14,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Prestel

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

This is the first book to tell the inspiring story of near tragedy and ultimate triumph behind the dazzling work of one of today's most respected and best-loved artists. Chuck Close is one of the most acclaimed American artists to emerge since Andy Warhol. His larger-than-life portraits look out from the walls of museums and galleries around the globe. His virtuosity and variety of technique, combined with the ambition and accessibility of his chosen subject matter the portrait re-invented on a heroic scale has made him a great favorite with the public and has won him the respect of his peers. Chuck Close has achieved fame, yet his full story has never been told until now. Author Christopher Finch has known Close since the late 1960s when the artist was creating his first masterpieces in an unheated SoHo loft. Finch chronicles Close's childhood battles with illness and dyslexia and his rise to the pinnacle of the art world. At the age of 48 he was struck down by an occluded spinal artery that left him a partial quadriplegic. With extraordinary determination, Close overcame this potentially career-ending disability, not only learning to paint again but producing work of extraordinary richness that equals or surpasses his previous achievements. With style and authority, Finch reveals the human reality behind Close's visually eloquent but eternally silent portraits.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

Chuck Close|Life

CHRISTOPHER FINCH

Prestel

MUNICH • LONDON • NEW YORK

Chuck Close working on Keith in his studio at 27 Greene Street, 1970. Photo by Wayne Hollingworth

Der Inhalt dieses E-Books ist urheberrechtlich geschützt und enthält technische Sicherungsmaßnahmen gegen unbefugte Nutzung. Die Entfernung dieser Sicherung sowie die Nutzung durch unbefugte Verarbeitung, Vervielfältigung, Verbreitung oder öffentliche Zugänglichmachung, insbesondere in elektronischer Form, ist untersagt und kann straf- und zivilrechtliche Sanktionen nach sich ziehen.

Sollte diese Publikation Links auf Webseiten Dritter enthalten, so übernehmen wir für deren Inhalte keine Haftung, da wir uns diese nicht zu eigen machen, sondern lediglich auf deren Stand zum Zeitpunkt der Erstveröffentlichung verweisen.

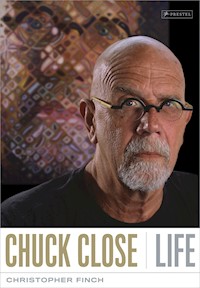

Cover: Chuck Close in front of Self-Portrait I, 2009.Oil on canvas, 72 x 60 in. (182.9 x 152.4 cm). Photo by Michael Marfione

© PRESTEL VERLAG, MUNICH · BERLIN · LONDON · NEW YORK, 2010

for the text, © by Christopher Finch, 2010for illustrations of works of art by Chuck Close, © by Chuck Close, 2010

All rights reserved. Electronic edition published 2012

Prestel, a member of Verlagsgruppe Random House GmbH

PRESTEL VERLAG

Neumarkter Strasse 28, 81673 MunichTel. +49 (0)89 4136-0 | Fax +49 (0)89 4136-2335

PRESTEL PUBLISHING LTD.

4 Bloomsbury Place, London WC1A 2QATel. +44 (0)20 7323-5004 | Fax +44 (0)20 7636-8004

PRESTEL PUBLISHING

900 Broadway, Suite 603, New York, NY 10003Tel. +1 212 995-2720 | Fax +1 212 995-2733www.prestel.com

Prestel books are available worldwide. Please contact your nearest bookseller or oneof the above addresses for information concerning your local distributor.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2009943596

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data: a catalogue record for this book is availablefrom the British Library. The Deutsche Bibliothek holds a record of this publication in theDeutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographical data can be found under:http://dnb.d-nb.de

Editorial direction by Christopher Lyon | Edited by Mindy WernerEditorial assistance by Ryan Newbanks | Proofreading and indexing by Ashley BenningDesign by Mark Melnick | Typography by Duke & Company, Devon, PennsylvaniaOrigination by Reproline Mediateam, Munich

ISBN 978-3-641-08341-0V002

Contents

Preface

Prologue

Part I

Chapter 1

Born on the Fifth of July

Chapter 2

Learning to be Unafraid

Chapter 3

Life Lessons

Chapter 4

Everett

Chapter 5

Breaking Away

Chapter 6

Bicoastal Adventures

Chapter 7

New Haven

Chapter 8

Transitions

Part II

Chapter 9

Rags and Rats

Chapter 10

Grand Unions

Chapter 11

Heads

Chapter 12

Recognition

Chapter 13

Downtown Domesticity

Chapter 14

The Grid Emerges

Chapter 15

Widening Horizons

Chapter 16

Family Matters

Chapter 17

Leaving SoHo

Chapter 18

Prismatic Grids

Part III

Chapter 19

The Event

Chapter 20

Alex II

Chapter 21

Regeneration

Chapter 22

Head-On

Chapter 23

Process and Pragmatism

Chapter 24

From the Oval Office to the Kremlin

Chapter 25

Inspiration Is for Amateurs

Chapter 26

Portraits of the Artist

Chapter 27

You Start Off with a Blank Canvas

Acknowledgments

Photo Credits

Preface

One day in late October 2004, I called Chuck Close from the steps of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where I had just attended the press view of an exhibition surveying the career of one of his predecessors, the early American portraitist Gilbert Stuart. The purpose of my call was to arrange for a studio visit, but in the course of the conversation Chuck proposed the idea of my writing a book about his career. When I pointed out that there were already several volumes dedicated to his work, he countered that they were either catalogues of single exhibitions or were limited to a specific area of his art, such as printmaking. What was yet to be done, he said, was a comprehensive book that covered his complete oeuvre in every medium.

