5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

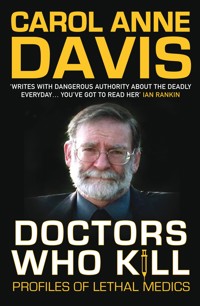

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Why would two young boys abduct, torture and kill a toddler? What makes a teenage girl plot with her classmates to kill her own father? Society regards children as harmless - but for some the age of innocence is shortlived, messy and ultimately murderous.Mary Bell, Robert Thompson and Jon Venables are infamous for their crimes against other children, but many of the less familiar studies here are equally as shocking. Thirteen murderers - the youngest only ten - used fire, poison, bullets and strangulation on victims from infants to pensioners. In a comprehensive study of juvenile homicide, Carol Anne Davis offers new psychological insights and a hard-hitting look at the role of society in an area too shocking to ignore.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 453

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Children Who Kill

Profiles of Pre-teen and Teenage Killers

CAROL ANNE DAVIS

ForIan

Contents

Acknowledgements

I’d like to thank Claire Rayner OBE for talking to me about the dangers of offering violence to children. Claire has published numerous books on medical issues and has been an energetic advocate of children’s rights throughout her life.

I also thank Ron Sagar MBE for answering my interview questions in depth and for providing unique details. As a Detective Superintendent, he interviewed Britain’s most prolific juvenile killer, Bruce Lee, at least twenty-eight times. With over thirty years experience in criminal investigation, Ron offered much insight into Bruce, a multiply-abused boy who claimed twenty-six lives.

I was similarly fortunate in interviewing Don Hale who fought for seven years to gain the freedom of the wrongly imprisoned Stephen Downing. Stephen was seventeen when he was jailed for a murder he didn’t commit – and was forty-four before his conviction was overturned and he was finally freed. As a result of his first class journalism on the case, Don Hale was made both Man Of The Year and Journalist Of The Year in 2000. I’m delighted that he took time out of his busy schedule to contribute to this book.

Thanks also to crime writer David Bell for drawing my attention to an interesting case I hadn’t heard of. David is author of the StaffordshireMurderCasebook,NottinghamshireMurderCasebook and LeicestershireMurderCasebook amongst others.

Most of my interviewees live in England, but my thanks extend overseas to Florida-based Lisa Dumond, a contributing editor to BlackGate and many other science fiction magazines. Though hard at work on her latest novel – and busily promoting her existing novel Darkers – Lisa helped me track down some vital criminal facts.

I’m also grateful to the organisations which answered my questions and sent me invaluable reports, namely The Children’s Society, Children Are Unbeatable, Save The Children, Kidscape and The Howard League For Penal Reform. Finally, my thanks to The Home Office for providing me with year by year statistics of children who kill.

Preface

As a child, I was friends with a twelve-year-old boy who attempted to murder a slightly older girl. They’d argued over which television programme to watch and he fetched a knife from the kitchen and thrust it deep into her back. Paul (not his real name) then left the room.

At first the girl thought that Paul had just punched her very hard. She felt ill and lay down on the settee on her stomach. When the pain intensified she looked back and saw the protruding handle of the knife.

The teenager staggered downstairs to alert a neighbour. Thankfully the neighbour left the weapon in situ – if she’d pulled it out, the girl would certainly have died. As it was, the blade had done irreversible damage to one of her lungs and she spent weeks in hospital, initially in intensive care. She later faced reconstructive surgery for the hole left in her back and had to take strong prescription drugs to help her sleep.

Twelve-year-old Paul now faced an attempted murder charge – but numerous adults came forward to say what a polite and helpful boy he was. He belonged to a youth organisation and they too were very impressed with him. The judge recommended that he see a psychiatrist and the parents said that they’d arrange this, but didn’t. His teenage victim was terrified that he’d attack her again.

It’s unclear how much the judge knew of Paul’s background – but I know that he and his siblings were regularly terrorised by their alcoholic father. He verbally mocked them and beat them with his belt. Paul’s mother did nothing to stop these sessions, instead adopting a slightly martyred tone and telling anyone who would listen that her children were very polite to strangers and that she couldn’t understand why they glared at her when they were at home.

In fairness, I really liked Paul’s parents and spent as much time as possible with them. Both had the capacity to be kind and generous to a child who wasn’t their own. Paul’s mother cooked me excellent meals and both parents took me with them on family outings, adventures I’d otherwise never have enjoyed. It was only in child-nurturing that they failed, presumably parenting as they had been parented.

Paul’s attempted murder charge was just one of numerous instances of violence in my childhood so it quickly faded from my consciousness. I rarely thought of it again until halfway through writing this book. Only then did I realise that Paul’s story had the same ingredients as almost every child’s story that you’ll find here. That is, the child is physically and emotionally abused by an adult or adults, often the very people that created him. In turn, he – or she – goes on to perpetrate violence on someone else.

The children in this book tortured, burnt, battered, strangled or raped their victims – victims aged from two years old to eighty. But these young killers had been tortured, burnt, battered, half strangled or raped before they carried out their pitiless acts.

The first two profiles are historic ones which demonstrate that children who kill aren’t a modern phenomenon brought about by horror videos or by single parent families. There are also brief details of other latter day killers in some of the sociological chapters, one of which bears a striking resemblance to the Robert Thompson and Jon Venables case.

