Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

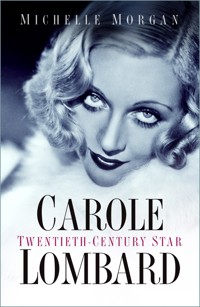

'An entertaining and lucid biography' - We Are Cult Carole Lombard was the very opposite of the typical 1930s starlet. A no-nonsense woman, she worked hard, took no prisoners and had a great passion for life. As a result, she became Hollywood's highest-paid star. From the outside, Carole's life was one of great glamour and fun, yet privately she endured much heartache. As a child, she was moved across the country, away from her beloved father. She then began a film career, only to have it cut short after a devastating car accident. After she picked herself back up, she was rocked by the accidental shooting of her lover; a failed marriage to actor William Powell; and the sorrow of infertility during her marriage to Hollywood's King, Clark Gable. Carole marched forward, determined to be positive – only for her life to be cut short in a plane crash so catastrophic that pieces of the aircraft are still buried in the mountain today. In Carole Lombard, bestselling author Michelle Morgan tells the story of a woman whose remarkable life and controversial death continues to enthral.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 420

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

This book is dedicated with much love and thanks to Vincent Paterno and Carole Sampeck.

First published 2016

This paperback edition published 2021

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Michelle Morgan, 2016, 2021

The right of Michelle Morgan to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 6939 0

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

1 The Hoosiers

2 Heading West

3 Up, Up and Away

4 Catastrophe

5 Looking Forward

6 Breakthrough

7 Mr and Mrs Powell

8 Rebellion

9 Divorcee

10 Sudden Heartbreak

11Hands Across the Table

12 The King and Queen of Hollywood

13My Man Godfrey

14Nothing Sacred Versus True Confession

15 Ma and Pa

16Made for Each Other

17 Mr and Mrs Gable

18Vigil in the Night

19 Real Life Versus Fairy Tale

20 The Last Hoorah

21 The Dark Mountain

Postscript

Sources

Select Bibliography

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I first decided to write a book about Carole Lombard nearly ten years ago. Since then, I have received many helpful emails and letters from all around the world. It is impossible to name everyone who has leant their support to this project, but please be assured that everyone who has provided inspiration, help, or both, is very much appreciated. Thank you all!

I would like to thank Christina Rice, who has helped me gain access to rare newspaper articles and stories. I don’t know what I’d do without her help.

Vincent Paterno, Carole Sampeck, Debbie Beno, Douglas Cohen, Bruce Calvert, Robert S. Birchard, Dina-Marie Kulzer and Ana Trifescu have all been gracious enough to share their photos, letters, rare documents and other memorabilia with me. Vincent also trawled the archives at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences – a kindness I will never forget.

I must also extend thanks to the following: Robert Matzen, Tegan Summer, Stan Taffel, Mary Curry, Karen Zuehlke, Jerry Tucker, Simon Elliott, Ted Okuda, Kay Shackleton, Albert Palacios, Valerie Yaros, David Stenn, Michael B. Druxman, the staff at the Kobal Archive, Jenny Romero, Michael McComb, Matt Vogel, Darrell Rooney, Jay Jacobson, Gregory Moore, Rick and Cora Brandt, Bruce Stier, James Reid, Brian Burton, Creager Smith, Jeffrey Sharpe, L. Thomas Horton, Carole Irene, Dixie Bradley and Evonne Quinn.

Thanks so much to my agent, Robert Smith, and to my editors, Juanita Hall and Mark Beynon, and everyone at The History Press for believing in the book.

I would like to thank my friends, Claire and Helen, for supporting my projects. Claire, I hope this book will join the others in your ‘Michelle shrine’!

Thank you to Mum, Dad, Paul, Wendy and Angelina for all the love you continue to give me on an everyday basis. I love you all very much! Finally, my husband Richard and my daughter Daisy … life would be very boring without you two. I love you both to the moon and back!

And to anyone I may have missed, sorry for the oversight, but thanks to you too!

I have never sacrificed myself for another. I am not a martyr. Being a martyr shows lack of courage. There are more lives ruined by so-called martyrdom than are saved. I do not believe in luck. You hear persons speak of his or her bad luck, but it isn’t luck they mean. It’s judgement – knowing how to take advantage of opportunities, grasping good ones when they present themselves, and rejecting the bad.

Carole Lombard, 1934

THE HOOSIERS

T hroughout her life, Carole Lombard would be reminded by her mother, Elizabeth Knight Peters, that she was the product of excellent breeding. The family was upstanding, she said, and the young woman must never forget that. Stories would be passed down about the men being hardworking entrepreneurs; high achievers in everything they did both personally and professionally. Elizabeth (aka Bessie) wasn’t just being overly proud of her relatives, she had good reason to share her tales, particularly on the part of her grandfather, James Cheney.