One reason he thought of me as a logical candidate for this project was that I had been a witness to his career from its beginning. I had met Chuck and his wife Leslie in 1968 when I was an associate curator at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, and had been instrumental in the Walker purchasing his first major painting to enter a public collection—the now iconic Big Self-Portrait. When I settled in New York the following year, I became a frequent visitor to his SoHo loft, hung out in the same bars and restaurants, and on Saturdays we often toured the galleries together, logging innumerable hours of conversation and debate about art and everything else from politics to movies.

This was a dramatic period, full of cultural and social turmoil, during which SoHo was transformed from an urban wilderness colonized by painters, dancers, and musicians—who at first were little more than squatters—into one of the centers of the international art world. Chuck was at the nexus of that ferment, and I was a privileged eyewitness. I had ongoing access to his seminal photorealist paintings (a term he dislikes) as they were being committed to canvas and saw how he took a leadership role in the art world protests that followed the tragic shootings at Kent State. He was a witness at my wedding and a couple of years later painted a major portrait of my wife, Linda, which is now the pride of the Akron Museum of Art. I have been a close observer of his career ever since.

A day or two after that initial phone conversation, we discussed the idea of a book over lunch, and a few months later I had a detailed proposal for a monograph ready to submit to publishers. The most interesting response came from Christopher Lyon of Prestel Publishing, suggesting not one but two books, the first the comprehensive study of his art that Chuck had envisioned, to be followed by a full-scale biography. Unlike almost any other major living artist, the dramatic arc of Chuck’s life justified such a concept, not only because his work has been interwoven with his life in an unusually rich way, but because at the center of both is a traumatic event that would have destroyed most careers and which Close overcame with a determination and flourish that can only be described as inspirational. This momentous episode would, of course, have to be addressed in both books, but only in an exhaustive biography could it and other key aspects of his story be treated as fully as they deserved to be. A degree of overlap between the books would be inevitable, since to some extent the biography draws upon research and quotes used in the first book, Chuck Close: Work (published in 2007). Chuck Close: Life,however, stands by itself as a book that is complementary to the earlier volume but far more complete with regard to biographical material.

When embarking on the biography, I was encouraged by the knowledge that Chuck Close is a pack rat, one of those people who holds on to the ephemera of his past—childhood snapshots, elementary school report cards, high school yearbooks, even his grandmother’s old magnifying glass—all preserved as meticulously as the catalogues and reviews that form a record of his adult career: a biographer’s dream. Before I started work on either book, he handed me a typewritten family history compiled by his Great Aunt Bina, forty-five single-spaced pages packed with invaluable information about everything from his family’s migration from Nebraska to the Pacific Northwest to the circumstances surrounding Chuck’s birth. I included a few tidbits in Chuck Close: Work and then put her typescript aside to draw upon at length for this biography.

As I embarked on Chuck Close: Life, its subject produced other treasures, such as his baby album—scrupulously and tellingly annotated by his mother—as well as access to some of his oldest friends whose generously shared reminiscences facilitated my reconstruction of Chuck’s life in Everett, Washington, in the 1950s. In addition to all these resources, Chuck made himself available for innumerable hours of questioning, patiently going over the details of traumatic events in his past as well as the complexities of his relationship with his mother, a difficult woman who was in crucial ways responsible for much of who he is today. All this enabled me to reconstruct his early years in great detail, so that whereas his life prior to settling in New York occupied a single chapter of Work, it takes up eight chapters of Life,tracking the evolution of Chuck Close the artist as he advanced, sometimes painfully, from the Everett Public School System, through Everett Junior College and the University of Washington, and finally on to Yale, where his colleagues in the MFA program constituted a golden generation that included such future luminaries as Richard Serra and Brice Marden.

While writing Chuck Close: Work, I soon realized that I had been flattering myself in thinking that my knowledge of his art was reasonably comprehensive. I had previously written about several of its aspects, notably his paintings and dot drawings, but now I was hit by just how many facets there are to his work. Close might have one primary subject, the human face, but he brings to it an infinite variety of approaches. (I can imagine a story by Jorge Luis Borges in which an artist named Chuck Close fills a studio with endless portraits of the same sitter, each of them entirely different.)

Something similar happened when I began working on Chuck Close: Life. Here was someone who had been a friend for forty years, and whom I thought I knew pretty well, but the gaps in my knowledge of his past were enormous. These lacunae were filled during the course of the aforementioned long sessions of informal dialogue. We would sit in the artist’s studio or in some NoHo bistro for hours at a stretch, talking about anything and everything—old friends and current art world gossip, Yankee games and auction prices—pausing for an espresso or a drink then almost at random turning to matters directly related to the book. It was during these rambling conversations that—to paraphrase Chuck—the process really began to percolate, as we reached back to the roots of our friendship and became so relaxed that, when we did turn to matters connected with the narrative, rich nuggets would emerge. It was during conversations like this that he would suddenly recall the art epiphany he experienced at a Billy Graham rally in Tacoma, or an incident involving Robert Rauschenberg and a chicken in a New Haven lecture hall. This kind of enjoyably discursive dialogue, especially when exploring his early years, enabled me to piece his life together as if reassembling an ancient artifact from shards—or accumulating a narrative by means that have something in common with the incremental process used to produce a Chuck Close portrait. This process continued for three years, with some of the most critical material emerging during the final weeks before my deadline.

At the outset of his career, Chuck described his paintings as “mug shots,” preferring to think of them as “heads” rather than portraits in the traditional sense. Over the past four decades, he has moved away from that concept—at least in its most literal form—demonstrating that there are many valid ways to make a portrait if pursued with rigor and integrity. One rule he has adhered to from the beginning, however, is that he never sets out to flatter. In a recent interview, he talked about his regard for his sitters when considered in this light.

“It’s an act of tremendous generosity and bravery to submit to my photographs. … Anyone I’ve painted has [given me] an extraordinary gift by lending me their image, with no control over what I’m going to do with it.”