The rest of the profiles are contemporary, featuring young killers from Britain and America whose ages range from ten to seventeen. But there are case studies in the later chapters involving younger children including a boy who killed at the age of three.

Several of the murders involve a sexual element, but as many readers find it difficult to understand how young children can become sexual predators, I’ve incorporated a chapter on youthful sex killers which offers many more case studies. These killers are male but some were sexually molested by their mothers so the chapter also looks at female sex offending, an under-reported crime.

These crimes are horrifying but comparatively rare. Though the media likes to suggest otherwise, there isn’t an epidemic of mini-murderers in Britain. To give some examples, in 1995 – 1996 there were 30 people under the age of eighteen convicted of murder in England and Wales. In 1996 – 1997 there were 19 and in 1997 – 1998 there were 13 such deaths. 1998 – 1999 saw 25 and the following year there were 23. These later numbers may rise as some cases are still being dealt with by the police and by the courts.

The numbers rise by approximately twenty convictions per year if we add manslaughter and infanticide to the murder statistics. But children are still far more sinned against than sinning when you consider that one child a week dies in Britain at its parent’s hands.

Moreover, the children who commit violent crimes have invariably been victimised by violent adults. A recent study of 200 serious juvenile offenders found that over 90% of them had suffered childhood trauma. 74% of the total sample had been physically, sexually and/or emotionally abused and over 30% had lost a significant person in their life to whom they were emotionally attached.

The following profiles, then, are stories of cruelty and of loss, of children who weren’t allowed to experience a happy childhood. But they can also be stories of hope because the power to change future childhoods is within our grasp.

1 The Hurting

Jesse Harding Pomeroy

Jesse was born to Ruth and Thomas Pomeroy on 29th November 1859. The couple already had a four-year-old son called Charles. They lived in a dilapidated rented house in Boston, USA.

The Pomeroys were an impoverished and argumentative couple from the start. Thomas was an angry, heavy-drinking man who hated his work at the local shipyard. Ruth was more industrious but equally morose, an intelligent women who was worn down by life.

She was also worn down with caring for Jesse as he was a physically weak infant who suffered numerous ailments. A serious illness in his first year left one of his eyes milky white. This clouded-over eye gave the fretful baby a sinister cast.

Thomas said that he couldn’t stand the sight of his second son and frequently hit the toddler. In response, little Jesse had skin rashes and terrible headaches and insomnia. He also had lengthy nightmares when he did eventually sleep. Charles too was being regularly beaten by his father and took it out on Jesse, who lived in constant fear.

Mrs Pomeroy was equally badly treated by her increasingly alcoholic spouse. Determined not to be the sole victim, she sometimes lashed out at her unhappy sons. Abuse makes children physically tense and clumsy so Jesse walked increasingly awkwardly, his shoulders hunched.

Victim becomes victimiser

When a child is constantly hurt like this, he naturally wants revenge but there was no way that Jesse could stand up to his enraged, belt-wielding father. So he turned to victims that couldn’t fight back. When he was five years old he caught a neighbourhood kitten and stabbed it with a small knife, enjoying its agonised cries. By the time that a neighbour intervened the animal was bleeding badly and Jesse had apparently gone into a trance. Later Ruth Pomeroy brought home a pair of pet birds to add colour to the household but Jesse waited till she’d gone out then killed them by twisting their necks. He was showing one of the traits of the fledgling serial killer – cruelty to animals. (The other signs include bedwetting into puberty and starting fires.)

When Jesse was six, his father changed employment and became a porter at the local meat market. He now carried carcasses around by day and beat his sons at night.

At school the other little boys played football whilst the increasingly-hunched Jesse sat and watched, nursing his most recent bruises. He fared little better in the classroom as he constantly lapsed into daydreams and the teacher caned him for this. We now know that excessive daydreaming is one of the symptoms an abused child displays in a desperate attempt to escape the painful reality of their lives – but many teachers of the mid nineteenth century believed that children were mischief makers who had to be broken down.

Finding that school offered him no more understanding than his home, Jesse started to play truant, going for long walks by himself or sitting reading novels. He bought some of them with dimes stolen from his mother’s purse. His father beat him for this and for playing truant, using a horsewhip on the child’s naked back.

Jesse ran away from home to escape further pain but was found by his father each time and punished. There was a strong humiliation element to these sessions, with Thomas Pomeroy making Jesse strip before taking him out to the woodshed and hitting him until he bled.

The fantasy phase

Desperate to be the victimiser rather than the victim, Jesse kept searching for small animals to mutilate. But it wasn’t enough and he began to fantasise about hurting a human, someone he could verbally taunt during the abuse just as his father always taunted him. He therefore joined in a game in the schoolyard where cowboys were tortured by Indians. Jesse insisted on being one of the torturers and became so elated that his playmates regarded him with distaste. He couldn’t forge any camaraderie with these boys excepting the torture games so remained apart from them, lost in his own lonely world.

When he was ten, his mother left his father as she couldn’t stand to see Jesse suffer any more abuse. But by then the damage had been done, and Jesse’s sadism was firmly rooted. He looked for sadistic scenes in novels and in boyhood conversations and eagerly thought about the day when a helpless victim would be his to extensively hurt and verbally torment.

Charles was constantly battering Jesse and though Jesse now fought back, he was still on the losing end of these vicious encounters. He needed a smaller boy that he could control.