Cheney was known as the ‘wealthiest man in Fort Wayne’, with a fortune estimated at $2.5 million by the time of his death. That said, he was a very unassuming man who lived his life in such a quiet way that some of his friends had no idea what he had actually achieved in his lifetime. They knew he was rich, but for the most part he was known only as ‘Judge’ Cheney, the smartly dressed man who pottered around his garden, admiring the finely pruned hedges and nicely clipped lawn. He waved to passers-by as he raked leaves from the gravelled paths, enjoyed a joke, read the newspaper and always listened with a sensitive ear and words of encouragement.

Despite his unassuming nature, however, James Cheney was an extremely powerful man. Born to a good but relatively poor family, he read obsessively, began working by the age of 11 and continued until his death, over seventy years later. During his career he worked as a dry goods salesman, a builder’s supplier, a canal builder, tavern owner, land speculator, farmer, miller, Wall Street financier, stockholder and banker. As well as that, he also had an interest in the Western Union Telegraph Company and the Wabash Railroad, owned shares in several companies including the City National Bank of New York and Fort Wayne Gaslight Company, and became a prominent figure in plans to lay a cable across the Atlantic.

Cheney took great interest in politics, voted Democrat, loaned money to needy causes and frequently fought for justice. While never a member of any church, he donated generously to the First Presbyterian Church because his wife, Nancy, was a member and he wanted to support her interests as well as his own. A dedicated Mason, Cheney even helped out when plans to construct a temple hit blocks. He ensured the project not only got off the ground but took on a new life, too. When asked why he had decided to help, Cheney simply shrugged and said, ‘Well I’ve been a Mason for years but I never did anything much for Masonry, and I thought I had a chance now and would take it’. Such was the simplicity with which he undertook his projects. He may have been a multi-millionaire, but above all he was an honest, quiet and loyal man.

Carole Lombard’s grandmother, Alice, was the daughter of James and Nancy, and when she grew up she married Charles Knight. He was successful in a very similar way to James: at one time working as a manager at the Fort Wayne Gas Company and then the Fort Wayne Electric Company. He was also a prominent Mason, and for those reasons alone, he had a lot in common with his father-in-law. In fact, so well did the in-laws get along, that Cheney lived with Alice and Charles for the latter part of his life.

Carole’s grandfather on the other side of the family was John C. Peters, also a prominent businessman in Fort Wayne. He had started off as a cabinetmaker before going on to have an interest in various local enterprises and became president of the Horton Manufacturing Company (manufacturer of the Horton washing and ironing machines) and the Peters Hotel Company. His experience of carpentry was put to good use on several occasions. He oversaw the building of the Wayne Hotel in 1887 and also built two houses, one of which was said to be No. 704 Rockhill Street, the house where Carole Lombard was later born.

John C. Peters was described as thin and medium height, with white hair and a Vandyke beard. He and his wife, Mary, had a large family, including son Fred, the man who would go on to become Carole’s father. As he grew into a young man, Fred was thrilled to be given a job at the family firm, J.C. Peters and Company. Unfortunately, the experience almost cost the young man his life and would have disastrous results for his future happiness.

On the morning of 2 July 1898, Fred travelled to the shop on East Columbia Street, just as he did every day. He went up to the upper floor to take care of some chores and, once completed, decided to head back downstairs by taking the store’s elevator. Tragically, as he stepped in the carriage began to move unexpectedly and within seconds Fred found himself caught between the floor and the lift itself, causing him to be crushed about the head, shoulders, arms, chest, back and right thigh. The accident was horrendous and while Fred was freed quite quickly from the elevator, by that time he was barely conscious and in a terrible state.

Local doctors were called to the store and examined the young man. They ordered him to be moved to his home immediately, where they could examine him in private, away from the eyes of shop staff and customers. Fred was in great pain and distress, but after checking him over thoroughly, the doctors decided that while there were a great many bruises and lacerations, remarkably there were no broken bones and there would be no need for him to be taken to hospital. He was very lucky, they told Fred’s parents, but predicted that it would take several days before they would know the full extent of his injuries. It was impossible to rule out the possibility of internal injuries, though after confining him to bed doctors assured his parents that there was no reason why Fred could not make a permanent recovery. Mary and John were considerably relieved.

For the next six days Fred’s family fussed around and made him as comfortable as they possibly could. The local press sent reporters to the door, and on the 8 July reported that he remained confined to bed and was ‘still suffering much’. However, his mood was lightened somewhat after receiving many visitors. One friend, John Ross McCulloch, had been in hospital having his appendix removed when the accident happened. When he was well enough to leave, John refused to be taken home before he could visit – and cheer up – his friend.