This book is the result of a huge act of generosity on the part of Chuck Close. He gave of himself magnanimously, as did many other people who unstintingly shared their recollections and reflections with me, enabling me to create this portrait of the artist. I hope I have done them justice.

Prologue

At five o’clock in the afternoon of December 7, 1988—the forty-seventh anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor—Chuck Close finds himself in Yorkville, the old German neighborhood on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. At the age of 48, Close has established himself as one of the most accomplished painters of his generation, already the subject of a major museum retrospective and a full-scale monograph. His most recent exhibition, at the Pace Gallery, was rapturously received by both critics and his peers.

Well over six feet tall, slim but broad-shouldered, with a full beard and thick glasses, Close is a familiar presence in art world haunts from the bistros of SoHo and Tribeca to the galleries of Fifty-seventh Street and Madison Avenue. Yorkville, however, is off the beaten path for him. He is here, and more conservatively dressed than usual, because he’s on his way to Gracie Mansion—the official residence of the mayor of New York—for the annual awards ceremony of the Alliance for the Arts, at which he is to be a presenter.

Close is feeling under the weather. For a couple of weeks now he’s been suffering from a miserable respiratory infection, accompanied by a hacking cough. On top of that he woke up this morning with severe chest pains, but was not especially worried by this because he has a history of angina-like episodes, none of which has ever progressed to anything worse, or led to a credible diagnosis of a heart condition. He puts them down to stress but likes to add, “Denial runs in my family.”

He’s a little early so he stops into a neighborhood tavern and orders a scotch, hoping the drink will make him feel better. Instead he feels worse. He’s nauseous and, by the time he leaves the bar to walk the last few blocks to Gracie Mansion, the chest pains have returned. It’s dark by now, and the day has turned cold. He walks past storefronts trimmed with Mylar icicles and blinking Christmas lights, past Chanukah candles glowing in apartment windows, arriving at Gracie Mansion a little before six. There he’s shown into a reception area where hors d’oeuvres are being served. He sees people he knows but, although normally gregarious, is in no mood for casual socialization. The chest pains have become worse and he is beginning to take them more seriously. On the program he has been handed, he’s listed as the third presenter. Even assuming everything goes smoothly, that’s almost an hour away. Close approaches the woman in charge of the event, explains the situation, and requests that he be moved to the head of the list. She tells him that’s impossible.

As waiters circulate with canapés, Agnes Gund—a prominent collector and a trustee of the Museum of Modern Art—approaches Close and tells him she is pleased to have run into him because she has been meaning for some time to ask him if he would accept a commission to paint her portrait. As a matter of principle, Close never accepts commissions. He paints friends and family, and then only when and whom he chooses to—one of the ways in which he distances himself from the traditional role of the portrait painter with its feudal baggage of artist and patron. Under normal circumstances, Close would point this out politely and with a palliative dose of charm, but in pain and with claustrophobia pressing in on him, his reaction to Gund’s request verges on rudeness. Surely she knows his policy on accepting commissions? It’s no secret, after all. His curtness, so out of character, takes the collector by surprise, and she backs off.

At 6:10, as scheduled, the mayor—Ed Koch—appears to introduce the awards ceremony. By now, the chest pains have become almost unbearable. As Koch begins his introductory speech, Close leaves his seat and once again confronts the woman in charge of scheduling. He makes it clear that the moment for protocol is past. He needs to get medical attention as soon as possible. If he is to present the award, he must be moved to the head of the list; otherwise he will leave immediately. This is a demand rather than a request and is finally agreed to. An offer is made to call an ambulance, which he refuses, but a police officer is alerted to accompany him to Doctors Hospital, which, fortuitously, is just across the street from Gracie Mansion. Even so, Close must wait through the mayor’s speech, and Koch famously relishes every minute in the spotlight, playing this evening to an audience of fewer than a hundred people with a born performer’s hunger for applause, his timing as measured as Jack Benny’s. At last he’s finished, and Close is introduced. He makes his way to the dais and reads the citation.

“Louis Spanier, visual arts coordinator, community school district thirty-two, is being honored for bringing an appreciation of the visual arts to students in the Bushwick area of Brooklyn …”

The pain and the constriction in Close’s chest are such that he has difficulty getting the words out. He makes the presentation, and then instead of returning to his seat, hurriedly and unsteadily leaves the room. Accompanied by the assigned police officer, he makes his way on foot the short distance to the Doctors Hospital emergency room, where—a miracle for New York City—not a single patient is waiting. Close is attended to immediately. He is given massive doses of painkillers, and intravenous Valium for sedation.

Fully conscious, Close requests that his wife, Leslie, be alerted. She hears the phone as she awaits the elevator outside the couple’s Central Park West apartment, on her way to the Pace Gallery Christmas party. She jumps into a cab and heads for the hospital, not as alarmed as she might be because she too has been through this before. Like her husband, she initially puts this latest episode down to the effects of stress and fatigue, but the scene that greets her at the emergency room quickly dissolves any vestige of complacency. The urgency communicated by the staff immediately brings home the seriousness of the situation, and to make things worse no one can tell her exactly what the problem is. They are testing for cardiac arrest but cannot confirm that that is the explanation. Only one thing is clear—the situation is critical.

There is a feeling of helplessness that comes in a moment of crisis like this—a sense of being in the way yet needing to be there, of wanting answers to questions that may be unanswerable.

Suddenly Close goes into convulsions. Long and frenzied, it seems they will never end, but then just as suddenly his body is still, unnaturally so, just lying there, dead weight, flesh without animation.

Still fully conscious, Chuck Close is paralyzed from his shoulders down.