The first torture victim

On Boxing Day 1871 Jesse seized his chance. He was now twelve and tall for his age. He found a three-year-old boy called Billy Paine playing unattended and made up a story to get the toddler to follow him. He led Billy into a disused building. Now he could make his sadistic fantasies a reality.

Jesse undressed the uncomprehending child then tied him to a roof beam by his wrists. By now the child was terrified – exactly the response that the boy torturer wanted. He beat the boy’s back with a stick again and again. Jesse himself had often been punished in this way by his brutal father but now he was the one in charge and he was going to make the most of it. It’s likely that the sadism continued until Jesse orgasmed but this is conjecture as Billy was too young to explain.

Eventually Jesse ran off, leaving the child swinging from the roof beams. A passer-by heard his semi-conscious whimpers, investigated, and cut him free. The three-year-old was too traumatised to explain exactly what had happened to him or to fully describe his captor so Jesse remained at liberty to torture again.

The second torture victim

Two months later, on 21st February 1872, Jesse met up with a seven-year-old boy called Tracy Hayden and took him to an abandoned outhouse. There he undressed the younger child and gagged him with a handkerchief. Jesse was already learning from experience, having feared discovery when Billy shrieked during his beating. This time he would only hear his captive’s muffled groans.

Jesse tied the seven-year-old’s feet together before roping his hands to an overhead beam. He thrashed the boy with a stick just as he had with his previous victim. But this time the violence was even more extreme and Jesse reigned blows upon the child that blackened his eyes and knocked out some of his teeth. He swore and laughed as he attacked his tightly-bound victim and was clearly overwhelmed by a sadistic glee. He also added a particularly terrifying verbal threat, saying that he was about to emasculate the helpless child.

Tracy was found by passers-by and taken to his parents who immediately called the police. The child was able to give them a reasonable description of the ‘big boy’ who had harmed him, but unfortunately this did not include the fact that his attacker had a clouded-over eye.

The third torture victim

Three months later the bloodlust had rekindled in Jesse and he struck again, asking an eight-year-old boy called Robert Maier if he would like to accompany him to the circus. Instead he led the child to a pond and attempted to drown him but the terrified victim managed to struggle free. Jesse then partially knocked the boy out and dragged him to an outhouse where he undressed him and tied him to a post. He whipped the boy with a stick, forcing him to use sexual (and, for the time, shocking) words like prick. Jesse masturbated during this taunting and quickly orgasmed. This sexual release apparently drained him of all tension for he released the child, ordered him to dress then let him leave.

The fourth torture victim

Seven-year-old Johnny Balch was the next neighbourhood boy to be enticed to an abandoned outhouse by the boy torturer. It was July 1872, a mere two months since the last attack, yet Jesse’s sadistic frenzy had increased so much that he actually tore off the boy’s clothes rather than unbuttoning them. Then he hung him by his wrists from a beam and flogged him with his belt. The abuse was the most ferocious so far, the belt lashing into every part of the helpless child’s anatomy. Again, it was Jesse’s orgasm that ended the assault. Thereafter he untied the brutalised boy and hurried away. The traumatised Johnny lay on the floor of the building for hours until he was discovered by a horrified stranger. A week after this assault, Ruth moved Jesse and Charles to a different part of Boston which offered cheaper rents.

The fifth torture victim

Within days of arriving in his new South Boston home, Jesse went out hunting for prey. On 17th August 1872 he found seven-year-old George Pratt near the beach. Jesse took him to a nearby boathouse where he stripped, gagged and bound him with a rope. As usual, he employed his favourite act of thrashing the child all over, only this time he used the buckle end of a belt. Jesse was becoming increasingly crazed during these assaults. He bit George’s face and one of his buttocks. This might have been a result of the atavistic urge that surfaces in some sexual sadists or it may have been learned behaviour, as some abusive parents bite their children as a punishment. Thomas Pomeroy might well have fallen on little Jesse in a drunken rage, battering and biting him in turn.

But even this sadistic biting didn’t satisfy Jesse’s increasing lust for blood. Now he produced a needle and stabbed the boy in the armpits and shoulders. Again, each act was accompanied by verbal taunting and Jesse clearly took great pleasure in telling the child what he was going to do to him next. His childhood experiences had turned him into a remorseless psychopath – yet he was still only twelve years old.

The sixth torture victim

A fortnight later memories of the previous attacks were no longer enough to sustain him and he struck again. This assault took place on Thursday 5th September, underneath a shadowy railroad bridge. Jesse led six-year-old Harry Austin there, stripped and battered him, the violence escalating by the second as Jesse produced a knife. He cut the screaming child in the back and under his armpits. Then, carrying out the threat he’d used on a previous victim, he tried to emasculate him. The hugely shocked child was found with cuts to his scrotum and numerous bruises. He was lucky to survive.

Jesse maintained an appearance of normality (or what passes for normality in such an isolated and unhappy boy) and his mother saw nothing different about him after these torture sessions. He continued to attend school and go to Sunday school and have interminable fights with his brother Charles.