Visits like these helped to spur Fred on to recovery, and he eventually returned to work. Then, on 1 July 1899, almost exactly one year to the day after the accident, the young man was rewarded with a promotion to what the newspapers described as ‘a very responsible position’. It was indeed – J.C. Peters & Company had been steadily growing over the years, with much of the success coming from the hard work of Fred Peters. His father John decided to reward him by handing over the day-to-day management of the hardware firm ‘as a reward of merit and close attention to business’. The Fort Wayne Sentinel wrote, ‘The promotion of Mr. Peters will be a source of much gratification to his hundreds of friends, many of whom will undoubtedly take advantage of the opportunity to call at the store and extend sincere congratulations.’

The announcement of the promotion gave great hope to Fred, but it was to last just six months, after which John C. Peters decided to sell the company to Henry Pfeiffer and Son so that he could devote more time to his manufacturing interests. By the time the new owners took charge on 2 January 1900 Fred had decided to leave and rumours went round town that he was about to take over the running of the Wayne Hotel. He did not, however, and instead went to work once again with his father, this time at the Horton Manufacturing Company. By 5 June 1901 he had taken over the prestigious job of secretary and treasurer.

As she grew up, Elizabeth Knight became terribly interested in playing and watching tennis matches. She was also something of a social butterfly, often attending parties and other gatherings with family and friends. Fred Peters was also a partygoer and enjoyed dances and picnics not only in town, but further afield too. He had known Elizabeth through his circle of friends for many years, but as the two grew into adulthood Fred began to see her in a different light. The two started dating in earnest, though their happiness threatened to come crashing down when it was discovered that Elizabeth was pregnant. It remains unrecorded as to what their families had to say about the matter (though one can imagine that it was not positive) and no time was wasted in trying desperately to hide the unfortunate situation. In late March it was announced in the local newspaper that the two were to be married, ‘Mr. and Mrs. C. Knight have issued invitations to the wedding of their daughter, Miss Elizabeth Jayne, to Fred C. Peters. The wedding will occur April 3rd at 8 pm at the home of the bride on Spy Run Avenue.’

Despite it being something of a shotgun affair, the bride’s home was a hive of activity during the week of the wedding. Alice Knight fluttered around making sure everything was just right for the upcoming ceremony, bridesmaids practised their bridal march and many friends came and went with good wishes and gifts for the happy couple. Parties and teas were held at various places in the lead up to the wedding, and the big day itself was something of a major event in the town. On that day, the parlour, dining room and living rooms were all lavishly decorated in green and white mignonette, Easter lilies and white tulips. Wild smilax, ferns and daffodils were used in the hall and stairway and in the dining room the tables were arranged in three sides of a square and decorated with sweet peas and maidenhair ferns. The room was romantically lit with candelabras bearing white candles with pink shades.

Elizabeth walked down the aisle in a beautiful gown of lace over white satin and trimmed with duchess lace and tulle, her hair styled beneath a veil fastened with an ostrich tip to match that of the six bridesmaids. After the ceremony, a lavish supper was held, and then the younger members of the family took themselves down to the Wayne Club, where they partied until Fred and his new wife made their excuses and left to prepare for their honeymoon.

The couple were away for two weeks before returning first to the Peters’ family home, and then to their new and permanent address of No. 704 Rockhill Street. Just over five months after their wedding, in September 1902, Elizabeth gave birth to their first child, Frederic (Fritz) Peters Jnr. Considering the couple were still young at the time, this new set of responsibilities could have been terribly difficult and hard going. However, for the most part, their social lives remained unaffected.

In February 1903 Fred was struck with a terrible bout of tonsillitis, but as soon as he recovered the couple continued their regular mix of events and parties. So affluent was their lifestyle that they even made the pages of the Fort Wayne Journal and Columbia City Post in September 1903, after travelling with friends to a party in a brand new car. ‘Their machine attracted considerable attention,’ said the Post, ‘It being one of the latest Wintons and complete in every sense.’

It wasn’t all glitz and glamour, however, as just a few months later on 13 December 1903 Elizabeth’s grandfather James Cheney passed away after a battle with cancer. The Fort Wayne Journal Gazette described the passing:

The millionaire, who was more widely known in Wall Street circles than in his home, passed away at 11 o’clock yesterday morning, after an illness of only three days. It could scarcely be called an illness, either, for there was no bodily ailment, but only a steady decline of the physical powers. The years had had their way with the mortal frame, the life ebbed away, and James Cheney, the friend and confidant of Jay Gould and Cyrus Field, the modest man who had been a chief factor in some of the greatest movements of modern times, passed from earth. Thus ended one of the strangest and one of the most notable careers in the commercial and social history of the west.

The family was devastated, especially as he had been a constant fixture in Elizabeth’s parents’ home during the last years of his life. It wasn’t the only negative thing to come their way, as not long after they had a break-in at their home on Rockhill Street, when a man by the name of Thomas Vachon entered the property and stole a great deal of food from their larder. The man was caught, though the matter was eventually dropped when the prosecuting witness could not give any intelligent testimony. Strangely the home would be targeted again several years later, when burglars gained entry through a cellar window and made off with a large amount of food and drink, including fruit, eggs, bread, coffee and wine. This time the burglars came prepared, and not only made use of a basket but also a wagon that acted as something of a getaway car.

