson never regained a full-time job. For years he struggled to make ends meet. He would get temporary jobs from time to time—obair chrua mhaslach, as my father described it—heavy, taxing work with a spade or pick in hand, often in the cruellest of weather. But as the 1920s drew to a close, and the depression of the 1930s loomed, the building work dried up. In 1928, he teamed up with some friends; they bought ladders, cloths and buckets, and set themselves up as window cleaners. It wasn’t easy to make a living at first. Most of the local women could only afford to pay a few pennies, and even the pennies were hard to come by, money was that tight for the people of the Falls. But soon he was cleaning windows for the local shopkeepers, for offices, and even the local police station.

One day the nun who ran the girls’ workhouse at the corner of Dunmore Street asked my grandfather to clean their windows. He was delighted—this was a large building with lots of windows, and he reckoned he’d get a decent payment, at least ten shillings. When he had the windows all spick-and-span, the nun asked him how many of a family he had. Five children, so a family of seven in total, he told her. The nun handed him a bag in which there were seven holy medals, seven scapulars and seven copies of the Agnus Dei.

‘Now,’ she said, opening the door for my grandfather, ‘there you go. A medal for each and every one of you. Thanks very much and God bless you.’

‘Reverend Sister,’ he replied, ‘I don’t want to be disrespectful to these holy things—but I’ve a wife and five children to feed. I don’t know any shopkeeper who’ll take these instead of money.’

The nun’s face reddened with shame. ‘Oh my, I’m so sorry, I didn’t think about that.’ She handed over a pound. ‘I hope that’s enough. Come back next month and every month after that.’

Davy Carson was also a great man for the music. He had a fine voice and knew a lot of traditional songs, although he only had the one in Irish—‘Fáinne Geal an Lae’ or ‘The Dawning of the Day’. As well as being a good singer, he could play the fiddle and the tin-whistle.

My great-grandfather was also called William Carson, and was a Protestant. He ‘turned’ Catholic when he married his second wife. Apparently, he was an Orangeman, and came from Ballymena. My father told us how his forebear had nine children with his first wife. After her death, he fell in love with a girl who worked for him. She consented to marry him, but on the condition he convert to Catholicism, and move to Belfast. There he had a further thirteen children: he fathered the equivalent of two soccer teams. He attended mass every morning, and the exposition of the Blessed Sacrament every afternoon.

We also know he was a cabinet maker, and my sister Caitlín still has his working bible—The Practical Cabinet Maker’s Design Book, by H. Thomson, published in Glasgow. The book has sections on every kind of furniture. Hall Furniture. Dining-Room Furniture. Library Furniture. Drawing-Room Furniture. Bed-Room furniture. There are different styles, Byzantine, Pompeian, Gothic. It contains designs for a perfect middle-class life.

Scattered throughout the book’s pages—and it is crumbling, the binding is gone—there are cabinet designs, cut from newspapers: intricate, delicate patterns, like paper dolls. Then there are newspaper clippings, poems, song lyrics. A few mention trams; one, ‘When’, speaks of death as a time where ‘the tramway track is finished, and the reign of mud is over’. Many of the poems are by Celtic Twilight amateurs. Some are political, one rails against ‘profiteers’, and lawyers and liars ‘making the same old useless laws’. In ‘Erin’s Brave’, a Mary Croft of Great Georges Street writes of heroes who ‘went forth in the morning of life’ to die for Ireland. There’s a news story from October 1891, ‘Visits to Mr Parnell’s Grave. A Tribute from James Stephens’. It describes how the crowds flocking to the grave are ‘by no means diminishing’, and how every day witnesses more and more floral tributes to the uncrowned King of Ireland. James Stephens, ‘the great revolutionary Chieftain’, founder of the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood, stands at the grave, his hat off, tears in his eyes. The report tells how Stephens lets go a loud sob, and a wave of weeping breaks through the crowd.

One page has one of my great-grandfather’s own designs, for a house altar; on the Tabernacle there is a Sacred Heart. At the end of the book, some newspaper poems and songs are pasted in, including a lullaby ‘The Slumber Town Express’.

At half-past six when the lights turn down

There’s a special train for Slumber Town

In my mind’s eye I imagine him at his doorway in the evenings, calling his children home. He ticks their names off on a roll, one by one. At night they all crowd into the house—or, actually, two little Belfast two-up-two-downs knocked into one. But it is all speculation. He died even before his last son, my grandfather, was born.