The seventh torture victim

The next week, on Wednesday 11th September, Jesse struck up a conversation with seven-year-old Joseph Kennedy on the beach and lured him to a vacant outhouse. There he stripped and flogged the terrified child. Again the violence was increasing for he broke the little boy’s nose and dislodged several of his teeth. He laughed wildly as he produced his beloved penknife and slashed the younger boy on the face and thighs. Eventually he untied him, threw him into the salt marshes and ran away. It was clear to the police, and to the public who read about each new assault, that the torturer’s blood lust was escalating and that he’d soon kill if he wasn’t caught.

The eighth torture victim

And indeed, on Tuesday 17th September, the next victim almost lost his life. Five-year-old Robert Gould was led to a quiet stretch of the railway by the scheming Jesse. There the youth tore off Robert’s clothes and tied him to a pole. He slashed at the child’s head with his knife, alternately laughing and swearing. As the blood spurted, he showed a strange, frenzied joy. He held the knife in the air to watch the blood drip from it and was clearly transfixed at the sight.

Seeking yet further sadistic excess, he told the five-year-old that he was going to kill him and was about to cut his throat when railwaymen approached. Jesse ran away, doubtless congratulating himself that he’d once again evaded detection. He was wrong, for his victim had noticed that his torturer had a rare deformity – a milky eye.

Capture

There was only one boy in the locale with a milky eye – Jesse Pomeroy. He was arrested and every one of his tortured victims identified him. He admitted his crimes to the authorities, saying vaguely that ‘something’ had made him do it but within hours had retracted his confession and thereafter pleaded his innocence. He was sent to a reform school for boys, most of whom had been convicted of theft. They were terrified to find that the boy torturer now lived amongst them and they tried to keep out of his way.

Unfortunately the masters at the school flogged the children – and this obviously kept Jesse’s thoughts focused on such cruelties. He would seek out the punished victims and ask them how often they’d been caned and how it had felt. He would become visibly excited whilst hearing these details and undoubtedly used them as a masturbatory aid.

Ruth Pomeroy possibly knew that she’d failed her youngest child by letting him be beaten for so long by his father. Whatever her motivation, she kept petitioning the reform school to free him, suggesting that he was innocent of the crimes.

The school was impressed by her loyalty and her hardworking nature – and by the fact that Jesse was a model prisoner who did exactly as he was told. Nowadays we know that organised offenders such as Jesse are often model prisoners, being bright enough to work the system for their own ends. But this was an unsophisticated era and they assumed that Jesse’s good behaviour in an enclosed environment meant that he wouldn’t reoffend in the outside world. As a result, he was released to his mother in March 1874 after serving only seventeen months.

The first murder

Fourteen-year-old Jesse now returned home. His mother had opened a small dressmaking shop and his brother Charles was selling newspapers from a street stall. Jesse was immediately employed by both. Outwardly he appeared industrious and helpful – but inwardly he harboured the exact same sadism as before.

A week after his release, he opened up his mother’s shop in the early morning. A ten-year-old girl called Katie Curran came in to make a purchase and Jesse told her that she’d find what she wanted downstairs. Partway there, the girl realised that she was heading towards a dark cellar – but before she could retrace her steps, Jesse grabbed her from behind and hacked at her neck with his knife.

He carried the child down the rest of the stairs and cut her clothing away from her bleeding body. Then he proceeded to stab her numerous times and mutilate her genitals. Jesse concealed the little corpse in the cellar and returned to serving in the shop.

It seems that this was a crime of opportunity rather than design, for on previous attacks he’d brought his torture kit with him – namely rope for binding the victim, a handkerchief to employ as a gag and a stick or belt to carry out the flagellation. This time the victim wasn’t tied or gagged and the only weapon employed was the knife he carried with him at all times.

The police believed that Katie had been kidnapped by a stranger passing through the area, so Jesse remained free to seek further victims. He asked other children to accompany him into the empty store, but was so eager to get them on their own that they took fright and ran away.

The second murder

Serial torturers and killers are incredibly single minded, so Jesse continued his search for vulnerable victims. Five weeks later he found four-year-old Horace Miller who had gone to the nearby bakery to buy himself a cake. Jesse made up a story and lured the little boy to the marshes. There he threw him to the wet ground, undressed him below the waist and brandished a knife. Little Horace put out his arms to defend himself and received cuts to both hands. The blood-crazed Jesse stabbed him again and again. The fourteen-year-old also cut his victim’s scrotum, knowing that no one was likely to hear his agonised screams. All of Jesse’s rage went into his knife-wielding arm as he lunged at the four-year-old for a final time, almost decapitating him.

Hearing or seeing other people on the horizon he raced off, taking his knife with him. Within minutes two marsh walkers found the newly-dead child.

When the constabulary saw that the victim was a young male who had been undressed, stabbed and partially castrated, they thought of a youth who had committed such crimes before – Jesse Pomeroy. They wondered if he’d escaped from his reform school and checked to find that he’d been released. The police immediately went to Jesse’s home and arrested him. He denied everything, despite his shoeprints being found in the wet mud beside the body and dried blood being found on his knife.

At the police station, Jesse continued to invent alibis until they took him to the mortuary and showed him Horace’s mutilated corpse. For the first time he lost his composure and staggered backwards, admitting that ‘something’ had made him kill the little boy. He was referring to the compulsion to hurt and kill that every serial killer has.

This compulsion is incredibly strong – but the killer still chooses to give in to it. As such, he should be found responsible for his actions. After all, he can control it, in that he doesn’t give in to the compulsion when there are witnesses around. Jesse took his victims to comparatively remote locations and brought along the means to restrain them and muffle their shrieks and pleading. He also made sure that he didn’t get their blood on his clothes.