Still, despite any disappointments that came their way during those first years of marriage, the social interests of Fred and Elizabeth carried on regardless. Fred became a regular fixture at the local golf club, where he not only played in various tournaments, but won many of them too. The accident that almost crippled him some years before had left Fred with blinding headaches at times, but it certainly did not stop him from taking part in his beloved sports activities and tournaments.

On 12 April 1905 the couple welcomed another son: John Stuart Peters (known by his middle name). Not long after, Elizabeth was spotted at several golf club parties and then visited friends and relatives in Chicago, Michigan and Ohio. She also became very interested in playing bridge, and her appearances at parties made the social diary of newspapers during the next year. Her interest in the card game knew no bounds and sometimes Elizabeth would even arrange charity games herself, with entry fees and proceeds from refreshments all going to good causes.

This skill for organising undoubtedly came from her mother, Alice, who consistently made sure that visiting relatives and friends had parties to go to and events to attend. However, Elizabeth’s skills went much further than social events, and over time she became involved with many different committees, but particularly the Young Women’s Society of the First Presbyterian Church. In February 1907 she became very vocal about her concerns for the nearby Hope Hospital and the various ways they needed help. Along with other members of the church, she organised a charity day which raised money for the hospital, and then afterwards kept a strict eye on what needed to be done in future.

In June 1907, Elizabeth was devastated to learn that her father, Charles, had been taken gravely ill while visiting his mining interests in Kentucky. Leaving the children with Fred she rushed to his side and, together with her brother Willard, managed to nurse the man back to health. In early July, Elizabeth and Willard returned to Fort Wayne with their father, who was described as ‘improving rapidly’.

Life got back to normal and continued with Elizabeth’s regular parties, weddings and theatre trips, while Fred went on hunting trips with his brother, William. His brother also featured in his golfing activities, and Fred beat him in the finals of the Benson Golf Club. ‘Fred Peters played a hard, steady and consistent game throughout,’ said the Fort Wayne Daily News. ‘He was unusually skilful at critical times and won the match on the merit of his work. He was effective in approaching and putting and was driving with accuracy and skill from the first hole to the last.’ Fred’s interest in golf did not end with just playing it, and before long he was involved with the pastimes committee at the local golf club too.

In early 1908, Elizabeth discovered she was pregnant again, though she continued with her social life in earnest. There seemed to be no stopping her, but on 6 October she was forced to slow down just a little when her daughter, Jane Alice Peters – the future Carole Lombard – was born at No. 704 Rockhill Street. ‘Mr. and Mrs. Fred Peters are rejoicing over the birth of a little daughter on Tuesday evening,’ said the Fort Wayne Journal Gazette on 8 October. The couple fell madly in love with the new child and she quickly became an important and beloved member of the family. Carole, however, didn’t ever see herself as particularly beautiful. ‘As a child, I not only was a blonde, but worse – a tow-head,’ she said. ‘I had a round face, wore my hair in a Dutch bob, and was fat.’

Jane fitted straight into her family’s social life, and her early childhood was a mix of family weddings, sports and community activities. At the very centre of it all was her mother, Elizabeth, who continued to organise events, win tennis matches and host meetings not only for the Young Women’s Society, but for the National Congress of Mothers and Parent Teachers Association too. Many of the meetings were held at the Peters’ house, where Elizabeth busied herself with refreshments and entertainment for guests. Jane would entertain the grown-ups by walking around on her tiptoes; a trick that convinced her mother that a dance career was in her future. Fred, meanwhile, won golf tournament after golf tournament while at the same time travelling around the country to oversee various business matters.

When Jane was 10 months old her grandfather, Charles Knight, passed away. His health had been up and down for a while and finally he died after a struggle with chronic Bright’s disease. Shortly after, the family went on holiday and then Elizabeth took her mother to Chicago to visit relatives.

The Peters family certainly did not want for anything. They had a servant to help out with general household chores and a washerwoman too. Holidays were spent at a family cottage in Rome City, and the local country club was like a second home. Every Christmas the family home was decorated specifically for the children and their grandmother Alice would arrange for her coachman, George Winburn, to deliver gifts of toys and popcorn. Winburn would also be in charge of driving the children to local parks during big family get-togethers at Alice Knight’s home.

Watching the way her mother and grandmother organised family functions and official events was inspiring to Jane and she quickly became a bubbly, confident child. Constantly told that girls could do anything boys could do, she made sure she was in constant competition with her two brothers and became involved in everything they did. Tree climbing, cops and robbers, sports: if it was something her brothers were into, the chances were Jane was too. Luckily, they loved her company and the three got along extremely well together.