In his later years, my Da would often recall his father and there was hardly a day he wouldn’t think about him. He described him as the smartest man he ever knew. Not that he was particularly educated—the only schooling he had was from his time in Barrack Street Primary School, and from library books. But there was little he couldn’t turn his hand to. Quite apart from his skills as a fitter, he was a right jack of all trades—sewing, shoemaking, tailoring, painting, cooking. The family didn’t need to buy toys, my grandfather made them himself—toy boats, trains and trucks, wooden horses and the like for the boys; dolls, baskets and prams for the girls. Neither did the family have any need for a cobbler or a tailor: he mended the shoes himself, and made all the family’s clothes.

My father recalled that the older folk thought a child born after the death of its father had healing powers. My grandfather was said to have such powers. He had cures for whooping cough, thrush and other throat infections. In his youth, he practised his healing when asked, even though he didn’t actually believe in it himself. To ‘cure’ thrush, he would blow three times into the affected child’s mouth, invoking the Trinity. For whooping cough, a lock of his hair would be tied to the shirt of the sick person. He would comment, my father said, that he would sometimes be left nearly bald, and would never go out without his cap.

There were even superstitions and magic beliefs that lasted into my Da’s time. He wrote of the Belfast lamplighter, who would emerge at twilight to illuminate the city. He carried a long pole from which dangled a lit wick encased in a mesh. The Falls’ girls stood beneath the gas lamps with their dresses stretched out before them, believing they would be filled with gold. As soon as they looked down, the gold vanished like a will-o’-the-wisp.

If he lacked any real healing powers, my grandfather was a great man for stories, and therein lay his true magic. He would tell my Da stories of ghosts and of the fairy folk, of knights and of the great warriors of Irish mythology, Cú Chulainn and Fionn Mac Cumhaill. He wove tales about historical heroes he admired—Thomas Russell, Jemmy Hope and Wolfe Tone. He would take my Da and his brother Pat to McArt’s Fort on Cave Hill, and tell them how Tone founded the United Irishmen at the very spot where they stood.

They would have journeyed to Cave Hill by tram. For my Da, trams were always special. Meallacach is the word he used—beguiling, alluring, enchanting. He imagined that he must have first boarded a tram in his father’s arms when only a baby. He remembered being taken on tram trips from the age of about four. Up the stairs they would go, to the upper deck of one of the old red and cream trams that were common in Belfast. He loved hanging over the rail, the wind blowing in his face, his father holding him in a firm grip. Every weekend for years, my Da and Pat would join their father on journeys to the outskirts of the city—Greencastle, Dundonald, Castlereagh, the banks of the Lagan.

The trams were gradually phased out, replaced by electric trolleybuses. The tracks were pulled up from the tram routes, one by one, but the overhead cables remained. The trolleybuses would last until the 1960s, and I can remember them myself. My father hated them. He was still living in O’Neill Street when the trams were taken from the Falls. Eventually, all the trams vanished. When he boarded the last tram from Ardoyne Depot, his heart was broken.

My father was young when his father died suddenly. He had called on my Da to get up for work one morning. When my Da came back at the end of the day, his father was dead. He was distraught that he hadn’t had a chance to say goodbye, or to receive his father’s farewell blessing.

In later years he began to dream about his father. For over twenty years he had the same dream nearly every night. He is standing at the corner of Clonard Street and the Falls Road, waiting for a bus. Instead of a bus, there arrives a tram. He lights up with delight when he sees it. Just as he is about to board, the tram picks up speed, and disappears into a mist. No matter how many times he had the dream, he never managed to board the tram.

Why he should have this dream so often puzzled my father. For the life of him, he couldn’t figure it out. Finally he decided to visit a doctor friend who knew a bit about psychology. He told him of his childhood tram journeys. ‘The tram and your father are inextricably linked. That tram is an image or symbol of your father. You can’t get on that tram, and you never will, no matter how many times you have the dream.’

In 1930, at the age of fourteen, my Da started work as a post office motorcycle messenger, delivering telegrams to insurance brokers and shipping companies throughout the city. Each morning the messengers lined up before an inspector, who refused to let his men start their work unless the buttons on their uniforms were sparkling. He earned twelve shillings and seven pence a week. He followed in a family tradition—his grandfather and three uncles worked in the General Post Office. He would give his mother ten shillings, which paid for rent and coal. The remainder covered his expenses—a packet of ten Woodbine at two pence, a tram journey out of town for a penny.

In his book Is Cuimhin Liom an t-Am