Seeking scapegoats

Now that Jesse had been captured, the local people and the press looked for an explanation. They didn’t understand the significance of the violence he’d suffered at his father’s hands.

Instead they blamed Jesse’s sadism on the pulp fiction that he read, with its themes of sailors being brutalised by violent pirates or of Redskins torturing their prisoners. In reality, most of these novels had print runs of over sixty-thousand so if truly corrupting one would have expected them to produce sixty-thousand boy torturers – but there was only one.

Awaiting trial

Jesse read ferociously in jail whilst awaiting trial, though presumably the ostensibly-dangerous pulp novels weren’t on offer. He spent the rest of his time writing notes to the youth in the next cell, asking him about his school floggings and telling the boy that he couldn’t get thoughts of his own childhood beatings out of his head. He also wrote frequently to his mother and to his brother Charles.

His mother sold her dressmaking shop to a neighbour – and to everyone’s horror they found Katie Curran’s decaying corpse in the cellar. As usual, Jesse alternately admitted and denied having anything to do with the crime.

The trial

He remained in jail until 8th December 1874 when his trial began. Witness after witness described seeing him leading Horace away. Others had seen Katie entering Ruth Pomeroy’s little shop. Even Jesse’s own defence lawyer suggested that Jesse was often overpowered by the need to hurt. These were superstitious times so the defence added that Jesse might have been born with evil powers.

Harsh discipline was only mentioned when one of his teachers said that he sometimes whispered to other children in class and that she ‘had to’ cane him for this. No one made the connection between Jesse being victimised by his father and then going on to victimise other boys. Jesse himself admitted that his sole interest was in hurting young males. The murder of Katie Curran appears to have been one of sexual curiosity and ongoing blood lust rather than intense desire.

The trial took place over three days and the verdict was guilty of first degree murder. The sentence was life imprisonment. Ironically, the local paper suggested the crimes wouldn’t have happened if Jesse had received parental discipline.

Prison

In prison, Jesse was put into solitary confinement, living in a small cell with his meals pushed through a slot in the door. This was best for the other prisoners as he would undoubtedly have tortured them. But it was bad for his own mental health – isolated prisoners often go mad. He was to spent forty-one years in such enforced solitude, with the exception of visits from the prison clergy and, twice a month, from his mother.

His sanity did seem to crumble during these years as he made numerous wildly-improbable escape attempts, some of which suggested a death wish. On one occasion he used a makeshift tool to bore through his cell and cut into a gas pipe, hoping to blast his way to freedom. He was knocked unconscious by the blast but made a full recovery.

Jesse wrote simple rhymes for the prison magazine during those years. He continued to read everything that he could get his hands on. His mother brought him snacks – and he was pleased to receive them but showed no pleasure at seeing her. They often discussed the letters requesting his freedom that she was still writing to the governors.

It was said that during these years he paid other prisoners to catch rats for him, which he then skinned alive – but these tales are undoubtedly apocryphal. After all, he was kept apart from other prisoners for most of his life. Then, as now, other prisoners and guards would have sold stories to reporters who were hungry for sensational information about high profile criminals. Then, as now, they doubtless made wild stories up.

After forty-one years alone in his cell, Jesse was given leave to go to religious services and take exercise with the other prisoners. He used his infamy and his machismo to inspire respect in them – but they were unafraid as he was becoming physically weak. Twelve more years passed in this way and Jesse didn’t make any close friends.

A change of scene

By the 1920’s, humanitarian reformers began to suggest that Jesse be allowed to live out his final months in a less punitive setting. Eventually the governor agreed. At first, like a battery chicken, Jesse Pomeroy resisted this, saying that his entire life was his cell. But over time he clearly rethought the situation and agreed to be moved to Bridgewater, the prison’s mental hospital.

In the summer of 1929 he was finally transferred to Bridgewater, having spent more than fifty years in Charlestown prison. By then he was almost seventy and had muscle wastage through spending so many years cooped up in a tiny cell. He was also partially blind and increasingly lame.

He remained surly after his transfer to Bridgewater and none of the staff managed to create a rapport with him. Some said that they never saw him smile. He often threatened to make escape attempts but it was clear that, given his growing number of infirmities, he wouldn’t get very far. He continued to protest his innocence until his death – the result of a heart attack – on 29th September 1932 when he was almost seventy-three.

The rationale

Jesse Pomeroy committed the early tortures and later torture-murders out of an overwhelming sense of bloodlust. Like many people from highly abusive backgrounds, he’d made a strong connection between sexual satisfaction and extreme sadism. These desires would remain throughout his life.

Jesse’s strongest stimulus for years (though he’d hated such floggings at the time) had been as a victim of severe beatings accompanied by verbal taunting. Watching a boy writhe and squeal as he flogged him and threatened him was much more exciting than a lover’s caress.

Early criminologists suggested that Jesse’s crimes were merely acts of violence, that they weren’t sex crimes because the victims weren’t sexually assaulted or raped. This shows a misunderstanding of sexual sadism. In sadistic attacks, the orgasm isn’t triggered by sexual intercourse but by inflicting pain on someone else.