In 1931, the Peters’ former maid gave a revealing interview to The New Movie Magazine. In it she described exactly how Jane spent the early years of her childhood:

Jane was always sticking up for her brothers, especially when youngsters would kid her by calling for ‘Fried Peas’ and ‘Stewed Peas’ meaning Fritz and Stuart, and then the racket would start. She had a little temper and this was developed by her continual contact with the neighbourhood boys, who were more numerous than girls then. Football, baseball, and racing were generally watched by Jane and before the games were over she always figured in the sports some way or other.

In early 1913, Fort Wayne was hit by an almighty flood that rendered many residents homeless. Easter functions were cancelled and those affected were forced to flee their homes and move in with friends and relatives. Spy Run Avenue, where Alice lived, was hit by the disaster and for a time she moved in with Elizabeth, Fred and the children. Luckily her home was not destroyed and she moved back fairly quickly, but many people were not so lucky and the flood ruined their properties and threatened the lives of their animals. Police were installed to stop residents returning to feed their pets, but this did not stop everyone. Children built rafts and tried to paddle along the streets, but soon found themselves stranded or, even worse, thrown into the water. The police labelled small boys as one of the biggest nuisances and newspapers begged children to stay away from the water.

The Peters family was not directly affected by the flood and Elizabeth used this miracle to help others. She opened her home to the public, called meetings with local women to share news of what was happening around town and invited workmen to come in and receive fresh clothing and warm drinks. She even arranged for coffee to be sent out to the men working on the flood waters, and made sure that everyone knew her home was a safe place to come. ‘She has relieved a great number of people in the last few days,’ said the Fort Wayne Journal Gazette, ‘and given a beautiful example, which as many of her friends as possible have tried to follow.’

Eventually the waters subsided and the town got back to some semblance of normality. Normal for the Peters family was seeing Fred head off on a four-week business trip to California, with Elizabeth and the children moving into Alice’s house while theirs was remodelled. On Fred’s return, the family went up to their Rome City cottage and then moved into the home of friends while the Rockhill premises continued to be revamped.

From the outside, things seemed perfectly normal for the family and Fred continued entering – and winning – golf tournaments. He also spent a great deal of time campaigning with neighbours to receive compensation after some of their properties had been bought up in order to widen the road. They won, and received various amounts of money on 11 August 1913.

Elizabeth, meanwhile, helped her mother prepare for a trip to Europe and took part in tennis tournaments with other family members. On 6 October 1913, Jane was given a party to celebrate her 5th birthday. Decorations were strewn all over the house in various shades of pink and white, friends came round to play and Elizabeth did everything she could to ensure the day was one to remember.

However, away from the hive of activity cracks were beginning to appear in the marriage. Fred’s injuries from his old accident still gave him cause for concern; the largest of which was the continuing violent headaches that almost paralysed him. By several accounts, these headaches caused his temper to flare, scaring Elizabeth and the children in the process. Jane very rarely mentioned her parents’ marriage during her lifetime, but did give a small insight when interviewed by Sonia Lee in 1934, ‘Contrary to the general notion, I haven’t had an easy time. I had a horrible childhood because my mother and father were dreadfully unhappy in their marriage. It left scars on my mind and on my heart.’

In newspapers published at the time there is no mention of the state of Fred’s health and he does seem to have kept up with his business trips, holidays to the cottage and golfing activities. However, telltale signs of trouble are demonstrated by the family spending more and more time apart. Sons Frederic and Stuart went to stay with friends in Michigan for some of their 1914 summer holiday, Elizabeth joined some of Fred’s siblings in a trip to Ann Arbor in October, and then Fred was seen with his brother instead of his wife at a dance club in December.

While he continued playing golf up to 1914, no mention of any games or tournaments can be found for Fred during 1915. Elizabeth’s calendar, however, could not have been busier. Incensed that there were no women on the school board, she and various other women trekked to the railroad crossings in Fort Wayne and collected some 800 signatures in support of their campaign to get some elected. She also found time to travel to Chicago and then entertain not only her children but their friends too. In late May she gathered up Jane, Frederic, Stuart and other little ones, and took them all to the Jefferson Theater for an afternoon of entertainment, then on to a café called Aurentz’s for refreshments.

Among her childhood activities, Jane had her first crush. ‘Let no-one say that a child cannot be in love,’ she told journalist Gladys Hall:

I mean, in love. No-one could tell me differently, because I was in love when I was eight years old. The very impossible; he was eleven, and he was named Ralph Pop. You may gauge the extent of my passion by the fact that at an age when the names Percival and Ronald and Curtis and so on were romantic names to me, I was able to idealize the name of Pop.

Despite writing letters, fighting off other suiters and stalking the young lad, Jane’s love was unrequited:

I tell you, I was in love with Ralph Pop, and even now, after all these years, I can’t really laugh at it, or about it. I felt all the pain, all the actual intense emotion, all the hurt pride and baffled hope of a woman for a man. Don’t ever laugh at a child in love. Really, don’t. It hurts.