Part I

Fig. 1:Four generations: the infant Chuck Close in the arms of his maternalgreat-grandfather, Benjamin Albro, with Chuck’s mother, Mildred Close, left,and Blanche Albro Wagner, his maternal grandmother, 1940.

Chapter 1

Born on the Fifth of July

It is unusual, to say the least, for a living artist’s face to be featured on billboards, but not long ago commuters from Long Island, and travelers en route into Manhattan from Kennedy and La Guardia airports, were greeted at the entrance to the Midtown Tunnel by a towering black-and-white likeness of Chuck Close dressed in a black leather jacket and a white tee-shirt adorned with a facsimile of one of his many portraits of the composer Philip Glass. Had it not been for his unsmiling expression, it might have seemed that he had been appointed the city’s official greeter, an adjunct to the Empire State and Chrysler buildings. Nor did it stop there—a companion billboard was the first thing you saw as you emerged from the IRT subway station at Sheridan Square and, 2,500 miles away in LA, another overlooked the Walk of Fame on Hollywood Boulevard, while a Godzilla-scaled photomural climbed the side of an office building on the Sunset Strip. Sponsored by the Gap to promote the Whitney Museum Biennial Exhibition, the image used at all these sites was also featured on the back cover of The New Yorker and prominently in other periodicals; but then it’s not unusual to find Chuck Close’s likeness on the pages of publications ranging from New York Magazine to Interview to W, and he has produced enough self-portraits—around one hundred so far, including paintings, prints, drawings, and photographs—to have merited a full-scale traveling retrospective that consisted of nothing else. To those who follow the American art scene, Chuck Close’s face is as familiar as any since Andy Warhol’s.

Faces are the artist’s business, and a biographer must contend with the fact that this subject has already accumulated and presented an extensive visual autobiography which commenced in 1967 when he conceived the iconic Big Self-Portrait now hanging in the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis—a painting nine feet tall, severely black-and-white like those recent billboards, a vision of the young artist as outsider, cigarette smoldering between lips parted into the hint of a sneer, the cumulative effect proto-punk and confrontational. That at least was the impact the painting had until, with the passage of time, reverence crept into the artist-viewer relationship, as it inevitably does, altering the experience as it alters that of reading a Kerouac novel half a century on or watching a nouvelle vague movie at some revival house. The experience is still powerful, but has undergone a sea change.

The image most associated with Close’s likeness today is that of the New York sophisticate, the insiders’ insider. He seems to know everyone and to be at every major opening, every A-list party, feted and showered with awards and honorary degrees. He was the first artist to be appointed a trustee of the Whitney Museum (and is one of very few to have had retrospective exhibitions at the Whitney, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Metropolitan Museum). He is active in the American Academy of Arts and Letters, a member of the New York City Cultural Affairs Advisory Commission, and sits on the boards of a number of organizations concerned with the well-being of education and the arts. He is, in fact, the consummate New York cultural establishment figure, to the extent that it has become difficult to understand just how shocking—transgressive even—paintings like Big Self-Portrait seemed when they were first shown. (The New York Times critic Hilton Kramer characterized Close’s debut exhibition as, “The kind of garbage washed up on shore after the tide of Pop Art went out.”)

Given his present eminence, and his current identification with New York, it may come as a surprise to some that Chuck Close was born a continent away from Manhattan. He did not, in fact, set foot in the Big Apple till a few weeks before his twenty-first birthday nor take up residence there till he was twenty-seven. That was when, in a downtown loft as bare of luxuries as any Trilby era Montmartre garret, he began Big Self-Portrait. From his student days, when he first encountered the work of Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock, making it in New York had been his goal, but—like Pollock, like Robert Rauschenberg, like Jasper Johns and so many other major American artists whose names have come to be associated with the Big Apple—Chuck was in fact a product of what would appear to be an unpromising provincial backwater, in his case the industrial fringes of Puget Sound.

Thus, there are almost three decades for a biographer to explore before the artist’s visual autobiography was definitively launched. Chuck Close is a self-made New Yorker, and a master of the New York School of painting, but beyond that he is an American artist, in the sense that Vermeer is Dutch, and Cézanne French—representative of an entire culture.

Chuck Close can point to forebears from Ireland, Denmark, Quebec, and elsewhere, but from the mid-nineteenth century on his family was the product of the rural Midwest, of farms, floods, droughts, and modest railroad towns where livestock was loaded for transport to stockyards in Omaha and Chicago. Like other families that had had enough of tornadoes, blizzards, and backbreaking dawn-to-dusk work harvesting sweet corn or sugar beets, the Closes, Wagners, and Albros who are Close’s antecedents migrated westward, finding their way to the Pacific Northwest and the burgeoning cities and towns clustered around Seattle.

Chuck was cheated by a few hours of having the archetypal birth date for an American artist. On Independence Day, 1940, in Monroe, Washington, a small mill town on the Snohomish-Skykomish river system, Mildred Emma Close, age 27, was full-term with a child who—uncharacteristically in light of later developments—seemed in no great hurry to make an entrance onto the world’s stage. The baby’s arrival had been predicted for the middle of the previous month, but the evening of the 4th arrived with no sign of an impending birth. As darkness fell, Mildred’s husband, Leslie Durward Close, set off a barrage of fireworks and firecrackers. According to family legend, this was the trigger. Early on the fifth, Mildred went into labor. A local physician—Dr. Cooley—was summoned, and in the bedroom of his parents’ tiny clapboard cottage at 134 South Madison Street—which had been scrubbed and sterilized daily for weeks in anticipation of his arrival—Charles Thomas was delivered, his weight at birth a healthy nine pounds.