Indeed, many sadists avoid coitus. If penis-based activity does take place it is often forced sodomy followed by forced oral sex, both of which further demean or hurt the victim. But as a callow youth Jesse Pomeroy may not have been aware of these optional extras. He orgasmed during the flagellation or the stabbing attacks, after which his sadistic urge was spent.

Jesse’s attacks began at twelve, the age when his libido awoke. He was undoubtedly homosexual so chose males as his lust objects. He chose small boys rather than boys his own age as they were easier to lure away from safe locations. They were also easier to restrain and were soon completely in his increasingly murderous power.

2 Pale Shelter

William Newton Allnutt

The pre-teen killer profiled in the last chapter came from a violent American home – but several years earlier in Britain, William Newton Allnutt was born into a British household that was equally damaging.

William was born in 1835 to a farmer and his wife. He came into the world to find that he already had five siblings. His mother was deeply distressed at the time of his birth as she’d borne the brunt of her husband’s temper for many years. But she was used to raised voices and fists as her father had also been a violent and tyrannical man.

William was a low-weight baby who was often ill. Several of his brothers and sisters were also poorly. Nevertheless his mother went on to have another two children after his birth.

When William was eighteen months old he fell against a ploughshare and the resultant injury was so severe that the doctor warned there might be brain damage. No such mental change was noted during these pre-school years but the abused little boy understandably became an increasingly sad and sullen one.

His father had by now become an alcoholic who kept terrorising his wife and all eight of his children. As a result, William sleepwalked and had terrible nightmares. The household was religious so sometimes these nightmares were filled with religious imagery.

He was an intelligent and articulate child who did well in his schoolwork and achieved a high standard of literacy. But he showed the disturbed behaviour that children from violent households invariably show – everything from fighting to truancy – so his teachers were often upset with him.

When William was nine years old his father became so cruel that he was considered insane. Mrs Allnutt at last found the courage to leave him. She sent all eight children away to boarding school or to stay with friends. (Within a year of their separation, her husband had developed epilepsy and within three years, at the age of thirty-seven, he would die.)

From frying pan to fire

She now moved in with her father, Samuel Nelme, and his second wife who were both in their seventies. They had a palatial home in the Hackney district of London with its own grounds. Samuel had been a successful merchant in the city so the family were able to afford a live-in maid.

Unfortunately William’s ill health continued, and his boarding school decided to send him home. And so the small, pale boy came to live with his mother in his grandfather’s deeply religious and all-adult household. It was a cheerless life without his siblings or schoolfriends for company. Samuel Nelme had always been quick to anger – and this anger was now often directed at William when he got up to everyday boyish pranks.

The fantasy phase

In September 1847 William committed a more serious act, stealing ten sovereigns from his house. His grandfather thrashed him and lectured him endlessly about the importance of honesty.

By now William – like many beaten children – was fantasising about killing his tormentor. If his grandfather died he, William, would be safe for the very first time. The cause of the twelve-year-old’s nightmares would be over and he would be able to relax during the day with his mother. He would have a childhood at last.

William had been taught all his life that people should use violence to get their own way. After all, he’d regularly watched his father hit him, his mother and his siblings. And now he was living in a second household where the man of the house solved disputes with a weapon or with his fists.

Deciding to kill his grandfather, William somehow acquired a pistol. The next time they were walking in the garden he lagged behind and aimed the weapon at his grandfather’s head. The bullet missed and William immediately dropped the gun into the bushes. He blamed the incident on a passerby, though no such man could be found.

William continued to suffer at his grandfather’s hands. The old man found the twelve-year-old boy untruthful – but William was presumably afraid to tell the truth in case it led to further verbal or physical abuse.

Killing time

One day his grandfather struck him so hard that he went flying and hit his head on a table. The pain was terrible. Worse, his grandfather said that he would almost kill him next time. The underweight and undersized boy was no match for the well built adult and may well have feared for his life.

He watched the household’s rats being poisoned by arsenic and realised he could use this to get rid of his batterer. He added the white powder to the sugar bowl, knowing that his grandfather craved sweet foods.

Over the ensuing week, every adult in the household became increasingly ill, vomiting violently. Samuel Nelme was the worst affected as he added sugar to so many of his drinks and meals. For the next six days his stomach and bowels voided their contents over and over. The doctor who was summoned found him writhing in bed and suspected he was suffering from English cholera. Ironically, each time he felt slightly better his daughter would give him some sweetened gruel to tempt his appetite. After six days spent in increasing agony, he died.

Suspicion

An autopsy showed that Samuel Nelme had ingested arsenic on several occasions. The police were called in to question the family and his mother admitted that her son had asked her about how arsenic worked. More damningly, he’d told the maidservant that he thought his grandfather would die very soon.

William refused to admit that he’d put arsenic in the sugar so was initially arrested for stealing his grandfather’s watch. But whilst in Newgate Jail he was visited by a Chaplain who suggested he admit his guilt to save his soul.

The twelve-year-old then wrote a letter to his mother saying that he deserved to be ‘sent to Hell.’ The child clearly had no inkling that the violence he’d suffered for so many years had, in turn, made him violent. Instead he said that he wished he’d listened to his mother’s religious teachings and that ‘Satan got so much power’ over him that he’d killed the elderly man.

On 15th December 1847 he was tried before a jury at the Old Bailey. The counsel offered an insanity defence and four doctors testified that William’s head injuries and a hereditary taint had driven him to madness. His mother testified that the boy heard voices telling him to steal.