Jane’s recollection of the romance is slightly cloudy. Records show that a Ralph Pop resided in Fort Wayne with his family, but he was the same age as Jane, not three years older, as she believed. Her love must have happened before she was 8, since shortly before her 7th birthday her mother put together plans that would see her, the children and her sister-in-law, Helen, leave Fort Wayne in early October 1915.

HEADING WEST

T he trip West was described in the local press as an extended holiday to California, and this certainly seemed to have been Elizabeth’s initial plan since she told her friends at the First Presbyterian Church that she would serve on the doll and infant booth at their Christmas sale in December. On 4 October 1915, the Fort Wayne Sentinel announced, ‘Mrs. Fred C. Peters and three children and Miss Helen Peters left Monday morning for Los Angeles, California, to remain for several months’. The next day the Fort Wayne Journal Gazette told readers that the Peters’ home would now be occupied by eight builders who were temporarily located in the city. Fred, meanwhile, moved in with his parents, John and Mary.

Carole herself spoke about the move in 1932, during an interview with the New England News, ‘Mother wanted to rest and there was no spot like California. We planned to stay for six months, but luckily the climate lived up to even more than mother anticipated and now we’re permanent fixtures.’

The family found themselves first in San Francisco but then very quickly headed south to Los Angeles, moving into an apartment on South Alvarado. No sooner had Elizabeth and the children settled in, however, than word came from England that her brother, Willard, had passed away. Elizabeth’s mother, Alice, did not know about the death until reporters came knocking at her door, and she was absolutely devastated. While family flocked to Fort Wayne to comfort her and organise the body to be returned to the United States, Elizabeth stayed firmly in Los Angeles.

By mid-March 1916, word came that her sister-in-law, Helen Peters, would be returning to Fort Wayne within the week, but Elizabeth and the children decided they would be staying until later in the spring. With her children starting school in Los Angeles, it soon became clear that the woman actually had very little intention of ever returning to Indiana. While she felt the climate was better for the health of her and her family, Elizabeth’s reason for staying permanently could have been Fred’s health rather than her own. There are several indications that he was suffering during this period. First of all, on his return to the country club’s tournament circuit, the once most formidable golf player lost his stride and was defeated in the Spring Championship. Then shortly afterwards he announced that he intended to quit golf for the next year, declaring that the rest would do him a lot of good. After that, instead of playing on the weekend as he normally did, he was seen watching his old pals from the sidelines. His attention then went into politics and he donated a whopping $500 to local Republican candidate Bob Hanna and became part of the advisory board for the campaign.

Settling into California did not mean that Elizabeth had any intention of getting a job. Instead, she relied on money sent from Fred for the care of his children and, at times, care packages from her mother, Alice. In April 1917, Fred travelled to California to see his family. If the purpose of the trip was to try and persuade them to return home, his pleas did not work. He was back in Fort Wayne by early May.

Shortly afterwards, his mind was on other affairs when the Horton Company premises went up in smoke after a machine caught fire. Two buildings were totally destroyed as a result. Fred’s father, John Peters, told reporters that he normally made an inspection of the plant after lunch, but on that particular day he had taken his wife out instead. ‘Of course it had to burn then,’ he said. ‘The plant was filled with new machines, machinery and materials and we were running night and day to keep up with our orders. The loss will reach about $150,000, with one fourth of it covered by insurance.’

Meanwhile in California, Elizabeth, Jane and her brothers continued to carve out a new life for themselves. Part of this was organising furniture from the Fort Wayne house to be shipped out to their new California home. When she wasn’t in school, Jane spent a lot of time with her siblings and continued to grow up as a tomboy. ‘Girls weren’t rough enough for me,’ she said. Although she was never particularly interested in playing house, in the rare moments when she did play with dolls the boys would laugh at her. Jane put them aside in favour of their toys instead. She would promise not to whine, cry or tell tales, and in return the brothers allowed her to join in with their favourite sports of baseball, tennis and golf. If she did begin to cry, however, the boys would leave her at home to stew; a punishment for being a ‘whiney little girl’.

Jane would often tear her dresses while climbing over fences or scrambling up trees. She would get into trouble for such misdemeanours but, more than anything, Elizabeth looked on in wonder at her little tomboy and never pushed her to become more ladylike. At school Jane joined various teams such as baseball, basketball and track, and always on the sidelines was Elizabeth, cheering the young girl on and supporting her when the inevitable injuries happened. She had a unique style of mothering, which Screenland magazine described as:

… just about 100 years ahead of her time. She does not believe in that sacred thing called parental rights. She is satisfied with the sincere friendship and love that her children offer her, and refuses to block with advice, tears or commands any course they care to follow.

As she did in Fort Wayne, Elizabeth busied herself with social events and parties and also became fascinated with numerology and the Baha’i faith; both introduced to her by a new friend.