Fig. 2:The house in which Chuck Close was born, 134 South Madison Street, Monroe, Washington

His father immediately phoned Mildred’s parents in Everett, fourteen miles downstream, and within a few hours her mother, Blanche Ethel Wagner—who had been frantic with worry because of the extended pregnancy and the thought of her daughter giving birth without her—arrived at the cottage in a black Ford sedan driven by her sister, Bina Almyra Albro. (Much of the information in this chapter derives from a detailed typewritten account of Chuck Close’s antecedents prepared at his request, in the early 1980s, by his Great Aunt Bina Albro.) Many years later, Bina reported that she would never forget her first impression of Charles Thomas, “still red and such a big lump of a baby that no one would mistake for a girl …”

This last observation was prompted by the fact that, in anticipation of the imminent arrival, both Mildred and Blanche had spent a multitude of hours sewing and embroidering baby clothes. It seems, however, that they had been expecting—perhaps even hoping for—a girl since Bina would recall that many of these garments were hardly appropriate for a boy. She remembered in particular the spectacular, long christening gown, trimmed with yards of lace. Despite protests from his father that this garment (though in fact traditional) was highly inappropriate for a boy, the baby wore it for his October 6 christening, at Monroe First Methodist Church, through which he slept soundly. Afterward there was time for a single snapshot before his father insisted that the infant be changed into something deemed more appropriately masculine.

Bina was asked to become the baby’s godmother. Her contribution to the layette was a white reed basinet, hooded and lined with shirred Japanese silk and furnished with a matching lace-edged coverlet. The shirring had been done by women at the factory where Bina kept the books, a business devoted to the manufacture of funeral caskets.

Both of Chuck’s parents were migrants to the Pacific Northwest from the American heartland. An only child, his mother, Mildred Emma Wagner, was born in October 1913, to Blanche Wagner, at the Birdwood ranch a dozen miles northwest of North Platte, Nebraska.

Birdwood was the home of Blanche’s parents, Benjamin and Emma Albro. Aunt Bina—born in a sod homestead in 1902—lived there at the time of Mildred’s birth, as did Theodore—“Teddy”—Bina’s younger brother, born in 1910 when his mother was forty-two years old. Emma had believed herself to be past menopause and did not realize she was pregnant until a week or two before giving premature birth to a baby weighing less than two pounds. Incubators were such a novelty in those days they were a popular feature of the midways at spectaculars such as the St. Louis Louisiana Purchase Exposition, and even entertained gawkers at Coney Island’s Luna Park. The Albro clan had no access to one so they made do with a washbowl full of olive oil placed on the hot water reservoir of the kitchen range to keep it warm. When Teddy turned blue he would be immersed in the oil, except for his face, and gently massaged until his color improved. Then he would be taken out and wrapped in flannel. Uncle Teddy not only survived but grew up to be a strapping adult, six foot two inches tall.

Fig. 3:Close’s maternal grandparents, Charles and Blanche Wagner, with Mildred Emma Wagner, Chuck’s mother, c. 1915

Millie’s father, Charles Henry Wagner—whose own father had been born in Denmark—originally came to Birdwood to help on the ranch, Blanche having fallen in love with him while teaching in a one-room schoolhouse in northern Nebraska. As described by Bina, Birdwood sounds idyllic—a setting waiting to be painted by a Regionalist artist such as John Steuart Curry, the big house located among a grove of trees near a lake created by the damming of a creek. In fact, though, life was far from arcadian. The children were expected to help with chores—from milking, to mucking out the horse stalls, to cooking for seasonal migrant workers housed in the haylofts—though Benjamin never forced them to do jobs unsuited to their age and physical limitations. The brutal Nebraska climate made for a life that was harsh and sometimes cruel, and however hard they worked, the Albro/Wagner clan did not enjoy much security because they were tenant farmers, owning little beyond their animals, farm equipment, and household belongings. Not long after Millie was born, Birdwood was sold from under them.

Fig. 4:Mildred Close’s graduation photo,Auburn High School, c. 1930

There were subsequent attempts to scrape a living from the land, and Benjamin’s prize mules continued to win ribbons at county fairs, but disaster was never far away. Bina would remember her father standing out on the porch of one farmhouse, watching as a hailstorm destroyed the entire corn crop.

When Millie was five, Charlie and Blanche Wagner found their way to Ravenna, a small city on the trunk line of the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad. The Burlington provided Charlie with work as a brakeman. Millie, meanwhile, was able to start school in a setting rather more sophisticated than the one-room schoolhouses that older family members had had to make do with, and also began to take piano lessons, quickly displaying a gift for the instrument. In 1918, Bina Albro moved in with the Wagners, and the following year, Benjamin and Emma finally joined the others in Ravenna, where Emma would die two years later.

Among the perks of Charlie’s job on the Burlington were free railroad passes. Not long after Emma’s death—in the summer of 1922 or 1923—the three Wagners took a trip west to visit Blanche’s sister Mabel, who had moved to Washington State. Charlie and Blanche fell in love with the Pacific Northwest.

“Who wouldn’t,” Bina wrote, “after living in Nebraska?”

Fig. 5:Mildred Close in recital dress, late 1930s

It did not take long for the Wagners to decide on a permanent move, with Bina accompanying them while her father and Teddy remained in Ravenna for one more year until Teddy completed middle school. In the late spring or early summer of 1924, with minimal belongings strapped to Bina’s old Model T tourer—spare tires and rolled bedding bulging from the driver’s side, a trunk clamped firmly to a rack suspended from the back of the car, pots and pans dangling—the quartet set out westward along dusty prairie and mountain roads, many of them unpaved, sleeping in tents at primitive auto-camps, making meals in the communal cookhouse or over an open fire. It was an odyssey undertaken by tens of thousands of Americans in the twenties and thirties, a journey that acquired mythic status in the pages of John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath.