But the judge said that the child was sane and found him guilty of murder. At this, the twelve-year-old almost collapsed and the wardens had to hold him up. The judge sentenced him to death but the sentence was almost immediately lifted, after which William Allnutt disappears from the record books. He may have been transported or given life imprisonment as young prisoners were treated very harshly in those unenlightened times.

3 Substitute

Cheryl Pierson & Sean Pica

Cheryl was born on 14th May 1969 to Cathleen and James Pierson. The couple already had a three-year-old son called Jimmy. The family lived on Long Island, New York.

James was an electrician who worked hard to give his family a good standard of living. He said that no wife of his would ever work so Cathleen spent her time shopping and chatting to the neighbours. She also had most of the responsibility for Cheryl as James said he didn’t know what to say to little girls. A very macho man, he was happiest with his male friends or when taking his son to Little League.

He provided the family with a beautiful home and often bought them all expensive presents – but he was equally generous with his punches and slaps.

Tyrannical

James Pierson’s own father had been a very controlling man, and now James copied his parenting methods. Cheryl and Jimmy weren’t allowed to speak at meal-times and had to eat a little bit of everything on their plate in turn or he’d get enraged and slap them across the face. They also weren’t allowed to sip from their glasses until they’d finished the food. This control extended to every facet of their lives with the children being warned that they must keep their bedroom doors open at all times.

At six foot two and strongly built, James Pierson was often a frightening figure to his children and his wife – and they all had the bruises to prove it. But rather than removing the children from the home, Cathleen merely told them to try to keep out of their father’s way. Cathleen herself had frequently watched her mother beat her brother with a stick so she was used to violence in the home.

Cheryl grew up into a pretty, very feminine little girl who Cathleen loved to dress up in fairytale dresses with ribbons and bows. At school she was only an average student, but academia wasn’t particularly important as she wanted to be a hairdresser or a beautician when she grew up. She was good at school sports and was very pleased when her father attended her games.

When Cheryl was eight the couple had another daughter, JoAnn. Cathleen showed Cheryl how to care for the new baby and Cheryl revelled in this, acting like a little mother. She was already becoming the peacemaker of the family, a child old before her time who always tried to make things right.

The neighbours felt sorry for the little girl who was always being shouted at and slapped by her dad, so they often invited her and her equally bullied siblings over. One neighbour even dared to tackle James Pierson for the way he treated his offspring but James angrily told him to ‘fuck off’.

Cheryl’s mother becomes ill

When Cheryl was nine Cathleen suddenly became very ill. She was hospitalised for weeks and subjected to numerous tests. James was frantic. In his own way he really loved his wife – and very controlling individuals are often terrified of being left alone. He visited her in hospital every day and kept demanding that the doctors get quicker test results.

Eventually Cathleen was diagnosed as having kidney failure and sent home to await a transplant. She was so ill that she mainly slept on the living room couch, so James started going into the marital bedroom to watch TV. He called Cheryl in to lie on the bed next to him as televised sport was something they both enjoyed. They’d take in cans of soda and crisps and Cheryl would curl up with her head on his chest. Sometimes both father and daughter would fall asleep.

At other times he’d wrestle her playfully or tickle her or lift her over his head. Cheryl was pleased that at last her daddy wasn’t ignoring her. But she’d later claim that this touching became increasingly inappropriate.

Kidney transplants

Cheryl’s mother Cathleen remained ill for the next six years, apart from the periods following her first and then her second kidney transplant. When a relative asked her why her kidneys had declined so rapidly, she said it was because her husband was beating her. She also told a friend that she wanted to leave him because he was always shouting at the children and criticising them. Cheryl had by now matured into an attractive thirteen-year-old but she still had to act like a little child in the presence of her dad. Observers noted that James would call her over to him and make her hug him and act in a generally flirtatious or unduly deferential way.

Incest is suspected

Cathleen now told a neighbour that she wanted Cheryl out of the marital bedroom, that she thought her husband might be touching the thirteen-year-old. The neighbour suggested to Cheryl that she should watch TV in her own room. But when Cheryl did so her father turned mean and said ‘Am I not good enough to watch television with any more?’ He also picked fights with the increasingly nauseous and swollen Cathleen so Cheryl went back into the marital bedroom to keep the peace.

James became increasingly jealous of Cheryl, punching her in the mouth when he discovered that she’d written a boy at school a Valentine card. He also punched her in the face for putting a pretty sash around her waist to brighten up her school uniform. Unfortunately it’s quite usual for authoritarian parents to try to control a teenager’s sexuality in this way. He started listening in to her phone calls, just as he’d once listened in to her mother’s phone calls – and she often had to end phone conversations with female friends because her father wanted her to take a nap with him.

James is hurt

When Cheryl was fourteen, her father badly damaged his legs in a work-related fall and it was feared he’d never walk again. Cheryl now had to take care of him and Cathleen and be a surrogate mother to six-year-old JoAnn.

Frightened and in pain, James became even more difficult to live with and his need for control increased. He told his son Jimmy what type of haircut to get, what to wear and what occupation he should be following. Jimmy turned eighteen and left, vowing never to return. But he continued to see his dying mother, though both hid these meetings from his father. Cheryl also saw her brother occasionally and admitted that she missed him a lot.