The Peters family celebrated special days at the beach with their friends, and Jane also helped raise money for charity. On 13 July 1918, the 9-year-old served on Miss Morgan’s chocolate booth during a fundraising fete to help fatherless children in France. At another benefit the young girl met legendary actor Douglas Fairbanks. Jane was so in awe of the great man that she later described not being able to take her eyes off him. It did not take him long to spot that she was a big fan, and leant down to give her a small peck on the lips. ‘My determination to be an actress came just one second after Douglas Fairbanks kissed me,’ she said.

In Fort Wayne, Fred reached the realisation that his marriage had ended. Any efforts he made to convince his wife to come home stopped, but he still kept in touch with his mother-in-law, Alice, and even attended a party at her home in June 1919. Aside from that, he tried to carve out a normal life in Fort Wayne, attending social events at the country club, playing golf, working at Horton and even attending gymnastic classes.

In California, the family moved around quite a lot. In the 1918 Los Angeles Directory they are listed as living at No. 626 South Catalina, but by 1920 they had moved to No. 605 South Harvard Boulevard. It was likely, while at this house, that the youngster got her first movie role, opposite actor Monte Blue in A Perfect Crime. According to Carole, a neighbour saw the 12-year-old in the garden and actually recommended her for the part. ‘My mother rejoiced with me,’ she said, ‘and I had a glorious time for a few weeks.’

Her role in A Perfect Crime was brief; she was only on screen for a few scenes and no other roles came of the exposure. Carole was disappointed, but returned to school having been given a taste of what life could be like if she ever became a professional actress. The youngster continued her academic studies into high school, making friends with girls such as Sally Eilers, and renewing an earlier friendship with a young woman called Dixie Pantages. The family had also moved again. The Los Angeles Street Directory places them on El Centro Avenue at this time, but the 1923 edition has them at No. 154 South Manhattan Place.

Jane was growing up fast and she fell in love with a local boy. She recalled the experience in an interview with Gladys Hall in 1933:

When I was in my teens, I was so crazy about a boy called Clive that I could think of nothing but making opportunities to be alone with him. I didn’t care about anything but being alone with him, because all I wanted from him were his kisses, his love-making. I didn’t want to talk to him. I had nothing to say to him and he had nothing to say to me, nothing I was interested in hearing. We hadn’t one taste in common. We didn’t think alike. I didn’t want to do things with him, go places, or play games, or read books or anything like that. The whole point was that I loved him, but I did not like him. If the quality of emotion had been subtracted from the little affair, there would have been nothing left.

The girl was becoming more feminine in her approach to life; brought on, it would seem, through a fascination with the actress Gloria Swanson. Jane loved her films and looks so much that she went to extreme measures to try and look like her idol:

I so much admired her turned-up nose that I spent hours pushing my own inconsequential nose up, trying to make it look cute like Gloria’s. I thought her smile was so charming that I made myself look like a gargoyle going around showing my teeth as Gloria does.

Finally, the young girl caught a glimpse of what she looked like during her imitation. She stopped the game immediately. ‘Instead of making myself look like Gloria, I was completely spoiling what little beauty I did possess,’ she said in 1934.

At school, Jane took an interest in acting and was featured in several amateur productions. During one show she played the part of an old woman with a daughter. The girl who played her child was actually older than Jane, but that didn’t seem to bother the organisers. Another time she played a villain with a large moustache. The student thought the stick-on facial hair was so massive that if someone had stuck a brake to her shoulder she could have made a very lifelike bicycle. Another part was as the May Queen, complete with royal regalia. Her siblings thought the whole thing was a gigantic hoot. ‘My brothers kidded me to death,’ she said, ‘but I didn’t mind too much. They let me wear a grand taffeta period gown and a tiara, and that was compensation for the razzing.’

Having got a taste for films, Jane began to take acting classes and went on auditions, one of which brought her face to face with Charlie Chaplin. He was impressed enough to give her two tests for a new film he was preparing called Gold Rush. She did not get the part but enjoyed the experience. Another time, it looked as though she might be signed by the Vitagraph Company, but that also came to nothing. Then Jane met famed director Cecil B. DeMille. The man was impressed by her photogenic qualities and interested in the tales her mother told him about already having theatrical training. Still, DeMille thought she looked a little young to be brought to screen on a full-time basis. ‘My dear child,’ he said, ‘go back to school and see me in five or six years.’

In spite of any advice, Jane left high school as soon as she was able. Her education was not over, however, and she delved into acting classes, studying as much as she could. The young woman continued to go on auditions and was seen frequently on the Los Angeles club scene and particularly at the Cocoanut Grove, located in the Ambassador Hotel. Opened on 1 January 1921, the hotel was a mecca not only for tourists but the glamorous and seemingly sophisticated Hollywood crowd, too. Set in 27 acres of gardens, it had everything a visitor could want and a lot more besides.