After many flat tires and patched inner tubes, Bina, Blanche, Charlie and Millie made it to their destination, bones aching from potholes and cramped quarters but without having encountered any major crises. Jobs were not easy to come by, but eventually Charlie found work at the Fleischmann’s yeast plant in Sumner, not far from Seattle, and the Wagners plus Bina settled nearby in Auburn, then a small community of truck farmers, where Bina was hired by the casket manufacturing factory.

Benjamin and Teddy finally joined them in the Northwest, driven out there by another of Benjamin’s sons, Floyd, in what Bina describes as “a makeshift camper” constructed on the body of a small roadster that had been retrofitted with an improvised flatbed at the rear and a prairie schooner–style canvas canopy. The reason for this jerry-built rig was that Benjamin had broken his leg and was forced to travel on his back on a mattress strapped to the flatbed. Bina was able to find her father a job with the casket company, and soon she was able to buy a home for her parents in the city of Everett, north of Seattle.

The Wagners remained in Auburn, some fifty miles away, but stayed in close contact. The latter part of the 1920s was a reasonably settled and prosperous time for the Wagners with Millie adapting readily to her new surroundings. She was a strong, healthy child, Bina would remember, and strong-willed too. She seems to have done well in school and to have displayed considerable gifts as a pianist, studying with the top teachers in the Seattle area. Undoubtedly she dreamed of having a career as a concert pianist, but any such ambitions had to be put aside because of the onset of the Great Depression, which plunged the Wagners into dire financial circumstances once again. Losing their house in Auburn, they eventually moved in with the Albros in Everett, where Bina was able to use her influence to find Charlie an opening at the casket factory as well. She reported, however, that the long months out of work, and the stress of losing his home, had taken its toll, writing that, “having to start over again just seemed to change him.”

A teenager at the time, Millie must have felt her father’s pain; his chronically high strung and phobic wife certainly did. “As she grew older,” Bina writes, “[Blanche’s] nervousness and fears increased.” She became very possessive towards her daughter, which may have put a further damper on Millie’s musical ambitions since her mother had a horror of her loved ones moving away from home. Millie, however, was a tough-minded young woman, determined to avoid developing any of her mother’s fears. Chuck describes his mother as being “counter-phobic”—someone who consciously neutralized any tendency towards phobia by becoming a risk-taker. She would prove less successful in eliminating from her own makeup Blanche’s possessive instincts.

Shortly before she graduated from high school, while the Wagners were still hanging on in Auburn, Millie met Leslie Durward Close during choir practice at the local church. A recent arrival in town, and ten years older than Millie, Les was a personable young man who, according to Bina, “dressed quite well.” He made a good impression on Millie’s parents, and soon Les and Charlie joined forces to hunt for jobs, agreeing that they would never sign on with the WPA or any such federally sponsored relief agency, disdaining government handouts—always referred to as “the dole”—as beneath the dignity of honest working men. (Later, Les—who was in fact sympathetic to the Roosevelt administration—did take a WPA job, helping to create an entirely unnecessary island in the middle of a lake.)

After graduation, Millie moved to Everett to live with Bina and her grandfather on the theory that she would have a better chance to acquire paying piano students there. Les remained in Auburn and took Millie’s place in the Wagner household, renting her former room. Before long the Wagners made the move to Everett, and Les came too, managing to earn a meager living performing various freelance jobs. He developed a considerable reputation as a “douser,” or water diviner, using forked twigs to determine the spot where a well should be sunk. (Chuck, who later went along on such expeditions with his father, recalls that he never failed to find water.) More profitably, Les established a name for himself as a window dresser, arranging displays for stores in downtown Everett as well as in nearby smaller towns. He must have shown imagination and flair since at the height of the Depression no retailer was likely to hire an outside window dresser unless the results generated cash flow.

One of Les’s major commissions during this period was to completely revamp the vitrines of the Lloyd Hardware Company, a big, bustling store at the major intersection of Hewitt and Broadway in downtown Everett. Lloyd’s had many windows, which Les fitted with shelves, steps, and platforms that permitted the installation of livelier, multilayered displays. This led to him being hired as a clerk in the store at $15 a week. He continued to do displays for other stores in his free time, and by 1934, three years after they first met, Les and Millie decided that, between his earnings and her piano lesson fees, they were doing well enough to get married. As much as the family liked him—in truth, he was already practically a member—the idea met strong resistance, with everyone urging the couple to wait for better times. When it became evident that their minds were made up, plans were put into motion for a July 3 wedding, which took place in Millie’s parents’ house. Blanche made Millie a white satin wedding dress that Bina describes as “lovely.” Because the house was tiny, and perhaps because times were hard, the guest list was restricted to a few friends and family members.

The Wagner/Albro concerns about the prudence of the marriage proved unfounded, and the couple got by modestly but comfortably in Everett until a more desirable opportunity prompted them to pull up stakes once more. One of Les’s freelance window-dressing jobs was with another large hardware store, this one upriver in Monroe. Les was offered a full-time position there, a better-paying proposition that called for him to do sheet metal work, lay linoleum, install countertops, and the like.

It was thus that Les and Millie Close were living in Monroe when Millie became pregnant.

Fig. 6:Leslie Durward Close,Chuck’s father, foreground,with mother Lulu May Reno Close,half-brother Orville Guilander,and father Thomas B. Close,c. 1907

By comparison with the saga of the Wagner/Albro clan, scant information has survived about Leslie Durward Close’s background. What can be said with confidence is that his grandfather was George Close, who, in the 1840 census, was listed as living in Kane, Illinois, a small town in agricultural Greene County in the western part of the state. Leslie’s father, Thomas B. Close, was born there in 1869, and married Lulu May Reno, who had previously been married to Jesse Guilander and by whom she had a son, Orville—Leslie’s half-brother, seven years his senior—who spent his entire life farming in western Illinois. Les himself was born in Kirkwood, Missouri, a residential satellite of St. Louis, but was brought up on the family ranch, where as a very young man—while in the fields harvesting grain—he suffered a ruptured appendix. The weather was stifling hot and the nearest hospital miles away. By the time he saw a doctor, he had developed peritonitis—inflammation of the tissue that lines the walls of the abdomen. Surgery was performed that resulted in the formation of adhesions—bands of scar tissue that can cause intestinal blockages. From that point on, Leslie Close’s health was compromised. He was unable to continue with the chores generally assigned to a farmer’s son and instead learned to help his mother in the kitchen, cooking for the family and the ranch hands. Further medical problems, including a heart condition, would pursue him to the Pacific Northwest when he moved there in his late twenties.