I’ll be watching you

James now installed an elaborate security system so that he could see into every room and corridor of the bungalow. He also hid a gun – including one submachine gun – in every room.

Cheryl tried harder and harder to please her dad. Visitors to the house noted that he’d punch her and pull her hair in supposed play, but that his actions clearly hurt her. The abuse would end when Cheryl hugged him and said ‘Daddy, I love you.’ He’d then rub her chest or entwine his fingers through her hair. Various people saw Cheryl lying on top of her father – and one relative was perturbed to find them lying like this, fully dressed, under a sheet on the marital bed.

One of Cheryl’s schoolfriends told a school counsellor that she thought Cheryl was being abused by her dad – but the counsellor said that Cheryl would have to come and see her. Like all abused children, Cheryl would have feared both her father’s revenge and her own public humiliation, so she didn’t approach the counsellor. (At least a dozen adults strongly suspected that Cheryl was being abused by her father – but this young girl was the only one who had the courage to go to the authorities.)

Cheryl’s world remained very small. She wasn’t allowed to date or to wear nail varnish or make-up. If she went to see a film with a friend, her father would follow her and sit a few rows behind.

Stunted development

Unable to grow up, Cheryl remained immature. Friends noticed that she often looked frightened. Her father constantly warned her not to talk to boys at school – and if she went over to a friend’s house to get her hair cut, he would time her so that she didn’t stay out too long. Cheryl was virtually running the Pierson household but James still found fault with her and a visitor was shocked to hear him refer to his daughter as ‘a little cunt.’

Motherless

In February 1985 Cathleen finally died. Now Cheryl and JoAnn were left alone with their grieving father. Cheryl had to do all the cooking and cleaning every night when she came home from class though kindly neighbours sometimes helped by supplying the family with meals. But love at last entered her life when one of the boys at her school, Rob Cuccio, comforted her over the loss of her mum.

Rob Cuccio

Rob was the son of a retired detective and a bank clerkess. They were a religious family who taught catechism at church.

James Pierson was very unhappy at the prospect of Cheryl dating Rob. He made up lots of reasons why the young lovers shouldn’t see each other and finally insisted they sat in his lounge watching TV with him and JoAnn. After a while, Rob found this so awkward that he finished with Cheryl, but he missed her and started seeing her again.

One day as they prepared to eat ice cream, James told Cheryl to give each of them a napkin. Cheryl gave Rob a napkin then gave her father one – and her father was so enraged at being served second that he punched her in the face. Shocked and frightened, Rob walked out. It’s likely that Cheryl begged him not to say anything. She’d definitely begged other adults not to intervene after she’d been hit by her dad.

Wishing he was dead

Like numerous abused children, Cheryl had begun to fantasise about killing her dad. Mostly, such revenge fantasies remain just that. They give the abused person a sense of control over what’s happening which temporarily makes them feel better. The killing remains at a fantasy level, for the abuser is such a terrifying figure that the child doesn’t have the nerve to physically fight back.

Unfortunately, the talk at school turned to a local murder that had been carried out for cash. Cheryl wondered aloud why anyone would murder a stranger for a fee – and one of her classmates, Sean Pica, said that he would kill if the price was right.

Sean Pica

Sean was born on 18th February 1969 to Benjamin and JoAnn Pica in New York. His father was a policeman and his mother a nurse. The couple already had a two-year-old son called Joe. Three years after Sean was born they had a third son called Vincent and the family was complete. JoAnn took the boys to church every week and also taught catechism to a group of youngsters in her home.

The marriage was an increasingly unhappy one and when Sean was seven his father left. He came back within months when nine-year-old Joe was diagnosed with leukaemia. Joe recovered and counselling failed to resurrect the marriage so Benjamin left again. He and JoAnn were divorced in Sean’s tenth year.

Benjamin kept in touch with the children – and they got on well with his new wife – but JoAnn continued to constantly criticise him to her three sons. Sean found this very difficult as he still loved his dad.

In fairness, JoAnn had to work incredibly hard to support her brood. She sometimes spent all night giving private nursing care then went straight on to her daytime nursing job at the hospital. It too was demanding as she worked in Intensive Care.

Sean’s second father

The following year, Sean’s mother met a new man called Jim. Three months later she married him, saying that she felt guilty about having sex outside wedlock as her religion didn’t allow for this. She told Sean that Jim, a hospital laboratory technician, was really his father now.

At first Sean was happy to have this new father figure in his life. Jim took the boys to games and took an interest in their hobbies. They also enjoyed family barbecues.

But Jim changed when he was drunk. He beat JoAnn and threw the family’s beloved labrador against the wall. Sean definitely witnessed this violence – and may also have suffered it. People in his Boy Scouts group noticed that he was troubled, that he had something on his mind.

Three years into the marriage, Jim said he was going out to watch a softball game – but he never returned. JoAnn, who tended to make light of family problems, was very embarrassed by his desertion. She now criticised both Benjamin and Jim to young Sean.

Sean clearly wanted a father figure, and became close to one of the Scout leaders. He also became a surrogate father to a much younger mentally handicapped boy, helping him to earn his badges in the Scouts.

Sean entered his teens, a sensitive and gentle boy who was always willing to help others. He worried about his mother but still enjoyed spending time with his biological father. He excelled in carpentry.