It was not the pool or beautiful rooms that Jane wanted to see, however. Instead she would head straight for the in-house nightclub, where she would dance the night away with her friends. She was just 16 years old and yet, with her sophisticated look and fearless exterior, Jane seemed at least ten years older. Often dressed in black satin, the girl would wow the other Cocoanut Grove patrons by dancing up a storm and winning trophies in the regular competitions. Jane was proud to have won, but on many occasions she’d head back to the hotel the next day, trophies in hand, and sweet-talk the management into taking the prizes back and replacing them with cash. She did not care about parting with the trophies; she knew she’d win them back during the next competition.

In 1935 she said:

I went through the jazz-mad age with a vengeance, and spent almost every night dancing at the Cocoanut Grove. Dancing was all I thought of, and to be a superb dancer was the tops in my estimation. I’d have laughed at the idea of becoming a mere dramatic actress! It took me years to live down my reputation of being ‘the Charleston Kid’.

In later years she looked back on her time as a teenager with no affection at all:

I never want to be sixteen again. I think that eighteen is the dullest age in the world. If ever I was unhappy, it was when I was in my teens. That’s because you don’t understand anything when you’re that young. You’re puzzled and so you’re hurt. For only the things you don’t understand have the power to hurt you, like the power of darkness. With age there comes a richness that’s divine.

In spite of any unhappiness she may have felt inside, on the outside she was fearless. Because of this, it did not take long for Jane to be spotted at the Cocoanut Grove by various people who were anxious to further her career. Sometime during 1924 she was seen by members of a local dance troupe, the Denishawn Dancers, who had been booked to perform in the Cocoanut Grove. A touring company, they were due to leave for an eighteen month-long trip to India, Japan and China in 1925 and they were so fascinated by Jane that they actually asked her to accompany them. The adventurous young woman was excited to go, but her mother was not so keen and put a stop to the idea before it had chance to start.

UP, UP AND AWAY

W hile Jane was disappointed that she would be unable to dance her way across the Orient, she didn’t mope for long. She was soon to be discovered – though the way in which it happened is unclear. One of the official stories is that Jane was spotted at the Cocoanut Grove by a Fox talent scout, who invited her into the studio for a chat. This snippet of gossip was picked up by many columnists, including Edwin and Elza Schallert in their ‘Hollywood Highlights’ column for Picture-Play magazine. In the article the pair described how Jane was discovered by a film scout while on the dance floor at ‘fashionable and exclusive social gatherings’.

A different story was shared by the actress during an interview in 1932, when she described being at a dinner party and sitting next to a studio executive. He was impressed by her company and asked if she would like to be in the movies. She said yes immediately and a test was arranged. ‘I was dreadful,’ she remembered. ‘Even I knew that.’

Whatever her thoughts on the matter, the executives were impressed enough to sign the 16-year-old to Fox in early 1925. Jane was beside herself with excitement, but her mother was wary and wondered what was to become of her daughter’s future. It had been clear for a long time, however, that Jane was never going to be anxious to settle down, no matter what her age or profession. Elizabeth understood this and, given the circumstances of her own relationship with Fred, would never think of forcing her into a marriage she did not want.

Carole said:

Too many women have just one ambition during their twenties. They want marriage. Then they settle down and become housewives and let their own characters go. Marriage is important, naturally, but it shouldn’t submerge any woman’s personality. It should not wholly consume her life. I tried to keep the canvas broad. To forget the temporary problems of love and a career, and see the panorama of my whole life stretching out before me.

Jane’s name didn’t thrill the executives. They decided it needed to be changed immediately, and Elizabeth and a friend who studied numerology suggested the name Carole. Jane had tried this stage name before and was somewhat lukewarm about it. However, she did like it a lot more than her real name, which she described as ‘girly’ and she never believed that it suited her. ‘I was a tomboy of tomboys,’ she said.

Lombard was suggested as a surname (after a family friend) and the two names went together well. Her new name would be Carole Lombard, though for years studios, reporters and magazine writers would never know if it was supposed to be spelled Carol without an ‘e’ or Carole with. This resulted in the actress being credited both ways for some years, though to avoid any confusion it will be spelled Carole in this book.

Carole’s first real media mention came on 4 February 1925, when the Los Angeles Times featured a short piece entitled ‘Society Girl Goes into Silent Drama’. The article described how the ‘little miss’ had recently been signed to Fox after a successful screen test, and would soon be appearing in actor Edmund Lowe’s new movie. On 25 March her photograph appeared in the Los Angeles Times once more, this time in an article entitled ‘How do you like these Newcomers?’

Carole was happy to finally have a foot in the studio door. However, she was also acutely aware of the fact that making movies was vastly different to winning trophies at the Cocoanut Grove. Later, she admitted to reporter George Madden in an interview for Movie Mirror that she managed to get through the first few years:

Without knowing a thing about acting. I merely stood there in front of the camera and did what the director told me, and tried to keep my mind blank so I wouldn’t interfere with his thought transmission. Something seemed to give forth on the screen, but I never knew how it happened. It was all an accident.