Fig. 7:Young Leslie Close standing behind his father, Thomas Close, left,and half-brother, Orville Guilander, Kane, Illinois, c. 1915

After that move, his ties to his family back in the Midwest seem to have become tenuous. The unstinted enthusiasm, and perhaps gratitude, with which Les embraced the Wagners and the Albros suggests that they provided him with something he might have been missing, a secure family environment in which he felt he belonged. The warmth the Wagners and Albros exhibited towards him was itself an expression of something that seems to have sprung from rural America at its best. Les was not exactly the man from nowhere, torn from the pages of a James M. Cain novel, but he had arrived in their life without references, forming a romantic attachment to the Wagners’ considerably younger teenage daughter; the family had accepted that and trusted his intentions.

(In some respects, the situation resembled the one that Chuck Close would find himself in when he grew up and took a bride.)

It would emerge many years later that there was a secret in Leslie Durward Close’s past. He did not hide it from Millie, and it was known to her parents and to Bina, but it was strenuously concealed from his son for more than forty years.

Fig. 8:Chuck Close dressed as a magician, c. 1947

Chapter 2

Learning to be Unafraid

In the aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Close family’s life was upended once again. Leslie had been a member of the Coast Guard Reserve, but his poor health prevented him from playing an active role in the war. Soon after the outbreak of hostilities, however, he was taken on as a civilian employee of the military at Paine Field in Everett. Built as a WPA project, Paine Field had been appropriated by the Army Air Corps at the outbreak of war, the squadrons based there being charged with defending the nearby Bremerton shipyards as well as the Boeing plant and airfield in Seattle. Leslie Close was hired as foreman of the sheet metal shop, a job well suited to his blend of practical and imaginative talents.

The bread-and-butter part of the job involved carrying out work for the buildings that were being erected to accommodate the Air Corps personnel and equipment, but the job also provided the opportunity for him to exercise his imagination, solving problems that arose under extraordinary wartime circumstances. A number of these solutions resulting over the next several years in patented inventions ranging from a large-scale filter laundry system that could handle mess shirts, service issue underwear, and fatigue jackets in unprecedented quantity, to a “roof jack”—a form of flue that made heating Quonset huts more efficient—to a luminous paint that when applied to the tarmac made night landings possible without the need of runway lights. These inventions did not make him rich, though the military presented him with a check for $100 for his contribution in designing and building the filter laundry system, said at the time to have saved Paine Field $4,000, and the improved roof jack, which saved the government millions when installed around the world, earned him a letter of commendation from the Secretary of Defense. To make ends meet, Les still dressed windows and accepted dousing jobs in his spare time.

The fact that Leslie was now employed at Paine Field meant that the Closes were living near Millie’s parents once again—next door in fact—so that from the age of eighteen months Chuck basked in the adoration lavished on him by Charlie and Blanche, and in her more restrained way by Bina, too.

Fig. 9:Mildred, Leslie, and Chuck Close in his grandparents’ yard, summer 1941

Chuck’s early childhood seems to have been largely unclouded. There might be a war on, and money tight, but he was in a manifestly loving environment, and never lacked for anything. Despite wartime shortages he always had playthings since his father—a classic bricoleur—was able to renovate old toys or to create new ones from scratch, including a rather modernistic looking bicycle. In fact, Chuck—initially known in the family as Charlie, like his grandfather—was always more than adequately supplied, as is recorded in the birthday and Christmas gift lists in a baby album—All About Our Baby—meticulously kept up by his mother, not just for his first year but for seven. Early gifts included rubber Mickey Mouse figures, toy soldiers, a xylophone, a “magic slate,” modeling clay, a red wagon, and for his third birthday, a Jeep (though Millie would insist that the boy’s favorite toys were the bottles, containers, and cooking utensils he found in her kitchen). Later birthdays brought a racing car, a baseball bat, a soldier’s costume, a wristwatch, a toy telephone, and a toy typewriter, these items inevitably supplemented with more practical gifts such as shirts, shoes, pajamas, pillow cases, and soap.

One Christmas, Chuck received so many presents that they filled a laundry basket to overflowing.

Fig. 10:Leslie Durward Close, May 1945, in a photo taken for a patent application for a filter laundering system

Chuck belonged to a generation whose parents had survived the Depression and were determined that their children should have the advantages they had lacked. If anything, he was the object of excessive attention. His grandmother was possessive and perhaps prone to smothering. While Millie probably did her best not to emulate her mother in this regard, she was tightly focused on her son’s progress in the world, wanting and in fact demanding the best for him. That focus is amply illustrated by the baby album, which is scrupulous in its attention to detail, with Millie always referring to herself in the third person as “Mother.”

Spent 4th birthday in California, very lonesome for Daddy. Mother bought him some tinker toys, paints and paint books and kaleidoscope.

Certainly this was a prophetic choice of gifts for someone who would later make paintings that have a decidedly kaleidoscopic aspect. Elsewhere in the album, important developments are duly noted. We learn, for example, that Chuck took his first steps on May 11—Mother’s Day—when he was ten months old. We are told that on his first visit to the dentist he was “a good boy.” He is in fact so frequently referred to as a good boy that it’s a relief to discover that his first spoken sentence was “I don’t want to.”

Bina’s manuscript describes Millie as, “a hardworking person, intelligent and very efficient. … I’m sure many of her friends thought she had a college education. … I’m sure she was not ashamed of [her background,] but I do know that it takes an extra effort to overcome the effect of spending your ‘learning’ years with a family that had not had the advantage of a decent education. She succeeded …mainly because she had the self-assurance to use the knowledge she gained through her study and reading.”

Fig. 11:Chuck with his mother, c. 1943

Bina touched on some of Millie’s faults, too, saying, “She was not always easy to live with. She was inclined to dominate and take charge—often because she did know more than some about a subject or could do some job more quickly.” Offsetting this, Bina detailed many instances of Millie’s devotion to her family, always making herself available to look after sick relatives, or to pitch in whenever there was a problem of any sort to be dealt with. Bina reported too on the physical ailments that must have had an impact on Millie’s personality. These included severe migraine headaches—something she had in common with her father—and like her mother, she was subject to heavy and painful menstrual periods, sometimes hemorrhaging, which led eventually to a hysterectomy. Bina describes her as “having the ability to tolerate a great deal of pain and also a great determination to survive.”

In 1946 Paine Field reverted to civilian control, but Leslie Close was given the opportunity to continue his civil service career at McChord Field, a U.S. Air Force base in Tacoma. This entailed another move, a ninety-minute drive from Everett along Route 99, with the family first renting in one of the sprawling government projects that had sprung up near the base, and later relocating to 3317 South Monroe, a modest tract home in a section known as Oakland where their neighbors were predominantly working- and lower-middle-class families, many dependent on paychecks from either the Pacific Match Company or Nalley’s Fine Foods, the big local employers.

Fig. 12:Chuck stands outside of his grandparents’ home on Cady Road, mid-1940s, on a bicycle made by his father

(When very young, Chuck ran away from home, inspired by a billboard that announced “You Are Entering Nalley Valley,” this being the name given by the locals to the area where the company was headquartered. Once there, he expected to find himself in the arcadian world portrayed on the billboard—a cartoon paradise populated by Disneyesque bunnies, squirrels, bluebirds, and adorable baby deer—and anticipated feasting on the potato chips that had made the Nalley name familiar throughout the Northwest. He was disappointed to find only food processing plants and warehouses.)

By now Chuck had begun school, and it was here that he would first face the difficulties that would dog him for years but that ultimately may have contributed to his success as an artist and to his ability to cope with an encounter with near tragedy.

Early report cards, however, shed little light on these latent problems. He began kindergarten in September of 1945, before leaving Everett, but that report card, signed by his first teacher, Evelyn Shockby, concerns itself primarily with attendance and categories of behavior such as habits regarding health (“Showing by his alertness that he has had sufficient sleep”), citizenship (“Showing care of his own belongings”), and of gaining new experiences and conveying old ones (“Expressing his ideas through playing in sand, building, drawing, painting, and modeling”). Interestingly, this last sub-category is one of only three out of twenty in which he failed to attain a perfect score. (His worst was for “Using a handkerchief when needed.”) Additionally, the teacher noted that he had “a marked ability to depend on himself.”

Fig. 13:Christmas, c. 1946

When he progressed to first grade in Tacoma, his teacher Fern Schachterle commended “Charlie” for his effort and for his ability to express his thoughts. In the second quarter he was praised for his improvement in reading, which has some relevance given that it would soon become apparent that—although the terms weren’t in use at the time—Chuck suffered from chronic dyslexia and from a perceptual disability called prosopagnosia. It would be in the higher grades that dyslexia would shadow his life more definitively, but it manifested itself from the outset. He remembers having difficulty learning to read and problems with mathematics—even with adding and subtracting—and from the time he first learned to write, he would sometimes produce mirror writing, now seen as characteristic of many dyslexics. (Leonardo da Vinci, retrospectively diagnosed with the disorder, is famous for having employed mirror writing in his notebooks.) Chuck also displayed the ability to write upside down as fluently as he wrote normally.

Prosopagnosia is a condition that makes it difficult to recognize faces. In extreme cases, it can mean that the victim does not recognize members of his own family and, in very rare instances, cannot recognize his own face in a mirror. Chuck does not suffer from the condition to anything like that degree, but the move to Tacoma, which involved meeting new people, alerted him to its existence. He was outgoing and made friends easily, but he found that, when re-encountering a recent acquaintance in the playground at Oakland Elementary School, often he would be unable to identify him or her even though the face might seem vaguely familiar. Adding to the problem, he had difficulty remembering names. Embarrassing situations were inevitable, and he quickly learned to compensate, using non-facial characteristics—a hairstyle, a way of dressing, an individualistic gait—as aids to identifying people. (Typically, a victim of prosopagnosia has no difficulty recognizing things other than the topography of individual faces.)

To have difficulty placing faces is an interesting condition for a future painter of portraits to be afflicted with. Chuck discovered early on, however, that usually he could “learn” a face more easily if he could see it represented in two dimensions, as in a snapshot, for example. Even this was not foolproof, but it certainly inclined him towards an interest in planar representations.

An ability to reduce topography to two dimensions proved to be a solution to one function of his dyslexia. When traveling through an unfamiliar neighborhood, searching for a specific destination, dyslexics are apt to turn left when they should turn right. The projects where the Closes lived when they arrived in Tacoma were laid out on serpentine streets that looped back on one another—potentially very confusing—but Chuck found he could find his way anywhere by picturing the layout of the streets as if represented in the form of a map or an aerial photograph. (Today, he claims that he can draw a plan of every room he has ever been in.)

ENDE DER LESEPROBE